The New Testament Canon's Historical Setting

by R.E. Slater & ChatGPT5

- The Apostolic Age (c. 30–100 CE): The books of the New Testament were originally composed as individual letters, gospels, and other writings, largely in the second half of the first century. These texts were meant for specific communities and were circulated among the early churches. For instance, Paul's letters were meant for the churches he founded, but he advised they be read to other congregations as well.

- The death of the apostles: As the original apostles and eyewitnesses of Jesus began to die, the early church recognized the need for authoritative written accounts to preserve the historical tradition.

- The rise of heresy: The second century saw the rise of Gnosticism, Marcionism, and other sects, which challenged orthodox Christian teaching and even promoted their own sacred texts. The Gnostic movement, for example, promoted the idea of secret knowledge for salvation, which contrasted sharply with apostolic tradition. This spurred the orthodox church to define its own canonical boundaries.

- Roman persecution: Periodic persecution under Roman emperors like Diocletian (303–306 CE) led to the confiscation and destruction of Christian scriptures. This motivated Christians to determine which writings were essential and worth risking their lives for.

- Apostolic origin: A text was considered authoritative if it was written by an apostle or a close associate of an apostle, such as Mark (associated with Peter) or Luke (associated with Paul).

- Widespread acceptance: The book had to be widely accepted and used in the worship and teaching of Christian communities across the Roman world. By the end of the second century, most churches used the four Gospels, Acts, and Paul's epistles.

- Orthodox teaching: The content of the book had to align with the core doctrines of the faith as passed down from the apostles. Texts promoting heretical views, such as the Gospel of Thomas, were ultimately rejected.

- Consistent usage: Canonical books were used repeatedly for instruction and liturgical purposes from the earliest days of the church.

- c. 140 CE: The heretic Marcion compiled his own limited canon, which motivated orthodox Christians to define their own list in opposition.

- c. 180 CE: Irenaeus, an influential bishop, was the first to assert the exclusive use of the four gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

- c. 200 CE: The Muratorian Fragment, a partial list of canonical books from this period, shows a collection similar to our modern New Testament was already in use.

- 367 CE: Athanasius, the Bishop of Alexandria, formally listed the current 27 books of the New Testament as exclusively canonical in his Festal Letter. This is the earliest known list matching the modern canon.

- 397 CE: The Council of Carthage, supported by Augustine, affirmed Athanasius's list of 27 books. This provided a definitive list for the Western church.

The dating of the New Testament's Canonical books, many of the NT writings cluster in the late 50s–60s, especially Paul’s letters. Below is a scholarly consensus range (per critical NT studies - not traditional church dating teachings).

Pauline Epistles

1 Thessalonians: c. 49-50 CE (earliest NT writing; from Corinth)

Galatians: c. 48/49–55 CE (whether before/after Jerusalem Council per North/South Galatia theory)

1 Corinthians: c. 53–55 CE (from Ephesus)

2 Corinthians: c. 55–56 CE

Romans: c. 56-58 CE (from Corinth)

Philippians: c. 60–62 CE (prison, likely Rome)

Philemon: c. 60–62 CE (written with Philippians from Roman imprisonment)

Colossians: c. 60–62 CE (authorship disputed, often “Deutero-Pauline”)

Ephesians: c. 60–80 CE (most place it later than Paul, perhaps by disciples; considered "Deutero-Pauline)

2 Thessalonians: c. 50–52 CE if Pauline; if pseudonymous, c. 70–90 CE

Pastoral Epistles (1–2 Timothy, Titus): c. 80–100 CE (most critical scholars see them as post-Pauline, reflecting ecclesiastical church order issues)

1 Thessalonians: c. 49-50 CE (earliest NT writing; from Corinth)

Galatians: c. 48/49–55 CE (whether before/after Jerusalem Council per North/South Galatia theory)

1 Corinthians: c. 53–55 CE (from Ephesus)

2 Corinthians: c. 55–56 CE

Romans: c. 56-58 CE (from Corinth)

Philippians: c. 60–62 CE (prison, likely Rome)

Philemon: c. 60–62 CE (written with Philippians from Roman imprisonment)

Colossians: c. 60–62 CE (authorship disputed, often “Deutero-Pauline”)

Ephesians: c. 60–80 CE (most place it later than Paul, perhaps by disciples; considered "Deutero-Pauline)

