I've been reading through Wendell Berry's early collection of writings on land, work, life, and memory of all things broken, humorous, mended, or sad. Throughout his compositions lie the interwoven threads of redemption picking up the pieces of people's lives, humble as they are. Below is an introduction to Berry who I am only now realizing his voice as that of many other voices dissenting to their present economy of living disparate from nature, each other, and the world at large. For those of us who struggle with our own broken societies and the residual economies they produce let us take heart that we are not alone.

R.E. Slater

September 17, 2019

|

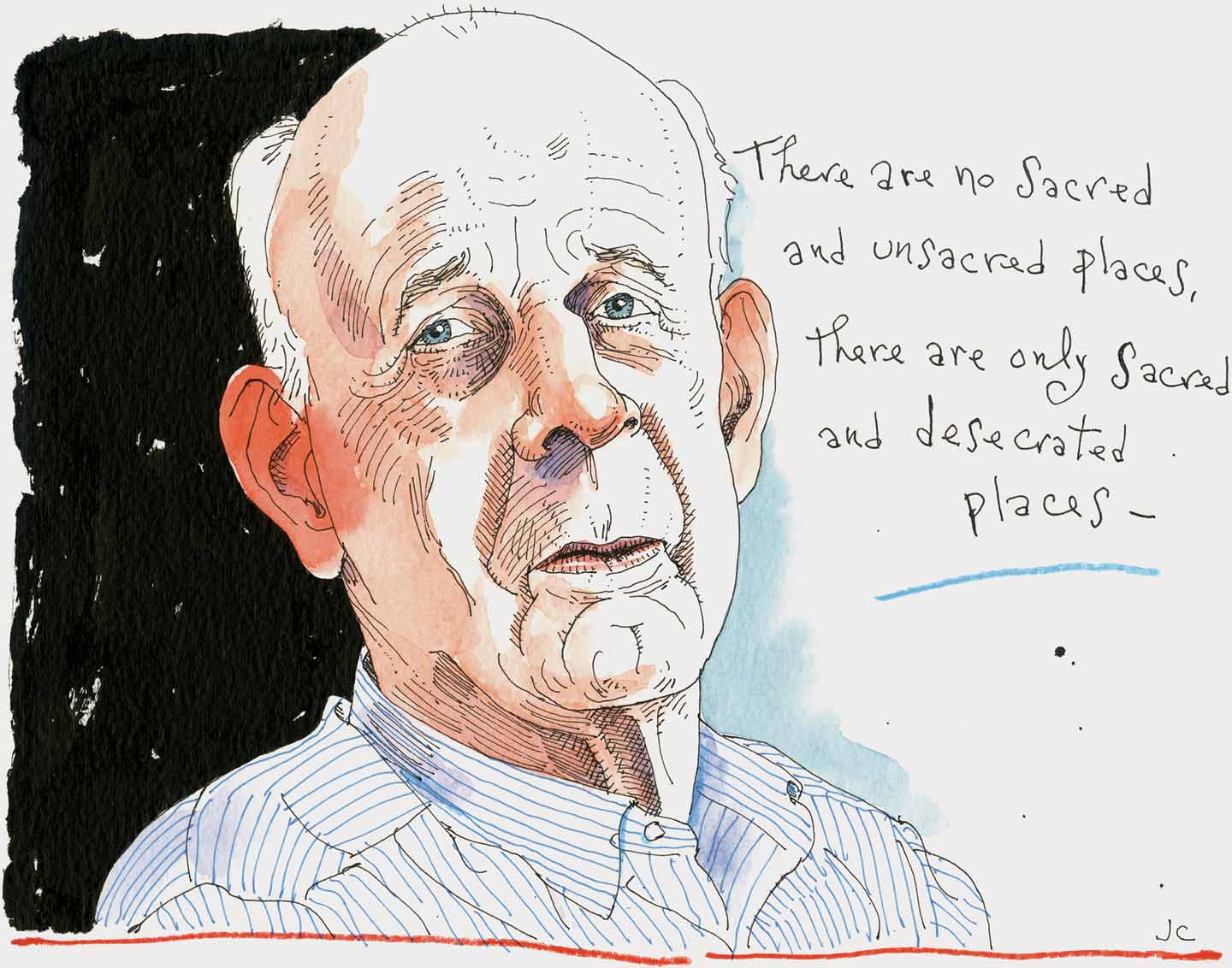

