I wish to present Brendan Graham Dempsey's discourse on designing new civilizations of ecology, religion, science, and cultural behaviours, as aligned with my own these past many years. And though I have been steadily applying AN Whitehead's Process Philosophy to all human disciplines, I sense Brendan's Emergentism group is eclectically picking-and-choosing across a similar space which I have described in the past as the additive parts to the whole of process thought as an integral philosophy to all previous thoughts and constructs. Hence, I deem Process Philosophy as a broadly holistic construct in which all other constructs fit within such as process theology, process religion, process science, process evolution, process ecology, and so... including the area of emergentism. So, let's get to it and see where emergentism goes as an eclectic practice drawing across a variety of thought systems in reviving and resurrecting global, regional and local cultures for the 21st Century.

R.E. Slater

June 1, 2024

Emergentism | Chapter 1:

From Religion to Reduction

SEP 13, 2022

Parts and Wholes

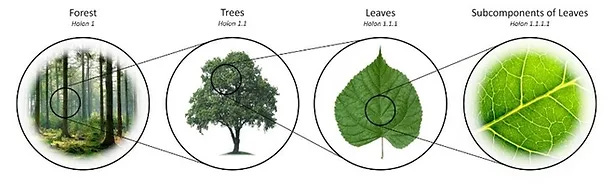

Emergentism, as its name suggests, is about emergence. But what is emerging, and out of what does it emerge? Well, broadly speaking, we can say that new wholes emerge out of lower-level parts.

All wholes are made up of parts, which have their own particular qualities. However, when parts come together to create a distinct new entity with its own unique and irreducible qualities, then you get a whole. It’s pretty much that simple.

Think of an orchestra as an analogy. It has a string section and a brass section, the woodwinds and the percussion. Each section has its own unique characteristics, its own timbre, range, and tone. But when you bring them all together, something special happens. They create something unique. When combined, all work as one—literally, “in concert”—all parts harmonizing together into a new distinctive whole that none could accomplish on its own: AKA, the symphony. Sounds pretty, doesn’t it?

Of course, once you start thinking in these terms, you recognize that this part-whole pattern goes even deeper. For instance, the string section of an orchestra is, in turn, made up of its own parts: violins and violas, cellos and basses. Each of these instruments likewise has its own unique characteristics at an even smaller scale. When brought together, they form a second-order whole: the string section.

So a whole orchestra is made up of whole sections, which are in turn made up of whole instrument groups, which are of course made up of whole instrumentalists—and so on.

Parts, then, are just lower-level wholes themselves. Parts form wholes, and those wholes serve as parts in even greater wholes. Theoretically, the process is unlimited.

Once you have this basic idea in your head, you can start to look at everything in the world this way. Anything you consider will be a whole made up of smaller parts, which in turn may be considered in terms of its parts, and so on.

Okay, you say; that’s all well and good—but so what? Why does this matter?

Surprisingly, it actually matters quite a lot. For one thing, it matters for what matters. Bold as the claim may be, I think we can actually trace the origins of the meaning crisis to the way we think about parts and wholes.

The assumptions we make about these truly fundamental concepts can have profound implications for our worldview. And a worldview with a broken sense of how parts relate to wholes can break our relationship to the whole world. And isn’t that precisely what has happened?

Consider, for instance, that meaning itself is a whole-part relationship. For something to have meaning, it must be a means—that is, it must exist for something else, as a means to something else. It must have a causal significance, we would say, in something “bigger” than itself.

In the context of the orchestra, each musical part has a meaning that’s intelligible only at the level of the whole. Any violist will know (especially since they tend to get the harmonies and not the melodies) how meaningful their contribution is, not at the level of their part alone (which is fundamentally relative and incomplete), but in concert with the rest of the orchestra.

Indeed, you could say, the violist’s part in a Beethoven symphony, for example, is virtually meaningless outside the context of the rest of the orchestral score. Simply put, to have meaning is to be an important part in a larger whole.

If, then, our sense of the relationship between parts and wholes becomes corrupted, we are at risk of losing our very sense of meaning itself—just as, in fact, we have done. We have become parts without a whole, at the same time that we cannot even claim to be whole ourselves.

