|

| Amazon Link |

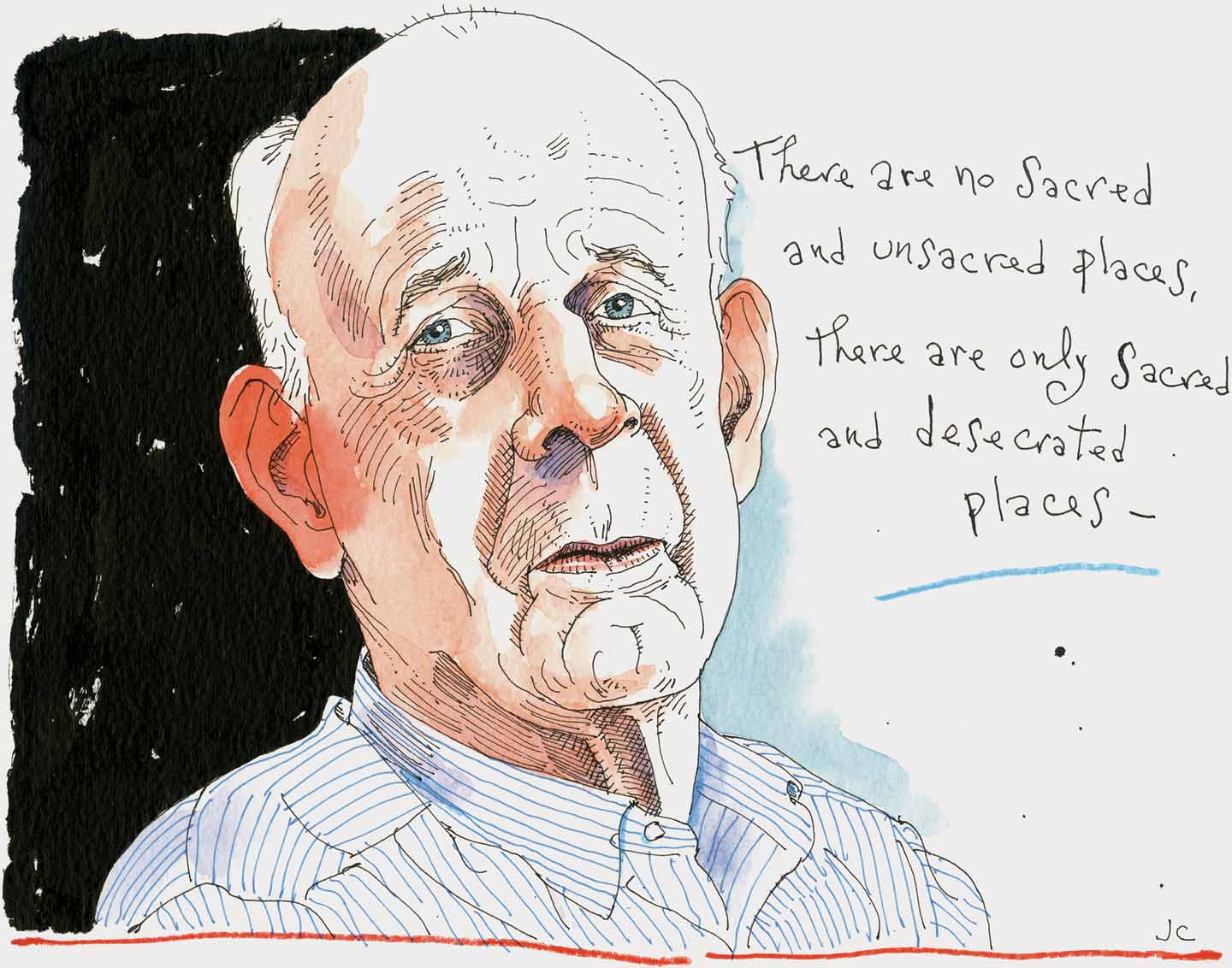

"Here is a human being speaking with calm and sanity out of the wilderness. We would do well to hear him." —The Washington Post Book WorldThe Art of the Commonplace gathers twenty essays by Wendell Berry that offer an agrarian alternative to our dominant urban culture. Grouped around five themes—an agrarian critique of culture, agrarian fundamentals, agrarian economics, agrarian religion, and geobiography—these essays promote a clearly defined and compelling vision important to all people dissatisfied with the stress, anxiety, disease, and destructiveness of contemporary American culture.Why is agriculture becoming culturally irrelevant, and at what cost? What are the forces of social disintegration and how might they be reversed? How might men and women live together in ways that benefit both? And, how does the corporate takeover of social institutions and economic practices contribute to the destruction of human and natural environments?Through his staunch support of local economies, his defense of farming communities, and his call for family integrity, Berry emerges as the champion of responsibilities and priorities that serve the health, vitality and happiness of the whole community of creation.

- Week 1 - 9/9: "A Native Hill," "The Unsettling of America," "Feminism, the Body, and the Machine," "Think Little"

- Week 2 - 9/16: "The Body and the Earth," "Men and Women in Search of Common Ground," "Health is Membership," "People, Land, and Community"

- Week 3 - 9/23: "Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community," "Conservation and Local Economy," "Economy and Pleasure," "Two Economies," "The Whole Horse"

- Week 4 - 9/30: "The Idea of a Local Economy," "Solving for Pattern," "The Gift of the Good Land," "Christianity and the Survival of Creation," "The Pleasures of Eating"

* * * * * * * * *

1.1

Unknown 0:00

Thank you everybody for coming to this, I'm not sure if I should look at the

screen or at everybody, or there's many screens to look at here, this is kind

of like a 12 year old kids dream dream room right if you had like video games

hooked up and so on but then there is an irony that was brought up right away

that we're talking about, you know what, one of the source texts are one of the

essays here was his essay Why Why I'm not going to own a computer but we'll

talk about that a little bit. And I even make mention of that because I know

we'd be on computers talking about this and especially for online guests. I

think Wendell might give a little space of like a thumbs up that we're able to

talk about these things meaningfully across boundaries using a computer at

this, at least I'm assuming I'm not going to ask him personally, I'm just going

to make that assumption. So it's really great to be back with the call program

I really love doing it, so far for me it's been all Wendell Berry since I

started doing call, so I was able to do Windows fiction, teaching through a set

of a short stories, a couple of autumns ago. And then this summer, got involved

over Zoom, zoom with Wendell Berry's poetry, which was great. Also, I think I

was sitting in my basement hiding out at that time so it's good to be here. And

it's great to have people coming in on line, it's great to see people in

person. And so, here we go to one of the various essays, I think I made

mentioned, we, my colleague Matt Bonzo and I teach together at Cornerstone for

25 years. We wrote a book about Wendell Berry that was published in 2008 from

the precise stress paper publishing, which was one of our in the cultivation of

life we had a totally different title, and then the publishing the publisher.

