|

| amazon link |

Alfred North Whitehead was an English mathematician (best known among scientists for his work with his student Bertrand Russell on the Principia Mathematica). But in philosophy and theology, Whitehead is best known as a philosopher whose later work at Harvard included his Process Philosophy and the subsequent development of a Process Theology.

At Harvard, Whitehead supervised Willard van Orman Quine's Ph.D. thesis on the Russell and Whitehead Principia Mathematica. Russell and Quine would become giants in the twentieth-century fields of logical positivism and logical empiricism. Although logical positivism and later analytic language philosophy overwhelmed Whiteheadian "process" thinking in philosophy departments, Whitehead's "process theology" has grown strong in divinity schools around the world. And "Whiteheadian" physicists. impressed by Whitehead's analysis of events in space and time in special relativity as organic "occasions." are prominent in debates about the role of quantum mechanics in consciousness and panpsychism.

Before he came to Harvard, Whitehead wrote three important books while at Trinity College, Cambridge, that put forth his speculative theories on space, time, matter, and energy - An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge (PNK , 1919), The Concept of Nature (CN, 1920), and Principle of Relativity (PoR, 1922),

in PNK Whitehead calls the instantaneous and infinitesimal points of special relativity "event-particles." (p.33) He then says that the events of his theory will include large numbers of "event-particles" because his events are extended in both space and time, an idea he calls "extensive abstraction."(p.101) It is only these finite volumes of space and durations in time that can be perceived or apprehended by an observer. Whitehead is correct that perceivable happenings always involve relatively large numbers of material particles interacting over a period of time, especially biological events.

In CN Whitehead argues against what he calls the "bifurcation of nature" (p.24) that divides the world into the appearance of sense-data (the empiricist's secondary qualities) and the "reality" of the molecules and light energy that are the causes (or primary qualities). For Whitehead there is only one nature. He also argues against the notion of absolute space and time, claiming that the important information is the matter in space and the relative positions of bits of matter.

In PoR Whitehead develops a principle of relativity that differs in significant and erroneous ways from the special and general theories of Einstein's relativity, oddly claiming, for example, that "the ether is an observed character of things observed." (p.5) He developed explanations for shifts in spectroscopic line wavelengths (p.70) and for the splitting of lines that turn out not to have been correct.

Whitehead's "philosophy of organism" analyzes the perception of experience as a continuing series of discrete "events" that are created and destroyed. He goes beyond the simple materialist view of elementary particles interacting in space and time, merely following the laws of classical and quantum mechanics. Beyond the atomic particles and the electromagnetic and gravitational fields, and beyond the conservation laws for energy and momentum, Whitehead sees an "organic" evolutionary process of creation and valuation.

We need to understand what it is exactly that Whitehead thinks is being created and why it can serve as a basis for values. We will argue that Whitehead's process is "organic" because it explains evolution, not merely biological evolution but the cosmic evolution of the galaxies, stars, and planets as well as the creation of all matter from the primordial elementary particles.

In addition to his deep understanding of mathematics, Whitehead may have understood the development of modern physics better than any living philosopher in his day. He saw the greatest invention of the nineteenth century as the invention of the method of invention, namely the scientific method and newly created scientific information, but even more deeply, the means by which novel ideas of all kinds are created.

Whitehead identified four great novel ideas as the new nineteenth-century foundations of physical science, fields, particles, conservation principles, and evolution.

One of the ideas is that of a field of physical activity pervading all space, even where there is an apparent vacuum. This notion had occurred to many people, under many forms. We remember the medieval axiom, nature abhors a vacuum...Thus in the seventies of the last century, some main physical sciences were established on a basis which presupposed the idea of continuity.

The great question for Whitehead as a mathematician - "Is nature continuous or discrete, fields or particles, infinities or a finite number of objects?"On the other hand, the idea of atomicity had been introduced by John Dalton, to complete Lavoisier’s work on the foundation of chemistry. This is the second great notion. Ordinary matter was conceived as atomic: electromagnetic effects were conceived as arising from a continuous field...The notion of matter as atomic has a long history. Democritus and Lucretius will at once occur to your minds. In speaking of these ideas as novel, I merely mean relatively novel,..In the eighteenth century every well-educated man read Lucretius, and entertained ideas about atoms. But John Dalton made them efficient in the stream of science; and in this function of efficiency atomicity was a new idea.The influence of atomicity was not limited to chemistry. The living cell is to biology what the electron and the proton are to physics.

The remaining pair of new ideas to be ascribed to this epoch are both of them connected with the notion of transition or change. They are the doctrine of the conservation of energy, and the doctrine of evolution.

The doctrine of energy has to do with the notion of quantitative permanence underlying change. The doctrine of evolution has to do with the emergence of novel organisms as the outcome of chance. The theory of energy lies in the province of physics. The theory of evolution lies mainly in the province of biology, although it had previously been touched upon by Kant and Laplace in connection with the formation of suns and planets.

Although he starts with the latest science, Whitehead also builds on the ancient problem of the One and the Many, distinctions between the Parmenidean One/Being and the Heraclitean/Democritean flux/many/becoming. He describes the thinking of the mind as a succession of transitions in which many entities become a new unity, a one, after which the new unity/entity becomes part of a new many, etc., etc. He describes this as an organic process.

By starting with the many, Whitehead reads the Platonic divided line from right to left.

| Theories (noesis) Hypotheses (dianoia) | Techniques (pistis) Stories (eikasia) |

Whitehead's preference for organism over mechanism

- emphasizes the importance of time (Hegel, Bergson)

- restores immaterial mind/purpose/telos (Berkeley, Alexander, Lloyd Morgan), and

- recognizes creativity as a process that cannot be understood in deterministic/mechanistic terms.

Whether the mind works as a succession of many-to-one-to-many transitions should be left to modern psychology and neuroscience, but information philosophy has clarified the way in which the mind records and reproduces its experiences, as well as the cosmic creative process behind every new information structure in the universe and any new idea in a mind.

Whitehead's process thinking is influential with some quantum physicists who see quantum waves as possibilities collapsing to become particle actualities. Some so-called Quantum Whiteheadians are panpsychists, who see mind as in all things. Others are panentheists who see everything as a part of God or God in everything.

We can see now that Whitehead actually understood very little of these two pillars of modern physics. He misinterpreted both Albert Einstein's relativity and Niels Bohr's quantum theory. But we can identify two basic elements that he borrowed from them to ground his understanding of the nature of reality as a process.

