|

Ayn Rand (1905 - 1982)

|

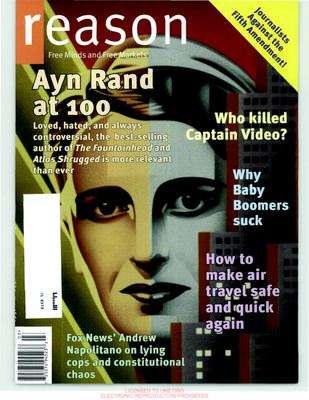

The daughter of a chemist, Ayn Rand immigrated to the United States in 1926 with the thought of becoming a screenwriter. Cecil B. DeMille made her an extra in The King of Kings, and she emerged from the crowd scenes to become a fervent advocate of laissez-faire capitalism. The ideological message embedded in her best-selling novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged endeared her to admirers as diverse as Alan Greenspan, Hugh Hefner, and Clarence Thomas.

* * * * * * * * * *

Continuation of an 8-Part Series

Part 1 -

Ayn Rand

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Ayn rand)

Ayn Rand (/aɪn/;] born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum; February 2, [O.S. January 20] 1905 – March 6, 1982) was a Russian-American writer and philosopher. She is known for her two best-selling novels, The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, and for developing a philosophical system she named Objectivism. Born and educated in Russia, she moved to the United States in 1926. She had a play produced on Broadway in 1935 and 1936. After two early novels that were initially unsuccessful, she achieved fame with her 1943 novel, The Fountainhead. In 1957, Rand published her best-known work, the novel Atlas Shrugged. Afterward, she turned to non-fiction to promote her philosophy, publishing her own periodicals and releasing several collections of essays until her death in 1982.

Rand advocated reason as the only means of acquiring knowledge and rejected faith and religion. She supported rational and ethical egoism and rejected altruism. In politics, she condemned the initiation of force as immoraland opposed collectivism and statism as well as anarchism, instead supporting laissez-faire capitalism, which she defined as the system based on recognizing individual rights, including property rights. In art, Rand promoted romantic realism. She was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her, except for Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas and classical liberals.

Literary critics received Rand's fiction with mixed reviews and academia generally ignored or rejected her philosophy, though academic interest has increased in recent decades. The Objectivist movement attempts to spread her ideas, both to the public and in academic settings. She has been a significant influence among libertarians and American conservatives.

Ayn Rand

| |

|---|---|

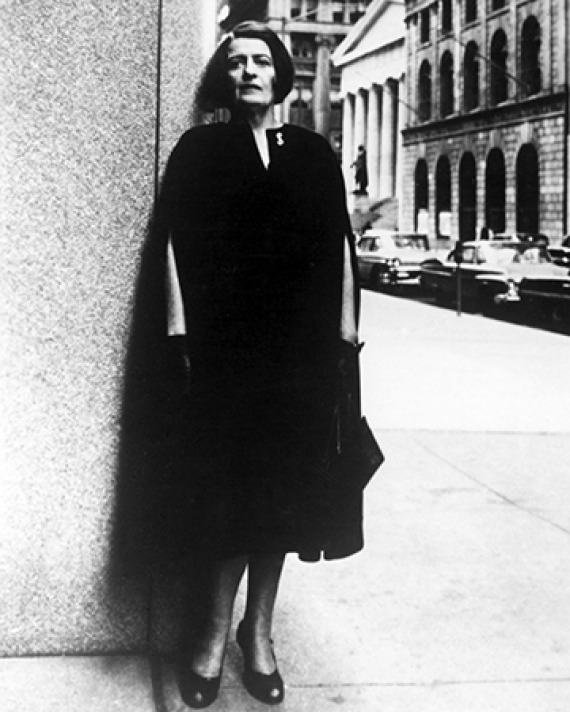

Rand in 1943

| |

| Native name |

Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум

(Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum) |

| Born | February 2, 1905 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 6, 1982 (aged 77) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, United States |

| Pen name | Ayn Rand |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | English |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Petrograd State University (diploma in history, 1924) |

| Period | 1934–1982 |

| Subject | Philosophy |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | Prometheus Award Hall of Fame inductee in 1987 (for Anthem) and co-inaugural inductee in 1983 (for Atlas Shrugged) |

| Spouse |

Frank O'Connor

(

m. 1929; his death 1979) |

| Signature |  |

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Rand called her philosophy "Objectivism", describing its essence as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute". She considered Objectivism a systematic philosophy and laid out positions on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.

In metaphysics, Rand supported philosophical realism, and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion.

In epistemology, she considered all knowledge to be based on sense perception, the validity of which she considered axiomatic, and reason, which she described as "the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man's senses". She rejected all claims of non-perceptual or a priori knowledge, including "'instinct,' 'intuition,' 'revelation,' or any form of 'just knowing'". In her Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, Rand presented a theory of concept formation and rejected the analytic–synthetic dichotomy.

In ethics, Rand argued for rational and ethical egoism (rational self-interest), as the guiding moral principle. She said the individual should "exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself". She referred to egoism as "the virtue of selfishness" in her book of that title, in which she presented her solution to the is-ought problem by describing a meta-ethical theory that based morality in the needs of "man's survival qua man".[She condemned ethical altruism as incompatible with the requirements of human life and happiness, and held that the initiation of force was evil and irrational, writing in Atlas Shrugged that "Force and mind are opposites."

Rand's political philosophy emphasized individual rights (including property rights), and she considered laissez-faire capitalism the only moral social system because in her view it was the only system based on the protection of those rights. She opposed statism, which she understood to include theocracy, absolute monarchy, Nazism, fascism, communism, democratic socialism, and dictatorship. Rand believed that natural rights should be enforced by a constitutionally limited government. Although her political views are often classified as conservative or libertarian, she preferred the term "radical for capitalism". She worked with conservatives on political projects, but disagreed with them over issues such as religion and ethics. She denounced libertarianism, which she associated with anarchism. She rejected anarchism as a naïve theory based in subjectivism that could only lead to collectivism in practice.

In aesthetics, Rand defined art as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments". According to her, art allows philosophical concepts to be presented in a concrete form that can be easily grasped, thereby fulfilling a need of human consciousness. As a writer, the art form Rand focused on most closely was literature, where she considered romanticism to be the approach that most accurately reflected the existence of human free will. She described her own approach to literature as "romantic realism".

Rand acknowledged Aristotle as her greatest influence and remarked that in the history of philosophy she could only recommend "three A's"—Aristotle, Aquinas, and Ayn Rand.In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, when asked where her philosophy came from she responded: "Out of my own mind, with the sole acknowledgement of a debt to Aristotle, the only philosopher who ever influenced me. I devised the rest of my philosophy myself."However, she also found early inspiration in Friedrich Nietzsche,and scholars have found indications of his influence in early notes from Rand's journals, in passages from the first edition of We the Living (which Rand later revised),and in her overall writing style. However, by the time she wrote The Fountainhead, Rand had turned against Nietzsche's ideas, and the extent of his influence on her even during her early years is disputed.

Rand considered her philosophical opposite to be Immanuel Kant, whom she referred to as “the most evil man in mankind’s history”, primarily for his philosophy regarding the limitations of reason.

Rand said her most important contributions to philosophy were her "theory of concepts, ethics, and discovery in politics that evil—the violation of rights—consists of the initiation of force". She believed epistemology was a foundational branch of philosophy and considered the advocacy of reason to be the single most significant aspect of her philosophy, stating: "I am not primarily an advocate of capitalism, but of egoism; and I am not primarily an advocate of egoism, but of reason. If one recognizes the supremacy of reason and applies it consistently, all the rest follows."

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Rand's More Popular Books

The Fountainhead is the revolutionary literary vision that sowed the seeds of Objectivism, Ayn Rand's groundbreaking philosophy, and brought her immediate worldwide acclaim. This modern classic is the story of intransigent young architect Howard Roark, whose integrity was as unyielding as granite...of Dominique Francon, the exquisitely beautiful woman who loved Roark passionately, but married his worst enemy...and of the fanatic denunciation unleashed by an enraged society against a great creator. As fresh today as it was then, Rand’s provocative novel presents one of the most challenging ideas in all of fiction—that man’s ego is the fountainhead of human progress...

