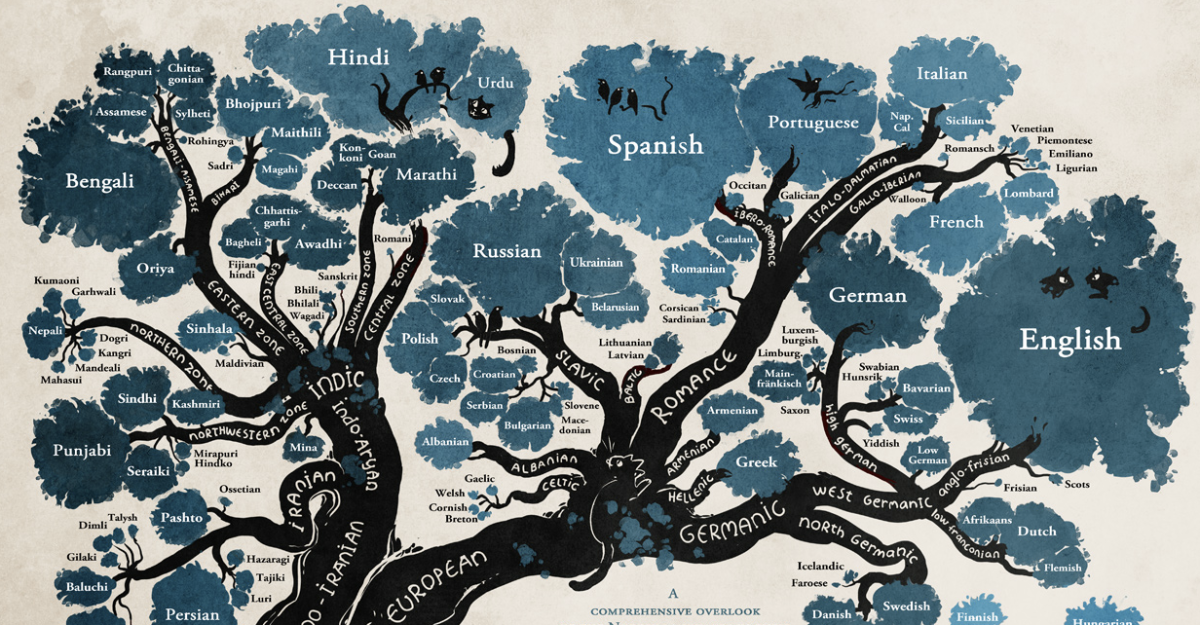

The origin of language:

what’s underneath the tree of languages.

by Thomas Wier

The question of the origin of language is by far the most interesting and probably the most mysterious in linguistic research. The answer to this question is complicated by a number of factors, some of which are obvious and some of which are not. There are many attemts out there chasing the so-called Proto Language, but they all remain a long shot in the dark. The present explanation remains very closely aimed at this question, and provides a very researched-backed account to this interesting issue by stiching together linguistic, biological, and evolutionary facts to fit in the bigger picture of language origin. Before we get to when language evolved, we first need to know what evolved.

THE FOSSIL RECORD

Let’s start with the obvious fact that language leaves no fossil record. Ancient peoples (including other hominids) may have had spoken language, but if a language dies out completely, as theirs certainly have, we have no idea how it functioned and therefore whether it was like modern languages. All we have to go on is physical remains of actual bodies. From the perspective of the fossil record, here is what we know happened:

A. Other hominid species had similar but not identical vocal tracts — e.g. Neanderthals had hyoid bones like we do, though this is only a necessary and not a sufficient factor in human vocalization.

B. Earlier hominid species had brain cases both of increasing size and increasing complexity. Unfortunately, we can derive relatively very little information about how language functioned from this fact alone — almost nothing at all, in fact. It is even disputable that an enlargement in the brain mass and/or development of particular regions of the brain have a direct implication for particular functions of the brain, which in all cases is of course missing.

|

| A Neanderthal hyoid bone (replica) |

WHAT IS LANGUAGE?

