In classical physics, two bombs with identical fuses would explode at the same time. In quantum physics, two absolutely identical radioactive atoms can and generally will explode at very different times. Two identical atoms of uranium-238 will, on average, undergo radioactive decay separated by billions of years, despite the fact that they are identical.

1. Particles and fields possess well defined dynamic variables at all times. Dynamic variables are the quantities used to describe the motion of objects, such as position, velocity, momentum, and energy. Classical physics presupposes that the dynamic variables of a system are well defined and can be measured to perfect precision. For example, at any given point in time, a classical particle exists at a single point in space and travels with a single velocity. Even if the exact values of the variables are uncertain, we assume that they exist and only take one specific value.2. Particles as point-like objects following predictable trajectories. In classical mechanics, a particle is treated as a dimensionless point. This point travels from A to B by tracing out a continuous path through the intermediate space. A billiard ball traces out a straight line as it rolls across the table, a satellite in orbit traces out an ellipse, and so on. The idea of a definite trajectory presupposes well defined dynamic variables, and so once the first point above is abandoned, the idea of a definite trajectory must be discarded as well.3. Dynamic variables as continuous real numbers. In classical physics, dynamic variables are smoothly varying continuous values. Quantum physics takes its name from the observation that certain quantities, most notably energy and angular momentum, are restricted to certain discrete or 'quantized' values under special circumstances. The in-between values are forbidden.4. Particles and waves as separate phenomena. Classical physics has one framework for particles and a different framework for waves and fields. This matches the intuitive notion that a billiard ball and a water wave move from A to B in completely different fashions. In quantum physics however, these two phenomena are synthesized and treated under a unified, magnificent framework. All physical entities are particle/wave hybrids.5. Newton's Second Law. Without the four kinematic features mentioned above, ∑F=ma∑F=ma is more than wrong, it's nonsensical. A radically different dynamics must be developed that is governed by a very different equation of motion.6. Predictability of measurement outcomes. In classical physics, the outcomes of measurements can be predicted perfectly, assuming full knowledge of the system beforehand. In quantum mechanics, even if you have full knowledge of a system, the outcomes of certain measurements will be impossible to predict. With the above list in mind, its no wonder that quantum mechanics took an international collaboration several decades to develop. How do you build a coherent model of the universe without these features?

1. Particles possess a wave function Ψ(x,t)Ψ(x,t) at all times. The wave function assigns a complex number to each point in space at each moment in time. This function contains within it all available information about the particle. Everything that can be known about the particle's motion is extracted from Ψ(x,t)Ψ(x,t). To recover dynamic information, we use Born's rule and calculate ΨΨ∗ΨΨ∗ to get the probability density of the particle's position, and we calculate ϕϕ∗ϕϕ∗ to get the probability density of the particle's momentum, where ϕ(p,t)ϕ(p,t) is the Fourier transform of the wave function. This is a radically different approach to kinematics than in classical mechanics, which describes particles by listing off the values of the dynamic variables.2. Trajectories are replaced with wave function evolution. As the wave function changes in time, so do the probabilities of observing particular positions and momenta for the particle. The evolution equation is the time-dependent Schrodinger equation:iℏΨ˙(x,t)=HΨ(x,t)iℏΨ˙(x,t)=HΨ(x,t). HH is the Hamiltonian operator for the system, i.e. the self-adjoint operator corresponding to the total energy of the system (described in point 3 below).3. Dynamic variables are Hermitian matrices. Instead of real-valued, continuously evolving dynamic variables, Schrodinger uses fixed Hermitian matrices (or self-adjoint operators) to represent observable quantities. Each observable such as position, momentum, energy, etc has a corresponding matrix/operator. The eigenvalues of the matrix/operator determines the allowed values of the corresponding observable. The energy levels of atoms, for example, are eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian operator. This is another completely radical shift from how classical physics treats motion.4. Unification of particles and waves. A mathematical analysis of the Schrodinger equation reveals that it has wavelike solutions, and so particles propagate as waves. This means that we shouldn't picture particles as tiny spheres bouncing around their environment. The closest you can get to visualizing a particle is by visualizing its wave function. As stated previously in the first point above, the wave function assigns a complex number to each point in space. This field of complex numbers evolves in time. What does this evolution look like? Well, if you are familiar with phasors, it looks like a field of rapidly rotating phasors (excellent visualization). To be more specific, the field of phasors for a particular particle looks like a screw that twists in the direction of motion.5. The time-dependent Schrodinger equation replaces Newton's second law.6. Measurement is random. Even if you have full knowledge of a quantum system prior to measurement (i.e. you know Ψ(x,t)Ψ(x,t)), you still will not be able to predict the outcomes of measurements in general. The outcome of the measurement is probabilistic. The possible outcomes are determined by the eigenvalues of the operator you are observing (see point 3), and the probability of each outcome is determined by the projection of the wave function onto the eigenvectors of that operator.

Quantum computing, for example, is one ramification that hasn't quite yet materialized. The philosophical and technological ramifications will most certainly continue to transform the 21st century in extraordinary ways.

1. In classical theory, a body always chooses the least action path and there is only one path. In Quantum theory, a particle also always chooses the least action path and it chooses multiple least action paths simultaneously.2. If there are 9 boxes and 10 pigeons, then at least one box will end up with two pigeons. This is in Classical Theory. No such thing happens in Quantum Theory. We can pass infinite electrons just from two boxes.3. We can determine position and velocity of a particle simultaneously with great accuracy in Classical Physics. Quantum Physics follows the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.4. Classical Physics is applicable to macroscopic particles. Quantum Physics is applicable to microscopic particles.

*The word eigen is German for “own”, “particular”, or “proper.” so when combined with value, it can be thought of as the “the particular value”, the value that's “just right” for the situation at hand.Eigenvalues and eigenvectors feature prominently in the analysis of linear transformations. The prefix eigen- is adopted from the German word eigen (cognate with the English word own) for "proper", "characteristic", "own".Originally used to study principal axes of the rotational motion of rigid bodies, eigenvalues and eigenvectors have a wide range of applications, for example in stability analysis, vibration analysis, atomic orbitals, facial recognition, and matrix diagonalization.

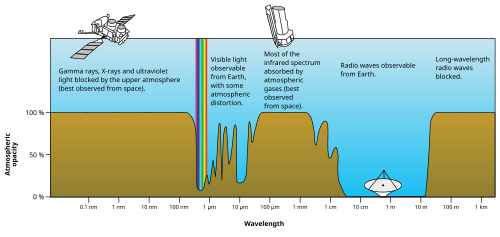

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EM radiation or EMR) refers to the waves (or their quanta, photons) of the electromagnetic field, propagating through space, carrying electromagnetic radiant energy.[1] It includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared, (visible) light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays. All of these waves form part of the electromagnetic spectrum.[2]

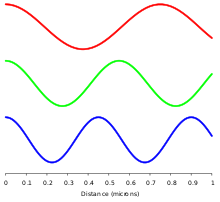

Classically, electromagnetic radiation consists of electromagnetic waves, which are synchronized oscillations of electric and magnetic fields. Electromagnetic radiation or electromagnetic waves are created due to periodic change of electric or magnetic field. Depending on how this periodic change occurs and the power generated, different wavelengths of electromagnetic spectrum are produced. In a vacuum, electromagnetic waves travel at the speed of light, commonly denoted c. In homogeneous, isotropic media, the oscillations of the two fields are perpendicular to each other and perpendicular to the direction of energy and wave propagation, forming a transverse wave. The wavefront of electromagnetic waves emitted from a point source (such as a light bulb) is a sphere. The position of an electromagnetic wave within the electromagnetic spectrum can be characterized by either its frequency of oscillation or its wavelength. Electromagnetic waves of different frequency are called by different names since they have different sources and effects on matter. In order of increasing frequency and decreasing wavelength these are: radio waves, microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet radiation, X-rays and gamma rays.[3]

Electromagnetic waves are emitted by electrically charged particles undergoing acceleration,[4][5] and these waves can subsequently interact with other charged particles, exerting force on them. EM waves carry energy, momentum and angular momentum away from their source particle and can impart those quantities to matter with which they interact. Electromagnetic radiation is associated with those EM waves that are free to propagate themselves ("radiate") without the continuing influence of the moving charges that produced them, because they have achieved sufficient distance from those charges. Thus, EMR is sometimes referred to as the far field. In this language, the near field refers to EM fields near the charges and current that directly produced them, specifically electromagnetic induction and electrostatic induction phenomena.

