|

| click to enlarge |

Occasionally I like to update myself and Christian readers with developments in the anthropological world of human evolution. I find it helpful to remember how the human species fits in with the larger evolutionary history of the world as we push forward into a number of areas including:

1. Cosmo-evolutionary societies and civilizations2. Process-based evolutionary thought, and when3. Reading of the Genesis story in the bible.

All of which are to remind us that God, creation, man, sin, and salvation have actual theological roots in the process world of evolution:

- That when reading the bible we need to remind ourselves that a literal reading of Hebraic legends are not factual but are culturally constructed narratives through recitation of oral histories at the time giving that part of the Semetic world its own separate identity of who they are and where they are going.

- That we we cannot dismiss the "process complexity" of evolutionary creation but that we can praise God who created us and the heavens around us for the wonder of its beauty and novelty set within a highly relational cosmos.

- And lastly, that when discussing origins, or free will agency, in process theological terms that biblical observations of sin and temptation are no less than what they are in the real world. That a process-based creation strives within itself to be in fellowship with its Creator God at all times even as it exercise agency at all times.

Yes, the language changes but not the concepts. The forms change but not the observations that Christ came into this world to save us not only from our sins BUT that creation and man become fully who we were made to be in the fullness of the Godhead. In God's beauty and love, wholeness and fellowship.

In these observations then a process-based world of evolution is no less biblical than the Hebraic world of creational stories meant to provide godly (theistic) identity, wellbeing, and purpose. Each projection attempts to achieve the same ends regardless of the temporal society it was spoken in.

Blessings,

R.E. Slater

April 2, 2021

As an aside, I posted this article on Good Friday of Easter Weekend. In my comments I would like to remind fellow Christians of the following truths:"Today is Good Friday and the start of Easter Weekend. What better time to explore man's evolutionary origins than now. The Christian observation of salvific "Death and Resurrection" is as true now as it was at the creation of the heavens and earth by the Lord God of Creation. Cosmic, Geologic, and Biologic death and resurrection are all process pictures of Christ's death and resurrection. All of salvation history is written in terms of death and resurrection. As in evolutionary history so too in God's usage of death and resurrection in the life of Jesus. Who is Savior no less to man than He is to all of creation. The cycles (motifs) of death and resurrection are important process cycles all creation is familiar with. It was from within the very processes themselves wherein God gave new hope to all things living and non-living. That creation may rejoin with its purpose of loving wellbeing, novelty, and reformation forever and ever and ever because of Jesus' death and resurrection which we remember this weekend." - re slater

* * * * * * * * *

HELPFUL ILLUSTRATIONS

* * * * * * * * *

|

| click to enlarge |

* * * * * * * * *

New discoveries fundamentally change the

picture of human evolution in Africa

by Katie Hunt, CNN

Wed March 31, 2021

Archaeological excavations at Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter, where crystals and other early evidence for complex behaviors among early Homo sapiens was discovered:

(CNN)The story of humankind's origins was thought to have largely unfolded in a cave with a sea view.

The earliest evidence suggesting that modern humans were capable of symbolic thought and complex behavior -- the use of ochre pigments paint and decorative items -- comes from coastal sites in Africa that date back to around 70,000 to 125,000 years ago. These types of objects give us insights into the human mind because they suggest a shared identity.

Archeologists had assumed that many of the innovations and skills that make Homo sapiens unique evolved in groups living by the coast before spreading inland. Predictable marine resources like shell fish and a more forgiving climate may have allowed more early humans in these areas to thrive. Plus a diet rich in sea food, which contains omega-3 fatty acids that are important for brain growth, may also have played a role in the evolution of the brain and human behavior.

However, new discoveries 600 kilometers (about 370 miles) inland in the southern Kalahari Desert contradict that view, and a new study suggests that early modern humans living in this region did not lag behind their counterparts living on the coast.

Some 22 calcite crystals and fragments of ostrich shell -- found in the Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter in South Africa and dated to approximately 105,000 years ago -- are thought to have been deliberately collected and brought to the site. The crystals serve no obvious purpose, and the researchers suggested that the ostrich shells could have been used as a water bottle.

"They're really well-formed, white and visually striking and lovely. Crystals around the world are really important for spiritual and ritual reasons in different time periods and different places," said Jayne Wilkins, a palaeoarchaeologist at the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution at Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, and lead author of the study that published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

"We tried really hard to find out whether or not natural processes could explain how they got into the archeological deposits but there isn't an explanation. People must have brought them to the site."