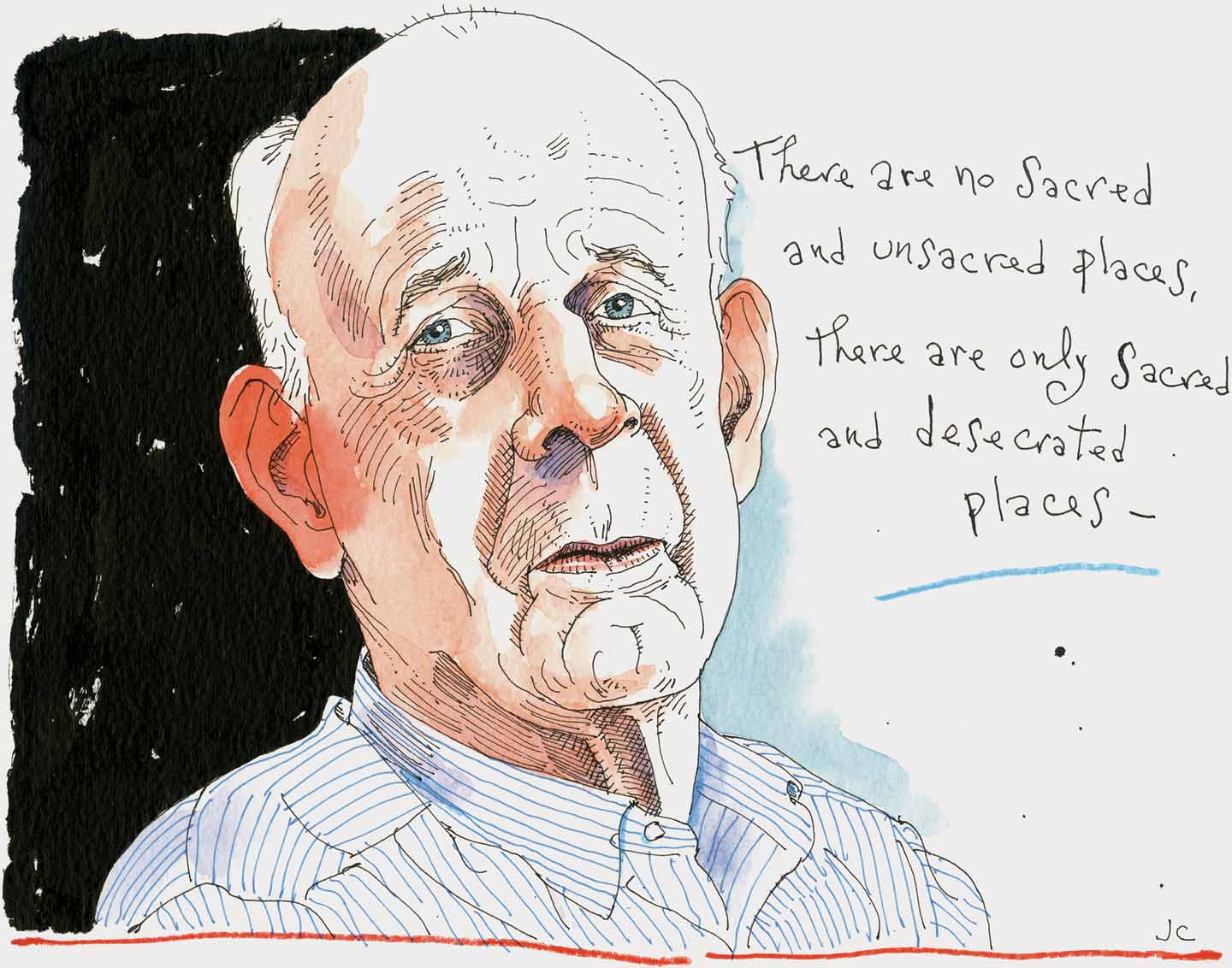

| Illustration by Joe Ciardiello |

A Shared Place:

Wendell Berry’s lifelong dissent

by Jedediah Britton-Purdy

September 9, 2019

At a time when political conflict runs deep and erects high walls, the Kentucky essayist, novelist, and poet Wendell Berry maintains an arresting mix of admirers. Barack Obama awarded him the National Humanities Medal in 2011. The following year, the socialist-feminist writer and editor Sarah Leonard published a friendly interview with him in Dissent. Yet he also gets respectful attention in the pages of The American Conservative and First Things, a right-leaning, traditionalist Christian journal.

