Language is more than a means of communication; it is a vessel that carries memory, identity, and the inherited stories of a people. In the Ancient Near East, where literacy was limited to scribal classes and oral tradition dominated communal life, the shape of a word could preserve the shape of a worldview. Israel’s language—Early Northwest Semitic gradually taking the recognizable form of Biblical Hebrew—bears within it the deep sediments of older civilizations.

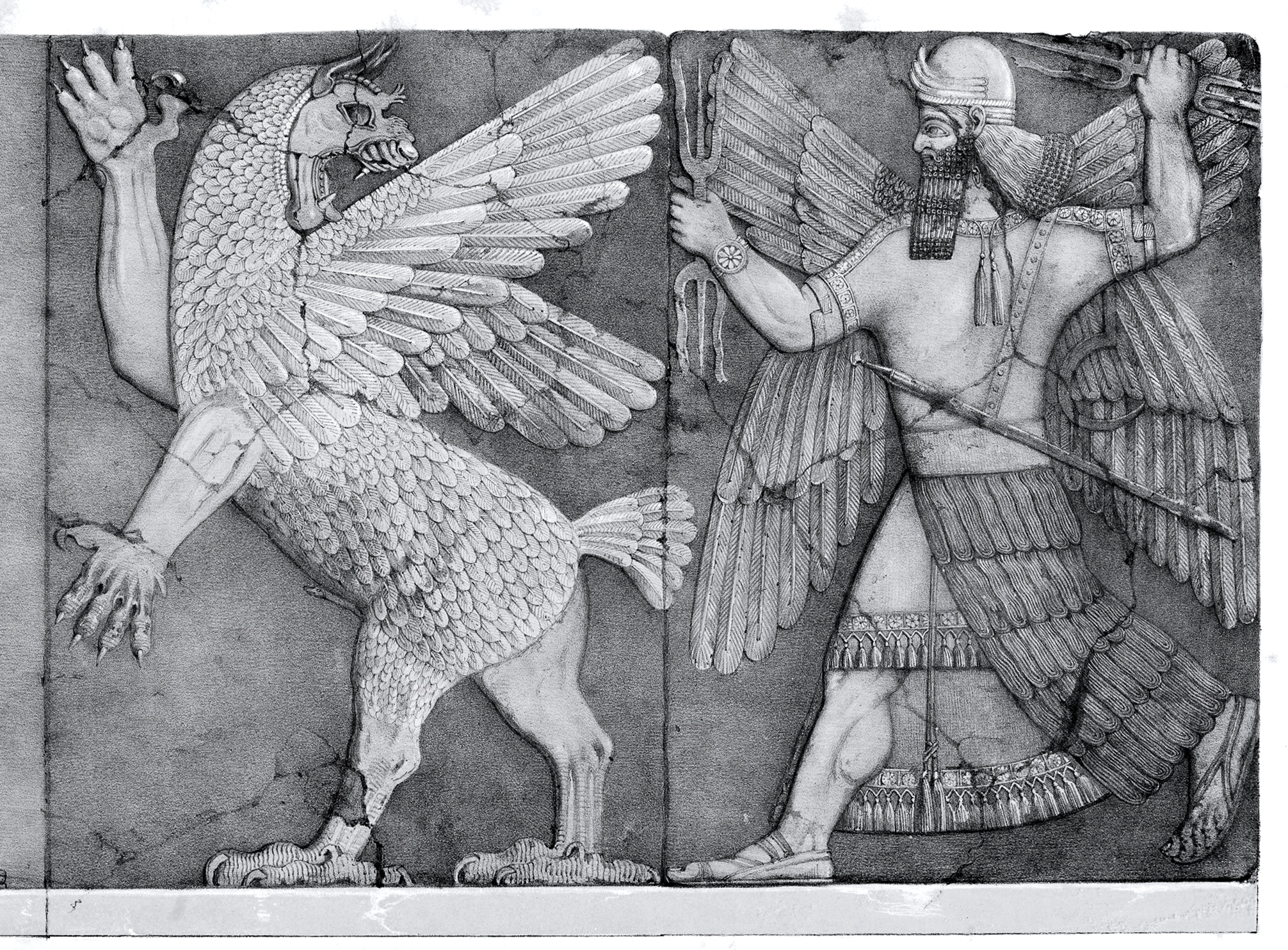

Hebrew did not emerge in isolation. It grew out of linguistic strata that link it to Akkadian, Ugaritic, Amorite, Phoenician, Aramaic, and other West Semitic dialects. Many of these linguistic connections carry with them theological resonances. For example, the Hebrew word tehom (“the deep”) echoes the older Tiamat, the Mesopotamian goddess of primordial chaos. Although the biblical authors radically reinterpreted this term—stripping it of its divinity and reshaping it into an impersonal deep—the linguistic memory preserves a window into a shared mythic past.

Likewise, the word eden resembles the Akkadian edin, meaning “plain” or “steppe,” which appears in Mesopotamian texts long before Genesis. The divine epithet El Shaddai may carry Amorite origins, suggesting ancestral forms of worship predating the emergence of Israel. Even the word Torah has analogues in earlier Akkadian terms for instruction and decree, highlighting the continuity of legal and wisdom traditions across regions.

These inherited words did not dictate Israel’s theology, but they shaped its imaginative possibilities. When biblical authors told creation stories, they used vocabulary already weighted with older meanings—sometimes affirming them, sometimes contesting them, often transforming them. Language thus functioned as an archive of myth, a repository of cultural memory from which Israel crafted its own distinctive religious vision.

Through linguistic inheritance, Israel participated in a millennia-long conversation. The result is a Bible whose words are both deeply local—rooted in the speech of hill-country villagers—and cosmopolitan—shaped by the vast intellectual world of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and beyond. Language preserved continuity even as theology evolved.

