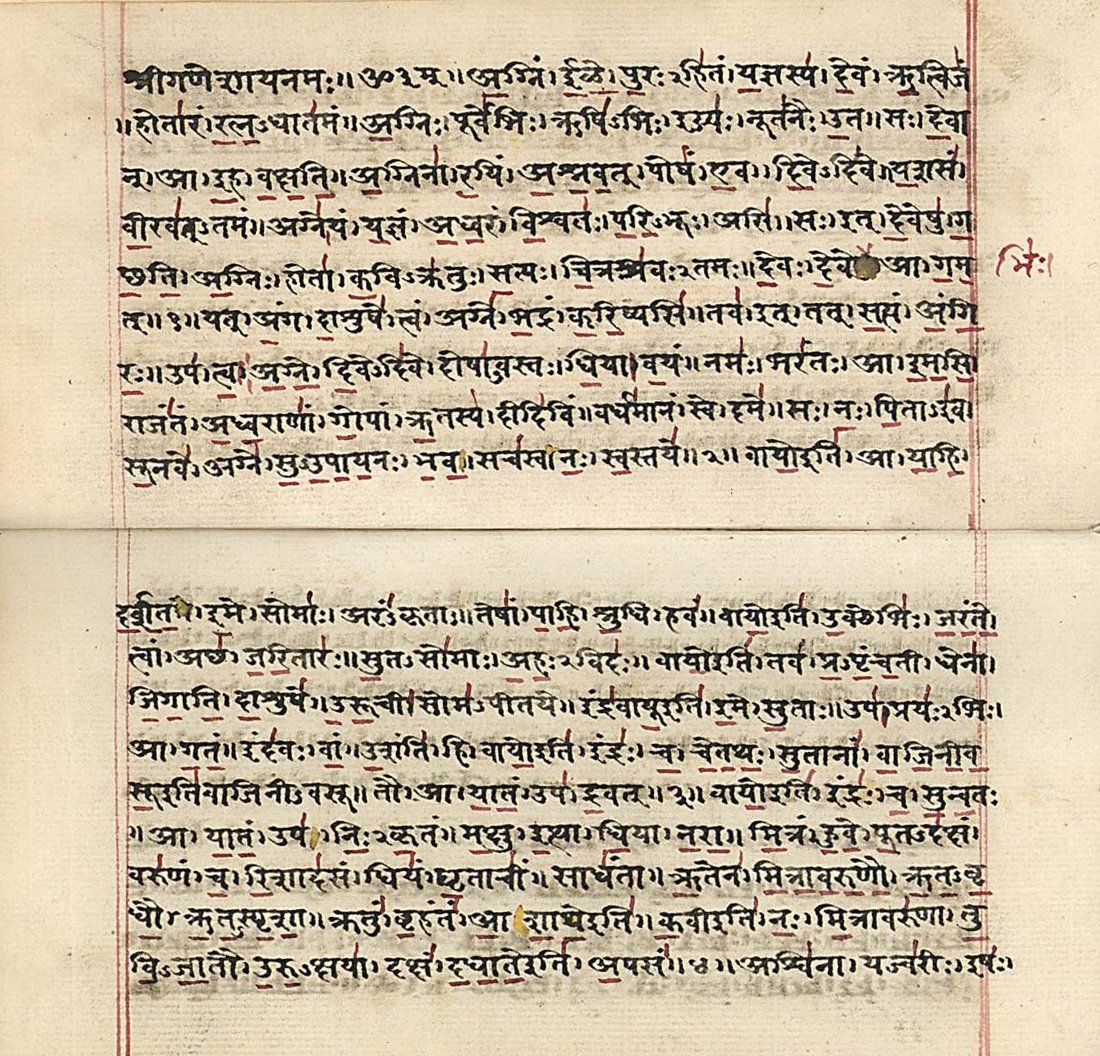

“Tat tvam asi” - “You are That.”