Peopled by larger-than-life heroes and villains, charged with towering questions of good and evil, Atlas Shrugged is Ayn Rand’s magnum opus: a philosophical revolution told in the form of an action thriller. It is the story of a man who said that he would stop the motor of the world—and did. Was he a destroyer or the greatest of liberators? Why did he have to fight his battle, not against his enemies but against those who needed him most—and his hardest battle against the woman he loved? What is the world's motor—and the motive power of every man?

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

My Perspective of Ayn Rand

by R.E. Slater

August 3, 2020

August 3, 2020

My own politics are generally informed by the desire to live in a ‘good’ society. I’m pretty casual about what ‘good’ means, precisely: some kind of pluralist satisficing compromise borne of reflective equilibrium. Most of us want a society that is free, genuinely meritocratic, absent egregious social strife and inequality (for basic Rawlsian reasons), with just laws and a representative government and opportunities to develop one’s talents and interests without too much interference. - Nicholas McGinnis

For Ayn Rand fans my review of Rand's objectivist philosophy of life will not be very favorable. Although I can appreciate what she is saying, I cannot appreciate the ultimate outcome of how, or why, she is saying it. The last two articles listed in this posting may help discern the good of Rand without compromising basic humanitarian principles as too many authoritarian (socialist/communist) or non-authoritarian (democratic/captilist) economies do these days.

In fact, this review here today will hope to offer why we study eccentric ideas to perhaps capture a glimmer of what might be helpful in recreating a better socialist or democratic economy than we have now. I say this knowing that an ecological society must develop into being lest this anthropocene age we now live in dies along with us in it.

Russian in the 70s, and China in the 90s, have been working on some form of ecological civilization. But if it is to be fully instructive, this type of society will also need to affect how their socialism interacts with their form of authoritarian government in raw terms of equality and freedom. The same with the United States which is only now beginning to realize its economy must adapt or die. Thus today's thoughts on Rand.

For those who regard Ayn Rand's materialistic philosophy as a proper personal and political deportment of what Christianity and its Western capitalistic policies should be, think again. Rand's version of predatory capitalism is the exact opposite on every level of personal and social good, or for that matter, the development of an ecological civilization.

Those Christian theologies which embrace this form of American individualism are anathema to the teachings of Christ. And when the non-Christian sees more clearly through Rand's self-centered veils than the church does, then God's rebuke lies with His people, who have embraced Rand's outlook to the exclusion of Jesus' teachings against accumulating money for money's sake.

- Rand says to accumulate wealth every way you can. And when you do, collect more of it and build bigger empires to yourself. This might also be termed crass consumerism.

- Extreme Capitalists say building bigger empires employs more people. That it provides for the welfare and security of surrounding communities when you exercise greed and power by employing workers and communities into a participation with empire building. However, without providing parallel investment-sharing profit plans for workers and their communities personal wages cannot keep up with rising costs; poverty rises in parallel with neglected community programs; and gentrification sets in pushing out those unable to participate in the new economic prosperity. Capitalism must always insure those labourers who build the system enjoy the benefits of the system through equitable profit-sharing plans while assisting communities in sharing the created wealth through education, apprenticeship programs, and non-profit organizations created to lift up the abandoned and overlooked.

- Jesus says how you accumulate wealth is important. It must be collected morally and ethically. And if you do, to remember the poor, for no higher work may we do than to aid the impoverished and help the oppressed in all matters spiritual, legal, economic, and personal. This means that even the merest welfare program teach receiving individuals and communities "how to fish, not simply to eat the fish." I believe this would be in the spirit of Ayn Rand's objectivist philosophy of self-sustainance.

- Today's Ecological Christian might also add, in the distribution of monies remember to empower nature by which all are helped and fed. To do all that you can to restore clean water, clean air, and clean land. These are important to nature and to all life itself.

- And finally, rather than practicing as a life philosophy crass materialism or predatory capitalism that an ecologically-driven form of capitalism takes thought to replenish, rebuild, restore, and transform what it thinks to take and use leaving it better than it was. This also goes for the individuals and communities who are affected or affecting. It teaches an elevated form of "the circle of life" which measures plans, purposes, processes, and results, by whether it is restorative for people and for the environment it affects.

In today's capitalist societies, business cultures, secularized churches, and popularized nationalisms it is irresponsible to ease collective guilt by justifying overlooking socially oppressive practices on the basis of Ayn Rand's competitive laissez faire policies based in self-interest, self-happiness, and self-preservation (she deigns any-and-all forms of altruism, religion, and spiritual awareness).

Rand's metaphysic rests on the self and its identity of the self. We might call her objectivist philosophy a kind of quasi-philosophy resting on a form of quasi-capitalism which may find their eclectic basis in many other truer forms of philosophical and economic deportments. But what appeals to her the most is individualism and happiness. There is no God and no driving purpose of the evolving universe except to survive and win in the bleakest of Darwin's evolutionary terms.

Speaking of Darwin, I have made the case time-and-again that process evolution neither denies Darwinism nor modifies it. That we embrace Darwinian evolution fully and completely. However, when using its model, as we rightfully must, we adjust its foundation, processes, and teleology by putting God under it, in it, over it, and at its end. We might call this metaphysic evolutionary creationism or a process-philosophy driven process-evolution but regardless, we never modify its science excepting that God is the Creator, Sustainer, and full end of His evolving Creation. Thus, nothing is purposeless or and end to itself - though Ayn Rand would like that. God is all-in-all, even in our economics, its goals, usage, and results.

It is our responsibility to then be in sync with this type of evolutionary process creation, not out of sync with it. If we don't understand process philosophy or its corollary, process theology, than it is up to us as experts in our fields to understand its metaphysic so as to incorporate it into our academic disciplines.

In effect then, Rand proposes a hard-heartedness or personal jadedness to the suffering of others. She does not recommend Good-Samaritan practices of compassion. She offers a bleak worldview with no better metaphysical goal than one that is self-seeking, pleasure-filled, and with goals of personal happiness without regard of personal or corporate caretake or uplift for the other or, for that matter, the nature which lies everywhere around us.

For Ayn Rand, the good of life, the goal of life, the satisfaction found in life, are all built around personal happiness, wealth, power, self-preservation, and release from any obstructions by the state or any other interfering entities such as taxation or moral duty.

The Roman Caesars, along with Rome's ruling classes of the wealthy and empowered, had built their societies exquisitely around the twin pillars of self-happiness and self-rule to the harm and suffering of the rest of humanity they touched. Yes, they built great roads, great civil engineering projects, instilled Western civilization's many forms of Roman justice, trade, and economic uplift to the world it conquered. But with it came again the world's great suffering, stricter forms of class hierarchies, removal and deportment of local populations through desettlement and enslavement, oppressive taxation, and every pitiful thing which comes with economic disparity and loss of freedom through authoritarianism. Rand's form of economy would be very Roman like offering both the good and the bad.

So to those business people, politicians, or church people espousing Ayn Rand's form of capitalism let it also be know that there is a moral duty and ethical compass to share the wealth the masses have provided to you but are not profiting by. It means incorporating good profit-sharing plans into businesses, lowering taxes on the masses, and taxing the wealthy for the betterment of the community. That wealth is not for the pitiful amassing of gluttonous power and ease. It means strengthening community non-profits and reducing wasteful social-agency bureaucracies. It means creating a generous capitalism - or stepping away from capitalism altogether - towards an environmental form of "ecological social capitalism" which shares equally in "bounty and liberty of the one to the other in relationship with creation itself."

I leave you with Gore Vidal summation of Ayn Rand's Objectivist Philosophy:

[Excerpt] "The late Gore Vidal was scathing even decades ago, writing in 1961 that Rand has a great attraction for simple people who are puzzled by organized society, who object to paying taxes, who dislike the 'welfare' state, who feel guilt at the thought of the suffering of others but who... harden their hearts.... Ayn Rand’s “philosophy” is nearly perfect in its immorality, which makes the size of her audience all the more ominous and symptomatic."

