I

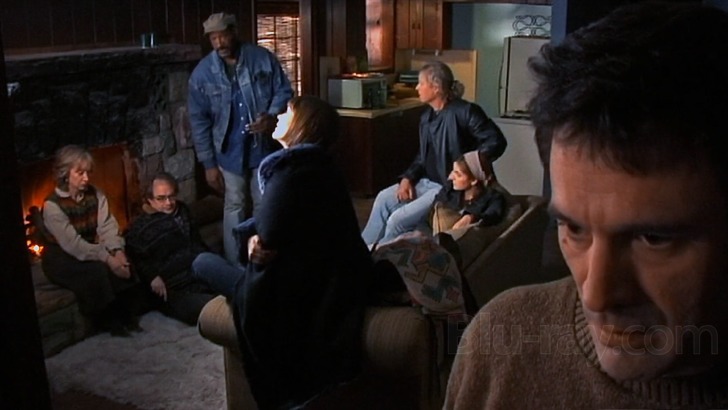

His friends from university were scholars and were gathering together that afternoon because he was leaving. Not retiring. Leaving.

As they arrived by ones and twos, no one could quite explain why the gathering felt heavier than a simple retirement, or a prolonged sabbatical, or like one of those quiet academic disappearances which happen each year.

People just leave. College offices get reassigned. New names are hung outside. Academic books remain on their shelves like fossils of remembrance.

Still, this felt different.

Inside the small cabin its owner, John, a historian by trade, stood near the latticed window, sunlight bending across the wooden floorboards. Packing boxes lay scattered around the room - some were far too light, as if their owner had learned not to carry too much, hold too much, or burden himself with unnecessary things.

“You could at least tell us where you’re going,” said Sandy, John's girlfriend, half-smiling.

“I could,” John replied from across the room, “but it wouldn’t help,” in slight foreshadowing.

Light laughter followed among his gathering friends. More sympathetic than amused... yet something in the room had begun to shift.

It felt like a liminal interior light that wanted switching on, but at that moment, couldn't. And then, there followed a small suggestion. Half wise-ass, half-serious. Starting as a joke....

II

“What if,” said John, turning thoughtfully from the window, “a man never aged?”

A few stray chuckles echoed through the empty cabin walls.

“Is this a thought experiment?” asked Dan, a field anthropologist.

“If you like.”

“Then how long are we talking?” Harry leaned eagerly forward preparing for debate.

John paused, not theatrically, but as if choosing the smallest of honest answers.

“Say, fourteen thousand years.”

Silence did not fall. It filled the room, breathlessly. A perfect beginning... and the first of several small fractures beginning to form in their final reunion.

III

“No,” Responded Dan, immediately to the statement. “This is biologically impossible.”

“Of course,” John nodded. “That’s always the first response.”

Dan folded his arms. “Fourteen thousand years ago we were still shaping flint tools. Anthropology leaves very little room for wandering immortals.”

Harry shook his head in quiet contemplation. “Cells deteriorate. DNA accumulates damage. Biology is not generous with time.”

“Is there a second?” Sandy asked.

John smiled, faintly, but tenderly.

“Sometimes.”

His friends circled him now - not physically, but intellectually. They took the bait. Their questions sharpened. Old professions rose up donning old armor. Amongst the ground was an anthropologist, a biologist, a Christian theologian, a psychologist, a historian, an archaeologist.

Each voice tried to stabilize the moment as it hungered for hypothetical sparing.

“You’re asking us to suspend everything we know,” asked Dan.

“I’m asking you to imagine it,” John said. “Not to believe it.”

“Why?” Edith asked, settling within, a bit quieter than the rest.

John looked at her differently. Seemingly peering into her wounded being.

“To see what changes.”

IV

“Say it’s true!” Harry finally spoke up. “Then what are you?”

John shrugged.

“A person who kept going. Kept living.”

“That’s not an answer!”

“It’s the only one that makes sense.”

John spoke next, not in grand declarations, but in fragments:

“Say, I experienced a winter that lasted too long. Spoke a language no one remembers. Remembered a child who died before there were names for grief?”

... Catching his breath, having stopped a moment in reflection, he continued, “I stopped keeping count after a while. Not the years, but the people who came into, and out of, my life.”

This confused his well-wishers...

“Wait! You’re saying you became different people?”

“No,” John replied. “I’m saying I couldn’t stay the same person,” as the weight of memory began adding up again.

V

Sensing John's internal burden, but not quite sure if he was up to his old parlor games of “What if?” Edith cautiously asked, “What happens when you remember too much?”

John didn’t answer right away. He let it sink into the fellowship's psyche. Let it build. Turn. Begin to grow.

“You forget differently,” he said.

“How then does that make sense?”

“You don’t lose things... they just stop becoming close.”

The room grew still. Somber. Rethinking their responses - and surprisingly, feeling more emotionally drawn in than on other occasions.

“We think memory keeps us going,” John continued. “But it doesn’t. It changes us. It rearranges what matters in life.”

Sandy quickly remarked, “And you’re not tired? You're not weary?”

John looked at her, even more tenderly than before. He stepped backed and really examined his loving friend.

“I don’t think tired is the right word.”

“Then what is?”

He searched for it. “Full, I think. Stuffed. Like I've ingested too much. Seen too much. Felt too much.” he reflectively said.

VI

At which point the proverbial pot began to come to a breaking point, as they would say.