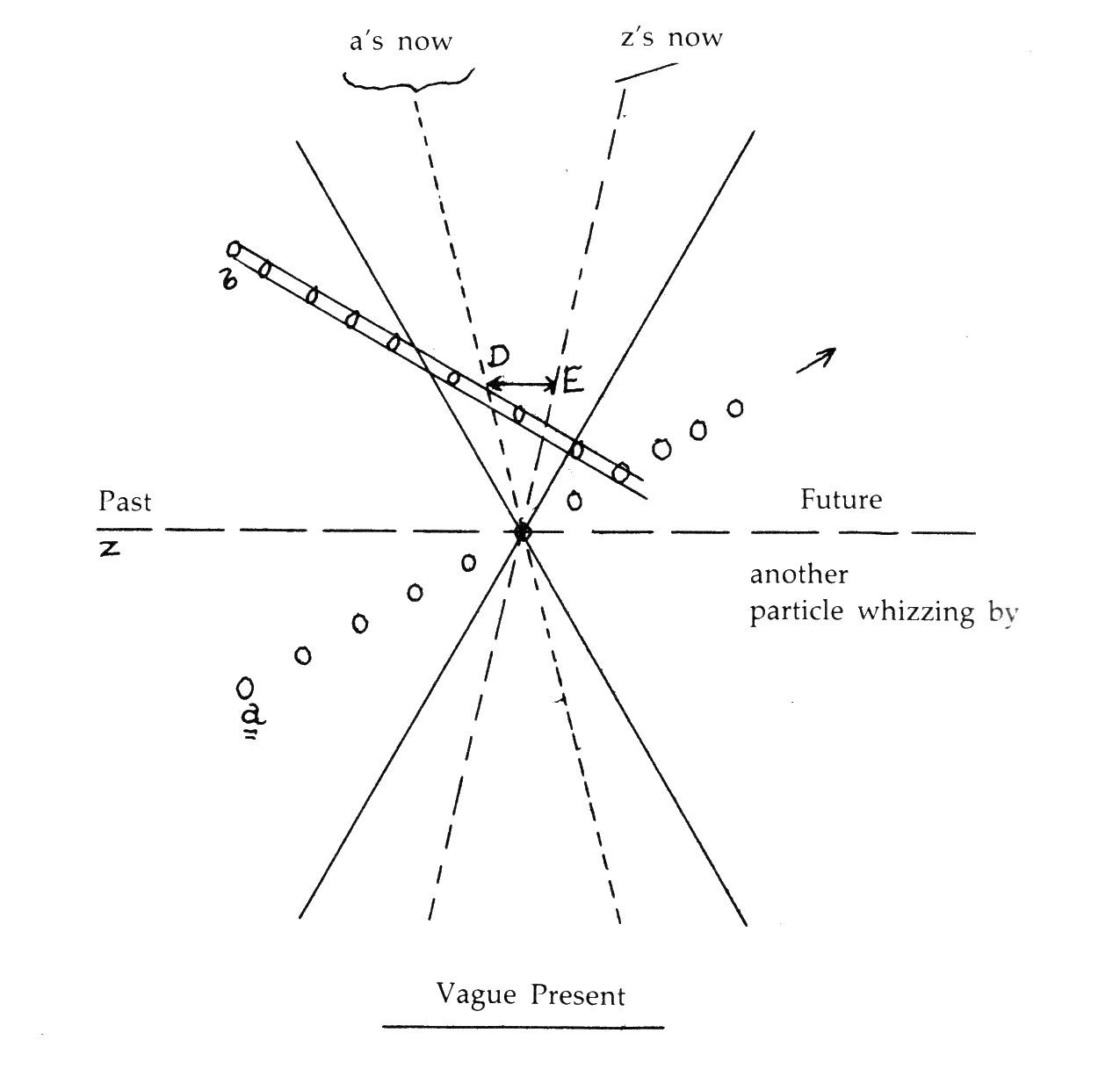

From relativity he took the idea of an event in space and time. His British idealist colleague John McTaggart had formulated two ideas of time. Whitehead likely preferred McTaggart's A series, which is both the common sense view and the metaphysical view now known as presentism. McTaggart's B series is the notion that all times and thus all events, past, present, and future, are all existent and equally real. This is the view of special relativity.

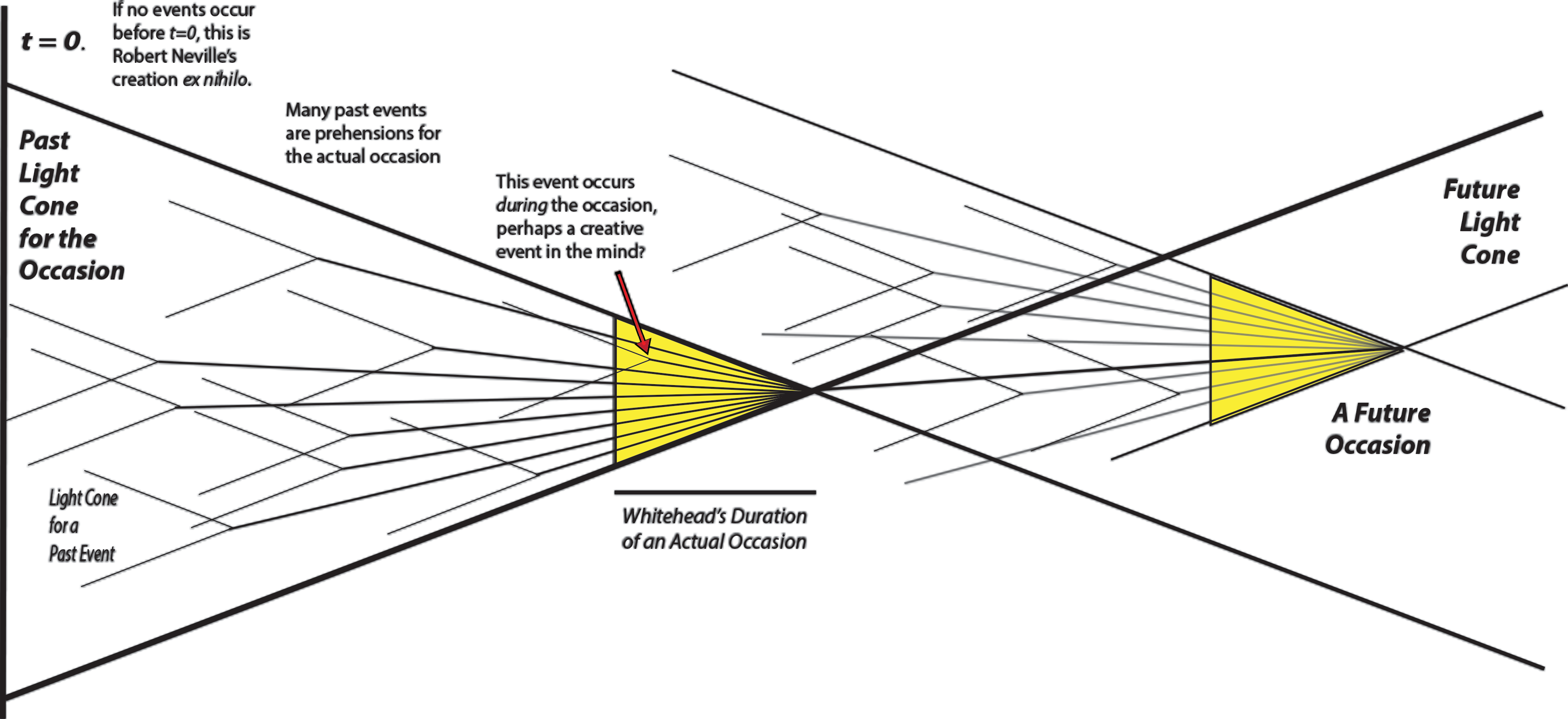

Albert Einstein's four-dimensional space-time was called a "block universe" by Hermann Minkowski. In such a universe causal relations are explained by what Whitehead called "simple location" in space-time. Each event can be caused by something in its past "light cone" andin turn the event has a causal influence over events in its future "light cone.

This is the deterministic Laplacian universe in which a super-intelligence can know the complete past and the single possible future from knowledge of the positions and velocities of all the material particles at the one instant of the present. It was actually Gottfried Leibniz who saw this universe as a consequence of continuous differential equations using his calculus or Isaac Newton's fluxions. Whitehead rejected this reductive view as "scientific materialism."

From quantum mechanics Whitehead took the notion that nature is discontinuous and discrete from Bohr's "old quantum theory" with his "quantum jumps" between discrete energy levels. Perhaps under the influence of Henri Bergson's duration theory of time as discrete intervals, Whitehead analyzed an event, a moment in space-time, stretching it out to a duration or interval between a beginning and an end time, which he later called an "occasion."

From inside that interval, one can look back to perceive the many past events, any or all of which may contribute to this moment seen as a single event, a single cause that will affect many future, as yet unrealized, events.

Which of those past events are selected, and Whitehead's unique contribution is to see that a selection may combine together a large number of past events as causes, introduces an element of novelty and creation. Whitehead's "process" is very far from the simplistic idea of a single causal chain of event-cause-event-cause, etc. And as a temporal process, it is not the familiar Hegelian dialectic of thesis (idea) - antithesis (criticism) - synthesis (Aufhebung) spiraling upward to the ultimate Absolute Idea.