More recently, The New Yorker ran an introduction to Berry’s thought distilled from a series of conversations, stretching over several years, with the critic Amanda Petrusich. In these conversations, Berry patiently explains why he doesn’t call himself a socialist or a conservative and recounts the mostly unchanged creed underlying his nearly six decades of writing and activism. Over the years, he has called himself an agrarian, a pacifist, and a Christian—albeit of an eccentric kind. He has written against all forms of violence and destruction—of land, communities, and human beings—and argued that the modern American way of life is a skein of violence. He is an anti-capitalist moralist and a writer of praise for what he admires: the quiet, mostly uncelebrated labor and affection that keep the world whole and might still redeem it. He is also an acerbic critic of what he dislikes, particularly modern individualism, and his emphasis on family and marriage and his ambivalence toward abortion mark him as an outsider to the left.

Berry’s writing is hard to imagine separated from his life as a farmer in a determinedly traditional style, who works the land where his family has lived for many generations using draft horses and hand labor instead of tractors and mechanical harvesters. But the life, like the ideas, crisscrosses worlds without belonging neatly to any of them. Born in 1934 in Henry County, Kentucky, Berry was but the son of a prominent local lawyer and farmer. He spent much of his childhood in the company of people from an older generation who worked the soil: his grandfather, a landowner, and the laborers who worked the family land. His early adulthood was relatively cosmopolitan. After graduating from the University of Kentucky with literary ambitions, he went to Stanford to study under the novelist Wallace Stegner at a time when Ken Kesey, Robert Stone, and Larry McMurtry were also students there. Berry went to Italy and France on a Guggenheim fellowship, then lived in New York, teaching at NYU’s Bronx campus. As he entered his 30s, he returned to Kentucky, setting up a farm in 1965 at Lane’s Landing on the Kentucky River. Although he was a member of the University of Kentucky’s faculty for nearly 20 years over two stints, ending in 1993, his identity has been indelibly that of a writer-farmer dug into his place, someone who has become nationally famous for being local, and developed the image of a timeless sage while joining, sometimes fiercely, in fights against the Vietnam War and the coal industry’s domination of his region.

Now the essays and polemics in which Berry has made his arguments clearest over the last five decades are gathered in two volumes from the Library of America, totaling 1,700 tightly set pages. Seeing his arc in one place highlights both his complexity and his consistency: The voice and preoccupations really do not change, even as the world around him does. But he is also the product of a specific historical moment, the triple disenchantment of liberal white Americans in the 1960s over the country’s racism, militarism, and ecological devastation. In the 50 years since, Berry has sifted and resifted his memory and attachment to the land, looking for resources to support an alternative America—”to affirm,” as he wrote in 1981, “my own life as a thing decent in possibility.” He has concluded that this self-affirmation is not possible in isolation or even on the scale of one’s lifetime, and he has therefore made his writing a vehicle for a reckoning with history and an ethics of social and ecological interdependence.

Berry defined his themes in the years when environmentalism grew into a mass mobilization of dissent, the civil rights movement confronted white Americans afresh with the country’s racial hierarchy and violence, and the Vietnam War joined uncritical patriotism to technocratic destruction—and stirred an anti-war movement against both. He was part of a generation in which many people confronted, as young adults, the ways that comfort and seeming safety in one place could be linked, by a thousand threads and currents, to harm elsewhere—the warm glow of electric lights to strip mining, the deed of a family farm to colonial expropriation and enslavement, the familiar sight of the Stars and Stripes to white supremacy and empire.

Such destructive interconnections became the master theme in his criticism, which portrays American life as a network of violence and exploitation, sometimes openly celebrated but more often concealed. For Berry, as for Thoreau, the work of the critic is to locate where the poisons are dumped and then turn back on oneself and ask: What is my place in all this? Is it possible to live life differently? And if so, how can I begin?

