The Origins of Language

Dr. C. George Boeree

It is an intriguing question, to which we may never have a complete answer: How did we get from animal vocalization (barks, howls, calls...) to human language?

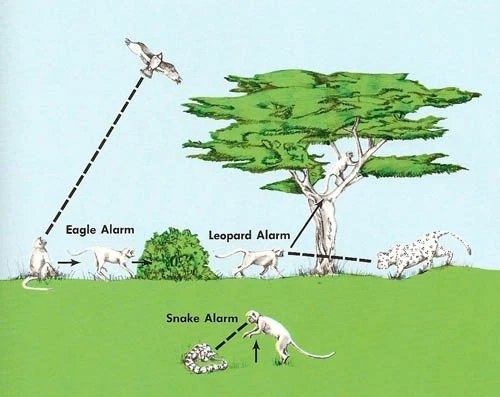

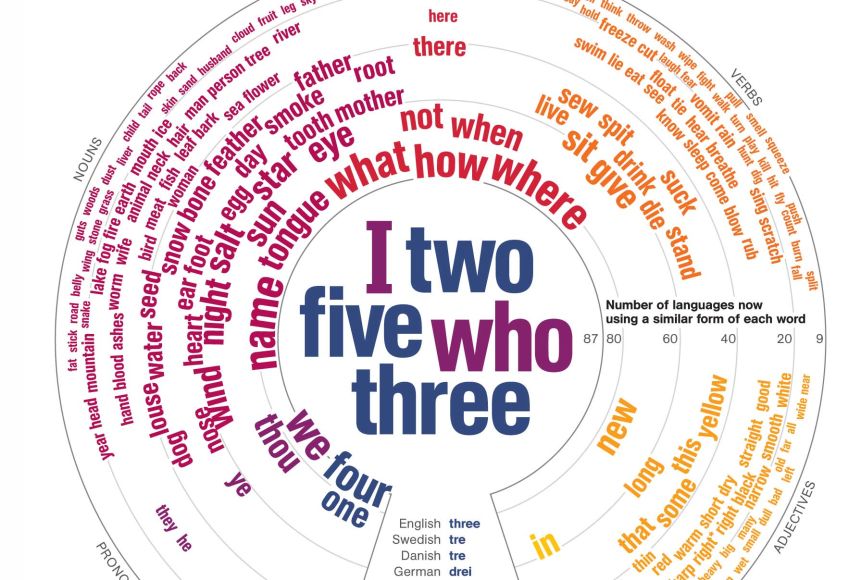

Animals often make use of signs, which point to what they represent, but they don't use symbols, which are arbitrary and conventional. Examples of signs include sniffles as a sign of an on-coming cold, clouds as a sign of rain, or a scent as a sign of territory. Symbols include things like the words we use. Dog, Hund, chien, cane, perro -- these are symbols that refer to the creature so named, yet each one contains nothing in it that in anyway indicates that creature.

In addition, language is a system of symbols, with several levels of organization, at least phonetics (the sounds), syntax (the grammar), and semantics (the meanings).

So when did language begin? At the very beginnings of the genus Homo, perhaps 4 or 5 million years ago? Before that? Or with the advent of modern man, Cro-magnon, some 125,000 years ago? Did the neanderthal speak? We don't know.

There are many theories about the origins of language. Many of these have traditional amusing names (invented by Max Müller and George Romanes a century ago), and I will create a couple more where needed.

1. The mama theory. Language began with the easiest syllables attached to the most significant objects.

2. The ta-ta theory. Sir Richard Paget, influenced by Darwin, believed that body movement preceded language. Language began as an unconscious vocal imitation of these movements -- like the way a child's mouth will move when they use scissors, or my tongue sticks out when I try to play the guitar. This evolved into the popular idea that language may have derived from gestures.

3. The bow-wow theory. Language began as imitations of natural sounds -- moo, choo-choo, crash, clang, buzz, bang, meow... This is more technically refered to as onomatopoeia or echoism.

4. The pooh-pooh theory. Language began with interjections, instinctive emotive cries such as oh! for surprise and ouch! for pain.