Borrowing from the language of the British empiricists John Locke, David Hume, and especially George Berkeley, Whitehead describes his process as subjective perceptions forming concepts about objects. He views the immediate present subject as perceiving the past events (now simply objects) and freely choosing some of them (he calls this prehending them) to be combined in new ways (he calls this concretion or concrescence - a growing together) to create a new idea or concept (he calls a creature), which immediately falls into the past light cone (he calls this perishing), becoming just one more object. Some of the past many have become a new one, which can join the future many, converging onto future events that will again each become one.

In his Lowell Lectures of 1925 (which became the classic book Science and the Modern World), Whitehead railed against "scientific materialism" and the deterministic claims of science. In his preface, he describes his goal,

The present book embodies a study of some aspects of Western culture during the past three centuries, in so far as it has been influenced by the development of science. This study has been guided by the conviction that the mentality of an epoch springs from the view of the world which is, in fact, dominant in the educated sections of the communities in question...Philosophy, in one of its functions, is the critic of cosmologies. It is its function to harmonise, re-fashion, and justify divergent intuitions as to the nature of things. It has to insist on the scrutiny of the ultimate ideas, and on the retention of the whole of the evidence in shaping our cosmological scheme. Its business is to render explicit, and—so far as may be—efficient, a process which otherwise is unconsciously performed without rational tests.

Bearing this in mind, I have avoided the introduction of a variety of abstruse detail respecting scientific advance. What is wanted, and what I have striven after, is a sympathetic study of main ideas as seen from the inside. If my view of the function of philosophy is correct, it is the most effective of all the intellectual pursuits. It builds cathedrals before the workmen have moved a stone, and it destroys them before the elements have worn down their arches. It is the architect of the buildings of the spirit, and it is also their solvent: —and the spiritual precedes the material. Philosophy works slowly. Thoughts lie dormant for ages; and then, almost suddenly as it were, mankind finds that they have embodied themselves in institutions.

Whitehead proceeds to build a new philosophy of the spirit and mind that bases nature on the concept of organism, and not upon the concept of matter. Like Plato (to whom Whitehead is perhaps the most famous footnote), Whitehead privileges form over content, the ideal over the material world. Although he claims to avoid the "abstruse detail" about science, he elaborates a complex and often obscure vocabulary of terms to describe the process of thought that creates the eternal ideas, based on the mind's perception of experiences. Whitehead's writing style is dense, with mesmerizing repetitive variations on his basic themes, like G.W.F.Hegel, whose philosophy Whitehead learned from the equally verbose British idealists F.H.Bradley and John McTaggart.

Like the empiricist George Berkeley who denied the material world to stress the immaterial ideas that we create through our perceptions, Whitehead's philosophy of organism invents a dense language to describe and analyze the process of thinking. Where "esse est percipi," to be is to be perceived, was Berkeley's motto, we might say Whitehead believed that his dialectical analysis of the "process" of perception and conception will reveal the true reality as the sum of our experiences. For Whitehead and for Berkeley, the process of a subject perceiving objects and thinking with concepts is reality.

Whitehead calls for a wider field of abstraction than that used in the scientific field of thought, we should have in our minds a more concrete (sic) analysis of our concepts, which will stand nearer to the "complete concreteness of our intuitive experience." Whitehead's notions of concrete, concretion, even his later concrescence may blur the usual mapping of the ideal/material dualism onto the abstract/concrete.

Whitehead's call for wider "thinking about thinking" as an organic process extends "ideas" from the mind of God to the interactions of elementary particles as enduring "patterns" over time. He also introduces "eternal objects" (perhaps the Platonic Forms?) that are outside of time.

Such an analysis should find itself a niche for the concepts of matter and spirit, as abstractions in terms of which much of our physical experience can be interpreted. It is in the search for this wider basis for scientific thought that Berkeley is so important. He launched his criticism shortly after the schools of Newton and Locke had completed their work, and laid his finger exactly on the weak spots which they had left. I do not propose to consider either the subjective idealism which has been derived from him, or the schools of development which trace their descent from Hume and Kant respectively. My point will be that—whatever the final metaphysics you may adopt—there is another line of development embedded in Berkeley, pointing to the analysis which we are in search of. Berkeley overlooked it, partly by reason of the over-intellectualism of philosophers, and partly by his haste to have recourse to an idealism with its objectivity grounded in the mind of God. You will remember that I have already stated that the key of the problem lies in the notion of simple location. Berkeley, in effect, criticises this notion.

Whitehead quotes Francis Bacon's Natural History as claiming that "all bodies whatsoever, though they have no sense, yet they have perception". He then replaces standard terms like perception with variant terms that do not imply an ordinary sensing being. He italicizes the important terms, to say

I construed perception (as used by Bacon) as meaning taking account of the essential character of the thing perceived, and I construed sense as meaning cognition. We certainly do take account of things of which at the time we have no explicit cognition. We can even have a cognitive memory of the taking account, without having had a contemporaneous cognition. Also, as Bacon points out by his statement,'. . . for else all bodies would be alike one to another,' it is evidently some element of the essential character which we take account of, namely something on which diversity is founded and not mere bare logical diversity. The word perceive is, in our common usage, shot through and through with the notion of cognitive apprehension. So is the word apprehension, even with the adjective cognitive omitted. I will use the word prehension for uncognitive apprehension: by this I mean apprehension which may or may not be cognitive. Now take Euphranor's last remark:'Is it not plain, therefore, that neither the castle, the planet, nor the cloud, which you see here, are those real ones which you suppose exist at a distance?' Accordingly, there is a prehension, here in this place, of things which have a reference to other places.

Now go back to Berkeley's sentences, quoted from his Principles of Human Knowledge. He contends that what constitutes the realisation of natural entities is the being perceived within the unity of mind.

We can substitute the concept, that the realisation is a gathering of things into the unity of a prehension; and that what is thereby realised is the prehension, and not the things. This unity of a prehension defines itself as a here and a now, and the things so gathered into the grasped unity have essential reference to other places and other times.

Here Whitehead introduces the core idea of his process philosophy, the process of prehensive unification, a development of the ideas of Bacon, Berkeley, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz.For Berkeley's mind, I substitute a process of prehensive unification. In order to make intelligible this concept of the progressive realisation of natural occurrences, considerable expansion is required, and confrontation with its actual implications in terms of concrete experience. This will be the task of the subsequent lectures. In the first place, note that the idea of simple location has gone. The things which are grasped into a realised unity, here and now, are not the castle, the cloud, and the planet simply in themselves; but they are the castle, the cloud, and the planet from the standpoint, in space and time, of the prehensive unification. In other words, it is the perspective of the castle over there from the standpoint of the unification here. It is, therefore, aspects of the castle, the cloud, and the planet which are grasped into unity here. You will remember that the idea of perspectives is quite familiar in philosophy. It was introduced by Leibniz, in the notion of his monads mirroring perspectives of the universe. I am using the same notion, only I am toning down his monads into the unified events in space and time. In some ways, there is greater analogy with Spinoza's modes; that is why I use the terms mode and modal. In the analogy with Spinoza, his one substance is for me the one underlying activity of realisation individualising itself in an interlocked plurality of modes. Thus, concrete fact is process. Its primary analysis is into underlying activity of prehension, and into realised prehensive events. Each event is an individual matter of fact issuing from an individualisation of the substrate activity. But individualisation does not mean substantial independence.An entity of which we become aware in sense perception is the terminus of our act of perception. I will call such an entity, a sense-object... The way in which such an entity is related to space during a definite lapse of time is complex. I will say that a sense-object has ingression into space-time.

