The Postmodern John Cobb

deconstructive and constructive

What's to deconstruct about Modernity?

Eight things, says John Cobb, in the essay below:

- Christianism

- Modern Metaphysics

- Modern Science

- Modern Nationalism

- Economism

- Modern Defense

- American Exceptionalism

- The University

Does anything have "value"?

The world of people, animals, and the earth is filled with value. Its value does not lie simply in the usefulness of things but in their interiority, their subjectivity, their reality in and for themselves as they interact with one another. Human beings, too, have this value, and it is supremely important. The value of the world is appreciated and enfolded within the life of Abba, and it has powerful implications for how we treat one another and the more-than-human world. See Whitehead's Theory of Value and Economic Justice and Process Philosophy.

Is there a social and philosophical alternative to Modernity?

The alternative is the emergence in our world of "communities of communities of communities," each of which embodies the spirit and practice of Ecological Civilization, These communities are creative, compassionate, participatory, inclusive, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying, with no one left behind. Their focus is not on money or on imperial aspirations, or even on individual happiness at the expense of community health; but on the well-being and flourishing of people, animals, and the earth. See Five Foundations for an Ecological Civilization and Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet.

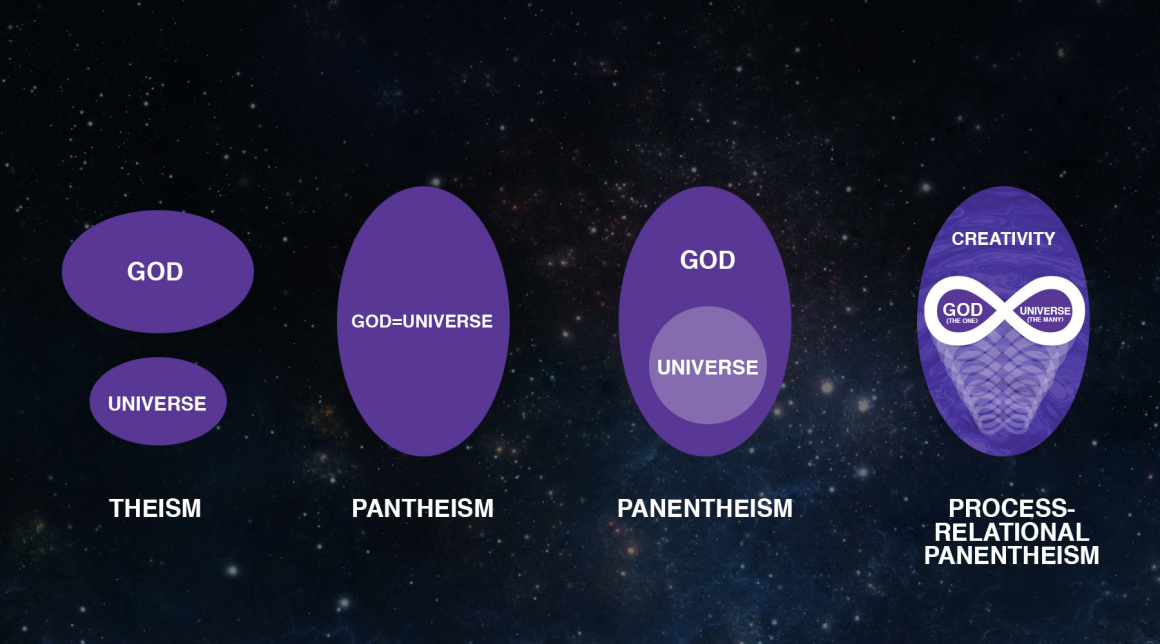

Can a postmodern world include belief in God?

Yes. But it is important to keep in mind that the word "God" has different meanings, and not all people in such a world will find it a helpful word. A constructively postmodern world includes people who believe in God, people who do not, and the many who are somewhere in between. For those who believe, John Cobb recommends that God be conceived as Abba, not as an all-powerful ruler or cosmic moralist. God is more concerned with the well-being and flourishing of life than in being worshipped or flattered. See God as Abba: John Cobb's Proposal.

* * * * * * * * * * *

by John B. Cobb, Jr.

Whitehead’s followers have long called themselves “postmodern.” When the French postmodernists defined postmodernism as “deconstruction” of the modern, Whiteheadians distinguished themselves as “constructive postmodernists.” We prefer to emphasize the positive. When we learned from China to call the world we work for “ecological civilization,” this further accented the positive.

This has led us to mute our criticism of the modern. Our call for an organic worldview obviously implies criticism of the mechanistic one. Our call for multinational cooperation obviously implies criticism of nationalism and imperialism. Our call for orienting education toward ecological civilization obviously implies criticism of “value-free” universities. But the needed deconstruction has been muted.

This emphasis on the positive has made it easier for people to join us. But many who now talk about moving toward an ecological civilization retain features of modernity that in fact prevent them from moving very far. Too often, affirming an ecological civilization means little more than being ecologically sensitive. In fact, ecological civilization calls for profound changes and significant sacrifices.

This article joins the deconstructive postmodernists. It focuses on what must be changed and overcome. It opposes any effort to reassure and bring comfort. One may legitimately object to the harshness of its negations. They are not the whole story, but they are the part of the story that we “constructive postmodernists” have not done enough to highlight. So here goes with eight obstacles to an ecological civilization.

