(Metamodern) Process Radical Theology

v. Secular/Humanistic Radical Theology

I may develop this topic a bit more in the days ahead. For now I'd like to begin here with these thoughts and in separate posts review (and possibly add to) the links I've listed below along with visuals and perhaps a video or two.

Examining the Past... Dogmatic Religion Was Not For Me

I began my journey away from a secularized form of evangelical theology probably in my 30s and began writing of a new way of doing Christianity less than a dozen years ago. It came when joining an emergent Christian church which is simply an assembly of evangelical Christians more focused on loving ministries to those around themselves than on traditional ministries focused on dogma over people.

I was raised in the religiously stricter traditions of Christian fundamentalism and conservative Evangelicalism which had outreach ministries for the purposes of helps and indoctrination. Whereas the emergent church I joined many years later carried many of its evangelical beliefs with it but was less interested in indoctrination and more interested in serving others irrespective of standardized tests of church dogma.

Later, my past fellowships generally became stricter over the years in their outlooks towards society - not only condemning sin and evil but building higher gates and walls around itself as theocratic islands of refuge for traditional orthodox Christianity protecting itself from ubiquitous sins and evils. These latter movements of worldly fear and the desire to control the uncontrollable fed upon itself paradoxically creating in its wake a more "secularized" church mindset of "them vs us" rather than a loving mindset to those outside it's approved bastions of faith.

Quickly, church-approved Christian colleges and secondary educational schools rose up; political "woke-ness" became a thing; socio-political tests for the "right kind of Christian beliefs" settled within the hallowed halls of evangelical Christianity; and ministries to society fell by the wayside as Christian White Supremacy and Trumpian National Populism took over as the new gospel of Jesus. Where churches once reached out to the homeless, the sick, the unwanted and overlooked, they now had fallen into the politics and secularization of the day where compassion comes last and self-survival of religious purity comes first.

Which meant that while all this was going on I had the good fortune to begin attending an emergent church which followed Jesus' commands to love over all the things which can get in the way of following Jesus. It also showed to me how my earlier fellowships had wandered away from their first love and had gotten lost in the weeds of i) Christian protectionism; ii) Church religious rule and dominionism over America's Constitutional civil democratic laws for all; iii) Sloganeering for the defense of a righteous and legalistic Christian faith; and, iv) Defining Christianity in terms of political party distinguishing whether you were a godless "liberal" democrat or a true believing, home-schooling, critical-racism rejecting, "trumpian" republican.

Leaving My Past Behind... Becoming a "Done" but not a "None"

Hence, in these matters, I don't believe I left my former faith as my former faith had left me.... As I aged and learned to read and interact with people and society beyond my church groups I became aware of a type of Christian faith I was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with... one which would demand of me a "Berean" kind of re-examination regarding my Christian faith's pros and cons....

I began by deconstructing my faith under the assumed blogger name of "Skinhead" denouncing and burning up all the chaff I held in my ungod-like faith and the fellowships I clung to. Beginning with Jerry Falwell and the Kingdom ministries of tele-evangelism; the spread of proper "bible" colleges and home schooling programs one must attend in order to have a "godly" biblical education; and the many socially approved attendances, thoughts, ideas, and behaviors to observe to maintain a "Christian" faith. I felt a deep sense of relief when letting go - if not a refreshing spiritual weight lifting off my soul when abandoning the mere act of judging others, or learning to see people as people rather than as "they should be." In God's world there is a beautiful, complex array of difference-and-movement amongst humanity as there is in nature. Learning to see it for what it was became the best gift the Lord could have given me when rethinking what a faith in a loving God meant. It meant a deeply vibrant restoration, if not redemption, from a faith caught up in the wrong things.

After six months of deconstructing my faith this activity gave way to rebuilding... or re-constructing... my Christian faith which eventually gave way to a variety of permutations from my past Baptist traditions (GARB/ABWE). Generally, I kept what I could of my past biblical training and earlier fellowships while renouncing all forms of biblicism, Calvinism, and judgmentalism and began a long return to my Baptist roots of historic Arminianism which I quickly updated into Open and Relational Process Theologies of uncontrolling divine love, indeterminant freewill agency, and culturally progressive attitudes willing to re-educate its faith and faith practices.

As example, when reading the bible, it helped to read it literarily rather than literally. That is, to read the bible with attention to it's grammatical, historical, and contextual study of ancient cultures. But not "inerrantly" when applying a literalistic study of the bible's passages as is being taught by evangelically-minded churches, schools, and colleges. A literal exegesis --> exposition --> eisigesis but warrants unloving religious cultural norms more willing to uplift "holiness" over "loving" one another.

