Evangelicalism Is Dead!

Long Live Evangelicalism!

by Roger Olson

Link to - The Future of Evangelicalism, Part 2

Here is the second half of my presentation on “The Future of

Evangelicalism” at George Fox Evangelical Seminary on March 11.

The Future of Evangelicalism, Part II

Here is the second half of my presentation on “The Future of

Evangelicalism” at George Fox Evangelical Seminary on March 11.

The Future of Evangelicalism, Part II

A Lecture by Roger E. Olson

given at

George Fox Seminary

March 11, 2013

Part 2: The Evangelical Ethos and Postconservative Evangelicalism

Part 2: The Evangelical Ethos and Postconservative Evangelicalism

When I talk about “evangelicalism” as a present and future reality, I mean the evangelical ethos. The evangelical movement, as a cohesive coalition, is dead. It has dissolved into competing parties, each with its own expression of the evangelical ethos. To be sure, there still exists “evangelicalism” as an affinity group, but it is too large and too diverse to call a movement. The affinity is its ethos, but the affinity is too weak and admits too much opposition and competition to forge and cement a movement.

So what is the evangelical “ethos?” This is how I view David Bebbington’s and Mark Noll’s four hallmarks of evangelicalism. First, according to the two historians, evangelicals share “biblicism,” a general regard for Scripture as the uniquely inspired, written Word of God. I argue, however, that what’s unique about evangelical biblicism, as distinct from, say, confessional, Protestant orthodox biblicism, is love for the Bible. Evangelicals love the Bible as the story of God with us. Beyond the debates about its inerrancy or infallibility that divide evangelicals stands the experience of, in the words of Hans Frei, the Bible absorbing the world. Evangelicals are Christians who see the world through biblical lenses. So, evangelical biblicism is a distinctive kind of biblicism. It’s not just sola scriptura in a formal sense. It’s a very close, personal relationship with the Bible as God’s message to us, our means of knowing God in a personal, intimate way. The evangelical ethos encourages Bible reading for devotion as well as study; it motivates Bible memorization and a strong desire for everyone to have the Bible in their own language. In a word, evangelicals view the Bible’s main purpose as transformation, not just information.

So what is the evangelical “ethos?” This is how I view David Bebbington’s and Mark Noll’s four hallmarks of evangelicalism. First, according to the two historians, evangelicals share “biblicism,” a general regard for Scripture as the uniquely inspired, written Word of God. I argue, however, that what’s unique about evangelical biblicism, as distinct from, say, confessional, Protestant orthodox biblicism, is love for the Bible. Evangelicals love the Bible as the story of God with us. Beyond the debates about its inerrancy or infallibility that divide evangelicals stands the experience of, in the words of Hans Frei, the Bible absorbing the world. Evangelicals are Christians who see the world through biblical lenses. So, evangelical biblicism is a distinctive kind of biblicism. It’s not just sola scriptura in a formal sense. It’s a very close, personal relationship with the Bible as God’s message to us, our means of knowing God in a personal, intimate way. The evangelical ethos encourages Bible reading for devotion as well as study; it motivates Bible memorization and a strong desire for everyone to have the Bible in their own language. In a word, evangelicals view the Bible’s main purpose as transformation, not just information.Second, Bebbington and Noll identify conversionism as central to evangelicalism. The evangelical ethos is distinctive in the way it views salvation. In contrast to sacramental spirituality evangelicalism, as a spiritual ethos, believes that a right, reconciled, transforming relationship with God begins with a decision of repentance and faith. Evangelicals disagree about the nature of that decision, but all agree that authentic Christianity always includes begins with it. A process may precede it, whether that be irresistible grace regenerating and bending the person’s will or prevenient grace enabling acceptance of God’s saving grace. But that a person must repent and trust in Jesus Christ for authentic Christian life is part and parcel of evangelicalism as an ethos.