Wilkins said that in light of these findings, ideas linking the emergence of Homo sapiens and coastal environments "needed to be rethought." She suggested that humans' origin story was more complex, involving different places and environments in Africa and different groups of early people interacting with one another and contributing to the emergence of our species.

"Before this, the Kalahari was not considered an important region for understanding the origins of complex Homo sapiens behaviors, but our work shows that it is. Ultimately, this means that models that focus on one single origin center, like the coast of South Africa, are too simplistic," she told CNN in an email.

Pamela Willoughby, a professor in the anthropology department at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, who was not involved in the research, agreed with this assessment.

A calcite crystal being excavated from 105,000-year-old deposits at Ga-Mohana Hill North Rockshelter.

"The objects they found suggest it is time to revise current thinking about the emergence of cultural innovations among early human populations," she said in a commentary that was published alongside the study.

The climate in the Kalahari 100,000 years ago would have been much different than the arid place it is now.

The newly uncovered artifacts would have been in human hands at a time of increased rainfall. The researchers said that the greater availability of water might have led to greater population densities, which could have influenced the origin and spread of innovative behavior.

Willoughby said that part of the problem in untangling the complex story of human origins is that only a few African regions have been studied in detail.

She said that the fossil record in Africa "now indicates that there does not seem to be any single pattern of technological and social development over time. Initiating surveys and excavations of lesser-known areas will help to clarify what it was that made our immediate ancestors truly modern, both biologically and culturally."

* * * * * * * * *

RELATED ARTICLES

* * * * * * * * *

Australopithecus (/ˌɒstrələˈpɪθɪkəs/, OS-trə-lə-PITH-i-kəs;[1] from Latin australis 'southern', and Greek πίθηκος (pithekos) 'ape'; singular: australopith) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genera Homo (which includes modern humans), Paranthropus, and Kenyanthropus evolved from Australopithecus. Australopithecus is a member of the subtribe Australopithecina,[2][3] which also includes Ardipithecus,[4] though the term "australopithecine" is sometimes used to refer only to members of Australopithecus. Species include A. garhi, A. africanus, A. sediba, A. afarensis, A. anamensis, A. bahrelghazali and A. deyiremeda. Debate exists as to whether some Australopithecus species should be reclassified into new genera, or if Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus are synonymous with Australopithecus, in part because of the taxonomic inconsistency.[5][6]

The earliest known member of the genus, A. anamensis, existed in eastern Africa around 4.2 million years ago. Australopithecus fossils become more widely dispersed throughout eastern and southern Africa (the Chadian A. bahrelghazali indicates the genus was much more widespread than the fossil record suggests), before eventually becoming extinct 1.9 million years ago (or 1.2 to 0.6 million years ago if Paranthropus is included). While none of the groups normally directly assigned to this group survived, Australopithecus gave rise to living descendants, as the genus Homo emerged from an Australopithecus species[5][7][8][9][10] at some time between 3 and 2 million years ago.[11]

Australopithecus possessed two of three duplicated genes derived from SRGAP2 roughly 3.4 and 2.4 million years ago (SRGAP2B and SRGAP2C), the second of which contributed to the increase in number and migration of neurons in the human brain.[12][13] Significant changes to the hand first appear in the fossil record of later A. afarensis about 3 million years ago (fingers shortened relative to thumb and changes to the joints between the index finger and the trapezium and capitate).[14]

Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Suborder: Haplorhini Infraorder: Simiiformes Parvorder: Catarrhini Superfamily: Hominoidea Family: Hominidae

Apes (Hominoidea /hɒmɪˈnɔɪdiːə/) are a branch of Old World tailless simians native to Africa and Southeast Asia. They are the sister group of the Old World monkeys, together forming the catarrhine clade. They are distinguished from other primates by a wider degree of freedom of motion at the shoulder joint as evolved by the influence of brachiation. In traditional and non-scientific use, the term "ape" excludes humans, and can include tailless primates taxonomically considered monkeys (such as the Barbary ape and black ape), and is thus not equivalent to the scientific taxon Hominoidea. There are two extant branches of the superfamily Hominoidea: the gibbons, or lesser apes; and the hominids, or great apes.

