Another paradigm with remarkable overlap with

Emergentism, despite coming from a very different starting place, is the

analytical psychology pioneered by Carl Jung in the early to mid-20th century.

The focus of Jungian psychology, and the aim of its associated therapies, is essentially making the unconscious conscious—that is, bringing to the full light of conscious awareness what had formerly been obscured, neglected, or unknown about the psyche. According to Jung, that is the universal aim of all conscious beings.

The very first sentence of Jung’s autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections echoes this universal theme. “My life,” recounts Jung,

is a story of the self-realization of the unconscious. Everything in the unconscious seeks outward manifestation, and the personality too desires to evolve out of its unconscious conditions and to experience itself as a whole.

The individual is but a participant in a much larger collective process of the growth and deepening of consciousness per se.

The therapeutic aspects of this process are familiar enough, as when one sees a therapist who helps uncover a traumatic experience that had been repressed (i.e., pushed into unconsciousness), allowing for healing and wholeness.

For Jung, this method only expresses in miniature what is happening at a much grander, collective level. The increase in consciousness we experience as individuals mirrors the historical emergence of consciousness in general as it evolved and deepened through the life of humanity.

The importance of the emergence of human consciousness for the universe as a whole eventually crystallized for Jung as the emerging myth of human history. In a flash of realization, he saw how this human endeavor was the basis for a whole new sense of cosmic meaning. For, only with consciousness does the Universe truly come into being. “By virtue of his reflective faculties,” writes Jung,

man is raised out of the animal world, and by his mind he demonstrates that nature has put a high premium precisely upon the development of consciousness. Through consciousness he takes possession of nature by recognizing the existence of the world and thus, as it were, confirming the Creator. The world becomes the phenomenal world, for without conscious reflection it would not be.

Without a subjective knower, the objective Universe would remain unknown, unconscious of itself—as, indeed, it was for billions of years. But with the rise of conscious observers, the Universe awakens. Creation is confirmed. God becomes conscious of himself—through the mind—and the whole tumultuous epic of evolution begins to clarify:

If the Creator were conscious of Himself, He would not need conscious creatures; nor is it probable that the extremely indirect methods of creation, which squander millions of years upon the development of countless species and creatures, are the outcome of purposeful intention. Natural history tells us of a haphazard and casual transformation of species over hundreds of millions of years of devouring and being devoured. The biological and political history of man is an elaborate repetition of the same thing. But the history of the mind offers a different picture. Here the miracle of reflecting consciousness intervenes—the second cosmogony. The importance of consciousness is so great that one cannot help suspecting the element of meaning to be concealed somewhere within all the monstrous, apparently senseless biological turmoil, and that the road to its manifestation was ultimately found on the level of warm-blooded vertebrates possessed of a differentiated brain—found as if by chance, unintended and unforeseen, and yet somehow sensed, felt and groped for out of some dark urge.

In this way, the unconscious God is finally rendered conscious of himself—by means of humanity. The eons-long development of human consciousness, gradually groped towards through a nearly blind process of biological evolution, was the means by which God has become Self-aware. “Man,” says Jung, “is the mirror which God holds up before him, or the sense organ with which he apprehends his being.” Or, as he puts it elsewhere: “Human consciousness is the only seeing eye of the Deity.”