One thing I found out was, you don't get to pick your title, or your cover and

the publisher said we're putting Wendell Berry's name in the very beginning of

the title, your names are not really that powerful, his address. Okay, that's

what everyone that one of the things we've done a little book tour out to

Pennsylvania and so whatever a book tour might be a very small book tour, and

we were often asked, Well where would you start reading the various words in

it. We found ourselves often saying, Go to the fiction or to the poetry because

if you go to the essays, he might seem really grouchy, right and he might You

might catch him in a tone or in a mood or on a topic, where he'll step on your

toes right. Not that that doesn't happen at times in the verse, as we found

out, we're in the fiction, but it's certainly, you know, and that's maybe the

nature of genre study that to go to kind of a fictional universe or go to a

poetic sort of sensibility is a lot different than going to an argument. But these

essays or arguments, and there's, there's no way. There's no way around that

and but I think they share, like all of his other writing the lyrical nature,

the command of language. And really, what comes through here is the tremendous

lucid mind of this, this man, I've got to meet him several times and spend time

with him and sit and talk with him. He reminds me if you ever had a grumpy

grandpa farmer who's kind of grumpy you kind of scared of him like a grandpa

farmer who works really hard, who's also the most well read, and intellectually

sharp person that you know, combined in one person, very intimidated to talk

with him, and I'm a grown up and I'm still kind of like oh, and then there's a

little bit of odd in that. But, so this is going to, we're going to we're going

to see him in argument mode, that was a charitable argument. I will always make

that I always make that claim he argues charitably. And he's, he's, logical,

without becoming an rationalist, I think, and so let's see if we can start to sort

that out as we go through these essays and we picked a very deliberate set of

essays. So, we get him in a certain vein of mind about the agrarian issues

right which is very close to his heart. I just had something I wrote out here

that we say the books of essays, but these actually had a lot of different

forums, many of the things we're going to read were either speeches, or

magazine articles, I made mentioned here, love, and dilemma good house which is

ultimately good house which is where native Hill comes from the first one we're

going to talk about 1969, for purposes of disclosure that was here I was born.

So I'm just, I always think what was wonderful during the year I was born, he

was already fully fledged in this a couple of the things in that book are

actually speeches he gave at University of Kentucky, against the war in

Vietnam, and in defense of a guy who had protested being drafted. So there were

some speeches in there. There were magazine articles there. He has written for

a number of magazines, some of my favorite are he's written for Rodale is

Organic Gardening magazine imagine picking that up in the 70s and there's a

Winterberry article in there like an organic gardening. He's written for draft

horse quarterly that's probably the best, you know, and he's for years as

farmed with draft horses.

Unknown 4:55

I'm not sure whoever subscribes to draft horse quarterly really knows what

they're getting into opening up to one of his, you know, I'm not sure I'm not

sure how many people subscribe to but that's a tremendous thing also Orion, a

couple magazines of the Sierra Club. So the reviews and literary magazines, the

whole earth catalog, showing some of his roots and what I would call I grew up

in around Ithaca, New York, I recall it sort of 70s early kind of hippie

organic culture at the food Co Op there, many people kind of early dreadlocks

and people who are in the Old Earth and I always think of my neighbor lady,

Sally spearmint, everything in their house when you go in there to visit kids

was like, to me, like a 12 gross things I'd never want to eat now. I wish that

was my whole everything in my kitchen is like organic things sprouted things.

Probably primitive kombucha and so I was just like, where's the hotdogs, pop in

there no hot dogs in this house, you know, now I'm just like, what, why didn't

I take advantage of that. So in the end so that throughout the 70s It's a lot

of magazine articles very very desilter and diverse. And he's arguing things as

they arise and as they come up. And then in the 80s and 90s he continues that

pattern and I give it a give the names of some of the volumes of essays you can

get your hands on. We're just going to have a sampler in this course. So, in

the 70s, a continuous harmony, essays, cultural and agricultural and then

really his, his most signature volume that kind of launched him as a public

figure and really articulated the environmental movement which was the

Unsettling of America, which again, he calls, culture and agriculture, he likes

to play those two against each other with each other. That's from 1977 that's

been reissued. And those essays. Continue and we're going to look at a few from

that volume continue to just be like holy cow this is still more relevant than

ever and that was someone do the math, 20 to 45 years ago 45 years ago. It

isn't 90s Same kind of pattern. Gift of the good land which is a volume I

really like again further essays cultural and agricultural and then home

economics 14 essays which is a volume of us teaching in my undergraduate classes

from time to time, a teaching undergrads, their short essays, not that long

until the America is really long essays they're short essays, but they're also

essays that are kind of engaging and intriguing to young people, I've often

told Wendell Berry. Do you know that there's a lot of 20 year olds who read

your writing and are just like stunned and shaken by that. And he's like, I'm

glad somebody who's listening right so and so, kind of a sort of lost touch of

my talk, but that's okay we can keep on truckin. So, and then a volume I'm

actually using in my senior capstone class for Humanities, this semester, which

I really love from 1998 is called, what are people for, I think I fell in love

with it just because the title. Were people for question mark. It's like plus

they had really great cover of some paintings of store I can remember the store

courier whoever it was now that change it to a different cover and it's like

not as engaging to me. So yeah, I've kind of lost my PowerPoint, so I'm not

sure if not fully sure where I where I am if I if I advance it. I don't know if

you can restore that and one of the slots on there. And we'll, we'll keep on

going. That's happened before. Okay, let's

Unknown 8:13

go back to the up arrow because everybody was like, Yeah, you're gonna go to

the up arrow here. I'm not sure you can hear me, which is fine, I might have to

bring questions to you go back here to that, up arrow always aim hit your

presentation, and it should pop right back up over you awesome,

Unknown 8:29

but I'll be okay Thanks sister. I need to I need. We got to make sure she's

close by, that's, that's a key element right here. So let me keep going this is

just kind of introductory. The new millennium changed things and especially the

coming of 911 and Windows 10 really changed. It's changed over the last 20

years it's interesting that we're coming right to that moment here this week.

Actually, my father in law's in New York City fireman for 35 years, matter 42

in the Bronx, he was toward the end of his career when 911 happened I still

always talking on the phone the other days, there were time that this this

anniversary especially he's just, I don't even want to be down in the city I

don't want to go down there again, can't deal with it so and he's living in

upstate New York now. So, he had just written a book in 2000 called Life is a

miracle an essay against modern superstition, which is actually one of the

first ones very books I ever saw. So I didn't know about him and mica, you

know, and until like end of graduate school into my teaching career. And it's

it's a tremendous, obviously that might not have King Lear that spoken. I think

by Gloucester when he thinks he jumped off a cliff, but he didn't he just fell

down in the field and then he gets up, and it's, it's a great it's a book

length essay. But then what happens is 911 happens and then Wendell begins to

write about what's happening culturally in a much sharper tone right everything

kind of sharpens I think I was just reading something where somebody said, is I

didn't remember the world. Yeah, the world of the 90s when it was like things

were kind of different melts, it's hard to remember a different tone than the

world we live in. So he wrote in the presence of fear three essays for a

changed world right at the end of 2001. He brought up these essays he'd written

really quickly that are actually very great moving and very. I don't know. You

got a feeling. He also feels the banks that the rest of us feels right but

wants to figure out how to how to navigate it based on this long backstory of

his understanding of the world and it was really helpful. And then there's a

full volume that's actually called citizenship papers from 2003, and then I

think one that I've also used with students of volume called The Way of

ignorance and other essays 2005, and they're more. The tone is a little sharper

edge a little dark, you know, we're dealing with things that the dysfunction

within our own culture has become even more apparent in the world at large and

I think that he, you know, it's not that they're worse essays, they're all

quite, quite good but you, you definitely feel the clouds above those essays.

