Dr. Darren Sumner is an Affiliate Assistant Professor of Theology at Fuller Theological Seminary where he teaches courses in historical and systematic theology. He lives in the Seattle area with his wife and three children, teaching with Fuller Online and throughout western Washington. He is a member of the Presbyterian Church (USA).

Book 1: The Swiss Reformed Theologian Emil Brunner was one of the key figures in the early 20th century theological movement of Dialectical Theology. In this monograph David Gilland offers an account of Bruner's earlier theology in relation to one of the central themes of the Protestant Reformation: Law and Gospel. He examines Brunner's early relationship with fellow Swiss Reformed theologian, Karl Barth and provides a detailed reading of a variety of Brunner's essays from the early to mid-1920s, centering on Brunner's efforts to use the law-gospel relationship to establish a basis for Christian theology. After analyzing the influence this has on Brunner's theological method, Gilland examines Brunner's earliest text on Christology, The Mediator (1927). In light of the preceding analysis, the fourth chapter provides a careful reading of Brunner's controversial polemic against Karl Barth, Nature and Grace (1934).The monograph concludes with reflections on Brunner's earlier theological work and his turbulent relationship with Karl Barth.

Book 2: This work demonstrates the significance of Karl Barth's Christology by examining it in the context of his orientation toward the classical tradition - an orientation that was both critical and sympathetic. To compare this Christology with the doctrine's history, Sumner suggests first that the Chalcedonian portrait of the incarnation is conceputally vulnerable at a number of points. By recasting the doctrine in actualist terms - the history of Jesus' lived existence as God's fulfillment of His covenant with creatures, rather than a metaphysical uniting of natures - Barth is able to move beyond problems inherent in the tradition. Despite a number of formal and material differences, however, Barth's position coheres with the intent of the ancient councils and ought to be judged as orthodox. Barth's great contribution to Christology is in the unapologetic affirmation of 'the humanity of God'.

Book 3: Divine Freedom and the Doctrine of the Immanent Trinity is widely acclaimed by scholars in the field of Christian systematic theology. Molnar's quest to place the doctrine of the immanent Trinity on the agenda of the Christian doctrine of God has proven to be a signal contribution to the debate in contemporary Christian theology.The material in this second edition has been thoroughly updated: it contains a new preface and a new introduction, as well as a revised bibliography. The book includes a brand new chapter titled 'Divine Freedom Revisited' which addresses those questions that have arisen in connection with Molnar's original presentation of the divine freedom. Molnar re-visits here his discussion of the Logos Asarkos, the theologies of Karl Rahner and Wolfhart Pannenberg. He sheds new light on Rahner's and Torrance's discussions of the Resurrection; and incorporates modern discussions by contemporary theologians to offer new insights into Eberhard Jüngel's thinking.

Book 4: This volume argues that the notion of “affections” discussed by Jonathan Edwards (and Christian theologians before him) means something very different from what contemporary English speakers now call “emotions.” and that Edwards's notions of affections came almost entirely from traditional Christian theology in general and the Reformed tradition in particular.Ryan J. Martin demonstrates that Christian theologians for centuries emphasized affection for God, associated affections with the will, and distinguished affections from passions; generally explaining affections and passions to be inclinations and aversions of the soul. This was Edwards's own view, and he held it throughout his entire ministry. Martin further argues that Edwards's view came not as a result of his reading of John Locke, or the pressures of the Great Awakening (as many Edwardsean scholars argue), but from his own biblical interpretation and theological education. By analysing patristic, medieval and post-medieval thought and the journey of Edwards's psychology, Martin shows how, on their own terms, pre-modern Christians historically defined and described human psychology.

Book 5: David Emerton argues that Dietrich Bonhoeffer's ecclesial thought breaks open a necessary 'third way' in ecclesiological description between the Scylla of 'ethnographic' ecclesiology and the Charybdis of 'dogmatic' ecclesiology. Building on a rigorous and provocative discussion of Bonhoeffer's thought, Emerton establishes a programmatic theological grammar for any speech about the church.Emerton argues that Bonhoeffer understands the church as a pneumatological and eschatological community in space and time, and that his understanding is built on eschatological and pneumatological foundations. These foundations, in turn, give rise to a unique methodological approach to ecclesiological description – an approach that enables Bonhoeffer to proffer a genuinely theological account of the church in which both divine and human agency are held together through an account of God the Holy Spirit. Emerton proposes that this approach is the perfect remedy for an endemic problem in contemporary accounts of the church: that of attending either to the human empirical church-community ethnographically or to the life of God dogmatically; and to each, problematically, at the expense of the other. This book will act as a clarion call towards genuinely theological ecclesiological speech which is allied to real ecclesial action.

