Process Evolution is "How everything

relates to everything else"

- re slater

Having recently reviewed and written about process philosophy over the past several months I would like to apply its concept to all previous articles on evolution I have written on this website. It is a necessary ingredient to any understanding of evolution whether from a religious or non-religious viewpoint. Its principle aptly describes what science has been studying.

When googling "process evolution" I mainly found articles applying the term to business systems but very little, if any, coupling the idea of process philosophy / process theology to Darwinian evolution. However, it would be right to apply the one with the other when thinking how the "circle of life" intricately relates from its whole to its parts and back again.

I think Alfred North Whitehead might describe process evolution as that preceding congeal of actual entities or actual occasions affecting and intermixing with one another as to led to endless outcomes of novelty where each actuality concresces towards another affected and evolving actuality leading to generative, valuative events of becoming.

In terms of Process Theology, God is the unique and initiating Actuality or Occasion who births all succeeding novel actualities and occasions. These events are unique and unrepeatable as well as connective to all previous and succeeding events. It answers the question why quantum particles are strangely connected to each other when separated at great distances. It also speaks to why all of the cosmos, the universe, nature, and life are so intimately bound together with one another.

Whitehead described this idea as the "process of organism" which is commonly known today as process thought or process philosophy. He was looking to circumscribed all previous philosophical discussions within a holistic circle of "beingness" or "eventness" so that when done he had completed what we think of today as "the circle of life".

Process Philosophy is holistic metaphysic which saw all parts of creation as related to the whole of creation, and the whole as related back to its parts. Thus, previous philosophers were simply describing reflective "parts" to the "whole" of the metaphysical world surrounding their observations much like describing the proverbial elephant in the room but not necessarily the elephant (sic, the metaphysic) itself.

Besides Whitehead, Baidou, and Deluze write in similar fashion of "Being and Event" but in Whitehead he uplifts the discussion towards the fuller idea of "Becoming" wherein a divine process is initiated from God's Being or Essence leading to valuative (better described as generative) becoming. When this fails, both inorganically or organically, it is because of the freedom of agency God has gifted creation.

Thus, what we may describe as sin or evil, suffering or harm, is in another sense a result of agency granted creation from a good and loving God. One might describe it as a "fearsome gift" as portrayed in the Adam-Eve-Serpent legend of the Bible wherein all things changed with its taking. In all respects freewill is thus birthed from God's Essence as a good and perfect and loving quality to take into life with each succeeding derivation.

However, when given agency, any unloving, or ungood, disruption is a result of the creative freewill. That is, freewill is a gift granted by uncontrolling divine action allowing a fully free and open future without determination. It was birthed from God's love, not by fiat nor command. That is, as God is free in His agency so too He endowed His creation with that same agency which bore from His divine image. Freewill is, because God is. It did not require a special command to do so; it resulted naturally from God's Being or Essence into creation's being or essence. Thus, God's agency grants all recipients - from quantum forces to living hearts - with endless generative possibilities for goodness and love, positive creativity and constructive novelty.

On the inorganic level we might describe disruptive agency as chaotic randomness if, and when, it creates negative disruptive events within the human purview of life (such as destructive flooding or winds) or nature's reaction to events in its life (such as pollution). But as a process theologian I must insist on the principle of chaotic randomness for a freewill creation to function lest it loses its ability to retain its creative novelty.

Let me explain. Originally the primal earth was filled with methane gas wherein organic life thrived. Later, the gas of oxygen began to replace methane gas. Oxygen was lethal to methane-base organisms. As oxygen expanded to replace methane so old life forms died out. In their place new forms of life resulted which thrived on oxygen - even as methane became lethal to those oxygen-based organisms. The life forms had effectively switched with one another as their environments changed.

This is the beauty of evolution. Life will find a way to survive against all odds. Yet underneath it must lie that generative (and regenerating) principle of chaotic randomness (we know these as Darwinian mutations) without which the life cycles of persistent change would be permanently disrupted thus ending any cycles of life. As such, I find the evolutionary perspective to be quite helpful in representing the sublime feature of process philosophy as relentlessly explorative against all chaotic events leading towards ungenerative becoming.

That chaotic randomness is a necessary ingredient to the circle of life must also be the case lest Whiteheadian process becomes a deniable conjecture. This type of agency must therefore include the event of death. Without cycles of life-and-death there can be no perishable, succeeding actualities. This is the very basis of process thought as perishing entities and occasions prehend future passing forms of actuality in the intermix of relational continuities and discontinuities of actualized communities.