Berry’s most enduring work of nonfiction is The Unsettling of America, published in 1977. There he puts farming at the center of his critique of American life. If you want to ask how people live, he proposes, you should ask how they get their food. This is at once the most ordinary ecological exchange and the most important. It shapes everything from the land to our bodies. It is the place where the land becomes our bodies, and the other way around. And by this measure, Berry continues, American agriculture has proved a disaster. A good farm should renew its soil with diverse cropping and manure, providing fertility for the future. Instead, American farming has become a hybrid of factory production and mining. It strips the soil of its organic fertility and replaces it with synthetic fertilizers, either literally mined (phosphorus) or produced with considerable amounts of fossil fuels (nitrogen). Its waste becomes a pollutant—the manure from industrial-scale animal operations and the fertilizer runoff from corn and soybean monocrops, which poison waterways and aquifers. When farms are turned into dirt-based factories, they lose their power to absorb and store carbon and begin to contribute, like other factories, to climate change.

What does this disaster say about the people who create it? For Berry, American agriculture showed the country’s devotion to a mistaken standard of economic efficiency, which in practice tended to mean corporate profit. Both the market and the federal government confronted farmers with a stark choice: “Get big or get out,” in the words of Earl Butz, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford’s secretary of agriculture and a villain in The Unsettling of America. Success meant squeezing more and more out of the bottom line, no matter how it affected farming communities or the land. It also meant embracing a new scale and pace, with mechanical harvesters, industrial barns, and synthetic chemicals greatly reducing the need for human labor. In 1870, nearly half of American workers were farmers; in 1920, 27 percent were; today, it’s less than 1 percent. Not so long ago, working the land was the major form of life in many communities. Today, it is mostly a branch of industrial management for landowners and a grueling form of labor for seasonal and migrant workers. Far from economic progress, Berry concludes, the unsettling of America produced a cultural and ecological catastrophe. Whole forms of life, whole swaths of ecological diversity, are disappearing.

He goes even further in The Unsettling of America. The destructive transformation of land, culture, and commerce is nothing new; it is merely the latest chapter in the American story—the exploitation and elimination of settled forms of life to make room for new kinds of profit-making. Looking back to the first soldiers and colonists who drove out Native Americans, Berry writes, “These conquerors have fragmented and demolished traditional communities…. They have always said that what they destroyed was outdated, provincial, and contemptible.” The conquest never ended, only changed its targets. It has always maintained a doubly exploitative attitude, toward land as a thing to be seized and mined for profit and toward human labor as a thing to be used up and discarded.

Reviewing The Unsettling of America in The New York Times, the poet Donald Hall called Berry “a prophet of our healing, a utopian poet-legislator like William Blake.” But the poetic utopia was fading fast, and the healing had come too late. Soon Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan would establish themselves as the poet-legislators of the age. Thatcher’s claim that “there is no such thing as society” and Reagan’s praise of “an America in which people can still get rich” were the antithesis of Berry’s thought. In those decades, back-to-the-landers who followed his example in the early 1970s were giving up and returning to city jobs or slipping into a weird rural libertarianism or becoming entrepreneurs who converted agrarian counterculture into the kinds of lifestyle goods and status symbols that end up on display at Whole Foods. The environmental movement was beaten back in Appalachia in the 1970s when the coal industry defeated a campaign to end strip mining, which Berry had thrown himself into wholeheartedly. The defeat set the stage for the destruction of much of the region by mountaintop-removal mining in the decades that followed while inequality grew, young people continued to flee rural counties, and the American economy financialized and globalized on archcapitalist terms.

Since The Unsettling of America appeared, Berry has been straightforwardly and unyieldingly anti-capitalist. He shares a mood with Romantic English socialists like William Morris, who did not assume that all growth is good and who aspired to build an egalitarian future that in some ways looked back to a precapitalist past. These affinities bring many of Berry’s ideas within shouting distance of nostalgia—which, in the American South, has always been a mistake at best and more often a crime.

But the core of his work—both writing and activism—has always been after something else: a reckoning with the wrongs of history and identity. He does not want to celebrate an earlier age; instead, like Morris and his peers, Berry wants to come to terms with it in the service of a clear-eyed present and a changed future. “I am forced, against all my hopes and inclinations,” he writes in “A Native Hill,” a 1969 essay, “to regard the history of my people here as the progress of the doom of what I value most in the world: the life and health of the earth, the peacefulness of human communities and households.” Centered on a walk across a slope where Berry’s ancestors and others like them drove out the original inhabitants, the essay confronts how his people worked the land, sometimes with enslaved labor, and left behind a denuded hillside that has shed topsoil into the Kentucky and Ohio rivers. “And so here, in the place I love more than any other,” he observes, “and where I have chosen among all other places to live my life, I am more painfully divided within myself than I could be in any other place.”