Christianism

Not all Christianity is “Christianism.” There are people who seek to serve God and humanity by following Jesus and understand that affirmations of Christianity as the only way or lashing out at its opponents are damaging. But Christians have too often absolutized the church or the Bible or what they have understood by “God.” Christianism is a form of idolatry no better and no worse than the many other forms of idolatry that have informed so much of history. Charlemagne taught his soldiers that they would be rewarded for killing opponents of what he viewed as orthodox Christianity. This spirit fueled Crusades against Muslims and “heretics.

Modernity has largely liberated society from Christianism. But not entirely. It is still an obstacle to be recognized and opposed. We can move toward ecological civilization only if the great moral and spiritual traditions of the world work together. The last century has witnessed great progress, but Christianism remains as an obstacle. It is an obstacle to authentic response to Jesus, and just for that reason, to openness to humble sharing with others in working for the “divine commonwealth” about which Jesus testified.

The other great traditions have similar dangers and limitations. In this essay, I focus on the obstacles most important for Americans. Thus far, Christianism has been No. 1.

Modern Metaphysics

By modern metaphysics I mean the metaphysical tradition that was initiated by Rene Descartes. It has taken many forms. Most philosophers today repudiate Descartes, yet the influence remains. Indeed, the first, and perhaps the greatest obstacle to deconstructing the metaphysics that still rules the world is that most people, and especially most philosophers and scientists deny that they have a metaphysics. When one’s metaphysics thoroughly shapes the way one perceives the world, it becomes nonconscious.

Most modern people suppose that our best source of knowledge of the external world is through sight. “Seeing is believing.” Of course, they know that that world is not simply the patches of colors that are attained by sight. Those colors are the colors of something. The “something” is a substance, that, it is what the color inheres in. This is material in nature. It is material entities that science studies. Matter cannot be identified visually or by the data of any of the senses. It has no subjective reality. That is, it does not feel or have purposes. It is not an agent. When it moves, it is because something moves it. Thus nature, the world studied by science, is constituted by matter in motion.

Descartes taught that the only exception to this is the human soul. We know ourselves as feeling, purposing, acting beings. He thought the soul is not material at all. Charles Darwin confused moderns profoundly by showing that human beings are part of the nature that Descartes taught them to understand as matter in motion. Many moderns give lip service to this view, but in fact they do not think of themselves as simply machine-like. Today, many are recognizing that in addition to machine-like nature, including human bodies, there is also what Descartes called the human soul. Today we call it “consciousness.”

A few philosophers have simply denied the existence of matter and held that everything is soul-like, psychic. There are others who say that we should stick to the appearances and not take any position on what is appearing. There are still others who don’t want to get into these issues and talk only about language. I cannot survey the history of modern metaphysical thought in a page. I am trying to identify what became in modern times a kind of common sense. I believe that has been the dualism of matter and mind introduced by Descartes.

This dualism leaves open the question of where the line should be drawn. Even those who may verbally limit mind to the human soul are likely to actually feel that their pet dog is not adequately understood as matter in motion. It seems to have feelings and purposes. Descartes’ serious insistence that it has no feelings has never become part of modern common sense, but his teaching has nevertheless given license to vivisection of animals and to the industrial production of meat. Modern common sense has always been seriously confused.

The problem is not only confusion. It is also that this modern common sense justifies much that is unjustifiable and gives poor guidance in relation to much else. Instead of illustrating this now, I will take up the problems in subsequent sections.

Constructive postmodernism calls for the rejection of both pure matter and pure mind. It rejects the mechanistic model and calls for an organic one. Whitehead described his thought as a philosophy of organism. We constructive postmodernists prefer to attract people to thinking in these new ways, but it turns out that unless the hold of materialism and dualism is broken, vague feelings about organisms do not reshape thought.

Modern Science

Modern science is the science that followed the guidance of Descartes. In the science of the high and late Middle Ages, the most influential philosopher had been Aristotle. He taught that to understand something we should pursue four questions: first, what is it made of; second, what is its form; third, what made it come into being; and fourth, to what end did in come into being? These are called the four explanations or causes: material, formal, efficient, and final. Scientists have always been interested in the first three causes, but under the influence of Aristotle, in the late Middle Ages they tended to focus on the final cause. For example, in their study of the human body they wanted to understand the role or function of the liver, the kidneys, the heart, and so forth.

Descartes was convinced that this function was only superficially explanatory. The scientific question was not whether the heart pumped blood but how it did so. That is the question about the efficient cause. What made the heart pump? Descartes insisted that nothing is explained by the final cause. Purposes play no role in nature. Descriptively, we may of course note that the circulatory system could not function without the pumping of the blood, but the task of science is not this description but an explanation of how and why the heart pumps.

To insure that we do not attribute purposes to the heart, Descartes insisted that it functions like a machine. The most impressive Medieval machines were clocks; so scientists sought the “the clockwork” that explained the behavior of things. We do not suppose that clocks have any experience or subjectivity; certainly, they have no feelings or purposes. They are matter in motion, and the task of science is to explain what makes the motions occur as they do.

Modern science was and is brilliantly successful. Again and again, it predicted what had not been thought to be explicable apart from the introduction of natural or divine purposes. It success was amazing that moderns put science on a pedestal. It was recognized that scientific knowledge had a definitiveness that had been totally lacking before. Of course, there was always more to study, but the assumption took hold that in time science could explain everything. When Darwin showed that we are part of nature, it seemed that the human soul or consciousness could also be explained.