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Another Perspective of Ayn Rand

Another Perspective of Ayn Rand

by Rance Darity

August 3, 2020

I find it the height of irony and hypocrisy that the philosophy and economic ideas of Ayn Rand hold so much prominence within Christian conservatives as Rand specifically, and in no uncertain terms, stated that her ideals were directly at odds, and in opposition to, those of Jesus. - Anon

What the extreme Republican political Trump-favoring movement is doing right now is doubling down on the use of scare words like ‘socialism.’

Trump is constantly playing the "S" card and using demagogic arguments as justification for opposing President-elect Biden and of course re-electing himself into a second term. Don’t fall for it.

But I get it. After a President who basically does nothing, who turned health briefings into political rallies, who criticized governors who tried to implement the Federal guidelines coming out of his very own administration, who daily undercut Dr. Fauci, the CDC, WHO, and the Surgeon General, and who has yet to come up with a coherent and effective national policy to confront this ever spreading pandemic, then anything or anyone different from him would indeed, by comparison, look like a socialist to his followers.

In reality, since FDR, America has progressively helped remedy many of our most difficult and fundamental challenges. We haven’t arrived by a long shot, but the collective effort of Americans via the Federal government has helped fund public education and public health. Has devised programs to assist the poor and elderly. And has made countless programs like Social Security and Medicare-Medicaid available and successfully implemented for millions.

In other words, we have worked together to ‘redistribute’ God’s bountiful blessings so that it does not remain only in the reach of the rich and powerful for careless purposes.

If that is socialism, then God help us, send us more of it.

But of course, this isn’t about socialism versus capitalism altogether.

It’s about loving our neighbor as we love ourselves. It’s about doing all the good we can possibly do to lift one another up and come to each other’s aid. It’s about standing together instead of standing apart.

In fact, it is about taking the teachings of Jesus and other compassionate leaders seriously enough to translate them into sound policy and benevolent practice.

Donald Trump doesn’t get that. Neither do his followers evidently. He has one goal in mind and it isn’t to help you and me. It certainly isn’t to protect us. It’s all about him and his syncophants.

And unfortunately, Trump will use every fascist lie in his little fascist book to win re-election.

Stand in his way. Vote him out. Vote for real leadership.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Ayn Rand, at her last lecture, 1981. | Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt | The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images |

I Visited the Secret Lair of the Ayn Rand Cult

Itay Meirson

April 4, 2020

Advocates of the theory propounded by philosopher Ayn Rand are radical individualists who are sometimes said to love humankind but to hate human beings. A surprising pre-pandemic journey to their headquarters in Los Angeles

Yesterday's World

Young readers may find this hard to believe, but the United States was not always an ill-fated land battered by disaster, piling up its dead and crying out for humanitarian aid from more developed countries. The old-timers among us remember a different America – an America where airlines fly millions of people from city to city every day, an America where people could walk in the street with their faces exposed, an America where every citizen has the right to shake the hand of the shopkeeper who just sold him a box of cornflakes, or a rifle. Yesterday’s world.

And suddenly, there’s the coronavirus. There’s no knowing where this contaminated rolling snowball will stop – perhaps it will even bring about the removal of President Trump from office in November? After all, it would take only a few thousand angry people in Pennsylvania and Florida to tilt the electoral scales from red to blue and to deliver the presidency to whoever is running against him (as long as that person is not a socialist Jew).

In any event, every such crisis has a deeper dimension than its potential influence on a presidential election. There is something thrilling, almost hypnotic, about the glorious helplessness America displays every time a devastating hurricane or a wind-borne virus transforms the country from an economic and technological superpower into a humanitarian disaster area. People dying in the streets was something we had in the Old Country – and surely not what we expected when we boarded the Mayflower almost exactly 400 years ago.

Sooner or later, our lips will utter the precise word: capitalism. After all, in the eyes of the progressive left, that’s the preexisting condition from which America has been suffering since the 17th century. It’s what prevents establishment of a public health system and makes the country so very vulnerable now. In the eyes of free-market advocates, however, capitalism is what turned mass death, hunger and disease from self-evident and almost certain phenomena in the pre-capitalist world, into something rarely seen in the modern landscape.

I always found people of the second type more interesting (right is always more interesting than left, everywhere and at any time). In fact, they interested me so much that ages ago I decided to visit America and get as close as possible to an extraordinarily fascinating cult that sprang up around an equally extraordinary and fascinating woman. It was a particularly marvelous journey that was still possible in another era – in early January 2020, before the first coronavirus victim in China wondered why he’d had a hard time breathing. I bought a plane ticket, because they were being sold, and disembarked in California, because it was permitted. Heady days.

Dollars and dystopia

Ten measures of dollar fetishism God gave to the world – nine were taken by writer and philosopher Ayn Rand, on whose behalf I’d boarded the plane. In “Atlas Shrugged,” her best-known, dystopian novel, the United States sinks into the depths of collectivist tyranny, and all that remains of the dying empire of capitalism is an isolated valley settled by a few hundred free enterprisers – individualists, the last true Americans. And what hangs like the sun in the skies? A sculpture of the dollar sign, fashioned of pure gold, one meter high. The same dollar sign – this time made of flowers, and almost two meters high – was placed on Ayn Rand’s grave in 1982 by the most loyal and tearful of her admirers, as it was being sealed.

William F. Buckley, Jr., the godfather of modern American conservatism, often accused Rand of wanting to substitute the sign of the dollar for the cross. He thereby erred in underestimating her intentions; the truth is that she would also have replaced the American flag with the dollar sign. Her fetishism for the letter S with a vertical stroke through it was not based on some aesthetic caprice, but on a rational argument that goes well beyond obsession: The dollar was the apex of creativity of the human spirit.

|

A box filled with dollar bills. Ten measures of dollar fetishism God gave to

the world – nine were taken by Ayn Rand. | Credit: Mark Lennihan, AP

|

Ayn Rand, née Alisa Rosenbaum, was born in 1905 to a bourgeois Jewish family in St. Petersburg – a reality that placed her on the wrong side of the Bolshevik revolution. In an alternative and not untenable scenario, she might have fled to Palestine and lived out her life in Tel Aviv as Miss Rosenbaum, the persnickety neighbor on the ground floor. But Alisa wanted America, America first, and crossed the ocean, where she eventually found work as a scriptwriter in Hollywood.

Rand would go on to divide her life between Manhattan and Hollywood, thrilled to the depths of her soul by the skyscrapers of the one and the factory of dreams of the other. Her most important novels, “Atlas Shrugged” and “The Fountainhead,” would sell 30 million copies between them. The rate of sales would accelerate with every economic crisis, with every public debate about the limits of the government’s power, with every election of a person named Barack Obama to the White House.

In the eyes of the progressive left, capitalism is the preexisting

condition from which America has been suffering since the 17th century.

The philosophical theory she propounded, which she called Objectivism, arises from every one of the too-many pages of her literary works and from numberless other theoretical texts she published, which are far more interesting.

When it comes to philosophy, political thought (radical capitalism, in this case) is built upon basic philosophical tiers: metaphysics, epistemology and ethics. Yes, lofty words, but in contrast to some contemporaneous philosophers, who did all they could to ensure that we would have no idea what they were talking about – with Rand everything is understood. She wrote clearly. In fact, the principal tenets of Objectivism can be summed up quite briefly:

- The first tier: metaphysics. Reality is objective. Facts exist. Beliefs or desires will not change them. In other words, it makes no difference how ardently you believe in God – that will not make him exist.

- The second tier: epistemology. Reason is man’s sole means of perceiving reality and his place within it. In short: Stop feeling things and use your brain, stupid.

- The third tier, ethics, is the crowning glory of Objectivism: egoism. Man is his own purpose. Do not sacrifice your life for the sake of others and do not ask others to sacrifice their lives for you.