In quantum mechanics, an alternate way of viewing EMR is that it consists of photons, uncharged elementary particles with zero rest mass which are the quanta of the electromagnetic field, responsible for all electromagnetic interactions.[6] Quantum electrodynamics is the theory of how EMR interacts with matter on an atomic level.[7] Quantum effects provide additional sources of EMR, such as the transition of electrons to lower energy levels in an atom and black-body radiation.[8] The energy of an individual photon is quantized and is greater for photons of higher frequency. This relationship is given by Planck's equation E = hf, where E is the energy per photon, f is the frequency of the photon, and h is Planck's constant. A single gamma ray photon, for example, might carry ~100,000 times the energy of a single photon of visible light.

The effects of EMR upon chemical compounds and biological organisms depend both upon the radiation's power and its frequency. EMR of visible or lower frequencies (i.e., visible light, infrared, microwaves, and radio waves) is called non-ionizing radiation, because its photons do not individually have enough energy to ionize atoms or molecules or break chemical bonds. The effects of these radiations on chemical systems and living tissue are caused primarily by heating effects from the combined energy transfer of many photons. In contrast, high frequency ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays are called ionizing radiation, since individual photons of such high frequency have enough energy to ionize molecules or break chemical bonds. These radiations have the ability to cause chemical reactions and damage living cells beyond that resulting from simple heating, and can be a health hazard.

Theory

James Clerk Maxwell derived a wave form of the electric and magnetic equations, thus uncovering the wave-like nature of electric and magnetic fields and their symmetry. Because the speed of EM waves predicted by the wave equation coincided with the measured speed of light, Maxwell concluded that light itself is an EM wave.[9][10] Maxwell's equations were confirmed by Heinrich Hertz through experiments with radio waves.

[11] Maxwell realized that since a lot of physics is symmetrical and mathematically artistic in a way, that there must also be a symmetry between electricity and magnetism. He realized that light is a combination of electricity and magnetism and thus that the two must be tied together. According to Maxwell's equations, a spatially varying electric field is always associated with a magnetic field that changes over time.[12] Likewise, a spatially varying magnetic field is associated with specific changes over time in the electric field. In an electromagnetic wave, the changes in the electric field are always accompanied by a wave in the magnetic field in one direction, and vice versa. This relationship between the two occurs without either type of field causing the other; rather, they occur together in the same way that time and space changes occur together and are interlinked in special relativity. In fact, magnetic fields can be viewed as electric fields in another frame of reference, and electric fields can be viewed as magnetic fields in another frame of reference, but they have equal significance as physics is the same in all frames of reference, so the close relationship between space and time changes here is more than an analogy. Together, these fields form a propagating electromagnetic wave, which moves out into space and need never again interact with the source. The distant EM field formed in this way by the acceleration of a charge carries energy with it that "radiates" away through space, hence the term.

Maxwell's equations established that some charges and currents ("sources") produce a local type of electromagnetic field near them that does not have the behaviour of EMR. Currents directly produce a magnetic field, but it is of a magnetic dipole type that dies out with distance from the current. In a similar manner, moving charges pushed apart in a conductor by a changing electrical potential (such as in an antenna) produce an electric dipole type electrical field, but this also declines with distance. These fields make up the near-field near the EMR source. Neither of these behaviours are responsible for EM radiation. Instead, they cause electromagnetic field behaviour that only efficiently transfers power to a receiver very close to the source, such as the magnetic induction inside a transformer, or the feedback behaviour that happens close to the coil of a metal detector. Typically, near-fields have a powerful effect on their own sources, causing an increased "load" (decreased electrical reactance) in the source or transmitter, whenever energy is withdrawn from the EM field by a receiver. Otherwise, these fields do not "propagate" freely out into space, carrying their energy away without distance-limit, but rather oscillate, returning their energy to the transmitter if it is not received by a receiver.[citation needed]

By contrast, the EM far-field is composed of radiation that is free of the transmitter in the sense that (unlike the case in an electrical transformer) the transmitter requires the same power to send these changes in the fields out, whether the signal is immediately picked up or not. This distant part of the electromagnetic field is "electromagnetic radiation" (also called the far-field). The far-fields propagate (radiate) without allowing the transmitter to affect them. This causes them to be independent in the sense that their existence and their energy, after they have left the transmitter, is completely independent of both transmitter and receiver. Due to conservation of energy, the amount of power passing through any spherical surface drawn around the source is the same. Because such a surface has an area proportional to the square of its distance from the source, the power density of EM radiation always decreases with the inverse square of the distance from the source; this is called the inverse-square law. This is in contrast to dipole parts of the EM field close to the source (the near-field), which vary in power according to an inverse cube power law, and thus do not transport a conserved amount of energy over distances, but instead fade with distance, with its energy (as noted) rapidly returning to the transmitter or absorbed by a nearby receiver (such as a transformer secondary coil).

The far-field (EMR) depends on a different mechanism for its production than the near-field, and upon different terms in Maxwell's equations. Whereas the magnetic part of the near-field is due to currents in the source, the magnetic field in EMR is due only to the local change in the electric field. In a similar way, while the electric field in the near-field is due directly to the charges and charge-separation in the source, the electric field in EMR is due to a change in the local magnetic field. Both processes for producing electric and magnetic EMR fields have a different dependence on distance than do near-field dipole electric and magnetic fields. That is why the EMR type of EM field becomes dominant in power "far" from sources. The term "far from sources" refers to how far from the source (moving at the speed of light) any portion of the outward-moving EM field is located, by the time that source currents are changed by the varying source potential, and the source has therefore begun to generate an outwardly moving EM field of a different phase.[citation needed]

A more compact view of EMR is that the far-field that composes EMR is generally that part of the EM field that has traveled sufficient distance from the source, that it has become completely disconnected from any feedback to the charges and currents that were originally responsible for it. Now independent of the source charges, the EM field, as it moves farther away, is dependent only upon the accelerations of the charges that produced it. It no longer has a strong connection to the direct fields of the charges, or to the velocity of the charges (currents).[citation needed]

In the Liénard–Wiechert potential formulation of the electric and magnetic fields due to motion of a single particle (according to Maxwell's equations), the terms associated with acceleration of the particle are those that are responsible for the part of the field that is regarded as electromagnetic radiation. By contrast, the term associated with the changing static electric field of the particle and the magnetic term that results from the particle's uniform velocity, are both associated with the electromagnetic near-field, and do not comprise EM radiation.[citation needed]

Electrodynamics is the physics of electromagnetic radiation, and electromagnetism is the physical phenomenon associated with the theory of electrodynamics. Electric and magnetic fields obey the properties of superposition. Thus, a field due to any particular particle or time-varying electric or magnetic field contributes to the fields present in the same space due to other causes. Further, as they are vector fields, all magnetic and electric field vectors add together according to vector addition.[13] For example, in optics two or more coherent light waves may interact and by constructive or destructive interference yield a resultant irradiance deviating from the sum of the component irradiances of the individual light waves.[citation needed]

