* * * * * * * * * *

Continuation of an 8-Part Series

Part 1 -

The Contours of a Post-Capitalistic, Whiteheadian-based,

Cosmopolitic Ecological Civilization and Society

R.E. Slater

August 10, 2020

Yes, a long title for an important subject which envisions a future world composed as an ecological society or civilization. Today's post will build on the last post, Capitalism & Economics - A Process-Based Ecological Society.

To begin, let's break down some terms:

Post-Capitalism - is a state in which the economic systems of the world can no longer be described as forms of capitalism. Various individuals and political ideologies have speculated on what would define such a world. According to some classical Marxist and some social evolutionary theories, post-capitalist societies may come about as a result of spontaneous evolution as capitalism becomes obsolete. Others propose models to intentionally replace capitalism. The most notable among them are socialism and anarchism. - Wikipedia

In my simple view, a post-capitalist world may simply be a more generous and equitable form of capitalism as different from state-capitalism, finanical capitalism, welfare capitalism and so forth as I previously had discuss in Part 3, What Can We Learn from America's Several Forms of Capitalism.

Whiteheadian-based economics and ecology was covered in Part 6, Rethinking Diversities and Varieties of Capitalism. It refers to Alfred North Whitehead's Philosophy of Organism, more commonly known as Process Philosophy. This philosophy is being applied to a wide variety of disciplines, including ecology, theology, education, cosmology, physics, biology, evolution, economics, and psychology, among other areas.

Process philosophy - also described as ontology of becoming, processism, or philosophy of organism - identifies metaphysical reality with change. In opposition to the classical model of change as illusory (as argued by Parmenides) or accidental (as argued by Aristotle), process philosophy regards change as the cornerstone of reality - the cornerstone of being thought of as becoming. - Wikipedia

Cosmopolitic is the joining of two groups into one [localized] community, that is, the living cosmos (e.g., creation, nature, the universe) with that of human habitation (located within the cosmos):

Cosmopolitanism (Wikipedia) - is the idea that all human beings are, or could, or should be, members of a single community. Different views of what constitutes this community may include a focus on moral standards, economic practices, political structures, and/or cultural forms. A person who adheres to the idea of cosmopolitanism in any of its forms is called a cosmopolitan or cosmopolite.

In a cosmopolitan community individuals from different places (e.g. nation-states) form relationships of mutual respect. As an example, Kwame Anthony Appiah suggests the possibility of a cosmopolitan community in which individuals from varying locations (physical, economic, etc.) enter relationships of mutual respect despite their differing beliefs (religious, political, etc.).

Various places are called "cosmopolitan"; this does not usually mean cosmopolitan; cosmopolitan means people of various ethnic, cultural and/or religious backgrounds live nearby and interact with each other.Etymology of the word cosmopolitan:

The word derives from the Ancient Greek: κοσμοπολίτης, or kosmopolitês, formed from "κόσμος", kosmos, i.e. "world", "universe", or "cosmos", and πολίτης, "politês", i.e. "citizen" or "[one] of a city". Contemporary usage defines the term as "citizen of the world".

Definitions of cosmopolitanism usually begin with the Greek etymology of "citizen of the world". However, as Appiah points out, "world" in the original sense meant "cosmos" or "universe," not earth or globe, as current use assumes. [Thus, "citizen of the cosmos."] One definition that handles this issue is given in a recent book on political globalization:

Cosmopolitanism can be defined as a global politics that, firstly, projects a sociality of common political engagement among all human beings across the globe, and, secondly, suggests that this sociality should be either ethically or organizationally privileged over other forms of sociality.

The Chinese term tianxia (all under Heaven), a metonym for empire, has also been re-interpreted in the modern age as a conception of cosmopolitanism, and was used by 1930s modernists as the title of a Shanghai-based, English-language journal of world arts and letters, T'ien Hsia Monthly. Multilingual modern Chinese writers such as Lin Yutang, Wen Yuan-ning also translated cosmopolitanism using the now more common term shijie zhuyi (ideology of world[liness]).

Examples by Reference - Cosmopolitanism, Cosmopolitics and Indigenous Peoples: Elements for a Possible Alliance

A Cosmopolitic of Ecological Civilization and Society is one which links ecology to causality itself, where cosmopolitics takes a much broader, metaphysical approach to ecological relations than is considered in the regular, scientific use of the term. The cosmos from this view is itself an ecology of interacting beings, ideas, practices, and technologies.

