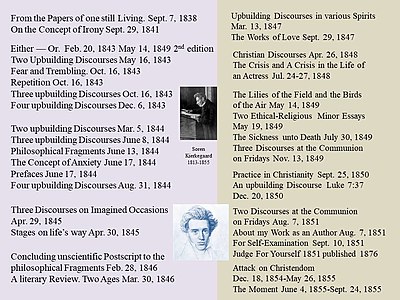

Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard | |

|---|---|

Unfinished sketch of Kierkegaard by his cousin Niels Christian Kierkegaard, c. 1840 | |

| Born | Søren Aabye Kierkegaard 5 May 1813 |

| Died | 11 November 1855 (aged 42) |

| Education | University of Copenhagen (M.A., 1841) |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Thesis | Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt Hensyn til Socrates (On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates) (1841) |

Main interests |

|

Notable ideas |

|

show Influences | |

show Influenced | |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (/ˈsɒrən ˈkɪərkəɡɑːrd/ SORR-ən KEER-kə-gard, US also /-ɡɔːr/ -gor, Danish: [ˈsœːɐ̯n̩ ˈɔˀˌpy ˈkʰiɐ̯kəˌkɒˀ] (listen);[7] 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855[8]) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher.[9][10] He wrote critical texts on organized religion, Christendom, morality, ethics, psychology, and the philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony, and parables. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a "single individual", giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment.[11] He was against literary critics who defined idealist intellectuals and philosophers of his time, and thought that Swedenborg,[12] Hegel,[13] Fichte, Schelling, Schlegel, and Hans Christian Andersen were all "understood" far too quickly by "scholars".[14]

Kierkegaard's theological work focuses on Christian ethics, the institution of the Church, the differences between purely objective proofs of Christianity, the infinite qualitative distinction between man and God, and the individual's subjective relationship to the God-Man Jesus the Christ,[15] which came through faith.[16][17] Much of his work deals with Christian love. He was extremely critical of the practice of Christianity as a state religion, primarily that of the Church of Denmark. His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices.[2]

Kierkegaard's early work was written under the various pseudonyms to present distinctive viewpoints that interact in complex dialogue.[18] He explored particularly complex problems from different viewpoints, each under a different pseudonym. He wrote many Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the "single individual" who might want to discover the meaning of his works. Notably, he wrote: "Science[19] and scholarship want to teach that becoming objective is the way. Christianity teaches that the way is to become subjective, to become a subject."[20] While scientists can learn about the world by observation, Kierkegaard emphatically denied that observation alone could reveal the inner workings of the world of the spirit.[21]

Some of Kierkegaard's key ideas include the concept of "subjective and objective truths", the knight of faith, the recollection and repetition dichotomy, angst, the infinite qualitative distinction, faith as a passion, and the three stages on life's way. Kierkegaard wrote in Danish and the reception of his work was initially limited to Scandinavia, but by the turn of the 20th century his writings were translated into French, German, and other major European languages. By the mid-20th century, his thought exerted a substantial influence on philosophy,[22] theology,[23] and Western culture.[24]

Early years (1813–1836)

Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, had served as a maid in the household before marrying his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. She was an unassuming figure: quiet, and not formally educated. Her granddaughter, Henriette Lund, wrote that she "wielded the sceptre with joy and protected [Søren and Peter] like a hen protecting her chicks".[25] She also wielded influence on her children so that later Peter said that his brother preserved many of their mother's words in his writings.[26] His father, on the other hand, was a well-to-do wool merchant from Jutland.[26] He was a "very stern man, to all appearances dry and prosaic, but under his 'rustic cloak' demeanor he concealed an active imagination which not even his great age could blunt".[27] He was also interested in philosophy and often hosted intellectuals at his home.[28] The young Kierkegaard read the philosophy of Christian Wolff.[29] Kierkegaard, who followed his father's beliefs as a child, was heavily influenced by Michael's devotion to Wolffian rationalism, which caused his father to retire partly to pursue more of Wolff's writings.[30] He also preferred the comedies of Ludvig Holberg,[31] the writings of Johann Georg Hamann,[32] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing,[33] Edward Young,[34] and Plato. The figure of Socrates, who Kierkegaard encountered in Plato's dialogues, would prove to be a phenomenal influence on the philosopher's later interest in irony, as well as his frequent deployment of indirect communication.

Copenhagen in the 1830s and 1840s had crooked streets where carriages rarely went. Kierkegaard loved to walk them. In 1848, Kierkegaard wrote, "I had real Christian satisfaction in the thought that, if there were no other, there was definitely one man in Copenhagen whom every poor person could freely accost and converse with on the street; that, if there were no other, there was one man who, whatever the society he most commonly frequented, did not shun contact with the poor, but greeted every maidservant he was acquainted with, every manservant, every common laborer."[35] Our Lady's Church was at one end of the city, where Bishop Mynster preached the Gospel. At the other end was the Royal Theatre where Fru Heiberg performed.[36]

Based on a speculative interpretation of anecdotes in Kierkegaard's unpublished journals, especially a rough draft of a story called "The Great Earthquake",[37] some early Kierkegaard scholars argued that Michael believed he had earned God's wrath and that none of his children would outlive him. He is said to have believed that his personal sins, perhaps indiscretions such as cursing the name of God in his youth[28] or impregnating Ane out of wedlock, necessitated this punishment. Though five of his seven children died before he did, both Kierkegaard and his brother Peter Christian Kierkegaard outlived him.[38] Peter, who was seven years Kierkegaard's elder, later became bishop in Aalborg.[38] Julia Watkin thought Michael's early interest in the Moravian Church could have led him to a deep sense of the devastating effects of sin.[39]

Kierkegaard came to hope that no one would retain their sins even though they have been forgiven. And by the same token that no one who truly believed in the forgiveness of sin would live their own life as an objection against the existence of forgiveness.[40] He made the point that Cato committed suicide before Caesar had a chance to forgive him. This fear of not finding forgiveness is devastating.[41][42] Edna H. Hong quoted Kierkegaard in her 1984 book, Forgiveness is a Work As Well As a Grace and Kierkegaard wrote about forgiveness in 1847.[43][44][45] In 1954, Samuel Barber set to music Kierkegaard's prayer, "Father in Heaven! Hold not our sins up against us but hold us up against our sins so that the thought of You when it wakens in our soul, and each time it wakens, should not remind us of what we have committed but of what You did forgive, not of how we went astray but of how You did save us!"

From 1821 to 1830 Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue, Østre Borgerdyd Gymnasium when the school was situated in Klarebodeme, where he studied Latin and history among other subjects. During his time there he was described as "very conservative"; someone who would "honour the King, love the church and respect the police".[46] He frequently got into altercations with fellow students and was ambivalent towards his teachers.[46] He went on to study theology at the University of Copenhagen. He had little interest in historical works, philosophy dissatisfied him, and he couldn't see "dedicating himself to Speculation".[47] He said, "What I really need to do is to get clear about "what am I to do", not what I must know." He wanted to "lead a completely human life and not merely one of knowledge".[48] Kierkegaard didn't want to be a philosopher in the traditional or Hegelian sense[49] and he didn't want to preach a Christianity that was an illusion.[50] "But he had learned from his father that one can do what one wills, and his father's life had not discredited this theory."[51]

One of the first physical descriptions of Kierkegaard comes from an attendee, Hans Brøchner, at his brother Peter's wedding party in 1836: "I found [his appearance] almost comical. He was then twenty-three years old; he had something quite irregular in his entire form and had a strange coiffure. His hair rose almost six inches above his forehead into a tousled crest that gave him a strange, bewildered look."[52] Another comes from Kierkegaard's niece, Henriette Lund (1829–1909). When Søren Kierkegaard was a little boy he "was of slender and delicate appearance, and ran about in a little coat of red-cabbage color. He used to be called 'fork' by his father, because of his tendency, developed quite early, toward satirical remarks. Although a serious, almost austere tone pervaded the Kierkegaards' house, I have the firm impression that there was a place for youthful vivacity too, even though of a more sedate and home-made kind than one is used to nowadays. The house was open for an 'old-fashioned hospitality'" he was also described "quaintly attired, slight and small".[53][46]

Kierkegaard's mother "was a nice little woman with an even and happy disposition," according to a grandchild's description. She was never mentioned in Kierkegaard's works. Ane died on 31 July 1834, age 66, possibly from typhus.[54] His father died on 8 August 1838, age 82. On 11 August, Kierkegaard wrote: "My father died on Wednesday (the 8th) at 2:00 a.m. I so deeply desired that he might have lived a few years more... Right now I feel there is only one person (E. Boesen) with whom I can really talk about him. He was a 'faithful friend.'"[55] Troels Frederik Lund, his nephew, was instrumental in providing biographers with much information regarding Søren Kierkegaard. Lund was a good friend of Georg Brandes and Julius Lange.[56] Here is an anecdote about his father from Kierkegaard's journals.