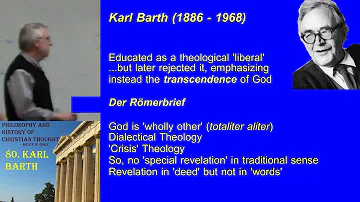

Theology of Karl Barth

Multimedia

- The Theology of Karl Barth (YouTube)

The triune God

"The doctrine of the Trinity is what basically distinguishes the Christian doctrine of God as Christian, and therefore what already distinguishes the Christian concept of revelation as Christian, in contrast to all other possible doctrines of God or concepts of revelation." ^[1]^

"It can fairly be said that the chief ecumenical enterprise of current theology is rediscovery and development of the doctrine of the Trinity. It can also fairly be said that Barth initiated the enterprise" ^[2]^ Robert Jenson's quote must be seen in the context of Friedrich Schleiermacher, who placed the Trinity at the end of his systematic work, The Christian Faith (1821, rev. 1830). Barth purposefully placed the Trinity at the beginning of his Church Dogmatics, signifying its importance and centrality to the exposition and proclamation of theology. Since Barth, Protestant theologians have found a renewed interest in the Trinity, and contemporary theology has seen it return to the forefront of dogmatics and theological method.

Threefold Word of God

Barth held to what is known as the threefold Word of God. In other words, preaching (or proclamation), scripture, and revelation are considered to be three different, yet unified forms of the Word of God. Barth's analogy was the Trinity (see CD I/1, 121). Futhermore,

There is no distinction of degree or value between these three forms. For to the extent that proclamation really rests on recollection of the revelation attested in the Bible and is thus obedient repitition of the biblical witness, it is no less the Word of God than the Bible. And to the extent that the Bible really attests revelation it is no less the Word of God than revelation itself. As the Bible and proclamation become God's Word in virtue of the actuality of revelation, they are God's Word: the one Word of God within which there can be neither a more nor a less. Nor should we ever try to understand the three forms of God's Word in isolation. The first, revelation, is the form that underlies the other two (CD I/1, 120-121). Bruce McCormack notes that what Barth is after is a "unity-in-differentiation." ^[3]^ Each form is distinct from one another (as the persons of the Trinity are), yet are unified with each other (cf. CD I/2, 463).

Preaching

"Real proclamation, then, means the Word of God preached and the Word of God preached means... man's talk about God on the basis of God's own direction, which fundamentally transcends all human causation, which cannot, then, be put on a human basis, but which simply takes place, and has to be acknowledged, as a fact" (CD I/1, 90). Barth's point is that preaching may become the Word of God not because of something we do, but according to God's direction. Thus, God's Word is free and not something controlled or possessed by the church.

Scripture

Revelation

Election

One of the most influential and controversial features of Barth's Church Dogmatics was his doctrine of election (see CD II/2). One thread of the Reformed tradition, following the interpretation of its most influential thinker, John Calvin, argued for the so-called double predestination: God chose some humans for salvation through Christ and others for damnation. These groups were sometimes called the "elect" and "reprobate." This choice (or election) was made by God and was the result of His "absolute decree," a mysterious and fundamentally inscrutable decision which, though it was a decision of ultimate consequence for the individual human, was fundamentally inaccessible and unknowable to him or her. God chose each person to be saved or damned based on the divine will, and it was impossible to know why God chose some and not others or whether God had elected or rejected oneself.

Barth's doctrine of election involves a firm rejection of the notion of an absolute decree. In keeping with his Christo-centric methodology, Barth argues that to ascribe the salvation or damnation of humanity to an abstract and absolute decree is to make some part of God more final and definitive than God's saving act in Jesus Christ. God's absolute decree, if one may speak of such a thing, is God's gracious decision to be "for" humanity in the person of Jesus Christ (Barth calls this God's "Yes"). With the earlier Reformed tradition, Barth retains the notion of double predestination, but he makes Jesus simultaneously the object and subject of both divine election and reprobation: Jesus embodies God's election of humanity and God's rejection of human sin. He is the electing God and the elect man. As the electing God, Jesus elects all of humanity in himself. And thus, as the elected man, all who are "in Christ" are elect in him. Non-believers, it is said, have simply not realized or recognized their election in Christ.

While some regard this revision of the doctrine of election as an improvement on the Calvinist doctrine of double predestination,^[[citation\ needed](Theopedia:Writing_guide#Reference_your_work)]^ critics have charged that Barth's view amounts to an implicit universalism.^[[citation\ needed](Theopedia:Writing_guide#Reference_your_work)]^

Universalism?

Barth has also been criticized for his alleged belief in universalism, however, Barth himself noted that insistence on necessary universal salvation impinged on God's freedom and suggested it was beyond the church's duty to speculate on the subject (Church Dogmatics 2.2, 417). "For Barth, the grace of God is characterised by freedom. On the one hand, this means that we can never impose limits on the scope of grace; and on the other hand, it means that we can never impose a universalist 'system' on grace. In either case, we would be compromising the freedom of grace - we would be presuming that we can define the exact scope of God's liberality. So Barth's theology of grace includes a dialectical protest: Barth protests both against a system of universalism and against a denial of universalism! The crucial point is that God's grace is free grace: it is nothing other than God himself acting in freedom. And if God acts in freedom, then we can neither deny nor affirm the possibility of universal salvation." ^[4]^

Barth says that,

"The proclamation of the Church must make allowance for this freedom of grace. Apokatastasis Panton? No, for a grace which automatically would ultimately have to embrace each and every one would certainly not be free grace. It surely would not be God's grace. But would it be God's free grace if we could absolutely deny that it could do that? Has Christ been sacrificed only for our sins? Has he not ... been sacrificed for the whole world? ... [Thus] the freedom of grace is preserved on both these sides." ^[5]^ For Barth, then, we can neither affirm nor deny the possibility that all will be saved. So what can we do? Barth's answer is clear: we can hope (see CD IV/3, pp. 477-78). ^ [6]^