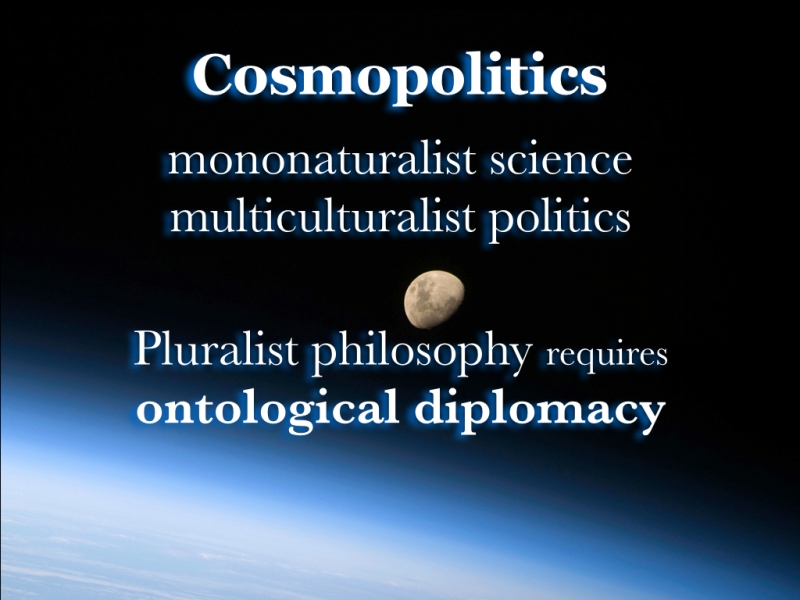

One last set of definition of Cosmopolitics:

Definition 1. The meaning of the simple phrase “cosmopolitics” seems almost self evident: Cosmopolitics refers to the politics of the cosmos. But this definition begs

further investigation—for what kind of “cosmos” has a “politics”? These two terms,

distinct in everday language, need to be brought together. But how?

Cosmos in this context designates the multitude of beings - human and nonhuman, living and nonliving - that together construct reality and form a collective society - a society that has always included the nonhuman despite frequent attempts to see things otherwise. Cosmos becomes attached to politics by means of the many associations continually forged and broken between humans and nonhumans. The cosmos in this sense is itself a historical being not juxtaposed to the history of human beings. - Cosmopolitics: An Ongoing Question, Paper delivered at The Center for Process Studies, Claremont, CA, Political Theory and Entanglement: Politics at the Overlap of Race, Class,Definition 2.

and Gender October 25, 2013, Adam Robbert and Sam Mickey

Particularly important for the Anthropocene is the challenge of representing the planet Earth in the political collective, specifically insofar as the planet is currently being shaped by human impacts. The planet cannot be excluded from the public lives of human beings, as it provides the basic conditions for those lives, and those lives are currently altering its basic systems of life, land, air, and water. The French anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour is an example of an advocate of cosmopolitics who is engaged in the task of facilitating the entrance of Earth into a political collective of humans and nonhumans.

SummaryFor Latour (2017), the complex assemblage of human-Earth relations is not simply Earth or a planet, for those designations connote a natural world unaltered by humans. In the Anthropocene, a designation that captures the entanglement of humans with Earth systems is Gaia. Latour is adapting this name from the Gaia hypothesis (also called Gaia theory), which was developed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, who used this name of an ancient Greek goddess of Earth to convey the complex, self-organizing dynamics of Earth systems. While contemporary scientists have expanded this theoretical model into the theories and methods of Earth systems science, the name Gaia is still significant as it indicates that Earth. - Cosmology and Ecology

A post-capitalistic, process-based cosmopolitic would take the entangled lives of all things, human or non-human, living and death (as death is also a process of life and vice-versa) to form an ecological society more in balance with the cosmos than it is now.

Moreover, it will be an ongoing process with no end to it for as soon as one thing is altered good or bad another process will occur whether good or bad. We, and the earth, have been living with these results for years.

Moreover, it will be an ongoing process with no end to it for as soon as one thing is altered good or bad another process will occur whether good or bad. We, and the earth, have been living with these results for years.

What this means is that we may set out to describe certain goals for America's economy which might include, among other elements the following set of initiatives:

What would the contours of a post-capitalist, process-based, ecological society look like?