What are the political implications of this architectural edifice? And then there is:

- the fourth tier: capitalism. The only system in which everyone lives for himself. Randian morality does not differentiate between human rights and property rights. Plundering a person’s property (by levying taxes, for example) – namely, dispossessing someone of the fruits of his labor, which promote his/her physical survival and his/her egoistic happiness – is equivalent to jailing him without a trial.

Capitalism, Rand decreed, need not be restrained, as liberals argue, nor need it be prettified and painted in colors that will conceal its true nature, as conservatives habitually do. We should take pride in, and feel blessed by, pure capitalism – the sort that is fueled by uncompromising rational egoism. “But capitalism runs contrary to the principle of equality!” readers of Haaretz and The New York Times will grumble. “Indeed,” Rand will reply to them, in her Russian accent, “and that is exactly what makes it just.”

When in virtually every Hollywood movie the “bad guy” is always the one who thinks only of himself and the “good guy” sacrifices himself for the benefit of others; when the leftist propaganda machine persuaded generations of Americans that the mega-industrialists of the 19th century – “the greatest humanitarians of mankind” – were nothing but “robber barons”; and when an American president (JFK) dares to preach, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” and is wildly applauded even by self-styled capitalists – after all this, Rand’s conclusion was that America is committing suicide by way of a cup of moral hemlock served up by left-wing intellectuals in their perverted thrust to establish an anti-rational nightmarish society.

From her point of view, this is a society whose raison d’être is adhering to the primitive tribal principle of serving “the common good.” It’s a society that’s suitable for a beehive but contrary to human nature: an egalitarian society.

Coronavirus will have its effect: 2020 is sure to be a boon

for the beneficiaries of Rand’s intellectual estate.

Instant cult

Objectivism became a cult the instant it was born, thanks largely to Rand’s enigmatic character, her psychological control over an inner circle of followers, and most of all, the obsessed devotion of young Nathaniel Branden, her intellectual right-hand (and secret lover), the cult builder, who made it clear to everyone that Objectivism is a package deal: If you are a radical capitalist but believe in God, go away and don’t come back; if you are an avowed atheist but believe in the state’s right to levy taxes, find yourself a different rabbi.

At regular meetings with her acolytes in her apartment on E. 36th Street in Manhattan, when the slightest hint of disagreement over her teachings was expressed by anyone present, even in a discussion about art, that person was sent into permanent exile.

The result: a cult that extols radical individualism, consisting of people whose philosophical, political, cultural, aesthetic, cinematic, literary and musical tastes are absolutely identical. To ensure the cult’s long-term survival, Rand ordained one of her brilliant pupils, Leonard Peikoff, as her legal and intellectual heir – that is, a human mouthpiece through whom she would continue to articulate her doctrine, even from beyond the grave.

|

| Rand’s desk on display at the institute. Only God knows how many social democrats were tortured on it. | Credit: Itay Meirson |

To be an Objectivist means to believe with complete faith (that is to say, to think solely based on reason) in one and only one proposition: “John Galt’s oath” – a reference to the protagonist of “Atlas Shrugged.” In the novel, every free enterpriser who wants to be admitted to the last capitalist paradise on Earth is obligated to pledge: “I swear, by my life and my love of it, that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”

If “Atlas Shrugged” is the Bible (although it’s not; the Bible is shorter), then John Galt’s oath is the Ten Commandments. It is engraved in the heart of every Objectivist, tattooed on the arm of many of them, printed on T-shirts, coffee mugs, caps, posters – on anything that can be sold for a few bucks, for the egoistical benefit of buyer and seller.

Within a few years of Rand’s death, the movement she founded faced a crisis that revolved around a question usually reserved for discourse surrounding religious cults: Is Objectivism a complete, hermetically sealed doctrine – as Peikoff and the vast majority of her followers maintained – or is it an elastic philosophy that can still be developed, as a no-less loyal Randist, David Kelley, thought? For a few thousands of die-hard Objectivists, this was not merely a theoretical matter; old friends turned their back on each other, families were torn apart.

In 1985, Peikoff, the leader of the orthodox majority faction of the movement remaining after Rand’s death, established the Ayn Rand Institute, a research body that would disseminate standard Objectivism, the type that is permissible and desirable to contemplate by day and by night, but in which not even a comma can be changed. The institute’s declared goal is to “spearhead a cultural renaissance that will reverse the anti-reason, anti-individualism, anti-freedom, anti-capitalist trends in today’s culture.”

According to Rand, we should take pride in, and feel blessed by, pure

capitalism – the sort that is fueled by uncompromising rational egoism.

In leftist eyes, this constitutes a paradox. After all, every social democrat knows that the 1980s marked the awakening of neoliberalism, the “swinish capitalism” with which economist Milton Friedman cultivated leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Well, you’re making Rand laugh: Friedman’s insistence on viewing economics as a science detached from philosophy made him, in her eyes, a “miserable eclectic” and “an enemy of Objectivism.” Redemption would not come from pretend capitalists.

Meeting the faithful

I decided to pay a visit to the Ayn Rand Institute in Southern California for two reasons: to meet Rand herself through her private archive there, and to meet the faithful of her cult of followers who, like her, are known among their enemies as mysterious, rigid, dogmatic, humorless, socially challenged individuals who are unable to express human affection – people who admire humankind but hate human beings. It’s not surprising that many of them, so it’s said, have chosen, like Rand herself, not to have children.

The headquarters of the Ayn Rand cult is located in the city of Irvine, one of the least touristy places within the greater Los Angeles area. It’s morning, the streets are utterly empty, the few paved sidewalks look as sterile as a computer simulation of some future real estate project. In another two months, the emptiness would be due to the area’s closure, following the advent of the coronavirus pandemic.

|

| Lee Lawrie's statue of the Greek titan Atlas, the inspiration for Ayn Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged. | Credit: Michael Greene |

I walk to the address I’ve been given, on the way memorizing John Galt’s oath from my iPhone, in case officers of the order ask me to recite it. I stand below their premises. Not a bewitched fortress or a dark monastery, but a plain 10-story office building; there are a hundred like it in Ramat Hahayal or the Ra’anana industrial zone, in Israel.

At the entrance is a small man-made pond with ducks paddling about on it. Just before I enter the lobby, one of them fixes round, warning eyes on me, and I can’t help thinking that this duck was once a person who arranged to visit here, did not properly follow the order’s ritual rules and paid for it by being cursed for all eternity. What will happen if they ask me whether I’m an Objectivist? Is it the custom to say “good morning” there, or does that greeting attest to moral failure, an irrational act that exercises the vocal cords for the sake of taking an interest in the happiness of a person who is not me? Is it okay to look them in the eyes?

I press the doorbell on the sixth floor. As I will infer afterward, as I wait for long seconds at the entrance, members of the order, proficient in the “stranger at the door” drill, doff their robes, remove the stuffed heads of leftists that normally hang on the walls, and try to create the appearance of an innocent office within the space there. Steps are heard approaching from inside. The door opens, and facing me is the gatekeeper of the order – a man on the brink of retirement age, no longer wearing the robe, wearing a broad smile and overt silence. I introduce myself hesitantly. “Come in,” he whispers, “we’ve been waiting for you.”

The Ayn Rand Institute – the control center of the world Objectivist cult – looks like a medium-sized accountant’s office. In the anteroom, behind a rope barrier similar to those found in banks, is the original wooden desk on which Rand wrote her books and articles. The desk was built by her husband, the actor and painter Frank O’Connor. It’s a very heavy desk, recalling a medieval surgical table. Only God knows how many social democrats have been tortured on it by electric shock since it was brought here.

The cult extolled radical individualism, consisting of people whose philosophical, political,

cultural, aesthetic, cinematic, literary and musical tastes are absolutely identical.

The gatekeeper entrusts me to Jennifer, the archive’s director. She shows me around the office and introduces me to the dramatis personae, each of whom is nicer and friendlier than the last. Then she takes me to the kitchenette. There are three boxes of cookies on the counter. I look for a name sticker on them, stating which of the people in the office is the exclusive legal and moral owner of said property, bought with his money, with the egoistic intent of benefiting his own material and spiritual condition.