Apologetics

Barth's theology denies the necessity of apologetics. He states in The Epistle to the Romans:

The Gospel is not a truth among other truths. Rather, it sets a question-mark against all truths. The Gospel is not the door but the hinge. The man who apprehends its meaning is removed from all strife, because he is engaged in a strife with the whole, even with existence itself. Anxiety concerning the victory of the Gospel--that is, Christian Apologetics--is meaningless, because the Gospel is the victory by which the world is overcome. ... It [the Gospel] does not require representatives with a sense of responsibility, for it is as responsible for those who proclaim it as it is for those to whom it is proclaimed. It is the advocate of both. ... God does not need us. Indeed, if He were not God, He would be ashamed of us. We, at any rate, cannot be ashamed of Him. ^[7]^

Abbreviations

- CD - Church Dogmatics

- GD - Gottingen Dogmatics

Notes

- ↑ Church Dogmatics I/1, p. 301.

- ↑ Robert Jenson, "Karl Barth" in The Modern Theologians 2nd ed., p. 47.

- ↑ Bruce McCormack, "The Being of Scripture is in Becoming", in Evangelicals & Scripture: Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics, eds. Vincent Bacote, Laura C. Miguelez, and Dennis L. Okholm (InterVarsity Press, 2004), p. 59.

- ↑ Why I am not a Universalist, by Ben Meyers

- ↑ Barth, God Here and Now, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Why I am not a Universalist, by Ben Meyers

- ↑ p. 35

Suggested reading

For primary resources, see the main page Karl Barth and the Barth bibliography.

Introductions

- John Webster, Barth, 2nd edition. Continuum, 2004.

- Paul T. Nimmo, Karl Barth: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark, 2013.

- Colin Gunton, The Barth Lectures. T&T Clark, 2007.

- Eberhard Busch, Barth. Abingdon Pillars of Theology. Abingdon, 2008.

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley, An Introduction to the Theology of Karl Barth. Eerdmans, 1979; T&T Clark, 1991.

- Eberhard Busch, The Great Passion: An Introduction to Karl Barth's Theology. Eerdmans, 2004.

- George Hunsinger, How to Read Karl Barth: The Shape of His Theology. Oxford UP, 1993.

- John Franke, Barth for Armchair Theologians. WJK, 2006.

Other studies

- Bruce McCormack, Orthodox and Modern: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth. Baker Academic, 2008.

- George Hunsinger, Disruptive Grace: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth. Eerdmans, 2000.

- Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Theology of Karl Barth: Exposition and Interpretation. Ignatius, 1992.

- John Webster, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Karl Barth. Cambridge UP, 2000.

- G.C. Berkouwer, The Triumph of Grace in the Theology of Karl Barth. Eerdmans, 1956.

Development of thought

- Karl Barth, How I Changed My Mind. John Knox Press, 1966.

- Bruce McCormack, Karl Barth's Critically Realistic Dialectical Theology: Its Genesis and Development 1909-1936. Oxford UP, 1997.

- Bernd Jaspert, ed. Karl Barth ~ Rudolf Bultmann, Letters 1922-1966. Eerdmans, 1981.

- Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts. Fortress/SCM, 1976; Eerdmans, 1994; reprint Wipf & Stock, 2005.

- John Webster, Barth's Earlier Theology: Four Studies. T&T Clark, 2006.

- T.F. Torrance, Karl Barth: An Introduction to His Early Theology 1910-1931. T&T Clark, 2001.

Barth and Evangelicalism

- David Gibson & Daniel Strange, eds. Engaging with Barth. Apollos, 2008; T&T Clark, 2009.

- Sung Wook Chung, ed. Karl Barth and Evangelical Theology: Convergences and Divergences. Baker Academic, 2007.

- Bernard Ramm, After Fundamentalism: The Future of Evangelical Theology. Harper & Row, 1983.

- Philip R. Thorne, Evangelicalism and Karl Barth: his reception and influence in North American Evangelical theology. Pickwick, 1995.

- Donald Bloesch Jesus Is Victor!: Karl Barth's Doctrine of Salvation. Abingdon, 1976.

- Kurt Anders Richardson, Reading Karl Barth: New Directions for North American Theology. Baker Academic, 2004.

- Gregory G. Bolich, Karl Barth & Evangelicalism. IVP, 1979.

Scripture

- Kevin Vanhoozer, "A Person of the Book? Barth on Biblical Authority and Interpretation." In Karl Barth and Evangelical Theology: Convergences and Divergences, ed. Sung Wook Chung, pp. 26-59. Baker Academic, 2006.

- Mark D. Thompson, "Witness to the Word: On Barth's Doctrine of Scripture." In Engaging with Barth: Contemporary Evangelical Critiques, edited by David Gibson and Daniel Strange, pp. 168-197. T&T Clark, 2008.