Essentially, Darwinian evolution has captured the essence of the necessary (mutating) life-and-death cycles of creation as a redeemable quality of seeming disruptions birthing-and-rebirthing time-and-again life's struggle for beingness, novelty, and becoming. Its concept is part-and-parcel of process philosophy's overall observation of the world and any future worlds to come.

On the organic level of sentient beings, the clearer idea of sin and evil can more easily be conveyed by the actions we take with one another. We are created to love and bring goodness, novelty and wellbeing into this life. When not, when acting un-Godlike, we fail in our generative or, valuative, purpose of living.

The remaining sections of this post will show how other theologians, scientists, physicists, and engineers are thinking about process evolution related to their fields of interest. Overall, the idea that all things are related to all things is but a beginning point in describing a generative teleology or purposeful result of the evolutionary process of the circle of life.

R.E. Slater

May 7, 2020

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Evolution and Process Thought

Pages 161-178 | Published online: 18 Feb 2007

Five topics arising from evolutionary biology open new possibilities for fruitful dialogue between scientists and proponents of the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. These topics (with the main authors whose views are discussed) are:

(1) Contingency and Teleology, Stephen Jay Gould, Simon Conway Morris;

(2) The Baldwin Effect and Interiority, Bruce Weber and David DePew, Daniel Dennett, Terrence Deacon, Susan Oyama;

(3) Complexity and Design, Michael Behe, David Griffin;

(4) Hierarchical Levels and Downward Causation, Theo Meyering, Charles Hartshorne; and,

(5) Self-organization and Emergence, Terrence Deacon, Philip Clayton.

In the final section, I look at the relation of science and metaphysics and ask whether the subjectivity postulated by process philosophy is accessible to scientific investigation.

Notes

Julian Huxley, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis (London: Allen & Unwin, 1942); Gaylord G. Simpson, The Meaning of Evolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949).

S. J. Gould and N. Eldredge, “Punctuated Equilibria,” Paleobiology 3 (1977): 115 – 151; S. J. Gould and R. C. Lewontin, “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptionist Programme,” Proc. of Royal Society of London B 205 (1979): 581 – 598; S. J. Gould, “Darwinism and the Expansion of Evolutionary Theory,” Science 216 (1982): 380 – 387.

G. Ledyard Stebbins and Francisco J. Ayala, “Is a New Evolutionary Synthesis Necessary?” Science 213 (1981): 167 – 171 and “The Evolution of Darwinism,” Scientific American 253 (July 1885): 72 – 89.

Thomas J. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970).

Imre Lakatos, “Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes,” in Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, eds Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

See Ian G. Barbour, Myths, Models and Metaphors (London: SCM Press, 1974); Nancy Cartwright, The Dappled World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Stephen Jay Gould, Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (New York: Norton, 1989).

Simon Conway Morris, The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1998). See also the exchange between Gould and Conway Morris in Natural History 107 (1998): 48 – 55.

Simon Conway Morris, Life's Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Conway Morris, Life's Solution, 124.

Conway Morris, Life's Solution, 328.

Simon Conway Morris, “The Paradoxes of Evolution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe?” in God and Design: The Teleological Argument and Modern Science, ed. Neil A. Manson (London: Routledge, 2003), 334.

Ian G. Barbour, Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997), 293 – 297.

Bruce Weber and David Depew, Evolution and Learning: The Baldwin Effect Reconsidered (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

J. M. Baldwin, “A New Factor in Evolution,” American Naturalist 30 (1986): 441 – 451, and Development and Evolution (New York: Macmillan, 1902). See also Robert J. Richards, Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behavior (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), chap. 10.

C. H. Waddington, Organisers and Genes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940) and The Strategy of the Genes (New York: Macmillan, 1957).

Daniel Dennett, “The Baldwin Effect: A Crane, Not a Skyhook,” in Weber and Depew, op. cit.

Daniel Dennett, Darwin's Dangerous Idea (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 77 (his emphasis).

Terrence W. Deacon, “Multilevel Selection in a Complex Adaptive System: The Problem of Language Origin,” and “The Hierarchic Logic of Emergence: Untangling the Interdependence of Evolution and Self-organization,” in Weber and Depew, op. cit.