“The cookies belong to everyone, feel free to have some,” Jennifer says. “To everyone?” I give her a suspicious look. “What do you mean, ‘to everyone’?”

“There’s coffee here, too,” she adds, pointing to a shared machine, with shared capsules in a drawer with shared cups, which can be washed in the shared sink. There’s also a shared refrigerator and a shared microwave machine for the office staff. These people have decided to play mind games with me.

For quite a few days, I arrive at the office in the morning and leave when it’s dark. My many hours at the institute are spent alone, at the table in the archive library, as Jennifer, displaying endless devotion, plies me with dozens of numbered cartons that contain innumerable fan letters to Rand, letters she wrote castigating rivals from right and left, invitations to lectures, telegrams she sent, notes she scribbled, original handwritten drafts of her literary works.

There’s also a sensational find: a receipt bearing her name, from February 1940, for a $25 donation to the people of Finland to help them repel the Red Army’s invasion. In the language of scoop hunters on Twitter: “Boom!” And in the language of biographers: To take revenge on the communists for what they did to her and her family in 1917, she was ready, in a moment of weakness, to do something for others. Poor woman, she [had] lost it for a moment.

|

| The entrance to the Ayn Rand Institute. Looks like a mid-sized accountant’s office. | Credit: Itay Meirson |

••••••

During the many long days I spend there, not once do I catch the members of the order stepping out of the humane and people-loving guise they’d donned in my honor. Not when I go down to have lunch with them, nor when some of them engage me in friendly chitchat. One is the director of the Ayn Rand Institute – yes, we can stop calling it an “order” now – a particularly friendly Israeli fellow and a marvelous conversationalist named Tal Tsfany. One fine day in 2018, after making his fortune in high-tech, Tsfany decided to stop advancing his own interests in order to try to get other people to advance their own.

The Israeli connection to the Objectivist movement is not a coincidental one. First, the CEO of the institute from 2000 to 2017 was also a former Israeli, Yaron Brook, who is apparently the most successful spokesperson for Randism in this century, together with the aged Peikoff.

Second, and more important, in regard to the connection with Israel – this time regarding its conflict with the Arabs – the Objectivist movement espouses a position to the right of the most hawkish members of the Zionist camp. Certainly, the Objectionists say, Israel is far from being an Objectivist paragon: It has a centralist, union-driven economy; its nationalism is suffused with primitive religious collectivism. But when Israel is seen in light of the backward, oppressive, anti-rational dictatorships that surround and want to eradicate it – it is nothing but a beacon of light of individual freedom in a dark cave. In Rand’s words, “When you have civilized men fighting savages, you support the civilized men, no matter who they are.” Let the IDF win – but in a rational way, of course.

Intellectuals needed

Still, it wasn’t my Israeliness that prompted the folks at the institute to be so cordial. They’re nice to anyone who shows an interest in them, to anyone who displays sincere curiosity. The Objectivist movement takes seriously the Randian imperative, according to which all the ills of the West (kowtowing to the weak, apologizing for the achievements of capitalism, hatred of the good for being good) are the result of a philosophical flaw, hence it follows that the correction must be made on a philosophical basis. Capitalism, in their view, is too important to be left to ignorant boors like Donald Trump or Israel’s Nir Barkat, who preach a free market without understanding either what a market is or what free means.

Accordingly, what the Objectivists need desperately are more intellectuals who will adopt their precepts lock, stock and barrel. And because no sensible intellectual will stick the tip of his nose into a cult, they are vigorously dissociating themselves from that appellation – and the truth is that they are indeed far less insular and purist than they were two or three decades ago.

Just before I take my leave of the institute’s staff, Jennifer gives me a box of surplus books and invites me to choose one as a gift. I’m not even surprised. See you later, I tell them, knowing that they really are nice people, almost normative, that it’s great to talk to them about subjects that don’t occupy any other institute, and that they are really and truly concerned about the future of the human race, which is shackled by an altruistic ethos that threatens to thrust it back into the dark ages.

Faithful to the Randian spirit, I spend the day that remains before my flight home egoistically and rationally wasting a few dollars at the Universal Studios park. I clear my mind by going on the Harry Potter roller coaster. I have a regular habit on roller coasters: During the scariest part, when the G-force forces my lungs into my gut, I start thinking about epistemology.

Faithful to the Randian spirit, I spend the day that remains before my flight home egoistically and rationally wasting a few dollars at the Universal Studios park. I clear my mind by going on the Harry Potter roller coaster. I have a regular habit on roller coasters: During the scariest part, when the G-force forces my lungs into my gut, I start thinking about epistemology.

Nathaniel Branden – Rand’s pupil, lover and colleague, whom she eventually cast off – claimed that anyone who truly understands her is bound to agree with her. He was wrong. But what’s great about Rand is that everyone is wrong about her. Her ardent admirers see her as the greatest philosopher since Aristotle (she’s not); conservatives accuse her of demanding to banish belief in God from the world (she didn’t; she only claimed, and rightly, that if everyone were to behave rationally, that belief would uproot itself); leftists maintain that she is a lightweight philosopher (she’s not; her Objectivism is fully grounded and consistent, apart from a few minor internal contradictions, which are also debatable). Ayn Rand should be evaluated, and sometimes strongly criticized, for the philosopher she is – not for the philosopher she is not.

The tendency of Rand’s haters is to see her philosophy as a package deal. In this, ironically, they are no different from followers of her cult. But when objectivism is divided into its four tiers, it becomes more useful. It makes no different whether you’re Bernie Sanders or Stanley Fischer, Shelly Yacimovich or Nehemia Shtrasler, the CEO of the NGO Latet (To Give) or the chairman of Lakahat (To Take): If you understand Ayn Rand, you will become a better capitalist, social democrat or communist. Her Objectivism is an ideology-sharpener that should belong in every pencil case. Indeed, every pencil you put into it will come out better honed than when it went in. Even today. Especially today.

Itay Meirson is a doctoral student at The Zvi Yavetz School of Historical Studies, Tel Aviv University, where he’s studying the intellectual history of the American right.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

The System that Wasn’t There: Ayn Rand’s Failed Philosophy (and why it matters)

https://www.rotman.uwo.ca/the-system-that-wasnt-there-ayn-rands-failed-philosophy-and-why-it-matters/

by Nicholas McGinnis

August 25th, 2012 | Philosophy of Ethics

1.

“I grew up reading Ayn Rand and it taught me quite a bit about who I am and what my value systems are, and what my beliefs are. It’s inspired me so much that it’s required reading in my office for all my interns and my staff.” - Senator Paul Rand of the conservative right

That’s Paul Ryan, Republican vice-presidential candidate, in a 2005 speech delivered at The Atlas Society–one of many lavishly funded organizations devoted to spreading the thought and philosophy of Ayn Rand (he’s since distanced himself).

|

| fig. 2. To hell with your ‘flu shots,’ parasites |

The fantastically rich find in Rand’s celebration of individual achievement a kindred spirit, and support her work with pecuniary enthusiasm: in 1999, McGill University turned down a million-dollar endowment from wealthy businessman Gilles Tremblay, who had given the money in the hopes of creating a chair dedicated to the the study of her work. Then-president Bernard Shapiro commented that “we can’t just sell our souls just for the sake of being richer,” hopefully aware of the irony: "what else is there but getting richer?" Rand literally ends her most famous novel, Atlas Shrugged, with the dollar sign replacing the sign of the cross, traced in the air–indicating the dawn of a new, bold, daringly sophomoric era.

Rand’s books have sold in the millions, never quite losing steam in the half-century since publication. A now-infamous Library of Congress survey placed Atlas Shrugged as the second-most influential book in America, trailing only the Bible–a dubious pairing, perhaps, given Rand’s militant atheism, but one that indeed captures the uneasy tension of contemporary America: the celebrated Protestant ethic versus the spirit of capitalism.

