Maybe you've seen the editorial cartoon by Bruce MacKinnon that depicts

Lady Justice being held down and muzzled by well-dressed thugs from the GOP.

It was drawn in response to Brett Kavanaugh's confirmation hearing, during which Republican senators were working hard to brush away the testimony of

Christine Blasey Ford about Kavanaugh's character (or lack thereof), but the instantly classic cartoon can easily stand apart from the specific circumstances of its creation — Lady Justice being assaulted by white male members of the Republican Party.

In a

recent interview with Ezra Klein for his podcast, legal scholar Larry Kramer discusses how liberals, after a series of progressive decisions by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, began to rely too much on the courts and too little on politics, while the right methodically mounted a political counterrevolution, one that included redeployment of the judicial review philosophy known as "originalism."

Constitutional textualists — who formerly claimed to be wedded to the letter of the law — became originalists (or was it the other way around?), delving beneath the text itself for deeper meanings, sometimes in search of the founders' intent and sometimes to ascertain (as they claimed) how the text would have been understood by reasonable people at the time it was written. People, say, like the town blacksmith or the chandler chasing a chicken in the street, who would likely have given little thought to, say, the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection under the law, even in terms of the big issues of their time.

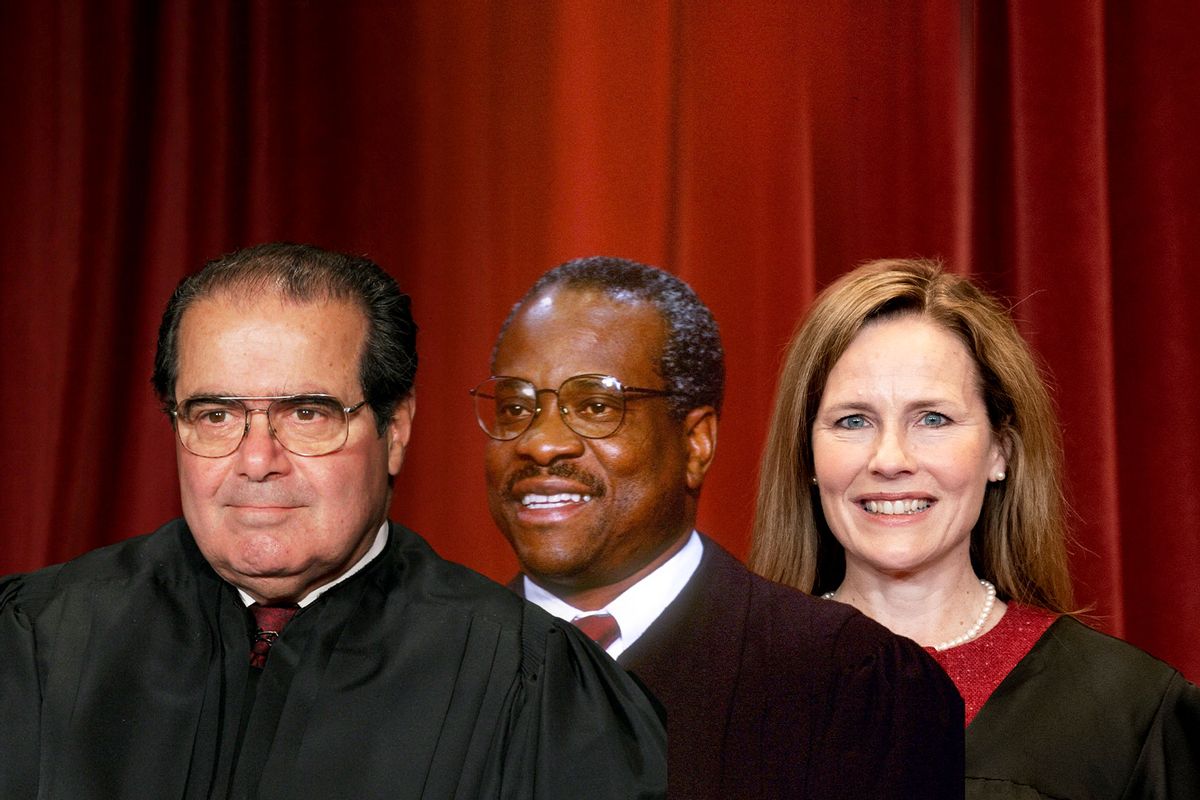

The truth is that so-called modern originalists or textualists, like the late Justice Antonin Scalia or his intellectual heirs Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett, also feel free to roam much farther afield than that, seeking justifications for their favored interpretation in English common law and philosophy.