Terrence W. Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Coevolution of Language and Brain (New York: Norton, 1997).

Gerald W. Edelman, Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

Susan Oyama, “On Having a Hammer,” in Weber and Depew, op.cit.

David Ray Griffin, “Some Whiteheadian Comments,” in Mind and Nature: Essays on the Interface of Science and Philosophy, ed. John Cobb, Jr and David Ray Griffin (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1977).

David Ray Griffin, Religion and Scientific Naturalism (Albany: State Univ. of New York Press, 2000), 299.

Ibid, 299.

Michael Behe, Darwin's Black Box (New York: Free Press, 1998).

Griffin, Religion and Scientific Naturalism, 287, footnote 23.

Collections of essays for and against Intelligent Design are given in ed., Neil A. Manson, God and Design: The Teleological Argument and Modern Science (London and New York: Routledge, 2003) and ed., Roland T. Pennock, Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics: Philosophical, Theological and Scientific Perspectives (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001). A bibliography of recent articles can be found on website of the National Center for Science Education at www.ncseweb.org

Kenneth Miller, “Answering the Biological Argument from Design” in Neil A. Manson, ed., op. cit.

Griffin, op. cit., 289 (quoting William Thorpe).

Symposium on “Life and the Art of Networks,” Science 30 (26 Sept. 2003): 1863 – 1874.

See Steven Johnson, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software (New York: Scribner, 2001).

Ian G. Barbour, Issues in Science and Religion (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1966), 327 – 337 and Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues, 230 – 235. See also, Francisco J. Ayala, “Introduction” in The Problem of Reduction, ed. F. Ayala and T. Dobzhansky (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1974).

On top-down causation, see Arthur Peacocke, Theology for a Scientific Age, enlarged ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), chap. 3.

Theo Meyering, “Downward Causation,” in Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, ed. J. Wentzel Vrede van Huysteen (New York: Macmillan Reference, 2003), 229.

Charles Hartshorne, Reality as Social Process (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1953), chap. 1 and The Logic of Perfection (LaSalle, Ill: Open Court, 1962), chap. 7.

Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers, Order out of Chaos: Man's New Dialogue with Nature (New York: Bantam Books, 1984).

Stuart Kaufman, At Home in the Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Terrence W. Deacon, “The Hierarchic Logic of Emergence” in Weber and Depew, op. cit.

Bruce H. Weber and Terrence W. Deacon, “Thermodynamic Cycles, Developmental Systems, and Emergence,” Cybernetics and Human Knowing 7:1 (2000): 21 – 43.

Philip Clayton, “Neuroscience, the Person, and God: An Emergentist Account” in Neuroscience and the Person: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action, eds. Robert John Russell, Nancey Murphy, Theo C. Meyering and Michael Arbib (Vatican City State: Vatican Observatory and Berkeley, CA: Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, 1999).

Philip Clayton, “The Emergence of Spirit,” CTNS Bulletin 20:4 (Fall 2000): 3 – 20.

Ibid., 15.

Clayton, “Neuroscience, the Person, and God,” in Russell et al, op. cit., 211.

Philip Clayton, “Barbour's Panentheistic Metaphysics,” in Fifty Years in Science and Religion: Ian Barbour and His Legacy, ed. Robert John Russell (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004).

Ian G. Barbour, Nature, Human Nature, and God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), 37.

Ian G. Barbour, “God's Power: A Process View,” in The Work of Love: Creation as Kenosis, ed. John Polkinghorne (London: SPCK, 2001).

Clayton, “Barbour's Panentheistic Metaphysics,” in Russell, 113 – 115.

Ian G. Barbour, Myths, Models, and Paradigms (London: SCM Press, 1974).

Clayton, “The Emergence of the Spirit”, 6.

Barbour, Religion and Science, p. 290; Nature, Human Nature, and God, 37, 99.

Barbour, Nature, Human Nature, and God, 99.

Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1938), 211.

John F. Haught, God After Darwin: A Theology of Evolution (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2000), 178, 179.