The electromagnetic fields of light are not affected by traveling through static electric or magnetic fields in a linear medium such as a vacuum. However, in nonlinear media, such as some crystals, interactions can occur between light and static electric and magnetic fields—these interactions include the Faraday effect and the Kerr effect.[14][15]

In refraction, a wave crossing from one medium to another of different density alters its speed and direction upon entering the new medium. The ratio of the refractive indices of the media determines the degree of refraction, and is summarized by Snell's law. Light of composite wavelengths (natural sunlight) disperses into a visible spectrum passing through a prism, because of the wavelength-dependent refractive index of the prism material (dispersion); that is, each component wave within the composite light is bent a different amount.[16]

EM radiation exhibits both wave properties and particle properties at the same time (see wave-particle duality). Both wave and particle characteristics have been confirmed in many experiments. Wave characteristics are more apparent when EM radiation is measured over relatively large timescales and over large distances while particle characteristics are more evident when measuring small timescales and distances. For example, when electromagnetic radiation is absorbed by matter, particle-like properties will be more obvious when the average number of photons in the cube of the relevant wavelength is much smaller than 1. It is not so difficult to experimentally observe non-uniform deposition of energy when light is absorbed, however this alone is not evidence of "particulate" behavior. Rather, it reflects the quantum nature of matter.[17] Demonstrating that the light itself is quantized, not merely its interaction with matter, is a more subtle affair.

Some experiments display both the wave and particle natures of electromagnetic waves, such as the self-interference of a single photon.[18] When a single photon is sent through an interferometer, it passes through both paths, interfering with itself, as waves do, yet is detected by a photomultiplier or other sensitive detector only once.

A quantum theory of the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter such as electrons is described by the theory of quantum electrodynamics.

Electromagnetic waves can be polarized, reflected, refracted, diffracted or interfere with each other.[19][20][21]

In homogeneous, isotropic media, electromagnetic radiation is a transverse wave,[22] meaning that its oscillations are perpendicular to the direction of energy transfer and travel. The electric and magnetic parts of the field stand in a fixed ratio of strengths to satisfy the two Maxwell equations that specify how one is produced from the other. In dissipation-less (lossless) media, these E and B fields are also in phase, with both reaching maxima and minima at the same points in space (see illustrations). A common misconception[citation needed] is that the E and B fields in electromagnetic radiation are out of phase because a change in one produces the other, and this would produce a phase difference between them as sinusoidal functions (as indeed happens in electromagnetic induction, and in the near-field close to antennas). However, in the far-field EM radiation which is described by the two source-free Maxwell curl operator equations, a more correct description is that a time-change in one type of field is proportional to a space-change in the other. These derivatives require that the E and B fields in EMR are in-phase (see mathematics section below).[citation needed]

An important aspect of light's nature is its frequency. The frequency of a wave is its rate of oscillation and is measured in hertz, the SI unit of frequency, where one hertz is equal to one oscillation per second. Light usually has multiple frequencies that sum to form the resultant wave. Different frequencies undergo different angles of refraction, a phenomenon known as dispersion.

A monochromatic wave (a wave of a single frequency) consists of successive troughs and crests, and the distance between two adjacent crests or troughs is called the wavelength. Waves of the electromagnetic spectrum vary in size, from very long radio waves longer than a continent to very short gamma rays smaller than atom nuclei. Frequency is inversely proportional to wavelength, according to the equation:[23]

where v is the speed of the wave (c in a vacuum or less in other media), f is the frequency and λ is the wavelength. As waves cross boundaries between different media, their speeds change but their frequencies remain constant.

Electromagnetic waves in free space must be solutions of Maxwell's electromagnetic wave equation. Two main classes of solutions are known, namely plane waves and spherical waves. The plane waves may be viewed as the limiting case of spherical waves at a very large (ideally infinite) distance from the source. Both types of waves can have a waveform which is an arbitrary time function (so long as it is sufficiently differentiable to conform to the wave equation). As with any time function, this can be decomposed by means of Fourier analysis into its frequency spectrum, or individual sinusoidal components, each of which contains a single frequency, amplitude and phase. Such a component wave is said to be monochromatic. A monochromatic electromagnetic wave can be characterized by its frequency or wavelength, its peak amplitude, its phase relative to some reference phase, its direction of propagation, and its polarization.

Interference is the superposition of two or more waves resulting in a new wave pattern. If the fields have components in the same direction, they constructively interfere, while opposite directions cause destructive interference. An example of interference caused by EMR is electromagnetic interference (EMI) or as it is more commonly known as, radio-frequency interference (RFI).[citation needed] Additionally, multiple polarization signals can be combined (i.e. interfered) to form new states of polarization, which is known as parallel polarization state generation.[24]

The energy in electromagnetic waves is sometimes called radiant energy.[25][26][27]

An anomaly arose in the late 19th century involving a contradiction between the wave theory of light and measurements of the electromagnetic spectra that were being emitted by thermal radiators known as black bodies. Physicists struggled with this problem unsuccessfully for many years. It later became known as the ultraviolet catastrophe. In 1900, Max Planck developed a new theory of black-body radiation that explained the observed spectrum. Planck's theory was based on the idea that black bodies emit light (and other electromagnetic radiation) only as discrete bundles or packets of energy. These packets were called quanta. In 1905, Albert Einstein proposed that light quanta be regarded as real particles. Later the particle of light was given the name photon, to correspond with other particles being described around this time, such as the electron and proton. A photon has an energy, E, proportional to its frequency, f, by

where h is Planck's constant,

Likewise, the momentum p of a photon is also proportional to its frequency and inversely proportional to its wavelength:

The source of Einstein's proposal that light was composed of particles (or could act as particles in some circumstances) was an experimental anomaly not explained by the wave theory: the photoelectric effect, in which light striking a metal surface ejected electrons from the surface, causing an electric current to flow across an applied voltage. Experimental measurements demonstrated that the energy of individual ejected electrons was proportional to the frequency, rather than the intensity, of the light. Furthermore, below a certain minimum frequency, which depended on the particular metal, no current would flow regardless of the intensity. These observations appeared to contradict the wave theory, and for years physicists tried in vain to find an explanation. In 1905, Einstein explained this puzzle by resurrecting the particle theory of light to explain the observed effect. Because of the preponderance of evidence in favor of the wave theory, however, Einstein's ideas were met initially with great skepticism among established physicists. Eventually Einstein's explanation was accepted as new particle-like behavior of light was observed, such as the Compton effect.[citation needed][30]

As a photon is absorbed by an atom, it excites the atom, elevating an electron to a higher energy level (one that is on average farther from the nucleus). When an electron in an excited molecule or atom descends to a lower energy level, it emits a photon of light at a frequency corresponding to the energy difference. Since the energy levels of electrons in atoms are discrete, each element and each molecule emits and absorbs its own characteristic frequencies. Immediate photon emission is called fluorescence, a type of photoluminescence. An example is visible light emitted from fluorescent paints, in response to ultraviolet (blacklight). Many other fluorescent emissions are known in spectral bands other than visible light. Delayed emission is called phosphorescence.[31][32]

The modern theory that explains the nature of light includes the notion of wave–particle duality. More generally, the theory states that everything has both a particle nature and a wave nature, and various experiments can be done to bring out one or the other. The particle nature is more easily discerned using an object with a large mass. A bold proposition by Louis de Broglie in 1924 led the scientific community to realize that matter (e.g. electrons) also exhibits wave–particle duality.[33]

Together, wave and particle effects fully explain the emission and absorption spectra of EM radiation. The matter-composition of the medium through which the light travels determines the nature of the absorption and emission spectrum. These bands correspond to the allowed energy levels in the atoms. Dark bands in the absorption spectrum are due to the atoms in an intervening medium between source and observer. The atoms absorb certain frequencies of the light between emitter and detector/eye, then emit them in all directions. A dark band appears to the detector, due to the radiation scattered out of the beam. For instance, dark bands in the light emitted by a distant star are due to the atoms in the star's atmosphere. A similar phenomenon occurs for emission, which is seen when an emitting gas glows due to excitation of the atoms from any mechanism, including heat. As electrons descend to lower energy levels, a spectrum is emitted that represents the jumps between the energy levels of the electrons, but lines are seen because again emission happens only at particular energies after excitation.[34] An example is the emission spectrum of nebulae.[citation needed] Rapidly moving electrons are most sharply accelerated when they encounter a region of force, so they are responsible for producing much of the highest frequency electromagnetic radiation observed in nature.