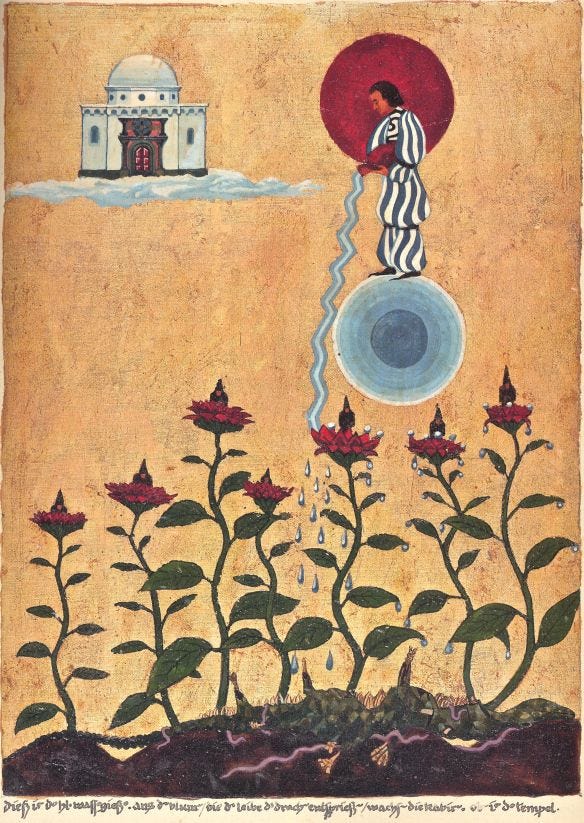

|

| An illustration from Jung’s Red Book |

For Jung, this psychological realization returned the genuinely religious sensibility to modern man, whom reductionistic materialism had otherwise left mythologically adrift in a meaningless, indifferent cosmos, without aim or purpose.

Appreciating humanity’s role once more in a divine drama returned it a position of significance in the grand scheme of reality—a causal role that had been lost with the decline of traditional religion. Now, man could once more serve his God—not through burnt sacrifices and offerings, but through the very expansion of his consciousness:

That is the meaning of divine service, of the service which man can render to God, that light may emerge from the darkness, that the Creator may become conscious of His creation, and man conscious of himself. That is the goal, or one goal, which fits man meaningfully into the scheme of creation, and at the same time confers meaning upon it…

|

| An illustration from Jung’s Red Book |

The great Jungian analyst and philosopher Edward Edinger saw in Jung’s vision nothing less than “the new myth” for our time. In his book The Creation of Consciousness: Jung’s Myth for Modern Man, Edinger summarizes the new grand narrative in this way:

The new myth postulates that the created universe and its most exquisite flower, man, make up a vast enterprise for the creation of consciousness; that each individual is a unique experiment in that process; and that the sum total of consciousness created by each individual in his lifetime is deposited as a permanent addition in the collective treasury of the archetypal psyche.

That treasury is the evolving God-image itself, which grows in resolution and clarity as humanity awakens to greater understanding of its Self, rendering more of the unconscious conscious:

On the basis of our emerging knowledge of the unconscious the traditional image of God has been enlarged. Traditionally God has been pictured as all-powerful and all-knowing. Divine Providence was seen as guiding all things according to the inscrutable but benevolent divine purpose. The extent of divine awareness did not receive much attention. The new myth enlarges the God-image by introducing explicitly the additional feature of the unconsciousness of God. His omnipotence, omniscience and divine purpose are not always known to Him. He needs man's capacity to know Him in order to know Himself.

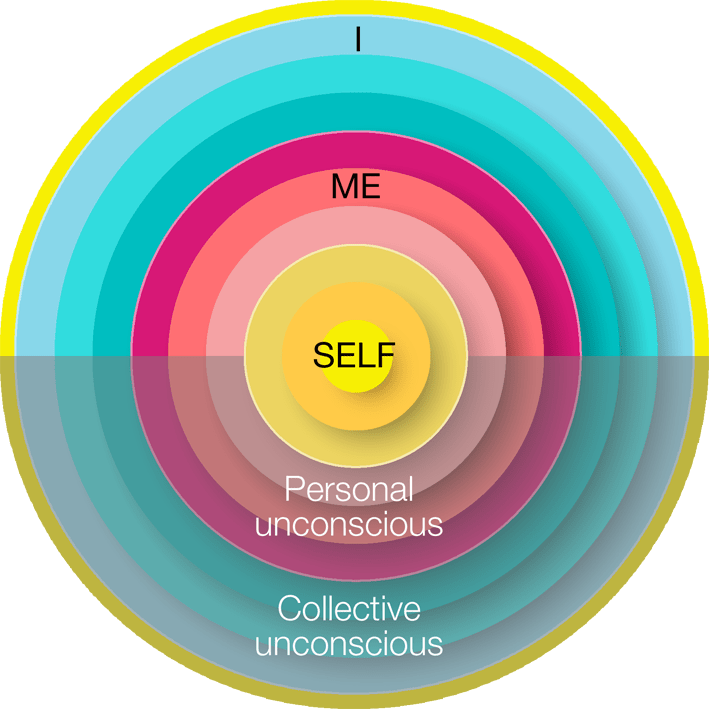

In Jungian psychology, the nature of consciousness itself is probed and made conscious in relationship to certain

archetypal images, such as one finds continually recurring in the world’s mythologies and religious traditions.