David Ray Griffin, “On Ian Barbour's Issues in Science and Religion,” Zygon 23 (1988): 57 – 81.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

This awesome graphic of all lifeforms

will make you feel tiny

by Jennifer Welsh

May 27, 2015

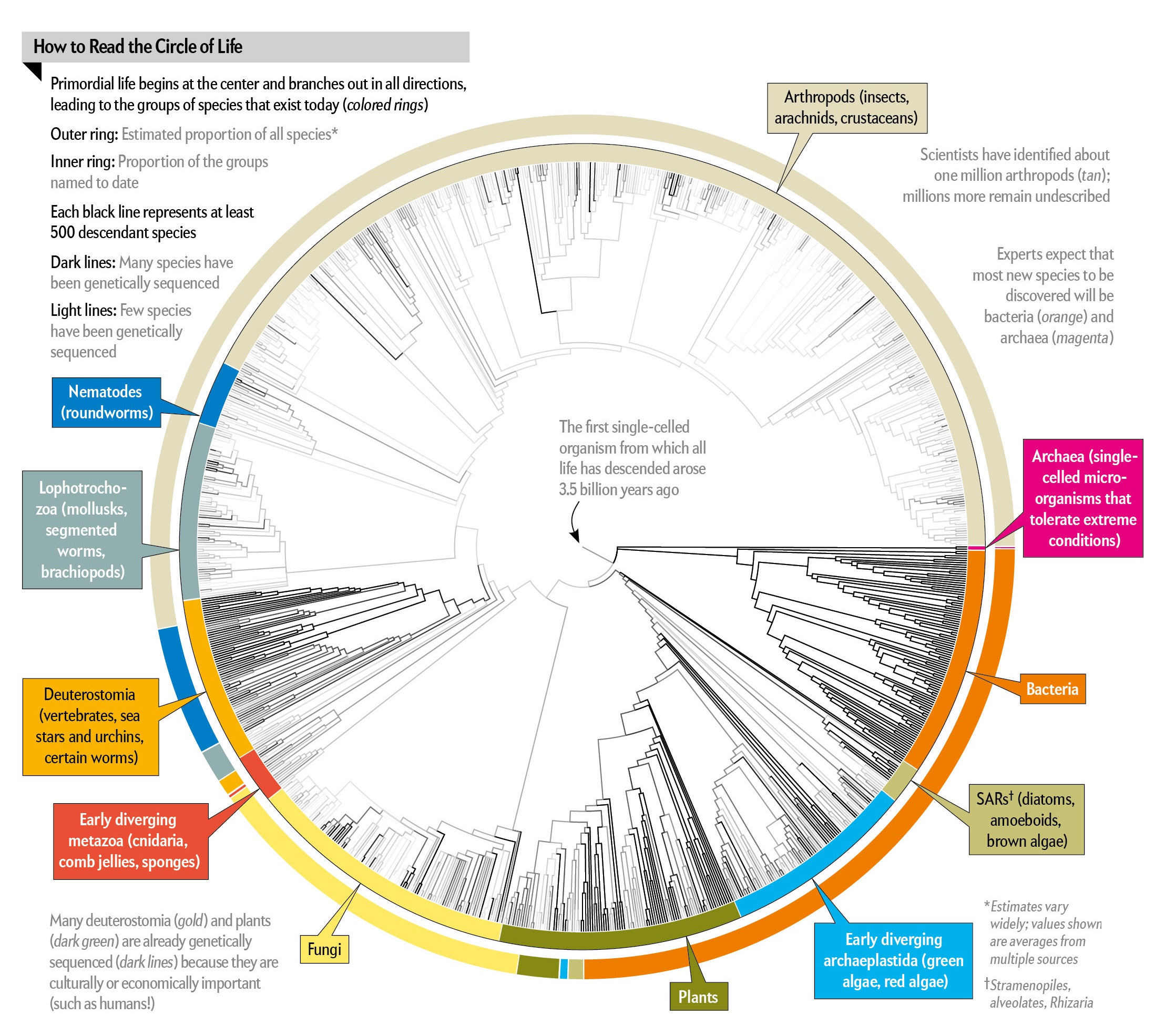

"LIFE ON EARTH IS ONE BIG EXTENDED FAMILY!" is the greatest lesson from evolution, Leonard Eisenberg shouts at the top of his website

https://www.evogeneao.com/en, which he says stands for Evolutionary Genealogy.

Eisenberg created the graphic below to counter the creationist themes he's seen spring into science classes recently. A Penn State University poll in 2011 found 59% of teachers are wary of discussing evolution in the classroom and fear sparking controversy by teaching it. Even more worrying, another 13% dismiss it all together and instead teach intelligent design or creationism in class.