These phenomena can aid various chemical determinations for the composition of gases lit from behind (absorption spectra) and for glowing gases (emission spectra). Spectroscopy (for example) determines what chemical elements comprise a particular star. Spectroscopy is also used in the determination of the distance of a star, using the red shift.[35]

When any wire (or other conducting object such as an antenna) conducts alternating current, electromagnetic radiation is propagated at the same frequency as the current. In many such situations it is possible to identify an electrical dipole moment that arises from separation of charges due to the exciting electrical potential, and this dipole moment oscillates in time, as the charges move back and forth. This oscillation at a given frequency gives rise to changing electric and magnetic fields, which then set the electromagnetic radiation in motion.[citation needed]

At the quantum level, electromagnetic radiation is produced when the wavepacket of a charged particle oscillates or otherwise accelerates. Charged particles in a stationary state do not move, but a superposition of such states may result in a transition state that has an electric dipole moment that oscillates in time. This oscillating dipole moment is responsible for the phenomenon of radiative transition between quantum states of a charged particle. Such states occur (for example) in atoms when photons are radiated as the atom shifts from one stationary state to another.[citation needed]

As a wave, light is characterized by a velocity (the speed of light), wavelength, and frequency. As particles, light is a stream of photons. Each has an energy related to the frequency of the wave given by Planck's relation E = hf, where E is the energy of the photon, h is Planck's constant, 6.626 × 10−34 J·s, and f is the frequency of the wave.[36]

One rule is obeyed regardless of circumstances: EM radiation in a vacuum travels at the speed of light, relative to the observer, regardless of the observer's velocity. (This observation led to Einstein's development of the theory of special relativity.)[citation needed] In a medium (other than vacuum), velocity factor or refractive index are considered, depending on frequency and application. Both of these are ratios of the speed in a medium to speed in a vacuum.[citation needed]

By the late nineteenth century, various experimental anomalies could not be explained by the simple wave theory. One of these anomalies involved a controversy over the speed of light. The speed of light and other EMR predicted by Maxwell's equations did not appear unless the equations were modified in a way first suggested by FitzGerald and Lorentz (see history of special relativity), or else otherwise that speed would depend on the speed of observer relative to the "medium" (called luminiferous aether) which supposedly "carried" the electromagnetic wave (in a manner analogous to the way air carries sound waves). Experiments failed to find any observer effect. In 1905, Einstein proposed that space and time appeared to be velocity-changeable entities for light propagation and all other processes and laws. These changes accounted for the constancy of the speed of light and all electromagnetic radiation, from the viewpoints of all observers—even those in relative motion.

Electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths other than those of visible light were discovered in the early 19th century. The discovery of infrared radiation is ascribed to astronomer William Herschel, who published his results in 1800 before the Royal Society of London.[37] Herschel used a glass prism to refract light from the Sun and detected invisible rays that caused heating beyond the red part of the spectrum, through an increase in the temperature recorded with a thermometer. These "calorific rays" were later termed infrared.[38]

In 1801, German physicist Johann Wilhelm Ritter discovered ultraviolet in an experiment similar to Herschel's, using sunlight and a glass prism. Ritter noted that invisible rays near the violet edge of a solar spectrum dispersed by a triangular prism darkened silver chloride preparations more quickly than did the nearby violet light. Ritter's experiments were an early precursor to what would become photography. Ritter noted that the ultraviolet rays (which at first were called "chemical rays") were capable of causing chemical reactions.[39]

In 1862–64 James Clerk Maxwell developed equations for the electromagnetic field which suggested that waves in the field would travel with a speed that was very close to the known speed of light. Maxwell therefore suggested that visible light (as well as invisible infrared and ultraviolet rays by inference) all consisted of propagating disturbances (or radiation) in the electromagnetic field. Radio waves were first produced deliberately by Heinrich Hertz in 1887, using electrical circuits calculated to produce oscillations at a much lower frequency than that of visible light, following recipes for producing oscillating charges and currents suggested by Maxwell's equations. Hertz also developed ways to detect these waves, and produced and characterized what were later termed radio waves and microwaves.[40]:286,7

Wilhelm Röntgen discovered and named X-rays. After experimenting with high voltages applied to an evacuated tube on 8 November 1895, he noticed a fluorescence on a nearby plate of coated glass. In one month, he discovered X-rays' main properties.[40]:307

The last portion of the EM spectrum to be discovered was associated with radioactivity. Henri Becquerel found that uranium salts caused fogging of an unexposed photographic plate through a covering paper in a manner similar to X-rays, and Marie Curie discovered that only certain elements gave off these rays of energy, soon discovering the intense radiation of radium. The radiation from pitchblende was differentiated into alpha rays (alpha particles) and beta rays (beta particles) by Ernest Rutherford through simple experimentation in 1899, but these proved to be charged particulate types of radiation. However, in 1900 the French scientist Paul Villard discovered a third neutrally charged and especially penetrating type of radiation from radium, and after he described it, Rutherford realized it must be yet a third type of radiation, which in 1903 Rutherford named gamma rays. In 1910 British physicist William Henry Bragg demonstrated that gamma rays are electromagnetic radiation, not particles, and in 1914 Rutherford and Edward Andrade measured their wavelengths, finding that they were similar to X-rays but with shorter wavelengths and higher frequency, although a 'cross-over' between X and gamma rays makes it possible to have X-rays with a higher energy (and hence shorter wavelength) than gamma rays and vice versa. The origin of the ray differentiates them, gamma rays tend to be natural phenomena originating from the unstable nucleus of an atom and X-rays are electrically generated (and hence man-made) unless they are as a result of bremsstrahlung X-radiation caused by the interaction of fast moving particles (such as beta particles) colliding with certain materials, usually of higher atomic numbers.[40]:308,9

EM radiation (the designation 'radiation' excludes static electric and magnetic and near fields) is classified by wavelength into radio, microwave, infrared, visible, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. Arbitrary electromagnetic waves can be expressed by Fourier analysis in terms of sinusoidal monochromatic waves, which in turn can each be classified into these regions of the EMR spectrum.

For certain classes of EM waves, the waveform is most usefully treated as random, and then spectral analysis must be done by slightly different mathematical techniques appropriate to random or stochastic processes. In such cases, the individual frequency components are represented in terms of their power content, and the phase information is not preserved. Such a representation is called the power spectral density of the random process. Random electromagnetic radiation requiring this kind of analysis is, for example, encountered in the interior of stars, and in certain other very wideband forms of radiation such as the Zero point wave field of the electromagnetic vacuum.

The behavior of EM radiation and its interaction with matter depends on its frequency, and changes qualitatively as the frequency changes. Lower frequencies have longer wavelengths, and higher frequencies have shorter wavelengths, and are associated with photons of higher energy. There is no fundamental limit known to these wavelengths or energies, at either end of the spectrum, although photons with energies near the Planck energy or exceeding it (far too high to have ever been observed) will require new physical theories to describe.

