A Personal Introduction

As of today there is one week left from completing four quarter-term college classes before starting the next term of classes. For those in my area who were interested I had encouraged them to join me in reading the poetry of Wendell Berry, an environmentalist, anti-industrialist, activist, and author. I had read his biography of short stories last fall in his book, "That Distant Land," and I suspect he will be as profound this time around in his poetry as he was in his prose last year.

Today, as I attended an Aldo Leopold seminar we ended class with a short walk around an adjoining preserve enjoying the warm spring weather while embracing the many new growing things beginning to emerge. Our host was an ecological biologist who invited the preserve's land manager last week, and resource educationalist today, to co-host with him of Leopold's life ethic as he developed from an industrial mindset of usury and utilitarianism to perceiving the then unseen flora and fauna biotic web of interconnected life in all its complexities. In simpler terms we know this as "the circle of life" aka the Disney film, "Lion King."

Of course, had he known of the early 20th century philosopher Alfred North Whitehead and his work on process philosophy in the early 1900s this would have helped him immensely. However, let us not fault Aldo as the entire corpus of cosmology had by then been disregarded and forgotten nearly two hundred years ago after Immanuel Kant (c1724-1804) and Soren Kirkegaard's (c.1813-1855) summary cosmological work engaging what the ancients knew to how it was understood in their late enlightenment centuries. From their observations philosophy took several directions across the European and Western continents.

Be that as it may, process philosophy has evolved to include many new forms of cosmology including process ecology. Yet this tool Aldo did not have when studying forestry at Yale University under America's first forester and conservationist, Gifford Pinchot. This he would have to learn on his own as he moved from post to post examining and re-examining what he had been taught from differing eyes and viewpoints. Actually, had we as a nation listened to the native Americans whom we disregarded as ignorant savages we would have learned about nature's centrality much more quickly, and I believe, with a much more thorough appreciation, empathy and love for the land we have not loved, destroyed and plowed under as a simple thing unworthy of care and appreciation

Alas, our history abounds with societal / cultural shortsightedness even as our recent years of abusive politics and Christian form of religion has displayed contempt for non-majorities and non-nationals we use and throw away. Human history has not been so very kind to those different from us in color, complexion, thought or speech. Nor have our passionate presumptions been true guides for conduct and civilization which usually have proven wrong, misguided, and ultimately harmful.

Be that as it may, as we grow older, those of us who are willing to unlearn what we think we know to relearn what may become a fuller comprehension of life are the better for it. Aldo Leopold was one of those late disciples even as I suspect John Muir, Henry David Theoreau, and a host of other early ecologists who similarly learned to unlearn perceptions and relearn wisdom. As we know, this happens more commonly than we care to admit with people from all walks and experiences of life. To some, this whole being and life process becomes more profound than for others. It is more complete, more expressive, even more expansive. It can upset an entire life when relizing the errors one is making in judgment, contact, or perception. As a simple example, I would point to the many testimonies from young to old who come to Jesus when finally perceiving what his atoning death and resurrection really means to this life we live. Like the renewing rains of winter's end spring comes to a life in need of growing, birthing, blooming, and regenerating future lives ahead of itself.

Lastly, I have put together a very, very brief introduction from another contributing source portraying the lives and passions of those early conservationists of the past mid-American century. I think of them as America's first generation of environmental apostles speaking the gospel of nature to a modern society which had lost its hearing and its ears to the songbird on the wing, the whisper of the pine in the winds, and how one thing affects another thing so delicately as to affect all things. Follow the link below to discover what these men and women had to unlearn to be able to see aright again.

R.E. Slater

March 10, 2010

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-933712046-5bb39fb3c9e77c002603ebe2.jpg) |

| Marco Bottigelli / Getty Images |

12 Environmentalists You Should Know

by Marc Lallanilla

Updated November 15, 2019

Environmentalists have had a big impact on our lives, but most people can't name one famous environmentalist. Here's a list of 12 influential scientists, conservationists, ecologists, and other rabble-rousing leaders who have been central founders and builders of the green movement.

