|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

Many thanks to Jay McDaniel for assembling the thoughts and accompanying post from process theologian John Cobb along with Jay's own diligence and observations on Process Christianity and the help it brings to enlivening the Christian faith, message, and community of Jesus to the world we live in today.

R.E. Slater

January 20, 2020

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Process Theology and

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ref: Open Horizons

Seven Similarities

Process Theology and

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ref: Open Horizons

Seven Similarities

Martin Luther King, Jr. was not a process theologian in any formal way. Still, his approach to religion and life resembles that of many process theologians in seven respects:

- King had an appreciation of liberal theology as he learned it at Crozer Theology School, preferring it to Barth's biblicist approach. In this he resembles process thinkers with their apprecation of natural theology.

- King wrote his dissertation on Tillich and Weiman, critiquing both for not understanding for not affirming God is a person with consciousness and intentions, thus preferring the liberal theology of Boston Personalism. In this he resembles many process thinkers with their emphasis on a personal God who "feels the feelings" of all living beings and responds with love by offering fresh possibilities for wisdom, compassion and creativity.

- King believed in God and evolution, understanding God as a source of novelty in the universe. In this he resembles process theologians with their appreciation of a God who works cosmically and not just humanly.

- King believed in non-violence. In this he is close to process theologians with their emphasis on persuasion not coercion.

- King recognized that the non-violent life includes how people think and feel as well as how they act. In this he resembles Gandhi and process theologians, who likewise recognize the important of subjectivity in human life (emotions, intentions, subjective aims, subjective forms) and who, as committed to persuasation not coercion, recognize that the life of relational love has an inner dimension.

- King believed that the religious life rightly requires helping build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, egalitarian, and spiritually satisfying with no one left behind. In this he shares the hope of process theologians, who likewise seek such communities and add that are part of what is involved in "ecological civlizations."

- King was an ecumenist, interested in inter-faith harmony. In this he resembles process theologians who, whether Christian or Jewish or Muslim or Hindu or Buddhist, are likewise drawn to interfaith cooperation and mutual transformation through dialogue.

- King would disagree with process theologians in their rejection of creatio ex nihilo, emphasizing instead that God is self-limiting rather than limited by the power of the world. But he was not very interested in debates on such matters, having his mind and heart focused on what he took to be more important matters: e.g. social justice.

*Note: Process theology generally agrees on the idea of creatio ex continua. - res

Encyclopedia.com - Keith Ward, Theologian

The term creatio continua refers to God's continuing creative activity throughout the history of the universe. In a sense, most theologians accept creatio continua, since creation is the dependence of the whole of space-time on God. But more traditional views hold that because God is timeless and immutable, there is only one divine creative act, which originates the whole of space-time from first to last. Those who speak of creatio continua think of creation taking place in many successive acts, partly in response to events in time. Thus, at any particular time God's creation has not been completed, and the future is partly open, in some theological views, even for God.

Creatio ex nihilo (Latin for "creation from nothing") refers to the view that the universe, the whole of space-time, is created by a free act of God out of nothing, and not either out of some preexisting material or out of the divine substance itself. This view was widely, though not universally, accepted in the early Christian Church, and was formally defined as dogma by the fourth Lateran Council in 1215. Creatio ex nihilo is now almost universally accepted by Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Indian theism generally holds that the universe is substantially one with God, though it is usually still thought of as a free and unconstrained act of God.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