- Bruce McCormack, "The Being of Holy Scripture is in Becoming: Karl Barth in Conversation With American Evangelical Criticism." In Evangelicals & Scripture: Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics, ed. Vincent Bacote, et al., pp. 55-75. IVP, 2004.

- Francis Watson, "The Bible." In The Cambridge Companion to Karl Barth, ed. John Webster, pp. 57-71. Cambridge UP, 2000.

- Klaas Runia, Karl Barth's Doctrine of Holy Scripture. Eerdmans, 1962.

- Mary Kathleen Cunningham, "Karl Barth." In Christian Theologies of Scripture: A Comparative Introduction, ed. Justin Holcomb, pp. 183-201. NYU Press, 2006.

- Geoffrey Bromiley, "Karl Barth's Doctrine of Inspiration", Journal of the Transactions of the Victoria Institute 87 (1955): 66-80.

Exegesis

- Donald Wood, Barth's Theology of Interpretation. Barth Studies Series. Ashgate, 2007.

- Richard Burnett, Karl Barth's Theological Exegesis: The Hermeneutical Principles of the Romerbrief Period. Eerdmans, 2004.

- John Webster, "Barth, Karl." In Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible, ed. Kevin Vanhoozer, pp. 82-84. Baker Academic, 2005.

- Bruce McCormack, "The Significance of Karl Barth's Theological Exegesis of Philippians." In Epistle to the Philippians, 40th Anniversary Edition, by Karl Barth, pp. v-xxv. WJK, 2002.

- Francis Watson, "Barth's Philippians as Exegesis." In Epistle to the Philippians, 40th Anniversary Edition, by Karl Barth, pp. xxvi-li. WJK, 2002

- Paul McGlasson, Jesus and Judas: Biblical Exegesis in Barth. Scholars Press, 1991.

- Mary Kathleen Cunningham, What is Theological Exegesis? Interpretation and Use of Scripture in Barth's Doctrine of Election. Trinity Press Intl., 1995.

Trinity

- Eberhard Jüngel, God's Being is in Becoming: The Trinitarian Being of God in the Theology of Karl Barth, trans. by John Webster. Eerdmans, 2001; T&T Clark, 2004.

- Paul Molnar, Divine Freedom And the Doctrine of the Immanent Trinity: In Dialogue With Karl Barth And Contemporary Theology. T&T Clark, 2005.

- Peter S. Oh, Karl Barth's Trinitarian Theology: A Study in Karl Barth's Analogical Use of the Trinitarian Relation. T&T Clark, 2007.

- Alan J. Torrance, Persons in Communion: An Essay on Trinitarian Description and Human Participation with special reference to Volume One of Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics. T&T Clark, 1996.

See also

- Karl Barth (main article)

- Neo-Orthodoxy

- Emil Brunner

External links

- The Barth Renaissance in America: An Opinion, by Bruce McCormack

- Karl Barth (Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Modern Western Theology)

- The Doctrine of Sanctification in the Theology of Karl Barth (PDF), by Daniel B. Spross

- Analogy and the Spirit in the Theology of Karl Barth (PDF), by Hans Frei

- Barth, The Trinity, and Human Freedom, by Colin Gunton

- Karl Barth the Preacher (PDF), by Charles M. Cameron. The Evangelical Quarterly 66:2 (1994): 99-106.

- The Covenant of Grace Fulfilled in Christ as the Foundation of the Indissoluble Solidarity of the Church with Israel: Barth´s Position on the Jews During the Hitler Era (PDF), by Eberhard Busch

Scripture

- Karl Barth's Doctrine of Inspiration (PDF), by G.W. Bromiley

- The God of Promise: Christian Scripture as Covenantal Revelation, by David Gibson (discusses Barth's view of Scripture)

Bibliographies

- kbarth.org comprehensive bibliography

- Karl Barth at TheologicalStudies.org.uk

Karl Barth

Karl Barth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 May 1886 |

| Died | 10 December 1968 (aged 82) Basel, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation | Theologian, Professor |

Notable work | The Epistle to the Romans Barmen Declaration Church Dogmatics |

| Spouse(s) | Nelly Hoffmann (m. 1913) |

| Children | Franziska, Markus, Christoph, Matthias and Hans Jakob |

| Theological work | |

| Tradition or movement | Swiss Reformed |

| Part of a series on |

| Calvinism |

|---|

|

Karl Barth (/bɑːrt, bɑːrθ/;[1] German: [baɐ̯t]; 10 May 1886 – 10 December 1968) was a Swiss Reformed theologian who is most well known for his landmark commentary The Epistle to the Romans (1921) (a.k.a. Romans II), his involvement in the Confessing Church, and authorship of the Barmen Declaration,[2][3] and especially his unfinished five volume theological summa the Church Dogmatics[4] (published in twelve part-volumes between 1932–1967).[5][6] Barth's influence expanded well beyond the academic realm to mainstream culture, leading him to be featured on the cover of Time on 20 April 1962.[7]