Thus primarily space-time is the locus of the modal ingression of sense-objects. This is the reason why space and time (if for simplicity we disjoin them) are given in their entireties. For each volume of space, or each lapse of time, includes in its essence aspects of all volumes of space, or of all lapses of time. The difficulties of philosophy in respect to space and time are founded on the error of considering them as primarily the loci of simple locations. Perception is simply the cognition of prehensive unification; or more shortly, perception is cognition of prehension. The actual world is a manifold of prehensions; and a 'prehension' is a 'prehensive occasion'; and a prehensive occasion is the most concrete finite entity, conceived as what it is in itself and for itself, and not as from its aspect in the essence of another such occasion...

There are more entities involved in nature than the mere sense-objects, so far considered. But, allowing for the necessity of revision consequent on a more complete point of view, we can frame our answer to Berkeley's question as to the character of the reality to be assigned to nature. He states it to be the reality of ideas in mind. A complete metaphysic which has attained to some notion of mind, and to some notion of ideas, may perhaps ultimately adopt that view. It is unnecessary for the purpose of these lectures to ask such a fundamental question. We can be content with a provisional realism in which nature is conceived as a complex of prehensive unifications. Space and time exhibit the general scheme of interlocked relations of these prehensions. You cannot tear any one of them out of its context. Yet each one of them within its context has all the reality that attaches to the whole complex. Conversely, the totality has the same reality as each prehension; for each prehension unifies the modalities to be ascribed, from its standpoint, to every part of the whole. A prehension is a process of unifying. Accordingly, nature is a process of expansive development, necessarily transitional from prehension to prehension. What is achieved is thereby passed beyond, but it is also retained as having aspects of itself present to prehensions which lie beyond it.

Thus nature is a structure of evolving processes. The reality is the process. It is nonsense to ask if the colour red is real. The colour red is ingredient in the process of realisation. The realities of nature are the prehensions in nature, that is to say, the events in nature...

An event has contemporaries. This means that an event mirrors within itself the modes of its contemporaries as a display of immediate achievement. An event has a past. This means that an event mirrors within itself the modes of its predecessors, as memories which are fused into its own content. An event has a future. This means that an event mirrors within itself such aspects as the future throws back onto the present, or, in other words, as the present has determined concerning the future. Thus an event has anticipation...

These conclusions are essential for any form of realism. For there is in the world for our cognizance, memory of the past, immediacy of realisation, and indication of things to come.

Whitehead here follows the nineteenth-century romantics and anticipates the late twentieth-century turn away from analytic philosophy to literature and the humanities for values.I propose in the first place to consider how the concrete educated thought of men has viewed this opposition of mechanism and organism. It is in literature that the concrete outlook of humanity receives its expression. Accordingly it is to literature that we must look, particularly in its more concrete forms, namely in poetry and in drama, if we hope to discover the inward thoughts of a generation...A scientific realism, based on mechanism, is conjoined with an unwavering belief in the world of men and of the higher animals as being composed of self-determining organisms. This radical inconsistency at the basis of modern thought accounts for much that is half-hearted and wavering in our civilisation...

Of course, we find in the eighteenth century Paley's famous argument, that mechanism presupposes a God who is the author of nature. But even before Paley put the argument into its final form, Hume had written the retort, that the God whom you will find will be the sort of God who makes that mechanism. In other words, that mechanism can, at most, presuppose a mechanic, and not merely a mechanic but its mechanic. The only way of mitigating mechanism is by the discovery that it is not mechanism.

When we leave apologetic theology, and come to ordinary literature, we find, as we might expect, that the scientific outlook is in general simply ignored.

Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Whitehead see what Alasdair MacIntyre would call the "dark at the core of the enlightenment" and that Ludwig Wittgenstein would rephrase in the last line of his Tractatus as what cannot be said, only can be shown. "The rest is silence."Wordsworth in his whole being expresses a conscious reaction against the mentality of the eighteenth century. This mentality means nothing else than the acceptance of the scientific ideas at their full face value. Wordsworth was not bothered by any intellectual antagonism. What moved him was a moral repulsion. He felt that something had been left out, and that what had been left out comprised everything that was most important. Tennyson is the mouthpiece of the attempts of the waning romantic movement in the second quarter of the nineteenth century to come to terms with science. By this time the two elements in modern thought had disclosed their fundamental divergence by their jarring interpretations of the course of nature and the life of man. Tennyson stands in this poem as the perfect example of the distraction which I have already mentioned. There are opposing visions of the world, and both of them command his assent by appeals to ultimate intuitions from which there seems no escape. Tennyson goes to the heart of the difficulty. It is the problem of mechanism which appalls him." "The stars,' she whispers, 'blindly run.' "If an organism is reducible to its molecules, which blindly run following Newtonian laws alone, the mind and responsibility are illusionsThis line states starkly the whole philosophic problem implicit in the poem. Each molecule blindly runs. The human body is a collection of molecules. Therefore, the human body blindly runs, and therefore there can be no individual responsibility for the actions of the body. If you once accept that the molecule is definitely determined to be what it is, independently of any determination by reason of the total organism of the body, and if you further admit that the blind run is settled by the general mechanical laws, there can be no escape from this conclusion. But mental experiences are derivative from the actions of the body, including of course its internal behaviour. Accordingly, the sole function of the mind is to have at least some of its experiences settled for it, and to add such others as may be open to it independently of the body's motions, internal and external.There are then two possible theories as to the mind. You can either deny that it can supply for itself any experiences other than those provided for it by the body, or you can admit them.

Whitehead is right that scientific materialism can not explain valuation and moral responsibilityIf you refuse to admit the additional experiences, then all individual moral responsibility is swept away. If you do admit them, then a human being may be responsible for the state of his mind though he has no responsibility for the actions of his body. The enfeeblement of thought in the modern world is illustrated by the way in which this plain issue is avoided in Tennyson's poem. There is something kept in the background, a skeleton in the cupboard. He touches on almost every religious and scientific problem, but carefully avoids more than a passing allusion to this one...Whitehead is wrong that "endurance" is unique to organisms. He is right that organisms have a "plan" or purpose, including, even in the smallest organisms, a kind of mentality, an immaterial manager of their creativity and bodily maintenance processesThe doctrine which I am maintaining is that the whole concept of materialism only applies to very abstract entities, the products of logical discernment. The concrete enduring entities are organisms, so that the plan of the whole influences the very characters of the various subordinate organisms which enter into it. In the case of an animal, the mental states enter into the plan of the total organism and thus modify the plans of the successive subordinate organisms until the ultimate smallest organisms, such as electrons, are reached. Thus an electron within a living body is different from an electron outside it, by reason of the plan of the body. The electron blindly runs either within or without the body; but it runs within the body in accordance with its character within the body; that is to say, in accordance with the general plan of the body, and this plan includes the mental state. But the principle of modification is perfectly general throughout nature, and represents no property peculiar to living bodies. In subsequent lectures it will be explained that this doctrine involves the abandonment of the traditional scientific materialism, and the substitution of an alternative doctrine of organism.I shall not discuss Mill's determinism, as it lies outside the scheme of these lectures. The foregoing discussion has been directed to secure that either determinism or free will shall have some relevance, unhampered by the difficulties introduced by materialistic mechanism, or by the compromise of vitalism. I would term the doctrine of these lectures, the theory of organic mechanism.

Molecules do not differ in their intrinsic character, but when part of an organism, they are governed by processes that implement the organism's own purposesIn this theory, the molecules may blindly run in accordance with the general laws, but the molecules differ in their intrinsic characters according to the general organic plans of the situations in which they find themselves.

We have bolded terms that will acquire very specific technical meanings for Whitehead in his next two works, especially in his magnum opus Process and Reality.

