This is session one for "Empty Altars: American Saints in a Cynical Age" with Diana Butler Bass & Tripp Fuller. To join the open online Lenten class head over to www.EmptyAltars.com

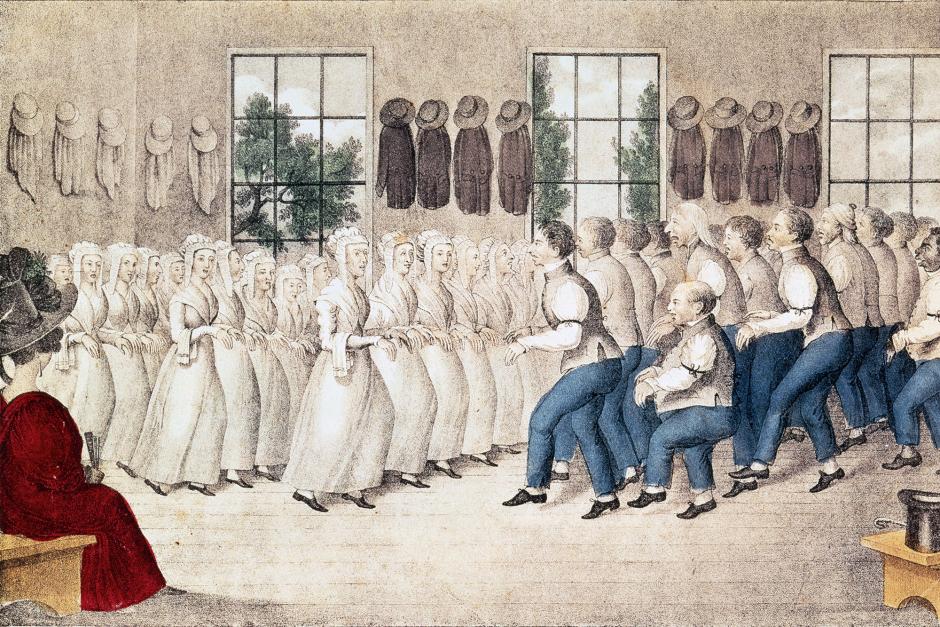

Almost 50 years ago, when portable video technology was in its infancy, Terese Kreuzer and Eugene Marlow set out to make a documentary about the United Society of Believers, commonly known as the Shakers. A celibate religious order, they had been founded by an illiterate English woman named Mother Ann Lee who, in 1774, crossed the Atlantic Ocean with a handful of followers. The Shakers lived in communes where men and women were equal in terms of authority and responsibility, owning all property in common and caring for each other and serving each other. They believed as Mother Ann did that anyone could embody the spirit of Christ who lived a pure, simple and loving life. "Put your hands to work and your hearts to God," Mother Ann taught.At one time, there were 18 active Shaker communities in the United States but by the time Kreuzer and Marlow met the Shakers, there were only two left. The one in Sabbathday Lake, Maine had eight covenanted members. The one in Canterbury, New Hampshire was even smaller. In 1992, when the last of the Canterbury sisters died, that Shaker community became a museum. But the Sabbathday Lake Shaker community is still active, though diminished in numbers, a testament to Mother Ann's belief that "No one can build a spiritual heaven without first creating a heaven on earth."

|

| Enfield Shaker Museum |

Ann Lee (February 29, 1736–September 8, 1784) was the charismatic leader of the Shakers, officially known as the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing. The illiterate daughter of a blacksmith in Manchester, England, Lee endured a difficult childhood and troubled marriage before leading a group of "shaking Quakers" to upstate New York. The Shakers became an active evangelical group with communities throughout eight states in the Northeast.

Shakers were known for their pacifism, celibacy, egalitarianism between the sexes, unique form of worship, and impressive achievements in the fields of agriculture, design, and music. By the end of the 20th century, Shakerism was essentially extinct, but its legacy continues.

Early Life

Ann Lee was born on February 29, 1736, in Toad Lane, a poor neighborhood of Manchester, England. Ann was the second of eight children born to a blacksmith, John Lee, whose income barely fed his large family. Ann was baptized in 1742 but received no schooling; as a young girl, she went to work in the textile mills to help support her family.