Third, Bebbington and Noll point to crucicentrism—cross-centered proclamation and devotion—as an essential hallmark of authentic evangelicalism. Evangelicals cling to the cross of Jesus Christ in faith. We sing about it. We preach it. We celebrate it. We re-enact it. Evangelicals disagree about theories of the atonement, although by far the majority of self-identified evangelicals have historically affirmed something like satisfaction or penal substitution or the governmental theory—all objective views of the atonement as having an effect on God and not just on people. The evangelical ethos is cross-centered.

Fourth, Bebbington and Noll regard activism in missions, evangelism and social transformation as essential to the evangelical ethos. Evangelicals have always been and are Christians who feel called to spread the gospel and help the poor and suffering. The evangelical ethos is marked by concern for the kingdom of God and its growth or approximation through divine-human cooperative effort in the world.

These are Bebbington’s and Noll’s four hallmarks, distinguishing features, of what I am calling the authentic evangelical ethos. In other words, “evangelical” is not merely “Protestant;” it is Protestantism energized with transforming personal experience of God.

To these four hallmarks I wish to add a fifth—respect for the Great Tradition of Christian orthodoxy especially as interpreted by the Reformation broadly defined (for example, to include the Anabaptists). Evangelicals always have been orthodox Protestant Christians in the sense of having a high Christology, embracing a trinitarian view of God, and believing in original sin and salvation through Christ alone, by grace alone, through faith alone. Evangelicals agree, however, that “saving faith” can never be merely notional; it always bears the fruit of Christ-centered discipleship, obedience and good works made possible by the indwelling, transforming Holy Spirit.

This ethos, marked by these five common features, “family resemblances, is alive and well. Unfortunately, those who share it tend to emphasize and underscore their differences about details such as the exact nature of biblical accuracy, whether it should be regarded as strict inerrancy or infallibility in matters of faith and practice. Other differences that divide those of us who share this ethos were mentioned in Part 1. There is no need to dwell on them here. Suffice it to say that it now seems unlikely, perhaps impossible, that these differences will allow reunion of evangelicals into a cohesive movement.

It seems to me that one great rift among evangelicals that has opened up in the last twenty-five to thirty years has to do with the authority of tradition. Reacting to perceived doctrinal drift among evangelicals (and others), some evangelical leaders have turned to tradition to shore up and reinforce evangelicalism’s identity. These evangelicals perceive an identity crisis within evangelicalism. They’re right, but in my opinion they are part of the problem. They end to regard right doctrine as the sine qua non of evangelical identity; for them, as for Carl Henry, the “dean” of evangelical theologians, at least in his later years, evangelicalism is primarily a mental category—defined by firm cognitive boundaries. As they perceive these boundaries loosening, these theologians and leaders influenced by them have appealed to one of two distinct visions of evangelical tradition and, as a result, I believe, hardened evangelical categories into a kind of rigid traditionalism that repels all creativity and reform.

One of these visions of evangelical tradition is sometimes called “paleo-orthodoxy.” Its champions have been and are Thomas Oden, Christopher Hall, and Daniel Williams. The gist of it is that Christians, including, of course evangelicals, are not free to interpret Scripture apart from and especially not against the ancient, ecumenical tradition of the church fathers. Oden has expressed this in many writings but most succinctly in The Rebirth of Orthodoxy (2003). Oden, Hall, and Williams all affirm sola scriptura as prima scriptura—Scripture above tradition. But they also argue that Scripture should never be separated from tradition or interpreted against it. By “tradition” they mean the catholic and orthodox tradition of the first seven to eight centuries.

The second traditionalism of conservative evangelicals is what some, including Millard Erickson, call the “received evangelical tradition.” Wayne Grudem offers a list of its exponents in his Systematic Theology. They include Hodge and Warfield and especially theologians who follow in their train—those who are faithful to the Old Princeton School of theology—almost all conservative Calvinists. This is a modern evangelical tradition perceived to be faithful to the reformers. The evangelicals of the Gospel Coalition are among those who seem to hold to the authority of this tradition as the hermeneutical litmus test for proper interpretation of Scripture.