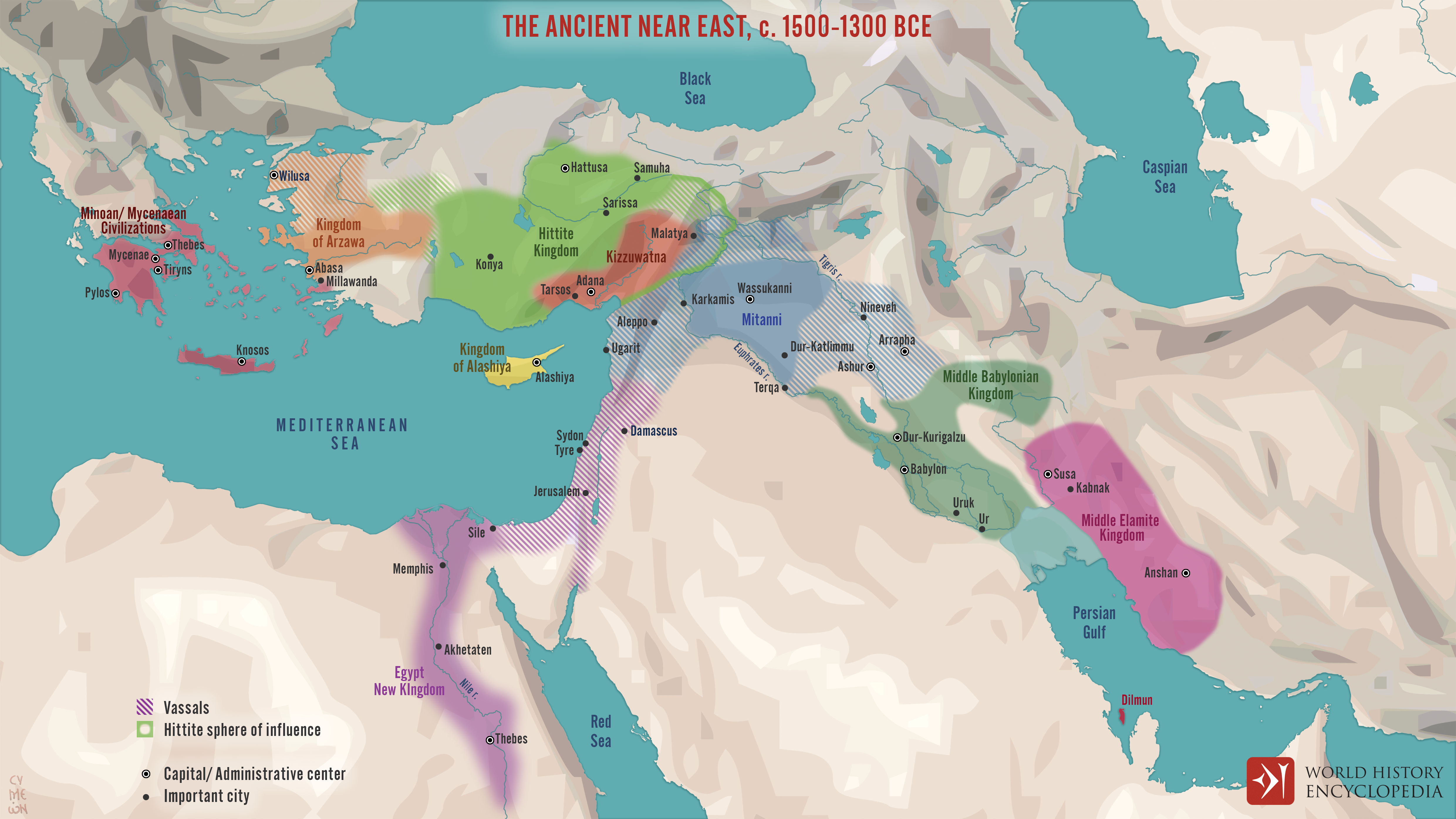

Syncretism was not unique to Israel or Canaan; it was the default mode of religious life throughout the Mediterranean and Near Eastern world. Seeing how other cultures blended their gods and ideas helps illuminate the broader patterns within which Israel’s story unfolds.

In Egypt, for example, the rise of Amun-Ra—a fusion of Thebes’ local god Amun with the solar deity Ra—illustrates how political unification could produce religious unification. In Greece, Zeus-Ammon emerged when Greek mercenaries encountered the Libyan oracle of Amun, recognizing a familiar divine pattern in a foreign setting. In Asia Minor, the Hittites and later Luwians incorporated Mesopotamian storm gods into their own pantheons, creating composite deities whose identities spanned linguistic and cultural boundaries.