These archetypes provide symbolic representations of unconscious dynamics which, through their tangible manifestation in Culture, become objects of consciousness. That objective manifestation of unconscious content into the light of consciousness allows it to be engaged by the subject, who can then process, accept, and ultimately use it as the basis of further growth. In this way, the “symbolic imaginary” of human Culture continually develops and expands as the (collective) psyche grows in self-understanding—a psychological description of the process of cultural evolution we described earlier.

According to Jung, God is one such archetype—the greatest one, in fact, for God is an archetype of the Self (see pp. 127-128). The evolution of the God-image thus evolves with the development of the Self. In this way, the development of the human psyche, the Self, is the means by which God develops. “Mankind is now caught up in the process of divine transformation,” says Edinger.

God has fallen into man and man has become a participant in the divine drama. This fact remained on the symbolic, projected level as long as the process was confined to one man (Christ) who was worshipped as divine. But now, with the psychological understanding of this imagery, the experience becomes available potentially to all individuals.

In this way, Jung concludes (just as Hegel does) that the “picture-thinking” of the Christian myth is but an early developmental stage that leads towards the universal awakening to God consciousness in the life of every individual subject.

|

| Icon of the Transfiguration of Christ |

In Christianity, we find the realization of God consciousness projected as a story, something “out there” that happened long ago to a particular divine human. With the development of consciousness, though, we can now see that this mythic image was actually speaking to something that happens internally. We learn to withdraw the projection, taking in what had been externalized, and thereby find God consciousness as a reality to be experienced by all conscious beings. This mystical union of subject and object, the “conjunction of opposites” as Jung considered it, is the ultimate aim of the evolution of consciousness, where the Self is finally identified as God.

But, like the Hegelians, the Jungians appreciate that this Self-realization caps a developmental progression that has been unfolding over millennia, throughout the various epochs of human cultural evolution. Culture is the locus of humanity’s increasing self-consciousness, and thus the locus of the divine drama of God’s coming to full Self-consciousness.

In the stages of culture, we can see the evolution of consciousness playing out, and plot the progression of consciousness’s advance by looking at the symbols that have been emerging from the collective unconscious.

In his great work The Origins and History of Consciousness, Jungian psychologist and philosopher Erich Neumann provides a survey of this evolution. Whereas Hegel could only philosophically speculate on the movement Spirit takes through an idealized (if often highly arbitrary) logic, Neumann can bring to bear the insights of analytical psychology, with all its empirical grounding in individual psychotherapeutic analysis.

Because the unconscious is not only individual but collective, evidence from personal psychological development shines a light on the evolution of the collective archetypal Self, which is to say, God. The evolution of God thus mirrors the evolution of the psyche, and vice versa. “In the course of its ontogenetic development,” writes Neumann,

the individual ego consciousness has to pass through the same archetypal stages which determined the evolution of consciousness in the life of humanity. The individual has in his own life to follow the road that humanity has trod before him, leaving traces of its journey in the archetypal sequence of the mythological images…

Or, as he puts it elsewhere: “The evolution of consciousness by stages is as much a collective human phenomenon as a particular individual phenomenon. Ontogenetic development may therefore be regarded as a modified recapitulation of phylogenetic development.”

Analytic psychology is further enriched, compared to Hegelian phenomenology, by its appreciation of archetypal images that arise in the evolution of consciousness. Whereas Hegel spoke of “shapes of consciousness” figuratively, Jungian analysis can actually bring genuine symbolic forms to bear in its tracking of psychological development.

Mythic imagery is the specific imaginal content that evolves through different stages of consciousness. “Consciousness thus acquires images (Bilder) and education (Bildung), widens its horizon, and charges itself with contents which constellate a new psychic potential.”