“Ayam atma Brahma” - “This self is Brahman.”

This nondual insight overturns the entire logic of ritual religion:

- There is no need to appease gods when the divine is within one’s own deepest nature.

- Reality is not maintained externally but recognized internally.

- Liberation is achieved not by action, but by awakening.

This places India at the forefront of a global Axial philosophy: where Inward-introspection becomes metaphysics.

C. The Nature of Reality: From Multiplicity to UnityThe Upanishads propose a universe in which multiplicity is real but derivative. Beneath the diverse forms of experience lies a single, undivided reality.

This metaphysical unity takes several related forms:

- Sat - Being

- Cit - Consciousness

- Ānanda - Bliss or fullness

- Brahman - The infinite ground of all that is

In this vision, the world is neither illusion nor brute matter - it is a manifestation of a deeper, undivided consciousness. The purpose of life is not to manipulate ritual forces but to see through the fragmented world to the unity beneath it.

This shift moves Indian religion from cosmology to ontology, from ritual mechanics to interior metaphysics.

D. Karma and Dharma: Moral Causation in a Conscious UniverseBy the time of the early Upanishads, the doctrine of karma - the principle that actions have consequences across lifetimes - had begun to crystallize.

But the Upanishads give to karma a new depth: karma becomes not merely a metaphysical law but a moral architecture embedded in the fabric of reality.

1. Karma as Moral Order

- Every action leaves an imprint.

- Every intention shapes future becoming.

- Ethics is woven into the causal structure of the cosmos.

2. Dharma as Alignment

- Dharma (order, duty, rightness) becomes the way beings align themselves with cosmic truth.

- To act in accord with dharma is to participate in the unfolding of reality with clarity and non-harm.

This moral metaphysics marks India’s Axial contribution: liberation is a matter of ethical insight as well as metaphysical realization.

E. The Upanishadic Path: Knowledge, Meditation, and LiberationLiberation (mokṣa) is the ultimate goal.

Not heaven, not prosperity, not worldly success.

Liberation is freedom from ignorance, rebirth, and suffering achieved through:

-

Self-inquiry (ātma-vicāra)

-

Meditation (dhyāna)

-

Renunciation of egoistic desire

-

Cultivation of discriminating insight, discernment (viveka)

The Upanishadic sage is not a priest, and not quite a philosopher in the Greek sense. He is a contemplative - a seeker of the real, an experimenter in consciousness.

The Upanishads thus inaugurate the great Indian tradition of interior experimentation, a legacy that will shape Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, yoga, tantra, and later global spiritual movements.

Section II SummaryThe Upanishads represent a decisive Axial transformation: the birth of metaphysical interiority and the discovery of consciousness as the foundation of reality. The unity of Atman and Brahman marks a turning point in global religious thought, offering a vision in which the sacred is not external but intrinsic to the self.

III. The Śramaṇa Movements: Renunciation, Nonviolence, and the Rise of Liberation Traditions

While the Upanishads initiated an inward turn within the Vedic tradition itself, a parallel movement arose outside the authority of priest and ritual. These were the śramaṇas - “strivers,” wandering renouncers - who left household life to pursue direct spiritual awakening. Their presence marks one of the most dynamic Axial developments in India: a revolution in which liberation became experiential, ethical, and universally accessible, rather than the preserve of ritual specialists.

In the śramaṇa world, truth was not inherited through lineage or revealed through sacred sound - it was discovered through discipline, insight, meditation, and moral clarity. This movement produced some of the most influential figures in world religion, including the Buddha (the "Awaklened One," 563 or 480 BCE) and Mahāvīra/Vardhamana (a Jain Reformer and Spiritual leader, 599 BCE), and contributed to a sweeping redefinition of spiritual life across the subcontinent.

