CosmoEcological Civlizations - PostCapitalistic

Economies & Politics, Part 2a

Economies & Politics, Part 2a

by R.E. Slater

September 5, 2020

I hope to cover the basics of political/economic ideologies simply using relevant videos and standard Wikipedia articles to help frame out a futuristic look at where a Christian-based political economic might go. Generally I will use the idea of an ecological society for this near-term futuristic vision. I find it attainable, and if done right, reflective of human and environmental justice and equality. This then would also lead us into a some kind of mutually beneficial post-capitalistic paradigm again, reflective of Christian teachings related to God's Love, Jesus' practices and teachings, and the new kingdom ethic summarized on the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5 (see NASB text here)

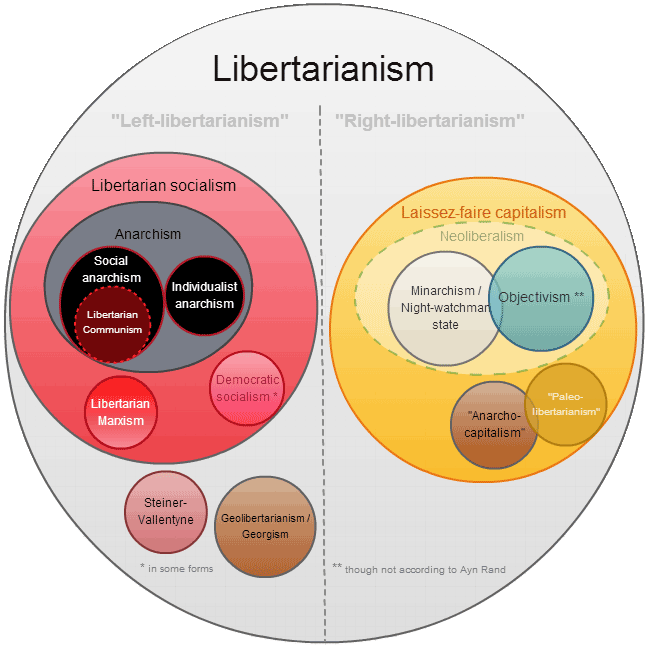

Part 1 will cover the basics of political economies. Initially I thought to ex-clude "libertarianism" for the simple reason that complex governments are here to stay and will require complex governmental solutions for poly-plural multi-ethnic societies. Libertarianism proposes small governments with less footprint which I find impractical, if not pure fantasy. However, locality (and meta-localities) will drive ecological societies and for this reason, along with the fact that libertarianism is a popular ideology I will lead off with it first after a general introductory video.

Part 2 will cover the basics of cultural philosophies such as modernism et al and where these cultural movements might be taking us. Having spent a large amount of time earlier this year speaking to the fundamentals of the universe using process philosophy the principles therewith will be used to help guide us toward a process-based futurism.

And finally, in Part 3, I will attempt to describe what future ecological civilizations may look like under a whole new kind of political-economic schema.

Soooo, here we go....

[The] Sermon on the Mount [is] a biblical collection of religious teachings and ethical sayings of Jesus of Nazareth, as found in Matthew, chapters 5–7. The sermon was addressed to disciples and a large crowd of listeners to guide them in a life of discipline based on a new law of love, even to enemies, as opposed to the old law of retribution. In the Sermon on the Mount are found many of the most familiar Christian homilies and sayings, including the Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer (qq.v.). - Encyc Britannica

Part 1 will cover the basics of political economies. Initially I thought to ex-clude "libertarianism" for the simple reason that complex governments are here to stay and will require complex governmental solutions for poly-plural multi-ethnic societies. Libertarianism proposes small governments with less footprint which I find impractical, if not pure fantasy. However, locality (and meta-localities) will drive ecological societies and for this reason, along with the fact that libertarianism is a popular ideology I will lead off with it first after a general introductory video.

Part 2 will cover the basics of cultural philosophies such as modernism et al and where these cultural movements might be taking us. Having spent a large amount of time earlier this year speaking to the fundamentals of the universe using process philosophy the principles therewith will be used to help guide us toward a process-based futurism.

And finally, in Part 3, I will attempt to describe what future ecological civilizations may look like under a whole new kind of political-economic schema.

Soooo, here we go....