Barth's theological career began while he was known as the "Red Pastor from Safenwil"[8] when he wrote his first edition of his The Epistle to the Romans (1919) (a.k.a. Romans I). Beginning with his second edition of The Epistle to the Romans (1921), Barth began to depart from his former training – and began to garner substantial worldwide acclaim – with a liberal theology he inherited from Adolf von Harnack, Friedrich Schleiermacher and others.[9] Barth influenced many significant theologians such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer who supported the Confessing Church, and Jürgen Moltmann, Helmut Gollwitzer, James H. Cone, Wolfhart Pannenberg, Rudolf Bultmann, Thomas F. Torrance, Hans Küng, and also Reinhold Niebuhr, Jacques Ellul, and novelists such as Flannery O'Connor, John Updike, and Miklós Szentkuthy. Among many other areas, Barth has also had a profound influence on modern Christian ethics.[10][11][12][13] He has influenced the work of ethicists such as Stanley Hauerwas, John Howard Yoder, Jacques Ellul and Oliver O'Donovan.[10][14][15]

Early life and education

Karl Barth was born on 10 May 1886, in Basel, Switzerland, to Johann Friedrich "Fritz" Barth (1852–1912) and Anna Katharina (Sartorius) Barth (1863–1938).[16] Karl had two younger brothers, Peter Barth (1888–1940) and Heinrich Barth (1890–1965), and two sisters, Katharina and Gertrude. Fritz Barth was a theology professor and pastor and desired for Karl to follow his positive line of Christianity, which clashed with Karl's desire to receive a liberal Protestant education. Karl began his student career at the University of Bern, and then transferred to the University of Berlin to study under Adolf von Harnack, and then transferred briefly to the University of Tübingen before finally in Marburg to study under Wilhelm Herrmann (1846–1922).[17] From 1911 to 1921 he served as a Reformed pastor in the village of Safenwil in the canton of Aargau. In 1913 he married Nelly Hoffmann, a talented violinist. They had a daughter and four sons, one of whom was the New Testament scholar Markus Barth (6 October 1915 – 1 July 1994). Later he was professor of theology in Göttingen (1921–1925), Münster (1925–1930) and Bonn (1930–1935), in Germany. While serving at Göttingen he met Charlotte von Kirschbaum, who became his long-time secretary and assistant; she played a large role in the writing of his epic, the Church Dogmatics.[18] He was deported from Germany in 1935 after he refused to sign (without modification) the Oath of Loyalty to Adolf Hitler and went back to Switzerland and became a professor in Basel (1935–1962).

Break from liberalism

In August 1914, Karl Barth was dismayed to learn that his venerated teachers including Adolf von Harnack had signed the "Manifesto of the Ninety-Three German Intellectuals to the Civilized World";[19] as a result, Barth concluded he could not follow their understanding of the Bible and history any longer.[20]

The Epistle to the Romans

Barth first began his commentary The Epistle to the Romans (Ger. Der Römerbrief) in the summer of 1916 while he was still a pastor in Safenwil, with the first edition appearing in December 1918 (but with a publication date of 1919).[8] On the strength of the first edition of the commentary, Barth was invited to teach at the University of Göttingen. Barth decided around October 1920 that he was dissatisfied with the first edition and heavily revised it the following eleven months, finishing the second edition around September 1921.[8][21] Particularly in the thoroughly re-written second edition of 1922, Barth argued that the God who is revealed in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus challenges and overthrows any attempt to ally God with human cultures, achievements, or possessions. The book's popularity led to its republication and reprinting in several languages.

Barmen Declaration

In 1934, as the Protestant Church attempted to come to terms with the Third Reich, Barth was largely responsible for the writing of the Barmen Declaration (Ger. Barmer Erklärung).[22] This declaration rejected the influence of Nazism on German Christianity by arguing that the Church's allegiance to the God of Jesus Christ should give it the impetus and resources to resist the influence of other lords, such as the German Führer, Adolf Hitler.[23] Barth mailed this declaration to Hitler personally. This was one of the founding documents of the Confessing Church and Barth was elected a member of its leadership council, the Bruderrat.

He was forced to resign from his professorship at the University of Bonn in 1935 for refusing to swear an oath to Hitler. Barth then returned to his native Switzerland, where he assumed a chair in systematic theology at the University of Basel. In the course of his appointment, he was required to answer a routine question asked of all Swiss civil servants: whether he supported the national defense. His answer was, "Yes, especially on the northern border!"[citation needed] The newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung carried his 1936 criticism of the philosopher Martin Heidegger for his support of the Nazis.[24] In 1938 he wrote a letter to a Czech colleague Josef Hromádka in which he declared that soldiers who fought against the Third Reich were serving a Christian cause.

Church Dogmatics

Barth's theology found its most sustained and compelling expression in his five-volume magnum opus, the Church Dogmatics (Ger. "Kirchliche Dogmatik"). Widely regarded as an important theological work, the Church Dogmatics represents the pinnacle of Barth's achievement as a theologian. Church Dogmatics runs to over six million words and 9,000 pages – one of the longest works of systematic theology ever written.[26][27][28] The Church Dogmatics is in five volumes: the Doctrine of the Word of God, the Doctrine of God, the Doctrine of Creation, the Doctrine of Reconciliation and the Doctrine of Redemption. Barth's planned fifth volume was never written and the fourth volume's final part-volume was unfinished.[29][30][31]

Examples of Karl Barth's contributions to theology

Some theologians have suggested that Karl Barth's greatest contributions to theology may be summarized on one sheet of paper, but others have argued that is impossible to reduce his published works in such a way. Some of Karl Barth's best ideas include the following loci:[32]

- Threefold Word of God (cf. CD I/1, CD I/2 19–21)

- Doctrine of Election: The Electing and Elected Jesus Christ (c.f CD II/2, 33)

- No to Natural Revelation (cf. Doctrine of God, CD II/1, CD IV/3.1, and the Barmen Declaration).