But how did that happen? And is there anything that suggests we might be able to find our way out of this fractured way of thinking?

As it turns out, the answer to both of these questions is the same: the development of science…

Holistic Religious Traditionalism

All light casts a shadow, it is said. Progress creates its own problems. This, of course, doesn’t mean we should shun the light and resist any kind of advancement—only that we should always be seeking to cast new light on the shadow and keep progressing beyond today’s new problems.

We need to remain vigilant to correct for the new errors that our very attempts at error-correction may introduce along the way. In fact, that itself is science, and the continual refinement of knowledge that keeps refining our worldview.

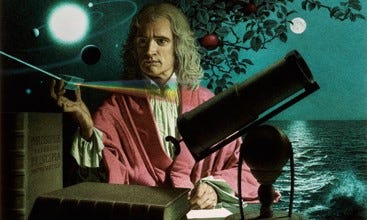

When the scientific method was first developed in earnest in the 1600s, and geniuses like Galileo and Newton began to reveal the hidden patterns of reality with astonishing precision and predictive power, the world entered a new phase. Modernity as we know it had begun.

The break from the pre-modern world was profound and irrevocable. The conclusions that scientists were drawing from their data were of a radically different sort than those espoused by the prevailing dogmas of the day—mythic and religious conceptions of the world rooted in centuries of tradition.

The traditional religious worldview had, by this time, its own highly developed ideas, complete with its own metaphysics (fundamental philosophical presumptions about how reality works) and cosmic story.

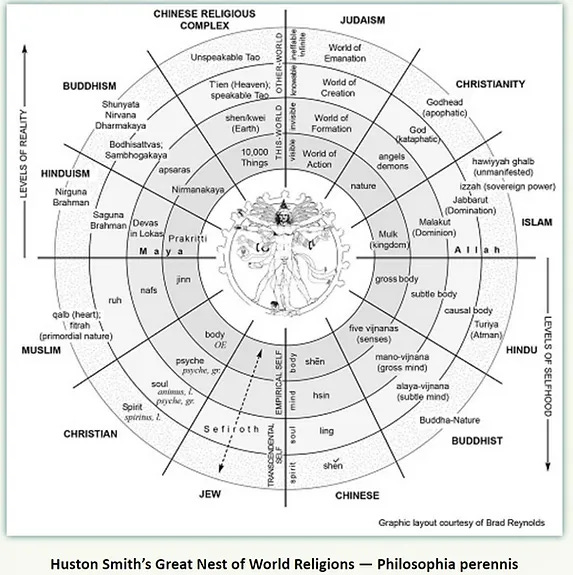

According to the metaphysical framework of the traditional worldview, everything was significant, everything hung together, everything was connected. The universe was one great whole made up of different levels or grades of being.

This “Ladder of Nature” or “Great Chain of Being” (as it came to be formulated) connected everything in Creation, from God at the top, to angels in heaven; humans, animals, plants, and minerals on Earth; all the way down to demons and the Devil in hell.

Nor was this idea unique to the West. The East had its own version of the Great Chain, stretching from Ultimate Reality (Brahman, Nirvana) down through the heavenly devas in their divine abodes, to the earthly realm, and finally to the hell realms.

In fact, this conception was so cross-culturally universal, it has been called the basis of the “perennial philosophy” of the traditional worldview.

Set within this metaphysical framework, like the performance of play upon a stage, was a traditional cosmic story. In Christian Europe just before the scientific revolution began, this story was one of a divine creation, a sinful fall from grace, a divine redemption, and a coming judgment.

In the beginning, God created the world, including humans and all the animals, to exist in an originally perfect state. But humans were quickly tempted by the Devil to transgress against God’s will—the punishment for which was a mortal life of suffering, ending in eternity in hell. God, however, sent down his Son from heaven to redeem the fallen world and thereby allow humanity entrance into heaven. His return is imminent, whereat all of the world will face judgment, and either be thrown into hellish torment or risen up into heavenly bliss. In the interim, believers have the responsibility to save as much of the world as possible by spreading the good news of salvation to unbelievers, and so ready the Earth for the coming judgment.