So what’s the practical point of identifying these two evangelical traditionalisms? Just this: according to these conservative evangelicals, and to the moderate, conservative to centrist, mediating evangelicals sympathetic with them (I include in that category Mouw, George and Neff), authentic evangelical theology’s only tasks are critical and contextual. That is, theology’s task is to defend tradition and translate it into contemporary idioms. The constructive task of theology, then, is closed, finished. Doctrines are not to be revised.

Rarely do moderate, mediating evangelicals put it quite so starkly, but their reactions to evangelical attempts to revise traditional doctrines reveal their sympathies with evangelical traditionalists. Let’s look at two case studies.

The first case study is open theism. Open theism is the belief among evangelicals that the future is partly open, undetermined, and that even God does not know with absolute certainty events not yet determined by anyone or anything. Conservative evangelical traditionalists such as Oden and Al Mohler, the latter representing the “received evangelical tradition” group represented by the Gospel Coalition among others, have condemned open theism as heresy. Moderate, mediating theologians like George have labeled it a “deep deviation.” (Personal conversations). I conclude that, at least in some cases, these conservative and moderate evangelicals made up their minds against open theism before even studying it because it is non-traditional. Some of them have publicly stated that the weight of tradition is so against it that it isn’t even worthy of serious consideration. (I have had many sustained conversations with evangelical critics of open theism and my conclusion about this arises from those conversations.)

The second case study is N. T. Wright’s revisions of the traditional Reformed doctrine of justification by faith. This is spelled out in several articles and books but nowhere better than in Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision (IVP, 2009). There the British evangelical scholar concludes that justification is not the imputation of Christ’s righteousness on account of individual faith but the accounting of one as righteous, forgiven, based on inclusion in the people of God and “the faith of Jesus Christ.” But most importantly, it isn’t about individualized salvation at all; it is about the creation of God’s new family and the extending of God’s purposes into the wider world. (p. 248) As everyone knows who has been paying any attention to happenings in evangelical theology, Wright’s revisions have resulted in hysterical screaming from the conservatives—especially those associated with the Gospel Coalition. Much of that is in defense of tradition. “This is what we have always believed; don’t mess with it!”

Wright defends his revisionist project by saying “God has always more light and truth to break forth from his Holy Word. …. [i]f the light comes, and can be shown to come, from the Word, from Scripture itself, there is no tradition so strong, venerable or previously fruitful that it should not be prepared to learn from it.” (p. 249)

Open theism and Wright’s revision of the doctrine of justification are two examples of what I call “postconservative evangelicalism”—belief that the constructive task of theology is still open and ongoing and that no doctrine of tradition is so sacrosanct that it cannot be reconsidered and amended in light of fresh and faithful interpretation of Scripture.

Opponents of postconservative evangelicalism have often portrayed it as “worshiping the goddess of novelty” or following the lure of unfettered innovation. They make it sound like out-and-out liberal theology or at least, as John Piper accused me, of being on a “liberal trajectory.” I hadn’t even revised any doctrines! I had just defended some who have! That alone was enough for him to accuse me of incipient liberalism. I and other postconservatives like my late friend Stan Grenz have made abundantly clear to everyone who will listen that our source and norm for theological reconstruction is always Scripture. Yes, culture can be a guide, but not a norm. It helps us discover areas of Christian belief and practice that need attention. Contemporary science and philosophy are both emphasizing becoming over static being. Without doubt that contributed to postconservative attention to classical theism’s tendency to use the logic of perfection to expound and defend God’s absolute immutability. But postconservatives who are developing “relational theism” such as Tom Oord and LeRon Shults are not letting contemporary culture drive the changes; they are arguing that contemporary culture is inviting us, even propelling us, to interpret Scripture more correctly, shaking off the spells of Greek philosophical thinking such as the “logic of perfection,” to rediscover the personal side of God.

So, as I see it, something I call postconservative evangelicalism is a third major branch of contemporary and possibly future evangelicalism. The first is neo-fundamentalism. The second is moderate, conservative to centrist, mediating evangelicalism. Both, as I see it, tend to view doctrine as evangelicalism’s enduring essence and are to some extent captivated by tradition and unwilling to reconsider doctrines of Protestant orthodoxy. The main difference is that the moderate, centrist, mediating group is somewhat more generous in its orthodoxy, usually reluctant to label fellow evangelicals heretics. And they have a larger “tent,” so to speak, of evangelicals. For example, for them Anabaptists and Friends can be just as evangelical as conservative Baptists and Presbyterians.