2 Thessalonians: c. 50–52 CE if Pauline; if pseudonymous, c. 70–90 CE

Pastoral Epistles (1–2 Timothy, Titus): c. 80–100 CE (most critical scholars see them as post-Pauline, reflecting ecclesiastical church order issues)

Gospels & Acts

Mark: c. 65–70 CE (shortly before/after fall of Jerusalem)

Matthew: c. 80–90 CE (often linked to Antioch, building on Mark + Q + unique material)

Luke: c. 80–90 CE (part one of Luke-Acts, after Mark, sharing Q; uses similar sources to Matthew + L-material)

Acts: c. 80–90 CE (a companion to Luke, situating Paul in Roman context)

John: c. 90–100 CE (final form, with earlier sources behind it; includes layers of tradition and editing within its texts)

Mark: c. 65–70 CE (shortly before/after fall of Jerusalem)

Matthew: c. 80–90 CE (often linked to Antioch, building on Mark + Q + unique material)

Luke: c. 80–90 CE (part one of Luke-Acts, after Mark, sharing Q; uses similar sources to Matthew + L-material)

Acts: c. 80–90 CE (a companion to Luke, situating Paul in Roman context)

John: c. 90–100 CE (final form, with earlier sources behind it; includes layers of tradition and editing within its texts)

Catholic (General) Epistles

James: c. 60 (if genuinely from James of Jerusalem; more often dated c.70–90 CE . The style fits the Jewish-Christian wisdom tradition)

1 Peter: c. 70–90 CE (unlikely pre-64 CE if Petrine authorship. More likely pseudonymous possibility; persecution theme suggests post-70 CE)

Jude: c. post-70–pre-100 CE (very short, apocalyptic tone warning against false teachers; draws from the Jewish pseudepigraphaic literature of 1 Enoch 1/9 (Jude 14-15))

1 John: c. 90–100 CE (seems to be from the same community as Gospel of John)

2 & 3 John: c. 90–100 CE (same Johannine community addressing internal disputes after the fall of Jerusalem and Roman occupation)

2 Peter: c. 110–130 CE (latest NT book, almost universally considered pseudonymous)

James: c. 60 (if genuinely from James of Jerusalem; more often dated c.70–90 CE . The style fits the Jewish-Christian wisdom tradition)

1 Peter: c. 70–90 CE (unlikely pre-64 CE if Petrine authorship. More likely pseudonymous possibility; persecution theme suggests post-70 CE)

Jude: c. post-70–pre-100 CE (very short, apocalyptic tone warning against false teachers; draws from the Jewish pseudepigraphaic literature of 1 Enoch 1/9 (Jude 14-15))

1 John: c. 90–100 CE (seems to be from the same community as Gospel of John)

2 & 3 John: c. 90–100 CE (same Johannine community addressing internal disputes after the fall of Jerusalem and Roman occupation)

2 Peter: c. 110–130 CE (latest NT book, almost universally considered pseudonymous)

The Christian Apocalypse

Revelation (the Apocalypse of John): c. 95-96 CE (during Domitian’s reign; some suggest as early as 68–70 CE under Nero, but majority view is 95-96 CE)

Revelation (the Apocalypse of John): c. 95-96 CE (during Domitian’s reign; some suggest as early as 68–70 CE under Nero, but majority view is 95-96 CE)

Timeline Snapshot

50s: Earliest Paul (1 Thess, Gal, Corinthians, Romans)

60s: Prison epistles, James (possibly), Mark, Philemon/Philippians/Colossians

70s–90s: Matthew, Luke-Acts, Catholic epistles (1 Peter, Jude), deutero-Pauline letters (Eph, Col, 2 Thess, 1+2 Tim, Titus)

90s–100s: John, Johannine epistles, Revelation

100–130: Pastoral epistles: Timothy 1+2, Titus (if pseudonymous), 2 Peter

50s: Earliest Paul (1 Thess, Gal, Corinthians, Romans)

60s: Prison epistles, James (possibly), Mark, Philemon/Philippians/Colossians

70s–90s: Matthew, Luke-Acts, Catholic epistles (1 Peter, Jude), deutero-Pauline letters (Eph, Col, 2 Thess, 1+2 Tim, Titus)

90s–100s: John, Johannine epistles, Revelation

100–130: Pastoral epistles: Timothy 1+2, Titus (if pseudonymous), 2 Peter

The Deutero-Pauline Letters (“deutero” = “second” or “later”)

“Undisputed Paulines” (authentic): Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon.