"I run into this even when teaching about Earth history, how life and the planet have changed through time," Eisenberg told Business Insider in an email.

"By emphasizing the 'family' aspect of evolution, in a fun way with attractive art, EvoGeneao makes evolution less scary, more 'family' friendly, and easier for students to understand and teachers to teach."

So what does the family tree of all living things on Earth look like in one graphic? Check it out (Or for a larger version click here):

The age of the Earth radiates out in both directions from the center of the half-circle. As the world gets older, you can see more and more species populate it. The majority of the species on this graphic are still living — except for a few, like the dinosaurs, which are mentioned specifically to point out the five mass extinctions that have changed Earth's history. The graphic didn't include the millions of organisms that have died out over the Earth's history.

"This Great Tree of Life diagram is based primarily on the evolutionary relationships so wonderfully related in Dr. Richard Dawkins' 'The Ancestor's Tale,'" Eisenburg writes on the site. It is meant "to illustrate a great lesson of evolution; that we are related not only to every living thing, but also to every thing that has ever lived."

The lines show different big events — like major extinctions — that have changed Earth's evolutionary history. You can also see the huge explosion of new species at the Cambrian Explosion, 542 million years ago, as the large swath of pink organisms called protosomes.

And we are just a tiny slice of that evolution. Mammals, like humans, are the darkest brown. Here you can see humans as one tiny sliver of life at the end of the evolutionary rainbow:

|

| evo mammals. All of humanity. One little line | Leonard Eisemberg, Evogeneao.com |

And even though humans take up a tiny amount of space on the tree, our presence should be even smaller, Eisenberg says. Bacteria, as you can see, take up a huge swath of life on Earth — as they have from the very beginning, through five mass extinctions:

|

| evo bacteria | Leonard Eisemberg, Evogeneao.com |

As Eisenberg writes on the site:

This Tree of Life is drawn from the human, mammalian point of view. That is why humankind, instead of some other organism, occupies a branch tip at the end of the tree, and why our vertebrate cousins (animals with a backbone) occupy a large part of the tree. This falsely suggests that humans are the ultimate goal of evolution. In fact, if that asteroid or comet that hit the earth 65 million years ago and helped wipe out the dinosaurs, had instead missed the Earth, there might not be a dominant, tool-using, space-faring species on earth. Or if one evolved, it might be a dinosaur, not a mammal.

There are a few other simplifications in the poster, as noted on the site.

As a retired oil industry geologist, Eisenberg says this project developed out of volunteering with his children's schools, pursuing multiple evolution and Earth history based projects to educate the children.

"I needed a diagram to explain evolution for an interpretive sign. I couldn't find any I liked, (mainly because they were not tied to a geologic time scale) so created my own, hand drawn in Photoshop, using available texts and websites," which wasn't an easy feat, Eisenberg said. It "took about six months and many hundreds of hours to find ages of common ancestors."

Eisenberg is currently working on an animated, interactive version of the tree of life for the website.

See the entire graphic over at

EvoGeneao. You can also buy the graphic as a giant laminated poster.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

CIRCLES OF LIFE

Process Evolution:

"How everything relates to everything else"

- re slater

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

OPENTREEOFLIFE.ORG

Sep. 21, 2015

Want to know how related you are to a wombat? Or an amoeba? Now you can, thanks to the newly released

Open Tree of Life, which knits together more than 500 family trees of various groups of organisms to create a supertree with 2.3 million species.

Researchers have already begun to put these new data to work toward a better understanding of life on Earth. “Everything we study in biology can be pinned somewhere on the tree of life,” says James Rosindell, a computational biologist at Imperial College, London, who was not involved with the database. “It’s highly significant that scientists have finally produced a complete tree.”

Over the past 3 years, about 35 people from 11 U.S. labs have spent about 100,000 hours scouring the scientific literature for family trees. They had to resolve naming issues—sometimes a species would have multiple names, and at one point a spiny anteater shared the same moniker with a moray eel, confusing the computers. “There is no single database of accepted names, so the group had to come up with one,” says co-author Douglas Soltis, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

He and his colleagues expected that knitting together these different family trees—which often disagreed—would be the hard part. But what stumped them the most was the dearth of digitized data. Of 7500 trees published between 2000 and 2012, only one in six were computerized. Ultimately, the team used about 500 smaller trees to build one large one, says Karen Cranston, an evolutionary biologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who helped coordinate the effort. With this relatively small sample size, the

draft tree, released online this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “does not summarize what we know,” Cranston says.