Topics to be Covered

Part 1

Part 1

- Libertarianism

- (Classic, Enlightenment) Liberalism

- (Americanized) Modern Liberalism

- Social Liberalism

- Neo-Conservatism

- Conservatism

- Neo-Liberalism

- Summary 1 - Post-Capitalist Protestant View

- Summary 2 - Post-Capitalist Catholic View

Part 2

- Modernism

- Postmodernism

- Post-Postmodernism

- Hypermodernism

- Transmodernism

- Metamodernism

Part 3

- Post-Capitalism Economies

- CcosmoEcological Civilizations

Modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissance—in the "Age of Reason" of 17th-century thought and the 18th-century "Enlightenment". Some commentators consider the era of modernity to have ended by 1930, with World War II in 1945, or the 1980s or 1990s; the following era is called postmodernity. The term "contemporary history" is also used to refer to the post-1945 timeframe, without assigning it to either the modern or postmodern era. (Thus "modern" may be used as a name of a particular era in the past, as opposed to meaning "the current era".)

Depending on the field, "modernity" may refer to different time periods or qualities. In historiography, the 17th and 18th centuries are usually described as early modern, while the long 19th century corresponds to "modern history" proper. While it includes a wide range of interrelated historical processes and cultural phenomena (from fashion to modern warfare), it can also refer to the subjective or existential experience of the conditions they produce, and their ongoing impact on human culture, institutions, and politics (Berman 2010, 15–36).

As an analytical concept and normative ideal, modernity is closely linked to the ethos of philosophical and aesthetic modernism; political and intellectual currents that intersect with the Enlightenment; and subsequent developments such as existentialism, modern art, the formal establishment of social science, and contemporaneous antithetical developments such as Marxism. It also encompasses the social relations associated with the rise of capitalism, and shifts in attitudes associated with secularisation and post-industrial life (Berman 2010, 15–36).

By the late 19th and 20th centuries, modernist art, politics, science and culture has come to dominate not only Western Europe and North America, but almost every civilized area on the globe, including movements thought of as opposed to the West and globalization. The modern era is closely associated with the development of individualism,[1] capitalism,[2] urbanization[1] and a belief in the possibilities of technological and political progress.[3][4] Wars and other perceived problems of this era, many of which come from the effects of rapid change, and the connected loss of strength of traditional religious and ethical norms, have led to many reactions against modern development.[5][6] Optimism and belief in constant progress has been most recently criticized by postmodernism while the dominance of Western Europe and Anglo-America over other continents has been criticized by postcolonial theory.

In the view of Michel Foucault (1975) (classified as a proponent of postmodernism though he himself rejected the "postmodernism" label, considering his work as "a critical history of modernity"—see, e.g., Call 2002, 65), "modernity" as a historical category is marked by developments such as a questioning or rejection of tradition; the prioritization of individualism, freedom and formal equality; faith in inevitable social, scientific and technological progress, rationalization and professionalization, a movement from feudalism (or agrarianism) toward capitalism and the market economy, industrialization, urbanization and secularisation, the development of the nation-state, representative democracy, public education (etc.) (Foucault 1977, 170–77).

Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical movement and an art movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the newly emerging industrial world, including features such as urbanization, new technologies, and war. Artists attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction to "Make it new!" was the touchstone of the movement's approach.

Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream-of-consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, and divisionist painting. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism[a][2][3] and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody.[b][c][4] Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and many modernists also rejected religious belief.[5][d] A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art.[7]

While some scholars see modernism continuing into the 21st century, others see it evolving into late modernism or high modernism.[8] Postmodernism is a departure from modernism and rejects its basic assumptions.[9][10][11]

Definition

Some commentators define modernism as a mode of thinking—one or more philosophically defined characteristics, like self-consciousness or self-reference, that run across all the novelties in the arts and the disciplines.[12] More common, especially in the West, are those who see it as a socially progressive trend of thought that affirms the power of human beings to create, improve and reshape their environment with the aid of practical experimentation, scientific knowledge, or technology.[e] From this perspective, modernism encouraged the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was 'holding back' progress, and replacing it with new ways of reaching the same end. Others focus on modernism as an aesthetic introspection. This facilitates consideration of specific reactions to the use of technology in the First World War, and anti-technological and nihilistic aspects of the works of diverse thinkers and artists spanning the period from Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) to Samuel Beckett (1906–1989).[14][15][16][17][18]