- The family Hylobatidae, the lesser apes, include four genera and a total of sixteen species of gibbon, including the lar gibbon and the siamang, all native to Asia. They are highly arboreal and bipedal on the ground. They have lighter bodies and smaller social groups than great apes.

- The family Hominidae (hominids), the great apes, include four genera comprising three extant species of orangutans and their subspecies, two extant species of gorillas and their subspecies, two extant species of panins (bonobos and chimpanzees) and their subspecies, and one extant species of humans in a single extant subspecies.[1][a][2][3]

Except for gorillas and humans, hominoids are agile climbers of trees. Apes eat a variety of plant and animal foods, with the majority of food being plant foods, which can include fruit, leaves, stalks, roots and seeds, including nuts and grass seeds. Human diets are sometimes substantially different from that of other hominoids due in part to the development of technology and a wide range of habitation. Humans are by far the most numerous of the hominoid species, in fact outnumbering all other primates by a factor of several thousand to one.

Most non-human hominoids are rare or endangered. The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat. The great apes of Africa are also facing threat from the Ebola virus. Currently considered to be the greatest threat to survival of African apes, Ebola infection is responsible for the death of at least one third of all gorillas and chimpanzees since 1990.[4]

In the early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, there were many species of arboreally adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa; the variety suggests a long history of prior diversification. Fossils at 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

At sites far distant from East Africa, the presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids, that is, non-monkey primates, of middle Miocene age—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is further evidence of a wide diversity of ancestral ape forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the early and middle Miocene. The most recent of these far-flung Miocene apes (hominoids) is Oreopithecus, from the fossil-rich coal beds in northern Italy and dated to 9 million years ago.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons (family Hylobatidae), the "lesser apes", diverged from that of the great apes some 18–12 million years ago, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years. There are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a still-unknown South East Asian hominoid population; but fossil proto-orangutans, dated to around 10 million years ago, may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey.[10] Species close to the last common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans may be represented by Nakalipithecus fossils found in Kenya and Ouranopithecus found in Greece. Molecular evidence suggests that between 8 and 4 million years ago, first the gorillas (genus Gorilla), and then the chimpanzees (genus Pan) split off from the line leading to the humans. Human DNA is approximately 98.4% identical to that of chimpanzees when comparing single nucleotide polymorphisms (see human evolutionary genetics).[11] The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation—rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone—and sampling bias probably contribute most to this problem.

Other hominins probably adapted to the drier environments outside the African equatorial belt; and there they encountered antelope, hyenas, elephants and other forms becoming adapted to surviving in the East African savannas, particularly the regions of the Sahel and the Serengeti. The wet equatorial belt contracted after about 8 million years ago, and there is very little fossil evidence for the divergence of the hominin lineage from that of gorillas and chimpanzees—which split was thought to have occurred around that time. The earliest fossils argued by some to belong to the human lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma), followed by Ardipithecus (5.5–4.4 Ma), with species Ar. kadabba and Ar. ramidus.

TAXONOMY

Terminology

The classification of the great apes has been revised several times in the last few decades; these revisions have led to a varied use of the word "hominid" over time. The original meaning of the term referred to only humans and their closest relatives—what is now the modern meaning of the term "hominin". The meaning of the taxon Hominidae changed gradually, leading to a modern usage of "hominid" that includes all the great apes including humans.

A number of very similar words apply to related classifications:

- A hominoid, sometimes called an ape, is a member of the superfamily Hominoidea: extant members are the gibbons (lesser apes, family Hylobatidae) and the hominids.

- A hominid is a member of the family Hominidae, the great apes: orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans.

- A hominine is a member of the subfamily Homininae: gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans (excludes orangutans).

- A homininan, following a suggestion by Wood and Richmond (2000), would be a member of the subtribe Hominina of the tribe Hominini: that is, modern humans and their closest relatives, including Australopithecina, but excluding chimpanzees.[13][14]

- A human is a member of the genus Homo, of which Homo sapiens is the only extant species, and within that Homo sapiens sapiens is the only surviving subspecies.

* * * * * * * * *

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera Homo (humans) and Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos), but excludes the genus Gorilla (gorillas).