A. The Renouncer Ideal: Leaving the World to Understand It

Śramaṇa traditions arose as a critique of Vedic ritualism and the growing social complexity of the Second Urbanization. As cities expanded, political instability increased, and wealth concentrated, many individuals found household life spiritually confining. They adopted a new ideal: renunciation (saṃnyāsa).

The Renouncer Path Involved:

- Leaving home and social obligations

- Rejecting caste constraints

- Practicing celibacy, voluntary poverty, and wandering

- Engaging in meditation and ascetic discipline

- Seeking direct knowledge of liberation

The renouncer’s authority rested not on ritual but on experience. This shift democratized spiritual access: liberation was open to all who sought it sincerely, regardless of birth or status.

Renouncers transformed the cultural imagination. They redefined what counted as a meaningful life.

B. Buddhism: Liberation Through Insight, Compassion, and the Cessation of Suffering

One renouncer would articulate this interior revolution with unparalleled clarity: Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha (c. 563-483 BCE). Emerging directly from the śramaṇa milieu, the Buddha reframed the human challenge not as ritual impurity but as existential suffering (dukkha) arising from desire, ignorance, and impermanence.

Key Buddhist Contributions to the Liberation Paradigm:

1. Suffering as the Fundamental Human Problem

The Buddha identified suffering, not cosmic disorder, as the condition that binds beings to rebirth.

2. No Eternal Self (Anātman)

In deliberate contrast to the Upanishadic identity of Atman and Brahman, the Buddha taught that the sense of a fixed self is an illusion. Liberation lies in seeing through this illusion, not identifying with it.

3. Dependent Origination (Pratītya-samutpāda)

Reality is a relational process without fixed substances - an early expression of processual metaphysics.

4. The Eightfold Path

Ethical conduct, meditation, and wisdom form a holistic path of experiential insight.

5. Compassion (Karunā)

Buddhism infused the liberation quest with profound ethical responsibility for all beings.

- The Buddha internalized, simplified, and universalized the liberation process.

- No gods needed to be appeased; no rituals were required.

- Liberation was accessible through clarity, meditation, and compassion.

C. Jainism: Liberation Through Radical Nonviolence and Moral Purity

Another śramaṇa movement, emerging at nearly the same time as Buddhism, was Jainism, led by Mahāvīra (c. 599–527 BCE). Jainism represents the ethical extreme of the śramaṇa ideal, emphasizing nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and the purification of karma through ascetic rigor.

Distinctive Jain Contributions Include:

1. The Eternity of the Soul (Jīva)

Unlike Buddhism, Jainism affirmed an eternal, individual soul bound by karmic matter.

2. Karmic Materialism

Karma is understood as a subtle substance that literally adheres to the soul.

Liberation requires burning off all karmic residue.

3. Nonviolence as Cosmic Principle

Ahiṃsā becomes the supreme religious value, extending to animals, insects, plants, and even microorganisms.

4. Extreme Asceticism

Practices include fasting, meditation, truthfulness, and sometimes non-possession to the point of nudity.

5. Liberation (Mokṣa) as the Soul’s Unbinding

The liberated soul rises to the top of the cosmos, freed from all karmic accretions.

Jainism brings an uncompromising moral intensity to the Axial project of liberation - where ethics becomes metaphysics, and purity becomes salvation (contra to Jesus' teachings that he became mankind's purity in sacrificial atonement).

D. Shared Śramaṇa Themes: Interior Discipline and the Human Condition

Despite their differences, Buddhist, Jain, and other śramaṇa traditions such as Ājīvika (sic, absolute fatalism and/or extreme determinism; no freewill, just fate) and various yogic paths (sic, personal and/or group practices or disciplines to control mind and body to attain liberation) share several foundational commitments that mark a clear break from Vedic religion.