A year later, in 1926 Whitehead gave a second set of Lowell Lectures, this time at King's Chapel in Boston. They were published as Religion in the Making. Whitehead's embrace of religion and his idea of God account for his continued success among a subset of philosophers and theologians. His work is a throwback to before the presocratics who stopped explaining physical processes as the work of gods.

Recent editions of Religion in the Making have a technical glossary of terms, which is very helpful. The first two lectures include a brief history of religion, the major faiths and their dogmas. In lecture 3, "Body and Spirit," Whitehead builds on a few terms from Science and the Modern World, such as abstract, actual, event, experience, character, prehension, unification. He adds new terms, familiar words with new technical meanings, and several new terms - concretion, creature, creativity, entity, epochal, indetermination, realisation, occasion His magnum opus, Process and Reality, will again expand the Whitehead jargon, but much is here. See our draft of a Whitehead glossary below.

In the second half of the book, Whitehead begins to speak with terminology that is at once familiar yet jarring in his apparent meaning. The Dean of the Divinity School of the University of Chicago remarked on his first reading, "It is infuriating, and I must say embarrassing as well, to read page after page of relatively familiar words without understanding a single sentence."

There are many ways of analyzing the universe, conceived as that which is comprehensive of all that there is. In a description it is thus necessary to correlate these different routes of analysis. First, consider the analysis into (1) the actual world, passing in time; and (2) those elements which go to its formation. Such formative elements are not themselves actual and passing; they are the factors which are either non-actual or non-temporal, disclosed in the analysis of what is both actual and temporal.They constitute the formative character of the actual temporal world. We know nothing beyond this temporal world and the formative elements which jointly constitute its character. The temporal world and its formative elements constitute for us the all-inclusive universe. These formative elements are:

1. The creativity whereby the actual world has its character of temporal passage to novelty.2. The realm of ideal entities, or forms, which are in themselves not actual, but are such that they are exemplified in everything that is actual, according to some proportion of relevance.

3. The actual but non-temporal entity whereby the indetermination of mere creativity is transmuted into a determinate freedom...

A further elucidation of the status of these formative elements is only to be obtained by having recourse to another mode of analysis of the actual world.The actual temporal world can be analyzed into a multiplicity of occasions of actualization. These are the primary actual units of which the temporal world is composed. Call each such occasion an "epochal occasion." Then the actual world is a community of epochal occasions. In the physical world each epochal occasion is a definite limited physical event, limited both as to space and time, but with time-duration as well as with its full spatial dimensions.

Whitehead's version of relativity is that things are not simply located in some absolute space and time, but are only located relative to all other things in the universe.The epochal occasions are the primary units of the actual community, and the community is composed of the units. But each unit has in its nature a reference to every other member of the community, so that each unit is a microcosm representing in itself the entire all-inclusive universe.Whitehead should connect his organic creatures to the fourth great idea from the nineteeeth century, evolution. Material particles do not evolve as they blindly run. Organic creatures do evolve as they combine diverse elements to create new emergent properties.These epochal occasions are the creatures. The reason for the temporal character of the actual world can now be given by reference to the creativity and the creatures.... Thus there is a transition of the creative action, and this transition exhibits itself, in the physical world, in the guise of routes of temporal succession...An epochal occasion is a concretion. It is a mode in which diverse elements come together into a real unity. Apart from that concretion, these elements stand in mutual isolation. Thus an actual entity is the outcome of a creative synthesis, individual and passing...

Whitehead's concretion, later called concrescence, is emergentThus the epochal occasion, which is thus emergent, has in its own nature the other creatures under the aspect of these forms, and analogously it includes the forms under the aspect of these creatures. It is thus a definite limited creature, emergent in consequence of the limitations thus mutually imposed on each other by the elements.

Descartes has the great merit that he states facts which any philosophy must fit into its scheme. There are bits of matter, and there are minds. Both matter and mind have to be fitted into the metaphysical scheme.Here is Whitehead as a Berkeleyan idealist. To be is to be perceivedBut Whitehead is wrong that the entities gain their individual character from their "routes" (in space time). It is from their creative interactions with all the other entities in their communities.Now, according to the doctrine of this lecture, the most individual actual entity is a definite act of perceptivity. So matter and mind, which persist through a route of such occasions, must be relatively abstract; and they must gain their specific individualities from their respective routes. The character of a bit of matter must be something common to each occasion of its route; and analogously, the character of a mind must be something common to each occasion of its route. Each bit of matter, and each mind, is a subordinate community—in that sense analogous to the actual world...VII. THE CREATIVE PROCESS

This account of what is meant by the enduring existence of matter and of mind explains such endurance as exemplifying the order immanent in the world...

Accordingly, any given instance of experience is only possible so far as the antecedent facts permit. For they are required in order to constitute it. The maintenance, throughout ages of life history, of a given type of experience, in instance after instance of its separate occasions, requires, therefore, the stable order of the actual world.

The creative process is thus to be discerned in that transition by which one occasion, already actual, enters into the birth of another instance of experienced value. There is not one simple line of transition from occasion to occasion, though there may be a dominant line...

The birth of a new instance is the passage into novelty. Consider how any one actual fact, which I will call the ground, can enter into the creative process.

Whitehead sees clearly that his creative process brings new information into the universe in the form of ideas, whether purely mental or embodied in material.The novelty which enters into the derivate instance is the information of the actual world with a new set of ideal forms. In the most literal sense the lapse of time is the renovation of the world with ideas. A great philosopher (Samuel Alexander) has said that time is the mind of space. In respect to one particular new birth of one centre of experience, this novelty of ideal forms will be called the "consequent."Later Whitehead will say that multiple grounds, the antecedent facts of many prior occasions, will come together in one consequent.Thus we are now considering the particular relevance of the consequent to the particular ground supplied by one antecedent occasion. The derivate includes the fusion of the particular ground with the consequent, so far as the consequent is graded by its relevance to that ground.Later Whitehead will say that the actual and not actual that enter the process are possibilitiesIn this fusion of ground with consequent, the creative process brings together something which is actual and something which, at its entry into that process, is not actual. The process is the achievement of actuality by the ideal consequent, in virtue of its union with the actual ground. In the phrase of Aristotle, the process is the fusion of being with not-being.

In Whitehead's great work of 400 pages, Process and Reality, we can only sample his thinking, but there is a partial continuity in his jargon with his two previous books. A major novelty is his introduction of a Kantian/Hegelian architectonic of new categories, a single Category of the Ultimate, eight Categories of Existence, twenty-seven Categories of Explanation, and nine Categorial Obligations. He introduces his Categoreal Scheme by defining the four basic notions of the philosophy of organism - an 'actual entity,' that of a 'prehension,' that of a 'nexus,' and that of the 'ontological principle.' Whitehead finds clear antecedents of his thought in Descartes, Leibniz, Locke, Kant, and Plato.

This chapter contains an anticipatory sketch of the primary notions which constitute the philosophy of organism. The whole of the subsequent discussion in these lectures has the purpose of rendering this summary intelligible, and of showing that it embodies generic notions inevitably presupposed in our reflective experience—presupposed, but rarely expressed in explicit distinction. Four notions may be singled out from this summary, by reason of the fact that they involve some divergence from antecedent philosophical thought. These notions are, that of an 'actual entity,' that of a 'prehension,' that of a 'nexus,' and that of the 'ontological principle.' Philosophical thought has made for itself difficulties by dealing exclusively in very abstract notions, such as those of mere awareness, mere private sensation, mere emotion, mere purpose, mere appearance, mere causation. These are the ghosts of the old 'faculties,' banished from psychology, but still haunting metaphysics. There can be no 'mere' togetherness of such abstractions. The result is that philosophical discussion is enmeshed in the fallacy of 'misplaced concreteness.'1 In the three notions— actual entity, prehension, nexus—an endeavour has been made to base philosophical thought upon the most concrete elements in our experience.1 Cf. my Science and the Modern World, Ch. III.'Actual entities'—also termed 'actual occasions'—are the final real things of which the world is made up. There is no going behind actual entities to find anything more real. They differ among themselves: God is an actual entity, and so is the most trivial puff of existence in far-off empty space. But, though there are gradations of importance, and diversities of function, yet in the principles which actuality exemplifies all are on the same level. The final facts are, all alike, actual entities; and these actual entities are drops of experience, complex and interdependent.