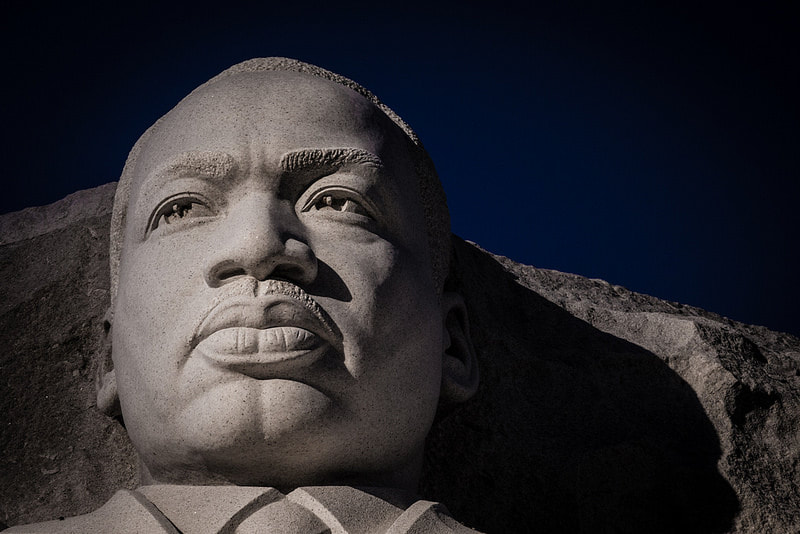

Martin Luther King Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Christian minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the Civil Rights Movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. Born in Atlanta, Georgia, King is best known for advancing civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi.

King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and in 1957 became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). With the SCLC, he led an unsuccessful 1962 struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. He helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. In 1965, he helped organize the Selma to Montgomery marches. The following year, he and the SCLC took the movement north to Chicago to work on segregated housing. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards poverty and the Vietnam War. He alienated many of his liberal allies with a 1967 speech titled "Beyond Vietnam". J. Edgar Hoover considered him a radical and made him an object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963 on. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital liaisons and reported on them to government officials, and on one occasion mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. Sentenced to 99 years in prison for King's murder, effectively a life sentence as Ray was 41 at the time of conviction, Ray served 29 years of his sentence and died from hepatitis in 1998 while in prison.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971; the holiday was enacted at the federal level by legislation signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and a county in Washington was rededicated for him. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

The remainder of this post is attributed to Open Horizons - res

The remainder of this post is attributed to Open Horizons - res

|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

Lessons from a Baptist Preacher

Life is a process

potentially guided by

an arc of Love and Justice

and a personal God

whose heart is the arc

and whose hands are our own.

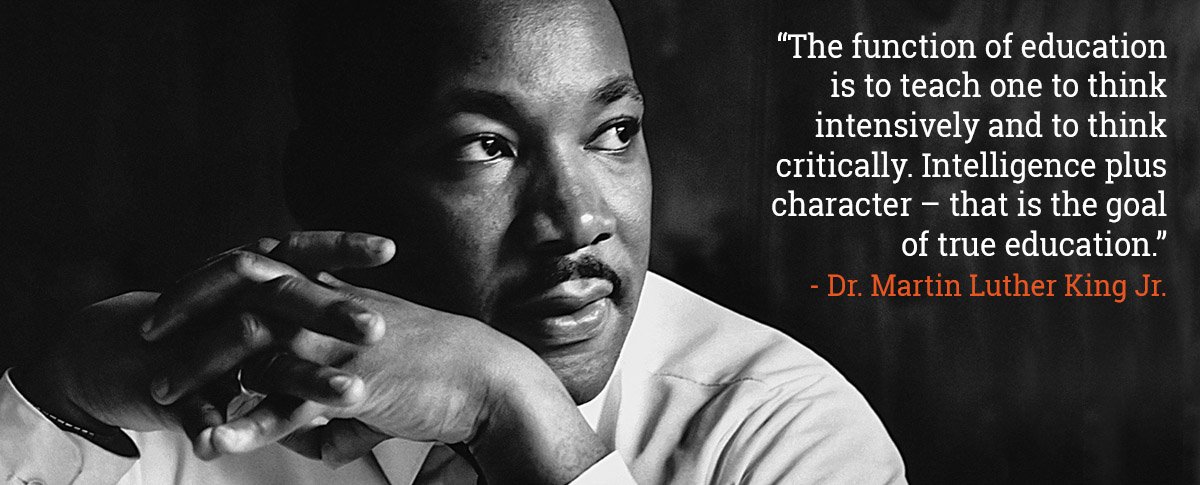

“I am many things to many people; Civil Rights leader, agitator, trouble-maker, and orator, but in the quiet resources of my heart, I am fundamentally a clergyman, a Baptist preacher,” he said. “This is my being and my heritage. … The Church is my life and I have given my life to the Church.”