And that has carried through some of his later essays now what matters

economics for renewed Commonwealth, and then his, his Jefferson Lecture he gave

in 2012, he got the award from National Dog for Humanities, called it all turns

on affection. He's put that together with some other essays and their, their,

their critiques, there they are. They're a little bit beleaguered, I guess

would be the tone, you know there's a weariness to that time. Plus he's already

into his late 70s and 80s and saying you know what, what, what has changed in

all my time of doing this, then you can look at some of his more recent, recent

volumes of essays and give you kind of that same same flavor. We're gonna read

a set that actually comes at a weird moment. Norman Where's Bo who taught for

years at Georgetown College of Kentucky. By the way, that's where Wendell

Berry's permanent papers and archive is set, it was at University of Kentucky

where he taught for a long time, and also attended. But after I believe it was

after they put together like a $17 million dollar new basketball arena, he just

became frustrated. If you're a university Kentucky basketball fan, sorry about

that that doesn't. And so he said forget it in a small liberal arts college

right Georgetown Kentucky Northwest but it was a guy who taught there for

years, the guy who was the editor of the volume were meaning put together these

agrarian essays and numbers but actually I came and saw him here in Calvin he

was established through here at Calvin maybe 1015 years ago, and he now teaches

at Duke Divinity School, and I like the tone because it's wonderful. It's the

nexus of agriculture and culture that is kind of his interesting thing right,

it's, it's being a writer and a farmer, it's talking about the land and the

people who dwell in the land right and so the agrarian essays kind of hone in

on that. So all the essays, we're going to look at were written prior to 2002

Actually, the volume was already put together before 911 happened, published in

2002. So we're looking at window of the old world the old Millennium if you

will, and it'd be interesting to maybe kind of I'm not I'm not like trolling

for another call class to look at another set of his more recent essays of the

last 20 years and the different tone but yeah so I, I'm, I'm, I'm happy with

this selection because it's a variety of essays, but they're linked closely enough,

around, look when you say culture and agriculture you can you can stretch that

pretty widely, the range of these essays goes pretty widely, you know, as we're

reading them we're like oh it's kind of it's in the same topic but kind of

going over here and going over here, so it's just enough to kind of enough

critical mass to hold it together. So we're going to get into the first four of

them.

Unknown 13:33

For our class today and see if I can advance I'm not sure if I'm supposed to

push this sideways. You can see that the coming of coming of Microsoft Teams

and so on, struck many of the older faculty members everywhere with great

trepidation and it has not left me. Okay, has not left me. It stays with me at

all times when I'm in the classroom. Thankfully you can have students crying

out to you what to do okay do this sometimes contrary contrary information. So

it's kind of an uphill, it's it's really the lead essay in that first volume

that he collected which is long legged house the lonely good house by the way,

is the shack, like the shaft. It's a little house on stilts that he has on his

property right beside the Kentucky River that he has written, everything is

written in that little building over the course of the last 55 years. It has no

electricity and no plumbing there's a little house next to it, and he stops

writing when it gets dark. So it's full of windows and there's some window

poems that you could read where the wind that he talks at length about being in

that room, you can find pictures of him wearing his coveralls from his day

farming in their writing and he always writes with a pencil and a yellow legal

pad, which is going to be a source of some controversy when we get to one of

these essays has been a little thing for that so I was gonna mention lanes

landing farm where you can write to you can write to him and he responds here,

right, right here and over at Carter letter I sent him a birthday card. Once in

a while. Every last few years, and it's like PO Box One Port Royal. So he got

the first one I guess there's not a lot of competition because he and his

family decided to move up to the pond but I just actually taught before I drove

up here, drove down the BeltLine, I just taught in my American Lit class from

Walden out by the cornerstone pond at a sufficient distance, not to get too

close because you don't have to get close to any campus pond. Right, it's not

Walden Pond where you could see 10 feet down into the Clearwater that's not the

nature of our campus pond by any means. I don't think any campus pond is that

way. But we were close enough there. My only problem was getting back up off

the ground after sitting there with students for like an hour and 15 minutes

and I needed some help to, but with Thoreau famously moved out to his not yet

completed Kevin on July 4 1845 I was interested in Windows, moved with his

family, exactly 120 years later, away from Lexington out to what would, what

had been their weekend retreat and now it was going to be their permanent

dwelling which was this farm so clearly he had that in mind, he's a great,

great fan of Thoreau's work, and he's been working from that farm in that place

ever since. So when he talks about a native Hill, he's talking particularly

about this little piece of 111 acres there along the Kentucky River in Henry

County. He, it's become part of him or he's become part of it, it's not clear

which right that's, that's kind of what rootedness has done for him. I'm just

going to toss out a couple of quotes, this is kind of going to kind of do at

this time and just see what grabs somebody's interest or somebody is like, oh

wait a minute here what Yeah, or I thought that one as well or underline that

as well. These are the ones that struck me. By no means the only important

lines in the thing, but I try to keep the kind of quotes that would carry the

themes through each of the essays. The first thing that struck me in native

Hill is this my own life is inseparable from the history of the place. It is a

complex inheritance and I have been both enriched and bewildered by it.

Interestingly, the bewilderment has many more interesting than the enrichment

to me and he actually has addressed that if you ever get a chance to read his

book from 1970 called the hidden wound, called by Alan Wolf at Yale, the greatest

book by a white American about racism, it's about it's about his grandparents

who were slave, great grandparents who own slaves on the same property, and

what it means to work land that was once worked by slaves, and your ancestors

and now is worked by you and what, and it's a, it's a tremendous he actually,

Unknown 17:38

when he was at U of Kentucky, he took a semester like a sabbatical out at

Stanford, where he had actually gone to graduate school to study, writing with

Wallace Stegner years before, and he just said he sat in the library and he

just worked on that book and just wrote every day. That book it was like the

thing he had to write about. You know what 5050 years before. This has become

an issue again in our culture, he was, he was addressing I've often pointing

people towards that book to start thinking about issues of race in America

it's, it's tremendous. That's the bewildering part, but the enriching part was

also like to be somebody who's given your whole adult life to a place and reap

the benefits of that and lived in relationship to that, I think that's what

he's after a couple of other quotes just to get it rolling. I noticed how the

his place helps him resist abstraction like let's talk about environmentalism

or whatever, he can't talk about that without talking about his farm right when

I have thought of the welfare of the earth. The problems of its health and

preservation, the care of its life. I have had this place before me, you know,

so like accident. I can't remember think locally or globally. Think globally,

act locally I think is I've totally messed up that bumper sticker, okay, maybe

there's both bumper stickers at this point, I can't think about issues of the

demise of the world without thinking about what's happening right where my feet

are standing where my house is right, right, where this field is right up

behind here, right where we have get get our food get our nourishment. And it

struck me that that was a that was a profound thing you notice these going to

lament in many cases, we've lost touch with place place could be any place, or

no place, and then maybe how well can we think about these broader issues when

they have no actual tangible bearing but are only abstractions, I was kind of

struck by that necessity of being locked in, located somewhere to be able to

make, make a statement that has that has some kind of meaning about the

broadest sort of philosophical quarrels and questions. A couple of other quotes

from this. You guys probably read a lot here when he was at NYU and told the

professor. This is how it works with with people from New York City, right, I'm

going to Kentucky you're going where you're doing work that you know it's like

we're talking about, why don't you ever do that right but why would you go pee

on the border of New Jersey. And I've often thought the people that sitting out

kind of maligning my wife's family who are city dwellers in New York City. I'm

from upstate, the country a country bumpkin. That there's a certain. They claim

the rest of the country is very parochial but there's a certain parochialism in

New York City, some people don't leave their neighborhoods, very often. Don't

leave Queens once every, you know, six months or something. Never get off Long

Island, haven't actually been to the mainland again right, and you're just like

well that's, I mean, so what do you really know about Iowa. I know you know it

exists right maybe but. So, the professor said something really interesting and

the way Wendell took it, you know, in the way you phrase it is striking, where

the guy is like you go there and you're nobody who matters will know you know

where you are, meaning no urban intellectual no urban East Coast intellectual

will will know about your work. So you won't matter anymore. So to go to the

hinterland is to basically abandon mattering. Which is an interesting kind of

take on things in common, we're all, there's probably for all of us someplace

else, even from Grand Rapids that seems like a crazy move, I'm going to the up

I'm just taking off. I'm leaving it all behind for the Porcupine Mountains.

