St. Patrick's Bad Analogies

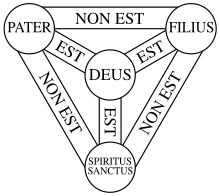

The problem with using analogies to explain the Holy Trinity is

that you always end up confessing some ancient heresy.

The History of Saint Patrick's Day - Animated Narration for Kids

St. Patrick's Day | Bet You Didn't Know ...

6 Things You Didn't Know about St. Patrick's Day | British Pathé

St Patrick's Day 2014 #IrelandInspires

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed, also known as Pseudo-Athanasian Creed or Quicunque Vult (also Quicumque Vult), is a Christian statement of belief focused on Trinitarian doctrine and Christology. The Latin name of the creed, Quicunque vult, is taken from the opening words, "Whosoever wishes". The creed has been used by Christian churches since the sixth century. It is the first creed in which the equality of the three persons of the Trinity is explicitly stated. It differs from the Nicene-Constantinopolitan and Apostles' Creeds in the inclusion of anathemas, or condemnations of those who disagree with the creed (like the original Nicene Creed).

Widely accepted among Western Christians, including the Roman Catholic Church and some Anglican churches, Lutheran churches (it is considered part of Lutheran confessions in the Book of Concord), and ancient, liturgical churches generally, the Athanasian Creed has been used in public worship less and less frequently, but part of it can be found as an "Authorized Affirmation of Faith" in the recent (2000) Common Worship liturgy of the Church of England [Main Volume page 145].[1][2] It was designed to distinguish Nicene Christianity from the heresy of Arianism. Liturgically, this Creed was recited at the Sunday Office of Prime in the Western Church; it is not in common use in the Eastern Church. The creed has never gained acceptance in liturgy among Eastern Christians since it was considered as one of many unorthodox fabrications that contained the Filioque clause. Today, the Athanasian Creed is rarely used even in the Western Church. When used, one common practice is to use it once a year on Trinity Sunday.[3]

Origin

A medieval account credited Athanasius of Alexandria, the famous defender of Nicene theology, as the author of the Creed. According to this account, Athanasius composed it during his exile in Rome and presented it to Pope Julius I as a witness to his orthodoxy. This traditional attribution of the Creed to Athanasius was first called into question in 1642 by Dutch Protestant theologian G.J. Voss,[4] and it has since been widely accepted by modern scholars that the creed was not authored by Athanasius,[5] that it was not originally called a creed at all,[6] nor was Athanasius' name originally attached to it.[7] Athanasius' name seems to have become attached to the creed as a sign of its strong declaration of Trinitarian faith. The reasoning for rejecting Athanasius as the author usually relies on a combination of the following:

- The creed originally was most likely written in Latin, while Athanasius composed in Greek.

- Neither Athanasius nor his contemporaries ever mention the Creed.

- It is not mentioned in any records of the ecumenical councils.

- It appears to address theological concerns that developed after Athanasius died (including the filioque).

- It was most widely circulated among Western Christians.[2][8]

The use of the creed in a sermon by Caesarius of Arles, as well as a theological resemblance to works by Vincent of Lérins, point to Southern Gaul as its origin.[5] The most likely time frame is in the late fifth or early sixth century AD – at least 100 years after Athanasius. The theology of the creed is firmly rooted in the Augustinian tradition, using exact terminology of Augustine's On the Trinity (published 415 AD).[9][incomplete short citation] In the late 19th century, there was a great deal of speculation about who might have authored the creed, with suggestions including Ambrose of Milan, Venantius Fortunatus, and Hilary of Poitiers, among others.[10] The 1940 discovery of a lost work by Vincent of Lérins, which bears a striking similarity to much of the language of the Athanasian Creed, have led many to conclude that the creed originated either with Vincent or with his students.[11] For example, in the authoritative modern monograph about the creed, J.N.D. Kelly asserts that Vincent of Lérins was not its author, but that it may have come from the same milieu, namely the area of Lérins in southern Gaul.[12] The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Athanasian Creed date from the late 8th century.[13]

Content

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The Athanasian Creed is usually divided into two sections: lines 1–28 addressing the doctrine of the Trinity, and lines 29–44 addressing the doctrine of Christology.[14]Enumerating the three persons of the Trinity (i.e., Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), the first section of the creed ascribes the divine attributes to each individually. Thus, each person of the Trinity is described as uncreated (increatus), limitless (Immensus), eternal (æternus), and omnipotent (omnipotens).[15] While ascribing the divine attributes and divinity to each person of the Trinity, thus avoiding subordinationism, the first half of the Athanasian Creed also stresses the unity of the three persons in the one Godhead, thus avoiding a theology of tritheism. Furthermore, although one God, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct from each other. For the Father is neither made nor begotten; the Son is not made but is begotten from the Father; the Holy Spirit is neither made nor begotten but proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque).

The text of the Athanasian Creed is as follows:

in Latin

|

Quicumque vult salvus esse, ante omnia opus est, ut teneat

catholicam fidem: Quam nisi quisque integram inviolatamque servaverit, absque

dubio in aeternum peribit. Fides autem catholica haec est: ut unum Deum in

Trinitate, et Trinitatem in unitate veneremur. Neque confundentes personas,

neque substantiam separantes. Alia est enim persona Patris alia Filii, alia

Spiritus Sancti: Sed Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti una est divinitas,

aequalis gloria, coeterna maiestas. Qualis Pater, talis Filius, talis [et]

Spiritus Sanctus. Increatus Pater, increatus Filius, increatus [et] Spiritus

Sanctus. Immensus Pater, immensus Filius, immensus [et] Spiritus Sanctus.