- It would be socially just and equitable to all races, genders, sexes, ethnicities, and non-excluding faiths. Included in this will the occurrence of an earth justice in its various forms.

- It would value, and strive to create, multi-representational governance of the many and not the few in equitable and legal charity. This would also include the environment.

- It would lean America into an open-democratic and post-constitutional form of multi-plural governance to rebalance the excesses and corruption of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches as better checks on the powers that now exists in a dishonest and immoral Congress, unbalanced representation in the courts, and crass amassing of powers by the executive branch has shown under the Trumpian era of corruption and deceit.

- It would legally advocate for the oppressed and unequal with no voice as well as for nature which also has no legal voice pressed into serving the production of human materialism and amassing of wealth.

- It would move away from state capitalism and financial capitalism as America has now where power, wealth, and representation is concentrated in the hands of the few. But equally as well to strive to avoid becoming a welfare or socialist state so that those who are able may learn new skills and assist in the creation of an ecological society in every way possible.

- It would shun any form of authoritarian politic, ideology, religion, or governance where the voice of one does not speak for the voice of the other.

- It would lift up, and invest in, an economy that removes classes of wage labor slaves by rewarding workers with equitable profit-sharing plans, safe working environments, and self-fulfilling educational goals, studies, and apprenticeships.

- It would emphasis the value of multi-pluralism, multi-perspectivism, and multi-naturalism of speciation and biotic clime.

- It would value energy credits and debits in a non-currency based economy.

- It would solve global climate change by focusing on it one locality at a time.

- It would place existential value not in money or in material things but in relationships including that of nature and natural surroundings of mutual benefit.

- It would create generative, environmental-friendly, human and non-human biotic communities of thrival, goodness, and wellbeing.

- It would work towards rebuilding ruined biotic communities of land and water habitats (biomes) focusing on restoration, sustainability, and creative earthcare.

- Above all, it would integrate process philosophy into all of its religious and non-religious components, into process economies of ecological civilization, awareness, education, and avocation as a sufficient metaphysic of being and ontology of becoming until a better process might be identified more in sync with nature than what process philosophy has identified so completely and so very well.

The remainder of this post will be filled with helpful sources, references, articles and podcast discussions which will be continued further in another post: Matthew T. Segall - Cosmopolitic Ecological Civilizations with additional helpful resources.

Too, it may not be possible to complete this post or the next in a one-day read. In fact, this entire series is meant to give the reader a premier to the many sources speaking out to an Ecological Society. Please take your time examining all remaining areas.

As always my dear brothers and sisters,

Too, it may not be possible to complete this post or the next in a one-day read. In fact, this entire series is meant to give the reader a premier to the many sources speaking out to an Ecological Society. Please take your time examining all remaining areas.

As always my dear brothers and sisters,

Know the sovereign Lord reigns and is leading us all into a better state of redemption, and resurrection, than we have now. His love and wisdom is everlasting; His creation marvelous to behold; and His guidance enduring as we endure through pestilence, war, suffering, and death.

Peace,

R.E. Slater

August 11, 2020

August 11, 2020

* * * * * * * * * * *

Whitehead & Marx – A Cosmopolitico Approach

to Ecological Civilization

by Matthew T. Segall – EcoCiv Lecture

An Interview with Andrew Schwartz

Philosopher at the California Institute of Integral Studies

Teaching Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness

NOTES TO PODCAST BY R.E. SLATER

Spoken at the Fifth Annual Conference of the World Ecology Network

on the topic - Imagining and Materializing A Post-Capitalist World

~~ All book and authorial references are listed after the podcast ~~

Introduction

How do we bring Whitehead’s Process Philosophy of the metaphysic of cosmology together with Marx’s anthropocentric approach to Capitalism when imagining an ecological civilization beyond ourselves, our needs-and-wants to the needs-and-wants of others, to nature itself, and learning to act globally by acting locally?

First, why Alfred North Whitehead? As I see it, are a few of his contributions:

- Whitehead has provided the groundwork for a Constructive Postmodernism.

- Whiteheadian Process is Integrating all other disciplines such as: Process Science, Process Economics, Process Religion.

- Whitehead asked the deep metaphysical question of “What is the Structure of Reality?”

- Whiteheadian Process teaches the Relational Connectivity of the Universe to All Things, and All Things to Each Other.