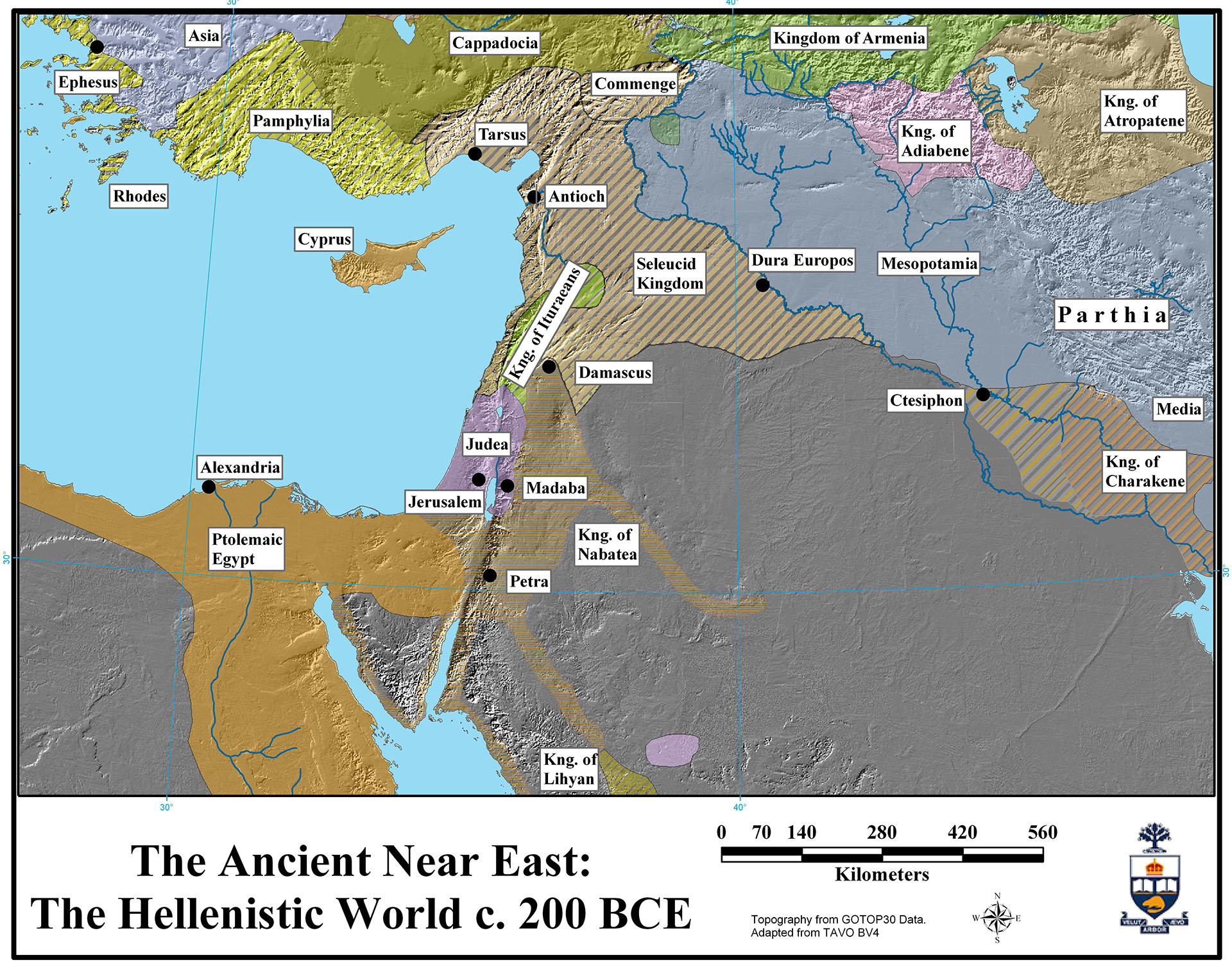

The Greco-Egyptian city of Alexandria provides some of the most dramatic examples of syncretism. The god Serapis was deliberately crafted during the Ptolemaic period to unify Greek and Egyptian religious sensibilities. Serapis combined aspects of Osiris, Apis, and Greek healing traditions into a single deity whose iconography intentionally blended cultural forms.

Such examples illustrate that syncretism served multiple purposes: political integration, cultural diplomacy, theological enrichment, and social cohesion. To the ancient mind, the divine was not a set of mutually exclusive propositions but a multitude of complementary manifestations of sacred power.

Israel’s resistance to syncretism must therefore be seen as an exception, not the rule. Most cultures embraced syncretism as a natural expression of the interconnectedness of the world. Israel, in contrast, eventually forged a religious identity through the renunciation of this universal cultural logic—a dramatic and unprecedented move.

By placing Israel within this comparative frame, we come to appreciate the radical nature of its later monotheistic commitments. Israel’s theological trajectory did not follow the dominant pattern of the ANE; it forged a new path, one that would profoundly influence the religious history of the world.