A sensitive young woman, Ann was able to leave the mills to find employment in the local infirmary but was nevertheless overwhelmed by the filth and poverty of Manchester. She spoke out against alcohol and developed a strong aversion to sex. Her distaste for sex was such that she actually lectured her mother against engaging in sex, even with her own husband.

The Wardley Society of Shaking Quakers

In 1758, Ann discovered the Wardley Society, a group of "shaking Quakers," a religious society led by Jane and James Wardley. The Wardleys, like the Quakers, believed in the "inner light" as the source of revelation and spiritual truth, and, like the Quakers, they started their meetings with silence, waiting for the spirit to move members to speak. Unlike the Quakers, however, the Wardleys were influenced by the Camisards (French prophets) who believed that the Second Coming of Christ was near. They also believed that, while Christ's first coming was in male form, the second coming would be in female form. "Shaking Quaker" worship quickly moved from silent meditation to dramatic confession of sins, singing in tongues, shaking, and prophesying. Ann Lee found a home with the Wardley Society, and they were equally impressed by Ann.

Marriage and Pregnancies

Four years after she joined the Wardley Society, Ann's father pressed her to marry his apprentice, Abraham Standerin. Despite Ann's reluctance to engage in sex, she became pregnant and gave birth four times. Each of her children died either in infancy or young childhood. These experiences were devastating for Ann, who saw the deaths of her children as a judgment on her for her sins and determined to remain celibate.

This period of depression and introspection lasted for nine years, during which time Ann refused to share her bed with her husband. Standerin, despite his frustrations with his wife, remained loyal to her for a period of time. A few years later, he traveled to America with her.

Jail, Visions, and a Journey

Members of the Wardley Society were often jailed for reasons ranging from blasphemy to disrupting the peace. In some cases, conflicts with the authorities were a result of the Wardley Society members disrupting other congregations and accusing married members of "whoredom."

It was in 1770, during a period of incarceration, that Ann Lee received a vision. In this vision, according to several sources, Lee saw that sex between Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden was the cause of humanity's separation from God. It was further revealed that she was the incarnation of the second coming of Christ, as foretold in Genesis and the Book of Revelation. She left jail as Mother Ann, or Ann the Word, a mystic and leader of a sect dedicated to celibacy and confession of sins.

Quite a few members of the Shaking Quakers, including some of Ann's family, accepted her vision as spiritual truth and followed her teachings as the “first spiritual Mother in Christ.” They continued to follow her when, in 1774, a vision led her to form a perfect church in America which would become the model for the Millenium. With the help of a wealthy follower, Ann and a group of followers sailed to America.

| Mother Ann Lee tombstone. Doug Coldwell / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 |

Mother Ann in America

In 1774, Mother Ann and her followers arrived in New York City where Ann's husband, Abraham, finally left her forever. A member of the group leased land in upstate New York, and, in 1776, the Shakers founded their first model farming community in a Niskayuna (now called Watervliet) New York. The community was completely celibate; women and men shared leadership and worked side by side as equals.

Even in their new surroundings, the Shakers found life difficult. As pacifists, they were unwilling to pledge their support to the American revolutionaries, and several Shakers (including Mother Ann) were jailed for being disloyal. Ann continued to preach, even through the windows of her prison cell;. Following her release she set out on a four-year missionary tour throughout the northeastern part of the new United States.

Though the new nation was undergoing a religious revival, the Shakers' unique theology and principles made it difficult to build a following. Nevertheless, Mother Ann, her brother William, and Shaker leader James Whittaker were successful in laying the groundwork for communities in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Many new Shaker converts had been members of non-mainstream groups which, like the Shakers, had been persecuted.

Death

Mother Ann's missionary tour was exhausting and involved a variety of hardships including physical assault. By the time she returned to Watervliet, she was ill; within a year both she and her brother had died. She died on September 8, 1784, at the age of 48, leaving James Whittaker, Joseph Meacham, Lucy Wright, and several other disciples to carry on the creation of multiple Shaker communities across eight states. Ann Lee was buried in the Shaker Cemetery in Watervliet, New York.