But the tree’s website includes links to the original studies examined that offer alternate views, she adds. Furthermore, the site is built to accept feedback and incorporate new data that will eventually be used to update the tree. “We hope the tree looks much different a year from now,” Cranston adds.

Meanwhile, Rosindell and Yan Wong, an evolutionary biologist at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, have adapted a computer tool they’ve been developing to help people “see” the tree. Called OneZoom, the project works like Google Maps in that a user can drill down the tree’s trunks, branches, and tips to see ever finer details. In this

video,

OneZoom starts out with an overview of the tree, then zooms in on successively more detailed branches that lead first to animals, then to placental bearing mammals, and finally to humans. For this tree, Wong used not only the Open Tree data, but also data from other studies he identified as important.

“It’s one cool visualization,” says Open Tree of Life coordinator and evolutionary biologist Stephen Smith from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He hopes there will be many more adaptations of the data. If you could combine it with other data, for example, “you can make your own tree of life.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

Jeremy England, a 31-year-old physicist at MIT, thinks he has

found the underlying physics driving the origin and evolution

of life. | Katherine Taylor for Quanta Magazine

|

This Physicist Has A Groundbreaking Idea

About Why Life Exists

by Natalie Wolchover, Quanta Magazine

December 8, 2014

Why does life exist?

Popular hypotheses credit a primordial soup, a bolt of lightning, and a colossal stroke of luck.

But if a provocative new theory is correct, luck may have little to do with it. Instead, according to the physicist proposing the idea, the origin and subsequent evolution of life follow from the fundamental laws of nature and “should be as unsurprising as rocks rolling downhill.”

From the standpoint of physics, there is one essential difference between living things and inanimate clumps of carbon atoms: The former tend to be much better at capturing energy from their environment and dissipating that energy as heat.

Jeremy England, a 31-year-old assistant professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has derived a mathematical formula that he believes explains this capacity. The formula, based on established physics, indicates that when a group of atoms is driven by an external source of energy (like the sun or chemical fuel) and surrounded by a heat bath (like the ocean or atmosphere), it will often gradually restructure itself in order to dissipate increasingly more energy. This could mean that under certain conditions, matter inexorably acquires the key physical attribute associated with life.

|

Cells from the moss Plagiomnium affine with visible

chloroplasts, organelles that conduct photosynthesis by

capturing sunlight. | Kristian Peters

|

“You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant,” England said.

England’s theory is meant to underlie, rather than replace, Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, which provides a powerful description of life at the level of genes and populations. “I am certainly not saying that Darwinian ideas are wrong,” he explained. “On the contrary, I am just saying that from the perspective of the physics, you might call Darwinian evolution a special case of a more general phenomenon.”

His idea, detailed in a paper and further elaborated in a talk he is delivering at universities around the world, has sparked controversy among his colleagues, who see it as either tenuous or a potential breakthrough, or both.

England has taken “a very brave and very important step,” said Alexander Grosberg, a professor of physics at New York University who has followed England’s work since its early stages. The “big hope” is that he has identified the underlying physical principle driving the origin and evolution of life, Grosberg said.

“Jeremy is just about the brightest young scientist I ever came across,” said Attila Szabo, a biophysicist in the Laboratory of Chemical Physics at the National Institutes of Health who corresponded with England about his theory after meeting him at a conference. “I was struck by the originality of the ideas.”

Others, such as Eugene Shakhnovich, a professor of chemistry, chemical biology and biophysics at Harvard University, are not convinced. “Jeremy’s ideas are interesting and potentially promising, but at this point are extremely speculative, especially as applied to life phenomena,” Shakhnovich said.

England’s theoretical results are generally considered valid. It is his interpretation — that his formula represents the driving force behind a class of phenomena in nature that includes life — that remains unproven. But already, there are ideas about how to test that interpretation in the lab.