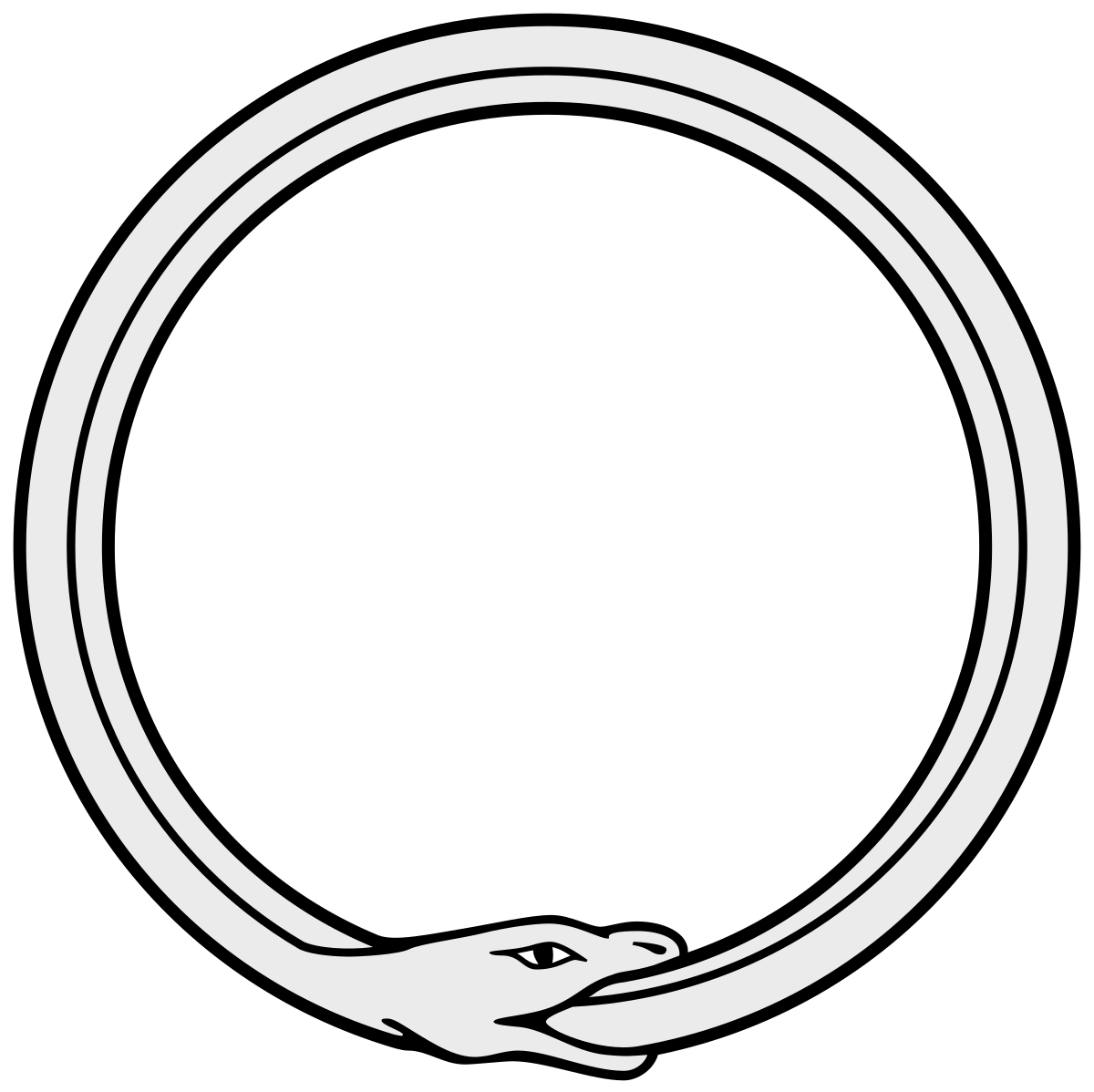

So Neumann can not only describe the emergence of 0D consciousness, but also link it to the specific mythic image with which it historically and psychologically correlates—in this case, the Ouroboros.