In this way, humanity was believed to play a part in the whole cosmic narrative. All were actors—and important ones—in the divine drama. An individual life by itself might seem full of confusion and suffering; but in the wider context of the whole divine plan, it had meaning. Humanity was part of something bigger, a higher purpose under a higher power.

As those who attended regular church services (which is to say, pretty much everybody) would have heard read from the Bible at the pulpit then:

Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body… Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it. …If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it.(1 Corinthians 12:12, 27, 26)

Under God, the inherent connectedness of everything rendered everything potentially significant and full of meaning. The stars above could be read for what events they foretold, and what impact they had on one’s life. The ancient dictum “as above, so below” demanded that the earthly and heavenly, the whole and the individual, were intimately related—even models or types of the other. And similarities of any kind between two things—shape or color, for instance—could be interpreted as meaningful ties with real causal significance.

Actually, to say that the pre-modern, traditional worldview allowed people to feel like meaningful parts of the whole might be putting the cart before the horse. To even recognize a part-whole relationship first requires a differentiation process, whereby the whole can be differentiated into its distinct parts. If this isn’t done, or done only minimally, then part and whole remain (con)fused, undifferentiated, indistinct.

Surprising as it may sound, the categories of “subjective” and “objective” only come to full prominence with modernity, meaning that people tended to blur these categories much more in the past than we do today. In the modern world, people separate their experience of reality from reality itself. In the pre-modern world, this was not done in the same way or to the same degree.

With considerably less distinction made, people’s experience felt more whole. They experienced reality as more holistically intuitive, since there was no profound divide between inner and outer worlds. The world was one. As within, so without.

Appreciating this allows us to understand the Great Chain itself much better, since it presents a cosmic whole arranged by levels of value.

God, the best thing imaginable, is on the top; the Devil, the worst thing, on the bottom. Value was inherent to the world, an aspect of things themselves, as they really are—and not just something we subjectively overlay on top of a value-neutral objective world. Meaning, then, was something real—as real as rocks and trees and tables. And the cosmos itself was ranked by an “ontological normativity”—a metaphysical hierarchy where value and being were fused.

The upshot of all this was that, whatever else plagued it, and whatever other pathologies it may have been prone to, the traditional religious worldview was certainly not threatened by any meaning crisis. Meaning was everywhere, all around. Everything was meaningful, charged with significance, part of an intrinsically value-laden cosmos and a divine narrative that had a role for every soul to play.

But all of that would change. For, with the advent of early modern science, an entirely new conception of the part and the whole comes to the fore—and, with it, an entirely new worldview.

The Rise of Modern Science

The world, we all know, is immensely complex. The word “complex” comes from Latin and means “woven together.” And that is indeed an apt metaphor, since all you have to do is look around you to see the countless varied phenomena endlessly interacting, intermingling, and interrelating in infinite combinations.

A worm eats the decaying leaf of a tree, helping both fertilize and aerate the soil the tree itself grows in, allowing more water to be soaked up from the ground, which a storm, whose lightning put nitrogen in the soil for the tree, dropped after being pushed along by weather currents influenced by the forest (including the tree) on which it fell…

The world is an infinitely rich tapestry of different threads all interweaving in a dizzying array of combinatorically explosive ways!

Beautiful as this tapestry is, though, its endlessly interrelated lines make the whole impossible to understand with any clarity or certainty. To the inquiring mind eager for greater knowledge of reality, the intricate braid starts to feel like a twisted knot. Follow one thread, and immediately you become lost in a tangle of confusion and uncertainty. Where one line of causation ends and another begins is impossible to tell in the interlaced lattice of life’s complexity.

What can we ever know about anything, when everything is bound up with everything else?

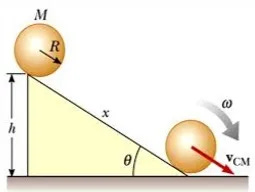

The genius of the early modern scientists was to slowly, patiently, methodically, unravel from the snarled mess one single strand for study. Then, and only then, could they measure, assess, and know, with certainty, the properties of something, where before there was only ignorance. With this, they could then begin to see how each strand relates to the others and piece together how reality behaves as a whole—since what is a whole but the sum of its parts?