Legacy

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Testimonies_of_Ann_Lee-79847f6d9d8f4c2fab8a3a539c320942.gif) |

Title of a very first book about Ann Lee Testimonies of the Life, Character, Revelations and Doctrines of Our Ever Blessed, and the Elders with Her published by Shakers in 1816. Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons |

Ann Lee's personal story was documented by her followers in books which narrated her words, revelations, and actions (Testimonies of the Life, Revelations, and Doctrine of Our Ever Blessed Mother Ann Lee). These books, along with Mother Ann's personal influence, helped to shape the growth of the Shaker movement throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s.

Shakers were and still are well known for their egalitarian and pacifist beliefs, their celibacy, and their industry. Just as importantly, they are remembered for their significant contributions to American agriculture, design, and music.

Sources

- “About the Shakers.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-shakers/about-the-shakers.

- Ann Lee, A Woman of Great Faith, libertymagazine.org/article/ann-lee-a-woman-of-great-faith.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Ann Lee.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/biography/Ann-Lee.

- “First Shaker Settlement.” Shaker Heritage Society, home.shakerheritage.org/.

|

'Shakers near Lebanon', c1870. Members of the Mount Lebanon Shaker Community, Lebanon Springs, New York State, 'dancing' at their meeting. Artist: Currier and Ives. Print Collector / Getty Images |

Ann Lee

Ann Lee | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 February 1736 Manchester, England, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Died | 8 September 1784 (aged 48) Watervliet, New York, U.S. |

| Burial place | Watervliet Shaker Village, Colonie, New York 42.73909°N 73.81637°W |

| Other names | Ann Elizabeth Lees Ann Standerin |

| Occupation(s) | Founder of the Shakers Preacher Singer Missionary |

| Years active | 1758–1784 |

| Spouse | Abraham Standerin (separated c. 1775) |

| Children | 4 (all died in infancy) |

| Parent | John Lees |

| Relatives | William Lee (brother) Nancy Lee (niece) |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Denomination | Shaker |

| Signature | |

| |

|

| Topics |

|---|

| Notable people |

Founders

Other members |

Ann Lee (29 February 1736 – 8 September 1784), commonly known as Mother Ann Lee, was the founding leader of the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, or the Shakers.

After nearly two decades of participation in a religious movement that became the Shakers, in 1774 Ann Lee and a small group of her followers emigrated from England to New York. After several years, they gathered at Niskayuna, renting land from the Manor of Rensselaerswyck, Albany County, New York (the area now called Colonie). They worshiped by ecstatic dancing or "shaking", which resulted in them being dubbed the Shakers. Ann Lee preached to the public and led the Shaker church at a time when few women were religious leaders.[1]

Early history

Ann Lee was born in Manchester, England, and was baptized privately at Manchester Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral) on 1 June 1742,[2] at the age of 6. Her parents were members of a distinct branch of the Society of Friends and too poor to afford their children even the rudiments of education.[3] Ann Lee's father, John Lees, was a blacksmith during the day and a tailor at night. It is probable that Ann Lee's original surname was Lees, but somewhere through time it changed to Lee. Little is known about her mother other than that she was a very religious woman. As often happened in those days, the mother's name was not even recorded.[4] When Ann was young, she worked in a cotton factory, then as a cutter of hatter's fur, and later as a cook in a Manchester infirmary.

In 1758, she joined an English sect founded by Jane Wardley and her husband, preacher James Wardley; this was the precursor to the Shaker sect.[5] She believed and taught her followers that it is possible to attain perfect holiness by giving up sexual relations. Like her predecessors, the Wardleys, she taught that the shaking and trembling were caused by sin being purged from the body by the power of the Holy Spirit, purifying the worshiper.

Beginning during her youth, Ann Lee was uncomfortable with sexuality, especially her own. This repulsion towards sexual activity continued and manifested itself in her repeated attempts to avoid marriage. Eventually her father forced her to marry Abraham Stanley (or Abraham Standarin[6]). They were married on 5 January 1761 at Manchester Collegiate Church.[7] She became pregnant four times, but all of her children died during infancy. Her difficult pregnancies and the loss of four children were traumatic experiences that contributed to Ann Lee's dislike of sexual relations.[8] Lee developed radical religious convictions that advocated celibacy and the abandonment of marriage, as well as the importance of pursuing perfection in every facet of life. She differed from the Quakers, who, though they supported gender equality, did not believe in forbidding sexuality within marriage.

