Processual Metanoian Language- a turning, reorienting, or re-becoming from within lack or incompleteness- an event of creativity arising from within relational fracture- the unfolding of a caustic rupture that becomes generatively transformative

This essay grows out of a tension many of us feel today: that we are living in a world where meaning is both desperately needed and perpetually slipping through our fingers.

- Modernism promised clarity.

- Postmodernism exposed fragmentation.

Metamodernism tries to hold both together - sincerity with irony, hope with doubt - but often slips into a quiet longing from some higher vantage point that might finally make sense of everything.

That longing carries a risk. It can tempt us into believing that we could rise above language, above contradiction, above our situated human condition, and speak from some pure and stable place.

This is exactly what Lacan warns against with his famous line:

“There is no metalanguage.”

His point is harsh: there is no language outside language, no final framework that explains all frameworks, no way to escape the fractures we’re born into.

And yet - those fractures are not linguistic prisons. They are openings:

- Where Lacan sees enclosure, Whitehead sees process.

- Where Lacan sees structure, Whitehead sees becoming.

- Where Lacan sees no escape, Whitehead sees continual creative advance.

This essay is written in the spirit of rupture - not as rebellion, but as a gentle breach, a creative opening within the very fracture Lacan describes. It’s an attempt to show that even if we cannot climb above language, we can still transform it from within. Novelty is real. Creativity is real. New forms of meaning are always possible.

This is not a claim to mastery. It is a fidelity to our incompleteness. A metamodern way of speaking from the wound instead of pretending we can heal it from outside.

Introduction

Lacan’s famous claim - “There is no metalanguage” - is one of those deceptively simple lines that reshaped entire eras of thought. To understand why, we need a clear sense of what “metalanguage” even means.

A metalanguage is basically a language above language - the fantasy that we could climb above all our messy human meanings and speak from a pure, final vantage point. It’s the dream of a perfect map, a perfect theory, a perfect clarity that stands outside the world’s contradictions.

But the idea goes deeper.

A metalanguage is the fantasy that we could somehow step outside our own messy human perspectives and speak from a place of perfect external clarity - as if we could climb a ladder and look down at meaning from above. A true metalanguage would promise:

- a final map of meaning

- a perfect, untainted vantage point

- a place where contradictions vanish

- a language that explains all languages

- a view of the system from outside the system

In everyday life, this shows up as the quiet hope for “objective truth without bias,” or “the final theory that makes it all make sense.” A God’s-eye dictionary. A cosmic commentator’s booth. A place beyond the mess.

Lacan’s point is cold and uncompromising:

- We can never stand outside language.

- We can never step into pure perspective.

- We can never escape our own histories, wounds, or desires.

We are always inside our own frame. We are always speaking from inside the wound.

This insight dismantles the illusion of mastery that modernism coveted and certain strands of metamodernism still desire - the hope that a final synthesis might one day pull the fragments together.

But Lacan stops at the fracture. He reveals the impossibility of transcendence, yet he leaves the wound untouched, inert, unhealed - a static condition of lack, a metaphysical cage.

Lacan stops at the deconstruction when exposing the impossibility of metalanguage by not following the fracture into its creative depths.

This is where Whitehead becomes indispensable. Where Whitehead ruptures Lacan from within that very wound.

Whitehead accepts the impossibility of metalanguage, yet refuses the stasis of Lacan’s symbolic order. Reality, for Whitehead, is not structural imprisonment but processual becoming. Creativity is metaphysical. Novelty is real. Transformation is woven into the bones of the universe.

Whitehead agrees that we never find a place outside the system - but he refuses to treat the system as static, closed, or final. For Whitehead, reality itself is becoming. Language is alive. Meaning evolves. Novelty is metaphysically real. The symbolic order is not a cage; it is a living, breathing, organism.

But the possibility of new language emerging from inside the very fractures Lacan describes.

-

Metanoetic Process Language (Whitehead):language that turns, reorients, and becomes.

-

Generative Language (post-Whitehead):language that births new meaning from within fracture.

-

Autopoietic Language:language that self-organizes and evolves.

-

Angiogenic Language:language that grows new pathways, new lifelines of meaning.

-

Cruciform–Resurrectional Language:language that dies to old forms and rises in creative transformation.

This constellation forms a metamodern counter-movement to Lacan - not by offering a vantage point above language, but by showing language itself as alive, emergent, and capable of becoming beyond its prior limits.