The 'ontological principle' is that actual entities are ontological substancesIn its recurrence to the notion of a plurality of actual entities the philosophy of organism is through and through Cartesian! The 'ontological principle' broadens and extends a general principle laid down by John Locke in his Essay (Bk. II, Ch. XXIII, Sect. 7), when he asserts that "power" is "a great part of our complex ideas of "substances." The notion of 'substance' is transformed into that of 'actual entity'; and the notion of 'power' is transformed into the principle that the reasons for things are always to be found in the composite nature of definite actual entities— in the nature of God for reasons of the highest absoluteness, and in the nature of definite temporal actual entities for reasons which refer to a particular environment. The ontological principle can be summarized as: no actual entity, then no reason.Each actual entity is analysable in an indefinite number of ways. In some modes of analysis the component elements are more abstract than in other modes of analysis. The analysis of an actual entity into 'prehensions' is that mode of analysis which exhibits the most concrete elements in the nature of actual entities. This mode of analysis will be termed the 'division' of the actual entity in question.

Prehensions have a vector character because they are causes, purposes, and values coming it to the actual entity from the past.Each actual entity is 'divisible' in an indefinite number of ways, and each way of 'division' yields its definite quota of prehensions. A prehension reproduces in itself the general characteristics of an actual entity: it is referent to an external world, and in this sense will be said to have a 'vector character'; it involves emotion, and purpose, and valuation, and causation. In fact, any characteristic of an actual entity is reproduced in a prehension. It might have been a complete actuality; but, by reason of a certain incomplete partiality, a prehension is only a subordinate element in an actual entity. A reference to the complete actuality is required to give the reason why such a prehension is what it is in respect to its subjective form. This subjective form is determined by the subjective aim at further integration, so as to obtain the 'satisfaction' of the completed subject. In other words, final causation and atomism are interconnected philosophical principles.With the purpose of obtaining a one-substance cosmology, 'prehensions' are a generalization from Descartes' mental 'cogitations,' and from Locke's 'ideas,' to express the most concrete mode of analysis applicable to every grade of individual actuality. Descartes and Locke maintained a two-substance ontology—Descartes explicitly, Locke by implication. Descartes, the mathematical physicist, emphasized his account of corporeal substance; and Locke, the physician and the sociologist, confined himself to an account of mental substance.

The philosophy of organism combines Locke's ideas and Cartesian cogitations (res cogitans), as well as Descartes' res extensa and Leibniz's monadsThe philosophy of organism, in its scheme for one type of actual entities, adopts the view that Locke's account of mental substance embodies, in a very special form, a more penetrating philosophic description than does Descartes' account of corporeal substance. Nevertheless, Descartes' account must find its place in the philosophic scheme. On the whole, this is the moral to be drawn from the Monadology of Leibniz. His monads are best conceived as generalizations of contemporary notions of mentality. The contemporary notions of physical bodies only enter into his philosophy subordinately and derivatively. The philosophy of organism endeavours to hold the balance more evenly. But it does start with a generalization of Locke's account of mental operations.Actual entities involve each other by reason of their prehensions of each other. There are thus real individual facts of the togetherness of actual entities, which are real, individual, and particular, in the same sense in which actual entities and the prehensions are real, individual, and particular. Any such particular fact of togetherness among actual entities is called a 'nexus' (plural form is written 'nexūs'). The ultimate facts of immediate actual experience are actual entities, prehensions, and 'nexūs. All else is, for our experience, derivative abstraction.

The explanatory purpose of philosophy is often misunderstood. Its business is to explain the emergence of the more abstract things from the more concrete things. It is a complete mistake to ask how concrete particular fact can be built up out of universals. The answer is, 'In no way.' The true philosophic question 2 is, How can concrete fact exhibit entities abstract from itself and yet participated in by its own nature?

Whitehead's Plato here seems to have absorbed the Aristotelean view that Plato's Forms are abstractions from, and 'participants in, the concrete facts?In other words, philosophy is explanatory of abstraction, and not of concreteness. It is by reason of their instinctive grasp of this ultimate truth that, in spite of much association with arbitrary fancifulness and atavistic mysticism, types of Platonic philosophy retain their abiding appeal; they seek the forms in the facts. Each fact is more than its forms, and each form 'participates' throughout the world of facts. The definiteness of fact is due to its forms; but the individual fact is a creature, and creativity is the ultimate behind all forms, inexplicable by forms, and conditioned by its creatures.2 In this connection I may refer to the second chapter of my book The Principle of Relativity, Cambridge University Press,t 192

We can also compare this to Whitehead's relativistic space-time diagram from his April 14, 1925 Lowell Lecture.

The word 'decision' does not here imply conscious judgment, though in some 'decisions' consciousness will be a factor. The word is used in its root sense of a 'cutting off.' The ontological principle declares that every decision is referable to one or more actual entities, because in separation from actual entities there is nothing, merely nonentity—'The rest is silence.'The ontological principle asserts the relativity of decision; whereby every decision expresses the relation of the actual thing, for which a decision is made, to an actual thing by which that decision is made. But 'decision' cannot be construed as a casual adjunct of an actual entity. It constitutes the very meaning of actuality. An actual entity arises from decisions for it, and by its very existence provides decisions for other actual entities which supersede it. Thus the ontological principle is the first stage in constituting a theory embracing the notions of 'actual entity,' 'givenness,' and 'process.' Just as 'potentiality for process' is the meaning of the more general term 'entity,' or 'thing'; so 'decision' is the additional meaning imported by the word 'actual' into the phrase 'actual entity.' 'Actuality' is the decision amid 'potentiality.' It represents stubborn fact which cannot be evaded. The real internal constitution of an actual entity progressively constitutes a decision conditioning the creativity which transcends that actuality.

Whitehead's ninth Categoreal Obligation is the very important Category of Freedom and Determination, which he finds discussed in Locke and Immanuel Kant. Whitehead says

the concrescence of each individual actual entity is internally determined and externally free. This category can be condensed into the formula, that in each concrescence whatever is determinable is determined, but that there is always a remainder for the decision of the subject-superject of that concrescence.This subject-superject is the universe in that synthesis, and beyond it there is nonentity. This final decision is the reaction of the unity of the whole to its own intemal determination. This reaction is the final modification of emotion, appreciation, and purpose. But the decision of the whole arises out of the determination of the parts, so as to be strictly relevant to it.

Isabelle Stengers analyzed Whitehead's idea of a "decision" in an actual occasion.

At the end of Part One of her Thinking with Whitehead, Stengers notes that an "actual occasion" contains multiple incoming prehensions from past occasions which Whitehead calls "alternative suggestions." These she identifies with William James's alternative possibilities, which is the basis of two-stage models of free will.

Stengers quotes this fragment from Science and the Modern World.

every actual occasion is set within a realm of alternative interconnected entities. This realm is disclosed by all the untrue propositions which can be predicated significantly of that occasion. It is the realm of alternative suggestions, whose foothold in actuality transcends each actual occasion. The real relevance of untrue propositions for each actual occasion is disclosed by art, romance, and by criticism in reference to ideals. It is the foundation of the metaphysical position which I am maintaining that the understanding of actuality requires a reference to ideality. The two realms are intrinsically inherent in the total metaphysical situation. The truth that some proposition respecting an actual occasion is untrue may express the vital truth as to the aesthetic achievement. It expresses the ‘great refusal’ which is its primary characteristic. An event is decisive in proportion to the importance (for it) of its untrue propositions:

Stengers' analysis contains echoes of the great existentialists' notions that any "decision" involves the "destruction" of some alternative possibilities condemning them to "non-being." For example, Jean-Paul Sartre's L'être et le néant.