Radio waves have the least amount of energy and the lowest frequency. When radio waves impinge upon a conductor, they couple to the conductor, travel along it and induce an electric current on the conductor surface by moving the electrons of the conducting material in correlated bunches of charge. Such effects can cover macroscopic distances in conductors (such as radio antennas), since the wavelength of radiowaves is long.

Electromagnetic radiation phenomena with wavelengths ranging from as long as one meter to as short as one millimeter are called microwaves; with frequencies between 300 MHz (0.3 GHz) and 300 GHz.

At radio and microwave frequencies, EMR interacts with matter largely as a bulk collection of charges which are spread out over large numbers of affected atoms. In electrical conductors, such induced bulk movement of charges (electric currents) results in absorption of the EMR, or else separations of charges that cause generation of new EMR (effective reflection of the EMR). An example is absorption or emission of radio waves by antennas, or absorption of microwaves by water or other molecules with an electric dipole moment, as for example inside a microwave oven. These interactions produce either electric currents or heat, or both.

Like radio and microwave, infrared (IR) also is reflected by metals (and also most EMR, well into the ultraviolet range). However, unlike lower-frequency radio and microwave radiation, Infrared EMR commonly interacts with dipoles present in single molecules, which change as atoms vibrate at the ends of a single chemical bond. It is consequently absorbed by a wide range of substances, causing them to increase in temperature as the vibrations dissipate as heat. The same process, run in reverse, causes bulk substances to radiate in the infrared spontaneously (see thermal radiation section below).

Infrared radiation is divided into spectral subregions. While different subdivision schemes exist,[41][42] the spectrum is commonly divided as near-infrared (0.75–1.4 μm), short-wavelength infrared (1.4–3 μm), mid-wavelength infrared (3–8 μm), long-wavelength infrared (8–15 μm) and far infrared (15–1000 μm).[43]

Natural sources produce EM radiation across the spectrum. EM radiation with a wavelength between approximately 400 nm and 700 nm is directly detected by the human eye and perceived as visible light. Other wavelengths, especially nearby infrared (longer than 700 nm) and ultraviolet (shorter than 400 nm) are also sometimes referred to as light.

As frequency increases into the visible range, photons have enough energy to change the bond structure of some individual molecules. It is not a coincidence that this happens in the visible range, as the mechanism of vision involves the change in bonding of a single molecule, retinal, which absorbs a single photon. The change in retinal, causes a change in the shape of the rhodopsin protein it is contained in, which starts the biochemical process that causes the retina of the human eye to sense the light.

Photosynthesis becomes possible in this range as well, for the same reason. A single molecule of chlorophyll is excited by a single photon. In plant tissues that conduct photosynthesis, carotenoids act to quench electronically excited chlorophyll produced by visible light in a process called non-photochemical quenching, to prevent reactions that would otherwise interfere with photosynthesis at high light levels.

Animals that detect infrared make use of small packets of water that change temperature, in an essentially thermal process that involves many photons.

Infrared, microwaves and radio waves are known to damage molecules and biological tissue only by bulk heating, not excitation from single photons of the radiation.

Visible light is able to affect only a tiny percentage of all molecules. Usually not in a permanent or damaging way, rather the photon excites an electron which then emits another photon when returning to its original position. This is the source of color produced by most dyes. Retinal is an exception. When a photon is absorbed the retinal permanently changes structure from cis to trans, and requires a protein to convert it back, i.e. reset it to be able to function as a light detector again.

Limited evidence indicate that some reactive oxygen species are created by visible light in skin, and that these may have some role in photoaging, in the same manner as ultraviolet A.[44]

As frequency increases into the ultraviolet, photons now carry enough energy (about three electron volts or more) to excite certain doubly bonded molecules into permanent chemical rearrangement. In DNA, this causes lasting damage. DNA is also indirectly damaged by reactive oxygen species produced by ultraviolet A (UVA), which has energy too low to damage DNA directly. This is why ultraviolet at all wavelengths can damage DNA, and is capable of causing cancer, and (for UVB) skin burns (sunburn) that are far worse than would be produced by simple heating (temperature increase) effects. This property of causing molecular damage that is out of proportion to heating effects, is characteristic of all EMR with frequencies at the visible light range and above. These properties of high-frequency EMR are due to quantum effects that permanently damage materials and tissues at the molecular level.[citation needed]

At the higher end of the ultraviolet range, the energy of photons becomes large enough to impart enough energy to electrons to cause them to be liberated from the atom, in a process called photoionisation. The energy required for this is always larger than about 10 electron volt (eV) corresponding with wavelengths smaller than 124 nm (some sources suggest a more realistic cutoff of 33 eV, which is the energy required to ionize water). This high end of the ultraviolet spectrum with energies in the approximate ionization range, is sometimes called "extreme UV." Ionizing UV is strongly filtered by the Earth's atmosphere.[citation needed]

Electromagnetic radiation composed of photons that carry minimum-ionization energy, or more, (which includes the entire spectrum with shorter wavelengths), is therefore termed ionizing radiation. (Many other kinds of ionizing radiation are made of non-EM particles). Electromagnetic-type ionizing radiation extends from the extreme ultraviolet to all higher frequencies and shorter wavelengths, which means that all X-rays and gamma rays qualify. These are capable of the most severe types of molecular damage, which can happen in biology to any type of biomolecule, including mutation and cancer, and often at great depths below the skin, since the higher end of the X-ray spectrum, and all of the gamma ray spectrum, penetrate matter.

Most UV and X-rays are blocked by absorption first from molecular nitrogen, and then (for wavelengths in the upper UV) from the electronic excitation of dioxygen and finally ozone at the mid-range of UV. Only 30% of the Sun's ultraviolet light reaches the ground, and almost all of this is well transmitted.

Visible light is well transmitted in air, as it is not energetic enough to excite nitrogen, oxygen, or ozone, but too energetic to excite molecular vibrational frequencies of water vapor.[citation needed]

Absorption bands in the infrared are due to modes of vibrational excitation in water vapor. However, at energies too low to excite water vapor, the atmosphere becomes transparent again, allowing free transmission of most microwave and radio waves.[citation needed]

Finally, at radio wavelengths longer than 10 meters or so (about 30 MHz), the air in the lower atmosphere remains transparent to radio, but plasma in certain layers of the ionosphere begins to interact with radio waves (see skywave). This property allows some longer wavelengths (100 meters or 3 MHz) to be reflected and results in shortwave radio beyond line-of-sight. However, certain ionospheric effects begin to block incoming radiowaves from space, when their frequency is less than about 10 MHz (wavelength longer than about 30 meters).[45]

The basic structure of matter involves charged particles bound together. When electromagnetic radiation impinges on matter, it causes the charged particles to oscillate and gain energy. The ultimate fate of this energy depends on the context. It could be immediately re-radiated and appear as scattered, reflected, or transmitted radiation. It may get dissipated into other microscopic motions within the matter, coming to thermal equilibrium and manifesting itself as thermal energy, or even kinetic energy, in the material. With a few exceptions related to high-energy photons (such as fluorescence, harmonic generation, photochemical reactions, the photovoltaic effect for ionizing radiations at far ultraviolet, X-ray and gamma radiation), absorbed electromagnetic radiation simply deposits its energy by heating the material. This happens for infrared, microwave and radio wave radiation. Intense radio waves can thermally burn living tissue and can cook food. In addition to infrared lasers, sufficiently intense visible and ultraviolet lasers can easily set paper afire.[46][citation needed]