“Ok, out with it!” Dan snapped. “You’re lying!”

“Probably,” John deferred.

“Or you're delusional!”

“Also quite possible,” continuing to play a game that was becoming all too real.

“Then why continue this charade?”

John tilted his head towards his friends.

“Because you haven’t stopped listening. You're all too willing to play this game with me.”

That landed harder amongst his skeptical friends than anything John had yet offered.

Next, Will, who had been quiet until now, finally spoke from the corner of the room. As a psychologist he had listened more than he had argued.

“Not necessarily delusional,” he said tentatively. “People sometimes construct elaborate narratives when memory and identity stretch too far apart. The mind prefers a meaningful story to an empty one.”

John studied his friend with interest.

“You think this is therapy?”

Will shrugged.

“I think it's human.”

VII

At this point, there arose a story within a story. One with many outcomes measured in hot feelings and personal outbreaks.

“Have you ever influenced history?” asked Sandy, evenhandedly, the resident archaeologist who remained more open than the others to her love's hypotheticals.

John hesitated, mulling his response.

“Not in the way you mean.”

“Try us,” she suggested.

He slowly exhaled, not for the first time wishing to bear his soul.

“There was a time,” he added slowly, “when I shared what I had learned - about kindness, about compassion, about letting go of vengeance.”

“Go on.”

“It began to be heard. To be understood, but I moved on before my words could spread. Years later I heard stories. They had grown.”

Around the room Edith’s voice could be heard trembling; she was collecting up John's strands of thought - putting them together in a way which began to move her.

“What... What are you saying…??”

“I’m saying, stories change when people need them to.”

“That’s not an answer!”

“But it’s the only one I trust,” as John kindly reflected.

VIII

The sun had shifted. The room no longer held the same light. But Edith's disturbed response lay heavily in the air. John's story had turned. It was no longer a story, it was a unwanted realization within a nest of relalizations.

No one had proven anything. No one had disproven anything. And yet, a new gravity was forming. A new reality.

Everything felt altered.

Sandy then spoke, almost reluctantly:

“John, if none of this is true… then why does it matter?”

Absent-mindedly John picked up one of his moving boxes, “Because you are all still asking the question. You're wondering if behind my words there is a new meaning unfelt in our previous relationships.”

“That’s not enough!” Art replied sharply. “Clever stories are not evidence. Universities are built on proof! Reason!”

“Yes, I think it might be,” came John's half-turned reply as he carried out a small box to his awaiting pickup outside.

IX

Pausing, at the door, John asked, “But why should we care?”

Not for effect, but as if recognizing something in their intimacy was something he had seen before.

“You don’t need fourteen thousand years,” he said.

No one moved.

“Look around you - you’re already changing. Every conversation, every loss, every moment you decide to stay or leave —” as he gestured gently around the room holding his package.

“—this is how it happens.”

Edith spoke almost to herself, not for the first time. “Maybe that’s what life is really doing to us,” she uttered.

John paused at the doorway.

“What?”

She searched for the word but never quite found it.

John smiled faintly and stepped outside.

X

John stepped out onto the cabin's gravel driveway, the door softly closing behind him.

No resolution had followed. No consensus had formed.

Inside, among the scattered boxes and lengthening evening shadows, the small community of scholars were holding quiet vigil.

Some emotion - a sense, a feeling - lingered. Not an agreement; but more like tension. A disturbance.

A suspicion that identity and meaning might be less solid than they had always assumed.

An awareness that memory is continually reshapes us as we pretend to remain the same.

That meaning is not something handed down intact, but something slowly assembling across the years. Something experienced over time.

Outside, the engine started.

While beneath the fading conversation of “What If?” a quieter question formed - one no one would say aloud:

“If life keeps changing us... why do we spend so little time noticing?”

“Why aren’t we paying attention? Perhaps learning to hold loosely the unnecessary things so that we might draw closer to the things that really matter?”

- R.E. Slater

“We imagine life as something we possess,

yet life is something we always possess, as becoming.”

- R.E. Slater

“Some conversations never end when the speaker in our head leaves -

they remain with us, quietly reshaping what we thought we knew.”

- R.E. Slater

“We rarely notice how much we are changing

until someone asks a question we cannot easily dismiss.”

- R.E. Slater

The Man from Earth

(2007)

After the Conversation

by R.E. Slater

by R.E. Slater

The door closed quietly

behind a man who kept

behind a man who kept

walking away.

No answers followed him

down the gravel drive,

No answers followed him

down the gravel drive,

but many questions had risen.

Behind were a room of scholars

standing among half-packed boxes

amid evening's lengthening shadows.

They had argued about time,

debated about memory,

held stubbornly to the limits of belief.

But none spoke at the moment.

Behind were a room of scholars

standing among half-packed boxes

amid evening's lengthening shadows.

They had argued about time,

debated about memory,

held stubbornly to the limits of belief.

But none spoke at the moment.

Each were silent in their own way.

Contemplative.

Because somewhere -

between a question, and a story -

something had shifted.

between a question, and a story -

something had shifted.

A weight had descended,

and the oldest truth in the room

was not fourteen thousand years old.

was not fourteen thousand years old.

It was the realization

that life was not something

one could possess...

Only something

one could participate in

one could possess...

Only something

one could participate in

as the oldest of processes in the universe.

R.E. Slater

March 5, 2026

@copyright R.E. Slater Publications

all rights reserved

@copyright R.E. Slater Publications

all rights reserved