5. The ding-dong theory. Some people, including the famous linguist Max Muller, have pointed out that there is a rather mysterious correspondence between sounds and meanings. Small, sharp, high things tend to have words with high front vowels in many languages, while big, round, low things tend to have round back vowels! Compare itsy bitsy teeny weeny with moon, for example. This is often referred to as sound symbolism.

6. The yo-he-ho theory. Language began as rhythmic chants, perhaps ultimately from the grunts of heavy work (heave-ho!). The linguist A. S. Diamond suggests that these were perhaps calls for assistance or cooperation accompanied by appropriate gestures. This may relate yo-he-ho to the ding-dong theory, as in such words as cut, break, crush, strike...

7. The sing-song theory. Danish linguist Jesperson suggested that language comes out of play, laughter, cooing, courtship, emotional mutterings and the like. He even suggests that, contrary to other theories, perhaps some of our first words were actually long and musical, rather than the short grunts many assume we started with.

8. The hey you! theory. A linguist by the name of Revesz suggested that we have always needed interpersonal contact, and that language began as sounds to signal both identity (here I am!) and belonging (I'm with you!). We may also cry out in fear, anger, or hurt (help me!). This is more commonly called the contact theory.

9. The hocus pocus theory. My own contribution to these is the idea that language may have had some roots in a sort of magical or religious aspect of our ancestors' lives. Perhaps we began by calling out to game animals with magical sounds, which became their names.

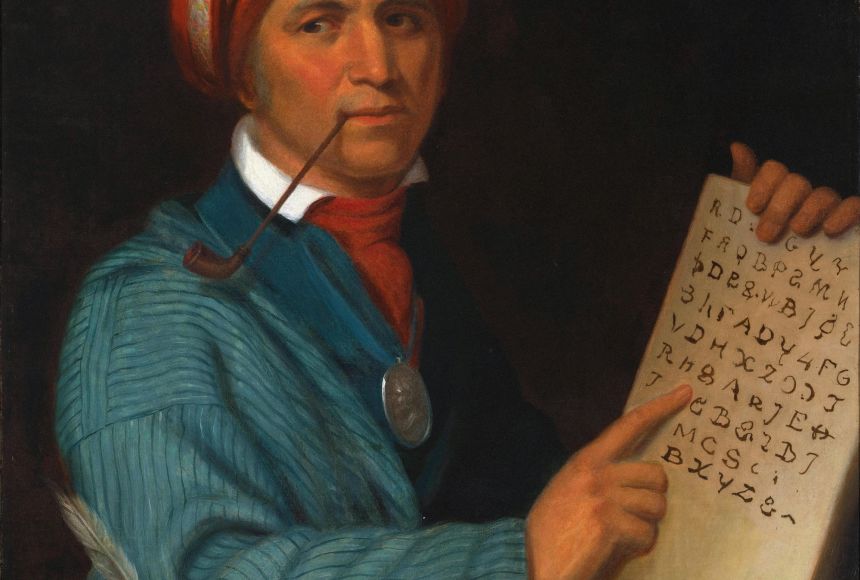

10. The eureka! theory. And finally, perhaps language was consciously invented. Perhaps some ancestor had the idea of assigning arbitrary sounds to mean certain things. Clearly, once the idea was had, it would catch on like wild-fire!

Another issue is how often language came into being (or was invented). Perhaps it was invented once, by our earliest ancestors -- perhaps the first who had whatever genetic and physiological properties needed to make complex sounds and organize them into strings. This is called monogenesis. Or perhaps it was invented many times -- polygenesis -- by many people.

We can try to reconstruct earlier forms of language, but we can only go so far before cycles of change obliterate any possibility of reconstruction. Many say we can only go back perhaps 10,000 years before the trail goes cold. So perhaps we will simply never know.

Water Babies

It may help us understand the origins of languages if we take a look at what is sometimes called the Hardy-Morgan hypothesis, for the orijinator of the hypothesis - Alister Hardy, an English marine biologist, and Elaine Morgan, a Welsh writer and journalist. It is more commonly known as the aquatic ape theory.

Humans have quite a few characteristics we don't share with our primate relatives. We don't have much body hair; we have a layer of fat under our skin; we have a descended larynx; we produce tears; we sweat a lot; we tend to have sex face-to-fact; we can hold our breath quite easily; we are able to swim even before we walk; and most importantly, we walk on our two legs just about all the time.