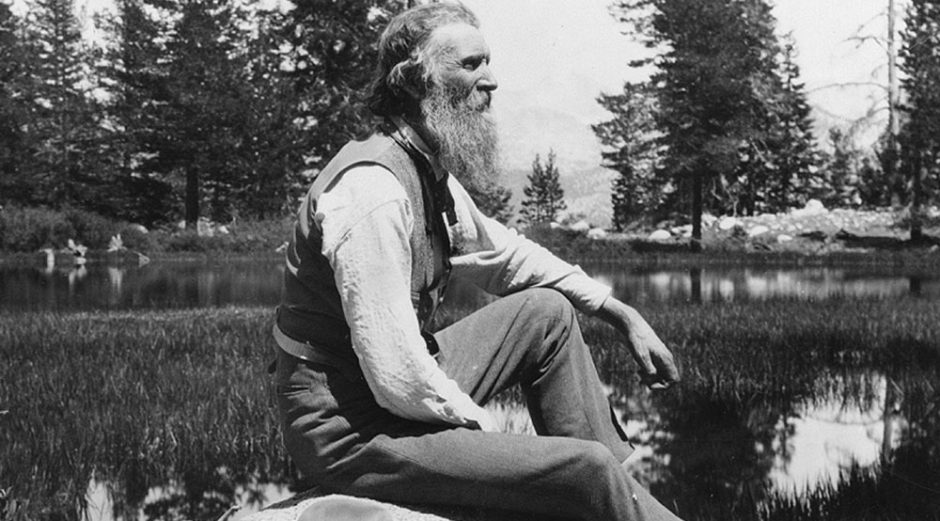

John Muir, Naturalist and Writer

|

| Conservationist John Muir |

John Muir (1838–1914) was born in Scotland and emigrated to Wisconsin as a young boy. His lifelong passion for hiking began as a young man when he hiked to the Gulf of Mexico. Muir spent much of his adult life wandering in—and fighting to preserve—the wilderness of the western United States, especially California. His tireless efforts led to the creation of Yosemite National Park, Sequoia National Park, and millions of other conservation areas. Muir was a strong influence on many leaders of his day, including Theodore Roosevelt. In 1892, Muir and others founded the Sierra Club "to make the mountains glad."

Rachel Carson, Scientist and Author

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-carson-GettyImages-577685719-58b8c22b3df78c353c1e0c8e.jpg) |

| Ecologist Rachel Carson | Photo: JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/ Getty Images |

Rachel Carson (1907–1964) is regarded by many as the founder of the modern environmental movement. Born in rural Pennsylvania, she went on to study biology at Johns Hopkins University and Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory. After working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carson published "The Sea Around Us" and other books. Her most famous work, however, was 1962's controversial "Silent Spring," in which she described the devastating effect that pesticides were having on the environment. Though pilloried by chemical companies and others, Carson's observations were proven correct, and pesticides like DDT were eventually banned.

Edward Abbey, Author and Monkey-Wrencher

|

| Conservationist Edward Abbey |

Edward Abbey (1927–1989) was one of America's most dedicated—and most outrageous—environmentalists. Born in Pennsylvania, he is best known for his passionate defense of the deserts of America's Southwest. After working for the National Park Service in what is now Arches National Park in Utah, Abbey wrote "Desert Solitaire," one of the seminal works of the environmental movement. His later book, "The Monkey Wrench Gang," gained notoriety as an inspiration for the radical environmental group Earth First!—a group that has been accused of eco-sabotage by some, including many mainstream environmentalists.