Then Stengers homes in on James' notion of "doing otherwise as the essence of a free decision."

Sometimes, in the course of this text, I have been unable not to anticipate, and to use the word "decision," which Whitehead was to use in Process and Reality to name the "breaking off" that turns the occasion into the affirmation of a "thus and not otherwise." When he named the "great refusal," Whitehead himself could doubtless not help but be inhabited by a syntax that makes the occasion the producer of its limitation. No doubt he was aware, when writing Science and the Modern World, that his concept of an occasion was merely a first approximation. And perhaps the use of the word "decision," in Process and Reality, indicates that he has henceforth provided himself with the means to fully affirm the meaning William James conferred upon this term: that of a living moment that produces its own reasons.Decisions, for him who makes them, are altogether peculiar psychic facts. Self-luminous and self-justifying at the living moment at which they occur, they appeal to no outside moment to put its stamp upon them or make them continuous with the rest of nature. Themselves it is rather who seem to make nature continuous; and in their strange and intense function of granting consent to one possibility and withholding it from another, to transform an equivocal and double future into an inalterable and simple past (DD, 158).

With James, Whitehead refused to make continuity primary; that is, he also refused to allow the occasion to be deduced from the whole. Every continuity is a result, a succession of resumptions that are so many "purposes," deciding the way the present will prolong the past, give a future to this past and make it "its" past. Yet the way James characterizes decision, "granting consent to one possibility and withholding it from another," could not be adopted as such, for it contains too many unknowns. It had to be constructed, in a way that enables every production of existence to be characterized as a decision. It is the actual occasions themselves that will affirm, no longer merely "just this, and no more," but "thus and not otherwise."

Continuity is the essential nature of field theories, with their infinite number of points on a line. Whitehead's atomicity of experience suggests he favors a particulate view of nature, with a finite number of actual entities?

In his Chapter X on Process, Whitehead again tells us that some of his most important concepts about process come from John Locke. The clear talk about Locke devolves into obscure Whitehead jargon.

[T]here are two kinds of fluency. One kind is the concrescence which, in Locke's language, is 'the real internal constitution of a particular existent.' The other kind is the transition from particular existent to particular existent. This transition, again in Locke's language, is the 'perpetually perishing' which is one aspect of the notion of time; and in another aspect the transition is the origination of the present in conformity with the 'power' of the past.The phrase 'the real internal constitution of a particular existent,' the description of the human understanding as a process of reflection upon data, the phrase 'perpetually perishing,' and the word 'power' together with its elucidation are all to be found in Locke's Essay. Yet owing to the limited scope of his investigation Locke did not generalize or put his scattered ideas together. This implicit notion of the two kinds of flux finds further unconscious illustration in Hume. It is all but explicit in Kant, though—as I think—misdescribed. Finally, it is lost in the evolutionary monism of Hegel and of his derivative schools. With all his inconsistencies, Locke is the philosopher to whom it is most useful to recur, when we desire to make explicit the discovery of the two kinds of fluency, required for the description of the fluent world. One kind is the fluency inherent in the constitution of the particular existent. This kind I have called 'concrescence.' The other kind is the fluency whereby the perishing of the process, on the completion of the particular existent, constitutes that existent as an original element in the constitutions of other particular existents elicited by repetitions of process. This kind I have called 'transition.' Concrescence moves towards its final cause, which is its subjective aim; transition is the vehicle of the efficient cause, which is the immortal past. The discussion of how the actual particular occasions become original elements for a new creation is termed the theory of objectification. The objectified particular occasions together have the unity of a datum for the creative concrescence. But in acquiring this measure of connection, their inherent presuppositions of each other eliminate certain elements in their constitutions, and elicit into relevance other elements. Thus objectification is an operation of mutually adjusted abstraction, or elimination, whereby the many occasions of the actual world become one complex datum. This fact of the elimination by reason of synthesis is sometimes termed the perspective of the actual world from the standpoint of that concrescence. Each actual occasion defines its own actual world from which it originates. No two occasions can have identical actual worlds.

History discloses two main tendencies in the course of events. One tendency is exemplified in the slow decay of physical nature. With stealthy inevitableness, there is degradation of energy. The sources of activity sink downward and downward. Their very matter wastes. The other tendency is exemplified by the yearly renewal of nature in the spring, and by the upward course of biological evolution.

The material universe has contained in itself, and perhaps still contains, some mysterious impulse for its energy to run upwards. This impulse is veiled from our observation, so far as concerns its general operation. But there must have been some epoch in which the dominant trend was the formation of protons, electrons, molecules, and stars. Today, so far as our observations go, they are decaying. We know more of the animal body, through the medium of our personal experience. In the animal body, we can observe the appetition towards the upward trend, with Reason as the selective agency. In the general physical universe we cannot obtain any direct knowledge of the corresponding agency by which it attained its present stage of available energy...The universe, as construed solely in terms of the efficient causation of purely physical interconnections, presents a sheer, insoluble contradiction... The moral to be drawn from the general survey of the physical universe with its operations viewed in terms of purely physical laws, and neglected so far as they are inexpressible in such terms, is that we have omitted some general counter-agency.

Information philosophy has discovered Whitehead's "counter-agency as the cosmic creation processThis counter-agency in its operation throughout the physical universe is too vast and diffusive for our direct observation. We may acquire such power as the result of some advance. But at present, as we survey the physical cosmos, there is no direct intuition of the counter-agency to which it owes its possibility of existence as a wasting finite organism.

Whitehead hopes to discover some underlying "purpose," which he sees clearly present in biological evolution as "foresight" and "intention." He describes the function of "Reason" as the promotion of "the art of life." (p.4) And he says "At the lower end of the scale, it is hazardous to draw any sharp distinction between living things and inorganic matter." (p.5) This will open the way to his panpsychist view of a "mysterious impulse" behind energy.

Reason is the organ of emphasis upon novelty. It provides the judgment by which realization in idea obtains the emphasis by which it passes into realization in purpose, and thence its realization in fact. (ibid., p.20)Provided that we admit the category of final causation, we can consistently define the primary function of Reason. This function is to constitute, emphasize, and criticize the final causes and strength of aims directed towards them. The pragmatic doctrine must accept this definition. It is obvious that pragmatism is nonsense apart from final causation. (ibid., p.26) )

Following Kant, Whitehead distinguishes between practical and speculative Reason, the latter being the systematic philosophy of the early Greeks.

the critical discovery which gave to the speculative Reason its supreme importance was made by the Greeks. Their discovery of mathematics and of logic introduced method into speculation. Reason was now armed with an objective test and with a method of progress. In this way Reason was freed from its sole dependence on mystic vision and fanciful suggestion. (ibid., p.40)

We can note in passing that Whitehead is not what Kant called an "onto-theologist," one who hopes to discover God by thinking about the concept of "Being," the "Boundless", the "Indeterminate," etc. Whitehead was what Kant called a "cosmo-theologist," one who tries to discern God through our experiences with the natural world.

Today we describe this as "reductionism," the mistaken idea that all phenomena are reducible to physics and chemistry, that biological organisms and even mental phenomena are reducible to the motions of their constituent material particles.

Reductionism claims that there are deterministic causal chains coming "bottom up" from matter. If there are "mental phenomena," they are merely "epiphenomena," giving us the illusion of mental events and "mental causation."

Whitehead thought relativity and quantum mechanics had added something new to mechanical materialism. He was wrong about relativity, but right about quantum physics, though he did not understand what it is that quantum phenomena add to biological organisms and mental processes. And he did not see the importance of another physical process that his British colleague Arthur Stanley Eddington called attention to, the second law of thermodynamics, in his Gifford Lectures the same year as those of Whitehead.