- That the material world is not in motion for no reason or purpose.

- That no man or thing is an island to itself; that all things commune with each other.

- That Free, Rational Human Autonomy (sic, Reason or Consciousness) is insufficient in themselves.

- That Human Consciousness is not an anomaly but integral to the cosmogenic or evolutionary process of the universe.

So then, Why Karl Marx?

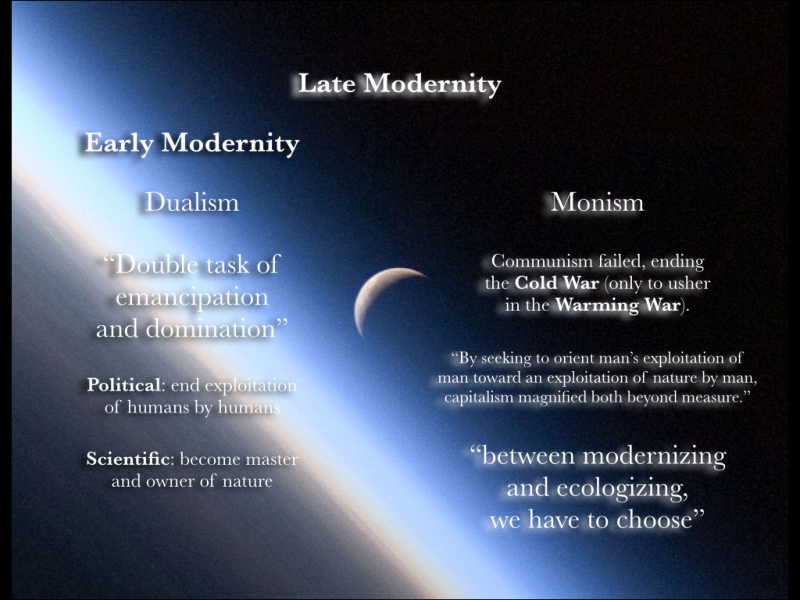

- Marx designed an industrialized human-centric perspective for the late 19th and early 20th century world.

- Marx provided a robust critique of capitalist relations and economics in the 19th century

- Marx was a revolutionary thinker and activist who stamped how political revolution unfolded throughout the world.

- The Fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1991 seemed to verify capitalism except that inequality kept rising along with ecological crises.

- Marx caused us to rethink human value in the economic, cultural, and environmental sense.

- Marx asked whether value is purely monetary?

- Marx asked whether labor for the sake of labor was sufficient in-and-of itself.

- Marx asked how we might extract value from human later and its end results?

- Marx asked whether value can be located in goods and services?

- Marx asked how do we might extract value from the natural world and whether this extraction was sufficient in-and-of itself.

Inferences to be Made

1 - Valueless Ecosystems Are Unseen and Destroyed

What are the ecological critiques of Marx which we may make through Whitehead’s Process of Organism (e.g., process philosophy) where the organism is the cosmos itself and all life within in?

Marx had wished to drive towards the financial equitability of the common laborer who might then enjoy the fruits of his labor. However, he overlooked the ecological impact of his pro-technology viewpoint.

As such, we have a thesis vs. anti-thesis problem between human freedom vs the mastery of nature as Marx steadily focused on the distribution of power into the hands of the laborer.

As a result, whether industrial technology was utilized in a capitalist or a communist economy each have created inequitably to the earth and are intrinsically destructive to the earth’s ecosystems.

2 - Valued Ecosystems Will Be Seen and Protected

When we bring Marx together with Whitehead we gain a perspective beyond the question of value to the human. We gain the perspective of asking the question of value to the non-human, to the environment, in which the human is but a part of - though mostly a destructive part of - to humanity's ignorance and short-sightedness. [Note: Indigenous peoples whom we considered ignorant savages actually "worshipped" or "cared" for the earth; who lived to its rhythms and tunes having become in-sync in their lives with the earth's perambulations - res]

Anyway, Whitehead understood the concept of "value" as being more than a human construct... more than what human beings could add to raw material (cf., John Locke spoke to man’s anthropocentrism in the manufacture of things akin to Marx).

Whitehead said, "Hey, wait a minute, human beings aren’t the only producers of value. Honeybees, ants, the slug, all labor. Each non-human entity is bringing value to nature's wonder." So then, "All species are value-creating creatures, and our human economy needs to incorporate non-human value into our lives and economy."