- Martin Luther King, Jr., 1965: from the Black Church to India: The Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr.

|

| Martin Luther King, Jr. |

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Early Theology

King's Understanding of God and Evolution

in his own words

With "the rise of the scientific interpretation of the origin of the world and the emergence of the theory of evolution many thought that the basic Christian view of creation was totally destroyed. This belief might be right in seeing the invalidity of the older view of a first creation, but it is wrong in thinking that all views of creations were destroyed with the rise of scientific interpretation. It seems quite possible to get an adequate religious view of the world in the light of emergent evolution and cosmic theism. Is it not possible for God to be working through the evolutionary process? May it not be the God is creating from eternity? Emergent evolution says essentially that in the evolutionary process there is a continuous incoming of the new. The question arises, from whence comes this emergence of new elements in the evolutionary process. The religious man answers, with a degree of assurance, that God is the source of the new emergents. In other words, God is working through the evolutionary process."

- Martin Luther King, Jr.: Written Exam at Crozer Theological Seminary, sometime between 1949 and 1950.

- Martin Luther King, Jr.: Written Exam at Crozer Theological Seminary, sometime between 1949 and 1950.

King's Appreciation of Liberal Theology

"I have been greatly influenced by liberal theology,

maintaining a healthy respect for reason

and a strong belief in the immanence

as well as the transcendence of God."

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

About King's Dissertation on Tillich and Wieman

"King passed his final doctoral examination in February 1954, and his dissertation outline was approved by Boston University’s graduate school on 9 April, shortly before he accepted the call to pastor Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. King’s letter of acceptance to Dexter’s congregation specified that he be “granted an allowance of time to complete my work at Boston University,” though he would be “able to fill the pulpit at least once or twice per month.” He also asked that the church cover his expenses during the completion of his dissertation, “including traveling expenses” (Papers 2:260).

King chose to focus his dissertation research on Tillich and Wieman due to their status as influential religious thinkers and as representatives of divergent views on the nature of God. King’s comparison of Tillich’s and Wieman’s concepts of God reflected his adherence to personalism, which proceeds from the belief that God possesses a personality and can therefore have a relationship with human beings. King’s analysis of Tillich’s and Wieman’s theological concepts as “unsatisfactory” and “inadequate as philosophical and religious world-views” followed from his belief that God was a living force, “responsive to the deepest yearnings of the human heart; this God both evokes and answers prayer” (Papers 2:532; 533; 512). He found that both Wieman and Tillich rejected the conception of a personal God, which resulted in “a rejection of the rationality, goodness, and love of God in the full sense of the words. An impersonal ‘being-itself’ or ‘creative event’ cannot be rational or good, for these attributes are of personality” (Papers 2:506). In the end, King pointed out the two theologians’ views of God are not “basically sound” because they “render real religious experience impossible” (Papers 2:532)."

Research and Education Institute

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Boston Personalism and Whiteheadian Theology

by John B. Cobb, Jr. for Phillip Fletcher

If, in my quest to see whether, or to what extent, what is now known can support, or even allow, the faith of my youth, I had gone to Boston University instead of the University of Chicago, I would no doubt have become a Personalist. When I encountered Personalist theology in my reading, I found it, in general, quite satisfying. Indeed, it was much more fully and systematically developed than anything that the Divinity School of Chicago offered. While at the Divinity School I imagined teaching philosophy of religion to college students, and I remember thinking that I would use a book of Brightman as the text.

If I had not studied Whitehead, I would probably not have asked the questions to which Personalist philosophy’s answers were less developed than Hartshorne’s or, especially, Whitehead’s thought. Probably, when I did begin to encounter the questions not as adequately dealt with in Personalist philosophy, I would have felt that the needed development was possible without giving up the philosophy overall.

However, I now consider myself fortunate to have come to Personalism after having encountered Whitehead rather than the other way. Personalism developed in the context of German Idealism. That developed from Immanuel Kant’s acceptance of the limitations Hume had shown in British empiricism. The key point was that Hume showed that when we examine very carefully what we actually see, we cannot discover any causal relation. It seems, then that the causal relations, so important to the sciences, must be imposed on the data by habitual expectations generated by repeated occurrences of sequences.

