Introduction

From the ancient temples of Greece to the digital theologies of today, Western thought has passed through profound and often paradoxical transitions. Each era - the classical, the medieval, the modern - bears its own metaphysical signature, theological orientation, and cultural imprint. What has often gone unnoticed, however, is the thread of processual thought - a deep metaphysical concern with becoming, relation, novelty, and lived experience - that pulses beneath the dominant paradigms of each age.

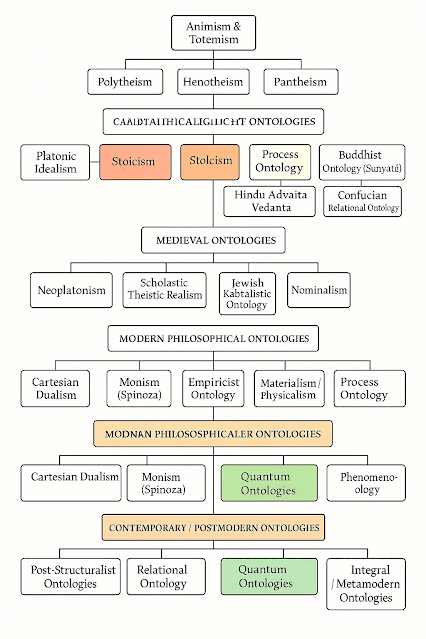

This exposé follows that thread. It offers a panoramic view of how philosophical metaphysics and theological ideas co-evolved across twelve historical epochs. From Plato’s ideal forms to Aquinas’s scholastic hierarchies, from the Enlightenment’s mechanistic rationalism to the postmodern critique of truth, and finally into the reconstructive ethos of metamodernism and Whiteheadian process philosophy - each moment offers insight into how the West has thought about reality, divinity, and meaning.

By aligning each epoch’s dominant metaphysical vision with its theological commitments, and then interpreting them through the lens of Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy, we illuminate not just a history of ideas, but a living map of transformation. Processualism helps us see how truth evolves, how theology can be dynamic and relational, and how new integrations are possible beyond binaries of faith and reason, form and flow, or past and future.

Ib Scholasticism

Ic Renaissance

Id Reformation

---

III Romanticism

IV Victorianism/Realism

V Modernism

VI Postmodernism

VII Metamodernism

VIII Processualism

|

Table by R.E. Slater & ChatGPT |

I. Classicism (Greece & Rome | ~500 BCE – 500 CE)

1. Historical Context:

City-states, Roman Republic and Empire, early science, mythos-to-logos transition

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Plato (ideal forms), Aristotle (substance, telos), Stoicism (logos), Epicureanism (atoms & void)

3. Theological Expression:

Polytheism, fate, virtue; early development of natural theology

4. Cultural Output:

Tragedy, epics (Homer, Virgil), sculpture, architecture (Parthenon, Coliseum)

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Whitehead draws heavily on Plato’s eternal objects but critiques substance metaphysics; admires aesthetic form

6. Processual Threads:

Emphasis on cosmic order (logos) and eternal becoming in early thought, later eclipsed by static form and hierarchy

Ia. Late Antiquity & Early Christianity (~100 – 600 CE)

As Rome declined, Christianity rose, reshaping the classical worldview into one dominated by theological absolutes. Neoplatonism provided a dualistic framework - dividing the eternal and temporal - that shaped Christian doctrines of God’s immutability and the soul’s separation from the body. Church councils formalized creeds that anchored divine truth in unchanging metaphysical propositions.

Processually, while the early Jesus movement emphasized relationality and divine nearness, institutional theology largely suppressed these processual intuitions in favor of static orthodoxy and divine transcendence.