“Deutero-Paulines” (disputed, likely post-Paul): Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1–2 Timothy, Titus.

(Sometimes Colossians and 2 Thessalonians are put in a “middle disputed” category because scholars are more divided on them.)Ephesians

Style and vocabulary differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

Theology more “cosmic,” with emphasis on the Church as Christ’s body.

Often seen as a “circular letter” written in Paul’s tradition, c. 70–90 CE.

Colossians

Close to Paul’s style but with more developed Christology (cosmic Christ).

Many see it as by a disciple of Paul; some argue Paul himself in prison.

Date debated: 60–62 CE (if Paul) or 70–90 CE (if post-Paul).

2 Thessalonians

Language and eschatology diverge from 1 Thessalonians.

Some see it as pseudonymous, written to address eschatological confusion.

Dated 50s CE if authentic; 70–90 CE if not.

1 Timothy

One of the Pastoral Epistles.

Strong focus on church order and false teachers.

Widely seen as post-Pauline, 80–100 CE.

2 Timothy

Another Pastoral Epistle.

Personal tone, but style and theology differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

Dated 80–100 CE.

Titus

The third of the Pastoral Epistles.

Similar concerns about church order and sound teaching.

Dated 80–100 CE

Ephesians

Style and vocabulary differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

Theology more “cosmic,” with emphasis on the Church as Christ’s body.

Often seen as a “circular letter” written in Paul’s tradition, c. 70–90 CE.

Colossians

Close to Paul’s style but with more developed Christology (cosmic Christ).

Many see it as by a disciple of Paul; some argue Paul himself in prison.

Date debated: 60–62 CE (if Paul) or 70–90 CE (if post-Paul).

2 Thessalonians

Language and eschatology diverge from 1 Thessalonians.

Some see it as pseudonymous, written to address eschatological confusion.

Dated 50s CE if authentic; 70–90 CE if not.

1 Timothy

One of the Pastoral Epistles.

Strong focus on church order and false teachers.

Widely seen as post-Pauline, 80–100 CE.

2 Timothy

Another Pastoral Epistle.

Personal tone, but style and theology differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

Dated 80–100 CE.

Titus

The third of the Pastoral Epistles.

Similar concerns about church order and sound teaching.

Dated 80–100 CE

The Pastoral Epistles (1,2 Tim, Titus)

Authorship: Traditionally attributed to Paul, but most modern scholars view them as post-Pauline (c. 80–100 CE), written by a disciple or the Pauline school. Reasons:- Vocabulary and style differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

- Strong concern for church hierarchy (bishops, elders, deacons), which reflects a later stage in church development.

- Less apocalyptic urgency; more focus on institutional stability.

Theology:- Emphasis on “sound doctrine” and protecting against false teachers.

- Shift from Paul’s eschatological focus to more church order and morality.

- Pastoral in tone: guiding younger leaders (Timothy, Titus) in shepherding communities.

- Vocabulary and style differ from Paul’s authentic letters.

- Strong concern for church hierarchy (bishops, elders, deacons), which reflects a later stage in church development.

- Less apocalyptic urgency; more focus on institutional stability.

- Emphasis on “sound doctrine” and protecting against false teachers.

- Shift from Paul’s eschatological focus to more church order and morality.

- Pastoral in tone: guiding younger leaders (Timothy, Titus) in shepherding communities.

Untangling the book of Jude

Jude (the Epistle of Jude):

Date: Most scholars place it around 70–90 CE. Some push it as late as early 2nd century, but the dominant view is post-70 but pre-100.

Content: Yes, it is short, urgent, apocalyptic in tone, warning against false teachers and urging believers to “contend for the faith.”

Sources:

Jude directly quotes 1 Enoch 1:9 (vv. 14–15).

It also alludes to the Assumption of Moses (v. 9, the dispute over Moses’ body).

Important nuance: 1 Enoch and Assumption of Moses are Jewish pseudepigrapha, not Christian writings and not part of the Hebrew canon. They circulated widely in 2nd Temple Judaism and were familiar in early Christian circles.

