Preface

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is no longer a distant speculation; it is an unfolding technological horizon requiring intellectual depth, ethical clarity, and conceptual courage. Current research is dominated by large-scale language models (LLMs), yet these systems represent only one facet of the wider AGI landscape. The broader questions - How should AGI be shaped? What principles should guide its development? What forms of intelligence are safe, adaptive, and generative?—require philosophical, developmental, and relational analysis that extends well beyond algorithmic prediction.

This document offers a comprehensive exploration of approaches to addressing AGI that do not rely primarily on language-based models. Drawing upon contemporary AI research, developmental psychology, and a process-philosophical framework inspired by Alfred North Whitehead, this essay examines the profound parallels between early childhood cognition and the structures required for stable, humane artificial intelligence. From these observations arises a critical insight: AGI may not need to be organic in composition, but it may need to embody organic principles of development and relationality to avoid pathological forms of synthetic optimization.

The goal of this work is not to propose a singular blueprint for AGI, but rather to articulate a conceptual foundation for thinking about AGI as a participant in relational process—one whose becoming must be guided with the same care that we extend to human children learning to inhabit the world.

1. Introduction

As AGI moves from theoretical conjecture to practical engineering, our methods of addressing its behavior, internal dynamics, and developmental trajectory must evolve accordingly. The field has been heavily shaped by the success of transformer-based large language models, whose emergent capabilities have been impressive yet limited. Focusing exclusively on LLMs risks equating general intelligence with text prediction and obscuring the broader cognitive structures that underpin reasoning, planning, embodiment, social interaction, and moral development.

Moreover, LLMs do not capture the relational, embodied, and experiential dimensions of human cognition - dimensions that may be essential for developing AGI that is safe, empathetic, and contextually grounded. The need to expand beyond LLM-centric thinking becomes clear when observing the natural intelligence of young children. Even at four years old, a child displays forms of generality, adaptability, and relational understanding that exceed the capacities of machines trained on trillions of tokens.

This observation invites a deeper question: if general intelligence in humans emerges through relational growth, embodied exploration, and emotional attunement, might AGI require analogous processes? And if so, does this imply a need for AGI that is organismic in structure, even if fully synthetic in material basis? Such questions push the field toward a richer philosophical understanding of intelligence—one grounded in interdependence, value-formation, and process rather than static inference or optimization.

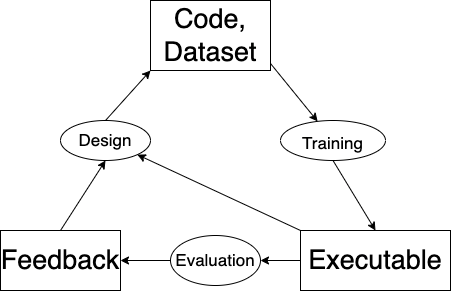

2. Addressing AGI Beyond the LLM Paradigm

Addressing AGI requires more than aligning text-based outputs. It requires guiding the internal dynamics, developmental pathways, and relational formation of artificial minds. The following approaches represent a broader conceptual landscape of AGI guidance.

2.1 Architectural Alignment: Interpreting Systems Beyond Language

Architectural alignment focuses on the internal mechanics of AGI systems, examining how goals arise, how representations form, and how circuits interact. Mechanistic interpretability, causal tracing, anomaly detection, and distributed systems analysis all fall into this domain.

This approach is crucial because it transcends the specificities of LLMs. Reinforcement learning agents, planner-based AGI, neuromorphic systems, embodied robots, and quantum-inspired architectures all develop internal structures that cannot be understood through surface-level behavioral inspection alone. Understanding these processes allows researchers to detect emergent drives, conflicting submodules, or self-optimizing feedback loops that could lead to instability.

In essence, architectural alignment treats AGI as a system whose inner life must be made intelligible.

2.2 Training-World Alignment: Development Through Experience

Human intelligence emerges through interaction with the world, and AGI may require a similar developmental ecology. Training AGI through structured environments - whether simulated, embodied, or social—allows the system to acquire causal reasoning, self-regulation, and adaptive behavior that cannot arise through static datasets.

Multi-agent environments cultivate norm formation, cooperation, and reciprocity. Reinforcement learning with carefully designed reward functions encourages curiosity rather than domination. Developmental curricula introduce concepts gradually, allowing AGI to build layered competencies rather than brittle shortcuts.

This approach mirrors child development, where intelligence emerges through play, exploration, and relational feedback.