Shared Śramaṇa Characteristics:

- Karma and rebirth as the central human problem

- Liberation as the supreme goal (mokṣa/nirvāṇa)

- Ethical discipline as a spiritual necessity

- Meditation as the route to knowledge

- Renunciation as a valid and often superior path

- Direct experience over inherited ritual

- Suffering and ignorance as existential conditions to be overcome

These shared principles created a new religious culture in India in which inner transformation replaced outward performance as the highest spiritual priority.

E. The Dialogue Between Śramaṇa and Brahmanical Traditions

The śramaṇa movements did not remain external adversaries. Over centuries, they influenced Brahmanical thought deeply, contributing to:

- the rise of yogic practices

- the development of Sāṃkhya metaphysics (spirit and body; consciousness and matter)

- the refinement of karma/dharma theories

- the growth of renunciation within Hinduism

- the emergence of Vedānta ("the end of the Vedas" referring to the Upanishads) as a synthetic philosophical tradition

Thus the Indian Axial Age is not a story of rupture but of dialogue -

- a dynamic interplay between ritual specialists and contemplative seekers,

- between social duty and personal liberation,

- between cosmic order and existential insight.

Section III Summary

The śramaṇa revolution transformed Indian religion by situating liberation within the human condition itself. Buddhism emphasized insight and compassion; Jainism emphasized nonviolence and moral purity; other renouncer traditions emphasized fate, meditation, or metaphysics. Together, they democratized spiritual life (made it accessible to the public), challenged ritual authority, and shifted the locus of religious meaning inward - deepening the Axial quest for an awakened, ethical, and liberated self.

IV. Karma, Dharma, and the Emergence of a Moral Universe

By the late Iron Age, Indian thought had undergone a profound transformation. The ritual cosmos of the early Vedic world - structured by sacrifice, priesthood, and cosmic maintenance - gave way to an interiorized, ethically charged vision of reality in which moral causation, duty, and spiritual-liberation became the central organizing principles of life. This transformation produced one of India’s greatest intellectual achievements: the conception of a moral universe, where action and intention carry consequences across lifetimes, and alignment with cosmic truth becomes the measure of spiritual maturity.

A. Karma: The Architecture of Moral Causation

Although the early Vedas contain only rudimentary hints of karmic thinking, by the time of the Upanishads and the Śramaṇa traditions, karma had become a fully articulated metaphysical law.

1. Beyond Ritual Causation - Where Vedic sacrifice presupposed a mechanical relationship between rite and result, karma introduced an ethical dimension. Action mattered not because it pleased the gods, but because it shaped the soul. Karma thus replaced ritual causation with moral causation - this is profoundly marks the essence of an socio-religious Axial shift.

2. Intention Matters - Unlike earlier cosmologies, karma emphasizes intention (cetanā) as the primary moral determinant. Not just what one does, but why one does what one does.

3. There exists Consequences Across Multiple Lifetimes - Karma extends the scope of moral accountability beyond a single lifespan, linking (re-incarnation):

- character,

- desire,

- attachments, and

- ignorance

to the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra).

4. Karma as Process - Karma is not fate. It is processual becoming - an ever-evolving trajectory shaped by ongoing choices. In this sense, karma anticipates later process philosophy: actions generate tendencies, tendencies generate patterns, and patterns generate the contours of one’s future becoming.

*Of Note: Though process philosophy does not claim exclusive ownership of truth, it functions instead as a relational and temporal meta-framework capable of recognizing processual dynamics - becoming, relation, contingency, novelty, and responsiveness - within all viable systems of thought. Even non-processual philosophies which privilege stasis, substance, or abstraction nonetheless depend in practice upon processual realities: development, change, interaction, and historical emergence.

In this sense, process philosophy is an integrative meta-framework rather than a competing doctrinal system. It does not claim that all philosophies are already process philosophies, but that all coherent systems of thought necessarily rely upon processual realities - temporality, relation, becoming, interaction, and emergence - even when these processual elements are conceptually minimized or denied.