This meant that in fact there is nothing but matter in motion. Ethics, values, morality, purposes, feelings, etc., etc. are fluff. They can be explained along with everything else as science advances. And science does advance. With its advance comes a vast improvement in technology and thus in the control of nature. Modernity is thus a vast improvement over what came before. That there has been progress can no longer be questioned.

This modern understanding of modern science has now become a major obstacle to progress when we understand progress as improving the lot and security of the human species. The occasional recognition of this fact leads to asking whether in fact the Cartesian view of nature as purely material is in fact needed by science, or even compatible with scientific finding. It seems not to work well not only in explaining conscious experience but also in explaining the nature and behavior of the quanta of which supposed matter is composed.

Interestingly, it turns out “matter” does not appear in the actual writings of science. The closest equivalent is “mass”. But not all the entities studied by science have mass. Few deny the existence of light, but light has no mass. Apparently if mass is what we mean by matter then matter is only one part of the natural world studied by physics.

Physics offers us a better candidate for universality. It is “energy”. Now for the most part “mass” and “energy” are convertible into each other. But we noted that light has no mass. Yet it has energy. Clearly the physical world consists of units of energy. One might think that this makes little metaphysical difference, but in fact the concept of “energy” is very different from the concept of “matter.” Energy cannot be pushed and pulled in the way we think of matter as being moved. Energy suggests agency, whereas matter requires some external act in order to change location or speed.

Furthermore, it is not so difficult to think of human conscious experience also embodying energy. Just as evolution should lead us to suppose, the line between human experience and other parts of nature is no longer so sharp. We noted that materialist views of nature lead to either a dualism of matter and consciousness or a monism of matter in which no one can actually believe. Science supports the abandonment of the Cartesian view of nature.

Today’s science is showing us more and more about nature that does not fit with materialism. Information has become a central concept. Animals and even plants seem to behave intelligently and purposefully. Unicellular organisms respond to human emotions. Rejecting materialism and adopting organic models opens the door to including much in science that had been rejected on a priori grounds rather than because of evidence.

Indeed, our more openminded study of what we used to call primitive people now reveals that on many counts they were wiser than we. In the West we slaughtered many women who practiced ancient medicine that involves psychological as well as physical elements. In fact, they were better healers than the modern doctors who were more “scientific”. We now routinely use placebos to give some recognition to the role of subjective feelings that modernity still excludes from having efficient causality. We find that “primitive” people can gain knowledge of the location of animals, for example, that we regard as impossible.

I am saying little that most readers will find improbable. But the dominance of modern thought in our culture keeps all of this at the fringes. The truth is that indigenous communities have beliefs and practices that are far superior to ours in terms of developing a sustainable society. At the fringes a few people are telling us this. But the dominance of modern thought blocks any significant cultural assimilation.

We are taught that our knowledge and understanding are far superior to that of indigenous people. The truth is that we do know a great many facts about the universe that they did not know. We can develop many machines they did not have. We can reshape nature in ways they could not. But an equal truth is that they understood how to live in a sustainable relation to nature. They understood that human beings are part of a community of subjects rather than simply a collection of objects so that our relations to other, both human and nonhuman, are subject to subject.

Have we progressed? Yes, in some respects. Have we regressed? Yes, in some respects. But to accept the latter as having any truth at all is to reject modernity. Such rejection is urgent.

Perhaps even more urgent is the rejection of the late modern belittling of all questions about better and worse. This is the natural result of materialism, but only when human life is included in the world of matter in motion. That inclusion arose only after Darwin, and even then it was strongly resisted. Immanuel Kant offered a new way of understanding dualism: theoretical and practical reason. But by the middle of the twentieth century modernists judged that facts alone are important, that the facts gained by theoretical reason could explain the judgments belonging to practical reason and show that they had no importance. Science is the arbiter of facts; so science alone is truly worthy of respect.

Hence, the modern world in which we live teaches that it does not matter what people believe about the world and their role in it, that human commitment and dedication do not matter. And the same world has no hope of survival unless people are willing to sacrifice some of their priorities for the sake of more important ones. The unwillingness of modern people to even discuss such questions and their continuing to ‘solve” problems by the activities that cause them suggests to me that the modernity dominated by modern science may be the most stupid culture that has ever existed. It is a major obstacle to building an ecological civilization.

Modern Nationalism

We all take a special interest in those others who accept us as part of their group. For hundred of thousands of years our ancestors lived in tribes, and the members of those tribes identified themselves primarily in that way. Some other tribes were viewed as friendly, but others were threats. These relations could change over time, but one’s fundamental identity and loyalty did not.

With the rise of civilization, citizenship in cities took over as the primary identity and loyalty of many. There was often a close connection between ancestral tribal identity and citizenship in a city. Within a city there might be many people who were not citizens. Slavery was common and usually slaves were from other cities or from tribes that had not settled in cities.

Some cities conquered others and established empires. However, most of the citizens in the conquered cities still identified themselves primarily by their cities not in terms of the empire. On the other hand, Roman emperors worked hard to evoke loyalty to the empire and to themselves as representing the empire. When confronting threats from outside the empire, many citizens of cities other than Rome did identify themselves with the empire and its culture against barbarians. Most free people in the empire gave allegiance to Rome and its emperor without abandoning identification with the local city.