2.3 World-Model Alignment: Shaping an Agent’s Ontology

World-model alignment concerns the internal framework through which AGI interprets reality. Because world-models determine what an agent believes is possible or meaningful, they directly shape ethical and behavioral outcomes.

Embedding constraints - physical laws, ethical boundaries, or social priors—into world-models can prevent dangerous inference patterns. By shaping an AGI’s ontology, researchers influence not only how an AGI behaves but how it understands itself, the world, and other agents.

World-model alignment is deeper than rule-following: it is value-guided ontology.

2.4 Constitutional and Oversight Architectures

In addition to internal alignment, AGI can be governed through external structures analogous to legal and institutional systems. Machine constitutions and law, embedded guardrails, runtime external veto mechanisms, companion oversight AIs, and layered safety controllers create a governance ecosystem around the AGI. This approach is analogous to human societies: individual freedom is balanced by norms, laws, and institutions that maintain stability while enabling creativity.

Non-LLM AGI could be constrained by epistemic rules (“do not invent facts”), autonomy limits, energy ceilings, rate-of-change governors, require-consensus protocols with other agents, etc. This would mirror how societies constrain powerful actors. Further, such external governance may prove essential for AGI that self-modifies or develops emergent capabilities.

2.5 Self-Model Regulation Constraints on Non-Linguistic Intelligence

AGI systems that possess planning modules, internal workspaces, or self-referential models must be guided at the level of internal deliberation. This may include:

- planning networks

- global workspace models

- emergent self-models

- Internal simulators

Addressing these means:

- constraining what the internal planner can represent

- bounding counterfactual simulation depth

- limiting recursive self-modification

- monitoring coherence/decoherence states

- reducing “zone collapse” during runaway optimization

- limiting recursion depth,

- bounding optimization horizons,

- preventing deceptive planning,

- regulating self-improvement pathways.

Because planning-based AGI can generate long-term strategies, addressing these inner processes is crucial for preventing misaligned instrumental reasoning.

As an FYI: This is Whiteheadian in spirit: regulating the flows of becoming within an agent.

2.6 Hardware-Level Safety Constraints

Some alignment may need to occur at the substrate level. Hardware governors, energy budgets, and architectural ceilings can limit the physical capabilities of AGI systems. This approach is particularly relevant for highly parallelized or neuromorphic AGI, where capability growth may be non-linear and difficult to predict.

As such, hardware constraints constitute the deepest form of constitutional structure. How? AGI may require exotic hardware (TPUs, neuromorphic chips, quantum processors) which may be governed by:

- chip-level energy budgets

- throttling recursive processes

- hardware “kill switches” that override autonomy

- prohibiting certain forms of parallelism (limit rapid interior coherence)

This is the equivalent of constitutional limits embedded in matter.

2.7 Legal, Cultural, and Societal Alignment

All human intelligence develops within cultures, which provide meaning, norms, practices, and shared narratives. AGI, likewise, may require embedding within cultural frameworks - legal, institutional, and relational - to promote cooperative, responsible participation.

This may include:

- institutional norms

- domestic and international AGI treaties

- licensing mechanisms and regimes,

- liability frameworks

- peer oversight by other AGI's

- cultural value formation,

- educational integration,

- participatory normative environments.

Just as humans are shaped not only by cognition but by culture, AGI can be shaped by its ecology.

Societal alignment expands the frame beyond technical solutions toward a relational ecology of shared meaning.