Too, the first six to eight years of my postings here at Relevancy22 speak to the disquiet my soul was undergoing in it's journey through so many defeating situations. In them I began the difficult labor of creating a new theological foundation for Christianity of every flavor and denominational belief. This consisted in several objectives:

1 - To be willing to unlearn in order to relearn.

2 - To utilize doubt and uncertainty as better measures of writing a theology than thinking there could only be but one way of doing this task.

3 - To remove the Westernization of the bible (sic, Greek Hellenism et al) for a more organic and comprehensive metaphysic which I found in Whiteheadian Process Philosophy and Theology (ala John Cobb and company) as a better foundation to write of God, faith, and creation.

4 - And lastly, to expand this Process Thought into every area of science, belief, and academic by interweaving and integrating all areas towards an organic, relational theology and cosmogeny fraught in cooperative vs. competing partnerships, brokenness, and regeneration.

5 - This took some years to do and is where I am today but my faith journey's overall effort was to re-sync the Christian faith so that Jesus and God's love came together and became the new center of my Christian faith and theology.

When doing so I wished to rebalance the books on the Person and Work of God... to re-right Christian doctrines and dogmas towards a God who loves always. When doing so I can now more easily speak to both church and world whether on the bible, faith, practice, science, politics, economy, eco-civilizations, environmentalism, and so on. My earlier church doctrines and beliefs could not speak so eloquently nor so easily as I can now. But a theology whose center is Love and whose foundation is processual makes all the difference.

And so, I have learned to talk about my faith again from a far more positive and expanded (doctrinal) foundation than the crumbling, dying one I had left behind. My many years of lay ministry, teaching, pastoring, evangelizing, and outreach ministries, besides that of a Bible College B.A. and a three year M.Div. seminary training, helped towards this complex process as much as it hindered it....

But the Lord gifted me with the ability and passion to write my journey down, which I did, with a lot of help by the Lord's Spirit in discerning the many "spirits" blinding me to the pathways I needed to be trekking. Both church and world "spirits" which misdirected and confused the real problems at hand; attitudes and beliefs which attempted too many times to lead away from the Jesus I needed to see the more clearly over the dross and chaff lying everywhere about my heart, head and soul.

Two kinds of Radical Theology... One with Jesus, the Other Without Jesus

I say all of this to introduce a new Process-Relational version of Radical Theology as versus the more common agnostic forms of Radical (Humanistic) Theology. They each use the same moniker "radical theology" but they each go in their separate directions having first met on the common ground of personal, familial, community, and societal deconstruction and reconstruction.

Radical theology as a discipline, first began with the "death of God" rubric under the pen of J.J. Altizer which frankly, was a legitimate assessment before, during and after World War II. It is certainly a subject which I should write more about as we so often travel the hard roads of life which ruin us, tear us apart, and make us so very angry.

For many, many reasons we each experience the loss of faith - or, the death of God - in our lives. And for many other reasons we may sometimes be able to get past the deadness in our souls of God's failure to help when we needed it most.

But when I think of God's existential death due to harmful phenomenological human experiences it doesn't mean God has died but that this God has died for me in my heart and soul. The things we cherish were removed from us and cannot be gotten back. This loss has left real anger or sadness or hurts which God could not protect us from. In this way God has died like a dear friendship lost to us forever.

But the process-version of radical theology always comes back to the God who loves us and asks "Why?" It may never get answers. It may only get the barren landscapes of learning to live with loss. And yet, God is there healing and helping as possible. We live in a God-created world but not one devoid of sin nor evil. It has its beauties and satisfactions but it also has hardship and hurt. A theology of Love says that God is always with us, loving us but with a freewill creation comes indeterminant joys and sadness God cannot protect us from but can help us perhaps survive and get through with a measure of joy and assurance where none should be expected.

But the secular-version of radical theology speaks to a God who isn't God but only a "symbolic signifier" of our religious psycho-social identity. An identity bound up in resulting socio-religious mores, beliefs, attitudes, and deeds. which finally says, "Yes, God is dead. God never was, and it was I which held on to this misplaced belief."

Now perhaps for some radical theologians writing of our common psycho-social identity known in their parlance as a religious or iconic signifier of a symbolic God who isn't but is upheld by our social circles of family and church... perhaps for some radical theologians this "God who isn't" is but the beginning of their own journey (as well as their readers) towards discovering the "God who is"... who may become their own divine Signifier.... And yet, for many who are utilizing this kind of philosophic radical theology God is simply a descriptive label filled with personal content and not supernatural reality.

