|

| The Ark Encounter by Ken Hamm near Cincinnati, Ohio |

|

| A popular view of Noah's Ark |

|

| Wikipedia - Noah's Ark |

|

| The Ark Encounter by Ken Hamm near Cincinnati, Ohio |

|

| A popular view of Noah's Ark |

|

| Wikipedia - Noah's Ark |

Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and then Babylonian.

The Sumerians were called the «Black people». They probably split from the earlier civilisation of Aratta in the Armenian Highlands/Ukraine.

There was a huge flood which caused mass destruction of the contemporary civilisations when the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea connected, some time from 4000–5000 BC.

It may be that this flooding caused the myth of the biblical flood milleniums later.

- Quora: Shivan Perumaal

Sumerians were neither Indo-European nor Semitic people, but everyone else on this list was largely Semitic - as in, they spoke Semitic languages (Babylonians and Assyrians spoke Akkadian, Assyrians today speak various Aramaic dialects and Akkadians spoke Akkadian themselves).

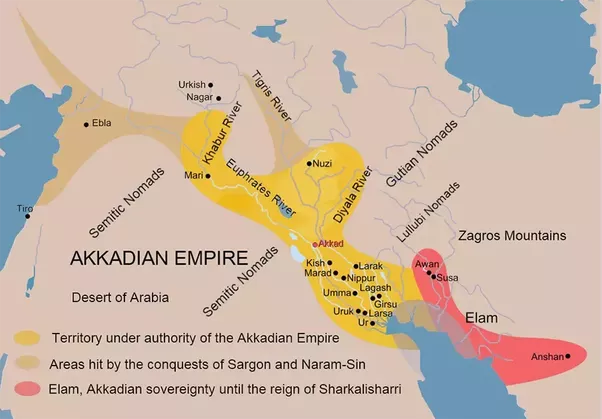

Akkadians were a Semitic-speaking people who ruled over Mesopotamia when they conquered Sumer and eventually established an empire - Akkadian Empire, which reached its peak during the rule of Sargon of Akkad.

|

| Akkadian Empire |

Assyrians ruled Northern Mesopotamia, while Chaldeans ruled in the south, in an empire called Babylon or Babylonia. Consequently, the Assyrians are the Assyrians, while the Chaldeans are/were the Babylonians.

Assyrians formed a military dynasty while Babylonians became merchants and agriculturalists.

Assyrians worship animism or animistic beliefs, while Babylonians are polytheistic. They worship several gods and thousands of minor gods.

- Quora: Alice Giam

|

| Assyrian Empire |

On the map are two major cities, Asshur the center of Assyria, and Babylon. Each was an empire at different times.However, Babylon was the center of an empire for only two relatively brief periods. For much of the time, it was subject to Assyria.The Assyrians lived in that area from at least 2600 BCE. Apparently, they were influenced by Akkad and spoke AkkadianBabylon, however, was founded by Amorites who had moved into Mesopotamia around 2000 from northern Canaan. In 1792, Hammurabi established a kingdom and built the city of Babylon up from a town. His empire rapidly declined after his death in 1750.Sometime after that, the Assyrians gained control over Babylon, although Babylon remained an important religious center.In 625, as the Assyrian Empire finally began to fail, Babylon joined the Medes and others in rebelling against Assyria, which was wiped out by 609. The Babylonians had a second empire until 539 when the Medes and Persians conquered Babylon. Babylon remained an important city for a long time after that.Bottom line, Babylon gets a lot of credit for what Sumer and Akkad accomplished, but it wasn’t a great power for any length of time. Instead, it was an important trading and religious center.The Babylonians’ big significance was taking the Jews into exile from 605–586, when they destroyed Jerusalem. The Medes and Persians returned the Jews and other exiled nations in 539.

- Quora: Steve Page

|

| Babylonian Empire + Wikipedia |

Assyrian vs Babylonian

The two neighboring sister-states of ancient Mesopotamia competed for dominance and as such grew widely different in character.

History

Assyria took its name from the town of Ashur, which was the main town but it may also apply to the wide empire that was captured and ruled by the Assyrians. Assyria had better climate than Babylonia owing to the fact that it was located in a highland region north of Babylonia. Assyrians were not entirely Semitic and their true origin is not really known. Their culture, however, was largely indebted to the Babylonians, the Hurrians and the Hittites. Their religion was an adoption from the Babylonians except that the presiding god of the city of Ashur became Assyria’s chief deity. Their nature of worship was animistic.

Babylonia was located at the eastern end of the fertile crescent of west Asia with its capitol as Babylon. At times it was referred to as the land of the Chaldeans. There were originally two political divisions namely Sumer and Akkad. Both the Assyrians and Babylonians made use of the Cuneiform script and all people including royalty, priests, merchants and teachers relied on writing. Nebuchadnezzar ruled Babylon for many years, his reign eventually becoming one of the longest and most accomplished in human history. Some historical moments during his reign include twice capturing. Jerusalem and destroying it and the buildings and walls he built in the city, which were admired by Greek historians.