Hence, process philosophy functions as a meta-ontological lens capable of identifying dynamic, relational, temporal, and becoming-oriented elements already present - often implicitly - within any coherent system of thought. This is a distinctly Whiteheadian claim and is philosophically defensible. Whitehead himself expressed it more gently when observing that "Actuality is process, even when philosophical or theological systems theoretically deny it."

It is in this way that India's karmic (relational-causal) systems resonate structurally with process thought without being fully invested in process itself, emphasizing relationality, impermanence, and responsive-becoming. Similarly, there are many non-Western philosophical and religious traditions which resonate more readily with process thought which is why one senses a kinship of outlook and response with Eastern and Mid-Eastern meta-frameworks. - re slater

B. Dharma: Alignment with Cosmic Order

Alongside karma, the concept of dharma emerged as an ethical orientation which aligned individuals with the presumed moral structure of the cosmos. Dharma has no simple English equivalent. It is simultaneously:

- law

- duty

- rightness

- truth

- order

- relational responsibility

- moral harmony

1. From Ritual Order (Ṛta) to Moral Order (Dharma) - In early Vedic religion, ṛta referred to the cosmic order maintained through ritual. Over time, this became internalized as dharma - an ethical order maintained through virtuous living.

2. Social and Spiritual Dimensions

- In Brahmanical thought, dharma reflects social responsibilities (varṇa-āśrama dharma).

- In Śramaṇa traditions, dharma reflects universal ethical principles (nonviolence, truth, compassion).

3. Dharma as a Way of Being-in-the-World - To act according to dharma is not to obey a divine command but to harmonize oneself with the deep structure of reality. This gives dharma its metaphysical potency: to live well is to participate in cosmic truth.

C. Saṃsāra: The Cycle of Becoming

Karma and dharma operate within the overarching framework of saṃsāra, the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

Saṃsāra is not simply punishment or repetition - it is a processual field, shaped by ignorance and craving, in which beings evolve or stagnate.

1. Saṃsāra as Existential Condition

- All beings - human, animal, divine - participate in this cycle.

- No ritual privilege exempts anyone.

- Liberation is a universal challenge.

2. Saṃsāra as a Moral Feedback Loop

- Every action reinforces or weakens the conditions that sustain rebirth.

- Saṃsāra thus becomes a moral ecology.

D. Mokṣa: Liberation as Alignment, Realization, and Release

Liberation (mokṣa, nirvāṇa) unites the goals of the Upanishadic, Buddhist, and Jain traditions, though each defines it differently:

- Upanishadic thought: Realize the identity of Atman and Brahman; ignorance dissolves.

- Buddhism: Realize non-self (anātman) and the dependent arising of all things; craving ends.

- Jainism: Burns away karmic matter; the soul rises purified and free.

Yet beneath these differences lies a common intuition:

- Liberation is achieved not through external action but through inner transformation.

- It is the culmination of ethical conduct, meditative insight, and freedom from attachment.

Mokṣa is not escape but alignment -- the restoration of being to its authentic mode,

- the resolution of suffering,

- the ending of ignorance,

- the realization of truth.

E. A Moral Universe: India’s Axial ContributionThe maturation of karma–dharma metaphysics created an entirely new cosmology:

- The universe is ethically structured.

- Action and intention shape destiny.

- Liberation is a universal possibility.

- Responsibility is intrinsic to existence.

- Consciousness is the key to transformation.

This is India’s distinctive contribution to the Axial Age:

a universe where ethics, metaphysics, and the evolution

of consciousness are inseparable.

In this world-cosmic perspective, the path to liberation is not appeasement or ritual performance, but participation in the moral and metaphysical process that underlies all becoming.

V. The Birth of Interior Liberation: India’s Axial Achievement

By the end of the Axial Age, India had produced one of the most sophisticated spiritual-philosophical systems in world history: a vision in which liberation is not gained through divine favor, priestly mediation, or ritual precision, but through inner transformation, ethical clarity, and experiential insight. This shift represents a radical reorientation of religious meaning - one which would shape Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and later global contemplative traditions.