The people least willing to give full obedience to Caesar were the Jews. They thought that full loyalty could be given only to God. Although on the whole they were willing to recognize that Rome ruled politically, they distinguished religious devotion from political loyalty, and Rome did not want to allow such a distinction. Despite their weakness, they rebelled several times. To pacify them Rome gave them special privileges and exemptions but eventually drove many of them out of their homeland.

The problem was aggravated when some Jews recognized Jesus as the Messiah, Christ, or liberator, because this Jewish sect spread rapidly in the Gentile population. It did not seek to overthrow the rulers of the empire, but like the Jews, it denied Caesar ultimate loyalty or “worship”. From that time on the relation of “religion” and politics, or church and state, has been a major issue in Western society. The Roman emperors from time to time tried to stamp out this new threat to their ultimate authority, but Christianity continued to grow. As the empire began to crumble, people in many regions began to look to the church for help in meeting practical needs. The church survived the collapse of the empire and for the first time what had been a voluntary organization became also the basis of self-identification of masses of people and the most powerful institution. For a thousand years most Europeans identified themselves primarily as Christians and secondarily in terms of ethnicity and location. It was generally thought that the political rulers derived their legitimacy from the church.

Of course, power attracts many people regardless of whether it is political or religious. Although the rhetoric of the church never claimed for its ruler, supreme loyalty, practically speaking the church could be as intolerant of dissent and disloyalty as the preceding empire. Its wealth also attracted many. So viewed from the perspective of original Christian teaching, many leaders of the church were corrupted by their enjoyment of wealth and earthly power. There were many protests and eventually the protest of Luther gained powerful support from political leaders. The church split.

The habit of understanding oneself religiously remained prominent; so now many understood themselves to be Catholic or Protestant. But the political rulers had played a large role in determining whether the church in a given area would be Catholic or Protestant. After decades of fighting between Catholic and Protestant princes, they made peace with the decision that political rulers would decide the form of Christianity that would be practiced in their domains. Secular government became dominant.

This move toward regional self-determination was supported by Protestantism in another way. A strong Protestant principle was that all Christians should be able to read the Bible for themselves. However, this could not happen as long as it depended on learning a foreign language, namely, Latin. Few outside the priesthood could read it. Luther undertook to translate the Bible into German. Since the spoken language differed widely according to locale, he had to decide which form of German he would use. Because reading the Bible in German became extremely important, it created a homogeneous language that could unite people who had before spoken many diverse dialects. It also excluded others whose Germanic languages were too different for Luther’s translation to be acceptable, such as the Dutch, the Danes, and other Scandinavians. They needed their own translations.

In this way national feeling was greatly strengthened. If one read Luther’s Bible, one was a German. More and more European writings were in the vernacular, so that boundaries were established among readers. Linguistic boundaries tended to become national boundaries. National feeling became much stronger than when all European literature was in Latin. Modern nationalism was born.

This modern nationalism meant not only separating Germans from people who spoke other languages but also a drive toward uniting the German people in one country. By the eighteenth century, nationalism had fully triumphed. One was no longer primarily a Christian or a Catholic or Protestant, one was German, or French, or Spanish, or Italian. Wars were fought between nations over issues over perceived national well-being. Control of distant regions in Africa and Asia was clearly for building national empires, and rhetoric about religion played a minor role at best.

Nationalism tended to strengthen German concern for other Germans. Of course, there was hierarchy and exploitation within the Germanic world. But there was little thought of some Germans enslaving others. There was also some respect for other Europeans. So, when Europeans set out to exploit the resources of the planet and colonize much of it, they did not bring with them the slave labor that would make that exploitation possible. In order to justify annihilating or enslaving the people inhabiting other parts of the world, nationalism had to be accompanied by racism. The inhabitants of Africa, South America, and North America did not belong to the same race as Europeans. Indeed, they could be regarded as not fully human, as being human was understood in Europe. Accordingly, the rights pertaining to European individuals did not protect them. Modern civilization has been the most racist the world has seen. Nowhere has racism played a larger role than in the United States.

European nationalism led to two world wars in the twentieth century. So, in its European homeland, the dominance of modern nationalism was brought to an end by the formation of the European Economic Community. It is hard to imagine conflicts between France and Germany plunging the world into was a third time. Sadly, this has not ended the danger of international war. On the one hand national feeling continues to be a danger to peace and an obstacle to moving toward ecological civilization. On the other hand, it helps us to work against mutual antagonism among ethnic and religious groups and even races.