Aeternus Pater, aeternus Filius, aeternus [et] Spiritus Sanctus. Et tamen non

tres aeterni, sed unus aeternus. Sicut non tres increati, nec tres immensi,

sed unus increatus, et unus immensus. Similiter omnipotens Pater, omnipotens

Filius, omnipotens [et] Spiritus Sanctus. Et tamen non tres omnipotentes, sed

unus omnipotens. Ita Deus Pater, Deus Filius, Deus [et] Spiritus Sanctus. Et

tamen non tres dii, sed unus est Deus. Ita Dominus Pater, Dominus Filius,

Dominus [et] Spiritus Sanctus. Et tamen non tres Domini, sed unus [est]

Dominus. Quia, sicut singillatim unamquamque personam Deum ac Dominum

confiteri christiana veritate compellimur: Ita tres Deos aut [tres] Dominos

dicere catholica religione prohibemur. Pater a nullo est factus: nec creatus,

nec genitus. Filius a Patre solo est: non factus, nec creatus, sed genitus.

Spiritus Sanctus a Patre et Filio: non factus, nec creatus, nec genitus, sed

procedens. Unus ergo Pater, non tres Patres: unus Filius, non tres Filii:

unus Spiritus Sanctus, non tres Spiritus Sancti. Et in hac Trinitate nihil

prius aut posterius, nihil maius aut minus: Sed totae tres personae

coaeternae sibi sunt et coaequales. Ita, ut per omnia, sicut iam supra dictum

est, et unitas in Trinitate, et Trinitas in unitate veneranda sit. Qui vult

ergo salvus esse, ita de Trinitate sentiat.

Sed necessarium est ad aeternam salutem, ut incarnationem quoque

Domini nostri Iesu Christi fideliter credat. Est ergo fides recta ut credamus

et confiteamur, quia Dominus noster Iesus Christus, Dei Filius, Deus

[pariter] et homo est. Deus [est] ex substantia Patris ante saecula genitus:

et homo est ex substantia matris in saeculo natus. Perfectus Deus, perfectus

homo: ex anima rationali et humana carne subsistens. Aequalis Patri secundum

divinitatem: minor Patre secundum humanitatem. Qui licet Deus sit et homo,

non duo tamen, sed unus est Christus. Unus autem non conversione divinitatis

in carnem, sed assumptione humanitatis in Deum. Unus omnino, non confusione

substantiae, sed unitate personae. Nam sicut anima rationalis et caro unus

est homo: ita Deus et homo unus est Christus. Qui passus est pro salute nostra:

descendit ad inferos: tertia die resurrexit a mortuis. Ascendit ad [in]

caelos, sedet ad dexteram [Dei] Patris [omnipotentis]. Inde venturus [est]

judicare vivos et mortuos. Ad cujus adventum omnes homines resurgere habent

cum corporibus suis; Et reddituri sunt de factis propriis rationem. Et qui

bona egerunt, ibunt in vitam aeternam: qui vero mala, in ignem aeternum. Haec

est fides catholica, quam nisi quisque fideliter firmiterque crediderit,

salvus esse non poterit.

|

English translation[16]

|

Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that

he hold the catholic faith. Which faith except every one do keep whole and

undefiled; without doubt he shall perish everlastingly. And the catholic

faith is this: That we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity;

Neither confounding the Persons; nor dividing the Essence. For there is one

Person of the Father; another of the Son; and another of the Holy Ghost. But

the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, is all one; the

Glory equal, the Majesty coeternal. Such as the Father is; such is the Son;

and such is the Holy Ghost. The Father uncreated; the Son uncreated; and the

Holy Ghost uncreated. The Father unlimited; the Son unlimited; and the Holy

Ghost unlimited. The Father eternal; the Son eternal; and the Holy Ghost

eternal. And yet they are not three eternals; but one eternal. As also there

are not three uncreated; nor three infinites, but one uncreated; and one

infinite. So likewise the Father is Almighty; the Son Almighty; and the Holy

Ghost Almighty. And yet they are not three Almighties; but one Almighty. So

the Father is God; the Son is God; and the Holy Ghost is God. And yet they

are not three Gods; but one God. So likewise the Father is Lord; the Son

Lord; and the Holy Ghost Lord. And yet not three Lords; but one Lord. For

like as we are compelled by the Christian verity; to acknowledge every Person

by himself to be God and Lord; So are we forbidden by the catholic religion;

to say, There are three Gods, or three Lords. The Father is made of none; neither

created, nor begotten. The Son is of the Father alone; not made, nor created;

but begotten. The Holy Ghost is of the Father and of the Son; neither made,

nor created, nor begotten; but proceeding. So there is one Father, not three

Fathers; one Son, not three Sons; one Holy Ghost, not three Holy Ghosts. And

in this Trinity none is before, or after another; none is greater, or less

than another. But the whole three Persons are coeternal, and coequal. So that

in all things, as aforesaid; the Unity in Trinity, and the Trinity in Unity,

is to be worshipped. He therefore that will be saved, let him thus think of

the Trinity.

Furthermore, it is necessary to everlasting salvation; that he

also believe faithfully the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ. For the

right Faith is, that we believe and confess; that our Lord Jesus Christ, the

Son of God, is God and Man; God, of the Substance [Essence] of the Father;

begotten before the worlds; and Man, of the Substance [Essence] of his

Mother, born in the world. Perfect God; and perfect Man, of a reasonable soul

and human flesh subsisting. Equal to the Father, as touching his Godhead; and

inferior to the Father as touching his Manhood. Who although he is God and

Man; yet he is not two, but one Christ. One; not by conversion of the Godhead

into flesh; but by assumption of the Manhood into God. One altogether; not by

confusion of Substance [Essence]; but by unity of Person. For as the

reasonable soul and flesh is one man; so God and Man is one Christ; Who

suffered for our salvation; descended into hell; rose again the third day

from the dead. He ascended into heaven, he sitteth on the right hand of God

the Father Almighty, from whence he will come to judge the living and the

dead. At whose coming all men will rise again with their bodies; And shall

give account for their own works. And they that have done good shall go into

life everlasting; and they that have done evil, into everlasting fire. This

is the catholic faith; which except a man believe truly and firmly, he cannot

be saved.

|

The Christology of the second section is more detailed than that of the Nicene Creed, and reflects the teaching of the First Council of Ephesus (431) and the definition of the Council of Chalcedon (451). The Athanasian Creed uses the term substantia (a Latin translation of the Nicene homoousios: 'same being' or 'consubstantial') not only with respect to the relation of the Son to the Father according to his divine nature, but also says the Son is substantia of his mother Mary according to his human nature.