Rise to prominence

In England, Ann Lee rose to prominence by urging other believers to preach more publicly concerning the imminent second coming, and to attack sin more boldly and unconventionally. She spoke of visions and messages from God, claiming that she had received in a vision from God the message that celibacy and confession of sin are the only true road to salvation and the only way in which the Kingdom of God could be established on the earth. She was frequently imprisoned for breaking the Sabbath by dancing and shouting, and for blasphemy.[9]

She claimed to have had many miraculous escapes from death. She told of being examined by four clergymen of the Established Church, claiming that she spoke to them for four hours in 72 tongues.[10]

While in prison in Manchester for 14 days, she said she had a revelation that "a complete cross against the lusts of generation, added to a full and explicit confession, before witnesses, of all the sins committed under its influence, was the only possible remedy and means of salvation." After this, probably in 1770, she was chosen by the Society as "Mother in spiritual things" and called herself "Ann, the Word" and also "Mother Ann." After being released from prison a second time, witnesses say Mother Ann performed a number of miracles, including healing the sick.[11]

Lee eventually decided to leave England for America in order to escape the persecution (i.e., multiple arrests and stays in prison) she experienced in Great Britain.[9]

Move to America

In 1774 a revelation led her to take a select band to America. She was accompanied by her husband, who soon afterwards deserted her. Also following her to America were her brother, William Lee (1740–1784); Nancy Lee, her niece; James Whittaker (1751–1787), who had been brought up by Mother Ann and was probably related to her; John Hocknell (1723–1799), who provided the funds for the trip; his son, Richard; James Shepherd; and Mary Partington. Mother Ann and her converts arrived on 6 August 1774 in New York City, where they stayed for nearly five years. In 1779 Hocknell leased land at Niskayuna in the township of Watervliet, near Albany. The Shakers settled there, and a unique community life began to develop and thrive.[9]

During the American Revolution, Lee and her followers maintained a stance of neutrality. Maintaining the position that they were pacifists, Ann Lee and her followers did not side with either the British or the colonists.

Ann Lee opened her testimony to the world's people on the famous Dark Day in May 1780, when the sun disappeared and it was so dark that candles had to be lighted to see indoors at noon.[12] She soon recruited a number of followers who had joined the New Light revival at New Lebanon, New York, in 1779, including Lucy Wright.

Beginning in the spring of 1781, Mother Ann and some of her followers went on an extensive missionary journey to find converts in Massachusetts and Connecticut. They often stayed in the homes of local sympathizers, such as the Benjamin Osborn House near the New York-Massachusetts line. There were also songs attributed to her which were sung without words.[13][14]

The followers of Mother Ann came to believe that she embodied all the perfections of God in female form[15] and was revealed as the "second coming" of Christ.[16] The fact that Ann Lee was considered to be Christ's female counterpart was unique. She preached that sinfulness could be avoided not only by treating men and women equally but also by keeping them separated so as to prevent any sort of temptation leading to impure acts. Celibacy and confession of sin were essential for salvation.[15]

Ann Lee's mission throughout New England was especially successful in converting groups who were already outside the mainstream of New England Protestantism, including followers of Shadrack Ireland. To the mainstream, however, she was too radical for comfort.[17] Ann Lee herself recognized how revolutionary her ideas were when she said, "We [the Shakers] are the people who turned the world upside down."[dubious ]

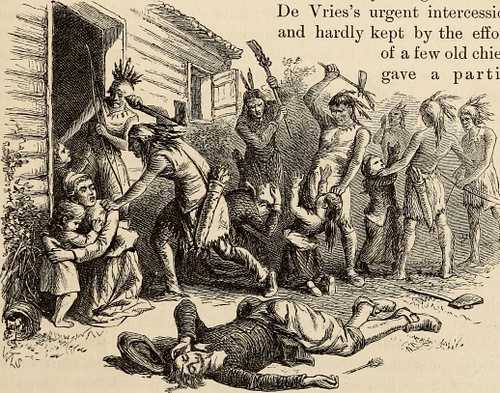

The Shakers were sometimes met by violent mobs, such as in Shirley, Massachusetts, and Ann Lee suffered violence at their hands more than once. Because of these hardships Mother Ann became quite frail; she died on 8 September 1784 at the age of 48.[9]