According to Roger Griffin, modernism can be defined in a maximalist vision as a broad cultural, social, or political initiative, sustained by the ethos of "the temporality of the new". Modernism sought to restore, Griffin writes, a "sense of sublime order and purpose to the contemporary world, thereby counteracting the (perceived) erosion of an overarching ‘nomos’, or ‘sacred canopy’, under the fragmenting and secularizing impact of modernity." Therefore, phenomena apparently unrelated to each other such as "Expressionism, Futurism, vitalism, Theosophy, psychoanalysis, nudism, eugenics, utopian town planning and architecture, modern dance, Bolshevism, organic nationalism – and even the cult of self-sacrifice that sustained the hecatomb of the First World War – disclose a common cause and psychological matrix in the fight against (perceived) decadence." All of them embody bids to access a "supra-personal experience of reality", in which individuals believed they could transcend their own mortality, and eventually that they had ceased to be victims of history to become instead its creators.[19]

* * * * * * * * *

Postmodernity

Postmodernity (post-modernity or the postmodern condition) is the economic or cultural state or condition of society which is said to exist after modernity (In this context, "modern" is not used in the sense of "contemporary", but merely as a name for a specific period in history). Some schools of thought hold that modernity ended in the late 20th century – in the 1980s or early 1990s – and that it was replaced by postmodernity, and still others would extend modernity to cover the developments denoted by postmodernity, while some believe that modernity ended after World War II. The idea of the post-modern condition is sometimes characterized as a culture stripped of its capacity to function in any linear or autonomous state like regressive isolationism, as opposed to the progressive mind state of modernism.[1]

Postmodernity can mean a personal response to a postmodern society, the conditions in a society which make it postmodern or the state of being that is associated with a postmodern society as well as a historical epoch. In most contexts it should be distinguished from postmodernism, the adoption of postmodern philosophies or traits in the arts, culture and society. In fact, today, historical perspectives on the developments of postmodern art (postmodernism) and postmodern society (postmodernity) can be best described as two umbrella terms for processes engaged in an ongoing dialectical relationship like post-postmodernism, the result of which is the evolving culture of the contemporary world.[2]

Some commentators deny that modernity ended, and consider the post-WWII era to be a continuation of modernity, which they refer to as late modernity.

Uses of the term

Postmodernity is the state or condition of being postmodern – after or in reaction to that which is modern, as in postmodern art (see postmodernism). Modernity is defined as a period or condition loosely identified with the Progressive Era, the Industrial Revolution, or the Enlightenment. In philosophy and critical theory postmodernity refers to the state or condition of society which is said to exist after modernity, a historical condition that marks the reasons for the end of modernity. This usage is ascribed to the philosophers Jean-François Lyotard and Jean Baudrillard.

One "project" of modernity is said by Habermas to have been the fostering of progress by incorporating principles of rationality and hierarchy into public and artistic life. (See also postindustrial, Information Age.) Lyotard understood modernity as a cultural condition characterized by constant change in the pursuit of progress. Postmodernity then represents the culmination of this process where constant change has become the status quo and the notion of progress obsolete. Following Ludwig Wittgenstein's critique of the possibility of absolute and total knowledge, Lyotard further argued that the various metanarratives of progress such as positivist science, Marxism, and structuralism were defunct as methods of achieving progress.

The literary critic Fredric Jameson and the geographer David Harvey have identified postmodernity with "late capitalism" or "flexible accumulation", a stage of capitalism following finance capitalism, characterised by highly mobile labor and capital and what Harvey called "time and space compression". They suggest that this coincides with the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system which, they believe, defined the economic order following the Second World War. (See also consumerism, critical theory.)

Those who generally view modernity as obsolete or an outright failure, a flaw in humanity's evolution leading to disasters like Auschwitz and Hiroshima, see postmodernity as a positive development. Other philosophers, particularly those seeing themselves as within the modern project, see the state of postmodernity as a negative consequence of holding postmodernist ideas. For example, Jürgen Habermas and others contend that postmodernity represents a resurgence of long running counter-enlightenment ideas, that the modern project is not finished and that universality cannot be so lightly dispensed with. Postmodernity, the consequence of holding postmodern ideas, is generally a negative term in this context.

Postmodernism

Postmodernity is a condition or a state of being associated with changes to institutions and creations (Giddens, 1990) and with social and political results and innovations, globally but especially in the West since the 1950s, whereas postmodernism is an aesthetic, literary, political or social philosophy, the "cultural and intellectual phenomenon", especially since the 1920s' new movements in the arts. Both of these terms are used by philosophers, social scientists and social critics to refer to aspects of contemporary culture, economics and society that are the result of features of late 20th century and early 21st century life, including the fragmentation of authority and the commoditization of knowledge (see "Modernity").