Relation to NT: Jude is not itself pseudepigraphic in the same sense (though some debate whether “Jude, brother of James” is authentic or a literary attribution). It draws from Jewish pseudepigrapha but was accepted into the New Testament canon fairly early.

Jude (the Epistle of Jude):

Date: Most scholars place it around 70–90 CE. Some push it as late as early 2nd century, but the dominant view is post-70 but pre-100.

Content: Yes, it is short, urgent, apocalyptic in tone, warning against false teachers and urging believers to “contend for the faith.”

Sources:

Jude directly quotes 1 Enoch 1:9 (vv. 14–15).

It also alludes to the Assumption of Moses (v. 9, the dispute over Moses’ body).

Important nuance: 1 Enoch and Assumption of Moses are Jewish pseudepigrapha, not Christian writings and not part of the Hebrew canon. They circulated widely in 2nd Temple Judaism and were familiar in early Christian circles.

Relation to NT: Jude is not itself pseudepigraphic in the same sense (though some debate whether “Jude, brother of James” is authentic or a literary attribution). It draws from Jewish pseudepigrapha but was accepted into the New Testament canon fairly early.

NT Books which Cite or Allude to the Jewish Pseudepigrapha/Apocrypha

The Apocrypha (also known as Deutero-canonical books) are Jewish writings not in the Hebrew Bible but included in the Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments (called Deuterocanonical books), while the Pseudepigrapha are a larger, even less authoritative collection of ancient Jewish texts, some of which are also pseudepigraphal (falsely attributed).

The term Pseudepigrapha generally applies to (extra-canonical) Jewish literature which is excluded from all Bibles, unlike the Apocrypha. - The Catholic and Orthodox churches consider select (Jewish) Apocryphal (pseudepigraphic) books canonical, whereas Protestants, following the Jewish /Hebrew bible's canon in their Old Testament section, do not consider the Jewish Hebrew Bible's Apocrypha section canonical.

- This is seen in the Catholic/Orthodox v Protestant versions of the Bible with the Catholic/Orthodox tradition printing an Apocryphal section between the Old and New Testaments, referred to as a "Secondary Section," following the Hebrew Bible's tradition.

- This section of the Catholic/Orthodox bible is also known as "Between the Testaments" books or, "Secondary" books or, describing the Deutero-Cannonical section of the Catholic/Orthodox bible.

Apocrypha / Deuterocanonical Books - What they are: Books written by Jews between the Old Testament and New Testament periods.

- Catholic/Orthodox view: They are considered canonical and part of the Old Testament.

- Protestant view: Protestants call them the Apocrypha and do not consider them part of the Bible.

- Examples: Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees.

Pseudepigrapha

These are Jewish literary documents which describe a broad, miscellaneous collection of ancient Jewish religious writings from roughly 300 BCE to 300 CE that are not included in any biblical canon - whether Jewish, Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant.

Why the name:- "Pseudepigrapha" means "falsely attributed" because many of these texts were attributed to famous biblical figures who did not write them.

- Catholic/Orthodox/Jewish view:

- They are considered non-canonical, though the Orthodox churches include some texts, like the Book of Enoch, which are categorized as pseudepigrapha from the Chalcedonian Christian viewpoint.

- Significance:

- These texts provide invaluable insight into the religious and cultural context of Early Judaism and Christianity.

Key Differences

- Canon:

- The main difference is their place in the biblical canon. Catholic and Orthodox churches accept the Apocrypha as canonical, but the Pseudepigrapha are not.

- Scope:

- The Pseudepigrapha are a much larger and more diverse collection of texts than the Apocrypha.

- Overlap:

- While some Apocryphal books are technically pseudepigraphal, the term Pseudepigrapha broadly refers to the Jewish works not included in the Septuagint (the Greek Bible) or the Hebrew Bible.

- The Catholic and Orthodox churches consider select (Jewish) Apocryphal (pseudepigraphic) books canonical, whereas Protestants, following the Jewish /Hebrew bible's canon in their Old Testament section, do not consider the Jewish Hebrew Bible's Apocrypha section canonical.

- This is seen in the Catholic/Orthodox v Protestant versions of the Bible with the Catholic/Orthodox tradition printing an Apocryphal section between the Old and New Testaments, referred to as a "Secondary Section," following the Hebrew Bible's tradition.