Ionizing radiation creates high-speed electrons in a material and breaks chemical bonds, but after these electrons collide many times with other atoms eventually most of the energy becomes thermal energy all in a tiny fraction of a second. This process makes ionizing radiation far more dangerous per unit of energy than non-ionizing radiation. This caveat also applies to UV, even though almost all of it is not ionizing, because UV can damage molecules due to electronic excitation, which is far greater per unit energy than heating effects.[46][citation needed]

Infrared radiation in the spectral distribution of a black body is usually considered a form of heat, since it has an equivalent temperature and is associated with an entropy change per unit of thermal energy. However, "heat" is a technical term in physics and thermodynamics and is often confused with thermal energy. Any type of electromagnetic energy can be transformed into thermal energy in interaction with matter. Thus, any electromagnetic radiation can "heat" (in the sense of increase the thermal energy temperature of) a material, when it is absorbed.[47]

The inverse or time-reversed process of absorption is thermal radiation. Much of the thermal energy in matter consists of random motion of charged particles, and this energy can be radiated away from the matter. The resulting radiation may subsequently be absorbed by another piece of matter, with the deposited energy heating the material.[48]

The electromagnetic radiation in an opaque cavity at thermal equilibrium is effectively a form of thermal energy, having maximum radiation entropy.[49]

Bioelectromagnetics is the study of the interactions and effects of EM radiation on living organisms. The effects of electromagnetic radiation upon living cells, including those in humans, depends upon the radiation's power and frequency. For low-frequency radiation (radio waves to visible light) the best-understood effects are those due to radiation power alone, acting through heating when radiation is absorbed. For these thermal effects, frequency is important as it affects the intensity of the radiation and penetration into the organism (for example, microwaves penetrate better than infrared). It is widely accepted that low frequency fields that are too weak to cause significant heating could not possibly have any biological effect.[50]

Despite the commonly accepted results, some research has been conducted to show that weaker non-thermal electromagnetic fields, (including weak ELF magnetic fields, although the latter does not strictly qualify as EM radiation[50][51][52]), and modulated RF and microwave fields have biological effects.[53][54][55] Fundamental mechanisms of the interaction between biological material and electromagnetic fields at non-thermal levels are not fully understood.[50]

The World Health Organization has classified radio frequency electromagnetic radiation as Group 2B - possibly carcinogenic.[56][57] This group contains possible carcinogens such as lead, DDT, and styrene. For example, epidemiological studies looking for a relationship between cell phone use and brain cancer development, have been largely inconclusive, save to demonstrate that the effect, if it exists, cannot be a large one.

At higher frequencies (visible and beyond), the effects of individual photons begin to become important, as these now have enough energy individually to directly or indirectly damage biological molecules.[58] All UV frequences have been classed as Group 1 carcinogens by the World Health Organization. Ultraviolet radiation from sun exposure is the primary cause of skin cancer.[59][60]

Thus, at UV frequencies and higher (and probably somewhat also in the visible range),[44] electromagnetic radiation does more damage to biological systems than simple heating predicts. This is most obvious in the "far" (or "extreme") ultraviolet. UV, with X-ray and gamma radiation, are referred to as ionizing radiation due to the ability of photons of this radiation to produce ions and free radicals in materials (including living tissue). Since such radiation can severely damage life at energy levels that produce little heating, it is considered far more dangerous (in terms of damage-produced per unit of energy, or power) than the rest of the electromagnetic spectrum.

* * * * * * * *

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

show Background |

show Tools |

show Equations |

show Incomplete theories |

show Scientists |

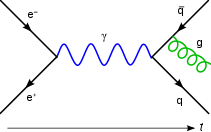

In particle physics, quantum electrodynamics (QED) is the relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics. In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quantum mechanics and special relativity is achieved. QED mathematically describes all phenomena involving electrically charged particles interacting by means of exchange of photons and represents the quantum counterpart of classical electromagnetism giving a complete account of matter and light interaction.

In technical terms, QED can be described as a perturbation theory of the electromagnetic quantum vacuum. Richard Feynman called it "the jewel of physics" for its extremely accurate predictions of quantities like the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron and the Lamb shift of the energy levels of hydrogen.[1]:Ch1

The first formulation of a quantum theory describing radiation and matter interaction is attributed to British scientist Paul Dirac, who (during the 1920s) was able to compute the coefficient of spontaneous emission of an atom.[2]

Dirac described the quantization of the electromagnetic field as an ensemble of harmonic oscillators with the introduction of the concept of creation and annihilation operators of particles. In the following years, with contributions from Wolfgang Pauli, Eugene Wigner, Pascual Jordan, Werner Heisenberg and an elegant formulation of quantum electrodynamics due to Enrico Fermi,[3] physicists came to believe that, in principle, it would be possible to perform any computation for any physical process involving photons and charged particles. However, further studies by Felix Bloch with Arnold Nordsieck,[4] and Victor Weisskopf,[5] in 1937 and 1939, revealed that such computations were reliable only at a first order of perturbation theory, a problem already pointed out by Robert Oppenheimer.[6] At higher orders in the series infinities emerged, making such computations meaningless and casting serious doubts on the internal consistency of the theory itself. With no solution for this problem known at the time, it appeared that a fundamental incompatibility existed between special relativity and quantum mechanics.

Difficulties with the theory increased through the end of the 1940s. Improvements in microwave technology made it possible to take more precise measurements of the shift of the levels of a hydrogen atom,[7] now known as the Lamb shift and magnetic moment of the electron.[8] These experiments exposed discrepancies which the theory was unable to explain.

A first indication of a possible way out was given by Hans Bethe in 1947,[9] after attending the Shelter Island Conference.[10] While he was traveling by train from the conference to Schenectady he made the first non-relativistic computation of the shift of the lines of the hydrogen atom as measured by Lamb and Retherford.[9] Despite the limitations of the computation, agreement was excellent. The idea was simply to attach infinities to corrections of mass and charge that were actually fixed to a finite value by experiments. In this way, the infinities get absorbed in those constants and yield a finite result in good agreement with experiments. This procedure was named renormalization.

Based on Bethe's intuition and fundamental papers on the subject by Shin'ichirō Tomonaga,[11] Julian Schwinger,[12][13] Richard Feynman[14][15][16] and Freeman Dyson,[17][18] it was finally possible to get fully covariant formulations that were finite at any order in a perturbation series of quantum electrodynamics. Shin'ichirō Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger and Richard Feynman were jointly awarded with the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work in this area.[19] Their contributions, and those of Freeman Dyson, were about covariant and gauge-invariant formulations of quantum electrodynamics that allow computations of observables at any order of perturbation theory. Feynman's mathematical technique, based on his diagrams, initially seemed very different from the field-theoretic, operator-based approach of Schwinger and Tomonaga, but Freeman Dyson later showed that the two approaches were equivalent.[17] Renormalization, the need to attach a physical meaning at certain divergences appearing in the theory through integrals, has subsequently become one of the fundamental aspects of quantum field theory and has come to be seen as a criterion for a theory's general acceptability. Even though renormalization works very well in practice, Feynman was never entirely comfortable with its mathematical validity, even referring to renormalization as a "shell game" and "hocus pocus".[1]:128

QED has served as the model and template for all subsequent quantum field theories. One such subsequent theory is quantum chromodynamics, which began in the early 1960s and attained its present form in the 1970s work by H. David Politzer, Sidney Coleman, David Gross and Frank Wilczek. Building on the pioneering work of Schwinger, Gerald Guralnik, Dick Hagen, and Tom Kibble,[20][21] Peter Higgs, Jeffrey Goldstone, and others, Sheldon Lee Glashow, Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam independently showed how the weak nuclear force and quantum electrodynamics could be merged into a single electroweak force.