Journals

According to Samuel Hugo Bergmann, "Kierkegaard's journals are one of the most important sources for an understanding of his philosophy".[57] Kierkegaard wrote over 7,000 pages in his journals on events, musings, thoughts about his works and everyday remarks.[58] The entire collection of Danish journals (Journalen) was edited and published in 13 volumes consisting of 25 separate bindings including indices. The first English edition of the journals was edited by Alexander Dru in 1938.[59] The style is "literary and poetic [in] manner".[60]

Kierkegaard wanted to have Regine, his fiancée (see below), as his confidant but considered it an impossibility for that to happen so he left it to "my reader, that single individual" to become his confidant. His question was whether or not one can have a spiritual confidant. He wrote the following in his Concluding Postscript: "With regard to the essential truth, a direct relation between spirit and spirit is unthinkable. If such a relation is assumed, it actually means that the party has ceased to be spirit."[61]

Kierkegaard's journals were the source of many aphorisms credited to the philosopher. The following passage, from 1 August 1835, is perhaps his most oft-quoted aphorism and a key quote for existentialist studies:

He wrote this way about indirect communication in the same journal entry.

Although his journals clarify some aspects of his work and life, Kierkegaard took care not to reveal too much. Abrupt changes in thought, repetitive writing, and unusual turns of phrase are some among the many tactics he used to throw readers off track. Consequently, there are many varying interpretations of his journals. Kierkegaard did not doubt the importance his journals would have in the future. In December 1849, he wrote:

"Were I to die now the effect of my life would be exceptional; much of what I have simply jotted down carelessly in the Journals would become of great importance and have a great effect; for then people would have grown reconciled to me and would be able to grant me what was, and is, my right."[62]

Regine Olsen and graduation (1837–1841)

An important aspect of Kierkegaard's life – generally considered to have had a major influence on his work – was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen (1822–1904). Kierkegaard and Olsen met on 8 May 1837 and were instantly attracted to each other, but sometime around 11 August 1838 he had second thoughts. In his journals, Kierkegaard wrote idealistically about his love for her.[63]

On 8 September 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Olsen. He soon felt disillusioned about his prospects. He broke off the engagement on 11 August 1841, though it is generally believed that the two were deeply in love. In his journals, Kierkegaard mentions his belief that his "melancholy" made him unsuitable for marriage, but his precise motive for ending the engagement remains unclear.[38][64][65][66][67] Later on, he wrote:

"I owe everything to the wisdom of an old man and to the simplicity of a young girl."[68] The old man in this statement is said to be his father while Olsen was the girl.[28] Martin Buber said "Kierkegaard does not marry in defiance of the whole nineteenth century".[69]

Kierkegaard then turned his attention to his examinations. On 13 May 1839, he wrote, "I have no alternative than to suppose that it is God's will that I prepare for my examination and that it is more pleasing to Him that I do this than actually coming to some clearer perception by immersing myself in one or another sort of research, for obedience is more precious to him than the fat of rams."[70] The death of his father and the death of Poul Møller also played a part in his decision.

On 29 September 1841, Kierkegaard wrote and defended his master's thesis, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates. The university panel considered it noteworthy and thoughtful, but too informal and witty for a serious academic thesis.[71] The thesis dealt with irony and Schelling's 1841 lectures, which Kierkegaard had attended with Mikhail Bakunin, Jacob Burckhardt, and Friedrich Engels; each had come away with a different perspective.[72] Kierkegaard graduated from university on 20 October 1841 with a Magister Artium (Master of Arts). His family's inheritance of approximately 31,000 rigsdaler[59] enabled him to fund his work and living expenses including servants. [*approx 3.1 million in 1841 - re slater]

Authorship (1843–1846)Kierkegaard published some of his works using pseudonyms and for others he signed his own name as author. Whether being published under pseudonym or not, Kierkegaard's central writing on religion was Fear and Trembling, and Either/Or is considered to be his magnum opus. Pseudonyms were used often in the early 19th century as a means of representing viewpoints other than the author's own. Kierkegaard employed the same technique as a way to provide examples of indirect communication. In writing under various pseudonyms to express sometimes contradictory positions, Kierkegaard is sometimes criticized for playing with various viewpoints without ever committing to one in particular. He has been described by those opposing his writings as indeterminate in his standpoint as a writer, though he himself has testified to all his work deriving from a service to Christianity.[73] After On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, his 1841 master's thesis under Frederik Christian Sibbern,[74] he wrote his first book under the pseudonym "Johannes Climacus" (after John Climacus) between 1841 and 1842. De omnibus dubitandum est (Latin: "Everything must be doubted") was not published until after his death.[75]

[*Soren wrote under pseudonyms purposely to offer readers conflicted readings of social and church ethics in order for the reader to be spiritually tested to determine in their own mind and heart whether truth was truth-truth or comprised-truth in light of Christ and his redemptive work. - re slater]

Kierkegaard's magnum opus Either/Or was published 20 February 1843; it was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling's Philosophy of Revelation. Either/Or includes essays of literary and music criticism and a set of romantic-like-aphorisms, as part of his larger theme of examining the reflective and philosophical structure of faith.[76][77] Edited by "Victor Eremita", the book contained the papers of an unknown "A" and "B" which the pseudonymous author claimed to have discovered in a secret drawer of his secretary.[78] Eremita had a hard time putting the papers of "A" in order because they were not straightforward. "B"'s papers were arranged in an orderly fashion.[79] Both of these characters are trying to become religious individuals.[80] Each approached the idea of first love from an esthetic and an ethical point of view. The book is basically an argument about faith and marriage with a short discourse at the end telling them they should stop arguing. Eremita thinks "B", a judge, makes the most sense. Kierkegaard stressed the "how" of Christianity as well as the "how" of book reading in his works rather than the "what".[81]

Three months after the publication of Either/Or, 16 May 1843, he published Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 and continued to publish discourses along with his pseudonymous books. These discourses were published under Kierkegaard's own name and are available as Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses today. David F. Swenson first translated the works in the 1940s and titled them the Edifying Discourses; however, in 1990, Howard V. and Edna H. Hong translated the works again but called them the Upbuilding Discourses. The word "upbuilding" was more in line with Kierkegaard's thought after 1846, when he wrote Christian deliberations[82] about Works of Love.[83] An upbuilding discourse or edifying discourse isn't the same as a sermon because a sermon is preached to a congregation while a discourse can be carried on between several people or even with oneself. The discourse or conversation should be "upbuilding", which means one would build up the other person, or oneself, rather than tear down to build up. Kierkegaard said:

"Although this little book (which is called "discourses," not sermons, because its author does not have authority to preach, "upbuilding discourses," not discourses for upbuilding, because the speaker by no means claims to be a teacher) wishes to be only what it is, a superfluity, and desires only to remain in hiding".[84]

On 16 October 1843, Kierkegaard published three more books about love and faith and several more discourses. Fear and Trembling was published under the pseudonym Johannes de Silentio. Repetition is about a Young Man (Søren Kierkegaard) who has anxiety and depression because he feels he has to sacrifice his love for a girl (Regine Olsen) to God. He tries to see if the new science of psychology can help him understand himself. Constantin Constantius, who is the pseudonymous author of that book, is the psychologist. At the same time, he published Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 under his own name, which dealt specifically with how love can be used to hide things from yourself or others.[85] These three books, all published on the same day, are an example of Kierkegaard's method of indirect communication.