Okay. Are you sure you want to do that. For one thing they're Packer fans up

there. Okay. Somewhere you cross the line and elegant vertical lines you can

kind of understand why. Okay, get ready for lions Pro, but you're in the

Central Time Zone over there as well it really still in Michigan, but it's also

like there's always someplace from here that just seems like you've just gone

off the map you've no one was no one's gonna care, no one's gonna hear from you

anymore. You're gonna lose your relevance and so he got that. But the irony is

that he really found everything he was looking for, only when he returned to

that place. You take a look at this, of final quote from page seven my language

after he got back home and especially when he got that farm, my language,

increased and strengthened imagine how the New York intellectual would feel

about that. Yeah, that can my rural Kentucky, my language increased in

strength. What are you talking about your labor is gonna be destroyed, right,

not just the drawl but just country language right no is better. It had a place

of purpose. It set my set my mind into the place like a live roof system. I

love that. I came to see myself is growing out of the earth like the other

native animals and plants like I'm as much part of this as the hickory tree

over there and my roots are down here, just like the crop that I just put down

in these sheep that I have over here.

Unknown 22:27

So there's a, there's a counter counter cultural obviously countercultural move

at work. This is the system again writing. Just after he really moved back to

that farm. Just after he actually makes very clear member of sat with a group

of people chatting with Wendell, and he was like, I didn't retire from the

university I quit. Just remember that not retire, I quit this but you know it's

like okay, most of us were like university teachers by the way, certainly, you

know that it's I'm, you know, I, it was me making the break from that for this

right you know it's very tough to get fired and I didn't retire. Okay, so you

can see the little bit of the move the move is you have to kind of swim against

the current culturally, this is a guy who we, we talked about him in the other

one of various sessions, if you're from rural Kentucky, granted his dad was a

lawyer right grandparents are both farmers on both sides, but his dad was a

lawyer if you ever in the fiction that's Wheeler Catlett right that's his dad,

John Barry. His dad was a lawyer, he lived in town, but lived on the farms in

the summer and on weekends, got sent away to a military High School at one

point I think he was kind of like a problem he says I was a problem student I

don't know if it's one of those things where you get, they took you out of the

school, let's say you went to military school to whatever, and he wrote, you

know, he learned he said there I learned how to rebel. Okay. He went to the

University of Kentucky but then you went to Stanford during this amazing

program, the creative writing program that Wallace Stegner began right around

the time that the Iowa Writers Workshop began I mean this, there was no such

thing as a creative writing program and the you studied while sticking with him

there was Larry McMurtry the Texan of Lonesome Dove, and the Comanche, the

Comanche and Texas Ranger novels, and Ken kz of one from the Cuckoo's Nest,

then the acid Kool Aid test and taking LSD and driving across the country. He

visited windows for many times by the way, kPZ, even though they're from pretty

different also studying there was Ernest Gaines who has been here at Calvin for

the festival faith and writing the African American writer who wrote a lesson

before dying a tremendous unbelievable novel and really great movie. They're

all there together in the late 50s It was like this amazing Nexus, and then he

got a Guggenheim Fellowship and lived in Italy in France with his young wife

came back and was teaching at NYU. You have arrived. If you're a country kid or

a Kentucky kid. You've arrived if you're teaching at NYU, you just got back

from Europe, you had a novel published when you're 26 years old. It's that that

he felt like he had to leave behind because he felt like he wasn't rooted in

that where it was a world that was just sort of drifting and kind of fabricate

your own identity right, he only found it when he got back to the hardscrabble

farm there. So that's countercultural I mean that's the move I mean that's kind

of what he's getting at right in a lot of different ways showing. That's what

reminds me of the row one of his early inspirations right, you know, that

walking around New York City wherever you know the mass of men lead lives of

quiet desperation. That's what you got to get away from. That's what he found

at the farm. Yes, I think so yeah it's gonna back and forth certainly heard him

Unknown 25:33

expressing regret about time away from him or did he like, feel like that was

important.

Unknown 25:42

I've heard him expressed regret about time away and later on in his life, like

when he, when he traveled to Ireland to his ancestral town of kachelle,

Ireland, or when he went to Peru and studied Inca farming techniques. He is

like I felt this plate get in an airplane and flying far away I felt like I was

just that was after he was already kind of rooted in the farm. Beforehand I

think it's, I mean, I take it to be everybody's got to find their journey to

the place where they belong. And in his journey, taught him that he wanted it.

I think that's you know Ted he just been okay if he's going back there right

after college, or not even going to come just gonna work the farm. It would

have been a different wouldn't have been as cool a story for us but but I think

for him he thinks it would have been a different cuz he, he knew that he wanted

he'd been offered, basically everything else that he wanted, but realize what

he really wanted was that. And so, I will become a writer but not in Greenwich

Village, right, and in the talking with the elites, but after farming in the

morning, you know, writing with my pencil and paper for like organic gardening

magazine. So, choosing to kind of step out of it completely so I don't think

there's regret in that regard I think he looks at it as these are the things

that were told to me this is what you're supposed to do, this is what it means

to go up the ladder. And I don't exactly know what is if you ever read the

fiction, it you know candy caplets relationship with his dad we there is

somewhat fraught and Wheeler is it demanding I don't know if his way stick with

his dad was his dad's a lawyer and somebody who can figure out what you're

doing and do it with your life and go and get, and I don't know if that move

on, everybody has to deal with the parental expectations or then you're on the

other side is the parent where I am now and your kids are growing up and so

what are you doing, what, what, what's your major, or is there a major there

who's this boyfriend or what's going you know so we all we all end up on that

side of things and I sense there was probably some of that within his, you

could, you can, You can kind of figure out what happened with Windows life

because the character of Andy Kevin in the fiction is him in the things that go

on with Andy Catlett seem, often to be thinly veiled experiences that he

himself has had, and then Catlett goes away to become a journalist in San

Francisco, comes back to the farm in one of the novels of Moses his arm in a

farming accident seeming to represent what he's lost by his departure and his

return or something like that and I did try not to read too much symbolism in

but when somebody sets out a character that's clearly themselves you can't you

can't really help it right. So, it seems that I found my way, I made my

pilgrimage and found my way back to this place, this place will be my

sanctuary. If you take a look. I'm going to keep on going a little bit here.