The Creed's wording thus excludes not only Sabellianism and Arianism, but the Christological heresies of Nestorianism and Eutychianism. A need for a clear confession against Arianism arose in western Europe when the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, who had Arian beliefs, invaded at the beginning of the 5th century.

The final section of this Creed also moved beyond the Nicene (and Apostles') Creeds in making negative statements about the people's fate: "They that have done good shall go into life everlasting: and they that have done evil into everlasting fire." This caused considerable debate in England in the mid-nineteenth century, centred on the teaching of Frederick Denison Maurice.

Uses

Composed of 44 rhythmic lines, the Athanasian Creed appears to have been intended as a liturgical document – that is, the original purpose of the creed was to be spoken or sung as a part of worship. The creed itself uses the language of public worship, speaking of the worship of God rather than the language of belief ("Now this is the catholic faith: We worship one God"). In the Catholic Church in medieval times, this creed was recited following the Sunday sermon or at the Sunday Office of Prime.[17] The creed was often set to music and used in the place of a Psalm.

Early Protestants inherited the late medieval devotion to the Athanasian Creed, and it was considered to be authoritative in many Protestant churches. The statements of Protestant belief (confessional documents) of various Reformers commend the Athanasian Creed to their followers, including the Augsburg Confession, the Formula of Concord, the Second Helvetic Confession, the Belgic Confession, the Bohemian Confession and the Thirty-nine Articles.[18] A metric version titled "Quicumque vult", with a musical setting, was published in The Whole Booke of Psalmes printed by John Day in 1562. Among modern Lutheran and Reformed churches adherence to the Athanasian Creed is prescribed by the earlier confessional documents, but the creed does not receive much attention outside of occasional use – especially on Trinity Sunday.[17]

In Reformed circles, it is included (for example) in the Christian Reformed Churches of Australia's Book of Forms (publ. 1991). However, it is rarely recited in public worship.

In the successive Books of Common Prayer of the reformed Church of England, from 1549 to 1662, its recitation was provided for on 19 occasions each year, a practice which continued until the nineteenth century, when vigorous controversy regarding its statement about 'eternal damnation' saw its use gradually decline. It remains one of the three Creeds approved in the Thirty-Nine Articles, and is printed in several current Anglican prayer books (e.g. A Prayer Book for Australia (1995)). As with Roman Catholic practice, its use is now generally only on Trinity Sunday or its octave. The Episcopal Church based in the United States has never provided for its use in worship, but added it to its Book of Common Prayer for the first time in 1979, where it is included in small print in a reference section entitled "Historical Documents of the Church."[19]

In Roman Catholic churches, it was traditionally said at Prime on Sundays when the Office was of the Sunday. The 1911 reforms reduced this to Sundays after Epiphany and Pentecost, and on Trinity Sunday, except when a commemoration of a Double feast or a day within an Octave occurred. The 1960 reforms further reduced its use to once a year, on Trinity Sunday. It has been effectively dropped from the Catholic liturgy since the Second Vatican Council. It is however maintained in the Forma Extraordinaria, per the decree Summorum Pontificum, and also in the rite of exorcism, both in the Forma Ordinaria and the Forma Extraordinaria of the Roman Rite.

In Lutheranism, the Athanasian Creed is—along with the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds—one of the three ecumenical creeds placed at the beginning of the 1580 Book of Concord, the historic collection of authoritative doctrinal statements (confessions) of the Lutheran Church. It is still used in the liturgy on Trinity Sunday.

A common visualisation of the first half of the Creed is the Shield of the Trinity.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Saint Patrick

(Redirected from St Patrick)

"Patrick of Ireland" redirects here. For the 14th-century writer, see Master Patrick of Ireland. For other uses, see Saint Patrick (disambiguation).

| Saint Patrick | |

|---|---|

Popular devotional depiction of Saint Patrick

| |

| Born | Great Britain |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches Eastern Orthodox Church Anglicanism Lutheranism |

| Major shrine | Armagh, Northern Ireland Glastonbury Abbey, England |

| Feast | 17 March (Saint Patrick's Day) |

| Patronage | Ireland, Nigeria, Montserrat, Archdiocese of New York, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark, Boston, Rolla, Missouri, Loíza, Puerto Rico, Murcia (Spain), Clann Giolla Phádraig, engineers, paralegals, Archdiocese of Melbourne; invoked against snakes, sins[1] |

Saint Patrick (Latin: Patricius; Irish: Pádraig [ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ]) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, along with saints Brigit of Kildare and Columba. He is also venerated in the Anglican Communion, the Old Catholic Church and in the Eastern Orthodox Church as equal-to-apostles and the Enlightener of Ireland.[2]

The dates of Patrick's life cannot be fixed with certainty but there is broad agreement that he was active as a missionary in Ireland during the second half of the 5th century. Early medieval tradition credits him with being the first bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland, and they regard him as the founder of Christianity in Ireland, converting a society practising a form of Celtic polytheism. He has been generally so regarded ever since, despite evidence of some earlier Christian presence in Ireland.

According to the Confessio of Patrick, when he was about 16, he was captured by Irish pirates from his home in Britain, and taken as a slave to Ireland, looking after animals, where he lived for six years before escaping and returning to his family. After becoming a cleric, he returned to northern and western Ireland. In later life, he served as a bishop, but little is known about the places where he worked. By the seventh century, he had already come to be revered as the patron saint of Ireland.

Saint Patrick's Day is observed on 17 March, the supposed date of his death. It is celebrated inside and outside Ireland as a religious and cultural holiday. In the dioceses of Ireland, it is both a solemnity and a holy day of obligation; it is also a celebration of Ireland itself.