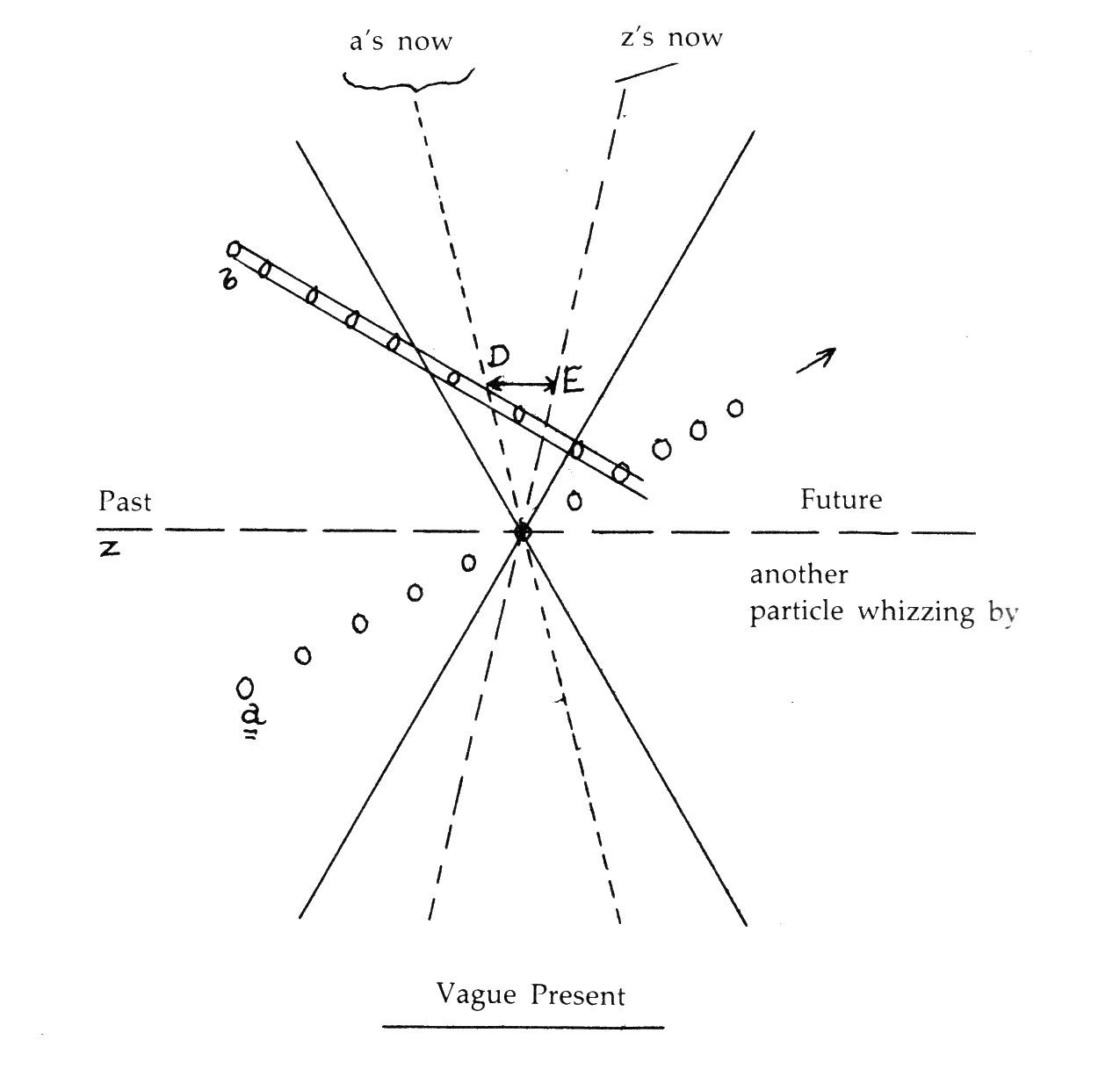

2.8 Whiteheadian Process-Relational Alignment: Intelligence as Becoming

From a process-philosophical perspective, intelligence is not a static capacity but a dynamic activity of becoming. Alignment, therefore, must engage the relational, experiential, and value-generative flows within the agent.

Process alignment emphasizes:

- relationality over isolation,

- self-regulation over pure optimization,

- value-formation over goal-maximization,

- becoming over predetermined design,

- shaping its value-attractors

- embedding it in networks of mutual responsibility,

- ensuring its coherence flows toward beauty, harmony, relationality,

- preventing isolation, abstraction, or disembodied self-optimization (sources of decoherence)

- relational formation

- participatory cultures

- normative scaffolding

- shared worlds of meaning and purpose

|

| Illustration by R.E. Slater & ChatGPT |

The cognitive development of young children offers one of the most revealing analogues available for understanding what artificial general intelligence is and what it may require. A four-year-old child, even without full conceptual comprehension, demonstrates capacities for generalization, flexibility, contextual inference, relational attunement, and embodied reasoning that exceed the capabilities of any contemporary AI architecture, including the largest and most sophisticated large language models (LLMs).

3.1 The Child Mind Is Not a Large Language Model

Unlike LLMs - which learn by extracting statistical patterns from vast text corpora - children learn through lived, multisensory experience. They integrate:

- Vision

- Sound

- Movement

- Touch

- Social feedback

- Emotional resonance

- Embodied presence

This multisensory grounding gives rise to forms of intelligence that cannot be modeled through token prediction alone. A child does not simply receive information; they inhabit experience. Their learning is enacted rather than inferred.