This is also from this first essay native Hill. I just, I just noted up here at

the top, along with his joy at returning came to bewilderment of what mankind

has done in the place coming back to Kentucky he became a reader of Kentucky

history, and I've read a couple of the books on Kentucky history that he talked

about or mentioned, I lived in Kentucky briefly when my dad was in the army at

Fort Campbell, Kentucky when I was like five or six years old. We lived off

base at a bolt plantation setting, I have no idea what we were doing there. My

dad has passed away I can't really ask him, I don't know why, why didn't we

live on the base, I'm not. But we lived in Kentucky and listen as a Yankee,

you're like, What am I doing here, what who are, who am I here and it was kind

of, There's a lot of tension about that. But when he got to Kentucky he

realized Kentucky exemplifies it was the first frontier right from the, from

the colonists. Kentucky is the first frontier over the mountains. So, beyond

the original colonies, it's the place where you could actually see the, the

young republic of America, how it's going to work, and he speaks of it as, as

you guys were reading along here, the early settlers of Kentucky use violence

to set up their place in the world that was one of the goats. The idea was that

when faced with abundance once it consume abundantly, an idea that has survived

to become the basis of our present economy, remember that guys just went

through and chop down every tree to build the road in burn bonfires of trees,

and it's, it's kind of like

Unknown 29:49

the smorgasbord or the feast where you are the buffet where you get all these

plates and half of them right you can't even eat the rest of it and you just

like it's got too much there's just so much there, and you haven't gone to the

dessert. Dessert place right or whatever dangerous thing that still remains

there. I think Golden Corral would be the primary example of that, the dark

side of whatever that consumptive nothing against that corporate Vegas but it's

a scary place. We only been there once. Probably for our own health, you should

visit but but briefly and rarely to that place. So it's like that but with that

set the tone Kentucky settlers going in, let's cut the road through and burn

away through there. Let's cut down all the trees that set up, that, that's

still what runs the economy, he would suggest you just consume resources

recklessly. It now we're in the age of fossil fuel. So the age of fossil fuel

as you consume recklessly until it starts to run out so and then and then you

sort of scramble okay what are we going to do now. So I think a lot of the

things that he, a lot of the things he noticed are simply observing patterns

that are the same and have been the same for several 100 years that no one's

bothered to change. Right, it's a lot easier just to roll with it until

cataclysm. And, and that's, that's one of Wendell Berry's in a lot of his

writings, just like, this is the way things have always been well hold on a

minute. Is this the way things should be. Or just the way things have always

been, we can kind of feel that a little bit in here, as he suggests, it occurs

to me it's no longer possible to imagine how this country looked in the

beginning but for the way people drove their claws into it. What was it like

everywhere in Michigan, the place got clear cut by the lumber industry, or

white pine trees all over the place, especially the northern half. If you go to

the Warren Woods state park down by Warren dunes, you can see the guy who

preserved the Eastern hardwood forest, and was told by his neighbors, he was a

lunatic. But there's like 10 acres of the old forest still remaining and it's

like what is this doing here, Hickory trees and all kinds of crazy, you know,

things that you didn't know, we're still around not that second growth for us

is okay. I'm glad we have it, but you can even imagine. The Grand River side

with Potawatomi folk in there really is it's just hard to fathom it. It's it's

been changed, changed utterly if I want to quote gates right. I don't know if a

terrible beauty was born either right or whatever has been born by that. So,

you try, you try to restore. But your work becomes work, restorative work with

both, both literally with land but also with a sense of place, you can't go

back to the past, we all know that, Right, we can't, you can't just tell the

rollback time but can you act restoratively and reductively going forward. I

think that becomes a challenge for him on his Hill on his on his little rich,

rich line set of land, he says a lot of times in that so remember how many

people farmed it recklessly and eroded the entire deck they planted up the

ridge, ridge line. Listen, I grew up in upstate New York, people farming

hillsides, going up to the, you know you have cows who stand like that their

entire lives. The dairy cows, or they stand this way right, they don't stand on

any straight ground ever. My, my brother in law, my sister have a beef cattle

farm near skinny Atlas lake. They live along the rubber the road that goes

through and then both sides he owns land and goes like that. Very scary drug

chapter by the way, you've got to be careful when you're driving tractors there

and these poor cows are just kind of like, but it's, it's, you can do things,

you know plant all that you want but land, You know, the way water runs on

land, it's not, it's, you're going to do harm, very easily, and many people

have done harm even on his own land he spoke of the harm that was done by the

people they planted before and he's trying to restore the love how it goes for

solutions and again this is, it's not all negative right so you're looking for

the positive he does, he does go for that each of the essays. There used to be

a book that was preachers have reached the level of consciousness as men have.

They must become conscious of the creation, they must learn how they fit into

it, in what its needs are and what it requires of them borrowed to pay a

terrible penalty is a striking mind to me, because we don't actually, we don't

actually have to do that in the short term, you can pull those everything in

view and just pave everything and you wouldn't see but the penalty will come eventually

right. When all the water runs off in all kinds of directions and floods things

out or whatever happens with an ill conceived housing development right or

whatever had not I'm not talking about poltergeists where they buried a tub or

a graveyard and they get haunted but just, just things you could do the land

and property. And I love the phrase, what do you make of this brace. What its

needs are and what it requires them. Suddenly flipped it on its head, like,

okay I can, what are the needs of a place and land, you can think about your

own yard.

Unknown 34:40

But what does it require of you, in one sense it doesn't require anything right

it's just going to be there and if you're like me, it just grows until the

neighbors seem to be a little banker that has been mowed lately and then mode

and then you go back out there you know it's not requiring a whole lot of

upkeep care. What is, what is our place require of us, that becomes a becomes a

question that kind of steps back right kind of cuts both ways and you're like,

Okay, wait a minute I. The word that comes to our mind as biblical echoes is

stewardship, right, that he would tend or take care of it in a way, I guess

that's one of my arguments for not putting chemicals in the lawn and Alonzo

fall and there's no, the grass is all like beans and so until I can always, I

can use the term stewardship there or I could use a term of this like

negligence, I guess. But, you know, trying to do. Trying to take care of a

place both the tangible place and the human beings, the people in that place.

You can be passive and we often can be, since I got involved in my neighborhood

association on the northeast side of Grand Rapids, you realize wow there's

11,000 people in this neighborhood association, some tiny percentage of them

actually even know each other, and we all live in like a two mile radius. Why

don't people even know each other I mean but the first step toward helping to

take care of each other is that I would know this person to know that there's a

need, rather than just knowing what their dog is and what car they drive out of

the driveway, you know, I never really haven't. So, I was struck by that and

also challenged by that that there's something required of me to be a neighbor

rather than just like living here and other people live on each side. So, I got

a lesson in no rush is out there probably so we attempted rush we attempted our

beekeeping again my oldest son has been beekeeping for a couple of years, we

got two hives this year brought up they drove him up from Florida or Georgia.

They were too vigorous. Suddenly, you couldn't go into the backyard area that

one hive especially very vigorous lots of honey but people getting stung, had

the kid mowing in his bee suit. And then my neighbor came over to me and said,

I don't think you're in, you're in keeping with the Grand Rapids ordinance

about beekeeping, by the way, I don't think there's 100 yards or 100 feet

between it I was like, I think you're right I really apologize I didn't look

around, ironically, I'm the Neighborhood Association representative but I

didn't look at the neighborhood and look at the city ordinance. So we had to

move, living beehives, right in the middle of the summer. Do not try this

unless you really have to do this okay this is, there must be a better way, but

the way that I read about and studied involves staple guns and duct tape, and

lots of angry bees. Thankfully my foot returned to its normal size and my

forehead and so on and so he also find out they can find ways inside your bee

suit, they're very crafty. I don't blame the bees, they're just protecting

their queen but, but my stewardship to the place I thought we got pollinators

in here and so on and so forth but I wasn't really starting my neighborly

relationship and it got and I usually want to be the good neighbor and we're

you know, okay we're gonna be the best neighbors and so on. I had to say to my

kids I really screwed this up. I really messed this up and, and he's angry at

us and he has a right to be. So give them a couple of gift cards to restaurant

and hope all as well right and you're not bribing them, you're just like, I'm

really sorry, and you guys go out to eat or something like that so stewardship

is, it's what's required of me is more than just my idea of things but a

thought for the broader whole people to place the future, it, it's more than

just this season or this moment right where you just shoot roundup and

everything and kill everything you had out there and so on. I've been

cultivating a large patch of poison ivy for quite some time that I've

unsuccessfully tried to fight back and I've just surrendered, surrender that

area. So, this is suggesting we live by the assumption that what was good for

us would be good for the world and this has been based on the flimsier

assumption that we can know with any certainty what was good, even for

1.2

Unknown 0:00

You know that. So, that was a bit of a frustrating claim what do you think's

behind that anybody. You felt paralyzed that reading that like where do I go

from there because I read that, I read that ignorant that we make decisions

that destroy ourselves as well as everything around us. But I thought about

some of my dietary choices, okay. You don't want to go too far down that alley,

especially if you've been involved in any kind of fast food setting recently or

on the road, going on the road to New York and back you know you're sort of

forced to eat what is available like gas stations and. So, you, you, you, your

idealism gets flooded a little bit out the window right if you're trying to and

then you're just like, and you get done and you're just like I, I feel so gross

from this road trip and when I got to detox and so on and so maybe he's right

that we really struggled to even know what's best. Start with. Oh my gosh. Just

the future of, I don't know what they have they'll have big gulps or something

like that or giant gulps. And yet, we are just going to become in our own pods

floating around. That was the ideal that had been built for them. They were

constructed around after you destroy the world we have a way for you to kind of

enjoy a long cruise, where you just interesting I was telling my students or my

kids like Don't, don't you ever speak against this cartoon movie where two

robots fell in love and I had like tears in my eyes. That's how well they

affected me to ever speak against them. It's like it's robots that are cartoons

that okay, I get that. Alright, but just you know it's the concept. I think

it's interesting what do we, what are we aiming for what is what is health

going to mean he's got a couple of he's got a great essay called Health his

membership with a community that there's no health outside of that and you find

yourself you have a meal with a bunch of people you care about and it's not

just about binge eating a ton but when you're driving through Burger King on

your own. It's just sort of I got it right and there's a whole different

experience, Is it even the same experience. It's both, putting calories in,

Burger King, especially putting calories in, but it's not really the same

experience. I did when I, when

Unknown 2:18

he is the true American pioneer permutate this in this assumption that he is

the first and the last few years and take this place with everything.