Whitehead's conclusion? If we’re not thinking of the natural world as a partner with us, but as a storehouse of raw materials we may plunder and harvest, then we will continue to direct environmental disruption into the earth until there is a total and complete destruction of the earth which in the Christian sense (as well as with many other religions) we are to nourish, care for, and help thrive in the generative sense.

Examples of Ecocivilizations Today?

China – is working towards a robust Ecological Civilization (EC) within a modified Marxist-based economy which is part State-Capitalism and part Communist (denial of human rights).

There exists a wealth of scholarship within China on EC but it cannot be easily obtained; too, the language barrier prevents its shared wealth of learning.

Why Consider a Post-Capitalistic Economy?

First of all, a post-capitalist economy DOES NOT EQUAL a communist or socialism economy. A post-capitalist economy does not wish to subjugate people’s freedom to shape their own destiny.

Example: China is moving rapidly towards ecology while exhibiting STATE-based capitalism coupled with free enterprise. But it is also moving against human rights; is actively creating a surveillance state; and generally, is internally acting as a communist form of government. Thus, it is not pure communism anymore but an amalgamation of capitalism with communism.

Marx disliked capitalism because its surplus value or dollars is stealing from the laborers forcing workers to become wage slaves without ownership of their own productivity or, in Whiteheadian terms, creative capacity, being forced to sell their labor at market prices to the owners of corporations who then used their captive-labor to resell that product while keeping the profit revenue for themselves. This makes capitalism and capitalistic economies a zero-sum game. Wages are kept low-enough, along with benefits and bonuses, so that owners might gain profit over the workers and the market.

Further, add to ownership wealth the gains of "Financial capitalism" and an even larger distortion occurs. Here, money is used as a commodity (a liquid product such as cash) to be invested to make more money so that the wage-ownership gap is heightened even more.

In a purely capitalistic economy (lets say, an Ayn Rand Type - see here and here), its purpose is to make money in-and-for itself, and as much of it as it can make, so that in relationship to both human workers and the ecosystems on which it depends, all are utilized as cheaply as possible.

As example, the purchase of land grants access to the environment's free raw materials while degrading both the environment and those who work for the industry with low working wages and unsafe environments. Both nature and worker are being used without putting back value into the value of the product which was extracted and produced.

This makes for an absurd capitalist system which makes money for money’s sake. What then arises are giant, state-centered corporate and politic authorities which place no value on human and natural entities, but do place value on the access to money and power each can obtain in usury of human and environmental resources.

Greed is not good. All profit must not go into private hands. Markets are not the problem. We want both power and wealth to be decentralized. To not grow or build giant monopolistic corporations, powerful State-based governances which are founded upon life consuming corporations.

Where Can Value Be Found?

In these types of state-run governments all politicians work for the giant corporations which hold sway over an economy. Our whole capitalist system is then set up to value making money for money's sake. That money alone is what gives value, and is justified by the fact that the more money made, they more jobs people will have. But let's ask the real question here... What jobs? Service jobs? Low paying jobs? Non-educating jobs? Self-consuming jobs? While all the while nature is ruined and destroyed?

Consequently, valuing capitalism in this way is to denigrate value in all other life-giving forces. We need a society where:

- power is radically democratized and de-centralized;

- where human beings are joined with nature as fully empowered members of society;

- where ethical standing is driven by higher consciousness and more intense forms of experience which create a value-hierarchy of membership (utilizing Whitehead)

- where every being has ethical standing including nature;

- where a post-capitalist world brings more social and economic equality;

- where a post-capitalist world brings in nature (or non-human beings) into an equitable relationship of compassion and preservation;

- where ethics and the sense of eco-community includes one another and nature itself;

- where nature is represented with legal rights (example, bumblebees, rivers, trees, etc.);

- that without human partnership with ecology we and it are all doomed in this Anthropocene age of usury and robbery.

We are all members of the same earth community where no one thing is more important then the other thing based upon a relativistic ethical scale of sentient life forms. Where we give legal rights to nature instead of just to corporations.

The Cosmopolitics of Post-Capitalism

Is success or value determined by pay? By what you own? By a nation's GDP? By political Power? By wealthy financial markets?

Why should corporation health be more valuable than individual health or environmental health?

