Baby boomers are the eldest, born between the years 1946 and 1964.

Generation X follows, and they were born between 1965 and 1980.

Next comes Generation Y (more commonly known as Millennials), born between roughly 1981 and 1994.

The youngest generation in today's workforce is Gen Z, who were born between 1995 and 2009.

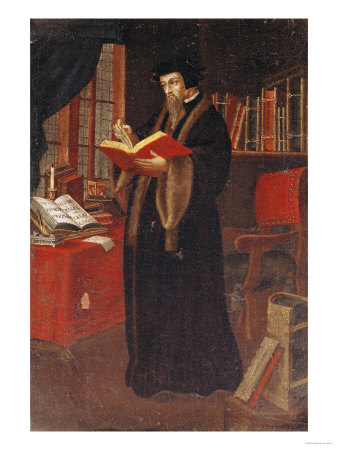

Paul Capetz – a real deal Calvinist, professional theologian, & Fuller Family Christmas Guest decided to replay to my sovereignty smack talking this week with a Calvinist rejoinder. This is awesome and I am sure it will inspire you to get his book on the history of the doctrine of God (it’s awesome & for general audience) and check out the podcast 500th birthday we threw for Calvin. Now…here’s Paul!

I applaud Tripp Fuller for initiating this stimulating and provocative discussion about Calvin’s theology and the question of metaphysical determinism. As someone with a deep appreciation for Calvin (I have taught 6 seminars on Calvin at my school in the past 20 years as well as written a book on Calvin’s understanding of religion), I hope I can add some words that are intended not polemically but thoughtfully, thereby giving expression to some of the issues with which I have had to wrestle as a student and teacher of Calvin.

Let me begin by stating that of all the premodern theologians, Calvin best captures the whole of what is important in my understanding of Christian faith. He is deeply indebted to Luther in his doctrine of justification, he is profoundly Augustinian in his understanding that religion is a matter of the heart and its affections, and he veers in the direction of Wesley with his emphasis upon sanctification. Moreover, his high view of the Old Testament and his belief that the third use of the law is its primary purpose account for his oft-noted affinities with Judaism and thus make him an important bridge between Jews and Christians. Finally, one cannot help but notice that Calvin is also vitally concerned with the political life and the shaping of society in the direction of greater justice for all and care for the needy. In each of these respects, I follow Calvin without reservation!

But there is another side of Calvin that explains the stereotypically negative picture of him. First, there is his utterly deterministic view of divine providence. Not only does God allow events we deem evil to occur but God is the active agent behind each and every event. Of course, Calvin strives valiantly not to impugn God’s character by accusing God of injustice. Still, it is hard for even the most sympathetic reader of Calvin’s theology not to find a logical problem in his theology at this point. Second, his doctrine of election means that before creation God has predestined who is to be a recipient of salvation and who is to be damned. Again, it is hard not to suspect that his position here leads to insuperable problems. After all, what is the point of preaching the gospel if some people (indeed, the majority of people!) are incapable of responding to it by virtue of God’s decision to damn them before they are born?

As a theologian I employ an existential hermeneutic, if I may call it that. What I mean is that I always look for the existential question being addressed behind any particular theological statement of doctrine. So, for example, it is clear in the above two cases that Calvin is addressing two concerns near and dear to his heart. First, his doctrine of providence is concerned to assure us that the events of personal life and history are meaningful because God is actively involved in all events. Second, his doctrine of election is concerned to uphold the priority of God’s grace in human salvation. But, having identified the motivating questions behind his formulations of these doctrines, we have to ask: are there other ways we could affirm these religious points without Calvin’s problematic interpretations of these doctrines? This is how I believe we should approach the question of whether metaphysical determinism is really as essential to Calvin’s theology as most of those who call themselves “Calvinists” believe to be the case.

Process theologians and others with related viewpoints have correctly pointed to the influence of Greek metaphysical assumptions upon all classical Christian theology, whether Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, or Protestant. There can be no serious doubt, I think, that the classical tradition is guided by an unquestioned axiom regarding God’s impassibility. I have found process theology particularly helpful in offering new ways to think about this issue, especially its insistence that there can be a perfect exemplification of receptivity in God. If we let go of the classical bias that looks upon change and passibility as imperfections—and I think we should—then there might be another way of working through the problematic aspects of Calvin’s theology identified above.

No comments:

Post a Comment