Evolution essentially never operates by great leaps but instead usually operates by small changes that accumulate over time. I think this is the key fact that we must consider: how could something as seemingly complex and interconnected as language evolve on its own? I’d argue that’s because most people who’ve made proposals before have not fully articulated what evolved.

I think we can do this by breaking down the human language faculty into its component characteristics. In the 1950s and 60s, Charles Hockett articulated what he called the Design Features of Language, a set of criteria that distinguish different kinds of animal communications systems from each other. This was important because it anchored the study of the origins of human speech firmly in a biological context with which we could compare the properties of human languages with that of other species. These design features relevant for humans included:

- The use of a vocal-auditory tract — humans emit noises from their bodies to communicate, and do not emit chemical trails or flashes of light as other species do.

- Broadcast transmission and directional reception: human speech spreads through the air in all directions, and is received by anyone within the field of broadcast.

- Transitoriness — human speech fades rapidly and can only be received roughly at the time of transmission.

- Interchangeability — a human has the ability to both send and receive the same signal. This is not true of some kinds of insect communication, for example.

- Total feedback — a human has the ability to hear oneself.

- Specialization — human language sounds are specialized for the use of language and do not in general have any other functional use.

- Semanticity — human speech signals can be matched with specific predictable meanings

- Arbitrariness — the relationship between the semantic content of the speech signal and the acoustic form of that signal is essentially arbitrary (onomatopoeia are the exceptions that prove the rule).

- Discreteness — human speech signals can be broken down into discrete units that do not bear any meaning in and of themselves (namely, phonemes).

- Displacement — human speech can be used outside of the contexts for which the signal was originally designed (all kinds of natural language negation might fall under this phenomenon).

- Productivity – language can be used to create new and unique meanings that have never been uttered before.

- Traditional transmission — the actual words of human languages are not innate, but are rather trasmitted from one generation to the next via culture.

- Duality of patterning — meaningless units of sound are combined to create meaningful words.

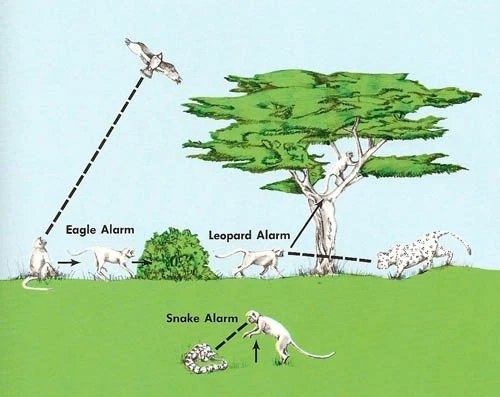

Some of these criterial features of language are related to each other; others are independent. What is important to recognize though is how many of these criteria are found in the communication systems of other plants and animals. For example, the highly complex system of alarm calls used by vervet monkeys to warn the troop of predators involves many of these features, including the vocal-auditory tract, transitoriness, broadcast transmission, semanticity, and even arbitrariness, since a call for an eagle has no particular iconic similarity to an eagle in comparison to that for a leopard (the uniqueness of arbitrariness of human languages has been exaggerated by some).

TIMING

I think Hockett’s list of criterial features gives us a much better starting point than trying to intuit language-y things from the fossil record. More importantly, it allows us to compartmentalize the development of particular aspects of language in particular parts of human evolution, and does not require us to believe all facets of it exploded into being all at once. To get the relative timing of these events though requires us to look at these Hockettian criteria through cladistics, the study of branching relationships in species, languages, etc. In cladistics, the principle of cladistic parsimony suggests that if two organisms Y and Z descend from an ancestor X, and both descendants have the same evolutionary feature, then we must assume that that that feature was also present in their ancestor organism. Using this cladistic principle we can trace the evolution of specific features back quite a long way:

The use of the Vocal-Auditory tract for communication has probably been with us primates for tens of millions of years, since the origin of primates in fact, if not before that. The same goes for the other early features (2)-(5). At least 65 million years ago to this fellow, Notharctus:

Specialization, Semanticity and Arbitrariness are features that are actually found in nonprimate communication systems, such as those found in birds. This means that these features have arisen independently in different genera of animals and so are probably easier to acquire and therefore (?) earlier than other more sophisticated criteria. I will hazard a guess that we had these by the time our line, close to the apes, broke away from Old World Monkeys about 25 million years ago

Where things really get tricky is identifying when the last five criteria arose, those which truly set us apart from other animal communication systems:

Discreteness basically boils down to the ability of the brain to coordinate the vocal tract to articulate segments of sound and consistently treat those segments of sound separately from other possibly similar segments of sound. Human children start learning to aurally distinguish different speech sounds essentially from birth, and begin to control and articulate different aspects of the vocal tract in the first year of life (the babbling stage). Probably the late Australopithecines had similarly extremely rudimentary ability to articulate different kinds of speech sounds consistently on target, as it were, but we can’t know for sure if this is true and when these facts became categorical phonemes in the modern sense (probably the distinction between phones and phonemes is late in the evolution of speech). I will assign this a (somewhat arbitrary) age though of 2-3 million years ago.

Once our ancestors had discreteness, they were primed to evolve Productivity (because they could suddenly create many more words than they could have before) and the Duality of Patterning (since discreteness largely implies that sounds are distinct from meaning). I really don’t know when this might have evolved, but we would want to look for evidence that early hominids’ interactions with their environment are increasingly complex both in the sense of tool use and in the manner in which they process food. Homo erectus arises on the scene roughly 1.8 million years ago (either in east Africa or, less likely, perhaps in what is now the Middle East as evidenced by the finds in Dmanisi Georgia). One of the things we know about H. Erectus is that they had more advanced tool designs than earlier Australopithecines, and they discovered how to manipulate fire and they also learned how to cook food. To my mind, this increasingly sophisticated kind of manipulation of their environment could have necessitated the kind of proto-language that we have been talking about here. I will guesstimate an age based on the earliest evidence of fire being used for cooking, splitting the difference between the oldest suggested ages and the youngest: 900k to 1 million years ago.

The most sophisticated aspects of human language on Hockett’s list are aspects of traditional transmission and displacement, the ability to use language outside of the context for which it was envisioned. These facets of language use would be necessary for the development of idioms and any lexicon larger than a few hundred words. We know that displacement is one of the features that human babies learn somewhat late, around the age 3-4 if I recall correctly, so it must have been very late to evolve. Displacement would also have been necessary to use any form of negation, to talk about is not happening, as well as any form of tense system that distinguishes past, present and future. Combined, these two features would allow something like the kind of discourse possible in the most technologically primitive societies today.. Because we have (very) tentative evidence of art among Neanderthals (though nowhere near as much as from the earliest Homo sapiens) and other evidence that Neanderthals could plan for the future, I will take a shot in the dark and say that something like the earliest form of modern language appeared at roughly the time H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens speciated, around 450-500k years ago.

So, there we have it: evolutionarily modern human language might have arisen about half a million years ago.

I want to stress that much of this timeline is highly speculative. My specialization is linguistics, not human evolution (although I do read quite a bit about human evolution in my spare time). I would like to invite any specialists in human evolution to cross-check their understanding of the fossil evidence with what I have articulated here.

So, did language evolve only once?

If we view language evolution as a complicated multistage process, the question becomes moot, since ‘language’ is not one thing but many. At each stage of human language evolution, some of our ancestors developed a more advanced form of communication, and others did not. Half a million years ago, when there were probably at least four or five different hominid species still extant (H. sapiens, H. neanderthalensis, H. denisova, H. floresiensis, and H. erectus), probably each of these hominids had some form of communication system more advanced than any nonhominid communication system. Where we draw the line between proto-language and full-on language is to a certain extent a matter of degree than a categorial fact.

No comments:

Post a Comment