- Creation as the exterior basis of the covenant and Covenant as the interior basis of creation (cf. CD III/1)

- Christian Anthropology: Soul of my Body (cf. CD III/2)

- The Judge Judged in our Place. (cf. CD IV/1)

Later life and death

After the end of the Second World War, Barth became an important voice in support both of German penitence and of reconciliation with churches abroad. Together with Hans Iwand, he authored the Darmstadt Statement in 1947 – a more concrete statement of German guilt and responsibility for the Third Reich and Second World War than the 1945 Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt. In it, he made the point that the Church's willingness to side with anti-socialist and conservative forces had led to its susceptibility for National Socialist ideology. In the context of the developing Cold War, that controversial statement was rejected by anti-Communists in the West who supported the CDU course of re-militarization, as well as by East German dissidents who believed that it did not sufficiently depict the dangers of Communism. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950.[33] In the 1950s, Barth sympathized with the peace movement and opposed German rearmament.

Barth wrote a 1960 article for The Christian Century regarding the "East–West question" in which he denied any inclination toward Eastern communism and stated he did not wish to live under Communism or wish anyone to be forced to do so; he acknowledged a fundamental disagreement with most of those around him, writing: "I do not comprehend how either politics or Christianity require [sic] or even permit such a disinclination to lead to the conclusions which the West has drawn with increasing sharpness in the past 15 years. I regard anticommunism as a matter of principle an evil even greater than communism itself."[34]

In 1962, Barth visited the United States and lectured at Princeton Theological Seminary, the University of Chicago, the Union Theological Seminary and the San Francisco Theological Seminary. He was invited to be a guest at the Second Vatican Council. At the time Barth's health did not permit him to attend. However, he was able to visit the Vatican and be a guest of the pope in 1967, after which he wrote the small volume Ad Limina Apostolorum [At the Threshold of the Apostles].[35]

Barth was featured on the cover of the 20 April 1962 issue of Time magazine, an indication that his influence had reached out of academic and ecclesiastical circles and into mainstream American religious culture.[36] Pope Pius XII is often claimed to have said Barth was "the greatest theologian since Thomas Aquinas,"[disputed ][37][38][39][40] though Fergus Kerr observes that "there is never chapter and verse for the quotation" and it is sometimes attributed to Pope Paul VI instead.[41]

Barth died on 10 December 1968, at his home in Basel, Switzerland. The evening before his death, he had encouraged his lifelong friend Eduard Thurneysen that he should not be downhearted, "For things are ruled, not just in Moscow or in Washington or in Peking, but things are ruled – even here on earth—entirely from above, from heaven above.”[42]

Theology

Karl Barth's most significant theological work is his summa theology titled the Church Dogmatics, which contains Barth's doctrine of the word of God, doctrine of God, doctrine of reconciliation and doctrine of redemption. Barth is most well known for reorienting all theological discussion around Jesus.

Trinitarian focus[edit]

One major objective of Barth is to recover the doctrine of the Trinity in theology from its putative loss in liberalism.[43] His argument follows from the idea that God is the object of God's own self-knowledge, and revelation in the Bible means the self-unveiling to humanity of the God who cannot be discovered by humanity simply through its own intuition.[44] God's revelation comes to man 'vertically from above' (Senkrecht von Oben).

Election

One of the most influential and controversial features of Barth's Dogmatics was his doctrine of election (Church Dogmatics II/2). Barth's theology entails a rejection of the idea that God chose each person to either be saved or damned based on purposes of the Divine will, and it was impossible to know why God chose some and not others.[45]

Barth's doctrine of election involves a firm rejection of the notion of an eternal, hidden decree.[46] In keeping with his Christo-centric methodology, Barth argues that to ascribe the salvation or damnation of humanity to an abstract absolute decree is to make some part of God more final and definitive than God's saving act in Jesus Christ. God's absolute decree, if one may speak of such a thing, is God's gracious decision to be for humanity in the person of Jesus Christ. Drawing from the earlier Reformed tradition, Barth retains the notion of double predestination but makes Jesus himself the object of both divine election and reprobation simultaneously; Jesus embodies both God's election of humanity and God's rejection of human sin.[47] While some regard this revision of the doctrine of election as an improvement[48] on the Augustinian-Calvinist doctrine of the predestination of individuals, critics, namely Brunner,[49] have charged that Barth's view amounts to a soft universalism, thereby departing from Augustinian-Calvinism.