- This section of the Catholic/Orthodox bible is also known as "Between the Testaments" books or, "Secondary" books or, describing the Deutero-Cannonical section of the Catholic/Orthodox bible.

- What they are: Books written by Jews between the Old Testament and New Testament periods.

- Catholic/Orthodox view: They are considered canonical and part of the Old Testament.

- Protestant view: Protestants call them the Apocrypha and do not consider them part of the Bible.

- Examples: Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees.

Why the name:

- "Pseudepigrapha" means "falsely attributed" because many of these texts were attributed to famous biblical figures who did not write them.

- Catholic/Orthodox/Jewish view:

- They are considered non-canonical, though the Orthodox churches include some texts, like the Book of Enoch, which are categorized as pseudepigrapha from the Chalcedonian Christian viewpoint.

- Significance:

- These texts provide invaluable insight into the religious and cultural context of Early Judaism and Christianity.

- Canon:

- The main difference is their place in the biblical canon. Catholic and Orthodox churches accept the Apocrypha as canonical, but the Pseudepigrapha are not.

- Scope:

- The Pseudepigrapha are a much larger and more diverse collection of texts than the Apocrypha.

- Overlap:

- While some Apocryphal books are technically pseudepigraphal, the term Pseudepigrapha broadly refers to the Jewish works not included in the Septuagint (the Greek Bible) or the Hebrew Bible.

NT Books with Possible Apocryphal / Pseudepigraphal Echoes

Jude: Quotes 1 Enoch and references the Assumption of Moses.

2 Peter: Strong parallels with Jude; reflects shared Enochic/apocalyptic traditions.

Hebrews: Echoes wisdom theology similar to Wisdom of Solomon.

James: Resonates with Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) in its ethical style.

Revelation: Heavily shaped by Jewish apocalyptic tradition (Daniel, 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra).

Jude: Quotes 1 Enoch and references the Assumption of Moses.

2 Peter: Strong parallels with Jude; reflects shared Enochic/apocalyptic traditions.

Hebrews: Echoes wisdom theology similar to Wisdom of Solomon.

James: Resonates with Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) in its ethical style.

Revelation: Heavily shaped by Jewish apocalyptic tradition (Daniel, 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra).

References

Wikipedia - Pseudepigrapha A pseudepigraph (also anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the work is falsely attributed is often prefixed with the particle "pseudo-", such as for example "pseudo-Aristotle" or "pseudo-Dionysius": these terms refer to the anonymous authors of works falsely attributed to Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, respectively.

In biblical studies, the term pseudepigrapha can refer to an assorted collection of Jewish religious works thought to be written c. 300 BCE to 300 CE. They are distinguished by Protestants from the deuterocanonical books (Catholic and Orthodox) or Apocrypha (Protestant), the books that appear in extant copies of the Septuagint in the fourth century or later and the Vulgate (the Latinized version of the whole Bible), but not in the Hebrew Bible or in Protestant Bibles. The Catholic Church distinguishes only between the deuterocanonical (secondary sources to the Bible) and all other books; the latter pseudepigraphae are known as the biblical apocrypha, which in Catholic usage includes select pseudepigrapha. In addition, two books considered canonical in the Orthodox Tewahedo churches, the Book of Enoch and Book of Jubilees, are categorized as pseudepigrapha from the point of view of Chalcedonian Christianity.

In addition to the sets of generally agreed to be non-canonical works, scholars will also apply the term to canonical works who make a direct claim of authorship, yet this authorship is doubted. For example, the Book of Daniel is considered by some to have been written in the 2nd century BCE, 400 years after the prophet Daniel lived, and thus the work may be broadly considered pseudepigraphic. A New Testament example might be the book of 2 Peter, considered by some to be written approximately 80 years after Saint Peter's death. Early Christians, such as Origen, harbored doubts as to the authenticity of the book's authorship.

The term has also been used by Quranist Muslims to describe hadiths: Quranists claim that most hadiths are fabrications[7] created in the 8th and 9th century CE, and falsely attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Wikipedia - Jewish Apocrypha The Jewish apocrypha (Hebrew: הספרים החיצוניים, romanized: HaSefarim haChitzoniyim, lit. 'the outer books') are religious texts written in large part by Jews, especially during the Second Temple period, not accepted as sacred manuscripts when the Hebrew Bible was canonized. Some of these books are considered sacred in certain Christian denominations and are included in their versions of the Old Testament. The Jewish apocrypha is distinctive from the New Testament apocrypha and Christian biblical apocrypha as it is the only one of these collections which works within a Jewish theological framework.