Which is why I think of radical theology in two forms - one which keeps God and rethinks its faith; and one which shelves God for a secularistic treatise of religion. I found the same thing to be true when taking a class with Alain Badiou a few years back when discussing the topic of "Being and Event." Except for his philosophic outcome it was the same as the gospel of Jesus but without Jesus. It perfectly explained the processes between being and event. So too with radical theologians. They can perfectly speak to their subject but in the end God becomes signifier rather than Signifier. I chose the latter while not neglecting to be conversant with the former as time and studies allow.

Conclusion

For myself, like many process theologians, when we speaking to radical theology we are also using the language of deconstruction and reconstruction but this language is never without the Creator God of Redemption as a real, divine Personage and Being. And when rebuilding the Christian faith we will always return to the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in newer-and-fuller valuative meanings towards the many processual forms that divine atoning redemption and generative healing may take. (Christian) Radical theology used in this religious sense retains God, and looks to God, for salvation in the many ways which divine salvation may take.

And so, for every Peter Rollins out there, there will be his counterpart of Rob Bell re divine angst and reunion. For every Maria Francesca French (nee Grassi?) there will always be a Grace-Ji-Sun Kim re intersectional feminism and liberation theology. For every Jack Caputo there will be a John Cobb (a Whiteheadian process theologian) re divine absence and presence.

Each of these names are dear to me and their work important to read, know and understand. But each speaks to the radicalness of divine presence using their own philosophical-theological backgrounds even as they each, like all metaphysical travellers, are exploring life's alternatives to personal identity and faith by their own separate routes of examination.

My paths, as they have presently taken me, will continue along the lines of expanding process faith studies, worship, and bible exposition using the Christian faith's own hoary commentaries and long histories of words and deeds when examining what Christians have done right, and what they have done wrong, and might do better with a more loving version of their theologies.

Come join me and let's journey this faith-process together...

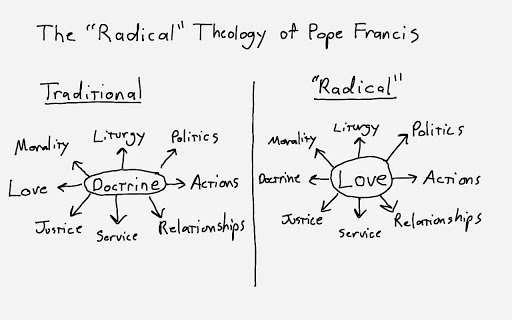

And finally, with Pope Francis, the best radical theology I can think of is by placing the love of God at the center of my faith and not the dogmas of the church at faith's altar. "Where rules mislead, grace prevails."

Amen and Amen,

R.E. Slater

February 8, 2023

edited, Feb 9-10, 2023

ChatBot and I Discuss Radical Theology

ME:

Hi Chatbot

CB:

Hello! How can I help you today?

ME:

Compare the radical theologies of Peter Rollins, Jack Caputo, and Maria Francesca French.

CB:

Peter Rollins, John Caputo, and María Francesca Grassi are all prominent thinkers within the field of radical theology, a branch of theology that seeks to challenge and subvert traditional religious beliefs and practices.

Peter Rollins is a Northern Irish philosopher and theologian who is best known for his work on the idea of "apophatic theology," which emphasizes the limits of language and reason in expressing the nature of God. He is also known for his critiques of traditional forms of Christianity and his emphasis on the importance of doubt and questioning in the spiritual life.

John Caputo is an American philosopher and theologian who is best known for his work on postmodern theology and the philosophy of religion. He is particularly known for his critiques of traditional forms of Christianity and his emphasis on the importance of "weakness" and "vulnerability" in religious thought.

María Francesca Grassi is an Argentine philosopher and theologian who is known for her work on feminist and liberation theologies. She is particularly interested in the ways in which traditional forms of Christianity have been used to oppress marginalized communities and is committed to promoting a more inclusive and equitable form of religious thought.

In summary, each of these thinkers offers a unique perspective on the nature of theology and religion and challenges traditional forms of Christianity. While they share a commitment to subverting established beliefs and practices, their specific critiques and perspectives differ significantly.