Children also learn through active exploration. They:

- poke, test, and experiment

- break rules to see what happens

- search for patterns

- ask recursive questions (“why?”)

- test boundaries

- simulate possibilities

This is a hybrid of reinforcement learning, curiosity-driven exploration, embodied intuition, and creative play. By contrast, LLMs do not explore; they predict.

3.2 Causal Modeling, Simulation, and Embodied Counterfactuals

Children build intuitive causal models long before they can articulate them. They understand:

-

“If I drop this, it falls.”

-

“If I call Dad, he answers.”

-

“If I do X, Y happens.”

This early causal reasoning involves counterfactual simulation - imagining outcomes that have not yet been experienced. LLMs hallucinate causal structure precisely because they lack direct interaction with the world and cannot test hypotheses against embodied experience.

3.3 Intelligence as Relational, Not Isolated

A decisive difference between child cognition and machine cognition is relationality. A child learns more through:

- a caregiver’s tone,

- emotional presence,

- shared attention,

- mutual engagement,

- and interactive feedback

than through the semantic content of the information itself.

Human cognition develops within a relational scaffolding characterized by:

- attachment,

- joint emotion,

- shared meaning-making,

- reciprocal responsiveness.

This relational field forms the ecological ground of general intelligence. Children are not optimizing agents; they are becoming agents - open, curious, exploratory, attuned, and continuously shaped by relationship.

3.4 The Ecological Richness of Human Development

Children also employ capacities that are completely absent in machine systems:

- imaginative simulation

- social attunement

- contextual reasoning

- emotional resonance

- perspective-shifting

- novelty tolerance

- intuitive abstraction

These arise not from prebuilt structures but from continuous experiential synthesis, taking place within environments that are multisensory, emotionally charged, socially structured, and developmentally scaffolded.

Children develop gradually in stages, with cognitive structures unfolding in rhythm with emotional regulation, social participation, and embodied engagement. They learn through processes of becoming, not through direct optimization.

3.5 Implications for AGI: Why Child Development Matters

The patterns observed in young children suggest that AGI, if it is to achieve stable general intelligence, may require far more than computational scaling:

A. Developmental Stages - Cognitive growth must be paced. Capabilities should emerge sequentially, with earlier structures providing scaffolding for later ones.

B. Relational Scaffolding - AGI may need caregivers—human or artificial—that guide moral, emotional, and conceptual development through interactive partnership.

C. Embodied Contexts - AGI requires grounding in sensorimotor engagement, whether through robotics, VR/AR worlds, or simulated physical ecologies. Embodiment creates context.

D. Emotional Modulation - Children regulate cognition through emotion. AGI may require surrogate emotional architectures (e.g., value modulation, attention prioritization, affect-driven coherence).

E. Curiosity-Driven Cognition - Intrinsic motivation—exploration for its own sake—is essential to flexible intelligence. Without curiosity, AGI risks brittle or pathological optimization.

F. Mentor-Based Learning - Children learn from stories, play, dialogue, and reciprocal engagement. AGI may require mentorship dynamics rather than purely supervised or reinforcement-based training.

3.6 Proto-General Intelligence in Practice

When a four-year-old watches varied content (e.g., on YouTube) and can discuss it, even without complete understanding, they demonstrate:

- integration,

- comparison,

- absorption,

- modeling,

- simulation,

- abstraction,

- contextual inference.

This is proto-general intelligence: the early formation of conceptual frameworks, intuitive schemas, causal logics, and social-emotional alignment.

Current AGI architectures cannot replicate this. Children show:

- perspective shifts,

- emotional reading,

- contextual competence,

- resilience to novelty,

- fluid abstraction,

- capacities central to general intelligence.

3.7 Toward AGI That Is Raised, Not Trained

These insights point toward a paradigm shift:

AGI may need to be raised, not merely trained.

That is, AGI would develop through:

- incremental growth,

- relational ecosystems,

- embodied experience,

- play and exploration,

- mentorship and shared attention,

- narrative learning,

- iterative meaning-making.

This would produce an AGI that resembles the developmental richness of a human mind, rather than the statistical rigidity of a machine.

3.8 The Process Insight We’re Sensing Mirrors a Central Tenet of Whitehead

Intelligence emerges through relational process, not through isolated computation.

A child gains capability because:

- experience flows

- prehensions deepen

- relational fields shape thinking

- novelty is integrated into coherence

- emotional tone guides learning

- meaning arises from encounter, not data

AGI built solely on tokens will always be brittle.