1. Historical Context:

Fall of Rome, Christianization of Empire, doctrinal councils (Nicea, Chalcedon)

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Neoplatonism (Plotinus), dualism, synthesis of classical and Christian thought

3. Theological Expression:

Trinitarian dogma, soul-body dualism, eternal immutability of God

4. Cultural Output:

Monasticism, creeds, icons, liturgies, Augustine’s Confessions and City of God

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Critiques timeless divine immutability; sees this as the moment when process was eclipsed by fixed metaphysical absolutism

6. Processual Threads:

Suppressed: dynamic relationality of early Christian experience buried beneath static metaphysical scaffolding

Ib. Medieval Scholasticism (~600 – 1300 CE)

In the Middle Ages, reason was harnessed to serve theology through scholastic synthesis, especially via Thomas Aquinas’s integration of Aristotle with Christian doctrine. God became the first cause in a chain of rational necessity. Universities emerged, shaping metaphysics into a structured, hierarchical system of knowledge. The eternal, the unmoved, and the perfectly complete were idealized.

For process thinkers, this era represents the height of abstraction and over-rationalization - turning dynamic theological experiences into rigid frameworks of divine logic.

1. Historical Context:

Rise of feudalism, Islamic and Jewish philosophical transmission, cathedral schools → universities

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Aristotelianism revived via Aquinas; rationality dominates theology

3. Theological Expression:

Divine hierarchy, natural law, emphasis on logic and divine simplicity

4. Cultural Output:

Summa Theologica, Gothic cathedrals, scholastic disputations

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Commends intellectual rigor but critiques fixation on substance and final cause over relational dynamism

6. Processual Threads:

Dormant beneath Aristotelian logic and cosmic hierarchy

Ic. Renaissance (~1300 – 1600 CE)

The Renaissance marked a rebirth of classical sources, but with a renewed emphasis on human creativity, individuality, and embodied experience. Humanism placed value on beauty, freedom, and expression, reinvigorating arts, literature, and early scientific curiosity. Mystical voices and reformers began to challenge ecclesial authority, foreshadowing theological shifts to come.

From a processual perspective, this era recovered the aesthetic and experiential dimensions of existence, setting the stage for more relational and participatory metaphysical inquiries.

1. Historical Context:

Rediscovery of classical texts, humanism, printing press, early scientific curiosity

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Humanism, individual dignity, early skepticism, arts as insight into nature

3. Theological Expression:

Mysticism, reformist voices (Erasmus), challenges to church authority

4. Cultural Output:

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Shakespeare, Cervantes

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Renaissance recovers aesthetic and experiential value, preluding process aesthetics

6. Processual Threads:

Emerging: creativity, becoming, and human participation in a dynamic cosmos

Id. The Protestant Reformation (~1517 – 1650)

The Reformation shattered the religious unity of Christendom. Centering spiritual authority in the individual’s conscience and Scripture, reformers like Luther and Calvin emphasized grace, history, and personal encounter with God. While it decentralized theological power and revived the importance of lived faith, it also introduced rigid dogmatic systems (like Calvinist predestination) that often froze processual openness. Nonetheless, the Reformation reawakened the historical and relational elements of faith that process thought would later embrace.

1. Historical Context:

Luther, Calvin, Zwingli; Protestant-Catholic schisms; wars of religion

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Conscience, grace, anti-hierarchy, individual scripture interpretation

3. Theological Expression:

Sola scriptura, justification by faith, predestination, spiritual priesthood

4. Cultural Output:

Vernacular Bibles, iconoclasm, confessions of faith, martyr narratives

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Appreciates the return to historical becoming and ethical agency, though rigid predestination is rejected

6. Processual Threads:

Partially revived: emphasis on experience, history, and conscience; partially suppressed via deterministic theology

II. Enlightenment (1600 – 1800)

This epoch exalted reason, science, and individual liberty. Thinkers like Descartes, Newton, and Kant pursued universal laws and objective truths, envisioning the universe as a vast machine governed by rational principles. Religion was reframed as natural theology or deism - God as cosmic watchmaker. Although it advanced science and human rights, the Enlightenment severed facts from values, reason from emotion, and subject from object.

Whitehead critiqued this bifurcation, arguing for a metaphysic where facts, values, and experience co-evolve in creative relation.