So what is the future of this fractured former movement called evangelicalism? Again, I have to insist on the distinction between the ethos and the movement. The movement has no future that I can see. It is hopelessly broken into smaller groups, parties, movements of their own. Very little dialogue happens across the divides between them. For the most part, with very few exceptions, neo-fundamentalists only talk with each other. They may talk at other evangelicals, but they don’t even invite them to their meetings. (I was invited by a not-so-well-informed president of the Evangelical Theological Society to give a plenary address at its 2006 national meeting. When the executive committee, populated mainly by neo-fundamentalists heard of his invitation they forced him to withdraw it.) In 2004 Beeson Divinity School hosted a conference entitled “Pilgrims on the Sawdust Trail: Evangelical Ecumenism and the Quest for Christian Identity.” I was not invited, but I attended. All the speakers were, in my estimation, either fundamentalists, neo-fundamentalists, or moderate-mediating conservatives. Not one postconservative evangelical was invited to speak. When I politely challenged Oden’s public declaration that open theism is “just process theology” he told me to sit down and be quiet.

When I look at the future of evangelicalism I see only further fragmentation, unless we are looking at the evangelical ethos. I believe there is still a lot of life in it. And much of that is coming to us in North America from evangelicals in the Global South. But one thing that worries a lot of conservative, and perhaps also some progressive, postconservative evangelicals, is that most of these Global South evangelicals are strong believers in the miraculous, the supernatural, as normal and perhaps even normative for authentic Christian life. They don’t always fit the mold of traditional Pentecostalism, although sociologists of religion such as Philip Jenkins and Peter Berger tend to put them in that category. I would put them more in the category of “Third Wave Christianity” if we must use North American and Eurocentric categories. They insist on “signs and wonders” as essential to strong, vibrant evangelical faith.

Also, Global South evangelicals are not Americans; to a very large extent American evangelicalism has been stamped by American culture in ways we are not even aware of—unless Christians from other cultures tell us about it. American evangelicals are highly individualistic and consumer-oriented. We grow churches with secular marketing methods and feel perfectly free to “church shop” and start our own churches in entrepreneurial style. We mix American patriotic fervor with our Christianity. Evangelical theologian Peter Leithardt, in Between Babel and the Beast (Cascade, 2012) argues that something called “Americanism” has become a religion and we are exporting it to the rest of the world. Many evangelicals from Asia, Latin America and Africa, however, are resistant to it in ways we may find uncomfortable.

In my opinion, American evangelicalism has become so Western, so American, so modern, in the sense of Enlightenment based, that we have become a mission field for evangelicals from other parts of the world. And they are coming—to evangelize us for the gospel stripped of the cultural accretions we have put on and around it. To a very great extent, I believe, the future of evangelicalism in America depends on what we do with these missionaries to us. I recall one such encounter some years ago. Ugandan Bishop Festo Kivengere, a passionate evangelical, came to speak at the college where I then taught. Both in his talk and in lunch conversation with a select group of faculty he shared his concern for American evangelical Christianity and how Westernized it has become. His message was difficult for many to hear.

I believe that the future vitality and viability of the evangelical ethos in America will depend on our leaving behind the last vestiges of fundamentalism. I also believe that, unfortunately, those vestiges are growing in influence among us. Anti-science attitudes among evangelicals are deepening and spreading through the influence of home schooling and widespread anti-intellectualism. Evangelical crusades against science, whether evolution or global warming, are plunging us back into the 1920s and 1930s dark ages of evangelicalism. Evangelical heresy-hunting and name-calling are dividing us and causing outsiders, as well as many insiders, to think of evangelicals as intolerant and mean-spirited. Some evangelicals seem to thrive on controversy, patting each other on the back for exposing heterodoxy where it has previously gone unrecognized. Neo-fundamentalism is a real threat to the evangelical spirit.