Near the end of his life, Richard Feynman gave a series of lectures on QED intended for the lay public. These lectures were transcribed and published as Feynman (1985), QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter,[1] a classic non-mathematical exposition of QED from the point of view articulated below.

The key components of Feynman's presentation of QED are three basic actions.[1]:85

These actions are represented in the form of visual shorthand by the three basic elements of Feynman diagrams: a wavy line for the photon, a straight line for the electron and a junction of two straight lines and a wavy one for a vertex representing emission or absorption of a photon by an electron. These can all be seen in the adjacent diagram.

As well as the visual shorthand for the actions Feynman introduces another kind of shorthand for the numerical quantities called probability amplitudes. The probability is the square of the absolute value of total probability amplitude,

QED is based on the assumption that complex interactions of many electrons and photons can be represented by fitting together a suitable collection of the above three building blocks and then using the probability amplitudes to calculate the probability of any such complex interaction. It turns out that the basic idea of QED can be communicated while assuming that the square of the total of the probability amplitudes mentioned above (P(A to B), E(C to D) and j) acts just like our everyday probability (a simplification made in Feynman's book). Later on, this will be corrected to include specifically quantum-style mathematics, following Feynman.

The basic rules of probability amplitudes that will be used are:[1]:93

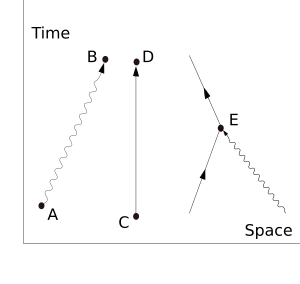

Suppose, we start with one electron at a certain place and time (this place and time being given the arbitrary label A) and a photon at another place and time (given the label B). A typical question from a physical standpoint is: "What is the probability of finding an electron at C (another place and a later time) and a photon at D (yet another place and time)?". The simplest process to achieve this end is for the electron to move from A to C (an elementary action) and for the photon to move from B to D (another elementary action). From a knowledge of the probability amplitudes of each of these sub-processes – E(A to C) and P(B to D) – we would expect to calculate the probability amplitude of both happening together by multiplying them, using rule b) above. This gives a simple estimated overall probability amplitude, which is squared to give an estimated probability.[citation needed]

But there are other ways in which the end result could come about. The electron might move to a place and time E, where it absorbs the photon; then move on before emitting another photon at F; then move on to C, where it is detected, while the new photon moves on to D. The probability of this complex process can again be calculated by knowing the probability amplitudes of each of the individual actions: three electron actions, two photon actions and two vertexes – one emission and one absorption. We would expect to find the total probability amplitude by multiplying the probability amplitudes of each of the actions, for any chosen positions of E and F. We then, using rule a) above, have to add up all these probability amplitudes for all the alternatives for E and F. (This is not elementary in practice and involves integration.) But there is another possibility, which is that the electron first moves to G, where it emits a photon, which goes on to D, while the electron moves on to H, where it absorbs the first photon, before moving on to C. Again, we can calculate the probability amplitude of these possibilities (for all points G and H). We then have a better estimation for the total probability amplitude by adding the probability amplitudes of these two possibilities to our original simple estimate. Incidentally, the name given to this process of a photon interacting with an electron in this way is Compton scattering.[citation needed]

There is an infinite number of other intermediate processes in which more and more photons are absorbed and/or emitted. For each of these possibilities, there is a Feynman diagram describing it. This implies a complex computation for the resulting probability amplitudes, but provided it is the case that the more complicated the diagram, the less it contributes to the result, it is only a matter of time and effort to find as accurate an answer as one wants to the original question. This is the basic approach of QED. To calculate the probability of any interactive process between electrons and photons, it is a matter of first noting, with Feynman diagrams, all the possible ways in which the process can be constructed from the three basic elements. Each diagram involves some calculation involving definite rules to find the associated probability amplitude.

That basic scaffolding remains when one moves to a quantum description, but some conceptual changes are needed. One is that whereas we might expect in our everyday life that there would be some constraints on the points to which a particle can move, that is not true in full quantum electrodynamics. There is a possibility of an electron at A, or a photon at B, moving as a basic action to any other place and time in the universe. That includes places that could only be reached at speeds greater than that of light and also earlier times. (An electron moving backwards in time can be viewed as a positron moving forward in time.)[1]:89, 98–99

Quantum mechanics introduces an important change in the way probabilities are computed. Probabilities are still represented by the usual real numbers we use for probabilities in our everyday world, but probabilities are computed as the square modulus of probability amplitudes, which are complex numbers.

Feynman avoids exposing the reader to the mathematics of complex numbers by using a simple but accurate representation of them as arrows on a piece of paper or screen. (These must not be confused with the arrows of Feynman diagrams, which are simplified representations in two dimensions of a relationship between points in three dimensions of space and one of time.) The amplitude arrows are fundamental to the description of the world given by quantum theory. They are related to our everyday ideas of probability by the simple rule that the probability of an event is the square of the length of the corresponding amplitude arrow. So, for a given process, if two probability amplitudes, v and w, are involved, the probability of the process will be given either by

or

The rules as regards adding or multiplying, however, are the same as above. But where you would expect to add or multiply probabilities, instead you add or multiply probability amplitudes that now are complex numbers.

Addition and multiplication are common operations in the theory of complex numbers and are given in the figures. The sum is found as follows. Let the start of the second arrow be at the end of the first. The sum is then a third arrow that goes directly from the beginning of the first to the end of the second. The product of two arrows is an arrow whose length is the product of the two lengths. The direction of the product is found by adding the angles that each of the two have been turned through relative to a reference direction: that gives the angle that the product is turned relative to the reference direction.

That change, from probabilities to probability amplitudes, complicates the mathematics without changing the basic approach. But that change is still not quite enough because it fails to take into account the fact that both photons and electrons can be polarized, which is to say that their orientations in space and time have to be taken into account. Therefore, P(A to B) consists of 16 complex numbers, or probability amplitude arrows.[1]:120–121 There are also some minor changes to do with the quantity j, which may have to be rotated by a multiple of 90° for some polarizations, which is only of interest for the detailed bookkeeping.

Associated with the fact that the electron can be polarized is another small necessary detail, which is connected with the fact that an electron is a fermion and obeys Fermi–Dirac statistics. The basic rule is that if we have the probability amplitude for a given complex process involving more than one electron, then when we include (as we always must) the complementary Feynman diagram in which we exchange two electron events, the resulting amplitude is the reverse – the negative – of the first. The simplest case would be two electrons starting at A and B ending at C and D. The amplitude would be calculated as the "difference", E(A to D) × E(B to C) − E(A to C) × E(B to D), where we would expect, from our everyday idea of probabilities, that it would be a sum.[1]:112–113

Finally, one has to compute P(A to B) and E(C to D) corresponding to the probability amplitudes for the photon and the electron respectively. These are essentially the solutions of the Dirac equation, which describe the behavior of the electron's probability amplitude and the Maxwell's equations, which describes the behavior of the photon's probability amplitude. These are called Feynman propagators. The translation to a notation commonly used in the standard literature is as follows:

where a shorthand symbol such as

A problem arose historically which held up progress for twenty years: although we start with the assumption of three basic "simple" actions, the rules of the game say that if we want to calculate the probability amplitude for an electron to get from A to B, we must take into account all the possible ways: all possible Feynman diagrams with those endpoints. Thus there will be a way in which the electron travels to C, emits a photon there and then absorbs it again at D before moving on to B. Or it could do this kind of thing twice, or more. In short, we have a fractal-like situation in which if we look closely at a line, it breaks up into a collection of "simple" lines, each of which, if looked at closely, are in turn composed of "simple" lines, and so on ad infinitum. This is a challenging situation to handle. If adding that detail only altered things slightly, then it would not have been too bad, but disaster struck when it was found that the simple correction mentioned above led to infinite probability amplitudes. In time this problem was "fixed" by the technique of renormalization. However, Feynman himself remained unhappy about it, calling it a "dippy process".[1]:128