Kierkegaard questioned whether an individual can know if something is a good gift from God or not and concludes by saying, "it does not depend, then, merely upon what one sees, but what one sees depends upon how one sees; all observation is not just a receiving, a discovering, but also a bringing forth, and insofar as it is that, how the observer himself is constituted is indeed decisive."[86] God's love is imparted indirectly just as our own sometimes is.[87]

During 1844, he published two, three, and four more upbuilding discourses just as he did in 1843, but here he discussed how an individual might come to know God. Theologians, philosophers and historians were all engaged in debating about the existence of God. This is direct communication and Kierkegaard thinks this might be useful for theologians, philosophers, and historians (associations) but not at all useful for the "single individual" who is interested in becoming a Christian. Kierkegaard always wrote for "that single individual whom I with joy and gratitude call my reader"[88] The single individual must put what is understood to use or it will be lost. Reflection can take an individual only so far before the imagination begins to change the whole content of what was being thought about. Love is won by being exercised just as much as faith and patience are.

He also wrote several more pseudonymous books in 1844: Philosophical Fragments, Prefaces and The Concept of Anxiety and finished the year up with Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844. He used indirect communication in the first book and direct communication in the rest of them. He doesn't believe the question about God's existence should be an opinion held by one group and differently by another no matter how many demonstrations are made. He says it's up to the single individual to make the fruit of the Holy Spirit real because love and joy are always just possibilities. Christendom wanted to define God's attributes once and for all but Kierkegaard was against this. His love for Regine was a disaster but it helped him because of his point of view.[89]

Kierkegaard believed "each generation has its own task and need not trouble itself unduly by being everything to previous and succeeding generations".[90] In an earlier book he had said,

"to a certain degree every generation and every individual begins his life from the beginning",[91] and in another, "no generation has learned to love from another, no generation is able to begin at any other point than the beginning", "no generation learns the essentially human from a previous one."[92]

And, finally, in 1850 he wrote,

"those true Christians who in every generation live a life contemporaneous with that of Christ have nothing whatsoever to do with Christians of the preceding generation, but all the more with their contemporary, Christ. His life here on earth attends every generation, and every generation severally, as Sacred History..."[93] But in 1848, "The whole generation and every individual in the generation is a participant in one’s having faith."[94]

He was against the Hegelian idea of mediation[95][96] because it introduces a

"third term"[97] that comes between the single individual and the object of desire. Kierkegaard wrote in 1844, 'If a person can be assured of the grace of God without needing temporal evidence as a middleman or as the dispensation advantageous to him as interpreter, then it is indeed obvious to him that the grace of God is the most glorious of all."[98]

He was against mediation and settled instead on the choice to be content with the grace of God or not. It's the choice between the possibility of the "temporal and the eternal", "mistrust and belief, and deception and truth",[99] "subjective and objective".[100] These are the "magnitudes" of choice. He always stressed deliberation and choice in his writings and wrote against comparison.[101] This is how Kant put it in 1786 and Kierkegaard put it in 1847:

The inwardness of Christianity

[Truth as Subjective - e.g., truth as subjectively acquired and changing of the indiviual; truth must be met by the person without which the individual cannot be affected by truth. - re slater]

Kierkegaard believed God comes to each individual mysteriously.[102][103] He published Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (first called Thoughts on Crucial Situations in Human Life, in David F. Swenson's 1941 translation) under his own name on 29 April, and Stages on Life's Way edited by Hilarius Bookbinder, 30 April 1845. The Stages is a sequel to Either/Or which Kierkegaard did not think had been adequately read by the public and in Stages he predicted "that two-thirds of the book's readers will quit before they are halfway through, out of boredom they will throw the book away."[104] He knew he was writing books but had no idea who was reading them. His sales were meager and he had no publicist or editor. He was writing in the dark, so to speak.[105] Many of his readers have been and continue to be in the dark about his intentions. He explained himself in his "Journal": "What I have understood as the task of the authorship has been done. It is one idea, this continuity from Either/Or to Anti-Climacus, the idea of religiousness in reflection. The task has occupied me totally, for it has occupied me religiously; I have understood the completion of this authorship as my duty, as a responsibility resting upon me." He advised his reader to read his books slowly and also to read them aloud since that might aid in understanding.[106]

He used indirect communication in his writings by, for instance, referring to the religious person as the “knight of hidden inwardness” in which he’s different from everyone else, even though he looks like everyone else, because everything is hidden within him.[107] He put it this way in 1847: “You are indistinguishable from anyone else among those whom you might wish to resemble, those who in the decision are with the good-they are all clothed alike, girdled about the loins with truth, clad in the armor of righteousness, wearing the helmet of salvation!" [108][109]

Kierkegaard was aware of the hidden depths inside of each single individual. The hidden inwardness is inventive in deceiving or evading others. Much of it is afraid of being seen and entirely disclosed. “Therefore all calm and, in the intellectual sense, dispassionate observers, who eminently know how to delve searchingly and penetratingly into the inner being, these very people judge with such infinite caution or refrain from it entirely because, enriched by observation, they have a developed conception of the enigmatic world of the hidden, and because as observers they have learned to rule over their passions. Only superficial, impetuous passionate people, who do not understand themselves and for that reason naturally are unaware that they do not know others, judge precipitously. Those with insight, those who know never do this.”[110]

Kierkegaard imagined hidden inwardness several ways in 1848.

He was writing about the subjective inward nature of God's encounter with the individual in many of his books, and his goal was to get the single individual away from all the speculation that was going on about God and Christ. Speculation creates quantities of ways to find God and his Goods but finding faith in Christ and putting the understanding to use stops all speculation, because then one begins to actually exist as a Christian, or in an ethical/religious way. He was against an individual waiting until certain of God's love and salvation before beginning to try to become a Christian. He defined this as a "special type of religious conflict the Germans call Anfechtung" (contesting or disputing).[111][112]

In Kierkegaard's view the Church should not try to prove Christianity or even defend it. It should help the single individual to make a leap of faith, the faith that God is love and has a task for that very same single individual.[113] He wrote the following about fear and trembling and love as early as 1839, "Fear and trembling is not the primus motor in the Christian life, for it is love; but it is what the oscillating balance wheel is to the clock-it is the oscillating balance wheel of the Christian life.[114] Kierkegaard identified the leap of faith as the good resolution.[115] Kierkegaard discussed the knight of faith in Works of Love, 1847 by using the story of Jesus healing the bleeding woman who showed the " originality of faith" by believing that if she touched Jesus' robe she would be healed. She kept that secret within herself.[116]

Kierkegaard wrote his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments in 1846 and here he tried to explain the intent of the first part of his authorship.[117][118] He said, "Christianity will not be content to be an evolution within the total category of human nature; an engagement such as that is too little to offer to a god. Neither does it even want to be the paradox for the believer, and then surreptitiously, little by little, provide him with understanding, because the martyrdom of faith (to crucify one's understanding) is not a martyrdom of the moment, but the martyrdom of continuance."[119][120] The second part of his authorship was summed up in Practice in Christianity:

Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno and Thomas Henry Croxall, argue that the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views.[122] This view leads to confusions and contradictions which make Kierkegaard appear philosophically incoherent.[123] Later scholars, such as the post-structuralists, interpreted Kierkegaard's work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors.[124] Postmodern Christians present a different interpretation of Kierkegaard's works.[125] Kierkegaard used the category of "The Individual"[126] to stop[127] the endless Either/Or.[128]

Pseudonyms

Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms,[129] in chronological order, were:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or

- A, writer of many articles in Either/Or

- Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either/Or

- Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Constantine Constantius, author of the first half of Repetition

- Young Man, author of the second half of Repetition

- Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Anxiety

- Nicolaus Notabene, author of Prefaces

- Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

- Inter et Inter, author of The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress

- H.H., author of Two Minor Ethical-Religious Essays

- Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness Unto Death and Practice in Christianity

Kierkegaard explained his pseudonyms this way in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript:

All of these writings analyze the concept of faith, on the supposition that if people are confused about faith, as Kierkegaard thought the inhabitants of Christendom were, they will not be in a position to develop the virtue. Faith is a matter of reflection in the sense that one cannot have the virtue unless one has the concept of virtue – or at any rate the concepts that govern faith's understanding of self, world, and God.[130]

The Corsair Affair

On 22 December 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller, who studied at the University of Copenhagen at the same time as Kierkegaard, published an article indirectly criticizing Stages on Life's Way. The article complimented Kierkegaard for his wit and intellect, but questioned whether he would ever be able to master his talent and write coherent, complete works. Møller was also a contributor to and editor of The Corsair, a Danish satirical paper that lampooned everyone of notable standing. Kierkegaard published a sarcastic response, charging that Møller's article was merely an attempt to impress Copenhagen's literary elite.

Kierkegaard wrote two small pieces in response to Møller, The Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action. The former focused on insulting Møller's integrity while the latter was a directed assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard, after criticizing the journalistic quality and reputation of the paper, openly asked The Corsair to satirize him.[131]

Kierkegaard's response earned him the ire of the paper and its second editor, also an intellectual of Kierkegaard's own age, Meïr Aron Goldschmidt.[132] Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his offer to "be abused", and unleashed a series of attacks making fun of Kierkegaard's appearance, voice and habits. For months, Kierkegaard perceived himself to be the victim of harassment on the streets of Denmark. In a journal entry dated 9 March 1846, Kierkegaard made a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explained that this attack made him rethink his strategy of indirect communication.[133]

There had been much discussion in Denmark about the pseudonymous authors until the publication of Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, 27 February 1846, where he openly admitted to be the author of the books because people began wondering if he was, in fact, a Christian or not.[134][135] Several Journal entries from that year shed some light on what Kierkegaard hoped to achieve.[136][137][138][139] This book was published under an earlier pseudonym, Johannes Climacus. On 30 March 1846 he published Two Ages: A Literary Review, under his own name. A critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on what he considered the nature of modernity and its passionless attitude towards life. Kierkegaard writes that "the present age is essentially a sensible age, devoid of passion ... The trend today is in the direction of mathematical equality, so that in all classes about so and so many uniformly make one individual".[140] In this, Kierkegaard attacked the conformity and assimilation of individuals into "the crowd"[141] which became the standard for truth, since it was the numerical. How can one love the neighbor if the neighbor is always regarded as the wealthy or the poor or the lame?[142]

As part of his analysis of the "crowd", Kierkegaard accused newspapers of decay and decadence. Kierkegaard stated Christendom had "lost its way" by recognizing "the crowd", as the many who are moved by newspaper stories, as the court of last resort in relation to "the truth". Truth comes to a single individual, not all people at one and the same time. Just as truth comes to one individual at a time so does love. One doesn't love the crowd but does love their neighbor, who is a single individual. He says, "never have I read in the Holy Scriptures this command: You shall love the crowd; even less: You shall, ethico-religiously, recognize in the crowd the court of last resort in relation to 'the truth.'"[143][144]

Authorship (1847–1855)

Is it really hopelessness to reject the task because it is too heavy; is it really hopelessness almost to collapse under the burden because it is so heavy; is it really hopelessness to give up hope out of fear of the task? Oh no, but this is hopelessness: to will with all one's might-but there is no task. Thus, only if there is nothing to do and if the person who says it were without guilt before God-for if he is guilty, there is indeed always something to do-only if there is nothing to do and this is understood to mean that there is no task, only then is there hopelessness. Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Hong p. 277Kierkegaard began to write again in 1847: the three-part Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits.[64] It included Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, What we Learn from the Lilies in the Field and from the Birds in the Air,[145] and The Gospel of Sufferings. He asked, What does it mean to be a single individual who wants to do the good? What does it mean to be a human being? What does it mean to follow Christ? He now moves from "upbuilding (Edifying) discourses" to "Christian discourses", however, he still maintains that these are not "sermons".[146] A sermon is about struggle with oneself about the tasks life offers one and about repentance for not completing the tasks.[147] Later, in 1849, he wrote devotional discourses and Godly discourses.

Works of Love[148] followed these discourses on (29 September 1847). Both books were authored under his own name. It was written under the themes "Love covers a multitude of sins" and "Love builds up". (1 Peter 4:8 and 1 Corinthians 8:1) Kierkegaard believed that "all human speech, even divine speech of Holy Scripture, about the spiritual is essentially metaphorical speech".[149] "To build up" is a metaphorical expression. One can never be all human or all spirit, one must be both.

Later, in the same book, Kierkegaard deals with the question of sin and forgiveness. He uses the same text he used earlier in Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, Love hides a multitude of sins. (1 Peter 4:8). He asks if "one who tells his neighbors faults hides or increases the multitude of sins".[150]

In 1848 he published Christian Discourses under his own name and The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress under the pseudonym Inter et Inter. Christian Discourses deals the same theme as The Concept of Anxiety, angst. The text is the Gospel of Matthew 6 verses 24–34. This was the same passage he had used in his What We Learn From the Lilies in the Field and From the Birds of the Air of 1847. He wrote:

Kierkegaard tried to explain his prolific use of pseudonyms again in The Point of View of My Work as an Author, his autobiographical explanation for his writing style. The book was finished in 1848, but not published until after his death by his brother Christian Peter Kierkegaard. Walter Lowrie mentioned Kierkegaard's "profound religious experience of Holy Week 1848" as a turning point from "indirect communication" to "direct communication" regarding Christianity.[151] However, Kierkegaard stated that he was a religious author throughout all of his writings and that his aim was to discuss "the problem 'of becoming a Christian', with a direct polemic against the monstrous illusion we call Christendom".[152] He expressed the illusion this way in his 1848 "Christian Address", Thoughts Which Wound From Behind – for Edification.

He wrote three discourses under his own name and one pseudonymous book in 1849. He wrote The Lily in the Field and the Bird of the Air. Three Devotional Discourses, Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays and Two Ethical-Religious Essays. The first thing any child finds in life is the external world of nature. This is where God placed his natural teachers. He's been writing about confession and now openly writes about Holy Communion which is generally preceded by confession. This he began with the confessions of the esthete and the ethicist in Either/Or and the highest good peace in the discourse of that same book. His goal has always been to help people become religious but specifically Christian religious. He summed his position up earlier in his book, The Point of View of My Work as an Author, but this book was not published until 1859.

The second edition of Either/Or was published early in 1849. Later that year he published The Sickness unto Death, under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus. He's against Johannes Climacus, who kept writing books about trying to understand Christianity. Here he says, "Let others admire and praise the person who pretends to comprehend Christianity. I regard it as a plain ethical task – perhaps requiring not a little self-denial in these speculative times, when all 'the others' are busy with comprehending-to admit that one is neither able nor supposed to comprehend it."[155] Sickness unto death was a familiar phrase in Kierkegaard's earlier writings.[156] This sickness is despair and for Kierkegaard despair is a sin. Despair is the impossibility of possibility.[157] Kierkegaard writes:

In Practice in Christianity, 25 September 1850, his last pseudonymous work, he stated, "In this book, originating in the year 1848, the requirement for being a Christian is forced up by the pseudonymous authors to a supreme ideality."[158] This work was called Training in Christianity when Walter Lowrie translated it in 1941.