Think of it this way: If you’re making a loaf of bread from scratch, but keep getting vastly different results, what do you do? Well, you could change a few different things each new loaf you make—but if one comes out perfect, how will you know just what you did right in order to repeat it? Was it the longer rise time, the higher temperature, or the extra yeast that did the trick? You’ll never know, unless you try adjusting each one individually. Only once you’ve isolated each variable will you be able to write the official recipe—and get perfect loaves every time.

This is how we’ve come to use rationality to analyze the world. The word “analyze” means, literally, “to break apart.” By breaking the world into its parts and assessing each one in isolation, the early modern scientists hoped to gain an understanding of how the whole loaf of reality works.

And, in countless crucial ways, they did! The astonishing triumph of modern science (as well as its limiting weakness, as we’ll see) lay in this: its isolation of the part from the whole.

When Galileo set out to understand the fundamental principles of motion, he didn’t go outside and look at the trees swaying in the wind or the water rushing down a river. (There are, we would now say, far too many variables to account for in such a context.) Instead, he went inside, shut out the noisiness of nature, and devised a controlled experiment—one that intentionally weeded out any possible interference with the one variable he wished to isolate and study. He reduced the vast number of potential interacting phenomena to a single, isolated instance more amenable to scrutiny—rendering the complex simple. Removing the part from the relentless interference of its contextual whole, he was able to discover a definite and repeatable pattern of behavior, and thereby establish universal principles. The simpler part could then be used to explain the much more complicated whole. In this way, complex phenomena could be seen as ultimately reducible to their simpler parts.

This was the methodological insight that broke the world wide open for infinitely greater understanding and technological progress, yielding a torrent of entire fields of knowledge and the practical industries based on them.

It was also, in its way, what broke the world.

This methodical approach—which has come to be called reductionism—became the essence of the early scientific enterprise. Once the first scientists began their analytical studies, breaking the world into its parts to explain how things work, they set off a domino cascade of dissection: the isolation of smaller parts led to the realization that those parts were themselves actually wholes made of still smaller parts—and so on and so forth.

A few decades after Galileo, Robert Hooke peered through his microscope and discovered that a plant organism was made of smaller parts, which he called “cells.” In 1811, Amedeo Avogadro wrote of even smaller parts, which he called “molecules,” following only shortly after John Dalton’s articulation of the modern theory of atoms in 1803. In 1897, with the discovery of the electron, J. J. Thomson declared that even the “uncuttable” atom had parts—a realization that ushered in a rash of subatomic particle discoveries in the early and mid- 20th century, crowned as recently as 2020 with the discovery of the famed Higgs boson.

With each lower level of discovery, the explanation for how the world works was reduced a step further. Each deeper part was considered more fundamental than the last, as the behavior of life might be explained by cells, cells by molecules, molecules by atoms, and atoms by subatomic particles.

As this reductionist approach took hold, it was increasingly believed that everything could be explained in this way. Even the most seemingly complex phenomena could be understood, in the last analysis, as the composite machines that they actually are—including living organisms and, yes, human beings, too.

So, as early as 1651, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes could confidently proclaim:

For seeing life is but a motion of limbs, the beginning whereof is in some principal part within; why may we not say, that all ‘automata’ (engines that move themselves by springs and wheels as doth a watch) have an artificial life? For what is the ‘heart’ but a ‘spring’; and the ‘nerves’ but so many ‘strings’; and the ‘joints’ but so many ‘wheels,’ giving motion to the whole body, such as was intended by the artificer?

If the world is ultimately explicable in terms of its components—that is, if the whole is ultimately no more than the sum of its parts—then life itself, like everything else, is ultimately no more than mechanical particles in motion.