From the beginning, Berry has written the land’s history alongside the history of those who have worked it or been worked on it. When he returned to Kentucky in the mid-1960s, he was already reflecting on how much of the region’s—and his family’s—history was entangled with racial domination. In 1970, he concluded that “the crisis of racial awareness” that had broken into his consciousness was “fated to be the continuing crisis of my life” and that “the reflexes of racism…are embedded in my mind as deeply at least as the language I speak.” Berry argues that the mind could not be changed by will alone but only in relation to the world whose wrongs had distorted it. A writer must respond by engaging with “the destructive forces in his history,” by admitting and addressing the fact that “my people’s errors have become the features of my country.”

Even as Berry made himself a student of the flaws of local life, he sought to refashion its patterns of community and culture into something that might repair them. For him, narrowing the horizons of one’s life is the only responsible way of living, since it is how we might actually heal old wounds, clean up our own mess, and give an honest account of ourselves. Throughout his essays, he makes this case for ecological reasons but also for moral ones. Farming on a local scale, he argues, can respond to the nuances of soil and landscape and can rebuild the fertility cycle of dirt to plant to manure to dirt. Ethics also has its limits of scale. “We are trustworthy only so far as we can see,” he insists. The patterns of care that give ethics life also require a specific space. To hold ourselves accountable, we need a palpable sense of what is sustaining us and what good or harm we are doing in return. Community depends on the sympathy and moral imagination that “thrives on contact, on tangible connection.”

Berry’s judgment that localism is an ecological and moral value links his life and activism with his thought, but over the years his localism has also fostered an anti-political streak in his thinking that recasts global and collective problems as matters of community judgment and personal ethics. He laces his writings with asides dismissing “national schemes of medical aid” and “empty laws” for environmental protection. But local activity can do only so much to stop mountaintop-removal mining or industrial-scale farming. A student of material interdependence cannot ignore that the systems driving these forms of ecological devastation are just as real as the topsoil that Berry lays down on his farm at Lane’s Landing and just as powerful as the floodwaters from the Kentucky River. Politics and collective action—often through local and federal laws—are necessary, however alienating he finds them.

Some of Berry’s wariness of politics comes from his temperament. He is chiefly a moralist and a storyteller. Although he cares intensely about the effects of the economic and political orders that he criticizes, they are not the home ground of his mind in the way a local farm and community are. His wariness regarding politics also reflects something that is easily missed on account of his agrarian persona and perennially untimely style: his debt to the New Left radicalism of the late 1960s. His writing from that time reflects the New Left idea that participatory democracy is the only real democracy. “The time is past when it was enough merely to elect our officials,” he argued in 1972 concerning the fight against strip mining. “We will have to elect them and then go and watch them and keep our hands on them, the way the coal companies do.”

Horror at the Vietnam War shaped his localism as well. In 1969, he wrote of walking on a hillside watching Air Force jets screech into the valley “perfecting deadliness” and concluded, “They do not represent anything I understand as my own or that I identify with…. I am afraid that nothing I value can withstand them. I am unable to believe that what I most hope for can be served by them.”

Berry’s emphasis on place and individual responsibility can become part of the problem in the wrong hands. Back-to-the-land ethics in the 1990s and since have often sagged into a conscious consumerism that forgets participatory politics, inflates individual choices, and offers local knowledge as a status symbol and a commodity rather than a set of traditions worth preserving to prevent even further devastation. By now, calls for individual responsibility—from one’s choice of light bulbs to the search for happiness and meaningful work—are pretty clearly distractions from the lack of political programs to provide living-wage jobs and ecological restoration. A contrarian is least essential when his dogged dissent becomes an era’s lazy common sense; Berry risks becoming, willy-nilly, the philosopher of the Whole Foods meat counter.

At the same time, Berry has never shied from participating in collective action and organized resistance. He has been arrested for protesting the construction of nuclear power plants and risked arrest protesting surface mining. In 2009, he withdrew his papers from the University of Kentucky after it accepted coal money and has devoted recent years to working with his daughter, Mary Berry, to build a center to train young farmers in local practices that might resist the corporatization of agriculture. Growing up on the edge of Appalachian activist circles, I heard of him as someone who showed up—a good citizen. But it may be that the burden of his thought is a pessimism of the global intellect, married to joy (if not exactly optimism) in local work. In Wendell Berry’s view, we are caught in a powerfully warped world, and nothing of our making is likely to save us. The beauty is the struggle or, in his case, the rhythmic and seasonal labor. Indeed, the joy of work is near the center of his thinking. Our wealth is in our activity, he argues, but it is fatuous to “do what you love.” The point instead should be to make an economy, at whatever scale is possible, whose work deserves the affection of whoever joins in it.