Why is it that in a Corporation-Driven Capitalism as GDP goes up the quality of life goes down? That a corporation’s health is negatively averse to the wage labor market’s health as prices goes up and wages do not maintain pace?

It would be better that GDP had no correlation with human health but that isn’t the case. In fact, there is an inverse disconnection with human social contracts to rising GDP. Why? Because the priority of a corporate-capitalism is monetary wealth over human health.

Post-Capitalism says we can do better. The all wage earners may participate equally with owners and the wealthy who use owners. That value will be placed both on people and on the environment from where materials are produced.

What is Meant by a Cosmo-politic?

Let's think of politics in the sense of composing a common world. One which inhabits the same cosmos. The world is nature, and humans may use nature to its advantage of fulfilling needs and wants.

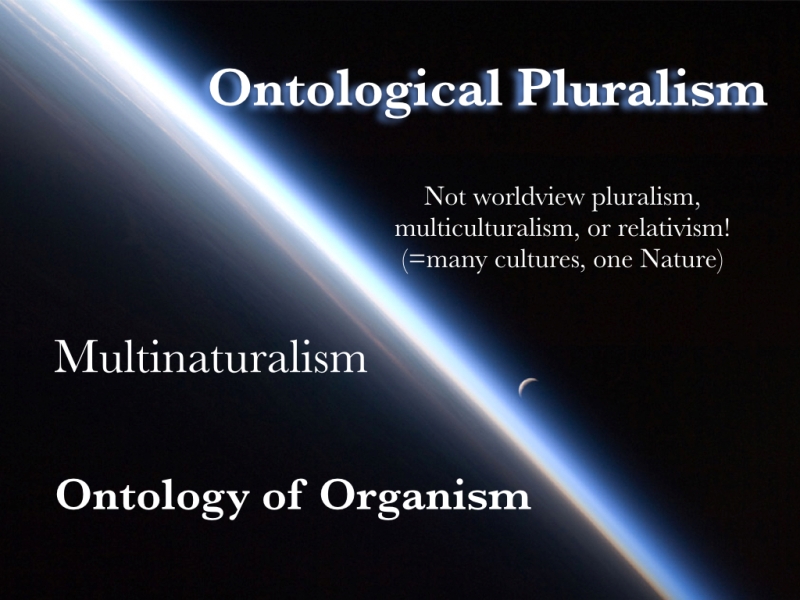

But this paradigm isn’t quite true. Nature itself is not unified. There exists many natures. Many biomes. Many environments within this one concept we call nature. There are land and sea biomes. There are forest and meadow biomes. There are garden and urban biomes. There are arctic and tropical biomes. There are salty and brackish biomes. There are northern pacific tidal pools and there are Great Barrier Reef biomes. Nature is not all one thing. Nature is composed of many, many biomes. Both large and great. Small and micro. When thinking of nature we must think of multi-natures or multi-naturalism.

Eco-Cosmopolitics Are Multi-Natural & Multi-Perspective

There is also the component of perspective. Humans living in each one of these biomes will have different perspectives about their biome. About their land or water habitat. We must then consider a multi-perspectival view of people living within their biome. Then bring with those perspectives their history, languages, nomadism, culture, trades, experiences, religion, education, and politics and those perspectives increase to a complex of perspectives. Lastly, add personal character, beliefs, personalities, psyches, along with the many identities of a community and its societies, and this multi-perspective is nearly infinite with ideas, awareness, self-identity, corporate-identity, imagination, and novelty for good and bad.

A Cosmo-politic must take in several facts:

- multi-naturalism

- multi-perspectivism

- multi-ethnicity and multi-culturalism

- multi-nationalism, mutli-locality

- multi-plural humanity

- multi-speciation of nature

- etc

We cannot assume a Process-Philosophy is so simple that it doesn't apprend change within change within change ad nauseum. It does, and it does it very well. This is why process philosophy can account for so many variables which will help build ecological societies centered on human and environmental value.

Therefore, a cosmopolitic must take in multi-naturalism (which is very different from multi-culturalism - itself supremely important). Meaning that there are many biotic spheres, climes, habitats, both micro and macro, across the world of nature. That nature is intensely complex. That it cannot be thought of as all one thing. That it is many things we might call one thing.

