- Lacan's central idea is that the unconscious is not just a repository of repressed desires but is structured like language, which means it can be systematically analyzed.

- "The Other": In Lacanian theory, human desire is the "desire of the Other," meaning it is a desire for recognition and is shaped by what others desire.

- The Mirror Stage: A concept describing the moment a child recognizes its own reflection, which is crucial for forming the ego and a sense of a unified self.

- The Three Registers: Lacan used the concepts of the imaginary (images and relationships), the symbolic (language and law), and the real (what is unsymbolized) to describe human experience.

- Lacan's approach to psychoanalysis uses techniques such as free association and dream analysis to explore a patient's linguistic patterns and symbols. The goal is to bring unconscious processes into conscious awareness and challenge societal norms to understand one's own authentic desires.

- His work has been highly influential, particularly within Continental philosophy and various humanities disciplines. He was also a key figure in 20th-century French intellectual life and had a complex relationship with the psychoanalytic community, famously leading to his excommunication from the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA).

- Key Concepts: His metaphysics centers on "actual occasions" or "actual entities" as the fundamental elements of reality, which are moments of experience that constantly "prehend" (incorporate) the past to create novel future events.

- Focus: Whitehead's work is an attempt to conceptualize existence at a cosmic level, emphasizing relationality, the role of feeling, and the emergence of value in the universe. His 1927 book, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect, focuses on perception and language as acts of symbolization.

- Tradition: He is generally associated with the realist tradition and American pragmatism.

- Key Concepts: His work revolves around the tripartite ontology of the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary orders.

- The Imaginary is the realm of images, identity, and identification.

- The Symbolic is the order of language, law, and social structures that introduces "lack" into the subject.

- The Real is that which resists symbolization and imagination.

- Focus: Lacan is concerned with the subject of science and the construction of human subjectivity within language, rather than the objects of scientific study.

- Symbolism and the Signifier/Signified: Scholars have compared Whitehead's and Lacan's approaches to symbolism. One analysis suggests that Whitehead's view of symbolism, which questions the fixed binary of signifier/signified, poses a fundamental challenge to Lacan's theory, where the signifier always "slips" and points elsewhere. Whitehead allows for images to signify words and vice versa, a flexibility that contrasts with Lacan's more rigid structuralist framework in which the signifier dominates.

- Metaphysics and Subjectivity: While Lacanian theory concerns knowledge and the unconscious subject, Whitehead's theory attempts to conceptualize the existence and feeling of all entities in the cosmos.

- Poststructuralism: Whitehead's process philosophy has been explored for its potential influence on contemporary poststructuralism (e.g., Deleuze), a school of thought that also engages heavily with Lacanian psychoanalysis.

Today I finished reading “Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect” by Alfred North Whitehead. In this essay, I plan to present the main ideas from his book, their implications, as well as how I think they can relate to the work of other thinkers like Lacan, Hegel, Lacan or Deleuze.

Whitehead defines symbolism as the process through which certain components of a subject’s experience elicit “consciousness, beliefs, emotions, and usages, respecting other components of its experience”¹. The former are what Whitehead calls “symbols” while the latter are what Whitehead calls “meaning”. ‘Symbolic reference’ is thus defined as the way in which one aspect of our experience elicits or triggers another aspect of our experience.

What is to be first pointed out is the way in which Whitehead overturns the traditional signifier/signified relationship from traditional structural linguistics. For Whitehead, any aspect of our experience can symbolize another aspect. Thus, just like a word can symbolize an image, so can an image symbolize a word. Whitehead gives the example of a poet: “if you are a poet and wish to write a lyric on trees, you will walk into the forest in order that the trees may suggest the appropriate words. Thus for the poet, the trees are the symbols and the words are the meaning. He concentrates on the trees in order to get at the words.”²

In traditional semiotics, we accustomed to think of words as signifiers and images as signifieds. This is the basis upon which Lacan forms his theory of the imaginary and the symbolic order. For Lacan, the symbolic order is composed of signifiers and the imaginary order of signifieds. But Whitehead questions this binary: why can’t an image signify a word? For a poet, the image of a tree brings up lyrics about trees, so it is surely possible.