On the other hand, I’m not much encouraged by some of the reactions to neo-fundamentalism. Many younger evangelicals are running as fast as they can and as far away as possible from doctrine, Bible study, evangelism, and anything that smacks of tradition. I do not regard the demise of hymn-singing among evangelicals as a good sign. Mark Noll is right that hymns and gospel songs are among evangelicals’ most important contributions to Christianity. Hymns such as Charles Wesley’s communicate the historic faith to congregations that otherwise never hear about doctrines. Much contemporary evangelical worship reminds me of Sunday School, youth group and camp when I was a child and teenager. The so-called emerging church movement worries as well as excites me. There’s energy and intensity there; the search for authenticity is praiseworthy. But too many among them are actively disinterested in historic Christian orthodoxy, the great doctrines of the faith, and also in the warm, experiential, heart-centered piety of traditional evangelicalism.

Somehow, if the evangelical spirit, the evangelical ethos, is going to survive and be “salt and light” in our world, we evangelicals have to overcome our petty squabbles, discover and build a new evangelical ecumenism, value our particularities without beating each other up over them, put secondary doctrinal, moral and ethical issues in the back seat where they belong, rediscover our spiritual heritage of Jesus-centered piety closely related to generous Christian orthodoxy, and recover from paranoia toward science and culture and every shred of triumphalism.

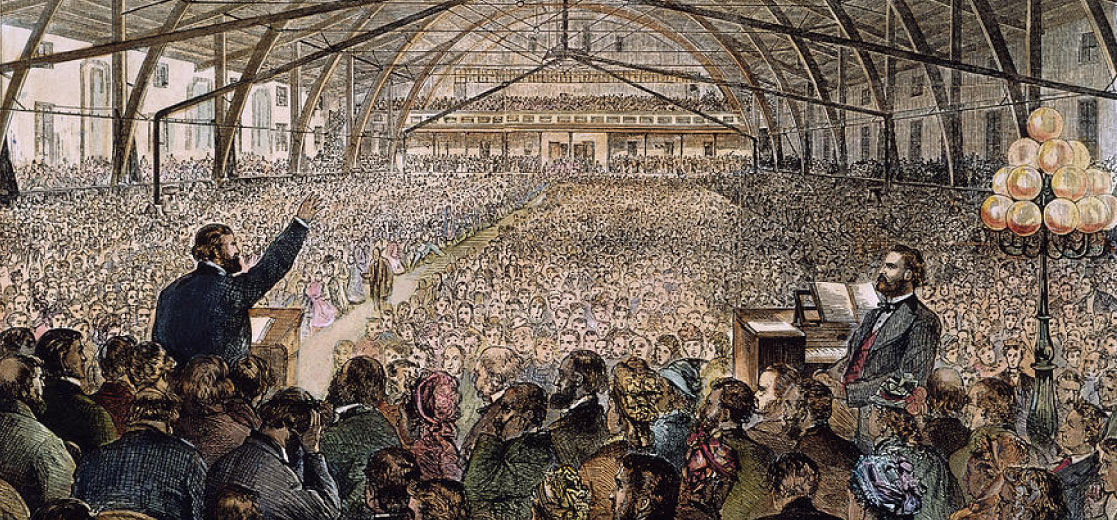

So, finally, is there hope for a new, broad, evangelical movement? Can the late, great evangelical movement of the 1950s through the 1970s be revived? Or is it gone forever? I doubt that it can be revived and I suspect it is a thing of the past. In my opinion, it would take another Billy Graham to revive it. To a very large extent it was centered around him and his many ministries. We will have to learn to live with a shattered, fragmented evangelicalism and focus our attention and energy on keeping alive the evangelical spirit, ethos, among us. It will take many different expressions and we’ll need to learn to live with them. Only when we think there is such a thing as “the evangelical movement” does diversity among evangelicals cause consternation and confusion among us. Once we’ve disabused ourselves of that notion, perhaps we can get on with the business of being evangelicals in our own, separate ways and accept others as equally evangelical without trying to make them conform to some stereotype of our own invention.

- Roger Olson