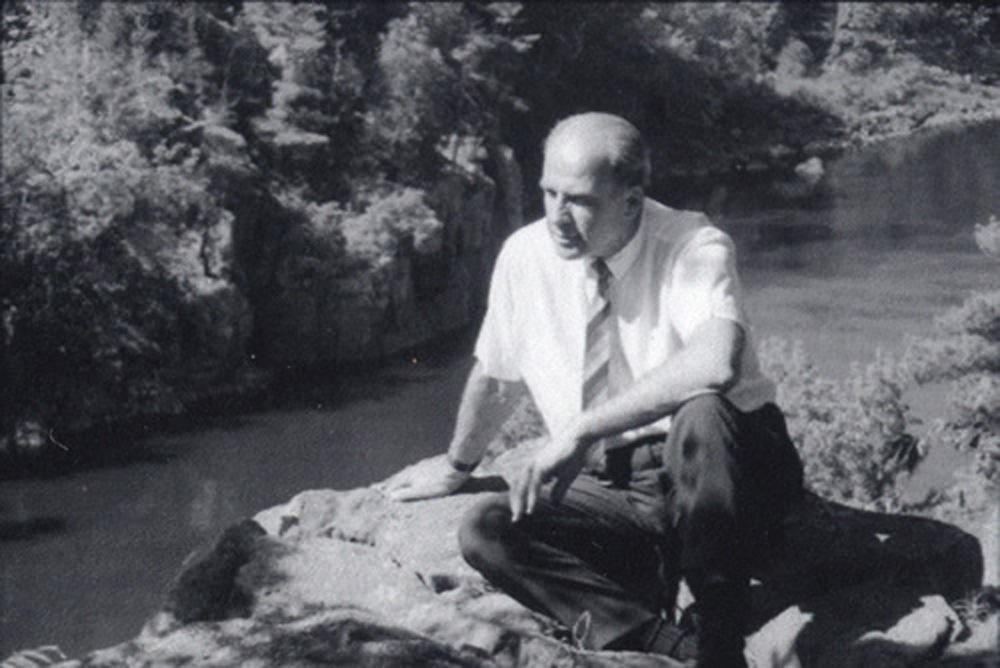

Aldo Leopold, Ecologist and Author

|

| Conservationist Aldo Leopold of The Land Ethic |

Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) is considered by some to be the godfather of wilderness conservation and of modern ecologists. After studying forestry at Yale University, he worked for the U.S. Forest Service. Though he was originally asked to kill bears, cougars, and other predators on federal land because of demands of protesting local ranchers, he later adopted a more holistic approach to wilderness management. His best-known book, "A Sand County Almanac," remains one of the most eloquent pleas for the preservation of wilderness ever composed.

Julia Hill, Environmental Activist

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Julia-Hill-GettyImages-539723776-58b961705f9b58af5c449137.jpg) |

| Conservationist Julia Hill | Photo: Andrew Lichtenstein/Getty Images |

Julia "Butterfly" Hill (born 1974) is one of the most committed environmentalists alive today. After nearly dying in an auto accident in 1996, she dedicated her life to environmental causes. For almost two years, Hill lived in the branches of an ancient redwood tree (which she named Luna) in northern California to save it from being cut down. Her tree-sit became an international cause célèbre, and Hill remains involved in environmental and social causes.

Henry David Thoreau, Author and Activist

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Henry-David-Thoreau-GettyImages-AB30213-58b961ea3df78c353cd86ebb.jpg) |

| Henry David Thoreau | Photo: FPG/Getty Images |

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) was one of America's first philosopher-writer-activists, and he is still one of the most influential. In 1845, Thoreau—disillusioned with much of contemporary life—set out to live alone in a small house he built near the shore of Walden Pond in Massachusetts. The two years he spent living a life of utter simplicity was the inspiration for "Walden, or A Life in the Woods," a meditation on life and nature that is considered a must-read for all environmentalists. Thoreau also wrote an influential political piece called "Resistance to Civil Government (Civil Disobedience)" that outlined the moral bankruptcy of overbearing governments.