Sources

Two Latin works survive which are generally accepted to have been written by St. Patrick. These are the Declaration (Latin: Confessio)[3] and the Letter to the soldiers of Coroticus (Latin: Epistola),[4] from which come the only generally accepted details of his life.[5] The Declaration is the more biographical of the two. In it, Patrick gives a short account of his life and his mission. Most available details of his life are from subsequent hagiographies and annals, and these are now not accepted without detailed criticism.

Name

The only name that Patrick uses for himself in his own writings is Pātricius, which gives Old Irish Pátraic and Modern Irish Pádraig ([ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ]), English Patrick and Welsh Padrig.

Hagiography records other names he is said to have borne. Tírechán's seventh-century Collectanea gives: "Magonus, that is, famous; Succetus, that is, god of war; Patricius, that is, father of the citizens; Cothirthiacus, because he served four houses of druids."[6] "Magonus" appears in the ninth century Historia Brittonum as Maun, descending from British *Magunos, meaning "servant-lad".[6] "Succetus", which also appears in Muirchú moccu Machtheni's seventh century Life as Sochet,[6] is identified by Mac Neill as "a word of British origin meaning swineherd".[7] Cothirthiacus also appears as Cothraige in the 8th century biographical poem known as Fiacc's Hymn and a variety of other spellings elsewhere, and is taken to represent a Primitive Irish *Qatrikias, although this is disputed. Harvey argues that Cothraige "has the form of a classic Old Irish tribal (and therefore place-) name", noting that Ail Coithrigi is a name for the Rock of Cashel, and the place-names Cothrugu and Catrige are attested in Counties Antrim and Carlow.[8]

Dating

The dates of Patrick's life are uncertain; there are conflicting traditions regarding the year of his death. His own writings provide no evidence for any dating more precise than the 5th century generally. His Biblical quotations are a mixture of the Old Latin version and the Vulgate, completed in the early 5th century, suggesting he was writing "at the point of transition from Old Latin to Vulgate",[9] although it is possible the Vulgate readings may have been added later, replacing earlier readings.[10] The Letter to Coroticus implies that the Franks were still pagans at the time of writing:[11] their conversion to Christianity is dated to the period 496–508.[12]

The Irish annals for the fifth century date Patrick's arrival in Ireland at 432, but they were compiled in the mid-6th century at the earliest.[11] The date 432 was probably chosen to minimise the contribution of Palladius, who was known to have been sent to Ireland in 431, and maximise that of Patrick.[13] A variety of dates are given for his death. In 457 "the elder Patrick" (Irish: Patraic Sen) is said to have died: this may refer to the death of Palladius, who according to the Book of Armagh was also called Patrick.[13] In 461/2 the annals say that "Here some record the repose of Patrick";[14]:p. 19 in 492/3 they record the death of "Patrick, the arch-apostle (or archbishop and apostle) of the Scoti", on 17 March, at the age of 120.[14]:p. 31

While some modern historians[15] accept the earlier date of c. 460 for Patrick's death, scholars of early Irish history tend to prefer a later date, c. 493. Supporting the later date, the annals record that in 553 "the relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a shrine by Colum Cille" (emphasis added).[16] The death of Patrick's disciple Mochta is dated in the annals to 535 or 537,[16][17] and the early hagiographies "all bring Patrick into contact with persons whose obits occur at the end of the fifth century or the beginning of the sixth".[18] However, E. A. Thompson argues that none of the dates given for Patrick's death in the Annals are reliable.[19]

"Two Patricks" theory

Irish academic T. F. O'Rahilly proposed the "Two Patricks" theory [20] which suggests that many of the traditions later attached to Saint Patrick actually concerned the aforementioned Palladius, who Prosper of Aquitaine's Chronicle says was sent by Pope Celestine I as the first bishop to Irish Christians in 431. Palladius was not the only early cleric in Ireland at this time. The Irish-born Saint Ciarán of Saigir lived in the later fourth century (352–402) and was the first bishop of Ossory. Ciaran, along with saints Auxilius, Secundinus and Iserninus, are also associated with early churches in Munster and Leinster. By this reading, Palladius was active in Ireland until the 460s.[21]

Prosper associates Palladius' appointment with the visits of Germanus of Auxerre to Britain to suppress Pelagianism and it has been suggested that Palladius and his colleagues were sent to Ireland to ensure that exiled Pelagians did not establish themselves among the Irish Christians. The appointment of Palladius and his fellow-bishops was not obviously a mission to convert the Irish, but more probably intended to minister to existing Christian communities in Ireland.[22] The sites of churches associated with Palladius and his colleagues are close to royal centres of the period: Secundus is remembered by Dunshaughlin, County Meath, close to the Hill of Tara which is associated with the High King of Ireland; Killashee, County Kildare, close to Naas with links with the kings of Leinster, is probably named for Auxilius. This activity was limited to the southern half of Ireland, and there is no evidence for them in Ulster or Connacht.[23]

Although the evidence for contacts with Gaul is clear, the borrowings from Latin into Old Irish show that links with Roman Britain were many.[24] Iserninus, who appears to be of the generation of Palladius, is thought to have been a Briton, and is associated with the lands of the Uí Ceinnselaig in Leinster. The Palladian mission should not be contrasted with later "British" missions, but forms a part of them;[25] nor can the work of Palladius be uncritically equated with that of Saint Patrick, as was once traditional.[26]

Life

St. Patrick was born in Roman Britain. Calpurnius, his father, was a decurion and deacon, his grandfather Potitus a priest, from Banna Venta Berniae,[27] a location otherwise unknown,[28][29][30] though identified in one tradition as Glannoventa, modern Ravenglass in Cumbria, England; claims have been advanced for locations in both Scotland and Wales.[31][32] Patrick, however, was not an active believer. According to the Confession of St. Patrick, at the age of just sixteen Patrick was captured by a group of Irish pirates.[33] They brought him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in The Confession[33] that the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development. He explains that the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance, and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven of his sins and converted to Christianity. While in captivity, Saint Patrick worked as a shepherd and strengthened his relationship with God through prayer eventually leading him to convert to Christianity.[33]

After six years of captivity he heard a voice telling him that he would soon go home, and then that his ship was ready. Fleeing his master, he travelled to a port, two hundred miles away,[34] where he found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days sailing they landed, presumably in Britain, and apparently all left the ship, walking for 28 days in a "wilderness", becoming faint from hunger. After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar;[35] since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his prestige in the group was greatly increased. After various adventures, he returned home to his family, now in his early twenties.[36] After returning home to Britain, Saint Patrick continued to study Christianity.