Perhaps the greatest similarity between I-Phi and Process Philosophy is that they both claim to explain a "creative process," which lies behind the "emergence of "purpose" (the entelechy of Aristotle or the teleonomy of Colin Pittendrigh and Jacques Monod) in living things.

- System: Both information and process philosophy are systematic philosophies, applying a small set of principles to everything from elementary particles to cosmology, and explaining evolution all the way from inert matter to living things.

- Organism: Whitehead says he wanted to avoid a "bifurcation" between the organic and inorganic world.. But when he applies his ideas that describe mental events like perception, experience, valuations, etc. all the way down to material particles, he mistakenly introduces panpsychism. Whitehead simply describes the physical processes of matter in space and time using terms that are only appropriate for biological entities, like perception, decision, valuation, etc. He transforms an entirely material space-time "event" into an "occasion" with mental properties. But saying such a thing does not make it so, even if Whitehead says that God is overseeing the process..

By contrast, the information philosophy emphasis on the creation of information structures distinguishes the creation of passive structures like the galaxies, stars, planets, even elementary material particles, from active information structures that communicate information among their parts and to and from other active structures to form a community of living things (something like Whitehead's "nexūs" or "societies").

For information philosophy, an organism is a form through which matter and energy flow, and information processes manage those flows. For passive structures, the flows are controlled entirely by natural forces like gravity, electromagnetism, and nuclear forces.

Like process philosophy, there is no "vitalism" in information philosophy. Nor is there any "telos" or pre-existing purpose. Thus cosmic evolution is purposeless, yet it contains the creation of information structures with negative entropy that can be intrpreted as a benevolent and even divine providence that supports all living things in the universe.

- Experience: Process philosophy and information philosophy both stress the importance of experience. Where Whitehead describes experience as the "becoming" of an actual occasion, information philosophy shows how experiences are recorded and reproduced in organisms with minds, however primitive. Past experiences, played back in similar situations by our Experience Recorder and Reproducer (ERR), are guides for actions, both practical and moral.

Recording experiences in minds - Whitehead's actual occasions - then storing their content as knowledge external to minds, is the basis for humanity's extraordinary growth of natural knowledge. Whitehead's processes tell us nothing about the creation of such value.

- Valuation: Although Whitehead's category of conceptual valuation suggested that feelings in an actual occasion would register a valuation "up" or "down," like all attempts to identify an objective criterion of value since the Enlightenment, Whitehead offers no measure of value. Information philosophy identifies the preservation of information as a universal good, beyond traditional, religious, humanistic, or bioethical standards. Information structures are a cosmic good. The entropic dissipative processes of the second law of thermodynamics are evil incarnate.

- Quantum Effects: Whitehead was familiar with quantum mechanics and argued that a quantum of time would help the "duration" for his actual occasion.

Information philosophy claims that the indeterminacy in quantum events is important for the creation of new alternative possibilities.

- Chance: Although his major writing was before Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, Whitehead seems to accept chance as needed for evolution. He wrote "The doctrine of evolution has to do with the emergence of novel organisms as the outcome of chance." The ontological chance of quantum physics is essential for the creation of new information in the universe. This is the "novelty" in creativity that Whitehead described.

Also see our I-Phi glossary of terms related to problems of freedom, value, and knowledge uses hyperlinks (with blue underlines) to provide recursive definitions from within each entry.

Hyperlinks go to relevant pages in the I-Phi website and to external sites such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, where available.

Click on the "Search I-Phi" link to find all the webpages on the I-Phi website that refer to the given term. And click on "I-Phi Page" to get a much more detailed description of the term.

"'Actual entities' - also termed 'actual occasions' - are the final real things of which the world is made up...God is an actual entity."(PR18) "The term 'actual occasion will always exclude God from its scope." (PR88)

"The real internal constitution of an actual entity progressively constitutes a decision conditioning the creativity which transcends that actuality." (PR230)

"To be causa sui means that the process of concrescence is its own reason for the decision in respect to the qualitative clothing of feelings...The freedom inherent in the universe is constituted by this element of self-causation. (PR88)

"Locke is the philosopher to whom it is most useful to recur, when we desire to make explicit the discovery of the two kinds of fluency, required for the description of the fluent world. This kind I have called 'concrescence.' The other kind is the fluency the perishing of the process, on the completion of the particular existent, constitutes that existent as an original element in the constitutions of other particular existents elicited by repetitions of process. This kind I have called 'transition.' Concrescence moves towards its final cause, which is its subjective aim; transition is the vehicle of the efficient cause, which is the immortal past."

Creativity, the Many, and the One are the three parts of the "Category of the Ultimate."

An Ideal Entity is an ideal or Abstract Form.

An Eternal Object is an immaterial Form or Idea that exists outside of space and time. The Platonic Forms, logical truths, and the mathematical entities in his Principia Mathematica are Eternal Objects. They are pure potential that can be realized in an Actual Entity. All Objects can be Perceived and Felt by Subjects.

indetermination

Macroscopic processes are made up of multiple occasions in a Nexus or society of occasions

A Microscopic process of Concrescence is one that is not temporal. Here the "earlier" Prehensions are only logical, not actual, preconditions for the Occasion.

What many philosophers call “actual entities,” Whitehead calls “nexūs.” This is most obvious in relation to philosophies that stay close to ordinary language and treat the objects of everyday experience as actual entities. Many process philosophers take Events as primary, though for Whitehead, most Events are Nexūs, multiple actual occasions.

Whitehead sometimes describes multiple Nexūs as Societies.

An occasion may be something material happening in nature, or something mental happening in a mind.

Occasions function as Causes to its successor Occasions, which are affected by it as the Ingression of Prehensions.

Whitehead often describes occasions with other terms, such as Actual Entities, Creatures, Concretions,

For Whitehead, every entity is considered to be an organism. This is a fundamental error. Organisms are biological entities. They maintain themselves against breakdown by the second law of thermodynamics, using negative entropy streams from the sun that flow through all earthly life. Organisms are creative, evolving according to the neo-Darwinian synthesis.

Organisms are Forms through which Matter and Energy continuously flow. And it is information communications and processing that controls those flows, using negative entropy that flows from the sun to all life.

Whitehead describes the physical processes of matter in space and time using terms that are only appropriate for biological entities, like perception, decision, valuation, etc. He transforms an entirely material space-time "event" into an "occasion" with mental properties. But saying such a thing does not make it so, even if Whitehead says that God is overseeing the process.

By contrast, the information philosophy emphasis on the creation of information structures distinguishes the creation of passive structures like the galaxies, stars, planets, even elementary material particles, from active information structures that communicate information among their parts and to and from other active structures to form a community of living things (something like Whitehead's "nexūs" or "societies").

For information philosophy, an organism is a form through which matter and energy flow, and information processes manage those flows. For passive information structures like elementary particles, as well as the galaxies, stars, and planets, matter and energy flows are controlled entirely by natural forces like gravity, electromagnetism, and nuclear forces.

Physical prehensions are perceptions of actual entities or actual occasions. Conceptual prehensions are "ingressions" of eternal objects.

Prehensions are the first stage (the Many Grounds) which grow together in the Concrescence that results in a Consequent One

"The actual entity terminates its becoming in one complex feeling involving a completely determinate bond with every item of the universe, the bond being either a positive or a negative prehension." (PR71) The 'satisfaction' is the 'superject' of rather than the 'substance' or the 'subject.' (PR227)

"An actual entity is to be conceived both as a subject presiding over its own immediacy of becoming, and a superject which is the atomic creature exercising its function of objective immortality." (PR71)

By comparison, there is no temporal Transition in Microscopic process of Concrescence. Here the "earlier" Prehensions are only logical preconditions for the Occasion, viz. Eternal Objects