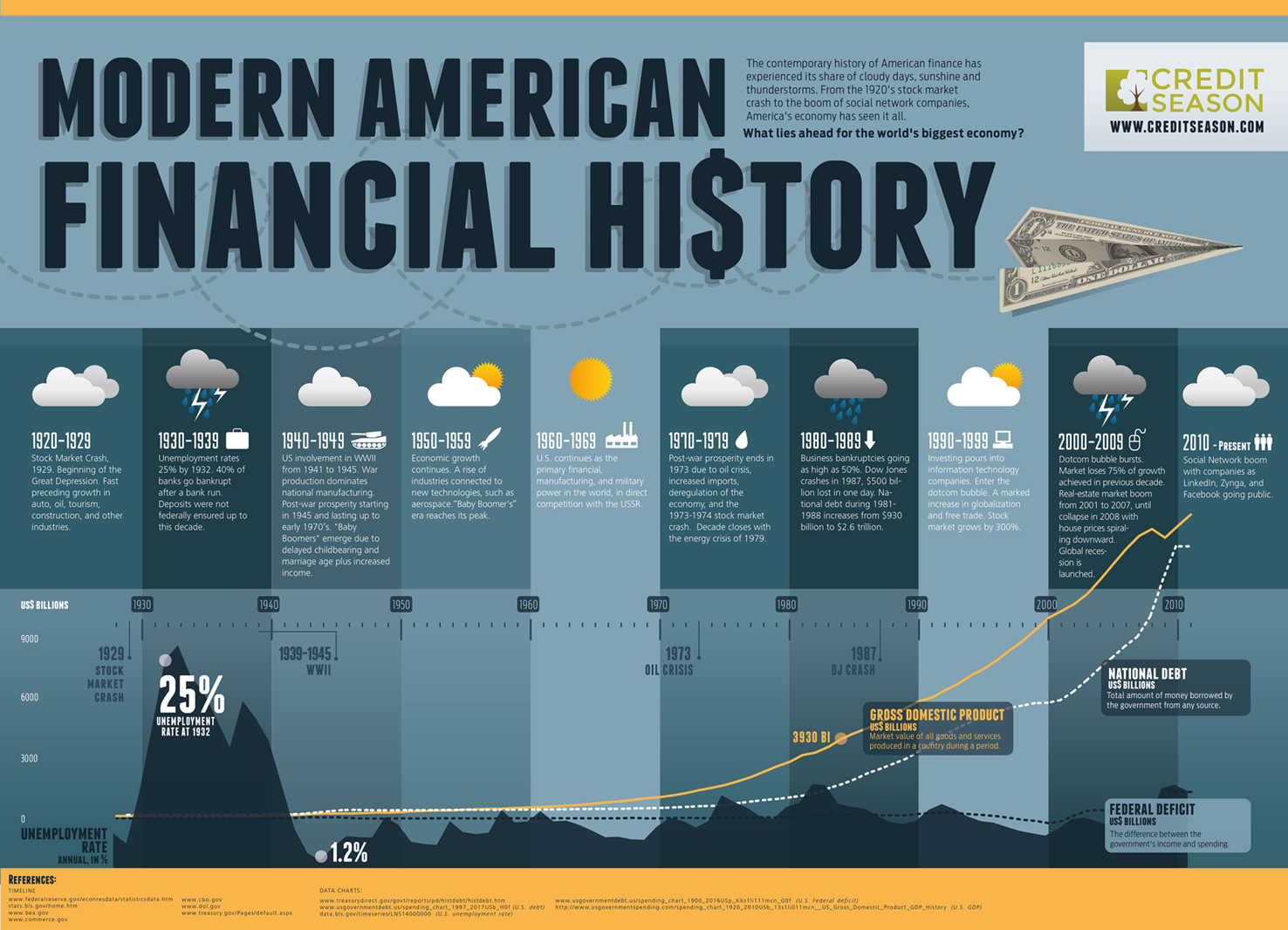

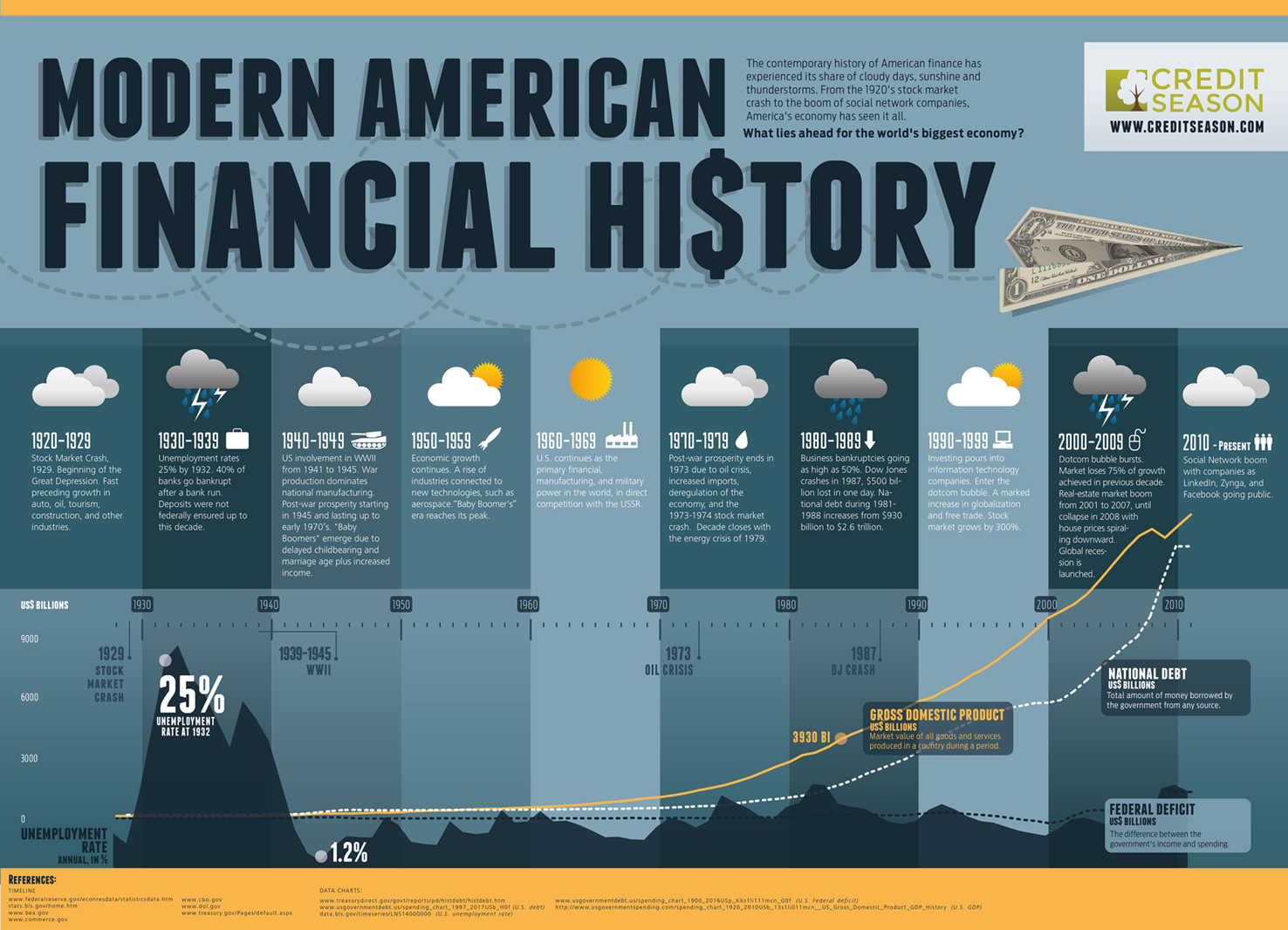

Economism

What caused the European nations to seek a closer unity was certainly the desire to avoid further wars among themselves. But it is interesting that they formulated their unity in economic terms – the European Economic Community. The clearest symbol of their unity was a common currency. Giving up control over its own money was the greatest sacrifice of sovereignty on the part of the participating nations. We saw the consequences recently when the political party committed to the will of the Greek people was forced to yield to the European banks.

Of course, the pursuit of individual wealth has played a large role in all societies, at least since the invention of money. When Jesus said one could not serve both God and wealth, this was not spoken against “economism” as a comprehensive system. That did not yet exist. During the period of Christianism there was much criticism of the clerical leadership, supposedly committed to poverty, for its luxurious lifestyle. During the modern period not only individuals, but also nations, have been devoted to the pursuit of wealth. This is a step toward “economism,” especially because it increased the power of banks in relation to nations. But nationalism gave way to economism only when national sovereignty was subordinated to the interests of the economic system. I have noted that this occurred, and was publicly announced, in the formation of the European Union.

Of course, this shift in power had been going on for some time. National rulers often needed to borrow money from bankers and this gave bankers considerable influence on policy. Few histories of Europe give adequate attention to the role of banks.

The Cold War that took over soon after World War II was partly another was between nations. However, it was in fact and often recognized to be, between two economic systems: Capitalism and Communism. Nothing of that sort had even occurred before.

The United States did not surrender sovereignty to any community of nations. Nevertheless, it may be a clearer instance of the shift from nationalism to economism than the European nations. It accepted leadership of the “Free World,” by which was meant the world that is free from Communism. To be in the service of Capitalism meant to subordinate national interests as measured in nonmonetary ways, or even GNP per capita, to effectiveness in pursuing the goals of capitalists. As long as the capitalists in question lived and worked within the