Patrick recounts that he had a vision a few years after returning home:

A. B. E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of St. Patrick's vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396.[38] However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees.[39]

He studied in Europe principally at Auxerre, but is thought to have visited the Marmoutier Abbey, Tours and to have received the tonsure at Lérins Abbey. Saint Germanus of Auxerre ordained the young missionary.[40][41]

Acting on the vision, Patrick returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary.[33] According to J.B. Bury, his landing place was Wicklow, Co. Wicklow, at the mouth of the river Inver-dea, which is now called the Vartry.[42] J.B. Bury suggests that Wicklow was also the port through which Patrick made his escape after his six years captivity, though offers only circumstantial evidence to support this.[43] Tradition has it that St Patrick was not welcomed by the locals and was forced to leave to seek a more welcoming landing place further north. He rested for some days at the islands off the Skerries coast, one of which still retains the name of Inis-Patrick. The first sanctuary dedicated by St. Patrick was at Saul. Shortly thereafter Benin (or Benignus), son of the chieftain Secsnen, joined Patrick's group.[41]

Much of the Declaration concerns charges made against St. Patrick by his fellow Christians at a trial. What these charges were, he does not say explicitly, but he writes that he returned the gifts which wealthy women gave him, did not accept payment for baptisms, nor for ordaining priests, and indeed paid for many gifts to kings and judges, and paid for the sons of chiefs to accompany him. It is concluded, therefore, that he was accused of some sort of financial impropriety, and perhaps of having obtained his bishopric in Ireland with personal gain in mind.[44]

From this same evidence, something can be seen of St. Patrick's mission. He writes that he "baptised thousands of people".[45] He ordained priests to lead the new Christian communities. He converted wealthy women, some of whom became nuns in the face of family opposition. He also dealt with the sons of kings, converting them too.[46] The Confessio is generally vague about the details of his work in Ireland, though giving some specific instances. This is partly because, as he says at points, he was writing for a local audience of Christians who knew him and his work. There are several mentions of travelling around the island, and of sometimes difficult interactions with the chiefly elite. He does claim of the Irish:"Never before did they know of God except to serve idols and unclean things. But now, they have become the people of the Lord, and are called children of God. The sons and daughters of the leaders of the Irish are seen to be monks and virgins of Christ!"[47]

St. Patrick's position as a foreigner in Ireland was not an easy one. His refusal to accept gifts from kings placed him outside the normal ties of kinship, fosterage and affinity. Legally he was without protection, and he says that he was on one occasion beaten, robbed of all he had, and put in chains, perhaps awaiting execution.[48] Patrick says that he was also "many years later" a captive for 60 days, without giving details.[49]

Murchiú's life of Saint Patrick contains a supposed prophecy by the druids which gives an impression of how Patrick and other Christian missionaries were seen by those hostile to them:

- Across the sea will come Adze-head,[50] crazed in the head,

his cloak with hole for the head, his stick bent in the head.

He will chant impieties from a table in the front of his house;

all his people will answer: "so be it, so be it."[51]

The second piece of evidence that comes from Patrick's life is the Letter to Coroticus or Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus, written after a first remonstrance was received with ridicule and insult. In this, St. Patrick writes[52] an open letter announcing that he has excommunicated Coroticus because he had taken some of St. Patrick's converts into slavery while raiding in Ireland. The letter describes the followers of Coroticus as "fellow citizens of the devils" and "associates of the Scots [of Dalriada and later Argyll] and Apostate Picts".[53] Based largely on an eighth-century gloss, Coroticus is taken to be King Ceretic of Alt Clut.[54] Thompson however proposed that based on the evidence it is more likely that Coroticus was a British Roman living in Ireland.[55] It has been suggested that it was the sending of this letter which provoked the trial which Patrick mentions in the Confession.[56]

Seventh-century writings

An early document which is silent concerning Patrick is the letter of Columbanus to Pope Boniface IV of about 613. Columbanus writes that Ireland's Christianity "was first handed to us by you, the successors of the holy apostles", apparently referring to Palladius only, and ignoring Patrick.[57] Writing on the Easter controversy in 632 or 633, Cummian—it is uncertain whether this is Cumméne Fota, associated with Clonfert, or Cumméne Find—does refer to Patrick, calling him "our papa", that is, pope or primate.[58]

Two works by late seventh-century hagiographers of Patrick have survived. These are the writings of Tírechán and the Vita sancti Patricii of Muirchú moccu Machtheni.[59] Both writers relied upon an earlier work, now lost, the Book of Ultán.[60] This Ultán, probably the same person as Ultan of Ardbraccan, was Tírechán's foster-father. His obituary is given in the Annals of Ulster under the year 657.[61] These works thus date from a century and a half after Patrick's death.