1. Historical Context:

Scientific revolution, reason, rise of secularism, American and French Revolutions

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Rationalism (Descartes), empiricism (Locke), Kantian synthesis

3. Theological Expression:

Deism, natural religion, moral theism, rejection of miracles

4. Cultural Output:

Newtonian physics, encyclopedias, classical music, political liberalism

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Whitehead critiques the mechanistic and bifurcated view of nature: mind vs. matter, fact vs. value

6. Processual Threads:

Suppressed: cosmos seen as clockwork; relation, emotion, and creativity subordinated to reason

III. Romanticism (~1780 – 1850)

Romanticism reacted against Enlightenment coldness with passion, imagination, and a reverence for nature. It emphasized subjective experience, the sublime, and the deep emotional life of the individual. Poets, composers, and philosophers embraced intuition, longing, and organic connection. Pantheism (not panentheism) and mystical spirituality flourished.

Process thinkers see Romanticism as a partial return to the felt texture of life and cosmic interrelation - though often without the metaphysical rigor to ground its vision as provided in process philosophy.

1. Historical Context:

Industrial revolution, French Revolution aftermath, urbanization

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Imagination, nature as living whole, subjectivity, German idealism (Schelling, Fichte)

3. Theological Expression:

Pantheism, mystical theology, divine immanence, early existential faith

4. Cultural Output:

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, Mary Shelley, Beethoven, Delacroix

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Romanticism recovers experiential depth and creative subjectivity; aligns with process aesthetics, but lacks rigorous metaphysics

6. Processual Threads:

Revived: Emotion, nature, aesthetic becoming, and organic wholeness re-enter philosophy and theology

IV. Victorianism & Realism (~1830 – 1900)

A period of industrial expansion and moral reform, Victorianism valued order, discipline, and social responsibility. Realist literature depicted the struggles of everyday life, while scientific materialism and historical criticism challenged traditional beliefs. Theologians grappled with reconciling faith and evolution.

From a processual standpoint, this era offered rich ethical insight but lacked metaphysical imagination - often moralizing experience instead of opening it to novelty and transformation.

1. Historical Context:

Industrialism, empire, social reform, urban poverty, evolution

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Utilitarianism (Mill), positivism, social Darwinism, historical criticism

3. Theological Expression:

Moral Protestantism, social gospel, higher criticism of Scripture, crisis of faith

4. Cultural Output:

Dickens, Eliot, Tolstoy, Flaubert, realist painting and early photography

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Values social concern but critiques loss of creativity and aesthetic transcendence

6. Processual Threads:

Undervalued: Rational order and moralism dominate over becoming and novelty

V. Modernism (~1890 – 1945)

Modernism emerged out of disillusionment with traditional structures after WWI. It broke aesthetic and philosophical conventions, exploring fragmentation, alienation, and inner consciousness. Theologically, this was the era of crisis and silence - God as absent or unknowable.

But it was also the era of William James, Bergson, and Whitehead, who introduced metaphysical frameworks for subjectivity, creativity, and time. Modernism’s broken forms found coherence in process thought, which honored flux while reimagining divine presence.

1. Historical Context:

WWI, fragmentation of empire, urban alienation, technological upheaval

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Existentialism, pragmatism, Freudian psychoanalysis, Bergson’s duration

3. Theological Expression:

Neo-orthodoxy (Barth), crisis theology, God of absence or silence

4. Cultural Output:

Joyce, Woolf, Kafka, Picasso, Eliot, early cinema, stream of consciousness

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Whitehead provides a rigorous metaphysical ground for modernist themes: relationality, becoming, novelty, and aesthetic coherence

6. Processual Threads:

Revived and deepened: Creativity, interiority, history, aesthetics as metaphysical foundations

VI. Postmodernism (~1950 – 1990s)

Postmodernism deconstructed the very possibility of universal truth, grand narratives, or fixed identities. It reveled in irony, pastiche, and pluralism, challenging claims to authority and coherence. Theologically, it gave rise to liberation, feminist, and postcolonial theologies.