The relationship between postmodernity and critical theory, sociology and philosophy is fiercely contested. The terms "postmodernity" and "postmodernism" are often hard to distinguish, the former being often the result of the latter. The period has had diverse political ramifications: its "anti-ideological ideas" appear to have been associated with the feminist movement, racial equality movements, gay rights movements, most forms of late 20th century anarchism and even the peace movement as well as various hybrids of these in the current anti-globalization movement. Though none of these institutions entirely embraces all aspects of the postmodern movement in its most concentrated definition they all reflect, or borrow from, some of its core ideas.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism is a broad movement that developed in the mid- to late 20th century across philosophy, the arts, architecture, and criticism, marking a departure from modernism. The term has been more generally applied to describe a historical era said to follow after modernity and the tendencies of this era.

Postmodernism is generally defined by an attitude of skepticism, irony, or rejection toward what it describes as the grand narratives and ideologies associated with modernism, often criticizing Enlightenment rationality and focusing on the role of ideology in maintaining political or economic power. Postmodern thinkers frequently describe knowledge claims and value systems as contingent or socially-conditioned, framing them as products of political, historical, or cultural discourses and hierarchies. Common targets of postmodern criticism include universalist ideas of objective reality, morality, truth, human nature, reason, science, language, and social progress. Accordingly, postmodern thought is broadly characterized by tendencies to self-consciousness, self-referentiality, epistemological and moral relativism, pluralism, and irreverence.

Postmodern critical approaches gained purchase in the 1980s and 1990s, and have been adopted in a variety of academic and theoretical disciplines, including cultural studies, philosophy of science, economics, linguistics, architecture, feminist theory, and literary criticism, as well as art movements in fields such as literature, contemporary art, and music. Postmodernism is often associated with schools of thought such as deconstruction, post-structuralism, and institutional critique, as well as philosophers such as Jean-François Lyotard, Jacques Derrida, and Fredric Jameson.

Criticisms of postmodernism are intellectually diverse and include arguments that postmodernism promotes obscurantism, is meaningless, and that it adds nothing to analytical or empirical knowledge.

Overview

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourse[1][2] defined by an attitude of skepticism toward what it describes as the grand narratives and ideologies of modernism, as well as opposition to epistemic certainty and the stability of meaning.[3] It questions or criticizes viewpoints associated with Enlightenment rationality dating back to the 17th century,[4] and is characterized by irony, eclecticism, and its rejection of the "universal validity" of binary oppositions, stable identity, hierarchy, and categorization.[5][6] Postmodernism is associated with relativism and a focus on ideology in the maintenance of economic and political power.[4] Postmodernists are generally "skeptical of explanations which claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races," and describe truth as relative.[7] It can be described as a reaction against attempts to explain reality in an objective manner by claiming that reality is a mental construct.[7] Access to an unmediated reality or to objectively rational knowledge is rejected on the grounds that all interpretations are contingent on when they are made;[8] as such, claims to objective fact are dismissed as "naive realism."[4]

Postmodern thinkers frequently describe knowledge claims and value systems as contingent or socially-conditioned, describing them as products of political, historical, or cultural discourses and hierarchies.[4] Accordingly, postmodern thought is broadly characterized by tendencies to self-referentiality, epistemological and moral relativism, pluralism, and irreverence.[4] Postmodernism is often associated with schools of thought such as deconstruction and post-structuralism.[4] Postmodernism relies on critical theory, which considers the effects of ideology, society, and history on culture.[9] Postmodernism and critical theory commonly criticize universalist ideas of objective reality, morality, truth, human nature, reason, language, and social progress.[4]

Initially, postmodernism was a mode of discourse on literature and literary criticism, commenting on the nature of literary text, meaning, author and reader, writing, and reading.[10] Postmodernism developed in the mid- to late-twentieth century across philosophy, the arts, architecture, and criticism as a departure or rejection of modernism.[11][12][12][13] Postmodernist approaches have been adopted in a variety of academic and theoretical disciplines, including political science,[14] organization theory,[15] cultural studies, philosophy of science, economics, linguistics, architecture, feminist theory, and literary criticism, as well as art movements in fields such as literature and music. As a critical practice, postmodernism employs concepts such as hyperreality, simulacrum, trace, and difference, and rejects abstract principles in favor of direct experience.[7]