Tírechán writes, "I found four names for Patrick written in the book of Ultán, bishop of the tribe of Conchobar: holy Magonus (that is, "famous"); Succetus (that is, the god of war); Patricius (that is, father of the citizens); Cothirtiacus (because he served four houses of druids)."[62]

Muirchu records much the same information, adding that "[h]is mother was named Concessa."[63] The name Cothirtiacus, however, is simply the Latinized form of Old Irish Cothraige, which is the Q-Celtic form of LatinPatricius.[64]

The Patrick portrayed by Tírechán and Muirchu is a martial figure, who contests with druids, overthrows pagan idols, and curses kings and kingdoms.[65] On occasion, their accounts contradict Patrick's own writings: Tírechán states that Patrick accepted gifts from female converts although Patrick himself flatly denies this. However, the emphasis Tírechán and Muirchu placed on female converts, and in particular royal and noble women who became nuns, is thought to be a genuine insight into Patrick's work of conversion. Patrick also worked with the unfree and the poor, encouraging them to vows of monastic chastity. Tírechán's account suggests that many early Patrician churches were combined with nunneries founded by Patrick's noble female converts.[66]

The martial Patrick found in Tírechán and Muirchu, and in later accounts, echoes similar figures found during the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity. It may be doubted whether such accounts are an accurate representation of Patrick's time, although such violent events may well have occurred as Christians gained in strength and numbers.[67]

Much of the detail supplied by Tírechán and Muirchu, in particular the churches established by Patrick, and the monasteries founded by his converts, may relate to the situation in the seventh century, when the churches which claimed ties to Patrick, and in particular Armagh, were expanding their influence throughout Ireland in competition with the church of Kildare. In the same period, Wilfred, Archbishop of York, claimed to speak, as metropolitan archbishop, "for all the northern part of Britain and of Ireland" at a council held in Rome in the time of Pope Agatho, thus claiming jurisdiction over the Irish church.[68]

Other presumed early materials include the Irish annals, which contain records from the Chronicle of Ireland. These sources have conflated Palladius and Patrick.[69] Another early document is the so-called First Synod of Saint Patrick. This is a seventh-century document, once, but no longer, taken as to contain a fifth-century original text. It apparently collects the results of several early synods, and represents an era when pagans were still a major force in Ireland. The introduction attributes it to Patrick, Auxilius, and Iserninus, a claim which "cannot be taken at face value."[70]

Legends

Patrick uses shamrock in an illustrative parable

Legend credits St. Patrick with teaching the Irish about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity by showing people the shamrock, a three-leafed plant, using it to illustrate the Christian teaching of three persons in one God.[71][72] This story first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be older. The shamrock has since become a central symbol for St Patrick's Day.

In pagan Ireland, three was a significant number and the Irish had many triple deities, a fact that may have aided St Patrick in his evangelisation efforts when he "held up a shamrock and discoursed on the Christian Trinity".[73][74] Patricia Monaghan says there is no evidence that the shamrock was sacred to the pagan Irish.[73] However, Jack Santino speculates that it may have represented the regenerative powers of nature, and was recast in a Christian context. Icons of St Patrick often depict the saint "with a cross in one hand and a sprig of shamrocks in the other".[75] Roger Homan writes, "We can perhaps see St Patrick drawing upon the visual concept of the triskele when he uses the shamrock to explain the Trinity".[76]

Patrick banishes all snakes from Ireland

The absence of snakes in Ireland gave rise to the legend that they had all been banished by St. Patrick[77] chasing them into the sea after they attacked him during a 40-day fast he was undertaking on top of a hill.[78] This hagiographic theme draws on the Biblical account of the staff of the prophet Moses. In Exodus 7:8–7:13, Moses and Aaron use their staffs in their struggle with Pharaoh's sorcerers, the staffs of each side morphing into snakes. Aaron's snake-staff prevails by consuming the other snakes.[79]

However, all evidence suggests that post-glacial Ireland never had snakes.[80] "At no time has there ever been any suggestion of snakes in Ireland, so [there was] nothing for St. Patrick to banish", says naturalist Nigel Monaghan, keeper of natural history at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, who has searched extensively through Irish fossil collections and records.[78]

Patrick's walking stick grows into a living tree

Some Irish legends involve the Oilliphéist, the Caoránach, and the Copóg Phádraig. During his evangelising journey back to Ireland from his parent's home at Birdoswald, he is understood to have carried with him an ash wood walking stick or staff. He thrust this stick into the ground wherever he was evangelising and at the place now known as Aspatria (ash of Patrick) the message of the dogma took so long to get through to the people there that the stick had taken root by the time he was ready to move on.

Patrick speaks with ancient Irish ancestors

The twelfth-century work Acallam na Senórach tells of Patrick being met by two ancient warriors, Caílte mac Rónáin and Oisín, during his evangelical travels. The two were once members of Fionn mac Cumhaill's warrior band the Fianna, and somehow survived to Patrick's time. In the work St. Patrick seeks to convert the warriors to Christianity, while they defend their pagan past. The heroic pagan lifestyle of the warriors, of fighting and feasting and living close to nature, is contrasted with the more peaceful, but unheroic and non-sensual life offered by Christianity.

Folk piety

The version of the details of his life generally accepted by modern scholars, as elaborated by later sources, popular writers and folk piety, typically includes extra details such that Patrick, originally named Maewyn Succat, was born in 387 AD in (among other candidate locations, see above) Banna venta Berniae[81] to the parents Calpernius and Conchessa. At the age of 16 in 403 AD Saint Patrick was captured and enslaved by the Irish and was sent to Ireland to serve as a slave herding and tending sheep in Dalriada.[82] During his time in captivity Saint Patrick became fluent in the Irish language and culture. After six years, Saint Patrick escaped captivity after hearing a voice urging him to travel to a distant port where a ship would be waiting to take him back to Britain.[83] On his way back to Britain Saint Patrick was captured again and spent 60 days in captivity in Tours, France. During his short captivity within France, Saint Patrick learned about French monasticism. At the end of his second captivity Saint Patrick had a vision of Victoricus giving him the quest of bringing Christianity to Ireland.[84] Following his second captivity Saint Patrick returned to Ireland and, using the knowledge of Irish language and culture that he gained during his first captivity, brought Christianity and monasticism to Ireland in the form of more than 300 churches and over 100,000 Irish baptised.[85]

According to the Annals of the Four Masters, an early-modern compilation of earlier annals, his corpse soon became an object of conflict in the Battle for the Body of St. Patrick.