The term was originally introduced by Camille Arambourg (1948). Arambourg combined the categories of Hominina and Simiina due to Gray (1825) into his new subtribe. This definition is still adhered to in the proposal by Mann and Weiss (1996), which divides Hominini into three subtribes, Panina (containing Pan), Hominina ("homininans", containing Homo "humans"), and Australopithecina (containing several extinct "australopithecine" genera).[2]

Alternatively, Hominini is taken to exclude Pan. In this case, Panini ("panins", Delson 1977)[3] may refer to the tribe containing Pan as its only genus.[4][5] Or perhaps place Pan with other dryopithecine genera, making the whole tribe or subtribe of Panini or Panina together.

Minority dissenting nomenclatures include Gorilla in Hominini and Pan in Homo (Goodman et al. 1998), or both Pan and Gorilla in Homo (Watson et al. 2001).

Terminology and definition

Further information: Human taxonomy

By convention, the adjectival term "hominin" (or nominalized "hominins") refers to the tribe Hominini, while the members of the subtribe Hominina (and thus all archaic human species) are referred to as "homininan" ("homininans").[6] This follows the proposal by Mann and Weiss (1996), which presents tribe Hominini as including both Pan and Homo, placed in separate subtribes. The genus Pan is referred to subtribe Panina, and genus Homo is included in the subtribe Hominina (see above).[2] However, there is an alternative convention which uses "hominin" to exclude members of Panina, i.e. either just for Homo or for both human and australopithecine species. This alternative convention is referenced in e.g. Coyne (2009)[7] and in Dunbar (2014).[5] Potts (2010) in addition uses the name Hominini in a different sense, as excluding Pan, and uses "hominins" for this, while a separate tribe (rather than subtribe) for chimpanzees is introduced, under the name Panini.[4] In this recent convention, contra Arambourg, the term "hominin" is applied to Homo, Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, and others that arose after the split from the line that led to chimpanzees (see cladogram below);[8][9] that is, they distinguish fossil members on the human side of the split, as "hominins", from those on the chimpanzee side, as "not hominins" (or "non-hominin hominids").[7]

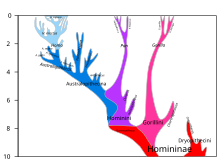

This cladogram shows the clade of superfamily Hominoidea and its descendent clades, focussed on the division of Hominini (omitting detail on clades not ancestral to Hominini). The family Hominidae ("hominids") comprises the tribes Ponginae (including orangutans), Gorillini (including gorillas) and Hominini, the latter two forming the subfamily of Homininae. Hominini is divided into Panina (chimpanzees) and Australopithecina (australopithecines). The Hominina (humans) are usually held to have emerged within the Australopithecina (which would roughly correspond to the alternative definition of Hominini according to the alternative definition which excludes Pan).

Genetic analysis combined with fossil evidence indicates that hominoids diverged from the Old World monkeys about 25 million years ago (Mya), near the Oligocene-Miocene boundary.[10] The most recent common ancestors (MRCA) of the subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae lived about 15 million years ago.[11] In the following cladogram, the approximate time the clades radiated newer clades is indicated in millions of years ago (Mya).

|

| click to enlarge |

Evolutionary history

Further information: Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor

Both Sahelanthropus and Orrorin existed during the estimated duration of the ancestral chimpanzee-human speciation events, within the range of eight to four million years ago (Mya). Very few fossil specimens have been found that can be considered directly ancestral to genus Pan. News of the first fossil chimpanzee, found in Kenya, was published in 2005. However, it is dated to very recent times—between 545 and 284 thousand years ago.[12] The divergence of a "proto-human" or "pre-human" lineage separate from Pan appears to have been a process of complex speciation-hybridization rather than a clean split, taking place over the period of anywhere between 13 Mya (close to the age of the tribe Hominini itself) and some 4 Mya. Different chromosomes appear to have split at different times, with broad-scale hybridization activity occurring between the two emerging lineages as late as the period 6.3 to 5.4 Mya, according to Patterson et al. (2006),[13] This research group noted that one hypothetical late hybridization period was based in particular on the similarity of X chromosomes in the proto-humans and stem chimpanzees, suggesting that the final divergence was even as recent as 4 Mya. Wakeley (2008) rejected these hypotheses; he suggested alternative explanations, including selection pressure on the X chromosome in the ancestral populations prior to the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA).[14]

Most DNA studies find that humans and Pan are 99% identical,[15][16] but one study found only 94% commonality, with some of the difference occurring in noncoding DNA.[17] It is most likely that the australopithecines, dating from 4.4 to 3 Mya, evolved into the earliest members of genus Homo.[18][19] In the year 2000, the discovery of Orrorin tugenensis, dated as early as 6.2 Mya, briefly challenged critical elements of that hypothesis,[20] as it suggested that Homo did not in fact derive from australopithecine ancestors.[21] All the listed fossil genera are evaluated for:

- probability of being ancestral to Homo, and

- whether they are more closely related to Homo than to any other living primate—two traits that could identify them as hominins.