We need to rigorously analyze the profound implications this has upon Lacan’s theory. For Lacan, the imaginary order is the order of identity and identification, where every component (signified) is equal to itself. The symbolic order is what introduces lack into the subject by way of which each signifier is a contradiction, since it is not equal to itself. ‘A signifier is that which is the subject for another signifier’, as Lacan said. The signifier always “slips” for Lacan, it points to somewhere else. The signifier always means something else other than itself (with the exception of the master-signifier, which is self-referential).

Whitehead would be tempted to question the very division between imaginary and symbolic. For Whitehead, anything can be a symbol (“signifier”) and anything can be a meaning (“signified”). Whitehead says: “The nature of their [the symbol and the meaning] relationship does not in itself determine which is symbol and which is meaning. There are no components of experience which are only symbols or only meanings”³.

Since any component of our experience points towards other components, thus any component of our experience having the potential to be a symbol (signifier), Whitehead may be tempted to deny the existence of the imaginary order altogether. This is related to him being the main representant of the philosophical movement known as “process philosophy”, the view that reality is a flux in constant change and becoming. For Whitehead, our experience is constantly moving and changing, and each component of our experience will automatically trigger other components of our experience, thus acting as a symbol. The existence of such a thing as the imaginary order would be a fallacy in our reasoning based on our a priori false assumption that there can ever be anything that is static and fixed, that does not point to something else. The image of a tree is not just a signified, we showed how it can very well signify the word ‘tree’ just as the word can signify the image. The signifying chain thus never stops, it is a process in a continuous state of becoming: meaning is perpetually deferred, with each new ‘signified’ acting as a signifier for the next triggered component of our experience.

Another flawed assumption of what Deleuze may have called our ‘common sense’ is that symbolization is a mathematical function, where a certain input (symbol) always leads to a single output (meaning). In other words, our common sense is tempted to assume that something can only mean one thing, that a symbol can not refer to multiple things at the same time. But Whitehead refutes this assumption in his analysis of the relationship between speech and writing:

“Often the written word suggests both the spoken word and also the meaning, and the symbolic reference is made clearer and more definite by the additional reference of the spoken word to the same meaning. Analogously we can start from the spoken word which may elicit a visual perception of the written word.”⁴

Whitehead suggests that a spoken word can signify both its written version and its associated image, just like a written word can signify both its spoken version and its associated image. And why can’t the image signify both the written and the spoken word? Thus we see how one symbol can have two (or more) meanings attached to it.

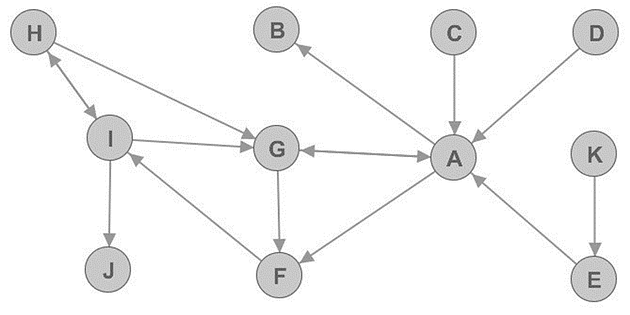

This forces us to rethink the very way we can visualize signifying chains. We aren’t dealing with straight lines, as we would if we were dealing with a 1-to-1 mathematical function. Nor are we dealing with a sort of tree, as we would if we were dealing with a mathematical function that is not 1-to-1. Instead, we aren’t dealing with a function at all, but instead with what in math is known as a multi-function, where not only can the same output have multiple inputs, but one single input can have multiple outputs. Our computer science analogy is thus neither a linked list, nor a binary tree, but a directed graph:

We can use the image above as a visual analogy for how symbolism works for Whitehead. In it, each letter is either a symbol, a meaning or both. It is a symbol if an arrow points out of it and a meaning if an arrow points into it. For example, A is a symbol for B and B is a meaning for A. But H and I are both symbols and meanings for each other. And H has two different meanings: G and I.