He now pointedly referred to the acting single individual in his next three publications; For Self-Examination, Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays, and in 1852 Judge for Yourselves!.[159][160] Judge for Yourselves! was published posthumously in 1876. Here is an interesting quote from For Self Examination.

In 1851 Kierkegaard wrote his Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays where he once more discussed sin, forgiveness, and authority using that same verse from 1 Peter 4:8 that he used twice in 1843 with his Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843.

Kierkegaard began his 1843 book Either/Or with a question: "Are passions, then, the pagans of the soul? Reason alone baptized?"[161] He didn't want to devote himself to Thought or Speculation like Hegel did. Faith, hope, love, peace, patience, joy, self-control, vanity, kindness, humility, courage, cowardliness, pride, deceit, and selfishness. These are the inner passions that Thought knows little about. Hegel begins the process of education with Thought but Kierkegaard thinks we could begin with passion, or a balance between the two, a balance between Goethe and Hegel.[162] He was against endless reflection with no passion involved. But at the same time he did not want to draw more attention to the external display of passion but the internal (hidden) passion of the single individual. Kierkegaard clarified this intention in his Journals.[106]

Schelling put Nature first and Hegel put Reason first but Kierkegaard put the human being first and the choice first in his writings. He makes an argument against Nature here and points out that most single individuals begin life as spectators of the visible world and work toward knowledge of the invisible world.

Nikolai Berdyaev makes a related argument against reason in his 1945 book The Divine and the Human.[163][164]

Attack upon the Lutheran State Church

Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Church of Denmark by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment (Øjeblikket), also translated as The Instant. These pamphlets are now included in Kierkegaard's Attack Upon Christendom.[165] The Moment was translated into German and other European languages in 1861 and again in 1896.[166]

Kierkegaard first moved to action after Professor (soon Bishop) Hans Lassen Martensen gave a speech in church in which he called the recently deceased Bishop Jacob Peter Mynster a "truth-witness, one of the authentic truth-witnesses".[16] Kierkegaard explained, in his first article, that Mynster's death permitted him—at last—to be frank about his opinions. He later wrote that all his former output had been "preparations" for this attack, postponed for years waiting for two preconditions: 1) both his father and bishop Mynster should be dead before the attack, and 2) he should himself have acquired a name as a famous theologic writer.[167] Kierkegaard's father had been Mynster's close friend, but Søren had long come to see that Mynster's conception of Christianity was mistaken, demanding too little of its adherents. Kierkegaard strongly objected to the portrayal of Mynster as a 'truth-witness'.

Kierkegaard described the hope the witness to the truth has in 1847 and in his Journals.

Kierkegaard's pamphlets and polemical books, including The Moment, criticized several aspects of church formalities and politics.[168] According to Kierkegaard, the idea of congregations keeps individuals as children since Christians are disinclined from taking the initiative to take responsibility for their own relation to God. He stressed that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual".[169] Furthermore, since the Church was controlled by the State, Kierkegaard believed the State's bureaucratic mission was to increase membership and oversee the welfare of its members. More members would mean more power for the clergymen: a corrupt ideal.[170] This mission would seem at odds with Christianity's true doctrine, which, to Kierkegaard, is to stress the importance of the individual, not the whole.[59] Thus, the state-church political structure is offensive and detrimental to individuals, since anyone can become "Christian" without knowing what it means to be Christian. It is also detrimental to the religion itself since it reduces Christianity to a mere fashionable tradition adhered to by unbelieving "believers", a "herd mentality" of the population, so to speak.[171] Kierkegaard always stressed the importance of the conscience and the use of it.[172] Nonetheless, Kierkegaard has been described as "profoundly Lutheran."[173]

Death

Before the tenth issue of his periodical The Moment could be published, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street. He stayed in the hospital for over a month[174] and refused communion. At that time he regarded pastors as mere political officials, a niche in society who were clearly not representative of the divine. He told Emil Boesen, a friend since childhood, who kept a record of his conversations with Kierkegaard, that his life had been one of immense suffering, which may have seemed like vanity to others, but he did not think it so.[64][175]

Kierkegaard died in Frederiks Hospital after over a month, possibly from complications from a fall from a tree in his youth.[176] It has been suggested by professor Kaare Weismann and literature scientist Jens Staubrand that Kierkegaard died from Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis.[177] He was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen. At Kierkegaard's funeral, his nephew Henrik Lund caused a disturbance by protesting Kierkegaard's burial by the official church. Lund maintained that Kierkegaard would never have approved, had he been alive, as he had broken from and denounced the institution. Lund was later fined for his disruption of a funeral.[38]

Reception

19th-century reception

In September 1850, the Western Literary Messenger wrote: "While Martensen with his wealth of genius casts from his central position light upon every sphere of existence, upon all the phenomena of life, Søren Kierkegaard stands like another Simon Stylites, upon his solitary column, with his eye unchangeably fixed upon one point."[178] In 1855, the Danish National Church published his obituary. Kierkegaard did have an impact there judging from the following quote from their article: "The fatal fruits which Dr. Kierkegaard show to arise from the union of Church and State, have strengthened the scruples of many of the believing laity, who now feel that they can remain no longer in the Church, because thereby they are in communion with unbelievers, for there is no ecclesiastical discipline."[178][179]

Changes did occur in the administration of the Church and these changes were linked to Kierkegaard's writings. The Church noted that dissent was "something foreign to the national mind". On 5 April 1855 the Church enacted new policies: "every member of a congregation is free to attend the ministry of any clergyman, and is not, as formerly, bound to the one whose parishioner he is". In March 1857, compulsory infant baptism was abolished. Debates sprang up over the King's position as the head of the Church and over whether to adopt a constitution. Grundtvig objected to having any written rules. Immediately following this announcement the "agitation occasioned by Kierkegaard" was mentioned. Kierkegaard was accused of Weigelianism and Darbyism, but the article continued to say, "One great truth has been made prominent, viz (namely): That there exists a worldly-minded clergy; that many things in the Church are rotten; that all need daily repentance; that one must never be contented with the existing state of either the Church or her pastors."[178][180]

Hans Martensen was the subject of a Danish article, Dr. S. Kierkegaard against Dr. H. Martensen By Hans Peter Kofoed-Hansen (1813–1893) that was published in 1856[181] (untranslated) and Martensen mentioned him extensively in Christian Ethics, published in 1871.[182] "Kierkegaard's assertion is therefore perfectly justifiable, that with the category of "the individual" the cause of Christianity must stand and fall; that, without this category, Pantheism had conquered unconditionally. From this, at a glance, it may be seen that Kierkegaard ought to have made common cause with those philosophic and theological writers who specially desired to promote the principle of Personality as opposed to Pantheism. This is, however, far from the case. For those views which upheld the category of existence and personality, in opposition to this abstract idealism, did not do this in the sense of an either—or, but in that of a both—and. They strove to establish the unity of existence and idea, which may be specially seen from the fact that they desired system and totality. Martensen accused Kierkegaard and Alexandre Vinet of not giving society its due. He said both of them put the individual above society, and in so doing, above the Church."[178][183] Another early critic was Magnús Eiríksson who criticized Martensen and wanted Kierkegaard as his ally in his fight against speculative theology.