“He’s trying something radically different,” said Mara Prentiss, a professor of physics at Harvard who is contemplating such an experiment after learning about England’s work. “As an organizing lens, I think he has a fabulous idea. Right or wrong, it’s going to be very much worth the investigation.”

|

A computer simulation by Jeremy England and colleagues shows

a system of particles confined inside a viscous fluid in which the

turquoise particles are driven by an oscillating force. Over time

(from top to bottom), the force triggers the formation of more

bonds among the particles. | Courtesy of Jeremy England

|

At the heart of England’s idea is the second law of thermodynamics, also known as the law of increasing entropy or the “arrow of time.” Hot things cool down, gas diffuses through air, eggs scramble but never spontaneously unscramble; in short, energy tends to disperse or spread out as time progresses. Entropy is a measure of this tendency, quantifying how dispersed the energy is among the particles in a system, and how diffuse those particles are throughout space. It increases as a simple matter of probability: There are more ways for energy to be spread out than for it to be concentrated.

Thus, as particles in a system move around and interact, they will, through sheer chance, tend to adopt configurations in which the energy is spread out. Eventually, the system arrives at a state of maximum entropy called “thermodynamic equilibrium,” in which energy is uniformly distributed. A cup of coffee and the room it sits in become the same temperature, for example.

As long as the cup and the room are left alone, this process is irreversible. The coffee never spontaneously heats up again because the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against so much of the room’s energy randomly concentrating in its atoms.

Although entropy must increase over time in an isolated or “closed” system, an “open” system can keep its entropy low — that is, divide energy unevenly among its atoms — by greatly increasing the entropy of its surroundings.

In his influential 1944 monograph “What Is Life?” the eminent quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger argued that this is what living things must do. A plant, for example, absorbs extremely energetic sunlight, uses it to build sugars, and ejects infrared light, a much less concentrated form of energy. The overall entropy of the universe increases during photosynthesis as the sunlight dissipates, even as the plant prevents itself from decaying by maintaining an orderly internal structure.

Life does not violate the second law of thermodynamics, but until recently, physicists were unable to use thermodynamics to explain why it should arise in the first place. In Schrödinger’s day, they could solve the equations of thermodynamics only for closed systems in equilibrium. In the 1960s, the Belgian physicist Ilya Prigogine made progress on predicting the behavior of open systems weakly driven by external energy sources (for which he won the 1977 Nobel Prize in chemistry). But the behavior of systems that are far from equilibrium, which are connected to the outside environment and strongly driven by external sources of energy, could not be predicted.

This situation changed in the late 1990s, due primarily to the work of Chris Jarzynski, now at the University of Maryland, and Gavin Crooks, now at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Jarzynski and Crooks showed that the entropy produced by a thermodynamic process, such as the cooling of a cup of coffee, corresponds to a simple ratio: the probability that the atoms will undergo that process divided by their probability of undergoing the reverse process (that is, spontaneously interacting in such a way that the coffee warms up). As entropy production increases, so does this ratio: A system’s behavior becomes more and more “irreversible.” The simple yet rigorous formula could in principle be applied to any thermodynamic process, no matter how fast or far from equilibrium. “Our understanding of far-from-equilibrium statistical mechanics greatly improved,” Grosberg said. England, who is trained in both biochemistry and physics, started his own lab at MIT two years ago and decided to apply the new knowledge of statistical physics to biology.

Using Jarzynski and Crooks’ formulation, he derived a generalization of the second law of thermodynamics that holds for systems of particles with certain characteristics: The systems are strongly driven by an external energy source such as an electromagnetic wave, and they can dump heat into a surrounding bath. This class of systems includes all living things. England then determined how such systems tend to evolve over time as they increase their irreversibility. “We can show very simply from the formula that the more likely evolutionary outcomes are going to be the ones that absorbed and dissipated more energy from the environment’s external drives on the way to getting there,” he said. The finding makes intuitive sense: Particles tend to dissipate more energy when they resonate with a driving force, or move in the direction it is pushing them, and they are more likely to move in that direction than any other at any given moment.

“This means clumps of atoms surrounded by a bath at some temperature, like the atmosphere or the ocean, should tend over time to arrange themselves to resonate better and better with the sources of mechanical, electromagnetic or chemical work in their environments,” England explained.

|

Self-Replicating Sphere Clusters: According to new research at Harvard,

coating the surfaces of microspheres can cause them to spontaneously

assemble into a chosen structure, such as a polytetrahedron (red), which

then triggers nearby spheres into forming an identical structure. | Courtesy

of Michael Brenner/Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

|

Self-replication (or reproduction, in biological terms), the process that drives the evolution of life on Earth, is one such mechanism by which a system might dissipate an increasing amount of energy over time. As England put it, “A great way of dissipating more is to make more copies of yourself.”