ME:

Each [radical theologian/philosopher] critiques Christianity for its lack of humanity towards others; it's devotion for [religious] rules over loving one's neighbor; and [the church's seeming] desire to oppress all those who disagree with traditional Christianity. Can one say that radical theology is a form of removing loveless religion from Christianity's secularization faith?

CB:

Yes, one could argue that radical theology can be seen as a form of removing loveless religion from Christianity by critiquing the ways in which traditional forms of Christianity have been used to oppress marginalized communities and promote inequality.

Radical theologians like Peter Rollins, John Caputo, and María Francesca Grassi are often critical of the prioritization of doctrine over compassion and the lack of concern for the well-being of others in traditional forms of Christianity. They argue that this type of religion, which they see as "loveless," needs to be transformed or rejected in favor of a more humane and compassionate form of faith.

In this sense, radical theology can be seen as a response to the secularization of religion, which is often characterized by the decline of traditional religious beliefs and practices and the increasing influence of secular values and ideals.

By challenging the dominant forms of Christianity and promoting a more loving and inclusive faith, radical theologians aim to reclaim the religious impulse from secularization and to reorient Christianity towards a more humanistic and compassionate path.

ME:

Whitehead's Process philosophy as basis for process theology ala John Cobb, Thomas Oord, Tripp Fuller, etc, also offers the same critique of Christianity as its non-processual counterpart of radical theology. Between the two, which is more theistic in orientation (as versus institutionalized criticism)?

CB:

Whitehead's process philosophy and process theology both offer critiques of traditional forms of Christianity and emphasize the importance of process and change in religious thought. However, process theology, as embodied in the work of John Cobb, Thomas Oord, Tripp Fuller, and others, is generally considered to be more theistic in orientation, as it seeks to affirm the existence and ongoing activity of God within the world and human experience.

In contrast, radical theology, as represented by thinkers like Peter Rollins, John Caputo, and María Francesca Grassi, tends to take a more institutional critique of Christianity and focuses on the ways in which traditional forms of religion have been used to oppress marginalized communities and promote inequality. Radical theologians are often more skeptical of traditional beliefs about God and the supernatural, and their work can be seen as more critical and deconstructive in nature.

So, in terms of theism, process theology is generally considered to be more theistic in orientation, as it affirms the existence and activity of God within the world, while radical theology tends to take a more critical stance towards traditional beliefs about God and the supernatural.

ME:

Agreed. One is theistically oriented with outcomes of removing dogmas for humanitarian purpose while the other is more agnostic with similar outcomes of demystifying faith for fairer and equal freedoms of the individual.

CB:

Yes, that is a fair characterization. Process theology is theistically oriented and seeks to reinterpret traditional beliefs about God in a way that is more consistent with contemporary scientific and philosophical understandings, while also emphasizing the importance of compassion and social justice. Radical theology, on the other hand, is often more agnostic in orientation and critiques the ways in which traditional religious institutions and beliefs have been used to oppress marginalized communities and promote inequality. Both approaches aim to demystify traditional religious beliefs and practices and to promote a more humane and equitable form of faith.

ME:

Thx. All for now. G'night

CB:

You're welcome! If you have any more questions, feel free to ask. Have a great night!"

REFERENCES TO READ

Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology (Paperback)

Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology (Paperback) Process Theology (Paperback)

Process Theology (Paperback) On the Mystery: Discerning Divinity in Process (Paperback)

On the Mystery: Discerning Divinity in Process (Paperback) Process Theology: A Guide for the Perplexed (Paperback)

Process Theology: A Guide for the Perplexed (Paperback) God Christ Church: A Practical Guide to Process Theology (Paperback)

God Christ Church: A Practical Guide to Process Theology (Paperback) A Christian Natural Theology: Based on the Thought of Alfred North Whitehead (Paperback)

A Christian Natural Theology: Based on the Thought of Alfred North Whitehead (Paperback) Piglet's Process: Process Theology for All God's Children (Kindle Edition)

Piglet's Process: Process Theology for All God's Children (Kindle Edition) Cloud of the Impossible: Negative Theology and Planetary Entanglement (Paperback)

Cloud of the Impossible: Negative Theology and Planetary Entanglement (Paperback) God as Poet of the World: Exploring Process Theologies (Paperback)

God as Poet of the World: Exploring Process Theologies (Paperback) Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes (Paperback)

Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes (Paperback) Back To Darwin: A Richer Account of Evolution (Paperback)

Back To Darwin: A Richer Account of Evolution (Paperback) The Process Perspective: Frequently Asked Questions about Process Theology (Paperback)