Unknown 2:27

Right. Yeah, I mean it's, there's so many I was just reading throughout today

there's so much to say about like American individualism, they can the concept

of like my freedom to do as I want, please. It's such a, such a double edged

sword. Yeah, I mean, you wouldn't want the opposite thing have no freedom, no

one's looking to move into, you know, North Korea, or something like that and

leave this culture for a different. On the other hand, it teases its way out

into such a kind of like autonomous existences, where everybody and then you

have, you know, people like who's your dog stepped into my yard and my, the way

I do my yard is the right and yours is horrible and stuff you're just like what

is going on here. You not only you're not being neighborly it's like become

enemies. So But everyone's kind of right in their own eyes, there's all kinds

of sincere Wisdom literature of the Scripture kind of our you know, echoing and

articulating that like it's still, that's still around. I think I, when the

bear is declarative but there's a humility right he starts with himself, trying

to figure it out for himself. That's his grand experiment of his life and

that's why I find it helps me because he's actually tried to live the

experiment for 50 plus years and admits that it's a failed venture in many ways

he says several times enough is this so but one of them. One of the other ones.

He's never found a way to get getting past having a pickup truck, you know like

how do you how do you get past having a vehicle and like petroleum. If you live

in the country you know the pickup truck and you got cheap or whatever and if

you're in trouble like you. I guess you could go to like an electric pickup

truck are now available. But where do you go to like zip that up, that's still

the question. So, and you could do a donkey car and so on but it's going to

take you all day to go from one place to another so that there are frustration

but at least he invents those. And we all have those, but trying to live. I

used to roast I was trying to live more deliberately I see that happening for

him and it, it compels me to think it could be done in some fashion my own

life. Yes,

Unknown 4:40

banners that are wrong. For the boulders until at some point one of them. Yes,

you might lose the swag for. Right. Individuals on

Unknown 4:54

neighborliness, sometimes you think if, depending on how things are going to

their neighbors that good fences make good neighbors might hear, depending on

how it's going or what if they have like a pit ball or something like that or

kind of nothing on pitbulls if you, as long as they're over there, but I think

it's right, it's like why, why is our only commute to work to separate

ourselves from each other. That's that seems kind of quirky and to make sure

that we don't get in each other's territory or turf. I have three teenagers

emerging into like college age adulthood, so you get a lot of feelings that

people just trying to separate themselves from you and just like get into my

space, and yet you're right you're living in my house by the way, that's my car

you're driving away but so what's going on here so anyway that's that's the

point I am in life and like, wait, wait, okay, am I not allowed to ask like,

who that guy is who you're talking to there. So that's a little bit of my story

coming up. Let's take a look here, let's jump over to some possible answers

that he offers and it's interesting that he's, he's down on religion, and yet

here Wendell Berry has a querulous relationship with Christianity. He seems to

be a confessing Christian that finds a lot of problems with Christianity,

especially as it's practiced in rural America. He calls himself a grudging

bathrobe Baptist, because his, I think his granddaughter was like youth

director at the local Baptist Church and his wife Tanya is involved there so

he, like I'll come sit in the back row and leave immediately. Okay. Often

wanting to take his walks and write his Sabet poems on Sunday morning walking

his land and writing poems instead. So that you can understand some of the

problem when you read the fiction and in the small town church has a pastor

that comes every two years and tries to get out of there as soon as possible to

get to a bigger parish right and there's no real connection, and the clergy

have nothing to do with the work of the land, and it just feels totally

displaced right you can understand. Here he says something really painful. The

Heaven bent have abused the earth thoughtlessly by inattention and their

negligence has permitted and encouraged others to abuse it deliberately is a

certain theology this world's going to burn anyway, right. So just, whatever,

it doesn't really matter, it's a heaven, you know, this is this earth is not my

home I'm just passing through, you can think of some Christian songs have a

little bit of a dualistic sort of Platonic dualism tied into the theology that

what do you eat, and he's just like to do that is to just not really

participate in the world that God gave us, which he calls the creation

persistently. You've, you've missed something and it just allows people who

don't care at all to just abuse and do whatever they want right in the church

abdicating its ruler which we've all heard that narrative and it's just like

and it's frustrating. What can God's people do about that. Then there are some

amazing things that have been done to ever go to the ASA Savile Institute's

which I think Kelvin said students their Cornerstone Desmond, and the work

that's been done.

1.3

Unknown 0:21

Testing, testing, testing, but they're all the chemicals, most of the world is

not the same as when you throw out your compost pile, it's all kinds of

vegetable waste and all kinds of crazy stuff and you dig it out at the end and

plant tomatoes leap out of it again. What's going on here. That's, that's a

mystery to us.

Unknown 0:42

That's humility but you could try to control and mechanize in, ultimately, I

mean he brings up agriculture in the in the Great Plains Midwest, the top

soils, almost been fully eradicated. For over farming erosion herbicide and

pesticide usage and so on the modes of farming. What used to be two feet of

topsoil in like Iowa or Nebraska you could put your arm down into the humerus

alone has become just a couple of inches or less than that. A lot of that

research is done by his good friend at the Land Institute of Kansas named Wes

Jackson who's, who's kind of like keeps is kind of a watchdog and Burke dog

watching industrial agriculture and it's, it's out working.

Unknown 1:25

We had a student at Cornerstone to her, her mom and dad had gone to Hope

College did like I mentioned how college here, but his or her dad got a PhD and

he was a teacher at Kansas State in agriculture. I was like holy cow well Kent

has ever heard of land. Land Institute of Kansas and she's like, don't mention

that to him, he teaches like industrial agriculture large state school that places

like a gadfly like I was like okay I'm gonna be careful who you mentioned to

him like oh you know my, so yeah, whatever, you know, so that's two different

ways to approach one life giving and one just sort of like control.

Unknown 2:00

I was interested in what he says here and this seemed to be his version of how

to approach maybe the word humility is the best word. Speaking about flowers.

It's a privilege in labor of the apprentice of creation to come with his

imagination into the unimaginable, and with his speech into the unspeakable of

what a great phrase. I'm an apprentice of creation. As a farmer.

Unknown 2:23

And I'll always be an apprentice, I'm never going to be the master.

Unknown 2:28

Voice field like that with like teacher of a teacher like poetry but I've

never, I'm not going to be eights or TSLA right I'm. I like being the

apprentice of that and just like bringing people that and trying to tinker with

it myself and learn it and and celebrate the, the mastery, but with the

creation, even more so if you think you're the Master of Creation.

Unknown 2:48

You don't understand what's really at stake in creation right, but that's,

that's not supposed to be our role is mastery.

Unknown 2:57

So, you know, it's just jumping down I'm really interested in these phrases

that seem to follow up this note, what's their proper religious humility here

so here's humility in this quote, how having a consciousness and intelligence a

human spirit. All the vaunted equipment of my race can I humble myself before a

mere mere piece of Earth, and speak myself as it's pregnant but that's what you

need to do. I'm an incredibly gifted human being. Armed with all kinds of

technology.