Some, including Paranthropus, Ardipithecus, and Australopithecus, are broadly thought to be ancestral and closely related to Homo;[22] others, especially earlier genera, including Sahelanthropus (and perhaps Orrorin), are supported by one community of scientists but doubted by another.[23][24]

Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Suborder: Haplorhini Infraorder: Simiiformes Family: Hominidae Subfamily: Homininae Tribe: Hominini Genus: Homo

Homo (from Latin homō 'man') is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus Australopithecus that encompasses the extant species Homo sapiens (modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely related to modern humans (depending on the species), most notably Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The genus emerged with the appearance of Homo habilis just over 2 million years ago.[1] Homo, together with the genus Paranthropus, is probably sister to Australopithecus africanus, which itself had previously split from the lineage of Pan, the chimpanzees.[2][3]

Homo erectus appeared about 2 million years ago and, in several early migrations, spread throughout Africa (where it is dubbed Homo ergaster) and Eurasia. It was likely the first human species to live in a hunter-gatherer society and to control fire. An adaptive and successful species, Homo erectus persisted for more than a million years and gradually diverged into new species by around 500,000 years ago.[4]

Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) emerged close to 300,000 to 200,000 years ago,[5] most likely in Africa, and Homo neanderthalensis emerged at around the same time in Europe and Western Asia. H. sapiens dispersed from Africa in several waves, from possibly as early as 250,000 years ago, and certainly by 130,000 years ago, the so-called Southern Dispersal beginning about 70–50,000 years ago[6][7][8][9] leading to the lasting colonisation of Eurasia and Oceania by 50,000 years ago. Both in Africa and Eurasia, H. sapiens met with and interbred with[10][11] archaic humans. Separate archaic (non-sapiens) human species are thought to have survived until around 40,000 years ago (Neanderthal extinction), with possible late survival of hybrid species as late as 12,000 years ago (Red Deer Cave people).

Names and taxonomy

Main articles: Human taxonomy and Names for the human species

See Homininae for an overview of taxonomy.

The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being" or "man" in the generic sense of "human being, mankind".[a] The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus (1758).[13][b] Names for other species of the genus were introduced beginning in the second half of the 19th century (H. neanderthalensis 1864, H. erectus 1892).

Even today, the genus Homo has not been strictly defined.[15][16][17] Since the early human fossil record began to slowly emerge from the earth, the boundaries and definitions of the genus Homo have been poorly defined and constantly in flux. Because there was no reason to think it would ever have any additional members, Carl Linnaeus did not even bother to define Homo when he first created it for humans in the 18th century. The discovery of Neanderthal brought the first addition.

The genus Homo was given its taxonomic name to suggest that its member species can be classified as human. And, over the decades of the 20th century, fossil finds of pre-human and early human species from late Miocene and early Pliocene times produced a rich mix for debating classifications. There is continuing debate on delineating Homo from Australopithecus—or, indeed, delineating Homo from Pan, as one body of scientists argues that the two species of chimpanzee should be classed with genus Homo rather than Pan. Even so, classifying the fossils of Homo coincides with evidence of: (1) competent human bipedalism in Homo habilis inherited from the earlier Australopithecus of more than four million years ago, as demonstrated by the Laetoli footprints; and (2) human tool culture having begun by 2.5 million years ago.

From the late-19th to mid-20th centuries, a number of new taxonomic names including new generic names were proposed for early human fossils; most have since been merged with Homo in recognition that Homo erectus was a single species with a large geographic spread of early migrations. Many such names are now dubbed as "synonyms" with Homo, including Pithecanthropus,[18] Protanthropus,[19] Sinanthropus,[20] Cyphanthropus,[21] Africanthropus,[22] Telanthropus,[23] Atlanthropus,[24] and Tchadanthropus.[25][26]

Classifying the genus Homo into species and subspecies is subject to incomplete information and remains poorly done. This has led to using common names ("Neanderthal" and "Denisovan"), even in scientific papers, to avoid trinomial names or the ambiguity of classifying groups as incertae sedis (uncertain placement)—for example, H. neanderthalensis vs. H. sapiens neanderthalensis, or H. georgicus vs. H. erectus georgicus.[27] Some recently extinct species in the genus Homo are only recently discovered and do not as yet have consensus binomial names (see Denisova hominin and Red Deer Cave people).[28] Since the beginning of the Holocene, it is likely that Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) has been the only extant species of Homo.