She died at Watervliet and is buried in the Shaker cemetery located in the Watervliet Shaker Historic District.[18]

It is claimed that Shakers in New Lebanon, New York, experienced a 10-year period of revelations in 1837 called the Era of Manifestations. It was also referred to as Mother Ann's Work.[19]

Cultural legacy

Ann Lee is memorialized in:

- Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party[20]

- the (afterword of the) novel A Maggot

- A song, "The Heart Of Ann Lee", on the 2010 album All This Longing by English folk singer-songwriter Reg Meuross

See also

- Millennial Praises

- the Public Universal Friend, contemporary leader of another new religious movement

- List of people who have claimed to be Jesus[15][16]

References

- ^ In addition to Ann Lee, only nine women preachers have been identified before 1800. Catherine A. Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 343–46.

- ^ MS 12/1, Manchester Cathedral Archive

- ^ Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- ^ Campion, Nardi (1990). Mother Anne Lee: Morning star of the shakers. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. pp. 2. ISBN 0874515270.

- ^ Campion, Nardi Reeder (1976), Ann the Word: The Life of Mother Ann Lee, Founder of the Shakers, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, ISBN 978-0-316-12767-7

- ^ "Lee, Ann (1736-1784)". Shaker Museum. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ MS 13/3, Manchester Cathedral Archive

- ^ Kern, Louis J. (1981). An Ordered Love: Sex Roles and Sexuality in Victorian Utopias: The Shakers, the Mormons, and the Oneida community. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1443-7.

- ^ a b c d Richard Francis, Ann the Word: The Story of Ann Lee, Female Messiah, Mother of the Shakers, The Woman Clothed with the Sun (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2000).

- ^ Foner, Eric; Garraty, John A., eds. (1991). "Ann Lee". American History Companion: The Reader's Companion to American History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 646. ISBN 978-0-395-51372-9.

- ^ Answers.com Mother Ann Lee (section Britannica Concise Encyclopedia: Ann Lee)

- ^ Francis, Ann the Word, 130–31

- ^ "Shaker Music". PineTree Productions.

- ^ Roger L. Hall (1999). A guide to Shaker music: with music supplement. Pinetree.

- ^ a b c Rufus Bishop and Seth Youngs Wells, comps., Testimonies of the Life, Character, Revelations and Doctrines of our Ever Blessed Mother Ann Lee (Hancock, Mass.: J. Talcott and J. Deming, Junrs., 1816); Seth Youngs Wells, comp., Testimonies Concerning the Character and Ministry of Mother Ann Lee (Albany, N.Y.: Packard and Van Benthuysen, 1827).

- ^ a b Frederick William Evans. Shakers: Compendium of the Origin, History, Principles, Rules and Regulations, Government, and Doctrines of the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing : with Biographies of Ann Lee, William Lee, Jas. Whittaker, J. Hocknell, J. Meacham, and Lucy Wright. Appleton; 1859. p. 26.

- ^ Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845, 343–46.

- ^ Landmarks of American women's history, Chapter: Watervliet Shaker Historic District, Page Putnam Miller, Oxford University Press US, 2003, pp. 36 ff.

- ^ Aune, Michael Bjerknes; DeMarinis, Valerie M. (1996). Religious and Social Ritual: Interdisciplinary Explorations. SUNY Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-7914-2825-7.

- ^ "Ann Lee". The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

Further reading

- Campion, Nardi Reeder. Mother Ann Lee: Morning Star of the Shakers Publisher: UPNE. 1990. ISBN 0874515270

- Francis, Richard (2000). Ann the Word : the story of Ann Lee, female messiah, mother of the Shakers, the woman clothed with the sun. New York : Arcade Pub. : Distributed by Time Warner ISBN 1559705620

- Hall, Roger Lee. Invitation to Zion: A Shaker Music Guide. Publisher: PineTree Press, 2017.

- Stein, Stephen J. The Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers (Yale University Press, 1992). ISBN 0300059337

- Hager, Jacob Henry (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Rigg, James McMullen (1892). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 32.

- Claus Bernet (2002). "Ann Lee". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 20. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 899–911. ISBN 3-88309-091-3.