Wikipedia - New Testament ApocryphaThe New Testament apocrypha (singular apocryphon) are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

Wikipedia - Biblical ApocryphaThe Biblical apocrypha (from Ancient Greek ἀπόκρυφος (apókruphos) 'hidden') denotes the collection of ancient books, some of which are believed by some to be of doubtful origin, thought to have been written some time between 200 BC and 100 AD.

The Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches include some or all of the same texts within the body of their version of the Old Testament, with Catholics terming them deuterocanonical books.[6] Traditional 80-book Protestant Bibles include fourteen books in an intertestamental section between the Old Testament and New Testament called the Apocrypha, deeming these useful for instruction, but non-canonical. Reflecting this view, the lectionaries of the Lutheran Churches and Anglican Communion include readings from the Apocrypha.

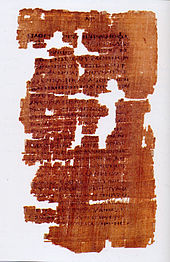

click to enlarge

A pseudepigraph (also anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the work is falsely attributed is often prefixed with the particle "pseudo-", such as for example "pseudo-Aristotle" or "pseudo-Dionysius": these terms refer to the anonymous authors of works falsely attributed to Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, respectively.

In biblical studies, the term pseudepigrapha can refer to an assorted collection of Jewish religious works thought to be written c. 300 BCE to 300 CE. They are distinguished by Protestants from the deuterocanonical books (Catholic and Orthodox) or Apocrypha (Protestant), the books that appear in extant copies of the Septuagint in the fourth century or later and the Vulgate (the Latinized version of the whole Bible), but not in the Hebrew Bible or in Protestant Bibles. The Catholic Church distinguishes only between the deuterocanonical (secondary sources to the Bible) and all other books; the latter pseudepigraphae are known as the biblical apocrypha, which in Catholic usage includes select pseudepigrapha. In addition, two books considered canonical in the Orthodox Tewahedo churches, the Book of Enoch and Book of Jubilees, are categorized as pseudepigrapha from the point of view of Chalcedonian Christianity.

In addition to the sets of generally agreed to be non-canonical works, scholars will also apply the term to canonical works who make a direct claim of authorship, yet this authorship is doubted. For example, the Book of Daniel is considered by some to have been written in the 2nd century BCE, 400 years after the prophet Daniel lived, and thus the work may be broadly considered pseudepigraphic. A New Testament example might be the book of 2 Peter, considered by some to be written approximately 80 years after Saint Peter's death. Early Christians, such as Origen, harbored doubts as to the authenticity of the book's authorship.

The term has also been used by Quranist Muslims to describe hadiths: Quranists claim that most hadiths are fabrications[7] created in the 8th and 9th century CE, and falsely attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

The Jewish apocrypha (Hebrew: הספרים החיצוניים, romanized: HaSefarim haChitzoniyim, lit. 'the outer books') are religious texts written in large part by Jews, especially during the Second Temple period, not accepted as sacred manuscripts when the Hebrew Bible was canonized. Some of these books are considered sacred in certain Christian denominations and are included in their versions of the Old Testament. The Jewish apocrypha is distinctive from the New Testament apocrypha and Christian biblical apocrypha as it is the only one of these collections which works within a Jewish theological framework.Wikipedia - New Testament Apocrypha

The New Testament apocrypha (singular apocryphon) are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.Wikipedia - Biblical Apocrypha

The Biblical apocrypha (from Ancient Greek ἀπόκρυφος (apókruphos) 'hidden') denotes the collection of ancient books, some of which are believed by some to be of doubtful origin, thought to have been written some time between 200 BC and 100 AD.

The Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches include some or all of the same texts within the body of their version of the Old Testament, with Catholics terming them deuterocanonical books.[6] Traditional 80-book Protestant Bibles include fourteen books in an intertestamental section between the Old Testament and New Testament called the Apocrypha, deeming these useful for instruction, but non-canonical. Reflecting this view, the lectionaries of the Lutheran Churches and Anglican Communion include readings from the Apocrypha.

click to enlarge