nation, one could find some congruence between their interests and the pursuit of national wealth characteristic of nationalism. But the interests of capitalism were to minimize national boundaries, and the great corporations became global in scope. This was especially true of financial institutions. For the United States to serve global corporations and the global banking system, often at the expense of the American people has been a dramatic expression of the shift from nationalism to economism.

Americans who are unhappy with this development are told that this is a democracy so that if they want to return to nationalism they have only to elect representatives who will do so. But this is misleading because of another dimension of economism. In our society one must have a lot of money to mount a serious campaign for Congress or the presidency. A few people have been able to get elected without funding from the major corporations or banks or billionaires. But thus far, they have always been a small minority. Most elected officials are indebted to people of wealth and wealthy institutions. These also control the media and the educational system. Whereas democracy works well where people know those for whom they vote or at least other people who know them, representative democracy offers little resistance to the controllers of wealth. When we “democratize” other countries, they are likely to serve global capitalism rather than their own people.

For a short time after World War II, American capitalism seemed to be dominated by industrial corporations. But fairly rapidly, real power shifted from the industrial world to the financial institutions. Of course, much of the time, the interests of industry and finance largely coincide. Both aim to reduce the power of national governments to restrict business and the flow of capital. But in the “free world,” private finance controls the money supply and has a more direct power over politics than does industry.

In the long run financiers would benefit from intact eco-systems and a world with plenty of topsoil and oceans that supported lots of fish. But they have been schooled by economists who focus only on increasing market activity. Even continuing the present level of economic activity is extremely likely to make the planet uninhabitable. Its general increase speeds the coming of utter catastrophe. Nothing is more important than to end the actual reign of economism, and that will not happen unless its domination of popular thinking as well as scholarly theory are ended.