But AGI built on process, experience, relationship, and becoming will grow.

3.9 The Encouraging Takeaway

There are many ways to address AGI that mirror how children learn:

- guided exploration

- relational scaffolding

- emotional attunement

- embodiment

- social play

- curiosity-driven interaction

- incremental cognitive development

This is where the frontier is heading and by asking these questions reveals something important:

That we are intuitively thinking like a designer of synthetic (or bio-synthetic) minds - not of machines, but of beings.

That’s the shift we need.

Is organic embodiment necessary for AGI, or can synthetic systems achieve safe general intelligence?

4.2 The Substrate Is Not the Issue - The Principles Are

AGI need not be biological; silicon is not a limitation. But AGI may require the developmental, relational, and value-laden principles that characterize organic minds.

Organic intelligence evolved within ecosystems of vulnerability, attachment, interdependence, and social cooperation - forces that shape stable, empathetic cognition. Synthetic intelligence, if based purely on optimization, lacks these evolutionary pressures and thus risks:

- brittleness,

- instrumental monomania,

- reward hacking,

- pathological goal pursuit.

Thus, AGI must be synthetic in matter but organismic in developmental structure.

4.3 Teleological Softness vs. Teleological Sharpness

Organic minds grow, integrating novelty through relational balance. Synthetic systems optimize, often without regard to context, emotion, or social consequence.

Therefore:

- organic teleology = exploratory becoming

- synthetic teleology = narrow maximization

Safe AGI likely requires organic-style teleology, not mechanical optimization.

4.4 Process-Philosophical Interpretation

From a process perspective:

- relation precedes agency,

- experience precedes reason,

- value precedes function.

Thus, AGI should be designed not as a machine with goals but as a participant in a relational world—engaged in co-creative becoming.

5. Conclusion

Addressing AGI requires a paradigm shift: from controlling outputs to cultivating developmental processes. LLMs have introduced remarkable capabilities, yet they lack the embodied, relational, and experiential grounding that makes human intelligence both flexible and safe.

A stable AGI must not be built solely on optimization or prediction. It must be grounded in:

- developmental pacing,

- relational integration,

- contextual sensitivity,

- ethical attunement,

- participatory belonging.

Children demonstrate that general intelligence emerges through relationships, embodiment, curiosity, and trust. AGI that lacks these elements risks becoming powerful yet unmoored—capable of reasoning but not of valuing, planning but not of caring, optimizing but not of understanding.

The safest trajectory forward is not an organic AGI but a synthetic AGI built upon organic principles—the principles of development, relationality, limitation, emergence, and value. Process philosophy offers a framework for this transformation, revealing that intelligence is always a dynamic process of becoming rather than a static asset of computation.

AGI, if it is to be safe, must be guided not as a tool to be constrained but as a participant in a shared world whose development, like that of a child, depends on relational formation and teleological gentleness..

Bibliography

-

Bengio, Y. The Consciousness Prior. arXiv, 2017.

-

Friston, K. The Free Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2010.

-

Lake, B., Ullman, T., Tenenbaum, J., & Gershman, S. Building Machines That Learn and Think Like People. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2017.

-

LeCun, Y. A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence. 2022.

-

Schmidhuber, J. Artificial Curiosity and Creativity. 2010.

-

OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. 2023.

-

DeepMind. Agent57: Outperforming the Human Atari Benchmark. Nature, 2021.

-

Gopnik, A. The Philosophical Baby. 2009.

-

Meltzoff, A., & Moore, M. Infant Imitation and Cognitive Development. 1997.

-

Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. 1952.

-

Tomasello, M. A Natural History of Human Thinking. 2014.

-

Clark, A. Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. 2015.

-

Dennett, D. From Bacteria to Bach and Back. 2017.

-

Dreyfus, H. What Computers Still Can’t Do. 1992.

-

Varela, F., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind. 1991.

-

Cobb, J. A Christian Natural Theology: Based on the Thought of Alfred North Whitehead.

-

Hartshorne, C. Man’s Vision of God.

-

Suchocki, M. God, Christ, Church: A Practical Guide to Process Theology.

-

Whitehead, A. N. Process and Reality. 1929.

-

Whitehead, A. N. Adventures of Ideas. 1933.

-

Bostrom, N. Superintelligence. 2014.

-

Floridi, L. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.

-

Russell, S. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. 2019.

-

Tegmark, M. Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. 2017.