In this respect, his local focus is not narrow but expansive. In the work of a farm and the ties of a region, he finds the materials for a theory of political economy. Like Pope Francis in the ecological tract Laudato Si’, and also like many contemporary socialists, Berry has long argued that the moral and material meaning of an economy must be two parts of the same thing. Our political economy shapes our intimate attachments, and vice versa. The personal is political, and our hearts follow our treasure. This twinned understanding of environment and economy, of personal and public life, is part of why he can appeal both to those who believe that the American ordering of political and economic power needs fundamental reconstruction and to those who believe that the values of individualism, mobility, and self-creation have led to a cultural blind alley.

Berry’s affirmative vision of interdependence finds expression in an ideal of marriage that runs through his thinking. For him, marriage is a chosen limit, a self-bounding, that helps to support and dignify all the other limits he recommends: restraint from violence, from conquest, from unchecked acquisition or the vanity of progress. It is also an expression of an intentional community, of a deliberate bonding of souls, and he describes it as being “as good an example as we can find of the responsible use of energy” and, more fulsomely, “the sexual feast and celebration that joins [the couple] to all living things and to the fertility of the earth.” In The Unsettling of America, the ideal farmscape that Berry imagines is filled with marriages on this model.

This moralizing of the most traditional relationship, along with the emphasis on localism, is part of the reason that Berry’s writing appeals to conservatives as well as progressives. But he does not defend the traditional marriage of the 20th-century nuclear household. His ideal of a union of shared work in a shared place is at once more anachronistic and more radical than that. Repudiating the right’s understanding of marriage, he argued in 2015 that the Constitution and political decency require opening marriage to same-sex couples without qualification. Speaking from his Christian tradition, he warns his coreligionists against “condemnation by category” (which he calls “the lowest form of hatred”) and “the autoerotic pleasure of despising other members” of creation.

His ideal of marriage also extends far beyond two people. It is suggestive of his larger commitment to making things whole, to imagining a good society as a great chain of being that links people and households and the earth into a single pattern. Through this image of wholeness, Berry asks moral and ecological questions in ways that conjoin what is often held apart: What harm am I involved in? What change in life could possibly redress it?

Berry’s visions of wholeness, however, can leave too little room for the thought that not all human and nonhuman goods can come into harmony, that conflict among them can be productive and a reason to prize individuality and strangeness—say, to honor a queer marriage not just because it is a marriage but also because it is queer. His passion for wholeness draws him toward the anachronistic margins of the present—the Amish, for instance, whose self-bounded form of community he admires—and dampens his interest in the radically new versions of ecological and social life that might be emerging on other margins. His wholeness is not the only wholeness, though he sometimes writes as if it were. He is, on the one hand, reconstructing his own Christian, border-state, mainly white history as one basis for “a life decent in possibility” and, on the other hand, trying to describe the general conditions for any others to live a responsible life. When his project is candidly idiosyncratic, then others may find in it some prompting for their own reconstruction, with their own equally particular inherited materials. But when Berry generalizes too hastily from what is particularly his own, his thought, ironically, can become provincial.

When I became a writer, it was probably inevitable that I would take some kind of instruction from Wendell Berry. He was the first writer I ever met, by more than a decade. I was introduced to him at a draft horse auction in Ohio sometime before I learned to read. When I did begin to read him, I found someone who had made a life’s work out of materials I had, at that time, known my whole life. He too came from steep, eroded slopes, farmed wastefully; he too worked in hay fields and barns that left the body scratched, sore, soaked in sweat, delighted; he too admired the knowledge of old people who could make a meal of wild mushrooms, some roadside greens, and a swiftly dispatched chicken. I still carry with me many of the values that Berry praises as essential, but much of what he has evoked as a life decent in possibility is far away. At present, I live in New York City and have not dedicated my life to the fertility of the land I first knew or to any one lifelong community. I love a city of strangers, whose random sociability and surprising acts of helpfulness model a very different picture of interdependence from Berry’s.