Barth's doctrine of objective atonement develops as he distances himself from Anselm of Canterbury's doctrine of the atonement.[50] In The Epistle to the Romans, Barth endorses Anselm's idea that God who is robbed of his honor must punish those who robbed him. In Church Dogmatics I/2, Barth advocates divine freedom in the incarnation with the support of Anselm's Cur Deus Homo. Barth holds that Anselm's doctrine of the atonement preserves both God's freedom and the necessity of Christ's incarnation. The positive endorsement of Anselmian motives in Cur Deus Homo continues in Church Dogmatics II/1. Barth maintains with Anselm that the sin of humanity cannot be removed by the merciful act of divine forgiveness alone. In Church Dogmatics IV/1, however, Barth's doctrine of the atonement diverges from that of Anselm.[51] By over-christologizing the doctrine, Barth completes his formulation of objective atonement. He finalizes the necessity of God's mercy at the place where Anselm firmly establishes the dignity and freedom of the will of God.[52] In Barth's view, God's mercy is identified with God's righteousness in a distinctive way where God's mercy always takes the initiative. The change in Barth's reception of Anselm's doctrine of the atonement is, therefore, alleged to show that Barth's doctrine entails support for universalism.[49][53]

Salvation

Barth argued that previous perspectives on sin and salvation, influenced by strict Calvinist thinking, sometimes misled Christians into thinking that predestination set up humanity such that the vast majority of human beings were foreseen to disobey and reject God, with damnation coming to them as a matter of fate.

Barth's view of salvation is centrally Christological, with his writings stating that in Jesus Christ the reconciliation of all of mankind to God has essentially already taken place and that through Christ man is already elect and justified.

Karl Barth denied that he was a Universalist.[54] However, Barth asserted that eternal salvation for everyone, even those that reject God, is a possibility that is not just an open question but should be hoped for by Christians as a matter of grace; specifically, he wrote, "Even though theological consistency might seem to lead our thoughts and utterances most clearly in this direction, we must not arrogate to ourselves that which can be given and received only as a free gift", just hoping for total reconciliation.[55]

Barth, in the words of a later scholar, went a "significant step beyond traditional theology" in that he argued against more conservative strains of Protestant Christianity in which damnation is seen as an absolute certainty for many or most people. To Barth, Christ's grace is central.[55]

Understanding of Mary

Unlike many Protestant theologians, Barth wrote on the topic of Mariology (the theological study of Mary). Barth's views on the subject agreed with much Roman Catholic dogma but he disagreed with the Catholic veneration of Mary. Aware of the common dogmatic tradition of the early Church, Barth fully accepted the dogma of Mary as the Mother of God, seeing a rejection of that title equivalent to rejecting the doctrine that Christ's human and divine natures are inseparable (contra the Nestorian heresy). Through Mary, Jesus belongs to the human race. Through Jesus, Mary is Mother of God.[56]

Charlotte von Kirschbaum

Charlotte von Kirschbaum was Barth's theological academic colleague for more than three decades.[57] George Hunsinger summarizes the influence of von Kirschbaum on Barth's work: "As his unique student, critic, researcher, adviser, collaborator, companion, assistant, spokesperson, and confidante, Charlotte von Kirschbaum was indispensable to him. He could not have been what he was, or have done what he did, without her."[58]

An article written in 2017 by Christiane Tietz (originally a paper she delivered at the 2016 American Academy of Religion in San Antonio, Texas) for the academic journal Theology Today engages letters released in both 2000 and 2008 written by Barth, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and Nelly Barth, which discuss the complicated relationship between all three individuals that occurred over the span of 40 years.[59] The letters published in 2008 between von Kirschbaum and Barth from 1925 to 1935[60] made public "the deep, intense, and overwhelming love between these two human beings." [61]

In literature

In John Updike's Roger's Version, Roger Lambert is a professor of religion. Lambert is influenced by the works of Karl Barth. That is the primary reason that he rejects his student's attempt to use computational methods to understand God.

Harry Mulisch's The Discovery of Heaven makes mentions of Barth's Church Dogmatics, as does David Markson's The Last Novel. In the case of Mulisch and Markson, it is the ambitious nature of the Church Dogmatics that seems to be of significance. In the case of Updike, it is the emphasis on the idea of God as "Wholly Other" that is emphasized.

In Marilynne Robinson's Gilead, the preacher John Ames reveres Barth's "Epistle to the Romans" and refers to it as his favorite book other than the Bible.

Whittaker Chambers cites Barth in nearly all his books: Witness (p. 507), Cold Friday (p. 194), and Odyssey of a Friend (pp. 201, 231).

In Flannery O'Connor's letter to Brainard Cheney, she said "I distrust folks who have ugly things to say about Karl Barth. I like old Barth. He throws the furniture around."

Center for Barth Studies

Princeton Theological Seminary, where Barth lectured in 1962, houses the Center for Barth Studies, which is dedicated to supporting scholarship related to the life and theology of Karl Barth. The Barth Center was established in 1997 and sponsors seminars, conferences, and other events. It also holds the Karl Barth Research Collection, the largest in the world, which contains nearly all of Barth's works in English and German, several first editions of his works, and an original handwritten manuscript by Barth.[62][63]

Writings

- The Epistle to the Romans (Ger. Der Römerbrief I, 1st ed., 1919)

- The Epistle to the Romans (Ger. Der Römerbrief. Zweite Fassung, 1922). E. C. Hoskyns, trans. London: Oxford University Press, 1933, 1968 ISBN 0-19-500294-6

- The Word of God and The Word of Man (Ger. Das Wort Gottes und die Theologie, 1928). New York: Harper & Bros, 1957. ISBN 978-0-8446-1599-8; The Word of God and Theology. Amy Marga, trans. New York: T & T Clark, 2011.