Hardy, in the 1960s suggested that perhaps (he was cautious, and waited 30 years to tell anyone about his idea) we, or at least our genus, Homo, must have spent some portion of our existence on this planet in the water, wading, swimming, even diving. This may have been why we learned to stand up straight (while wading, supported by water), then evolving the strength and coordination to do so without the support, and only then proceeding into the savannah.

There are other animales that have some of our odd characteristics: sea mammals like whales and dolphins have little hair, hold their breath, and have extra fat under their skin; others, like otters, have a lot of hair, but share the other abilities with us. The only other land animal that shares our lack of hair is the elephant, whose closest relatives include dugongs and manatees. Perhaps elephants, too, spent a portion of their evolution in the water. They do still breath through their trunks when under water. (Gaeth et al 1999)

Perhaps our commonalities with these animals also extend to language.

Musical Babies

Darwin himself once said "Humans don't speak unless they are taught to do so", ie language is learned, and not innate in the way that the famous linguist Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker, the author of "The Language Instinct" say.

Mario Vaneechoutte and his students suggest that language comes from music, with some assitance from gestures and dance. Music is what is innate, not language. Like in many species of birds and mammals, singing (which uptight scientists prefer to call "calls", in order to keep language as our "special ability" distinct) in order to call for help, keep track of each other, and - most especially - in order to attract mates. That use of sound is most definitely something that can evolve, from simple to the complex.

Babies like music. They love listening to their mothers speak to them. The mothers like to use a sort of sing-song speech ("motherese"), which babies like even more. Babies begin to vocalize in very "musical" ways, and often hum or sing in short or long "phrases", with modulations. Babies prefer major rather than minor intervals. And before they even learn individual words, they imitate the "melody of speech" (prosody). Even fetuses can remember sounds in the last trimester.

Because our larynx is lower in the throat, our tongues are free to move around inside the mouth more and our ability to hold our breath means we can control our exhaling and inhaling. We are born ready to make music and so speech. In fact, music and speech use the same areas of the brain, including Broca's area.

In regards to dancing, we see babies moving rhythmically while listening to music and even when not. We see the ease with which they can imitate the movements of others (perhaps by way of the famous "mirror neurons"?). And regarding gestures, maybe you have noticed the connection between movements of the body, especially the hands, and movements of the mouth, especially the tongue. I still stick out my tongue when I try to play guitar, and I have seen children make grinding movements of their mouths when using the old school pencil sharpeners.

A lot of the grammar that seems so essential when we look at written language, in speech is much more obvious: We use pauses, tone changes, melodies, rhythms, eye movements, facial expressions, and gestures that add information to our speech. Perhaps you (like myself) use the pauses we hear or imagine to guide our use of commas and periods. And perhaps you have noticed how much more difficult it is to understand someone when talking on the phone than when you are across the table from them.

In addition to the hypothesis that we were once "aquatic apes", Vaneechoutte adds that we were and still are very much "musical apes".

References

Chomsky. N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton, The Hague.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Concise Editon and Commentary by Carl Zimmer (2007), Plume, Penguin Books.

Gaeth, A.P., Short, R.V., & Renfree, M.B. (1999). The Developing Renal, Reproductive, and Respiratory Systems of the African Elephant Suggest an Aquatic Ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 5555–5558.

Hardy, Alister Clavering (1977). "Was there a Homo aquaticus?". Zenith. 15 (1): 4–6.

Morgan, E. (1997). The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis - The Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution. London, UK: Souvenir Press.

Pinker, S. (1994). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. New York: Morrow.

Vaneechoutte, M., & Skoyles, J.R. (1998). The Memetic Origin of Language: Humans as Musical Primates. J. Memetics, 2. Accessible at: http://users.ugent.be/~mvaneech/ORILA.FIN.html

Vaneechoutte, M. (2014). The Origin of Articulate Language Revisited: The Potential of a Semi-Aquatic Past of Human Ancetors to Explain the Orijin of Human Musicality and Articulate Language. Human Evolution, 29, 1-33.

© Copyright 2003, C. George Boeree