We do not need a metalanguage.

We need the courage to create a new language, a new attitude, a new ending, from within the wound.

This essay then is about that rupture. To explore the metamodern, processual breach created by static language and static concepts.

To explore what it means to inhabit incompleteness rather than escape it.

To explore how rupture becomes generative when we follow Whitehead instead of stopping with Lacan.

Essentially, we do not need a metalanguage. We need the courage to create a new language, a new attitude, a new ending, from within the wound.

- Birthing from within to reach beyond.

- Language as natality, as creative explosion.

- Self-making, self-organizing, recursively evolving.

- Language as a living system.

Wound-Breakage + Fracture Healing

Inside-Out "Predator" Birthing (mythic-radical version)

- A “hyperobject” version of radical re-creation

- Of forced emergence under pressure

- A radical birth from within or under existential intensity

Lacan’s prohibition - “there is no metalanguage” - is not merely a linguistic observation; it is a metaphysical critique. It dismantles a very old dream: that we could step outside our own symbolic reference frame and finally speak truth (as we think we known and understand it) from some utopian plane of perfection, with objectively, and as whole people.

For Lacan, (high-conceptual) language is not a neutral tool but the very structure in which subjectivity may form. The symbolic order precedes us. It shapes our desire, our concepts, our thought, our sense of self. And because it precedes us, we can never get outside of it to speak from a purer or more stable ground.

This is why metalanguage, in Lacan’s view, is a fantasy - a famously alluring and seductive one:

- the fantasy of personal or societal mastery

- the fantasy of integrative coherence

- the fantasy of complete understanding

- the fantasy of a “view from nowhere but everywhere”

This is the heart of Lacan’s critique.

And in many ways, it is correct.

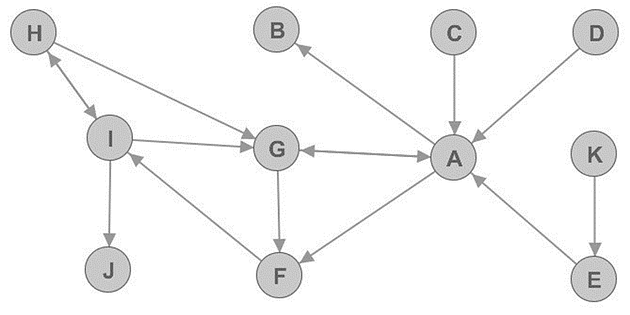

But Lacan’s insight is bound to a particular kind of metaphysics - a structural world where language forms a superjective grid: a looping, self-reinforcing matrix in which subjective and objective experience collapse into a single symbolic enclosure. Within this framework, the subject is defined by lack or incompleteness, and desire is perpetually deferred into the endless chain of signifiers. His “no metalanguage” becomes a sealed ontological chamber.

This is the moment where Whitehead enters - not as a contradiction, but as a rupture.

Superjective (clarification): In this context, a superjective framework is one that loops back upon itself, containing both subjective and objective experience within a single, self-generating symbolic order — a fractal of consciousness or meaning. By contrast, an abjective frame would be neither subjective nor objective, an expelled or exterior remainder with no position inside the symbolic circuit.

Application for Section I -

Within these enclosures, God becomes trapped in the very frameworks paradoxically designed to reveal God. The doctrines become the cage:

- God is boxed into punitive schemas.

- Salvation becomes a juridical transaction.

- Violence, wrath, and terror are attributed to divine necessity.

- Eschatology becomes cosmic retribution rather than relational healing.

- Human diversity becomes a threat to theological purity.

This produces a superjective theology - a looping, self-validating symbolic frame where every question collapses into the system’s own predetermined answers. The Bible becomes an epistemic fortress. God becomes indistinguishable from the doctrinal machinery meant to point to God.

Nothing new can enter.Nothing relational can breathe.Nothing living can grow.

meaning is static, desire is lack, the symbolic is a cage.

Whitehead’s metaphysics ruptures this enclosure by revealing that reality - and therefore God - is fundamentally processual, relational, creative, and open-ended.

static metaphysics produces closed systems;process metaphysics produces generative possibilities...

It is no accident that such frameworks produce fear-based religions, punitive cosmologies, and existential terror disguised as orthodoxy. When language is static, God becomes static - and static gods always collapse into violence.

This is exactly the moment where Whitehead’s process metaphysics becomes not only a philosophical alternative, but a theological liberation.

~ continue to Part B of Essay I ~