"August Strindberg was influenced by the Danish individualistic philosopher Kierkegaard while a student at Uppsala University (1867–1870) and mentioned him in his book Growth of a Soul as well as Zones of the Spirit (1913).[184][185] Edwin Bjorkman credited Kierkegaard as well as Henry Thomas Buckle and Eduard von Hartmann with shaping Strindberg's artistic form until he was strong enough to stand wholly on his own feet."[186] The dramatist Henrik Ibsen is said to have become interested in Kierkegaard as well as the Norwegian national writer and poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910) who named one of his characters Søren Pedersen in his 1890 book In God's Way. Kierkegaard's father's name was Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard.[187][188]

Several of Kierkegaard's works were translated into German from 1861 onward, including excerpts from Practice in Christianity (1872), from Fear and Trembling[189] and Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1874), Four Upbuilding Discourses and Christian Discourses (1875), and The Lillis of the Field and the Birds of the Air (1876) according to Kierkegaard's International Reception: Northern and Western Europe: Toma I, by John Stewart, see p. 388ff'[190] The Sickness Unto Death, 1881[191] Twelve speeches by Søren Kierkegaard, by Julius Fricke, 1886[192] Stages on Life's Way, 1886 (Bärthold).[193]

Otto Pfleiderer in The Philosophy of Religion: On the Basis of Its History (1887), claimed that Kierkegaard presented an anti-rational view of Christianity. He went on to assert that the ethical side of a human being has to disappear completely in his one-sided view of faith as the highest good. He wrote, "Kierkegaard can only find true Christianity in entire renunciation of the world, in the following of Christ in lowliness and suffering especially when met by hatred and persecution on the part of the world. Hence his passionate polemic against ecclesiastical Christianity, which he says has fallen away from Christ by coming to a peaceful understanding with the world and conforming itself to the world's life. True Christianity, on the contrary, is constant polemical pathos, a battle against reason, nature, and the world; its commandment is enmity with the world; its way of life is the death of the naturally human."[178][194]

An article from an 1889 dictionary of religion revealed a good idea of how Kierkegaard was regarded at that time, stating: "Having never left his native city more than a few days at a time, excepting once, when he went to Germany to study Schelling's philosophy. He was the most original thinker and theological philosopher the North ever produced. His fame has been steadily growing since his death, and he bids fair to become the leading religio-philosophical light of Germany. Not only his theological but also his aesthetic works have of late become the subject of universal study in Europe."[178][195]

Early-20th-century reception

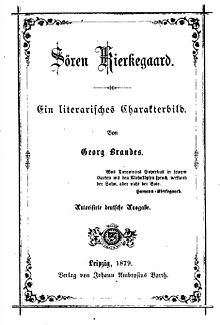

The first academic to draw attention to Kierkegaard was fellow Dane Georg Brandes, who published in German as well as Danish. Brandes gave the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard in Copenhagen and helped bring him to the attention of the European intellectual community.[196] Brandes published the first book on Kierkegaard's philosophy and life, Søren Kierkegaard, ein literarisches Charakterbild. Autorisirte deutsche Ausg (1879)[197] which Adolf Hult said was a "misconstruction" of Kierkegaard's work and "falls far short of the truth".[198] Brandes compared him to Hegel and Tycho Brahe in Reminiscences of my Childhood and Youth[199] (1906). Brandes also discussed the Corsair Affair in the same book.[200] Brandes opposed Kierkegaard's ideas in the 1911 edition of the Britannica.[178][201][202] Brandes compared Kierkegaard to Nietzsche as well.[203] He also mentioned Kierkegaard extensively in volume 2 of his 6 volume work, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature (1872 in German and Danish, 1906 English).[178][204][205]

Swedish author Waldemar Rudin published Sören Kierkegaards person och författarskap – ett försök in 1880.[206] During the 1890s, Japanese philosophers began disseminating the works of Kierkegaard.[207] Tetsuro Watsuji was one of the first philosophers outside of Scandinavia to write an introduction on his philosophy, in 1915.

Harald Høffding wrote an article about him in A brief history of modern philosophy (1900).[178] Høffding mentioned Kierkegaard in Philosophy of Religion 1906, and the American Journal of Theology[208] (1908) printed an article about Hoffding's Philosophy of Religion. Then Høffding repented of his previous convictions in The problems of philosophy (1913).[178] Høffding was also a friend of the American philosopher William James, and although James had not read Kierkegaard's works, as they were not yet translated into English, he attended the lectures about Kierkegaard by Høffding and agreed with much of those lectures. James' favorite quote from Kierkegaard came from Høffding: "We live forwards but we understand backwards". Kierkegaard wrote of moving forward past the irresolute good intention:

One thing James did have in common with Kierkegaard was respect for the single individual, and their respective comments may be compared in direct sequence as follows: "A crowd is indeed made up of single individuals; it must therefore be in everyone's power to become what he is, a single individual; no one is prevented from being a single individual, no one, unless he prevents himself by becoming many. To become a crowd, to gather a crowd around oneself, is on the contrary to distinguish life from life; even the most well-meaning one who talks about that, can easily offend a single individual."[209] In his book A Pluralistic Universe, James stated that, "Individuality outruns all classification, yet we insist on classifying every one we meet under some general label. As these heads usually suggest prejudicial associations to some hearer or other, the life of philosophy largely consists of resentments at the classing, and complaints of being misunderstood. But there are signs of clearing up for which both Oxford and Harvard are partly to be thanked."[210]

The Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics had an article about Kierkegaard in 1908. The article began:

Friedrich von Hügel wrote about Kierkegaard in his 1913 book, Eternal life: a study of its implications and applications, where he said: "Kierkegaard, the deep, melancholy, strenuous, utterly uncompromising Danish religionist, is a spiritual brother of the great Frenchman, Blaise Pascal, and of the striking English Tractarian, Hurrell Froude, who died young and still full of crudity, yet left an abiding mark upon all who knew him well."[212][213]

John George Robertson[214] wrote an article called Soren Kierkegaard in 1914: "Notwithstanding the fact that during the last quarter of a century, we have devoted considerable attention to the literatures of the North, the thinker and man of letters whose name stands at the head of the present article is but little known to the English-speaking world. The Norwegians, Ibsen and Bjørnson, have exerted a very real power on our intellectual life, and for Bjørnson we have cherished even a kind of affection. But Kierkegaard, the writer who holds the indispensable key to the intellectual life of Scandinavia, to whom Denmark in particular looks up as her most original man of genius in the nineteenth century, we have wholly overlooked."[215] Robertson wrote previously in Cosmopolis (1898) about Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.[216] Theodor Haecker wrote an essay titled, Kierkegaard and the Philosophy of Inwardness in 1913 and David F. Swenson wrote a biography of Søren Kierkegaard in 1920.[178] Lee M. Hollander translated parts of Either/Or, Fear and Trembling, Stages on Life's Way, and Preparations for the Christian Life (Practice in Christianity) into English in 1923,[217] with little impact. Swenson wrote about Kierkegaard's idea of "armed neutrality"[218] in 1918 and a lengthy article about Søren Kierkegaard in 1920.[219][220] Swenson stated: "It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world."[221]

Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Stekel (1868–1940) referred to Kierkegaard as the "fanatical follower of Don Juan, himself the philosopher of Don Juanism" in his book Disguises of Love.[222] German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) stated he had been reading Kierkegaard since 1914 and compared Kierkegaard's writings with Friedrich Hegel's Phenomenology of Mind and the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Jaspers saw Kierkegaard as a champion of Christianity and Nietzsche as a champion for atheism.[223] Later, in 1935, Karl Jaspers emphasized Kierkegaard's (and Nietzsche's) continuing importance for modern philosophy[224]

German and English translators of Kierkegaard's works

Albert Barthod began translating Kierkegaard's works into German as early as 1873.[225] Hermann Gottsche published Kierkegaard's Journals in 1905. It had taken academics 50 years to arrange his journals.[226] Kierkegaard's main works were translated into German by Christoph Schrempf from 1909 onwards.[227] Emmanuel Hirsch released a German edition of Kierkegaard's collected works from 1950 onwards.[227] Both Harald Hoffding's and Schrempf's books about Kierkegaard were reviewed in 1892.[228][229]

In the 1930s, the first academic English translations,[230] by Alexander Dru, David F. Swenson, Douglas V. Steere, and Walter Lowrie appeared, under the editorial efforts of Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams,[231] one of the members of the Inklings.[232][233] Thomas Henry Croxall, another early translator, Lowrie, and Dru all hoped that people would not just read about Kierkegaard but would actually read his works.[234] Dru published an English translation of Kierkegaard's Journals in 1958;[235] Alastair Hannay translated some of Kierkegaard's works.[64] From the 1960s to the 1990s, Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong translated his works more than once.[236][237] The first volume of their first version of the Journals and Papers (Indiana, 1967–1978) won the 1968 U.S. National Book Award in category Translation.[236][238] They both dedicated their lives to the study of Søren Kierkegaard and his works, which are maintained at the Howard V. and Edna H. Hong Kierkegaard Library.[239] Jon Stewart from the University of Copenhagen has written extensively about Søren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard's influence on Karl Barth's early theology

Kierkegaard's influence on Karl Barth's early theology is evident in The Epistle to the Romans 1918, 1921, 1933.