As utilized by the so-called conservatives on the current court, textualism and originalism have become ways to muzzle the voice of the Constitution and keep it from rising from its

draped featherbed to address the pressing issues of our own time (when, you know, our beds are often ordered online because we heard about them on a podcast).

But is the use of the term "originalism" by Scalia and his acolytes itself actually disingenuous?

That's the argument of Praveen Fernandes of the

Constitutional Accountability Center, who suggests that a true originalist approach to interpreting the Constitution would not provide conservative results, because the document is, on the whole, remarkably progressive. Instead, Fernandes says, judicial conservatives distorting the meaning of the Constitution by practicing

fauxriginalism:

[P]rogressives have not been fighting originalism; we have been fighting fauxriginalism. Fauxriginalism distorts the meaning of the Constitution, often by focusing selectively on some parts of the document, rather than by looking at the text, history, and values of the whole Constitution. Conservatives like to claim that originalism leads them to conservative results, but that's because they too often give a cramped meaning to the Constitution's text and ignore the constitutional history and values that help elucidate what that text means. In truth, conservatives have been a bit like the kid in our grade school class who delivered a book report, but who had only read the first chapters of the book — and didn't even read them that carefully.

I'm reminded that we used to joke about something we called the "scholarly bluff," where you regurgitate a quote from a recognizable (but perhaps not too recognizable) name to end an argument. We laughed about it because it was so simple — and so effective. Your quote might not actually support your argument, and you might not even have gotten it right. But people tended to back down in the face of such seeming erudition.

Given that the overtly anti-federalist Federalist Society was itself

disingenuously named, it figures that it would get behind a disingenuous form of originalism. In a recent

column for the Nation, Elie Mystal writes that the nature of conservative justices began to change after 1992, when fundamentalist Christians were deeply disappointed by the Planned Parenthood of Southern Pennsylvania v. Casey ruling:

The principal difference between conservative justices then and conservative justices now is that the conservatives of 30 years ago were practical. They didn't like abortions, but they understood that no society in history had successfully prevented them. They understood that criminalizing doctors who can perform the procedures safely only leads to unsafe, unregulated procedures. They understood that pregnant people will seek control over their own bodies, whether or not the state or the courts or the church acknowledges their bodily autonomy.

But such practical-minded conservative justices were replaced by shameless political ideologues and, more recently, by religious zealots — indoctrinated, vetted and even prepped for perjury by the Federalist Society.

Mystal likens the extremists on the current court to an invasive species that was purposely introduced into a local ecosystem to address some specific problem, but then ran amok. Now that they have thoroughly devoured Roe v. Wade, they're eager to turn their attention to other prey, such as the separation of church and state. Mystal says affirmative action is next.

The only solution, he writes, is for Democrats to meet the challenge by changing the nature of the court. "After 1992, Republicans engineered a new breed of conservative justice. The rest of us must create a new kind of Supreme Court before it's too late."

On Klein's podcast, Kramer notes a few ways the court could be changed to reduce the effect of the ideology of individual justices. He also asserts that the Constitution is a progressive document, something liberals should be talking up a great deal more in the face of the ever more constrained view from the right.

As used by so-called conservatives, "textualism" and "originalism" are tools to muzzle the Constitution's true voice, and prevent it from addressing the issues of our time.

How progressive is it really? According to scholar Garry Wills, the

Establishment Clause alone was a defining miracle of the U.S. Constitution. As James Madison wrote in his "

Memorial and Remonstrance" statement on church and state, disestablishment both protected the free expression of religion and protected all citizens from the use of "Religion as an engine of Civil policy." In a

letter to Madison, Thomas Jefferson argued that as the earth belongs to the living, any constitution (not just ours) was a living document, something that needed to be updated frequently as society evolved.

As for the ideological and religious warriors on the current court (who would make Madison shudder), do yourself a favor and listen to the

entire podcast. Two quotes from Kramer stood out for me:

"If the founding generation had been originalists, we wouldn't be here," and "The only way you can be an originalist is to be a really, really bad historian."