John Edward Gray (1825) was an early advocate of classifying taxa by designating tribes and families.[29] Wood and Richmond (2000) proposed that Hominini ("hominins") be designated as a tribe that comprised all species of early humans and pre-humans ancestral to humans back to after the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor; and that Hominina be designated a subtribe of Hominini to include only the genus Homo — that is, not including the earlier upright walking hominins of the Pliocene such as Australopithecus, Orrorin tugenensis, Ardipithecus, or Sahelanthropus.[30] Designations alternative to Hominina existed, or were offered: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002);[31][32][33] and later, Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003) proposed that the four genera Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Praeanthropus, and Sahelanthropus be grouped with Homo within Hominini (sans pan).[34]

Further information: Timeline of human evolutionSee Hominini and Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor for the separation of Australopithecina and Panina.

Australopithecus

Further information: Australopithecus

Several species, including Australopithecus garhi, Australopithecus sediba, Australopithecus africanus, and Australopithecus afarensis, have been proposed as the ancestor or sister of the Homo lineage.[35][36] These species have morphological features that align them with Homo, but there is no consensus as to which gave rise to Homo.

Especially since the 2010s, the delineation of Homo in Australopithecus has become more contentious. Traditionally, the advent of Homo has been taken to coincide with the first use of stone tools (the Oldowan industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the Lower Palaeolithic. But in 2010, evidence was presented that seems to attribute the use of stone tools to Australopithecus afarensis around 3.3 million years ago, close to a million years before the first appearance of Homo.[37] LD 350-1, a fossil mandible fragment dated to 2.8 Mya, discovered in 2015 in Afar, Ethiopia, was described as combining "primitive traits seen in early Australopithecus with derived morphology observed in later Homo.[38] Some authors would push the development of Homo close to or even past 3 Mya.[39] Others have voiced doubt as to whether Homo habilis should be included in Homo, proposing an origin of Homo with Homo erectus at roughly 1.9 Mya instead.[40]

The most salient physiological development between the earlier australopithecine species and Homo is the increase in endocranial volume (ECV), from about 460 cm3 (28 cu in) in A. garhi to 660 cm3 (40 cu in) in H. habilis and further to 760 cm3 (46 cu in) in H. erectus, 1,250 cm3 (76 cu in) in H. heidelbergensis and up to 1,760 cm3 (107 cu in) in H. neanderthalensis. However, a steady rise in cranial capacity is observed already in Autralopithecina and does not terminate after the emergence of Homo, so that it does not serve as an objective criterion to define the emergence of the genus.[41]

Homo habilis emerged about 2.1 Mya. Already before 2010, there were suggestions that H. habilis should not be placed in genus Homo but rather in Australopithecus.[42][43] The main reason to include H. habilis in Homo, its undisputed tool use, has become obsolete with the discovery of Australopithecus tool use at least a million years before H. habilis.[37] Furthermore, H. habilis was long thought to be the ancestor of the more gracile Homo ergaster (Homo erectus). In 2007, it was discovered that H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted for a considerable time, suggesting that H. erectus is not immediately derived from H. habilis but instead from a common ancestor.[44] With the publication of Dmanisi skull 5 in 2013, it has become less certain that Asian H. erectus is a descendant of African H. ergaster which was in turn derived from H. habilis. Instead, H. ergaster and H. erectus appear to be variants of the same species, which may have originated in either Africa or Asia[45] and widely dispersed throughout Eurasia (including Europe, Indonesia, China) by 0.5 Mya.[46]

Homo erectus

Main article: Homo erectus

Homo erectus has often been assumed to have developed anagenetically from Homo habilis from about 2 million years ago. This scenario was strengthened with the discovery of Homo erectus georgicus, early specimens of H. erectus found in the Caucasus, which seemed to exhibit transitional traits with H. habilis. As the earliest evidence for H. erectus was found outside of Africa, it was considered plausible that H. erectus developed in Eurasia and then migrated back to Africa. Based on fossils from the Koobi Fora Formation, east of Lake Turkana in Kenya, Spoor et al. (2007) argued that H. habilis may have survived beyond the emergence of H. erectus, so that the evolution of H. erectus would not have been anagenetically, and H. erectus would have existed alongside H. habilis for about half a million years (1.9 to 1.4 million years ago), during the early Calabrian.[47]