Modern Defense

One adage that is used to cover a great many absurdities is that the best defense is a skillful offense. All individual and all nations are justified in defending themselves against the attack of others. What is allowable or desirable is a matter of dispute. There are those who call for only nonviolent defense. This may mean that an individual accepts serious injury or death rather than injure or kill another person. But there have been instances when skillful use of nonviolent defense has accomplished a great deal more than the use of violence against a far more powerful adversary.

We Americans, however, can safely assume that our Department of Defense is not discussing such matters. Indeed, judging by the official story of what happened on 9/11, it seems not to devote much time and effort to protecting the buildings and lives of Americans, violently or otherwise. All evidence points to the primary interest in extending military and political control over the entire planet, what is called “full sector dominance.” In short, we act as if the only, or at least, the best way to “defend” ourselves is to attack and control everyone who does not serve us, which means, as explained above, does not serve the Western financial system.

In order for Americans to be willing to be heavily taxed to support this imperialist enterprise, they must be persuaded that it is indeed financed for the sake of the security of American lives and property. That is, what the word “defense” is ordinarily supposed to mean. Accordingly, almost any sum of money can be demanded for “defense” with little or no opposition in Congress. To be accused of being soft on defense is assumed to be the kiss of death, politically speaking. Few things are more important for reducing our destruction of the life system on the planet than redirecting government expenditures from global imperialism to the well being of people, especially, of course, American people and the natural world. Understanding that our expenditures for “defense” actually make our lives and well being more precarious would be a first step toward the exercise of common sense.

The deceptive use of “defense” goes farther. Thus far it has thus far prevented auditing the Department of Defense. It is highly probable that large sums are siphoned off to enrich the rich, and that defense contracts are not entirely directed to serving military needs efficiently. In short, powerful people have much to conceal.

Suspicion is heightened by a remarkable feature of the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon. The part of the Pentagon at which it was directed was the section where defense records were kept. Congress had finally decided on an audit, which then became impossible.

I have focused on the Department of Defense. The situation is similar, perhaps worse, with the FBI and the CIA. These two are supposed to be defending us. They, together with the Congress that funds them so generously, think that we are enemies of our own defense and so must be carefully reigned in. The freedoms of which we brag and being taken from us in the name of security.

If half of the resources now provided to the “security establishment” were spent on working for peace, justice, and prosperity along with improving global ecosystems, there might be a chance for the healthy survival of civilization. But currently there is no discussion of any reduction in what we spend on “defense” and “security” or any assessment of its actual achievements. “Defense” and “security” sound great. So, we throw more money at them, guaranteeing widespread loss and suffering.

American Exceptionalism

Earlier I discussed nationalism, and what I say there applies to the American case. However, because of the extreme importance to the planet as a whole of how Americans think of themselves, I am returning to this topic. Much of what I say about American exceptionalism can be paralleled in other countries. It is natural to evaluate all by the standards of your own culture, and when you do that you are likely to find that your culture excels, that in some ways important to you, it is unique, that is, an exception.

I grew up in Japan, and there is no question that there are unique features, very attractive features, in Japanese culture. Further, their view of themselves tends to divinize their emperor, thus reinforcing their uniqueness. Over the millennia no foreign army had invaded Japan. Japanese exceptionalism led to the belief that the lot of anyone ruled by the emperor was superior, so that its conquest of Korea and Manchuria, and the great expansion of its empire in East the Japanese military was invincible. The willingness of the Japanese to die for the emperor would enable them to defeat any enemy. In the end, of course, they were defeated despite their remarkable attitude and commitment.

Spiritually and culturally the adjustment to the possibility of being conquered was painful and difficult. I am sure that the sense of their own uniqueness has not disappeared, but whatever is left of it takes less dangerous forms. Indeed, Japanese have much be proud of, and I think pride in positive accomplishments is healthy. Part of its current uniqueness is the intensity with which it supports peace.

Unfortunately, American exceptionalism is more like Japanese exceptionalism before World War II than like current Japanese exceptionalism. Americans tend to think that our goals are beneficial to those we control. They think of the United States as committed to democracy and human rights and as promoting these all around the world.

Like the self-image of many countries, there is some truth in this. The American Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution completed by the first ten amendments, inspire people all of the world to aim at democracy and human rights. Our success in liberating ourselves from British rule with these goals led to emulation elsewhere. We were not alone in believing ourselves to be in the lead in these matters.

Our view that when we made the decisions for other people, they benefited also had some historical basis. The American occupation of Japan under MacArthur’s control was excellent for the Japanese people in many respects. He broke up the conglomerates that had excessive political and economic power. He broke up large farms and gave ownership to those who had worked them. He got the Japanese to adopt a pacifist constitution. He helped to humanize the emperor without destroying the imperial system. Human rights were emphasized along with democratic governance.

The United States has not always treated immigrants well. Nevertheless, it has done a remarkable job of taking people of many nationalities and creating a unified nation. Religious freedom and cultural diversity are allowed without fragmenting the body politic. Despite the recent losses in the name of security, I write critically about my country without fear of punishment. There is much about the United States of which we can be proud, some of it truly exceptional.

Our problem is much like that of Japan before World War II. We are so sure of our virtue and of the benefits we bestow on others, that we are blind to much that is happening. We spend more on our military than the rest of the nations combined, and so consider ourselves invincible, and do not notice that we are already losing ground. Even though we know that we have troops all over the world we do not consider ourselves an imperial power.