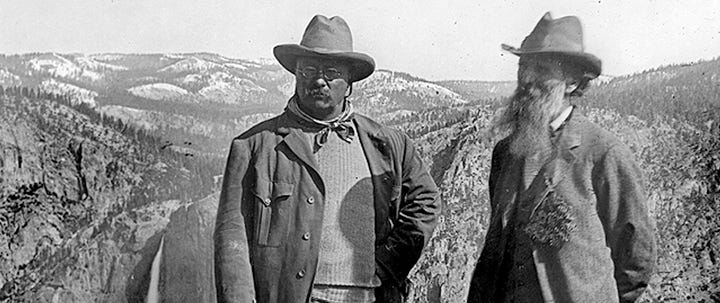

Theodore Roosevelt, Politician and Conservationist

|

| President Theodore Roosevelt with Conservationist John Muir |

It might surprise some that a famed big-game hunter would make it onto a list of environmentalists, but Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) was one of the most active champions of wilderness preservation in history. As governor of New York, he outlawed the use of feathers as clothing adornment in order to prevent the slaughter of some birds. While president of the United States (1901–1909), Roosevelt set aside hundreds of millions of wilderness acres, actively pursued soil and water conservation, and created over 200 national forests, national monuments, national parks, and wildlife refuges.

Gifford Pinchot, Forester and Conservationist

|

| Gifford Pinchot, Forester and Conservationist |

Gifford Pinchot (1865–1946) was the son of a timber baron who later regretted the damage he had done to America's forests. At his insistence, Pinchot studied forestry for many years and was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to develop a plan for managing America's western forests. That career continued when Theodore Roosevelt asked him to lead the U.S. Forest Service. His time in office was not without opposition, however. He publicly battled John Muir over the destruction of wilderness tracts like Hetch Hetchy in California, while also being condemned by timber companies for closing off land to their exploitation.

Chico Mendes, Conservationist and Activist

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Chico-Mendes-GettyImages-530239202-58b966753df78c353cda7158.jpg) |

| Conservationist Chico Mendes | Photo: Alex Robinson/Getty Images |

Chico Mendes (1944–1988) is best known for his efforts at saving the rainforests of Brazil from logging and ranching activities. Mendes came from a family of rubber harvesters who supplemented their income by sustainably gathering nuts and other rainforest products. Alarmed at the devastation of the Amazon rainforest, he helped to ignite international support for its preservation. His activities, however, drew the ire of powerful ranching and timber interests —Mendes was murdered by cattle ranchers at age 44.

Wangari Maathai, Political Activist and Environmentalist

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Wangari-Maathai-GettyImages-525237988-58b966aa5f9b58af5c469d35.jpg) |

| Conservationist Wangari Maathai | Photo: Wendy Stone / Getty Images |

Wangari Maathai (1940–2011) was an environmental and political activist in Kenya. After studying biology in the United States, she returned to Kenya to begin a career that combined environmental and social concerns. Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement in Africa and helped to plant over 30 million trees, providing jobs to the unemployed while also preventing soil erosion and securing firewood. She was appointed Assistant Minister in the Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources, and in 2004 Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize while continuing to fight for the rights of women, the politically oppressed, and the natural environment.

Gaylord Nelson, Politician and Environmentalist

|

| Gaylord Nelson, Politician and Environmentalist |

No other name is more associated with Earth Day than that of Gaylord Nelson (1916–2005). After returning from World War II, Nelson began a career as a politician and environmental activist that was to last the rest of his life. As governor of Wisconsin, he created an Outdoor Recreation Acquisition Program that saved about one million acres of parkland. He was instrumental in the development of a national trails system (including the Appalachian Trail) and helped pass the Wilderness Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and other landmark environmental legislation. He is perhaps best known as the founder of Earth Day, which has become an international celebration of all things environmental.

David Brower, Environmental Activist

|

| Envrionmental Activist David Brower |

David Brower (1912–2000) has been associated with wilderness preservation since he began mountain climbing as a young man. Brower was appointed the Sierra Club's first executive director in 1952. Over the next 17 years, membership grew from 2,000 to 77,000, and the group won many environmental victories. His confrontational style, however, got Brower fired from the Sierra Club—he nonetheless went on to found the groups Friends of the Earth, the Earth Island Institute, and the League of Conservation Voters.

![Whitehead Word Book: A Glossary with Alphabetical Index to Technical Terms in Process and Reality (Toward Ecological Civilization Book 8) by [Cobb Jr, John B]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/411paEaBBDL.jpg)