Criticisms of postmodernism are intellectually diverse, and include arguments that postmodernism promotes obscurantism, is meaningless, and adds nothing to analytical or empirical knowledge.[16][17][18][19] Some philosophers, beginning with the pragmatist philosopher Jürgen Habermas, say that postmodernism contradicts itself through self-reference, as their critique would be impossible without the concepts and methods that modern reason provides.[3] Various authors have criticized postmodernism, or trends under the general postmodern umbrella, as abandoning Enlightenment rationalism or scientific rigor.[20][21]

* * * * * * * * *

|

| Believe Anything by Barbara Kruger at Hirshhorn, Washington, DC. Steve Rhodes |

|

| This sculpture by artist Jeff Koons, is post-modern because it copies a small object but blows it up out of proportion to cause the viewer to think of the object in a different way. |

The Post in

Post - a Latin prefix, meaning "behind" or "after." Therefore the definition of postmodernism should be a time after the modern age. But this sparks the question, when was this world modern? Do different regions of our globe experience a modern age while others are ahead or behind? Once postmodernism is supposedly reached, what more is there? This is why it's so difficult to grasp the concepts displayed in postmodern works, they redefine reality and one's personal truths. It's hard to see how can something be 'after modern' when it's unclear what was modern in the first place. These questions without answers seems to be the purpose of postmodern work. Making the viewer think of a deeper meaning that may or may not even exist. This 'post' in postmodernism could be interpreted as the aftermath of looking at postmodern art or stories. Either way, the complex questions and contradicting answers perfectly summarize the true affects of postmodernism without a defined modernism. - Anon

Post-postmodernism

Post - a Latin prefix, meaning "behind" or "after." Therefore the definition of postmodernism should be a time after the modern age. But this sparks the question, when was this world modern? Do different regions of our globe experience a modern age while others are ahead or behind? Once postmodernism is supposedly reached, what more is there? This is why it's so difficult to grasp the concepts displayed in postmodern works, they redefine reality and one's personal truths. It's hard to see how can something be 'after modern' when it's unclear what was modern in the first place. These questions without answers seems to be the purpose of postmodern work. Making the viewer think of a deeper meaning that may or may not even exist. This 'post' in postmodernism could be interpreted as the aftermath of looking at postmodern art or stories. Either way, the complex questions and contradicting answers perfectly summarize the true affects of postmodernism without a defined modernism. - Anon

Post-postmodernism

Post-postmodernism is a wide-ranging set of developments in critical theory, philosophy, architecture, art, literature, and culture which are emerging from and reacting to postmodernism. Another similar recent term is metamodernism.

Periodization

Most scholars would agree that modernism began around 1900 and continued on as the dominant cultural force in the intellectual circles of Western culture well into the mid-twentieth century.[1] Like all eras, modernism encompasses many competing individual directions and is impossible to define as a discrete unity or totality. However, its chief general characteristics are often thought to include an emphasis on "radical aesthetics, technical experimentation, spatial or rhythmic, rather than chronological form, [and] self-conscious reflexiveness"[2] as well as the search for authenticity in human relations, abstraction in art, and utopian striving. These characteristics are normally lacking in postmodernism or are treated as objects of irony.

Postmodernism arose after World War II as a reaction to the perceived failings of modernism, whose radical artistic projects had come to be associated with totalitarianism[3] or had been assimilated into mainstream culture. The basic features of what we now call postmodernism can be found as early as the 1940s, most notably in the work of Jorge Luis Borges.[4] However, most scholars today would agree that postmodernism began to compete with modernism in the late 1950s and gained ascendancy over it in the 1960s.[5] Since then, postmodernism has been a dominant, though not undisputed, force in art, literature, film, music, drama, architecture, history, and continental philosophy. Salient features of postmodernism are normally thought to include the ironic play with styles, citations and narrative levels,[6] a metaphysical skepticism or nihilism towards a "grand narrative" of Western culture,[7] a preference for the virtual at the expense of the real (or more accurately, a fundamental questioning of what 'the real' constitutes)[8] and a "waning of affect"[9] on the part of the subject, who is caught up in the free interplay of virtual, endlessly reproducible signs inducing a state of consciousness similar to schizophrenia.[10]

Since the late 1990s there has been a small but growing feeling both in popular culture and in academia that postmodernism "has gone out of fashion."[11] However, there have been few formal attempts to define and name the era succeeding postmodernism, and none of the proposed designations has yet become part of mainstream usage.