A separate South African species Homo gautengensis has been postulated as contemporary with Homo erectus in 2010.[48]

Phylogeny

A taxonomy of Homo within the great apes is assessed as follows, with Paranthropus and Homo emerging within Australopithecus (shown here cladistically granting Paranthropus, Kenyanthropus, and Homo).[49][50][3][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61] The exact phylogeny within Australopithecus is still highly controversial. Approximate radiation dates of daughter clades are shown in millions of years ago (Mya).[62] Graecopithecus, Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, possibly sisters to Australopithecus, are not shown here. Note that the naming of groupings is sometimes muddled as often certain groupings are presumed before a cladistic analyses is performed.[55]

|

| click to enlarge |

Several of the Homo lineages appear to have surviving progeny through introgression into other lines. Genetic evidence indicates an archaic lineage separating from the other human lineages 1.5 million years ago, perhaps H. erectus, may have interbred into the Denisovans about 55,000 years ago.[63][64][65][54][66][67] Fossil evidence shows Homo erectus s.s. survived at least until 117,000 yrs ago, and the even more basal Homo floresiensis survived until 50,000 years ago. Moreover, a thigh bone, dated at 14,000 years, found in a Maludong cave (Red Deer Cave people) strongly resembles very ancient species like early Homo erectus or the even more archaic lineage, Homo habilis, which lived around 1.5 million year ago.[68][69] A 1.5 million years Homo erectus-like lineage appears to have made its way into modern humans through the Denisovans and specifically into the Papuans and aboriginal Australians.[54] The genomes of non-sub-Saharan African humans show what appear to be numerous independent introgression events involving Neanderthal and in some cases also Denisovans around 45,000 years ago.[70][66] Likewise the genetic structure of sub-Saharan Africans seems to be indicative of introgression from a west Eurasian population some 3,000 years ago.[71][72]

Some evidence suggests that Australopithecus sediba could be moved to the genus Homo, or placed in its own genus, due to its position with respect to e.g. Homo habilis and Homo floresiensis.[56][73]

Dispersal

See also: Early expansions of hominins out of Africa, Interbreeding between archaic and modern humans, and Early human migrations

By about 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus is present in both East Africa (Homo ergaster) and in Western Asia (Homo georgicus). The ancestors of Indonesian Homo floresiensis may have left Africa even earlier.[74]

Homo erectus and related or derived archaic human species over the next 1.5 million years spread throughout Africa and Eurasia[75][76] (see: Recent African origin of modern humans). Europe is reached by about 0.5 Mya by Homo heidelbergensis.

Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens develop after about 300 kya. Homo naledi is present in Southern Africa by 300 kya.

H. sapiens soon after its first emergence spread throughout Africa, and to Western Asia in several waves, possibly as early as 250 kya, and certainly by 130 kya. In July 2019, anthropologists reported the discovery of 210,000 year old remains of a H. sapiens and 170,000 year old remains of a H. neanderthalensis in Apidima Cave, Peloponnese, Greece, more than 150,000 years older than previous H. sapiens finds in Europe.[77][78][79]

Most notable is the Southern Dispersal of H. sapiens around 60 kya, which led to the lasting peopling of Oceania and Eurasia by anatomically modern humans.[80] H. sapiens interbred with archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably with Neanderthals and Denisovans.[81]

Among extant populations of Homo sapiens, the deepest temporal division is found in the San people of Southern Africa, estimated at close to 130,000 years,[82] or possibly more than 300,000 years ago.[83] Temporal division among non-Africans is of the order of 60,000 years in the case of Australo-Melanesians. Division of Europeans and East Asians is of the order of 50,000 years, with repeated and significant admixture events throughout Eurasia during the Holocene.

Archaic human species may have survived until the beginning of the Holocene (Red Deer Cave people), although they were mostly extinct or absorbed by the expanding H. sapiens populations by 40 kya (Neanderthal extinction).

Hey,

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing this blog its very helpful to implement in our work

Regards.

Best Landscaping company in Delhi