Despite her popular appeal, perennially best-selling books, and the breathless testimonial of politicians, actors and businessmen–Ryan is scarcely alone in his praise–professional academics almost universally disdain Rand. An online poll by widely-read philosophy professor and blogger Brian Leiter had Ayn Rand elected the one thinker who “brings the most disrepute on to our discipline by being associated with it,” by a landslide. She is almost never taught in classrooms. Her name elicits jeers and funny, exasperated tales of fierce, bright undergraduates under her spell arguing her case for hours on end.

This near-unanimous rejection has led to some remarkably uncharitable, and bizarre, attempts to explain away the lack of academic interest: in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) entry on Rand, its authors write that “her advocacy of a minimal state with the sole function of protecting negative individual rights is contrary to the welfare statism of most academics,” claiming outright that the overwhelming majority of professional philosophers and political theorists have been simply unable to fairly evaluate her work because of the biasing factor of their prior political commitments.

Somehow the same ‘welfare statism’ of academics has not prevented the close study of Robert Nozick’s landmark Anarchy, State and Utopia, a sophisticated libertarian text that mounts an original, and far more effective, argument against redistributive policies. Apart from John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, there is perhaps no more commonly-assigned book in undergraduate political philosophy classes.

Surely there must be some other reason for Rand’s academic neglect. The authors of the SEP entry do go on to suggest an additional number of largely psychological hypotheses having to do with Rand’s dogmatic tone, cult-like following, and emphasis on popular fiction–never entertaining the possibility that professional philosophers think her work is, quite simply, of poor quality. Objectively, ahem, speaking.

2.

|

fig. 3. Immanuel Kant: “the preeminent good which we call moral …

is only possible in a rational being.” Oops.

|

I am primarily the creator of a new code of morality which has so far been believed impossible, namely a morality not based on faith, not on arbitrary whim, not on emotion, not on arbitrary edict, mystical or social, but on reason; a morality that can be proved by means of logic which can be demonstrated to be true and necessary.

Now may I define what my morality is? Since man’s mind is his basic means of survival […] he has to hold reason as an absolute, by which I mean that he has to hold reason as his only guide to action, and that he must live by the independent judgment of his own mind; ... that his highest moral purpose is the achievement of his own happiness […] that each man must live as an end in himself, and follow his own rational self-interest.

The practical, political conclusions to be drawn from this ‘morality’ are surprisingly specific: a minimal government, for instance, which enforces no minimum wage law, operates no schools, collects no taxes, and merely enforces contracts in an economy that is otherwise entirely laissez-faire. Rational individuals do not come together to create a universal health insurance system in the process of seeking ‘happiness’. They do not pass laws restricting what age a child can work.

|

| fig. 4. Rationality at work. |

This is unfortunate, because her philosophy attempts to form a coherent system, and these higher-order political views are the direct result of foundational assumptions in metaphysics and logic (and a series of complex derivations from these). This is one case where an opinion on the possibility of a priori knowledge could mean the difference between a school breakfast program and a hungry child.

Now there are two ways to approach Objectivism: first, and most commonly, we may tackle her edifying fiction, which portrays Manichean conflicts between heroic, intelligent ‘producers’ and parasitic ‘looters.’ The latter, mainly by force of numbers and all the vile raiments of democracy, get in the way of the former: they do not understand that they depend, utterly, on these rarefied ubermenschen, who, of course, ultimately triumph. Given the stark morality of the novels, everyone who reads them in a positive light cast themselves quite naturally as noble producers, and certainly not parasites, which, given Rand’s popularity, means we are a society absolutely replete with noble, heroic, rugged geniuses.

Well-meaning readers are taken in by her grandiose, if somewhat turgid, presentation of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute (Atlas Shrugged).

The values propounded in her work many find stirring and true. To contest Rand, to the true believer, is to besmirch rationality itself, to prize the unremarkable ‘collective’ over the individual, to shrug at excellence, and–from jealousy, or some other base instinct–to hate and undermine one’s betters and undeservedly demand what is theirs.

The other way in is via her ‘system’ of philosophy: resolutely materialistic, godless, and rationalistic. It proceeds largely from a set of basic axioms (‘existence’, ‘identity’, ‘consciousness’) and derives a more-or-less comprehensive set of metaphysical, epistemological and ethical views. Here we have a complicated internal jargon (which resists assimilation into the analytic vernacular) and a set of post-Randian writers–Peikoff, Kelley, and others–who have fleshed out and expanded her thought into something like a philosophical system in the traditional sense, the kind of thing that has been largely abandoned in contemporary academic philosophy. One can get a sense of the ‘system’ from a glance at the wikipedia page: there are any number of dubious inferences made, most remarkably from ‘existence’ to ‘identity’ to something like conceptual necessity (and thence to causality itself, defined as the “principle of identity applied to action”–possibly the most cringe-worthy explanation of causality to ever be presented seriously: in effect, we are told that things do as they do because they are as they are.)

From axiomatic bases the edifice is built: existence exists and is characterized by identity, which is populated by conscious beings, who must use reason to survive as individuals, and the dictates of reason force us to admit that rational self-interest is the only metaphysically coherent way forward, logically implying capitalism and free markets. To deny this is to deny that A is A.

3.

|

| "I think she’s [Rand] one of the greatest people of all time. Ultimately, in philosophy, she’s going to be one of the giants. I mean, she’ll be up there with Plato and Aristotle." |

That’s Dr. Yaron Brook, who holds a PhD in Finance from the University of Texas at Austin. This provocative quote is culled from a recent interview in which he asserted that we are headed for a new dark ages unless we heed Rand’s wisdom. If we do not, “the next renaissance will begin when her books are rediscovered after 1,000 years of darkness.”

Brook is the director of the Ayn Rand Institute, the largest Objectivist organization, with a budget in the millions and political links to the Tea Party movement. [Question: Do they have links to Ross Perot, the Texas Oil Tycoon? and Independent nominee for President?]

|

| fig 5. The enlightened Dr. Yaron Brooks: "I would like to see the United States turn Fallujah into dust, and tell the Iraqis: If you’re going to continue to support the insurgents you will not have homes, you will not have schools, you will not have mosques." |

Rand’s extreme self-regard was mirrored in her friends and followers. Former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan–a member of Ayn Rand’s tightly-knit inner circle–only recently, and reluctantly, acknowledged that there may be ‘flaws’ in Rand’s ideology of self-interest. But in the 1960s, he was writing for objectivist newsletters, and praised Rand for decades afterwards: “talking to Rand was like starting a game of chess thinking I was good, and suddenly finding myself in checkmate,” he said. In a 1957 letter to the editor prompted by a dismissive review of Atlas Shrugged, he wrote:

"Atlas Shrugged’ is a celebration of life and happiness. Justice is unrelenting. Creative individuals and undeviating purpose and rationality achieve joy and fulfillment. Parasites who persistently avoid either purpose or reason perish as they should."

One wonders at the type of celebration of ‘life’ that centers around satisfied joy at the perishing of so-called ‘parasites.’ A boldly totalitarian discourse of justified elimination, produced a scant dozen years after the end of the second world war. It is a tradition upheld by contemporary Randians: Brooks has called for unrestricted, murderous warfare in Iraq (see above); Leonard Peikoff, who originally founded the Ayn Rand Institute, calls for the “immediate end” of “terrorist states” such as Iran, not ruling out nuclear weapons, and this “regardless of the countless innocents caught in the line of fire.”

Admiration for Rand can be found in strange places. Actors from Brad Pitt to Farrah Fawcett have effused praise as well. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas allegedly makes his clerks watch the 1949 film version of The Fountainhead. But the definitive statements belongs to her lover and confidante Nathaniel Branden (indeed, Rand’s heir apparent until a fractious and unsavoury dispute over his termination of their affair). He recalls writing, in all seriousness, that

Ayn Rand is the greatest human being who has ever lived. Atlas Shrugged is the greatest human achievement in the history of the world. Ayn Rand, by virtue of her philosophical genius, is the supreme arbiter of any issue pertaining to what is rational, moral or appropriate to man’s life on earth.