Definitions

Consensus on what constitutes an era can not be easily achieved while that era is still in its early stages. However, a common theme of current attempts to define post-postmodernism is emerging as one where faith, trust, dialogue, performance, and sincerity can work to transcend postmodern irony. The following definitions, which vary widely in depth, focus, and scope, are listed in the chronological order of their appearance.

Turner's post-postmodernism

In 1995, the landscape architect and urban planner Tom Turner issued a book-length call for a post-postmodern turn in urban planning.[12] Turner criticizes the postmodern credo of "anything goes" and suggests that “the built environment professions are witnessing the gradual dawn of a post-Postmodernism that seeks to temper reason with faith.”[13] In particular, Turner argues for the use of timeless organic and geometrical patterns in urban planning. As sources of such patterns he cites, among others, the Taoist-influenced work of the American architect Christopher Alexander, gestalt psychology and the psychoanalyst Carl Jung's concept of archetypes. Regarding terminology, Turner urges us to "embrace post-Postmodernism – and pray for a better name."[14]

Epstein's trans-postmodernism

In his 1999 book on Russian postmodernism the Russian-American Slavist Mikhail Epstein suggested that postmodernism "is ... part of a much larger historical formation," which he calls "postmodernity".[15] Epstein believes that postmodernist aesthetics will eventually become entirely conventional and provide the foundation for a new, non-ironic kind of poetry, which he describes using the prefix "trans-":

As an example Epstein cites the work of the contemporary Russian poet Timur Kibirov.[17]

Gans' post-millennialism

The term post-millennialism was introduced in 2000 by the American cultural theorist Eric Gans[18] to describe the era after postmodernism in ethical and socio-political terms. Gans associates postmodernism closely with "victimary thinking," which he defines as being based on a non-negotiable ethical opposition between perpetrators and victims arising out of the experience of Auschwitz and Hiroshima. In Gans's view, the ethics of postmodernism is derived from identifying with the peripheral victim and disdaining the utopian center occupied by the perpetrator. Postmodernism in this sense is marked by a victimary politics that is productive in its opposition to modernist utopianism and totalitarianism but unproductive in its resentment of capitalism and liberal democracy, which he sees as the long-term agents of global reconciliation. In contrast to postmodernism, post-millennialism is distinguished by the rejection of victimary thinking and a turn to "non-victimary dialogue"[19] that will "diminish ... the amount of resentment in the world."[20] Gans has developed the notion of post-millennialism further in many of his internet Chronicles of Love and Resentment[21] and the term is allied closely with his theory of generative anthropology and his scenic concept of history.[22]

Kirby's pseudo-modernism or digimodernism

In his 2006 paper The Death of Postmodernism and Beyond, the British scholar Alan Kirby formulated a socio-cultural assessment of post-postmodernism that he calls "pseudo-modernism".[23] Kirby associates pseudo-modernism with the triteness and shallowness resulting from the instantaneous, direct, and superficial participation in culture made possible by the internet, mobile phones, interactive television and similar means: "In pseudo-modernism one phones, clicks, presses, surfs, chooses, moves, downloads."[23]

Pseudo-modernism's "typical intellectual states" are furthermore described as being "ignorance, fanaticism and anxiety" and it is said to produce a "trance-like state" in those participating in it. The net result of this media-induced shallowness and instantaneous participation in trivial events is a "silent autism" superseding "the neurosis of modernism and the narcissism of postmodernism." Kirby sees no aesthetically valuable works coming out of "pseudo-modernism". As examples of its triteness he cites reality TV, interactive news programs, "the drivel found ... on some Wikipedia pages", docu-soaps, and the essayistic cinema of Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock.[23] In a book published in September 2009 titled Digimodernism: How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure our Culture, Kirby developed further and nuanced his views on culture and textuality in the aftermath of postmodernism.

Vermeulen and van den Akker's metamodernism

In 2010 the cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker introduced the term metamodernism [24] as an intervention in the post-postmodernism debate. In their article "Notes on Metamodernism" they assert that the 2000s are characterized by the emergence of a sensibility that oscillates between, and must be situated beyond, modern positions and postmodern strategies. As examples of the metamodern sensibility Vermeulen and van den Akker cite the "informed naivety", "pragmatic idealism" and "moderate fanaticism" of the various cultural responses to, among others, climate change, the financial crisis, and (geo)political instability.

|

| click here to enlarge |