Eco-Politics cannot assume we, as humans, all live in the same context of nature, but that the nature around each civilization must account for its portion of habitat and locality. That each biome is connected with a group which subsists within that biome. That to live with nature must be to recognize the kind of nature surrounding us which we are living withing. There is no one unified natural world. We live in a multi-natural world.

Eco-Cosmopoitics Value Science

An eco-cosmopolitic values science. It allows itself to be critique throughout the never-ending process of theories becoming working, practical solutions. Disconnecting science from politics and religion will always be messy. Reducing the footprint of non-scientific or anti-scientific religious beliefs will allow science and intellectualism greater freedom to experiment, conjecture, and visualize what works and what doesn’t work.

Throughout science's history has been the recurring question, "What is it that makes humans human?" As science and technology challenge the boundaries between life and non-life, between organic and inorganic, this ancient question is more timely than ever.

Acclaimed object-oriented philosopher Timothy Morton invites us to consider this philosophical issue as an eminently political one. In our relationship with nonhumans, we will decide the fate of our own humanity.

Becoming human, claims Morton, actually means creating a network of kindness and solidarity with nonhuman beings, in the name of a broader understanding of reality that both includes and overcomes the notion of species.

Negotiating the politics of humanity is the first crucial step in reclaiming the upper spaces of ecological coexistence while resisting corporations like Monsanto and the technophilic billionaires who would rob us of our kinship with people and nonhumans beyond our species.

Multi-Species Democracy: Racism and Speciation Are A Lot Closer Than You Think

A cosmopolitic recognizes the:

- multi-plural nature of human society as well as the multi-speciation of nature;

- that we live in a pluri-verse rather than a uni-verse;

- that the universe itself is made up of multi-perspectives of itself.

In Whiteheadian terms, the universe is made up of actual occasions of experience which are the achievement of a perspective. That each actual occasion is a creative impulse achieving a new perspective on the universe whereby a new value is achieved with every new actual occasion. This is the process of concrescence where the many becoming one are being increased by one in an ongoing process of bubbling complexity and novelty where in each moment a new world is brought forth.

Cosmopolitics is the effort to compose some sense of commonality out of that multi-perspectival creative view of life. Cosmopolitics recognizes this and tells us politics is even harder than a simple black-and-white choice world. That it is filled with many perspectives, many needs, many wants.

Cosmopolitics gives to politics its own ontological weight in diplomacy where my world isn’t your world isn’t anybody else’s world, but we can still meet in some subliminal world of creativity. This is where we are to strive in negotiation and diplomacy. To find a common ground in which each may work with the other without denying fact, perspective, or value.

How do We Sum This All Up?

Reality is constituted by personal and corporate experiences which may help bridge over the divide between science and politics, facts and values. The world of experience may help bridge understanding between one another. Value experiences may come with different intensities into an ecological civilization and thereby direct its teleology (goal or purpose) in the achievement of generative beauty (Whitehead) or in the many celebratory themes of Thomas Merton’s writings on thrival and wellbeing.

We live in a world of celebration. One that is a multi-experiential, multi-perspectival. A world of both being and becoming. A world that is all about thriving in generative models of becoming. [This is the world God has made despite the agency He has given it to direct itself bearing His image. It is a world that is made for goodness. - res]

Though we value work. That work tells us we’re doing a good job or not, it must not be an end-value in itself. We should strive to enhance beauty. To make work more playful. The poet William Blake says that energy - work - is eternal delight. Creativity, novelty, imagination is within the bones of creation. It makes, builds, becomes. It cannot stop itself from becoming. This is the energy of the pluri-verse, or the cosmos.

Whitehead describes it as actual occasions of experience which translate back into our understanding of ourselves and society and cultural values which we are to enjoy in our existence. The Puritan Values of working because we must, or because God demands we be productive is unhelpful. Work is given as the byproduct of the energy we carry within us from the cosmos itself. It's called God's image. God's Self. God's own Being. We carry this light within us. This immense energy of wellbeing and thrival. And in the doing we may - we MUST! - experience its beauty and its enjoyment!

A post-capitalist politic is not simply making or valuing money. No it is far more than this. It speaks to one's quality of life, enjoyment of being, and relationships. Qualitative wellbeing and relationality is the new model. We must allow an existential transformation of ourselves, our religions, our secularity, our surrogate religions of consumerism, where we define ourselves by what we can buy or own or produced.