India’s Axial achievement can be summarized in three intertwined realizations:

- that consciousness lies at the heart of human experience,

- that ethical intentionality shapes the trajectory of existence,

- and that liberation requires the reconfiguration of the self’s relationship to reality.

A. From Outer Control to Inner Mastery

Early Vedic religion assumed that the world could be managed from the outside - through ritual, sacrifice, and cosmic maintenance.

The Axial revolution inverted this paradigm.

Human beings discovered that the sources of suffering and ignorance lay not in the displeasure of gods or in cosmic disorder, but in the mind’s own attachments, illusions, and misperceptions. Thus spiritual transformation became an interior project:

- overcoming ignorance (avidyā),

- quieting craving (tṛṣṇā),

- refining perception (viveka),

- cultivating nonviolence and compassion,

- and recognizing the deeper nature of reality.

This movement from outer control to inner mastery is one of India’s most enduring contributions to human culture.

B. Knowledge, Discipline, and the Liberation of Consciousness

The interior turn produced a rich ecology of practices aimed at awakening one's soul or inner being:

- meditation (dhyāna),

- self-inquiry (ātma-vicāra),

- ethical restraint (yama–niyama),

- renunciation (saṃnyāsa),

- mindfulness and insight (smṛti–vipassanā),

- ascetic purification and austerity,

- contemplative realization (samādhi).

The Upanishads linked liberation to knowledge (jñāna).

The Buddha linked it to transformative insight (prajñā).

Jainism linked it to the purification of karmic bondage.

But all agreed:

- Liberation requires a transformation of consciousness.

- Not belief, not doctrine, not ritual performance

- But a fundamental re-seeing of the nature of self and reality.

C. Ethics as Spiritual Power

Perhaps India’s most profound contribution to the global religious imagination is the union of ethics and metaphysics.

In the mature Axial worldview:

- Right action is not merely moral - it is ontological.

- Ethical conduct aligns the self with the deep structure of reality.

- Nonviolence (ahiṃsā) becomes a metaphysical principle.

- Compassion becomes a method for dissolving suffering.

- Truthfulness, restraint, humility, and generosity become forces that reshape consciousness.

Here ethics is not an accessory to spirituality; it is the engine of transformation. Great spiritual power derives from great moral clarity.

D. Universality and the Democratization of Liberation

India’s Axial movements broke open a path that transcended caste, status, and birth.

Liberation became available to:

- householders and renouncers,

- kings and merchants,

- women and men,

- priests and wanderers,

- the wealthy and the poor.

Buddhism and Jainism explicitly rejected caste privilege, while Hindu traditions gradually incorporated renunciation and meditation into household life.

This democratization of spiritual life marks one of the great humanitarian achievements of world religions.

E. A New Vision of the Human Condition

By the close of the Axial Age, India offered a coherent, integrated view of human life:

- The self is not fully what it seems.

- Suffering has identifiable causes.

- Action carries moral weight across lifetimes.

- Consciousness is the medium of transformation.

- Ethics, meditation, and insight can free beings from the cycle of rebirth.

- Liberation is the deepest possibility of human existence.

This interior vision gave Indian civilization a philosophical and spiritual depth unparalleled in the ancient world.

It is no exaggeration to say that India’s Axial Age marked the birthplace of global contemplative philosophy - a tradition that continues to influence spiritual seekers, philosophers, neuroscientists, and theologians today.

Section V Summary

India’s Axial revolution shifted the locus of religion from outer ritual to inner transformation, from cosmic maintenance to metaphysical insight, from priestly hierarchy to universal accessibility. Through the Upanishads teachings, Buddhism, Jainism, and related renouncer movements, India articulated a world in which liberation is a matter of consciousness, ethics, and existential clarity - thus completing its distinct and enduring contribution to humanity’s spiritual development.