These were the initial premises presented in Branden’s lecture courses on objectivism, approved and overseen by Rand herself. From this point of view, it is indeed very fortunate for humanity that Rand did not choose to ‘go Galt’ and, like her most famous protagonist, withdraw her genius from us.

4.

|

| fig 6. Soldiers marching in Petrograd, 1917. Rand was twelve. |

Meanwhile, a thriving cottage industry of journalists, essayists, cultural observers and philosophers seem engaged in a one-upmanship contest over who can deride her with the most vicious economy of words possible. George Monbiot says of Rand that her thought “has a fair claim to be the ugliest philosophy the postwar world has produced.” Corey Robin, with a historical flourish, writes that “St. Petersburg in revolt gave us Vladimir Nabokov, Isaiah Berlin and Ayn Rand. The first was a novelist, the second a philosopher. The third was neither but thought she was both.” The late Gore Vidal was scathing even decades ago, writing in 1961 that Rand

"Has a great attraction for simple people who are puzzled by organized society, who object to paying taxes, who dislike the “welfare” state, who feel guilt at the thought of the suffering of others but who would like to harden their hearts […] Ayn Rand’s “philosophy” is nearly perfect in its immorality, which makes the size of her audience all the more ominous and symptomatic."

Criticism has not only come from the left. While Rand’s allure to conservatives is far more pronounced now–despite some lingering misgivings from religious groups–intellectuals on the right despaired of Rand’s growing influence when her books were first published. In the National Review, Whittaker Chambers wrote, in 1957:

"Out of a lifetime of reading, I can recall no other book in which a tone of overriding arrogance was so implacably sustained. Its shrillness is without reprieve. Its dogmatism is without appeal. In addition, the mind which finds this tone natural to it shares other characteristics of its type.

(1) It consistently mistakes raw force for strength, and the rawer the force, the more reverent the posture of the mind before it. (2) It supposes itself to be the bringer of a final revelation. Therefore, resistance to the Message cannot be tolerated because disagreement can never be merely honest, prudent, or just humanly fallible."

This was at a time when many conservative intellectuals saw in the complexity of the world a reason to be trepidant about radical change and wary about the potential for deleterious destabilization it brings, an altogether different form of ‘conservatism’ from that of the present-day marriage of libertarian economics with theological presumption. Chambers rightly saw in Rand a dangerous radical, one who glosses over complexity in her desire to derive political prescription from first principles, an anti-conservative writer par excellence advocating a radically different society:

"[Atlas Shrugged] is essentially a political book. And here begins mischief. Systems of philosophic materialism, so long as they merely circle outside this world’s atmosphere, matter little to most of us. The trouble is that they keep coming down to earth. It is when a system of materialist ideas presumes to give positive answers to real problems of our real life that mischief starts. In an age like ours, in which a highly complex technological society is everywhere in a high state of instability, such answers, however philosophic, translate quickly into political realities. And in the degree to which problems of complexity and instability are most bewildering to masses of men, a temptation sets in to let some species of Big Brother solve and supervise them."

William F. Buckley, who helped define modern American conservatism by launching and serving as editor-in-chief of The National Review, specifically published Chambers’ critique (and others like it) to purge Rand from conservatism–writing that “her desiccated philosophy’s conclusive incompatibility with the conservative’s emphasis on transcendence, intellectual and moral” meant it was unworthy of the noble tradition of conservative politics, and to be cast out with the Birchers, anti-semites, and white supremacists.

The difference of opinion over the value of Rand’s work could not be more stark. One is hard-pressed to find a ‘moderate’ who finds in Rand some modest value or would characterize her as a decent, or simply good, thinker. She is either genius or a fraud; either a first-rate, world-historical intellectual or a hack writer who appeals to the worst in people by pointing to their wounded self-worth and telling them they are great (“To say “I love you” one must first be able to say the “I” ”, she wrote in The Fountainhead, sounding more like Dr. Phil and less like the heir to Aristotle).

This polarizing effect is remarkable. It is partially a function of the reach of her work: far worse things have been expressed than those ideas contained in Rand’s novels, but almost none have had the impact (ten million grenades handed out on street-corners do more damage than an atom bomb left sitting on a shelf). But the virulence is also a reaction to the breathless fanaticism of her converts, hyperbole matched to hyperbole, in the full knowledge that derision is often more effective than argument in inoculating the undecided.

The difference of opinion over the value of Rand’s work could not be more stark. One is hard-pressed to find a ‘moderate’ who finds in Rand some modest value or would characterize her as a decent, or simply good, thinker. She is either genius or a fraud; either a first-rate, world-historical intellectual or a hack writer who appeals to the worst in people by pointing to their wounded self-worth and telling them they are great (“To say “I love you” one must first be able to say the “I” ”, she wrote in The Fountainhead, sounding more like Dr. Phil and less like the heir to Aristotle).

This polarizing effect is remarkable. It is partially a function of the reach of her work: far worse things have been expressed than those ideas contained in Rand’s novels, but almost none have had the impact (ten million grenades handed out on street-corners do more damage than an atom bomb left sitting on a shelf). But the virulence is also a reaction to the breathless fanaticism of her converts, hyperbole matched to hyperbole, in the full knowledge that derision is often more effective than argument in inoculating the undecided.

|

| fig. 7. Greatest. Human. Ever |

It is true that Rand’s opponents in popular media often focus on her personal life–her exile from Russia, her ‘rational’ and tawdry affair with Branden, her Hollywood roots, her censorious soirees (hilariously parodied in Rothbard’s one-act ‘play’ Mozart was a Red)–and only mention her ethics and philosophy to disparage the conclusions reached. It appears self-evident that all this talk of ‘existence exists’ as applied to public policy is nonsense, so it suffices to trot out the absurdities of ‘ethical egoism’ and the case is settled.

Rand’s proponents, particularly those of an intellectual bent, find in such ‘evasions’ a confirmation that they hold a rationally acquired set of truths: otherwise, critics of Rand would be able to take on the system, rather than engage in ad hominem or demonstrate emotionally-clouded dislike of her inescapable conclusions (proof positive of their own unreason). Even those who have only felt from the novels an intuitive, undeniable pull know that beneath the pulp of Roark, Taggart and Galt lies a profound set of philosophical doctrines that the high priests can always ably defend and no critic dares touch.

5.

|

| fig. 8. Robert Nozick–Another great, though lesser, human |

One of the few academic philosophers to take Rand seriously enough to bother with a critique was our erstwhile libertarian friend Robert Nozick. His short article On the Randian Argument proposes to examine the alleged ‘moral foundations of capitalism’ provided by her system. Almost immediately it devolves in dialectical castigation, with Nozick taking Rand to task for lacking clarity, for failing to adequately support her premises, for drawing unsupported conclusions, and for baldly stating controversial theses as if they were self-evident facts. From the very first, he writes that “I would most like to set out the argument as a deductive argument and then examine the premises. Unfortunately, it is not clear (to me) exactly what the argument is.” His reconstruction is a marvel of patience and charity–combined with lacerating criticism. He sums up the argument:

(1) Only living beings have values with a point.

(2) Therefore, life itself is a value to a living being which has it.

(3) Therefore, life, as a rational person, is a value to the person whose life it is.

(4) Therefore, [there is] “some principle about interpersonal behaviour and rights and purposes.”

The argument is, at some length, considered and demolished. Two quick examples suffice (the interested reader may consult the piece).

Upon examining the premise that ‘life’ is a necessary precondition for the existence of value and is, therefore, a value itself (2), Nozick dryly comments that

"one cannot reach the conclusion that life itself is a value merely by conjoining together many sentences containing the world ‘value’ and ‘life’ or ‘alive’ and hoping that, by some process of association and mixture, this new connection will arise."

The problem is that Rand, Nozick says, does not consider other value-forming concepts during the course of her transcendental argument and has no means to rule them out:

"Cannot content be given to should-statements by … any one of a vast number of other dimensions or possible goals? … it is puzzling why it is claimed that only against a background in which life is (assumed to be) a value, can should-statements be given a sense. It might, of course, be argued, that only against this background can should-statements be given their correct sense, but we have seen no argument for this claim."