This view of language is rhizomatic, in the spirit of Deleuze and Guattari. In “A Thousand Plateaus”, D&G critique Chomsky’s hierarchical model of language, instead providing as an alternative a non-hierarchical, rhizomatic model for how language and meaning in general operate.

But symbolism does not stop at language. For Whitehead, perception itself is a form of symbolic reference. This is in contrast to [the philosopher] Hegel, who viewed perception as a sublation of sense-certainty. The difference between sense-certainty and perception is that sense-certainty provides a flux of unmediated, ‘unprocessed’ and chaotic sense data, the unfiltered flux of sense information that is coming in through our five senses. Perception, on the other hand, implies the work of reason and memory as well in order to “make sense” of that sense data. For example, when I look next to me, I see a blob of colors in various shapes and sizes, this is sense-certainty. But I engage not in sense-certainty, but in perception, when I look at that undifferentiated chaos of colors and shapes and I say “this is a chair!”. The act of perceiving a chair implies classifying and labelling an input of sense-data into a certain category that I can recall through memory.

For Hegel, perception evolves out of the sublation of sense-certainty. For Whitehead, on the other hand, it is sense-certainty which is a symbol for perception. Thus, just as the word ‘tree’ can symbolize the image of the tree, or how the image of the tree can symbolize the word ‘tree’ for the poet, so does sense-certainty symbolize perception, since it is one component of our experience triggering another.

Whitehead divides experience into two types: presentational immediacy and causal efficacy. Presentational immediacy refers to the vivid, immediate sensory experience of the external world, as mediated through sense-data (such as colors, shapes, sounds, etc.). Causal efficacy refers to the perception of how past or present events influence the present experience, emphasizing the underlying forces or relations shaping reality. Presentational immediacy is static and fixed, it provides us an image of the present outside of temporal relations. Causal efficacy is at the basis of Whitehead’s process philosophy since it puts the present moment in relation to the past, as an effect resulting from a different event in the past.

Thus, we can distinguish between four types of symbolic reference:

1. From presentational immediacy to another presentational immediacy (association)

2. From causal efficacy to another causal efficacy (reason)

3. From presentational immediacy to causal efficacy (perception)

4. From causal efficacy to presentational immediacy (imagination, memory, etc.)

Thus perception (the third one) is only one type of symbolic reference, where our presentational immediacy (sense data, or what Hegel called “sense-certainty”) refers to, or symbolizes, the causal relationship between that sense data and the object in our experience that triggered it. But we are just as justified in thinking that causal efficacy itself can trigger a form of presentational immediacy: for example, in the acts of imagination and memory. In these cases, an image in the mode of causal efficacy (for example, the way the rain touches your skin) triggers an image in the mode of presentational immediacy (for example, a memory of how you liked rain as a child): only the latter here is a ‘thing’, the former that triggered it is a relationship between things. Thus, Whitehead implicitly challenges Hegel’s teleological and linear development in The Phenomenology of Spirit (although without mentioning his name). Just as Hegel goes from presentational immediacy to causal efficacy in the creation of the concept of perception, we are just as justified in going backwards: from perception back to sense-data.