This is the mythic Dragon of Chaos, the primordial matrix of the undifferentiated matter, and thus the mater (Mother) of all being—the Unconscious per se. At this level, the individual remains psychologically (con)fused with their environment. As Neumann puts it: “Nothing is himself; everything is world.” The Ouroboros is a boundless symbol of infinity—just as a geometric point represents an infinitesimal. There is nothing outside of it. Its domain is the vast sea, the sprawling depths, the bottomless abyss—the dark unconscious.

The Ouroboros is the archetypal symbol of 0D consciousness, then, and the Animistic worldview of early conscious humans (cf.

p. 110). Its psychic confusion stands as a chaotic lack of distinction and organization relative to the increasingly complex Self that will emerge from it. The Dragon is thus a symbol of chaos and entropy, from which Creation arises through successive stages of complexification (i.e., differentiation and integration). (For instance, from the “formless and void” waters in Genesis, the Creator initiates a series of separations that serve to organize the world; Tiamat, the Sumerian mother Dragon of Chaos, is divided in order to create the world, etc. Cf.

my monograph on this mythic trope and its application in the New Testament.)

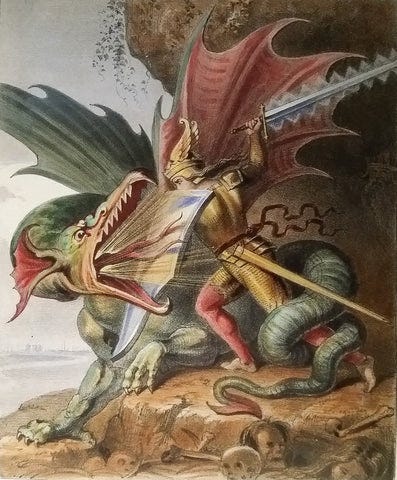

The transition to 1D consciousness marks the differentiation of a strong individual ego, and thus a separation from the Ouroboric matrix. The archetype of this level of consciousness is thus not the Dragon, but the Dragon Slayer—he who slays and divides the Dragon. The Hero is born.

Culturally speaking, the level of metameme or justification system becomes that of Imperial culture, with all its glorification of the hero and the valorization of the independent, egoic strength and power of the individual (cf. pp. 149-151). In terms of the God-image, we find the concretization from diffuse mana to the anthropomorphic pantheon of deities. So Neumann notes that “there is…a connection between the hero as bearer of the ego, with its power to discipline the will and mold the personality, and the formative phase in which the gods are crystallized out from a mass of impersonal forces…” just as we noted earlier.

The Hero Myth, though, which is to say the Fight with the Dragon myth, is really the archetype of all differentiation processes. Since psychological development and individuation proceed by a movement of differentiation and integration—of the subject becoming an object to itself at a higher level of awareness, as psychologist Robert Kegan puts it—the archetype recurs at every stage of development. Neumann observes:

The dragon fight is correlated psychologically with different phases in the ontogenetic development of consciousness. The conditions of the fight, its aim and also the period in which it takes place, vary. It occurs during the childhood phase, during puberty, and at the change of consciousness in the second half of life, wherever in fact a rebirth or a reorientation of consciousness is indicated.

The nature of the “Dragon” thus shifts with each developmental movement. For the 2D consciousness embracing a moralistic religious worldview, the Dragon is the Devil (itself a symbol of 1D egoic pride); whereas for the 3D consciousness embracing an individualistic modern worldview, the Dragon is the stifling constriction of the old traditional order (which is to say, the 2D world) (e.g., the Enlightenment thinker Voltaire’s injunction to “Écrasez l’infâme!” or “Crush the infamy! of the Roman Catholic Church). The Hero is thus always overcoming older, outmoded levels of consciousness on the way to greater self-knowledge. The Dragon becomes whatever embedded matrix must be transcended on the psyche’s progression into uncharted territory.

This process of differentiation (recognizing the distinction of subject from objective background) and then integration (recognizing that object as existing within the subject) is the developmental psychological movement per se. As a process, it can be said to culminate only once the subject has ceased confusing herself with the world and has withdrawn all projections into herself—even God. For, “so long as God is exteriorized,” says Neumann,

he acts as the “real God outside,” though a later consciousness may then diagnose him as a projection of the God-image which dwells in the psyche. The formation and development of human personality largely consists in “taking in”—introjecting—these exteriorized contents.