Unless you believe, that is, that the Constitution is indeed a progressive document and that a truly originalist interpretation demands an expansive view of the founding principles of the framework. As Kramer says, conservatives should never have been allowed to occupy the Constitution and claim it as their totem, the same way they have done for so long with the flag and the concept of patriotism. Supporters of the ongoing Big Lie about the 2020 election and the Jan. 6 insurrection cannot claim patriotism; those who are fine with the Confederate flag being paraded through the Capitol cannot claim allegiance to our nation's actual flag.

It's all been an endless con, since the days of Ronald Reagan, in service to giving more to the wealthy and big corporations while dividing the citizens from one another, mostly over culture-war issues the powerful don't much care about. (Americans used to be proud to mind their own business.)

Now the idea is to "flood the zone" with nonsense in order to keep the public from noticing our nation's

astonishing levels of income inequality, to dumb children down further, to install permanent minority rule and to shut down the American experiment once and for all.

As both Mystal and Kramer note, we need to work toward a new kind of Supreme Court, one less dominated by political ideology and religious dogma. That won't be easy, but if we don't, MacKinnon's tragic vision of Lady Liberty will be all too accurate — with the dire human costs afflicting many generations to come.

* * * * * * * * *

|

Image: Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Cameron Smith /

Mohammad Aqhib / Unsplash / Reza Estakhrian / Getty Images |

What Is Christian Nationalism?

An explainer on how the belief differs from other forms of

nationalism, patriotism, and Christianity.

by Paul Miller

February 3, 2021

You’ve probably seen headlines recently about the evils of Christian nationalism, especially since December’s Jericho March in Washington, DC, and since a mob of Trump supporters—many sporting Christian signs, slogans, or symbols—rioted and stormed the US Capitol building on January 6.

What is Christian nationalism, and how is it different from Christianity? How is it different from patriotism? How should Christians think about nations, especially about the United States? If nationalism is bad, does that mean we should reject nationality and national loyalty altogether?

What is patriotism, and is it good?

Patriotism is the love of country. It is different from nationalism, which is an argument about how to define our country. Christians should recognize that patriotism is good because all of God’s creation is good and patriotism helps us appreciate our particular place in it. Our affection and loyalty to a specific part of God’s creation helps us do the good work of cultivating and improving the part we happen to live in. As Christians, we can and should love the United States—which also means working to improve our country by holding it up for critique and working for justice when it errs.

What is nationalism?

There are many definitions of nationalism and an active debate about how best to define it. I reviewed the standard academic literature on nationalism and found several recurring themes. Most scholars agree that nationalism starts with the belief that humanity is divisible into mutually distinct, internally coherent cultural groups defined by shared traits like language, religion, ethnicity, or culture. From there, scholars say, nationalists believe that these groups should each have their own governments; that governments should promote and protect a nation’s cultural identity; and that sovereign national groups provide meaning and purpose for human beings.

What is Christian nationalism?

Christian nationalism is the belief that the American nation is defined by Christianity, and that the government should take active steps to keep it that way. Popularly, Christian nationalists assert that America is and must remain a “Christian nation”—not merely as an observation about American history, but as a prescriptive program for what America must continue to be in the future. Scholars like Samuel Huntington have made a similar argument: that America is defined by its “Anglo-Protestant” past and that we will lose our identity and our freedom if we do not preserve our cultural inheritance.

Christian nationalists do not reject the First Amendment and do not advocate for theocracy, but they do believe that Christianity should enjoy a privileged position in the public square. The term “Christian nationalism,” is relatively new, and its advocates generally do not use it of themselves, but it accurately describes American nationalists who believe American identity is inextricable from Christianity.

What is the problem with nationalism?

Humanity is not easily divisible into mutually distinct cultural units. Cultures overlap and their borders are fuzzy. Since cultural units are fuzzy, they make a poor fit as the foundation for political order. Cultural identities are fluid and hard to draw boundaries around, but political boundaries are hard and semipermanent. Attempting to found political legitimacy on cultural likeness means political order will constantly be in danger of being felt as illegitimate by some group or other. Cultural pluralism is essentially inevitable in every nation.

Is that really a problem, or just an abstract worry?

It is a serious problem. When nationalists go about constructing their nation, they have to define who is, and who is not, part of the nation. But there are always dissidents and minorities who do not or cannot conform to the nationalists’ preferred cultural template. In the absence of moral authority, nationalists can only establish themselves by force. Scholars are almost unanimous that nationalist governments tend to become authoritarian and oppressive in practice. For example, in past generations, to the extent that the United States had a quasi-established official religion of Protestantism, it did not respect true religious freedom. Worse, the United States and many individual states used Christianity as a prop to support slavery and segregation.