While Whitehead does not mention Hegel in his book, he does mention Hume and Kant with the purpose of critiquing them. Whitehead mentions how Hume and Kant were anti-realists in regards to causal efficacy, assuming that causal efficacy is either an effect of habituation (Hume) or a product of our mind’s categories (Kant). But Whitehead insists that causal efficacy is in fact the default mode of experience, and that presentational immediacy requires an active effort of our mind, not the other way around. Whitehead gives the example of the perception of a chair: “We look up and see a coloured shape in front of us, and we say, — there is a chair. But what we have seen is the mere coloured shape”⁵. Whitehead mentions how a trained painter may not have immediately jumped to the perception of a chair, and may have instead remained in the mode of presentational immediacy to observe the colors: “He might have stopped at the mere contemplation of a beautiful colour and a beautiful shape”⁶. Whitehead explains that “my friend the artist, who kept himself to the contemplation of colour, shape and position, was a very highly trained man, and had acquired this facility of ignoring the chair at the cost of great labour”⁷. For Whitehead, remaining at the level of presentational immediacy without triggering the mode of causal efficacy through the act of perception requires an active effort from the part of the subject. It is in the subject’s instinct to engage in perception and thus move to the mode of causal efficacy. Whitehead gives the example of a dog as well: “if we had been accompanied by a puppy dog, in addition to the artist, the dog would have acted immediately on the hypothesis of a chair and would have jumped onto it by way of using it as such. Again, if the dog had refrained from such action, it would have been because it was a welltrained dog”⁸.

In the spirit of process philosophy, Whitehead views everything as relational: the present can only be analyzed in relation to its history. Whitehead thus demonstrates how presentational immediacy is not in our ‘natural instinct’ when it comes to not only humans, but to animals and plants as well. When a sunflower moves itself to face the sun, it does not engage in the mode of presentational immediacy to form a static and fixed image of how reality is in the present, instead it reacts to the environment, engaging in an act of perception, instinctively moving from presentational immediacy to causal efficacy. The opposite act, when we move from causal efficacy to presentational immediacy (as we do in the acts of imagination or memory) require a more conscious effort, the repression of our instincts, and thus exist only in more advanced organisms such as humans, being more limited in plants and animals.

Whitehead uses this insight to critique Hume’s anti-realism towards causality. Hume treats sense-data (impressions) as the sole foundation of perception, dismissing any intrinsic connection to external causality. Hume denies that impressions can demonstrate the “real existence” or causal relations of objects, seeing causality as a habit of thought rather than an immediate perception. Whitehead argues that this dismissal rests on a faulty assumption that sense-data exist in isolation. He posits that causal efficacy — our perception of the influence and conformity of the present to the past — is an integral and direct component of experience, not a secondary habit or category, present even in animals and plants.

The final thing I want to point out that stuck in my mind after reading his book is Whitehead’s insistence on immanence. In the spirit of Gilles Deleuze, Whitehead also rejects looking for sense in the ‘depths’ or in the ‘heights’, as Deleuze would have put it. For Deleuze, sense is a surface effect. Whitehead, in a similar fashion, defines symbolism as the act of purely going from one content of our experience to another, rejecting the symbolization of transcendental concepts that we can not experience such as “God”. For Whitehead, an image can symbolize a word, a word can symbolize an image, an image can symbolize another image, a word can symbolize another word, a written word a spoken word, etc.; but all these examples are examples in which one aspect of our phenomenological, conscious experience refers back to another aspect of it. There is no unreachable “noumenon”, as in Kant’s transcendental idealism; nor a Kantian division between ‘understanding’ and ‘reason’, where only the latter symbolizes concepts outside of our immediate experience. Instead, Whitehead’s symbolism is grounded in the immediacy of lived experience, where meaning arises through relational processes within the flow of reality itself. By refusing to posit a hidden depth or transcendent beyond, Whitehead invites us to view sense-making as an emergent, immanent activity that remains fully embedded in the world of experience.

----

REFERENCES:

1: Alfred North Whitehead, “Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect”, pg. 8

2: ibid., pg. 12

3: ibid., pg. 10

4: ibid., pg. 11

5: ibid., pg. 2

6: ibid., pg. 3

7: ibid.

8: ibid., pg. 4