Within the above framework physicists were then able to calculate to a high degree of accuracy some of the properties of electrons, such as the anomalous magnetic dipole moment. However, as Feynman points out, it fails to explain why particles such as the electron have the masses they do. "There is no theory that adequately explains these numbers. We use the numbers in all our theories, but we don't understand them – what they are, or where they come from. I believe that from a fundamental point of view, this is a very interesting and serious problem."[1]:152

* * * * * * * *

QUANTUM PHYSICS APPLICATIONS

Brain energy is associated commonly with electrochemical type of energy. This energy is displayed in the form of electromagnetic waves or better known as brainwaves. This concept is a classical concept (Newtonian) in which the studied object, that is the brain is viewed as a large anatomical object with its functional brainwaves. Another concept which incorporates quantum principles in it can also be used to study the brain. This perspective viewing the brain as purely waves, including its anatomical substrate. Thus, there are two types of energy or field exist in our brain: electromagnetic and quantum fields. Electromagnetic field is thought as dominant energy in purely motor and sensory inputs to our brain, whilst quantum field or energy is perceived as more influential in brain cognitions. The reason for this notion lies in its features which is diffused, non-deterministic, varied, complex and oneness.

Quantum physics is the branch of physics that deals with tiny objects and quantisation (packet of energy or interaction) of various entities. In contrast to classical Newtonian physics which deals with large objects, quantum physics or mechanics is a science of small scale objects such as atom and subatomic particles. In general, central elements of quantum physics are: i) particle-wave duality for quantum entity such as elementary particles, and even for compound particles, for instances, atoms and molecules; ii) quantum entanglement. It can be defined as a phenomenon in which the quantum states of two or more objects have to be described with reference to each other, even though the individual objects may be spatially separated; iii) coherence and decoherence. Coherence is referred to waves that have a constant phase difference, same frequency, or same waveform morphology, whilst decoherence means interference is present; iv) superposition. It is a complex property of a wave. In a wave, there could be many other smaller waves; v) quantum tunneling. It is a phenomenon where a quantum particle passes through a barrier; vi) quantum uncertainty. It is also known as Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. It states that the more precisely the position of some particle is determined, the less precisely its velocity can be known, and vice versa (1). Thus, quantum physics is seen as dealing with ambiguity in the physical world.

Based upon the first principle, human brain can be viewed entirely as either in particle or in wave form. The particle perspective portrays brain in anatomical form, whilst the wave perspective depicts the brain in wave form (2, 3). Waves of the brain can be classified further into two main entities: i) brainwaves that commonly detected or studied using electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG) and is based on electromagnetic principles; and ii) waves perspective of brain anatomical particles. The first waves or brainwaves can be named as electric waves with energy or field in it—thus stated here as electromagnetic field (EMF) and for the second waves, quantum waves or quantum field (QF) is used. Therefore, brain can be viewed as either i) anatomical brain with brainwaves (classical) or ii) all are waves with onefield or energy, but this field can be divided further into EMF (large object physics) and QF (small object physics). In this editorial commentary, the author describes briefly these two concepts of brain fields and invite readers to think of quantum physics as a science that not only capable in describing the behaviour of subatomic particles, but also behaviour of people (people mind).

A physiological principle states a neuron communicates with each other by using electrical signals. The electrical signal called action potential travels along the axon and triggers neurotransmitter at the synapse, hence further electrical signal can be passed to other neurons. With electrical signal, there is always a simultaneous presence of magnetic field. Thus, this type of communication is known as EMF communication (4–6). On the contrary the QF type of communication considers all brain elements are waves, thus the energy is still wavy (ups and downs) and perhaps in diffused pattern with more complex networks. In this perspective, EMF of the brain is viewed as arising from: i) a projected stimuli outside the brain such as our five senses of stimuli—seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling; or ii) the brain itself such as in virtual reality, dreaming and hypnosis (without external stimuli); and iii) non-cognition such as pure motor movements. On the other hand, brain QF is viewed as onefield or wholeness or oneness with our universe. Thus, it is commonly regarded as having one consciousness (7, 8). With this understanding, consciousness concept in quantum realm is not restricted only to human brain. In other words, we may say QF permeates whole of our universe. The quantum entity that suits this permeating energy concept is the light, whilst the non-quantum entity (Newtonian physics) that suits the focus or limited projection is electricity. Hence, EMF has electric feature whilst QF has light feature. This is summarised in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Limited consciousness for the brain and limited projection for the universe form a principle for the collapse of wave function of the particle. Brain and universe are permeated by quantum field, whilst electromagnetic field inside the brain arises from a discrete or limited projection from our universe

General features of brain EMF and brain QF

| Feature | EMF | QF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wave pattern | Presence of pilot/directional wave | Diffused waves |

| 2 | Wave characteristics | High frequency wave | Low frequency wave |

| 3 | Wavelength | Short wavelength | Long wavelength |

| 4 | Quantum concept | Deterministic (locatable) | Non-deterministic (unlocatable, varied) |

| 5 | Dimension | High dimension (electric) | Low dimension (light) |

| 6 | Physics concept | Bohmian mechanics | Quantum mechanics |

| 7 | Brain network | Simple network (few nodes) | Complex network (many nodes/varied) |

| 8 | Symmetry | More asymmetry | More symmetry |

| 9 | Evoked response | Large evoked response with few stimuli (few trials/tests) | Smaller evoked response and need higher amount/number of stimuli (multiple trials/tests) |

| 10 | Neuroplasticity | Less | More |

| 11 | Wholeness/Oneness/Onefield concept | No (it is a projected/limited field) | Yes (spreading or permeating whole of universe/field) |

| 12 | Related to psychiatry | Less relevant | More relevant, because this QF is related to wholeness or reality or one consciousness concept |

| 13 | The way to alter the network | Focus few electrode [deep brain stimulation (DBS) like electrode for Parkinson etc.] | Smaller and multiple electrodes (toothbrush like electrodes) |

| 14 | The way to alter the network using frequency | High frequency is preferred in most cases (inhibition) | Low (stimulation) and high frequency stimulation depends on clinical manifestations |

| Brain function | Combination of EMF and QF (two brain fields/energy) | ||

| A | Brain function (motor, sensory, vision, sound, touch) and its impairment | Non-cognitive impairment such as stroke affecting motor, sensory, vision, sound, touch EMF is more affected than QF Measureable Associated with degree of impairment | |

| B | Brain function (language, emotion, memory, attention, planning etc.) and its impairment | Cognitive impairment for language, emotion, memory, attention, planning etc. QF is affected significantly together with EMF Measureable Associated with degree of impairment | |

| C | Brain function and psychosis | Psychotic manifestations such as auditory or visual hallucination, thought insertion, delusions etc. QF is more affected than EMF Yes or No (presence or not) (not associated with degree) | |

The two aforementioned concepts (i.e. projected stimuli or internally arising stimuli for EMF and brain as part of one consciousness) unintentionally introduce a ‘limited’ principle for both our universe and brain. For our universe, the projected stimuli is a limited stimuli from only certain aspect, area or dimension of our universe; and for the brain, the limited principle is applied for the consciousness—our brain is part of one consciousness or has limited consciousness. With these ‘limitation principle of our universe and brain’, our brain (3D-vision) cannot see wave function of a particle or atom, we can only see them in particle, atom, molecule, matter or object form. In other words, we may say partial consciousness that we have, collapsing the wave function of a particle and thus limited our perception to only three-dimensional vision (particle, atom, molecule, matter).