- Preaching Through the Christian Year. H. Wells and J. McTavish, eds. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1978. ISBN 0-8028-1725-4

- God Here and Now. London: Routledge, 1964.

- Fides Quaerens Intellectum: Anselm's Proof of the Existence of God in the Context of His Theological Scheme (written in 1931). I. W. Robertson, trans. London: SCM, 1960; reprinted by Pickwick Publications (1985) ISBN 0-915138-75-1

- Church and State. G.R. Howe, trans. London: SCM, 1939.

- The Church and the War. A. H. Froendt, trans. New York: Macmillan, 1944.

- Prayer according to the Catechisms of the Reformation. S.F. Terrien, trans. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1952 (Also published as: Prayer and Preaching. London: SCM, 1964).

- The Humanity of God, J.N. Thomas and T. Wieser, trans. Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1960. ISBN 0-8042-0612-0

- Evangelical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1963.

- The Christian Life. Church Dogmatics IV/4: Lecture Fragments. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981. ISBN 0-567-09320-4, ISBN 0-8028-3523-6

- The Word in this World: Two Sermons by Karl Barth. Edited by Kurt I. Johanson. Regent Publishing (Vancouver, BC, Canada): 2007

- "No Angels of Darkness and Light," The Christian Century, January 20, 1960, p. 72 (reprinted in Contemporary Moral Issues. H. K. Girvetz, ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1963. pp. 6–8).

- The Göttingen Dogmatics: Instruction in the Christian Religion, vol. 1. G.W. Bromiley, trans. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991. ISBN 0-8028-2421-8

- Dogmatics in Outline (1947 lectures), Harper Perennial, 1959, ISBN 0-06-130056-X

- A Unique Time of God: Karl Barth's WWI Sermons, William Klempa, editor. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

- On Religion. Edited and translated by Garrett Green. London: T & T Clark, 2006.

The Church Dogmatics in English translation

- Volume I Part 1: Doctrine of the Word of God: Prolegomena to Church Dogmatics, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09013-2, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05059-9 (German: 1932)

- Volume I Part 2: Doctrine of the Word of God, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09012-4, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05069-6 (German: 1938)

- Volume II Part 1: The Doctrine of God: The Knowledge of God; The Reality of God, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09021-3, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05169-2 (German: 1940)

- Volume II Part 2: The Doctrine of God: The Election of God; The Command of God, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09022-1, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05179-X (German: 1942)

- Volume III Part 1: The Doctrine of Creation: The Work of Creation, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09031-0, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05079-3 (German: 1945)

- Volume III Part 2: The Doctrine of Creation: The Creature, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09032-9, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05089-0 (German: 1948)

- Volume III Part 3: The Doctrine of Creation: The Creator and His Creature, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09033-7, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05099-8 (German: 1950)

- Volume III Part 4: The Doctrine of Creation: The Command of God the Creator, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09034-5, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05109-9 (German: 1951)

- Volume IV Part 1: The Doctrine of Reconciliation, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09041-8, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05129-3 (German: 1953)

- Volume IV Part 2: Doctrine of Reconciliation: Jesus Christ the Servant As Lord, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09042-6, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05139-0 (German: 1955)

- Volume IV Part 3, first half: Doctrine of Reconciliation: Jesus Christ the True Witness, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09043-4, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05189-7 (German: 1959)

- Volume IV Part 3, second half: Doctrine of Reconciliation: Jesus Christ the True Witness, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09044-2, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05149-8 (German: 1959)

- Volume IV Part 4 (unfinished): Doctrine of Reconciliation: The Foundation of the Christian Life (Baptism), hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09045-0, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05159-5 (German: 1967)

- Volume V: Church Dogmatics: Contents and Indexes, hardcover: ISBN 0-567-09046-9, softcover: ISBN 0-567-05119-6

- Church Dogmatics, 14 volume set, softcover, ISBN 0-567-05809-3

- Church Dogmatics: A Selection, with intro. by H. Gollwitzer, 1961, Westminster John Knox Press 1994, ISBN 0-664-25550-7

- Church Dogmatics, dual language German and English, books with CD-ROM, ISBN 0-567-08374-8

- Church Dogmatics, dual language German and English, CD-ROM only, ISBN 0-567-08364-0

Audio

- Evangelical Theology, American lectures 1962 – given by Barth in Chicago, Illinois and Princeton, New Jersey, ISBN 978-0-9785738-0-5 and ISBN 0-9785738-0-3

https://www.christamongthedisciplines.com/

by R.E. SlaterNovember 23, 2020Please note: I write these notes to myself. They are not intended to be exact transcriptions from the speakers themselves. What I have written are not their words but my own thoughts. - resPlease note: All panelists provided textual statements for comments to attendees. These are not allowed to be publically published as they are intended to form to the moment-in-time not replicable beyond the panel discussions themselves as very specific conversations to one another in the AAR setting