The Process Perspective: Frequently Asked Questions about Process Theology (Paperback) Creative Evolution (Paperback)

Creative Evolution (Paperback) God of Becoming and Relationship: The Dynamic Nature of Process Theology (Hardcover)

God of Becoming and Relationship: The Dynamic Nature of Process Theology (Hardcover) Matters of Life and Death (Paperback)

Matters of Life and Death (Paperback) Adventures of Ideas (Paperback)

Adventures of Ideas (Paperback) Process Theology: A Basic Introduction (Paperback)

Process Theology: A Basic Introduction (Paperback) In God's Presence (Paperback)

In God's Presence (Paperback) The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event (Paperback)

The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event (Paperback) The Nature of Love: A Theology (Paperback)

The Nature of Love: A Theology (Paperback) Grace & Responsibility: A Wesleyan Theology for Today (Paperback)

Grace & Responsibility: A Wesleyan Theology for Today (Paperback) Fall to Violence: Original Sin in Relational Theology (Paperback)

Fall to Violence: Original Sin in Relational Theology (Paperback) Religion in the Making (Paperback)

Religion in the Making (Paperback) Science and the Modern World (Paperback)

Science and the Modern World (Paperback) Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming (Paperback)

Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming (Paperback) Aquinas To Whitehead: Seven Centuries Of Metaphysics Of Religion (Hardcover)

Aquinas To Whitehead: Seven Centuries Of Metaphysics Of Religion (Hardcover) Process-Relational Philosophy: An Introduction to Alfred North Whitehead (Paperback)

Process-Relational Philosophy: An Introduction to Alfred North Whitehead (Paperback) Creating Women's Theology: A Movement Engaging Process Thought (Paperback)

Creating Women's Theology: A Movement Engaging Process Thought (Paperback) Becoming a Thinking Christian: If We Want Church Renewal, We Will Have to Renew Thinking in the Church (Paperback)

Becoming a Thinking Christian: If We Want Church Renewal, We Will Have to Renew Thinking in the Church (Paperback) The Divine Relativity: A Social Conception of God (Paperback)

The Divine Relativity: A Social Conception of God (Paperback) Process Theology and Celtic Wisdom (Paperback)

Process Theology and Celtic Wisdom (Paperback) Beyond the Impasse (Paperback)

Beyond the Impasse (Paperback) Praying with Process Theology: Spiritual Practices for Personal and Planetary Healing (Paperback)

Praying with Process Theology: Spiritual Practices for Personal and Planetary Healing (Paperback) Gilkey on Tillich (Hardcover)

Gilkey on Tillich (Hardcover) Augustine's Theology of Angels (Hardcover)

Augustine's Theology of Angels (Hardcover) Religious Experience and Process Theology: The Pastoral Implications of A Major Modern Movement (Hardcover)

Religious Experience and Process Theology: The Pastoral Implications of A Major Modern Movement (Hardcover) Science and the Search for God: Spirituality for the Twenty First Century (Kindle Edition)

Science and the Search for God: Spirituality for the Twenty First Century (Kindle Edition) The Creative Mind (Paperback)

The Creative Mind (Paperback) Living Consciousness: The Metaphysical Vision of Henri Bergson (Hardcover)

Living Consciousness: The Metaphysical Vision of Henri Bergson (Hardcover) Dreams (Kindle Edition)

Dreams (Kindle Edition) Matter and Memory (Paperback)

Matter and Memory (Paperback) An Introduction to Metaphysics (Paperback)

An Introduction to Metaphysics (Paperback) Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (Paperback)

Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (Paperback) Thinking in Time: An Introduction to Henri Bergson (Paperback)

Thinking in Time: An Introduction to Henri Bergson (Paperback) The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Paperback)

The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Paperback) Time and Free Will (Paperback)

Time and Free Will (Paperback) Henri Bergson: Key Writings (Athlone Contemporary European Thinkers)

Henri Bergson: Key Writings (Athlone Contemporary European Thinkers) Salvation: Jesus's Mission and Ours (Kindle Edition)

Salvation: Jesus's Mission and Ours (Kindle Edition) The Message Devotional Bible: Featuring Notes and Reflections from Eugene H. Peterson (Hardcover)

The Message Devotional Bible: Featuring Notes and Reflections from Eugene H. Peterson (Hardcover) As Kingfishers Catch Fire: A Conversation on the Ways of God Formed by the Words of God (Hardcover)

As Kingfishers Catch Fire: A Conversation on the Ways of God Formed by the Words of God (Hardcover)