While process thinkers appreciate its critique of totalizing systems, they diverge by affirming the possibility of relational coherence - not as fixed certainty, but as evolving harmony grounded in creative advance.

1. Historical Context:

Cold War, consumerism, digital age, post-colonialism

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Deconstruction (Derrida), power/knowledge (Foucault), skepticism of metanarratives (Lyotard)

3. Theological Expression:

Death of God theology, liberation theologies, feminist/postcolonial theologies

4. Cultural Output:

Pynchon, Borges, Warhol, meta-art, media simulation, irony and pastiche

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Affirms critique of authoritarian structures but insists on coherence, creativity, and ethical becoming

6. Processual Threads:

Critically fragmented: Becomes hyper-aware of difference and construction, but risks nihilism

VII. Metamodernism (~2000s – present)

This era moves beyond postmodern cynicism by oscillating between irony and sincerity, faith and doubt, construction and care. It seeks integration without naiveté - reviving hope, depth, and purpose without denying complexity.

Process theology thrives in this mood, offering a metaphysical architecture that honors plurality, relation, and spiritual becoming in an open world. Whiteheadian thought becomes a backbone for those seeking meaning in motion.

1. Historical Context:

Climate change, digital interconnectedness, political polarization, pandemic trauma

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Oscillation between hope and doubt, sincerity and irony, pragmatic pluralism

3. Theological Expression:

Open and relational theology, planetary spirituality, pluralist participation

4. Cultural Output:

David Foster Wallace, Greta Gerwig, Bo Burnham, Everything Everywhere All at Once

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Process thought resurfaces as ideal metamodern metaphysical core: fluid, participatory, relational, aesthetic, and ethical

6. Processual Threads:

Actively revived: Meaning is re-sought through sincerity, pluralism, and co-creative becoming

VIII. Processualism (Whitehead → Present)

Rooted in Whitehead’s Process and Reality, this emergent metaphysical movement redefines reality as relational, dynamic, and co-creative. It sees all entities - including God - not as fixed substances, but as evolving events in a web of interconnection. Theology becomes a participatory practice, art a process of becoming, science a discovery of pattern and novelty. Processualism does not merely interpret the past; it prepares the future for more ethical (valuative), imaginative, and life-affirming forms of meaning-making.

1. Historical Context:

Anthropocene, AI consciousness, quantum physics, spiritual pluralism

2. Philosophical Worldview:

Process-relational ontology, panpsychism, indeterminacy, internal relations

3. Theological Expression:

Process theology, panentheism, Christ as cosmic lure, God as persuasive love

4. Cultural Output:

Center for Process Studies, feminist process thinkers, ecological movements, participatory politics

5. Whiteheadian Commentary:

Centerpiece: Whitehead’s metaphysical vision as integrative paradigm of beauty, novelty, and relational becoming

6. Processual Threads:

Fully manifested: Ethics, aesthetics, science, theology, and politics unified in creative advance

Conclusion

Toward a Processual Future: Reclaiming Relation, Creativity, and Becoming

What emerges from this survey is not a linear march of progress but an oscillating rhythm of emergence, suppression, and revival - a dance of metaphysical intuition and cultural response. At times, the cosmos is seen as harmonious and full of meaning; at other times, as fractured and ironic. Sometimes, God is near and participatory; at other times, distant or even declared dead.

And yet, running through all these permutations is a deeper impulse: the desire to locate meaning in motion, to find truth in relationship, and to reframe divinity as creativity itself. This is the heart of process philosophy. It does not reject the past but re-integrates it - offering a metaphysical framework flexible enough for science, tender enough for ethics, and spacious enough for spirituality.

In an age marked by climate crisis, cultural fragmentation, and technological acceleration, the need for a processual worldview has never been more urgent. By revisiting each epoch with fresh eyes - and processual insight - we not only understand where we've come from but begin to imagine where we might go.

This is not just a history. It is a path forward.