Barth read at least three volumes of Kierkegaard's works: Practice in Christianity, The Moment, and an Anthology from his journals and diaries. Almost all key terms from Kierkegaard which had an important role in The Epistle to the Romans can be found in Practice in Christianity. The concept of the indirect communication, the paradox, and the moment of Practice in Christianity, in particular, confirmed and sharpened Barth's ideas on contemporary Christianity and the Christian life.

Wilhelm Pauk wrote in 1931 (Karl Barth Prophet of a New Christianity) that Kierkegaard's use of the Latin phrase Finitum Non Capax Infiniti (the finite does not (or cannot) comprehend the infinite) summed up Barth's system.[241] David G. Kingman and Adolph Keller each discussed Barth's relationship to Kierkegaard in their books, The Religious Educational Values in Karl Barth's Teachings (1934) and Karl Barth and Christian Unity (1933). Keller notes the splits that happen when a new teaching is introduced and some assume a higher knowledge from a higher source than others.

Students of Kierkegaard became a "group of dissatisfied, excited radicals" when under Barthianism. Eduard Geismar (1871-1939), who gave Lectures on Kierkegaard in March 1936 wasn't radical enough for them. Barthiasm was opposed to the objective treatment of religious questions and to the sovereignty of man in the existential meeting with the transcendent God. But just as student of Hegel broke off into Right and Left so did the German followers of Barth.

Barth endorses the main theme from Kierkegaard but also reorganizes the scheme and transforms the details. He expands the theory of indirect communication to the field of Christian ethics; he applies the concept of unrecognizability to the Christian life. He coins the concept of the "paradox of faith" since the form of faith entails a contradictory encounter of God and human beings. He also portrayed the contemporaneity of the moment when in crisis a human being desperately perceives the contemporaneity of Christ. In regard to the concept of indirect communication, the paradox, and the moment, the Kierkegaard of the early Barth is a productive catalyst.[243]

Later-20th-century reception

Logic and human reasoning are inadequate to comprehend truth, and in this emphasis Dostoevsky speaks entirely the language of Kierkegaard, of whom he had never heard. Christianity is a way of life, an existential condition. Again, like Kierkegaard, who affirmed that suffering is the climate in which man's soul begins to breathe. Dostoevsky stresses the function of suffering as part of God's revelation of truth to man. Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka by William Hubben 1952 McMillan p. 83William Hubben compared Kierkegaard to Dostoevsky in his 1952 book Four Prophets of Our Destiny, later titled Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka.

In 1955 Morton White wrote about the word "exists" and Kierkegaard's idea of God's is-ness.

John Daniel Wild noted as early as 1959 that Kierkegaard's works had been "translated into almost every important living language including Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, and it is now fair to say that his ideas are almost as widely known and as influential in the world as those of his great opponent Hegel, still the most potent of world philosophers."[244]

Mortimer J. Adler wrote the following about Kierkegaard in 1962:

In 1964 Life Magazine traced the history of existentialism from Heraclitus (500BC) and Parmenides over the argument over The Unchanging One as the real and the state of flux as the real. From there to the Old Testament Psalms and then to Jesus and later from Jacob Boehme (1575–1624) to Rene Descartes (1596–1650) and Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) and then on to Nietzsche and Paul Tillich. Dostoevski and Camus are attempts to rewrite Descartes according to their own lights and Descartes is the forefather of Sartre through the fact that they both used a "literary style." The article goes on to say,

Kierkegaard's comparatively early and manifold philosophical and theological reception in Germany was one of the decisive factors of expanding his works' influence and readership throughout the world.[245][246] Important for the first phase of his reception in Germany was the establishment of the journal Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Ages) in 1922 by a heterogeneous circle of Protestant theologians: Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Rudolf Bultmann and Friedrich Gogarten.[247] Their thought would soon be referred to as dialectical theology.[247] At roughly the same time, Kierkegaard was discovered by several proponents of the Jewish-Christian philosophy of dialogue in Germany, namely by Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner, and Franz Rosenzweig.[248] In addition to the philosophy of dialogue, existential philosophy has its point of origin in Kierkegaard and his concept of individuality.[249] Martin Heidegger sparsely refers to Kierkegaard in Being and Time (1927),[250] obscuring how much he owes to him.[251][252][253] Walter Kaufmann discussed Sartre, Jaspers, and Heidegger in relation to Kierkegaard, and Kierkegaard in relation to the crisis of religion in the 1960s.[254] Later, Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling (Series Two) and The Sickness Unto Death (Series Three) were included in the Penguin Great Ideas Series (Two and Three).[255]

Philosophy and theology

Kierkegaard has been called a philosopher, a theologian,[256] the Father of Existentialism,[257][258][259] both atheistic and theistic variations,[260] a literary critic,[141] a social theorist,[261] a humorist,[262] a psychologist,[2] and a poet.[263] Two of his influential ideas are "subjectivity",[a] and the notion popularly referred to as "leap of faith".[232] However, the Danish equivalent to the English phrase "leap of faith" does not appear in the original Danish nor is the English phrase found in current English translations of Kierkegaard's works. Kierkegaard does mention the concepts of "faith" and "leap" together many times in his works.[265]

The leap of faith is his conception of how an individual would believe in God or how a person would act in love. Faith is not a decision based on evidence that, say, certain beliefs about God are true or a certain person is worthy of love. No such evidence could ever be enough to completely justify the kind of total commitment involved in true religious faith or romantic love. Faith involves making that commitment anyway. Kierkegaard thought that to have faith is at the same time to have doubt. So, for example, for one to truly have faith in God, one would also have to doubt one's beliefs about God; the doubt is the rational part of a person's thought involved in weighing evidence, without which the faith would have no real substance. Someone who does not realize that Christian doctrine is inherently doubtful and that there can be no objective certainty about its truth does not have faith but is merely credulous. For example, it takes no faith to believe that a pencil or a table exists, when one is looking at it and touching it. In the same way, to believe or have faith in God is to know that one has no perceptual or any other access to God, and yet still has faith in God.[266] Kierkegaard writes, "doubt is conquered by faith, just as it is faith which has brought doubt into the world".[267][268]

Kierkegaard also stresses the importance of the self, and the self's relation to the world, as being grounded in self-reflection and introspection. He argued in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity." This has to do with a distinction between what is objectively true and an individual's subjective relation (such as indifference or commitment) to that truth. People who in some sense believe the same things may relate to those beliefs quite differently. Two individuals may both believe that many of those around them are poor and deserve help, but this knowledge may lead only one of them to decide to actually help the poor.[269] This is how Kierkegaard put it: "What a priceless invention statistics are, what a glorious fruit of culture, what a characteristic counterpart to the de te narratur fabula [the tale is told about you] of antiquity. Schleiermacher so enthusiastically declares that knowledge does not perturb religiousness, and that the religious person does not sit safeguarded by a lightning rod and scoff at God; yet with the help of statistical tables one laughs at all of life."[270][271] In other words, Kierkegaard says: "Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor's distance from everyday life – or the learner who should put it to use?"[272] This is how it was summed up in 1940:

Kierkegaard primarily discusses subjectivity with regard to religious matters. As already noted, he argues that doubt is an element of faith and that it is impossible to gain any objective certainty about religious doctrines such as the existence of God or the life of Christ. The most one could hope for would be the conclusion that it is probable that the Christian doctrines are true, but if a person were to believe such doctrines only to the degree they seemed likely to be true, he or she would not be genuinely religious at all. Faith consists in a subjective relation of absolute commitment to these doctrines.[273]

Philosophical criticism

Kierkegaard's famous philosophical 20th-century critics include Theodor Adorno and Emmanuel Levinas. Non-religious philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger supported many aspects of Kierkegaard's philosophical views,[274] but rejected some of his religious views.[275][276] One critic wrote that Adorno's book Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic is "the most irresponsible book ever written on Kierkegaard"[277] because Adorno takes Kierkegaard's pseudonyms literally and constructs a philosophy that makes him seem incoherent and unintelligible. Another reviewer says that "Adorno is [far away] from the more credible translations and interpretations of the Collected Works of Kierkegaard we have today."[123]

Levinas' main attack on Kierkegaard focused on his ethical and religious stages, especially in Fear and Trembling. Levinas criticises the leap of faith by saying this suspension of the ethical and leap into the religious is a type of violence (the "leap of faith" of course, is presented by a pseudonym, thus not representing Kierkegaard's own view, but intending to prompt the exact kind of discussion engaged in by his critics). He states: "Kierkegaardian violence begins when existence is forced to abandon the ethical stage in order to embark on the religious stage, the domain of belief. But belief no longer sought external justification. Even internally, it combined communication and isolation, and hence violence and passion. That is the origin of the relegation of ethical phenomena to secondary status and the contempt of the ethical foundation of being which has led, through Nietzsche, to the amoralism of recent philosophies."[278]

Levinas pointed to the Judeo-Christian belief that it was God who first commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and that an angel commanded Abraham to stop. If Abraham were truly in the religious realm, he would not have listened to the angel's command and should have continued to kill Isaac. To Levinas, "transcending ethics" seems like a loophole to excuse would-be murderers from their crime and thus is unacceptable.[279][incomplete short citation] One interesting consequence of Levinas' critique is that it seemed to reveal that Levinas viewed God as a projection of inner ethical desire rather than an absolute moral agent.[280] However, one of Kierkegaard's central points in Fear and Trembling was that the religious sphere entails the ethical sphere; Abraham had faith that God is always in one way or another ethically in the right, even when He commands someone to kill. Therefore, deep down, Abraham had faith that God, as an absolute moral authority, would never allow him in the end to do something as ethically heinous as murdering his own child, and so he passed the test of blind obedience versus moral choice. He was making the point that God as well as the God-Man Christ doesn't tell people everything when sending them out on a mission and reiterated this in Stages on Life's Way.

Sartre objected to the existence of God: If existence precedes essence, it follows from the meaning of the term sentient that a sentient being cannot be complete or perfect. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre's phrasing is that God would be a pour-soi (a being-for-itself; a consciousness) who is also an en-soi (a being-in-itself; a thing) which is a contradiction in terms.[275][281] Critics of Sartre rebutted this objection by stating that it rests on a false dichotomy and a misunderstanding of the traditional Christian view of God.[282] Kierkegaard has Judge Vilhelm express the Christian hope this way in Either/Or:

Sartre agreed with Kierkegaard's analysis of Abraham undergoing anxiety (Sartre calls it anguish), but claimed that God told Abraham to do it. In his lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism, Sartre wondered whether Abraham ought to have doubted whether God actually spoke to him.[275] In Kierkegaard's view, Abraham's certainty had its origin in that "inner voice" which cannot be demonstrated or shown to another ("The problem comes as soon as Abraham wants to be understood").[283] To Kierkegaard, every external "proof" or justification is merely on the outside and external to the subject.[284] Kierkegaard's proof for the immortality of the soul, for example, is rooted in the extent to which one wishes to live forever.[285]

Faith was something that Kierkegaard often wrestled with throughout his writing career; under both his real name and behind pseudonyms, he explored many different aspects of faith. These various aspects include faith as a spiritual goal, the historical orientation of faith (particularly toward Jesus Christ), faith being a gift from God, faith as dependency on a historical object, faith as a passion, and faith as a resolution to personal despair. Even so, it has been argued that Kierkegaard never offers a full, explicit and systematic account of what faith is.[73] Either/Or was published 20 February 1843; it was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling's Philosophy of Revelation. According to the Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Religion, Either/Or (vol. 1) consists of essays of literary and music criticism, a set of romantic-like-aphorisms, a whimsical essay on how to avoid boredom, a panegyric on the unhappiest possible human being, a diary recounting a supposed seduction, and (vol. II) two enormous didactic and hortatory ethical letters and a sermon.[76][77] This opinion is a reminder of the type of controversy Kierkegaard tried to encourage in many of his writings both for readers in his own generation and for subsequent generations as well.

Kierkegaardian scholar Paul Holmer[286] described Kierkegaard's wish in his introduction to the 1958 publication of Kierkegaard's Edifying Discourses where he wrote:

Later, Naomi Lebowitz explained them this way: The edifying discourses are, according to Johannes Climacus, "humoristically revoked" (CUP, 244, Swenson, Lowrie 1968) for unlike sermons, they are not ordained by authority. They start where the reader finds himself, in immanent ethical possibilities and aesthetic repetitions, and are themselves vulnerable to the lure of poetic sirens. They force the dialectical movements of the making and unmaking of the self before God to undergo lyrical imitations of meditation while the clefts, rifts, abysses, are everywhere to be seen.[288]

Political views

Throughout retrospective analyses Kierkegaard has been viewed as an apolitical philosopher.[289][290][291] Despite this Kierkegaard did publish works of a political nature such as his first published essay, criticizing the women's suffragette movement.[289]

Kierkegaard frequently challenged the cultural norms of his time, particularly the quick and uncritical adoption of Hegelianism by the philosophical establishment, arguing that Hegel's system "omits the individual", and therefore presents an ultimately limited view of life.[292] He attacked Hegelianism via elaborate parody throughout his works from Either/Or to Concluding Unscientific Postscript.[289] Despite his objections to Hegelianism, he expressed an admiration for Hegel personally and would even regard his system favourably if it was proposed as a thought experiment[289]

Kierkegaard also attacked the elements of culture that the Enlightenment had produced such as the natural sciences and reason, viewing the natural sciences, in particular, to have "Absolutely no benefit" and that:

Kierkegaard leaned towards conservatism,[291][293] being a personal friend of Danish king Christian VIII, whom he viewed as the moral superior of every Danish man, woman, and child. He argued against democracy, calling it "the most tyrannical form of government," arguing in favour of monarchy saying "Is it tyranny when one person wants to rule leaving the rest of us others out? No, but it is tyranny when all want to rule."[292] Kierkegaard held strong contempt for the media, describing it as "the most wretched, the most contemptible of all tyrannies".[294][295] He was critical of the Danish public at the time, labeling them as "the most dangerous of all powers and the most meaningless,"[294] writing further in Two Ages: A Literary Review that:

Some interpret Kierkegaard’s thought as implying that in regards to serving God, sexuality is irrelevant "before God not only for men and women, but also for homosexuals and heterosexuals".[297][b]

Kierkegaard's political philosophy has been likened to Neo-Conservatism, despite its major influence on radical and anti-traditional thinkers, religious and secular, such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Jean Paul Sartre.[299] It has also been likened to anti-establishment thought and has been described as "a starting point for contemporary political theories".[290]

Legacy