In a September paper in the Journal of Chemical Physics, he reported the theoretical minimum amount of dissipation that can occur during the self-replication of RNA molecules and bacterial cells, and showed that it is very close to the actual amounts these systems dissipate when replicating.

He also showed that RNA, the nucleic acid that many scientists believe served as the precursor to DNA-based life, is a particularly cheap building material. Once RNA arose, he argues, its “Darwinian takeover” was perhaps not surprising.

The chemistry of the primordial soup, random mutations, geography, catastrophic events and countless other factors have contributed to the fine details of Earth’s diverse flora and fauna. But according to England’s theory, the underlying principle driving the whole process is dissipation-driven adaptation of matter.

This principle would apply to inanimate matter as well. “It is very tempting to speculate about what phenomena in nature we can now fit under this big tent of dissipation-driven adaptive organization,” England said. “Many examples could just be right under our nose, but because we haven’t been looking for them we haven’t noticed them.”

Scientists have already observed self-replication in nonliving systems. According to new research led by Philip Marcus of the University of California, Berkeley, and reported in Physical Review Letters in August, vortices in turbulent fluids spontaneously replicate themselves by drawing energy from shear in the surrounding fluid. And in a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Michael Brenner, a professor of applied mathematics and physics at Harvard, and his collaborators present theoretical models and simulations of microstructures that self-replicate. These clusters of specially coated microspheres dissipate energy by roping nearby spheres into forming identical clusters. “This connects very much to what Jeremy is saying,” Brenner said.

Besides self-replication, greater structural organization is another means by which strongly driven systems ramp up their ability to dissipate energy. A plant, for example, is much better at capturing and routing solar energy through itself than an unstructured heap of carbon atoms. Thus, England argues that under certain conditions, matter will spontaneously self-organize. This tendency could account for the internal order of living things and of many inanimate structures as well. “Snowflakes, sand dunes and turbulent vortices all have in common that they are strikingly patterned structures that emerge in many-particle systems driven by some dissipative process,” he said. Condensation, wind and viscous drag are the relevant processes in these particular cases.

“He is making me think that the distinction between living and nonliving matter is not sharp,” said Carl Franck, a biological physicist at Cornell University, in an email. “I’m particularly impressed by this notion when one considers systems as small as chemical circuits involving a few biomolecules.”

|

If a new theory is correct, the same physics it identifies as responsible

for the origin of living things could explain the formation of many

other patterned structures in nature. Snowflakes, sand dunes and self-

replicating vortices in the protoplanetary disk may all be examples of

dissipation-driven adaptation. | Wilson Bentley

|

England’s bold idea will likely face close scrutiny in the coming years.

He is currently running computer simulations to test his theory that systems of particles adapt their structures to become better at dissipating energy. The next step will be to run experiments on living systems.

Prentiss, who runs an experimental biophysics lab at Harvard, says England’s theory could be tested by comparing cells with different mutations and looking for a correlation between the amount of energy the cells dissipate and their replication rates.

“One has to be careful because any mutation might do many things,” she said. “But if one kept doing many of these experiments on different systems and if [dissipation and replication success] are indeed correlated, that would suggest this is the correct organizing principle.”

Brenner said he hopes to connect England’s theory to his own microsphere constructions and determine whether the theory correctly predicts which self-replication and self-assembly processes can occur — “a fundamental question in science,” he said.

Having an overarching principle of life and evolution would give researchers a broader perspective on the emergence of structure and function in living things, many of the researchers said. “Natural selection doesn’t explain certain characteristics,” said Ard Louis, a biophysicist at Oxford University, in an email. These characteristics include a heritable change to gene expression called methylation, increases in complexity in the absence of natural selection, and certain molecular changes Louis has recently studied.

If England’s approach stands up to more testing, it could further liberate biologists from seeking a Darwinian explanation for every adaptation and allow them to think more generally in terms of dissipation-driven organization.

They might find, for example, that “the reason that an organism shows characteristic X rather than Y may not be because X is more fit than Y, but because physical constraints make it easier for X to evolve than for Y to evolve,” Louis said.

“People often get stuck in thinking about individual problems,” Prentiss said. Whether or not England’s ideas turn out to be exactly right, she said, “thinking more broadly is where many scientific breakthroughs are made.”

Emily Singer contributed reporting.