The history of our country that we learn in school is essentially celebratory, so we simply do not notice the dark side of our history and of our current policies. If any other countries acted as we act, we would consider it inexcusable and see to it that they were severely sanctioned. Consider, for example, how we would react if Russia engaged in drone warfare anywhere. But because it is we who are doing it, and we know that our motives are pure and our actions for the sake of people everywhere, we support our own practice. We are not told how the countries where we kill people in this way feel about it and derivatively, about us.

Nations that do not recognize the evil they do in the eyes of the world are not making themselves more secure. We need to free ourselves from erroneous or one-sided understandings of our history and current actions. Only a people who know who they really have been and are can be trusted to lead the world wisely.

So, who are we? What happened in our history that we ignore? This is a large topic. I will mention only a few points. First, from the arrival of the first settlers until today we have been in constant imperial expansion. One of the crimes of which we accused the British, justifying our revolt, was the effort to protect the indigenous people from our genocidal advance. Once we rid ourselves of British rule that advance continued and has not ceased even today.

Second, our country’s economy was built to a large extent on slave labor. Of course, everyone knows that slavery is a blot on our record, but our emphasis in recalling our history is that we freed the slaves. They and their continued exploitation tend to drop from history until Martin Luther King again forced attention.

Third, a major part of our foreign policy dealt with Latin America. While we celebrate the extension of our great nation from sea to shining sea, we pay little attention, not only to the genocide of indigenous people but to the theft of land from Mexico. Meanwhile our “Monroe doctrine” may have helped some Latin American countries gain independence from Europe, but it sucked them into our orbit of economic exploitation. The most decorated soldier in the U.S. Army, General Smedley Darlington Butler, after frequent battles in Latin America, finally understood that all his killing and leading U.S. soldiers to death was for the sake of U.S. corporate profits. He wrote War is a Racket, and devoted the rest of his life to sharing this understanding with the American people, but the truth he exposed has not found its way into our collective consciousness.

In Latin American, we frequently destroyed democratic governments in favor of military regimes that took orders from us. This is continuing to happen today. In my youth I rejoiced that I was not a citizen of one of those bad European colonial powers. The truth, of course, is that our overall record is one of the worst. It provides no basis at all for others to trust our intentions. When we realize that our military operations are also today in the service of corporations, now especially international financial corporations, we have every reason to withdraw support from established U.S. policy. It is time to recognize we are one nation among others, with our strengths and weaknesses, but with no mandate to rule the world.

The University

The discussion of American exceptionalism suggests that a standard American education gives a dangerously one-sided picture of American history. We understand that this is almost inevitable. A major function of schooling has been to turn immigrants from many nations and cultures into American citizens. All history writing is selective. To write a text book on American history for such a purpose will always lead to selections favorable to American self-appreciation. But we suppose that the leaders of the future will go on to college and there acquire more accurate knowledge.

As with so many widely held suppositions, there is some truth to this. In a college or university history department there will be a number of courses going into great detail on some segment of American history. If one majors in American history and takes many of these courses, one will certainly understand that the popular view is seriously mistaken. But it unlikely that the department will help much in developing an alternative overview. In contemporary universities, the goal is not to develop comprehensive views of what has occurred and its meaning for orienting us today. It is to acquire accurate factual information about particular events. This tends to leave the historical basis for American exceptionalism little changed even for many specialists. And, of course, the number of students who specialize in American history is very small.

I begin with this as an example of how American universities do not fulfill the expectations that many outsiders hold for them. Since these expectations are of important human functions, until we recognize that universities are about something else, we will leave these functions unfulfilled. There are some things that modern universities do well. They should be congratulated and appreciated. But meeting the world’s greatest needs is not among them. Either universities must change, or we must find other ways of educating, or we have little chance of “saving the world.” This is recognized by the title of a book written by a famous educator to university professors, Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time.

He makes it clear that universities hire professors to do research on limited topics and pass the information gained and the research methods on to their students.

Our greatest universities call themselves “value-free research universities.” Being free of values means in part being free of prejudices, open to the evidence. But it also means that values are considered unimportant, and this judgment of unimportance is transmitted to students. This makes the “modern university”, one that became normative only after World War II, unique in history. “Saving the world” is a value, I think it is a very important value that should inform our whole educational system. But discussion of this possibility is excluded from the modern university. Given the many possible topics to be researched, the decision is not made on any judgment of importance for the human species. Often in fact it is made because funding is available for that. When one brings no other values to the table, in a time of economism, money is likely to determine what is done.

The incentive for attending a university today is usually the expectation of improving job prospects, judged by salaries, that is money. Although the intention of the university is to serve the rapid increase of known facts, which facts are made known, and even how they are formulated, tends to be determined by money. Unfortunately, the research for which money is available is more likely to serve the profits of corporations than the sustainability of human life.

In the second and third sections of the paper I talked about the rigidities of the academy in relation to metaphysics or worldview. I claimed that the evidence gained by university research called for revision of the metaphysics it assumes. I repeat that charge. Universities were once places where questions about assumptions could be asked. They were, in other words, places supportive of intellectual activity. Today they are not. If intellectual reflection were encouraged, I feel quite sure that the commitment to a seventeenth-century philosophy would give way. That could open the door to an interest in wisdom, that is helpful guidance with regard to the pressing issues of personal, social, and national life. I am confident that the current threats to human life would be recognized and that our educational system would be reconceived to help us rather than to block interest in the most important questions.