Alternative interpretations

A recent alternative interpretation of Patrick's departure to Ireland suggests that as the son of a decurion he would have been obliged by Roman law to serve on the town council (curia), but chose instead to abscond from the onerous obligations of this office by fleeing abroad, as many others in his position had done in what has become known as the 'flight of the curiales'.[86] However, according to Patrick's own account, it was the raiders who brought him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years.[87] Roy Flechner also asserts the improbability of an escape from servitude and journey of the kind that Patrick purports to have undertaken. He also draws attention to the biblical allusions in Patrick's own account (e.g. the topos of freedom after six years of servitude in Exod. 21:2 or Jer. 34:14), which imply that perhaps parts of the account may not have been intended to be understood literally.[88]

Saint Patrick's crosses

Main article: List of Saint Patrick's Crosses

There are two main types of crosses associated with St. Patrick, the cross pattée and the saltire. The cross pattée is the more traditional association, while the association with the saltire dates from 1783 and the Order of St. Patrick.

The cross pattée has long been associated with St. Patrick, for reasons that are uncertain. One possible reason is that bishops' mitres in Ecclesiastical heraldry often appear surmounted by a cross pattée.[89][90] An example of this can be seen on the old crest of the Brothers of St. Patrick.[91] As St. Patrick was the founding bishop of the Irish church, the symbol may have become associated with him. St. Patrick is traditionally portrayed in the vestments of a bishop, and his mitre and garments are often decorated with a cross pattée.[92][93][94][95][96]

The cross pattée retains its link to St. Patrick to the present day. For example,it appears on the coat of arms of both the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh[97] and the Church of Ireland Archdiocese of Armagh.[98] This is on account of St. Patrick being regarded as the first bishop of the Diocese of Armagh. It is also used by Down District Council which has its headquarters in Downpatrick, the reputed burial place at St. Patrick.

Saint Patrick's Saltire is a red saltire on a white field. It is used in the insignia of the Order of Saint Patrick, established in 1783, and after the Acts of Union 1800 it was combined with the Saint George's Cross of England and the Saint Andrew's Cross of Scotland to form the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A saltire was intermittently used as a symbol of Ireland from the seventeenth century, but without reference to Saint Patrick.

It was formerly a common custom to wear a cross made of paper or ribbon on St Patrick's Day. Surviving examples of such badges come in many colours[99] and they were worn upright rather than as saltires.[100]

Thomas Dinely, an English traveller in Ireland in 1681, remarked that "the Irish of all stations and condicõns were crosses in their hatts, some of pins, some of green ribbon."[101] Jonathan Swift, writing to "Stella" of Saint Patrick's Day 1713, said "the Mall was so full of crosses that I thought all the world was Irish".[102] In the 1740s, the badges pinned were multicoloured interlaced fabric.[103] In the 1820s, they were only worn by children, with simple multicoloured daisy patterns.[103][104] In the 1890s, they were almost extinct, and a simple green Greek cross inscribed in a circle of paper (similar to the Ballina crest pictured).[105] The Irish Times in 1935 reported they were still sold in poorer parts of Dublin, but fewer than those of previous years "some in velvet or embroidered silk or poplin, with the gold paper cross entwined with shamrocks and ribbons".[106]

Saint Patrick's Bell

The National Museum of Ireland in Dublin possesses a bell (Clog Phádraig)[107][109] first mentioned, according to the Annals of Ulster, in the Book of Cuanu in the year 552. The bell was part of a collection of "relics of Patrick" removed from his tomb sixty years after his death by Colum Cille to be used as relics. The bell is described as "The Bell of the Testament", one of three relics of "precious minna" (extremely valuable items), of which the other two are described as Patrick's goblet and "The Angels Gospel". Colum Cille is described to have been under the direction of an "Angel" for whom he sent the goblet to Down, the bell to Armagh, and kept possession of the Angel's Gospel for himself. The name Angels Gospel is given to the book because it was supposed that Colum Cille received it from the angel's hand. A stir was caused in 1044 when two kings, in some dispute over the bell, went on spates of prisoner taking and cattle theft. The annals make one more apparent reference to the bell when chronicling a death, of 1356: "Solomon Ua Mellain, The Keeper of The Bell of the Testament, protector, rested in Christ."

The bell was encased in a "bell shrine", a distinctive Irish type of reliquary made for it, as an inscription records, by King Domnall Ua Lochlainn sometime between 1091 and 1105. The shrine is an important example of the final, Viking-influenced, style of Irish Celtic art, with intricate Urnes style decoration in gold and silver. The Gaelic inscription on the shrine also records the name of the maker "U INMAINEN" (which translates to "Noonan"), "who with his sons enriched/decorated it"; metalwork was often inscribed for remembrance.

The bell itself is simple in design, hammered into shape with a small handle fixed to the top with rivets. Originally forged from iron, it has since been coated in bronze. The shrine is inscribed with three names, including King Domnall Ua Lochlainn's. The rear of the shrine, not intended to be seen, is decorated with crosses while the handle is decorated with, among other work, Celtic designs of birds. The bell is accredited with working a miracle in 1044 and having been coated in bronze to shield it from human eyes, for which it would be too holy. It measures 12.5 × 10 cm at the base, 12.8 × 4 cm at the shoulder, 16.5 cm from base to shoulder, 3.3 cm from shoulder to top of handle and weighs 1.7 kg.[110]

Saint Patrick's Breastplate

Main article: Saint Patrick's Breastplate

Saint Patrick's Breastplate is a lorica, or hymn, which is attributed to Saint Patrick during his Irish ministry in the 5th century.