Puzzling indeed: certainly alternatives are possible. And it is not that these alternatives do not ‘value life’ themselves–of course they do, derivatively. Rand’s claim is that valuing life must be foundational, but, apart from some intuitive appeal, we are never told why that should be.

More troublesome yet is the leap from premises (1-3) to the vague principles of (4), which Nozick claims involves a number of dubious assumptions–not the least of which is a principle requiring there be no “objective conflicts of interests between persons”, ever. Surely this is too strong: even the Gods are known to quarrel.

|

| fig 8. Mt. Olympus |

"For many, the first time they encounter a libertarian view saying that a rational life (with individual rights) is possible and justified is in the writings of Miss Rand, and their finding such a view attractive, right, etc., can easily lead them to think that the particular arguments Miss Rand offers for the view are conclusive are adequate."

This is likely correct. Nozick, a libertarian political philosopher himself, is sympathetic to the some of the conclusions Rand draws, but finds himself unable to endorse the arguments presented. The ‘moral’ case for capitalism flounders in a morass of unjustified assumptions and leaps of inference, glossed over by a tone of material certainty. It seems plausible only to the extent that we appreciate her peculiar moral sensibility.

Her ‘metaphysics’ fare no better. This is all the more damning, since her value theory is meant to follow directly from her basic, indubitable axioms: identity, existence, and consciousness.

The abuses of ‘identity’ (“A is A”) have been singled out for particular criticism. Sidney Hook, writing in 1961, notes that:

The extraordinary virtues Miss Rand finds in the law that A is A suggests that she is unaware that logical principles by themselves can test only consistency. They cannot establish truth […] Swearing fidelity to Aristotle, Miss Rand claims to deduce not only matters of fact from logic but, with as little warrant, ethical rules and economic truths as well. As she understands them, the laws of logic license her in proclaiming that “existence exists,” which is very much like saying that the law of gravitation is heavy and the formula of sugar sweet.

The problem, in a nutshell, is that logical principles are devoid of genuine empirical content. One cannot derive particular facts from ‘A is A’ any more than one could conjure a slice of pizza from the Pythagorean theorem. Tautologies are meant to be vacuous. (Certainly, at least, public education is not a logical contradiction the same way a married bachelor, or a four-sided triangle, is.)

Logical technicalities aside, it is worth noting that the most important philosopher in the West since Aristotle has no mathematical or logical philosophy to speak of. Rand was writing in the immediate aftermath of the most fertile period of logical and mathematical development in human history. Her emphasis on ‘logic’ and the indubitable inevitability of her conclusions is made in the shadow of Frege, the set-theoretic paradoxes, and the Principia; of the debate over intuitionism, of the incompleteness proof and of the results of Tarsky, Church, Alonzo; and just at the dawn of paraconsistent logic (which rejects, inter alia, that it is always true that A is A).

|

| fig 9. Kurt Friedrich Gödel, April 28, 1906 |

Indeed the crisis in the foundations of mathematics, the work of Tarski on truth, the rejection of the law of excluded middle by Brouwer and his followers, Gödel’s proofs–the list could be multiplied–had no effect on her, if she was even aware of any of it. The Atlas Society’s guide to objectivism candidly admits this lacuna, in its entry on the topic of the philosophy of mathematics:

Ayn Rand’s identification of the nature of universals and her analysis of the process of abstraction have much to contribute to the philosophy of mathematics. There is, however, no Objectivist literature on this topic.

Still, the reader will be glad to hear that the problem of universals has been solved, along with the processes that underpin conceptual abstraction. For a philosopher who prized logic, she remained utterly ignorant of it until her death, and some of her most ardent followers are determined to remain so themselves: Peikoff disparages all non-Aristotelian logic as “inherently dishonest […] an explicit rebellion against reason and reality (and, therefore, against man and values).”

Nozick, again, is perfectly clear on the logical issue: Rand is wrong. But it is not only that Rand uses strictly logical principles to derive ethical and political conclusions, which simply cannot happen, but the means by which she goes about the deduction–should we be so indulgent to permit it—is itself a strange wealth of confusion and error:

The followers of Rand, for example, treat “A is A” not just as “everything is identical to itself” but as a kind of statement about essences and the limits of things. “A is A, and it can’t be anything else, and once it’s A today, it can’t change its spots tomorrow.” Now, that doesn’t follow. I mean, from the law of identity, nothing follows about limitations on change. The weather is identical to itself but it’s changing all the time. The use that’s made by people in the Randian tradition of this principle of logic that everything is identical to itself to place limits on what the future behavior of things can be, or on the future nature of current things, is completely unjustified so far as I can see; it’s illegitimate.

These ‘illegitimate uses’ are nothing short of extraordinary: John Galt, in Atlas Shrugged–Rand’s own mouthpiece, delivering the radio address than encapsulates her philosophical system–claims that:

The source of man’s rights is not divine law or congressional law, but the law of identity. A is A—and Man is Man. Rights are conditions of existence required by man’s nature for his proper survival.

Nozick is exactly right in claiming that Rand leverages the ‘principle of identity’ to all kinds of strange metaphysical purposes, including very contentious–if not outright false–conclusions about essentialism. In Galt’s speech we see “A is A” turned into a statement about the essential ‘nature’ of humankind that carries with it the full logical weight of the putative axiom.

Obviously this doesn’t work: suppose we accept that “A is A” (in particular we are not dialetheists; there is certainly no physical theory which introduces terms that violate identity or non-contradiction, and we know this a priori). This implies nothing about man’s nature. Not even that man has a nature at all. Or that it is fixed. That it cannot be changed, or consciously altered.

Even if man has a ‘nature’ in Rand’s sense, our rational aspects are of a piece with our creative capacities, our imaginative selves, our empathetic abilities, our emotional landscape, our sexual drives: to the extent that Rand’s analysis of human nature as rational is meant to be descriptive of what we actually are, it is surely false.

This is arguably not what she means. We have instead a logically-deduced (yet normative) claim about, say, the rational, conscious apprehension of independent reality being central to ‘man’ and his survival–the only value. (Though, obviously, we don’t in fact survive on reason alone. We couldn’t.) This conclusion, obviously, does not follow, or can be justified by, the principle of identity, nor does it seem a particularly good way of going about determining how to structure human civilization.

This last point is perhaps the most crucial: apart from the details of her argument, and the arcane mysteries that her defenders beckon us enter (to learn about ‘measurement omission’ and the “law of identity applied to action” and other putative solutions to open problems), the most fundamental problem is the methodological assumption that reflection on ‘self-evident’ axioms can generate a host of inescapable moral, political, and economic truths.

6.

Here, then, is a methodological digression, to provide a contrast.

My own politics are generally informed by the desire to live in a ‘good’ society. I’m pretty casual about what ‘good’ means, precisely:

some kind of pluralist satisficing compromise borne of reflective equilibrium. Most of us want a society that is free, genuinely meritocratic, absent egregious social strife and inequality (for basic Rawlsian reasons), with just laws and a representative government and opportunities to develop one’s talents and interests without too much interference.

I like to make arguments based on comparative case studies, analysis of available data, incorporation of sundry pragmatic and practical considerations, various heuristic devices (that are admittedly fallible but reliable), with an eye both the desirability outcomes and the caveat that ends don’t always justify means. It’s not particularly elegant, but it’s reasonable and it works. I make no claim to perfect consistency, have no self-contained system, and pretend to no ultimate, objective answers.

Now contrast this with an axiomatic, a priori approach: where one begins with self-evident truths (or ‘first principles’) and then derives conclusions based on analysis of these: we might take private property as a fundamental concept, for instance, and conclude that we have no duties to the poor. In this we proceed as Hobbes did in his Leviathan, Spinoza in the Ethics, or as Rand does with her “three axioms.” As we saw above, from the assertion of indubitable truths (“existence exists” and so on) we conclude, at the end of a long derivation, that essentially the sole purpose of government is the defense of negative individual rights.

|

| fig. 10. “A is A”; therefore, you must sleep with me. (Yes, Rand basically said this.) |