Organization

While merchants and agriculturalists sprung up in Babylonia, Assyrians became more militaristic, forming an organized military camp ruled over by an autocratic king as the supreme ruler. Successful generals then founded Assyrian dynasties and the king was the autocratic general of an army, who was in the early days surrounded by feudal nobility. These nobles were aided, from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser onwards, by an elaborate bureaucracy. The king’s palace was more sumptuous than the worship houses (temples) of the gods from which it was separate. All people were soldiers or little else to the extent that even the sailor belonged to the state. This resulted to the sudden collapse of the Assyrian during the age of Ashurbanipal when it was drained of its warrior population. In the neighboring Babylonia, the priesthood was the highest authority with priests having been raised to the throne by the revolution. Under the control of a powerful hierarchy, the Babylonian king remained a priest to the end.

Summary

1. Assyria was located north of Babylonia, its highland location giving it better climate than Babylonia.

2. Assyrians formed a military dynasty whereas Babylonians became merchants and agriculturalists.

3. The supreme ruler in Assyria was an autocratic king while in Babylonia, priesthood was the highest authority.

4. Assyrians’ nature of worship was animistic and that of idolatry while for Babylonians it was in a Supreme God.

- Source: Wikipaedia / Quora: Mary Bennett

Baby boomers are the eldest, born between the years 1946 and 1964.

Generation X follows, and they were born between 1965 and 1980.

Next comes Generation Y (more commonly known as Millennials), born between roughly 1981 and 1994.

The youngest generation in today's workforce is Gen Z, who were born between 1995 and 2009.

Paul Capetz – a real deal Calvinist, professional theologian, & Fuller Family Christmas Guest decided to replay to my sovereignty smack talking this week with a Calvinist rejoinder. This is awesome and I am sure it will inspire you to get his book on the history of the doctrine of God (it’s awesome & for general audience) and check out the podcast 500th birthday we threw for Calvin. Now…here’s Paul!

I applaud Tripp Fuller for initiating this stimulating and provocative discussion about Calvin’s theology and the question of metaphysical determinism. As someone with a deep appreciation for Calvin (I have taught 6 seminars on Calvin at my school in the past 20 years as well as written a book on Calvin’s understanding of religion), I hope I can add some words that are intended not polemically but thoughtfully, thereby giving expression to some of the issues with which I have had to wrestle as a student and teacher of Calvin.

Let me begin by stating that of all the premodern theologians, Calvin best captures the whole of what is important in my understanding of Christian faith. He is deeply indebted to Luther in his doctrine of justification, he is profoundly Augustinian in his understanding that religion is a matter of the heart and its affections, and he veers in the direction of Wesley with his emphasis upon sanctification. Moreover, his high view of the Old Testament and his belief that the third use of the law is its primary purpose account for his oft-noted affinities with Judaism and thus make him an important bridge between Jews and Christians. Finally, one cannot help but notice that Calvin is also vitally concerned with the political life and the shaping of society in the direction of greater justice for all and care for the needy. In each of these respects, I follow Calvin without reservation!

But there is another side of Calvin that explains the stereotypically negative picture of him. First, there is his utterly deterministic view of divine providence. Not only does God allow events we deem evil to occur but God is the active agent behind each and every event. Of course, Calvin strives valiantly not to impugn God’s character by accusing God of injustice. Still, it is hard for even the most sympathetic reader of Calvin’s theology not to find a logical problem in his theology at this point. Second, his doctrine of election means that before creation God has predestined who is to be a recipient of salvation and who is to be damned. Again, it is hard not to suspect that his position here leads to insuperable problems. After all, what is the point of preaching the gospel if some people (indeed, the majority of people!) are incapable of responding to it by virtue of God’s decision to damn them before they are born?

As a theologian I employ an existential hermeneutic, if I may call it that. What I mean is that I always look for the existential question being addressed behind any particular theological statement of doctrine. So, for example, it is clear in the above two cases that Calvin is addressing two concerns near and dear to his heart. First, his doctrine of providence is concerned to assure us that the events of personal life and history are meaningful because God is actively involved in all events. Second, his doctrine of election is concerned to uphold the priority of God’s grace in human salvation. But, having identified the motivating questions behind his formulations of these doctrines, we have to ask: are there other ways we could affirm these religious points without Calvin’s problematic interpretations of these doctrines? This is how I believe we should approach the question of whether metaphysical determinism is really as essential to Calvin’s theology as most of those who call themselves “Calvinists” believe to be the case.

Process theologians and others with related viewpoints have correctly pointed to the influence of Greek metaphysical assumptions upon all classical Christian theology, whether Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, or Protestant. There can be no serious doubt, I think, that the classical tradition is guided by an unquestioned axiom regarding God’s impassibility. I have found process theology particularly helpful in offering new ways to think about this issue, especially its insistence that there can be a perfect exemplification of receptivity in God. If we let go of the classical bias that looks upon change and passibility as imperfections—and I think we should—then there might be another way of working through the problematic aspects of Calvin’s theology identified above.