Saint Patrick and Irish identity

St. Patrick features in many stories in the Irish oral tradition and there are many customs connected with his feast day. The folklorist Jenny Butler[111] discusses how these traditions have been given new layers of meaning over time while also becoming tied to Irish identity both in Ireland and abroad. The symbolic resonance of the St. Patrick figure is complex and multifaceted, stretching from that of Christianity’s arrival in Ireland to an identity that encompasses everything Irish. In some portrayals, the saint is symbolically synonymous with the Christian religion itself. There is also evidence of a combination of indigenous religious traditions with that of Christianity, which places St Patrick in the wider framework of cultural hybridity. Popular religious expression has this characteristic feature of merging elements of culture. Later in time, the saint becomes associated specifically with Catholic Ireland and synonymously with Irish national identity. Subsequently, St. Patrick is a patriotic symbol along with the colour green and the shamrock. St. Patrick's Day celebrations include many traditions that are known to be relatively recent historically, but have endured through time because of their association either with religious or national identity. They have persisted in such a way that they have become stalwart traditions, viewed as the strongest "Irish traditions".

Sainthood and modern remembrance

17 March, popularly known as St. Patrick's Day, is believed to be his death date and is the date celebrated as his Feast Day.[112] The day became a feast day in the Catholic Church due to the influence of the Waterford-born Franciscan scholar Luke Wadding, as a member of the commission for the reform of the Breviary in the early part of the seventeenth century.[113]

For most of Christianity's first thousand years, canonisations were done on the diocesan or regional level. Relatively soon after the death of people considered very holy, the local Church affirmed that they could be liturgically celebrated as saints. As a result, St. Patrick has never been formally canonised by a Pope; nevertheless, various Christian churches declare that he is a Saint in Heaven (he is in the List of Saints). He is still widely venerated in Ireland and elsewhere today.[114]

St. Patrick is honoured with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) and with a commemoration on the calendar of Evangelical Lutheran Worship, both on 17 March. St. Patrick is also venerated in the Orthodox Church, especially among English-speaking Orthodox Christians living in Ireland, the UK and in the USA.[115] There are Orthodox icons dedicated to him.[116]

St. Patrick is said to be buried at Down Cathedral in Downpatrick, County Down, alongside St. Brigid and St. Columba, although this has never been proven. Saint Patrick Visitor Centre is a modern exhibition complex located in Downpatrick and is a permanent interpretative exhibition centre featuring interactive displays on the life and story of Saint Patrick. It provides the only permanent exhibition centre in the world devoted to Saint Patrick.[117]

Places associated with Saint Patrick

- When captured by raiders, there are two theories as to where Patrick was enslaved. One theory is that he herded sheep in the countryside around Slemish. Another theory is that Patrick herded sheep near Killala Bay, at a place called Fochill.

- Saul, County Down (from Irish: Sabhall Phádraig, meaning "Patrick's barn")[118]

- It is claimed that Patrick founded his first church in a barn at Saul, which was donated to him by a local chieftain called Dichu. It is also claimed that Patrick died at Saul or was brought there between his death and burial. Nearby, on the crest of Slieve Patrick, is a huge statue of Saint Patrick with bronze panels showing scenes from his life.

- Muirchu moccu Machtheni, in his highly mythologised seventh-century Life of Patrick, says that Patrick lit a Paschal fire on this hilltop in 433 in defiance of High King Laoire. The story says that the fire could not be doused by anyone but Patrick, and it was here that he explained the holy trinity using the shamrock.

- Croagh Patrick, County Mayo (from Irish: Cruach Phádraig, meaning "Patrick's stack")[119]

- It is claimed that Patrick climbed this mountain and fasted on its summit for the forty days of Lent. Croagh Patrick draws thousands of pilgrims who make the trek to the top on the last Sunday in July.

- Lough Derg, County Donegal (from Irish: Loch Dearg, meaning "red lake")[120]

- It is claimed that Patrick killed a large serpent on this lake and that its blood turned the water red (hence the name). Each August, pilgrims spend three days fasting and praying there on Station Island.

- It is claimed that Patrick founded a church here and proclaimed it to be the most holy church in Ireland. Armagh is today the primary seat of both the Catholic Church in Ireland and the Church of Ireland, and both cathedrals in the town are named after Patrick.

- Downpatrick, County Down (from Irish: Dún Pádraig, meaning "Patrick's stronghold")[121]

- It is claimed that Patrick was brought here after his death and buried in the grounds of Down Cathedral.

Other places named after Saint Patrick include:

- Ardpatrick, County Limerick (from Irish: Ard Pádraig, meaning "high place of Patrick")[122]

- Patrick Water (Old Patrick Water), Elderslie, Renfrewshire. from Scots' Gaelic "AlltPadraig" meaning Patrick's Burn [123][124][125][126]

- Patrickswell or Toberpatrick, County Limerick (from Irish: Tobar Phádraig, meaning "Patrick's well")[127]

- St Patrick's Chapel, Heysham

- St Patrick's Island, County Dublin

- Old Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton, Scotland from "Cill Phàdraig," Patrick's Church, a claimant to his birthplace

- St Patrick's Isle, off the Isle of Man

- St. Patricks, Newfoundland and Labrador, a community in the Baie Verte district of Newfoundland

- Llanbadrig (church), Ynys Badrig (island), Porth Padrig (cove), Llyn Padrig (lake), and Rhosbadrig (heath) on the island of Anglesey in Wales

- Templepatrick, County Antrim (from Irish: Teampall Phádraig, meaning "Patrick's church")[128]

- St Patrick's Hill, Liverpool, on old maps of the town near to the former location of "St Patrick's Cross"[129]

- Patreksfjörður, Iceland

- Parroquia San Patricio y Espiritu Santo. Loiza, Puerto Rico. The site was initially mentioned in 1645 as a chapel. The actual building was completed by 1729, is one of the oldest churches in the Americas and today represents the faith of many Irish immigrants that settled in Loiza by the end of the 18th century. Today it is a museum.

In literature

- Robert Southey wrote a ballad called Saint Patrick's Purgatory, based on popular legends surrounding the saint's name.

- Patrick is mentioned in a 17th-century ballad about "Saint George and the Dragon"

- Stephen R. Lawhead wrote the fictional Patrick: Son of Ireland based on the life of the celebrated Saint.[130]