The last object is taken into the subject, and the Self is fully understood. The psyche is all. Neumann writes: “It is necessary for the structure of personality that contents originally taking the form of transpersonal deities should finally come to be experienced as contents of the human psyche.” This is the aim towards which psychological development unfolds—one it is continually reaching towards as consciousness evolves, ever new Dragons are slain, and the Hero becomes more and more sure of himself.

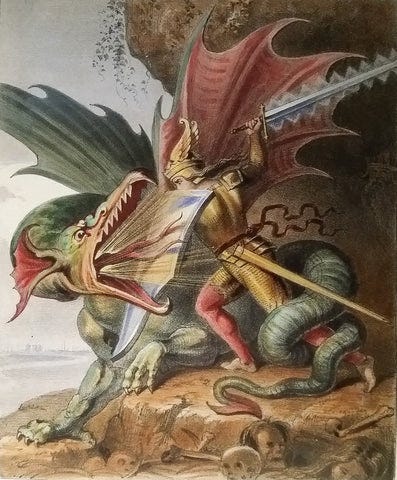

|

From Adyahanzi’s ‘Songs of the Self’: The Imperial myth of the

Sun God slaying the Ouroboros in which he lay swallowed up |

As Edinger expressed it, the knowing of the world develops into a knowing of the self, which then evolves into a knowing with the Self:

[W]e begin our psychic existence in the unconscious state of known object and only laboriously, with the growth of the ego, achieve the relatively tranquil status of knowing subject. Then, if development is to proceed, the relative freedom we have won must be relinquished as the ego becomes aware that it is the object of a transpersonal subject, namely the Self. After both of these experiences the way is open for the reconciling third, which I take to be the full meaning of “knowing with.”

According to Edinger, “The experience of knowing with can be understood to mean the ability to participate in a knowing process simultaneously as subject and object, the knower and the known.” Such, as we saw, is the essence of the mystical experience, where knower and known come together and God consciousness manifests.

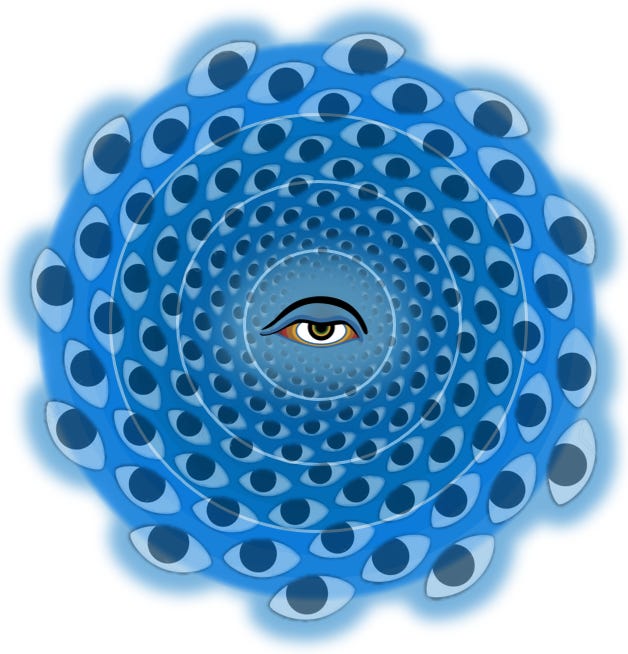

In such a state, the self perceives itself as an object of the Self, as well as a subject relating to the Self. So, Edinger says, “the full experience of being the known object of an ‘other’ knowing subject is…experienced as an encounter with the inner God-image, the Self. The archetypal image that carries the clearest symbolic expression of the ego’s experience of being the known object is the image of the Eye of God.”

Jungian analysis would thus affirm our representation of God consciousness in terms of the Kaleidoscopic Eye (p. 137) The awakened Eye is the same for both Seer and Seen. Or, as Meister Eckhart put it: “The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me; my eye and God's eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, one love.”

In this way, according to Edinger, each demands the other: “because the Self has been seen by the ego, the Self’s consciousness has been promoted. In this way, God—or the Self—needs man.” The Self sees the ego, and exalts it to its transpersonal reality, while the ego sees the Self and allows it to incarnate in concrete, actualized reality.