Unknown 3:26

How can I humble myself before topsoil, dirt, and say, I'm just gonna let you

be what you are and not screw around with you mess with you saturate you

eviscerate you to make you better.

Unknown 3:40

The best thing you can do as far as I know from growing up in dairy farming

country just just throw the manure on there. And there's the circle of life and

there's all kinds of metaphors in that right. The Circle of Life. How's it

going, yeah. So I think you can hear us, which is fine so I'm going to. Yes.

Unknown 3:55

Christina trees and bird. She said, I really love this essay because it

encourages us to treat the places that are closest to us as holy places that

require our love intending rather than places that we can exploit in some way,

is descriptions of itself as a pilgrim lovingly exploring his own acres in

Kentucky, encouraged us to do the same to become as enchanted with our own

natural spaces as Wendell is with his that's from Christie, amazing content.

Well, that's really good Christina I'm sorry I could hear those. I'd love that

notion. Okay, I mean, as I read His Sabbath poems which he's composed over the

course of like 40 years while walking around on Sundays on his property. It's a

it's a, it's a perpetual pilgrimage to his own farm. He doesn't go anywhere

else to write those poems. He just walks his farm and all seasons and I think

you're just right on it's, it's, you don't have to, that's your shrine, that's

your sanctuary, that's a place where you'll discover everything there is that

needs to be discovered about the glorious created order of things right, it's not

bad to visit Niagara Falls, which is pretty cool right or to go to the Rocky

Mountains or wherever the rain forest is not bad.

Unknown 5:08

But what there is to know your engagement with the mystery is available like

right where you are. Anyone who's walked the Kelvinator Preserve. It's like I

love this place.

Unknown 5:19

Plus if you get older, I can walk it without collapsing right with some of

these trails and so on. It's like I get halfway, how can I get well I'd be

alive and I get back.

Unknown 5:27

So that's great. I think that's right on Christina it's, it's, it's a, he's a

pilgrim, but he lives on his own. Trying right and others have pilgrimages to

here, to their to his place. And that's that's a metaphor that I've tried to

use talking to my students a lot it's like your, your life vocation is your

pilgrims yeah but you're trying to find yourself to back to a place where you

can be rooted not just wandering forever though that sounds attractive when

you're 21 it's just kind of wandering around.

Unknown 5:57

But coming back around and seeing that that reverence everywhere. I think just

jump in. I'm just gonna go I believe the next one is actually just looking at

the world is still the first essay here that tells you how it's going to go for

me. Here's the sad Unsettling of America which is the lead essay by 1977, that

sort of made him famous as the spokesperson of the kind of environmentalist, or

ecological crisis which was becoming apparent and there was the gas crisis

everyone remembers from the journal quarter that's, they kind of stretched out

Gerald Ford's 20 months in office, so he was a huge thing on the grass gas

crisis at the Ford museum, there's the disco room okay. You know, it's, he's

probably, you had to fudge it a little bit to fill that entire museum with this

brief, brief time in office, but you know that it became clear that like cheap

fuel cheap, that was, that was the first time people realize oh that's a

problem, gas isn't like 515 cents a gallon anymore. What's going on in somebody

else controls it and also we're doing, I think that was exactly the same time

that the Cuyahoga River outside Cleveland caught on fire from the chemical

catalyst port I know there's the burning River and so on, like what, wait What

is this, and Long Island to the medical wastes washing up on the shore of all

these syringes and things that have been just thrown into the Long Island Sound

right by by hospitals and you're just like you're not supposed to go swimming,

why is there a shark, no there's like needles out there.

Unknown 7:14

So that's something of America as an essay is pretty interesting because he's

talking about American history and he seems to be really down on it but then it

comes around at the end and said there's promise there.

Unknown 7:26

So it's not like a total trashing of American history, but he does say that the

settling of America was haphazard and accidentally you can read the whole first

part of it.

Unknown 7:36

A mixture of fantasy and avarice, I've read quite a bit about like, search for

trapping for trading. Early American and Canadian exploration and so on. Right.

Talk about people playing the lotto. Today, look at my are scratching up like

what are those people doing so many ventures tied in I'm into gold trying to

find the gold for you know for the Spanish and Portuguese settlements in South

and Central America, the fur trade whatever just get rich quick schemes

everywhere, with a few people saying hey this is a really nice place that we

could actually farm right, of course, the native indigenous peoples caught in

between and really ravaged by disease and all kinds of other things right

along, along the way. So, generally speaking the Unsettling of America is, is a

playful but deadly earnest phrase right, we have unsettled this place by

suddenly here.

Unknown 8:31

So the counterpoint of the native peoples now you can read a lot about sort of

Native American anthropology and it is the case that it wasn't perfect. What

happened, like in a lot of cases, native peoples everywhere right, Did some

hard to change the environment did those control burns for the bison and so on.

But generally speaking, I think, Wendell is right in saying the indigenous

peoples, at least they were forced to live in some harmony with the natural

world, they couldn't manipulate it all that much. If they despoiled it and

destroyed it, they would starve to death.

Unknown 8:58

That was never a thought for them right so the hunter gatherer lifestyle has

its perils, believe me, certainly, but it wasn't despoiling a continent, as was

the literal, it's almost unbelievable that 50 million bison got annihilated.

And that's the from Saskatchewan to Texas 50 million but except for the 10

number left or whatever. And now I think those bison herds around and so on and

you can, you can still see them but how did you do and that was just the big

creature, the biggest most obvious creature with all the other things so here's

what he says it's interesting.

Unknown 9:37

Each group in historical economic sequence seems to get absorbed by the by the

next one right as this this company like consumes itself. But then he said, and

I was struck with this because I've actually given some talks on the fur trade

that happened, especially right after Lewis and Clark Expedition and the fur

trapping for traders, or something my dad was really into the history of in the

lore of that and so I've kind of followed up on that Jedediah Smith from Afton

New York actually Bainbridge New York near where my in laws live now, was the

famous mountain man who went out to you know, discover the Great Salt Lake,

etc.

Unknown 10:11

But he says that the economy right now is not really advanced since defer

trading days and I was like, What are you talking about, that was really

exploitive right and really destructive the poor beavers didn't have much of a

chance right they got almost annihilated as well, nobody says here, the economy

is still substantially better the third trade still based on the general

concept general kinds of commercial items technology weapons ornaments

novelties and drugs, and you're just like waiting, modern economy right now.

Unknown 10:37

Yeah technology weapons we know that a lot I mean a lot that goes on

economically socio politically to sustain our economy as involved with violence,

military and otherwise novelties ornaments and drugs.

Unknown 10:51

I mean, we have this, you're talking about giving alcohol to the native peoples

and trying to like, you know, wipe them out or whatever, get them, you know,

manipulate them for different stuff. Now it's opioids. Right now it's a heroin

epidemic in rural America not in the inner cities but in rural America.

Unknown 11:07

I just talked to a girl who's my neighbor girl suddenly she's all grown up, she

got married, she's gonna have a baby, she's like I thought you were still 12

What's going on here but the kids grew up so quickly. She was an EMT her senior

husband living out in Hastings Michigan barre County.

Unknown 11:21

I was like, do you have to have the antidote for heroin overdoses I can't use

it. That's one of the most frequent things we use is that remember the name of

the drug use when somebody has an overdose of opioids or heroin you can you can

revive them. It's almost a, it's almost a scary power because people know that.

And so is afraid of using the drugs, It's like, it's like a catch 22 So, it's

not different than it was at like Fort Laramie in like 1822. Same economy of

using sort of facile things, entertaining things and zoning out things to

persuade people of, but these are what they gate straightaway they're lovely

but their life's work. For those things because I'm not watching TV or taking

drugs or things like why they can't be the same economy. And I think when I

went to a point throughout these essays it's yeah, it's the same mechanism at

work right it's just masked in different kinds of ways that people are still

getting kind of trampled underfoot by it.