This sense of distance from him is particularly acute when it comes to abortion. Several times over the past year, I almost abandoned this essay because of Berry’s view of it. He believes that abortion takes a life; I believe the right to it is essential to women’s autonomy and egalitarian relationships. I see it as central to the vision of humane fairness that is reproductive justice and view reproductive justice as closely linked with ecological justice. Both are about a decent way for humans to go on within the larger living world. This is my version of wholeness, but it is not Berry’s, and over the years I have struggled to reconcile his views on abortion with the parts of his work that I find indispensable. Unlike his localism or his skepticism of politics, which I do not share but seem honorable expressions of important traditions, his views on abortion pull me up short. With the stakes for women’s lives so high right now, they do so even more.

Berry’s writings on reproductive justice contain an important caveat: He does not believe abortion should be the decision of the state, and he has argued that for this reason, “there should be no law either for or against abortion.” This cannot be a complete answer, and imagining it could be is a token of his distance from modern politics. Take Medicaid and the heavily regulated private insurance industry. Must they cover abortion? May they not? The question is not avoidable, and it is political as well as personal. In answering these questions, there is no such thing as the silence of the law.

Still, Berry’s stance means that all bans on performing abortion should be rejected. This is a position that falls well to the left of anything the Supreme Court has said on the matter. Nonetheless, many readers would not remotely recognize their experience in his description of the procedure as a “tragic choice” and might mistrust his judgment on other matters because of his insistence on his opinion here.

Throughout his work, Berry likes to iron out paradoxes in favor of building a unified vision, but he is himself a bundle of paradoxes, some more generative than others. A defender of community and tradition, he has been an idiosyncratic outsider his whole life, a sharp critic of both the mainstream of power and wealth and the self-styled traditionalists of the religious and cultural right. A stylist with an air of timelessness, he is in essential ways a product of the late 1960s and early ’70s, with their blend of political radicalism and ecological holism. An advocate of the commonplace against aesthetic and academic conceits, he has led his life as a richly memorialized and deeply literary adventure. Like Thoreau, Berry invites dismissive misreading as a sentimentalist, an egotist, or a scold. Like Thoreau, he is interested in the integrity of language, the quality of experience—what are the ways that one can know a place, encounter a terrain?—and above all, the question of how much scrutiny an American life can take.

All of Berry’s essays serve as documents of the bewildering destruction in which our everyday lives involve us and as a testament to those qualities in people and traditions that resist the destruction. As the economic order becomes more harrying and abstract, a politics of place is emerging in response, much of it a genuine effort to understand the ecological and historical legacies of regions in the ways that Berry has recommended. This politics is present from Durham, North Carolina, where you can study the legacy of tobacco and slavery on the Piedmont soils and stand where locals took down a Confederate statue in a guerrilla action in 2017, to New York City, where activists have built up community land trusts for affordable housing and scientists have reconstructed the deep environmental history of the country’s most densely developed region. But few of the activists and scholars involved in this politics would think of themselves as turning away from the international or the global. They are more likely to see climate change, migration, and technology as stitching together the local and global in ways that must be part of the rebuilding and enriching of community.

The global hypercapitalism that Berry denounces has involved life—human and otherwise—in a world-historical gamble concerning the effects of indefinite growth, innovation, and competition. Most of us are not the gamblers; we are the stakes. He reminds us that this gamble repeats an old pattern of mistakes and crimes: hubris and conquest, the idea that the world is here for human convenience, and the willingness of the powerful to take as much as they can. For most of his life, Berry has written as a kind of elegist, detailing the tragic path that we have taken and recalling other paths now mostly fading. In various ways, young agrarians, socialists, and other radicals now sound his themes, denouncing extractive capitalism and calling for new and renewed ways of honoring work—our own and what the writer Alyssa Battistoni calls the “work of nature.” They also insist on the need to engage political power to shape a future, not just with local work but on national and global scales. They dare to demand what he has tended to relinquish. If these strands of resistance and reconstruction persist, even prevail, Wendell Berry’s lifelong dissent—stubborn, sometimes maddening, not quite like anything else of its era—will deserve a place in our memory.

*Jedediah Britton-PurdyJedediah Britton-Purdy teaches at Columbia Law School. His new book, This Land Is Our Land: The Struggle for a New Commonwealth, will appear this fall.