Israel’s eventual rejection of syncretism cannot be understood apart from the pressures of political vulnerability, imperial domination, and existential crisis. What had been religiously normal in earlier centuries became untenable as Israel sought to preserve its identity under foreign rule.

The Assyrian destruction of the northern kingdom in 722 BCE, followed by the Babylonian conquest in 586 BCE, shattered the old frameworks of community life. These catastrophic events forced Israel to confront a fundamental question: What does it mean to be the people of God when the land is lost, the temple destroyed, and the monarchy extinguished?

The prophetic literature answers this question by re-centering identity on exclusive loyalty to Yahweh. Syncretism, once tolerated or even celebrated, now represented a threat to Israel’s very existence. The prophets interpreted Israel’s political disasters as consequences of religious infidelity: worship of Baal, veneration of Asherah, and participation in Canaanite rituals were seen as betrayals of the covenant.

The Deuteronomistic historians crafted a sweeping theological narrative in which national survival depended on absolute devotion to Yahweh alone. The exile crystallized this vision. With the temple gone, Israel turned to Scripture, prayer, and communal practices of remembrance. Identity was no longer tied to land or cultic practice but to text, tradition, and monotheistic allegiance.

This reformulation of identity marks one of the most dramatic transformations in ancient religious history. Israel became a people defined not by the gods it shared with its neighbors but by the God it refused to share. This commitment to exclusivity—unique among the religions of the ANE—would shape the future of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In this transition, Israel moved from participation in a shared cultural grammar to the creation of an entirely new theological world—a world in which religious identity was defined by covenantal fidelity, ethical monotheism, and historical memory.

IX. Process-Theological Coda: Religious Evolution as Creative Transformation

From a process-theological perspective, the story traced in this supplementary essay is not merely a historical sequence but a pattern of creative advance. Cultures evolve as they encounter novelty, and novelty is taken up, integrated, or transformed according to the needs and possibilities of the moment.

Israel’s religion emerges as a prime example of such creative evolution. It begins with inherited materials—myths, linguistic structures, divine archetypes—and reshapes them through lived experience, ethical reflection, and communal struggle. The movement from polytheism to henotheism to monotheism is not simply a doctrinal progression but a profound increase in relational depth, moral vision, and conceptual coherence.

Process thought sees this not as a move away from the sacred diversity of the ancient world but as a new synthesis, in which the divine becomes understood as the One who holds relational multiplicity within a coherent unity. Increment by increment, Israel shaped and was shaped by its historical context, creatively transforming inherited religious forms into a singular vision of divine presence that continues to influence the world’s great monotheistic traditions.

In this reading, Israel’s journey mirrors the journey of human consciousness itself: moving from childhood images of the sacred, through adolescent conflict and experimentation, toward a more mature and integrated understanding of divine reality. The God of the Bible, seen through a process lens, evolves with the people—growing in conceptual richness, ethical force, and relational intimacy.

Epic of Gilgamesh, trans. Andrew George

Enuma Elish (Babylonian Creation Epic)

Ugaritic Texts, trans. Simon Parker

Hebrew Bible, NRSV or JPS Tanakh

Ancient Near Eastern Religion & Myth

Mark Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel

Mark Smith, The Origins of Biblical Monotheism

John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan

Thorkild Jacobsen, Treasures of Darkness

Tikva Frymer-Kensky, In the Wake of the Goddesses

Language, Culture, and Literature

K. Lawson Younger et al., A History of Ancient Near Eastern Literature

Edward Greenstein, Essays on Hebrew Poetics

Jo Ann Hackett, “Phoenician and Hebrew in the Iron Age”

Israelite Religion & Historical Context

William Dever, Did God Have a Wife?

Israel Finkelstein & Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed

Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament

Jon Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil

Process-Theological Context

Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality

Catherine Keller, Face of the Deep

John B. Cobb Jr., A Christian Natural Theology

Marjorie Suchocki, God, Christ, Church