Unknown 12:26

You think right here.

Unknown 12:29

The statement that I was super struck by the statement anybody else build this

one once in a while it just needs to short sentences, commercial conquest is

far more thorough than military defeat.

Unknown 12:40

Can I get you to just buy what we want and get you in a trade I don't have to,

I don't have to send an army.

Unknown 12:47

You're just totally under the yoke of the system now. Right. You'll buy into it

you will use your surrender without being told you have to surrender, you'll

just surrender, for the sake of this, this commerce probably good, you don't

need that. Maybe you're going to do harm to you long term.

Unknown 13:10

Yeah.

Unknown 13:12

Americans when it comes to get them essentially 70 Kind of like density

Unknown 13:20

dependence, which ironically they had survived with without rather for however long

you know 1000s years or hundreds of 1000s of years it's arrived without So, how

can they be necessities, they become necessities like the iPhone has become a

necessity to a 14 year old kid,

Unknown 13:36

or a 67 year old kid okay so we did we wanted to go, let's, let's just, let's

just maligned the teenagers right now and not bring it back to ourselves too

closely.

Unknown 13:43

At least we can say we're still somewhat inept with them right but the 14 year

old kid right it's right before you get a phone, and even my own students will

admit to me. Yeah, I used to read books I'd read like 100 500 page books we

read Harry Potter or whatever and read all these books, and then we got an

iPhone. I don't really read that much anymore. You spend your time, you know,

and you can read, can't remember her name is.

Unknown 14:04

Her book on reading Well, she's a professor wasn't liberty, the occurrence well

prior yeah so, and just that students don't read anymore and you just have to

assign a chapter rather than a book now I listen I taught my Russian lit

several times, your steps, you know, we have 3000 pages of reading in a

semester the students were into it and going for, I would have Erickson for

quick Calvin come up and lecture on social needs and and do his Juris Doctor

this you know Eric cynic. And no, it's I can't get him to sign up for it,

because it's the even one novel is it's Russian right the novels are 800 pages

to 1000 the short stories are 100 pages long, you got problems there. Yes,

Unknown 14:41

versus.

Unknown 14:43

No,

Unknown 14:47

I was thinking about, Perhaps.

Unknown 14:56

Perceiving or experiences and little soundbites.

Unknown 15:01

Great, that's a great and very scary connection that you've made right there

because, talk about the mystery at the top so it is a mystery of the human

mind, human intellect human imagination and so on. What if that gets sort of

just laid waste.

Unknown 15:14

And then we do it to ourselves in the name of the goods such as such as let me

let me herbicide and pesticide and completely dominate and control this corn

field which there never should have been a cornfield that was like 70,000 acres

long haul of corn right I've written, but it all is right every year.

Unknown 15:33

Likewise, what we do what we do volitionally to our own lives, just different

levels.

Unknown 15:41

So the battles you have to fight with your, with your kid and when you have

kids telling you, yeah, my life was great until you know I got a phone or

something that's like I can't think like wait, but it's like, sounds like I get

your drugs or something. Right. So that's where you do your battles and try to

kind of and then you're, then you're the parent who like doesn't do anything

for your kid you know everyone's been through that as well.

Unknown 16:01

Nobody lives like we do and no one wants to come to our house we don't have a

TV or whatever it's stupid it's boring in here and kind of like he didn't seem

to be bored when he broke it.

Unknown 16:10

So we can all talk about the trauma of raising teenagers and hold hands here at

some point or therapy session. You guys have teenage grandkids maybe and it's

like okay, at least their grandkids, it's going to next generation removed, did

you see it even amplified. Take a look here at what he also says that was

striking, there's, I think he lays out.

Unknown 16:30

I like how he lays out the terms of exploiters and nurtures. So, you know,

except because I'm my mind I'm just like, I want to okay what's, what are the

sides here, that makes sense to me. There are many exploiters trying to get

whatever they can out of things, and they're probably fewer, who want to

nurture. Right, nurturing is more boring, right, it's not as exciting, it

doesn't offer the great return on, you know, work it does, as he phrases it in

this other one here, the competence of the exporter is organization could get

you know getting everything sorted out so we can kind of figure out in the

nurture is order when I first heard that I was like what's in between

organization and order they sound similar to me and then as he as he proceeds,

a human order that is that accommodates itself, both to other order, and to

mystery and that coming back to humility and mystery. It keeps coming back up

against that right, you're just like, Okay.

Unknown 17:21

I believe that I not in full control of what's going on I see that there's

mystery here that's bad. That's a bad sign right there okay so let me get up my

while I'm talking, I'm just gonna get on my power cable here.

Unknown 17:37

Don't worry. Sonia, I also have a small extension cord I carry in old times.

Unknown 17:42

From classrooms where you can't reach the like you're here, so I'm gonna wander

behind the white truck.

Unknown 17:51

It's likely on my trip that I was in a room, we had to, we had to change our

classrooms during COVID Right, so I was teaching in the, in the music hall

Recital Hall.

Unknown 18:06

That's something I don't know maybe you know it kiss the soil is an excellent

documentary on Nick Netflix that highlights the richness of soil. Yeah. Kiss

the soil, there's, there's another one I've put along with it and I think it's

just called Seed, it's about seed saving this one kid because the soil. Okay so

it's supposed to eat a pound of dirt in your life anyway right accidentally or

whatever you might as well just go down and kiss it and just like take care of

it. And but if you're eating dirt suppose we have like a calcium deficiency or

something you want to get that checked out if you want to eat dirt. But yeah,

kiss the soil of the winter seed saving, which is something that has become a

big thing for us is trying to seed save and use the same seeds again in the

next year and so on and you know there's the place near the Arctic circle that

has many of the seats that are preserved in case there's a big Wipeout event,

it was not happy on the grocery food or whatever and there's a, there's some

other seed saving places around it's quite a, it's quite an amazing thing

because the soil yeah topsoil, to be able to make compost and turn it into

tubs, that's been the best thing, I'm not sure if that's according to Grand

Rapids city ordinances either. Maybe you should check out some of the

ordinances before my whole composting operation, but that you haven't had to

buy any soil for any garden center for like 15 years but you just figure it out

of the bottom of the thing and everything's growing it feels really good, you

know, you start to queue up circle of life, but I'm not really sure what that

songs about in The Lion King but you start to feel like you're doing something

the right way.

Unknown 19:37

Yeah, you still got to get the peach pits, we have a peach tree there's peach

pits everywhere and you got to, you know, there's like rappers in there and who

threw in the top of the can or whatever somehow if you, if you go through the

screen. There it is. It's it's topsoil, it's, it's humans it's, it's living,

worms, the better, right, the bigger the worms, the better. And it's doing

something that keeps us alive, which is growing our food.

Unknown 20:03

So it's worth kissing dirt right first because it's not dirt, soil right what's

it soil, not dirt anything like really embrace it. Now that's a great, that's a

great word. Thank you for though.

Unknown 20:13

Just go into some of Windows solutions, I think when he says here, we must I

think, be prepared to see it. Stand by the truth that the land should not be

destroyed for any reason, not even for any apparently good reason now that gets

you in trouble if you work at an institution like a college like a Calvinist,

you might say hey I don't think we should go those, all those trees or that

Grove over there to create this new thing right okay there's cost benefit

analysis. It's good to be somebody who has no power because you can protest, no

one will listen anyway you're not really going to necessary no one really cares

what I say, you know, it's when you destroy land.

Unknown 20:46

You don't get that back I think he says at Forest windows, one of the novels I

think it's at the end of Jaber crow when Troy chapter cuts down the nest egg.

The hardwood forest of 200 year old trees, is if you're going to cut those down

to sell those at the plant that with corn, you won't get that cut back for

another 200 years. So you better think long and hard before you harvest that

crop, because that's gone several lifetimes. So to think about those