In fact, many recognized, if this is so, and if the complete course of bodies in space can be determined by of laws of motion devised by Galileo and Newton, then everything is already pre-determined! Theoretically, knowing the position and velocity of all the particles in the universe would allow you to deduce its entire history and future, since the universe is governed by the same physical principles as billiard balls colliding on a pool table.

The famous scientist Pierre Simon Laplace declared as much in 1795, writing:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes. (“A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities”)

Determinism, which followed ineluctably from the logic of reductionism, meant that human beings, despite our experience, actually had no free will at all, and that our sense of being autonomous agents was actually, at base, just an illusion.

True causal power only existed at the level of the smallest part, which science revealed to be mechanical and deterministic. Everything higher up, any higher whole, was ultimately driven by that deeper logic—because surely wholes are no more than the sum of their parts.

Reductionism and the Meaning Crisis

As reductionism became more and more engrained in the scientific enterprise, and the mechanized world it produced became everywhere more impressive and ubiquitous, the pre-modern world and its religious worldview faded increasingly from sight.

The meaning-rich world of inherent value was replaced by a mechanistic, value-neutral objectivity (described by forces, not feelings). Value could not be shown to be something subject to force and motion, and so must not be fundamentally real. Values exist only in our minds, then—such that there must exist a sharp divide between the subjective and the objective. Mixing them together is the source of endless confusion, since, ultimately, only the objective world is real.

Likewise, with the explanatory power that particles and forces provided, there was no longer any need for supernatural explanations of phenomena. (As Laplace answered Napoleon when asked about the absence of God from his work: “Sire, I had no need of that hypothesis.”) Nor did mere associations or “correspondences” serve a use any longer, nor the supposed influence of the stars—which Newton had shown to be governed by the same laws as prevail on Earth. Everything could—or would—be explained by simple material part-icles in motion: a metaphysical framework known as materialism.

Thus, with the triumph of reductionism, the entire religious edifice of tradition cracked, its metaphysical Great Chain and cosmic story rapidly eroding. In its place was modernity’s new worldview—with its own metaphysics and unnerving new narrative.

This metaphysical framework was valueless. The hierarchy of reality was not organized by good and evil, only size—and the smallest parts were the most important. There was no personal God, only deterministic laws that govern the universe—and these were as indifferent to humans’ existential lot as any machine. Whatever could not be described in terms of fundamental particles in motion was either a fiction or an illusion.

The cosmic story of this worldview was, as a consequence, radically different from that of traditional religion. Having stripped a benevolent God of any causal power, there was no providential “creation” per se; the universe just was (and presumably always was; or, if it did have a beginning, arose from chance).

There was no divine drama or omniscient Plan. Human beings, and all life, were essentially just complicated machines, governed not by their agency but by their constituent parts following deterministic paths through space. And just as there is no meaning to turning gears or pumps, neither is there any meaning, ultimately, to human life.

In this way, it should be clear that reductionism was what first sowed the seeds of our contemporary meaning crisis. With the rise of modern reductionistic science, humanity’s role in a divine saga was lost, and the perceived whole of conscious human life itself was reduced to its smallest parts—where one no longer finds any meaning, only law.

This idea continues to reverberate and resonate today. Millions of despairing souls still believe it—and it is driving them to the nihilistic conclusions nascent in it. Until, at last, here we are: We have become parts without a whole, at the same time that we cannot even claim to be whole ourselves.

Our lives lack the larger context of a cosmic story in which we play an important causal role. Nor can we even claim to be genuine agents with volitional integrity, since our wills and even our conscious awareness itself are merely “epi-phenomenal” illusions: vestigial byproducts of particles acting in deterministic fashion deeper down.

By the dawn of the 19th century, through relentless differentiation of parts from the whole, modernity had revealed reality in all its countless sundered pieces. The subject had been cleaved from the objective world, value had been parsed from existence, and causation was sundered from conscious will to obtain only at the lowest material level of the universe.

If there were any “grand design,” it was no more than the indifferent mechanical workings of a clock—the sort which the modernist Robert Frost would evoke in a poem of modern alienation and nihilistic despair:

And further still at an unearthly height,One luminary clock against the skyProclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

No comments:

Post a Comment