Kant carried this further and, noting the limitations of what we actually see in relation to our scientific understanding of the world, he attributed the construction of the scientific world to the human mind. The whole German Idealist tradition adopted this view, which gave a decisive role to the constructive activity of the mind. Personalism developed as one expression of this tradition.

As a Whiteheadian, when confronted with the acute problems resulting from the way we had treated nature, I was embarrassed by how little attention I had given theologically to the natural world. But change was easy. The philosophy I was using provided me with all I needed in order to change. With German idealism, the situation was different. In my view Kant’s thought still blocks many people from treating the problems in nature as just as objective, just as real, as problems in human relations. Breaking out of anthropocentrism requires breaking out of Kantian idealism.

Correcting the mistakes of David Hume is far from easy, but it has been done for us, quite intentionally and successfully by Whitehead. Much of the strength of Personalism can be incorporated into a Whiteheadian system, but I do not think that a fully realistic view of the natural world can be incorporated into Personalism without fundamental philosophical changes.

As a problem of German Idealism’s understanding of nature, I have noted only its difficulty in responding well to the ecological crisis. But the problem is broader. Whitehead’s philosophy can be useful in science as well as in theology. Personalism can show how theology and science can coexist without conflict, but I do not see how it can assist science to develop. Quantum physicists do often find Whitehead useful. I think that Whitehead can also help us to understand the continuity and discontinuity between the animate and the inanimate as well as the whole process of emergence that we call evolution.

Most of what I have said above about the advantages of Whitehead is not particularly controversial. I will add that, also, specifically in the doctrine of God, I prefer Whitehead. I appreciate Personalism’s affirmation of God as personal, but I think the understanding of persons, when they are viewed in contrast to their natural contexts, is not adequate. Being personal then means too exclusively, like the minds or selves of human beings. Since Personalism does not have as clear a doctrine of “internal relations” as Whitehead, being like a human mind meant being primarily external to other minds. The relation to God is certainly I/thou rather than I/it, but the Pauline understanding of how God is in us and we are in God is hard to envision.

For Whitehead, every entity or event is to some extent inclusive of what has already occurred. Human beings include and reenact much more than do amoeba. God’s difference is the fullness of inclusion. Alongside God’s inclusion of us is the assurance that God is included in every experience. Whitehead’s God is a necessary participant in the coming to be of every creaturely event, but God is not the sufficient cause of any creaturely event. The occurrence of evil and injustice in the world is, of course, an enormous problem, but it is not an intellectual problem, and therefore not an inescapable existential problem. The fact that God works creatively in everything for good does not lead us to expect that everything will work well or that human beings will respond well to God’s gifts. God is included in us, but so are our personal past and indeed much, much else, that does not support God’s purposes.

Most Protestant theologians chose from the philosophical tradition Schleiermacher or Ritschl rather than Lotze, the leading Personalist. Some renewed Aristotle, who had remained important for Catholics. Many insisted that there was no need for philosophy, one could base one’s beliefs directly on the Bible.

In my opinion the choice by Christians of Personalism, and specifically of the Boston School of Personalism, was, in the second half of the nineteenth century and, down to World War II, an excellent choice, probably the best available. Personalism blended beautifully with the Social Gospel, which was the best available response to the social issues of the industrial era. Knowing that this combination was profoundly relevant to the intellectual and social problems of the time gave those who adopted it, including most Wesleyan leaders, a strength and assurance that we now sorely miss.

However, in a world in which German Idealism is no longer the leader in the philosophical world, and when the problems we face are all bound up with what is happening in the natural world, we cannot solve our problems by returning to that which worked so well in the recent past. I personally wish that the church would seek the same wholeness in the philosophy of Whitehead and the commitment to ecological civilization. It seems to have decided, instead, to largely abandon philosophical and theological commitments. I fear that this is a fatal mistake.

- John Cobb

Speeches & Lectures

by Martin Luther King, Jr