What do Christian nationalists want that is different from normal Christian engagement in politics?

Christian nationalists want to define America as a Christian nation and they want the government to promote a specific cultural template as the official culture of the country. Some have advocated for an amendment to the Constitution to recognize America’s Christian heritage, others to reinstitute prayer in public schools. Some work to enshrine a Christian nationalist interpretation of American history in school curricula, including that America has a special relationship with God or has been “chosen” by him to carry out a special mission on earth. Others advocate for immigration restrictions specifically to prevent a change to American religious and ethnic demographics or a change to American culture. Some want to empower the government to take stronger action to circumscribe immoral behavior.

Some—again, like the scholar Samuel Huntington—have argued that the United States government must defend and enshrine its predominant “Anglo-Protestant” culture to ensure the survival of American democracy. And sometimes Christian nationalism is most evident not in its political agenda, but in the sort of attitude with which it is held: an unstated presumption that Christians are entitled to primacy of place in the public square because they are heirs of the true or essential heritage of American culture, that Christians have a presumptive right to define the meaning of the American experiment because they see themselves as America’s architects, first citizens, and guardians.

How is this dangerous for America?

Christian nationalism tends to treat other Americans as second-class citizens. If it were fully implemented, it would not respect the full religious liberty of all Americans. Empowering the state through “morals legislation” to regulate conduct always carries the risk of overreaching, setting a bad precedent, and creating governing powers that could be used later be used against Christians. Additionally, Christian nationalism is an ideology held overwhelmingly by white Americans, and it thus tends to exacerbate racial and ethnic cleavages. In recent years, the movement has grown increasingly characterized by fear and by a belief that Christians are victims of persecution. Some are beginning to argue that American Christians need to prepare to fight, physically, to preserve America’s identity, an argument that played into the January 6 riot.

How is Christian nationalism dangerous to the church?

Christian nationalism takes the name of Christ for a worldly political agenda, proclaiming that its program is the political program for every true believer. That is wrong in principle, no matter what the agenda is, because only the church is authorized to proclaim the name of Jesus and carry his standard into the world. It is even worse with a political movement that champions some causes that are unjust, which is the case with Christian nationalism and its attendant illiberalism. In that case, Christian nationalism is calling evil good and good evil; it is taking the name of Christ as a fig leaf to cover its political program, treating the message of Jesus as a tool of political propaganda and the church as the handmaiden and cheerleader of the state.

How is Christianity different from Christian nationalism?

Christianity is a religion focused on the person and work of Jesus Christ as defined by the Christian Bible and the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds. It is the gathering of people “from every nation and tribe and people and language,” who worship Jesus (Rev. 7:9), a faith that unites Jews and Greeks, Americans and non-Americans together. Christianity is political, in the sense that its adherents have always understood their faith to challenge, affect, and transcend their worldly loyalties—but there is no single view on what political implications flow from Christian faith other than that we should “fear God, honor the king” (1 Pet. 2:17, NASB), pay our taxes, love our neighbors, and seek justice.

Christian nationalism is, by contrast, a political ideology focused on the national identity of the United States. It includes a specific understanding of American history and American government that are, obviously, extrabiblical—an understanding that is contested by many historians and political scientists. Most importantly, Christian nationalism includes specific policy prescriptions that it claims are biblical but are, at best, extrapolations from biblical principles and, at worst, contradictory to them.

Can Christians be politically engaged without being Christian nationalists?

Yes. American Christians in the past were exemplary in helping establish the American experiment, and many American Christians worked to end slavery and segregation and other evils. They did so because they believed Christianity required them to work for justice. But they worked to advance Christian principles, not Christian power or Christian culture, which is the key distinction between normal Christian political engagement and Christian nationalism. Normal Christian political engagement is humble, loving, and sacrificial; it rejects the idea that Christians are entitled to primacy of place in the public square or that Christians have a presumptive right to continue their historical predominance in American culture. Today, Christians should seek to love their neighbors by pursuing justice in the public square, including by working against abortion, promoting religious liberty, fostering racial justice, protecting the rule of law, and honoring constitutional processes. That agenda is different from promoting Christian culture, Western heritage, or Anglo-Protestant values.

Paul D. Miller is a professor of the practice of international affairs at Georgetown University and a research fellow with the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.