New iPhone, cars, houses, things, etc., do not define us. We must remove these materialistic things from ourselves, which create fear when they are not obtained. Yet these are value traps. They are pseudo-identity vacuums. We must rediscover ourselves in the cycles of the seasons; find re-creation in nature; in our relationships; to the stars and Milky Way above us; to trees, wildlife, and wild habitat. To find meaning beyond the thing itself to the thing it was made from. In nature. And in each other. To be willing to lose these value-surrogates by being reconnected with one another to the magic of the universe.

Ecological civilizations can be built on flourishing post-capitalistic societies which are to think globally by thinking locally; by acting locally. A global mindset of awareness is helpful but real change only happens at home. Meaning happens at home. Not our there where we don't live and interact with other beings and habitats.

Nothing Lasts Forever - Build A New Ethic!

As our old institutions crumble, our churches and religions will crumble too. We will conceive or ourselves and our religions differently. So too our modern ideas of civilization will be swallowed up as climate change rages with all its pandemics and other-worldly disasters of starvation, lack of drinking water, resource wars, and worse. Let us think ahead. Let us begin to build new civilizations of worth and value rather than want and need. To value each other as our greatest strengths and the lands we inhabit.

Did you know that when the great imperil power Rome fell the average peasant’s life expectancy, health, food, and wealth went up? Why? Because they weren’t giving away all their labor in taxation and theft to support the wealth of others.

As then as now. Things can become better - and certainly more local. The next future may be the future of locality. Of thinking about your place and your neighbor's place rathre than worrying about somebody's empire way out there beyond the borders of one’s community. Where what may look like collapse at the global level while only increase the need for our communities to be self-provisioning in their localities as they interact with one another and neighboring localities. In this cosmopolitic you are given permission to think and act locally.

End

- MTS (abridged, res)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

REFERENCES

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People

by Timothy Morton

August 22, 2017

An ecological reading of Marx (sans Whitehead)

A radical call for solidarity between humans and non-humans. What is it that makes humans human? As science and technology challenge the boundaries between life and non-life, between organic and inorganic, this ancient question is more timely than ever. Acclaimed object-oriented philosopher Timothy Morton invites us to consider this philosophical issue as eminently political. In our relationship with nonhumans, we decide the fate of our humanity. Becoming human, claims Morton, actually means creating a network of kindness and solidarity with nonhuman beings, in the name of a broader understanding of reality that both includes and overcomes the notion of species. Negotiating the politics of humanity is the first crucial step in reclaiming the upper scales of ecological coexistence and resisting corporations like Monsanto and the technophilic billionaires who would rob us of our kinship with people beyond our species.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Physics of the World-Soul: Whitehead's Adventure in Cosmology

by Matthew T. Segall

April 29, 2019

Whitehead was among the first initiates into the 20th century's new cosmological story. This book bring's Whitehead's philosophy of organism into conversation with several components of contemporary scientific cosmology-including relativistic, quantum, evolutionary, and complexity theories-in order to both exemplify the inadequacy of the traditional materialistic-mechanistic metaphysical interpretation of them, and to display the relevance of Whitehead's cosmological scheme to the transdisciplinary project of integrating these theories and their data with the presuppositions of human civilization. This data is nearly crying aloud for a cosmologically ensouled interpretation, one in which, for example, physics and chemistry are no longer considered to be descriptions of the meaningless motion of molecules to which biology is ultimately reducible, but rather themselves become studies of living organization at ecological scales other than the biological.

* * * * * * * * * * *

![What Is Ecological Civilization?: Crisis, Hope, and the Future of the Planet by [Philip Clayton, Wm. Andrew Schwartz]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51W+NzYOHUL.jpg) |

| Amazon Link |

What Is Ecological Civilization?

Crisis, Hope, and the Future of the Planet

September 8, 2019

The present trajectory of life on this planet is unsustainable, and the underlying causes of our environmental crisis are inseparable from our social and economic systems. The massive inequality between the rich and the poor is not separate from our systems of unlimited growth, the depletion of natural resources, the extinction of species, or global warming. As climate predictions continue to exceed projections, it is clear that hopelessness is rapidly becoming our worst enemy. What is needed—urgently—is a new vision for the flourishing of life on this planet, a vision the authors are calling an ecological civilization. Along the way they have learned that this term brings hope unlike any other. It reminds us that humans have gone through many civilizations in the past, and the end of a particular civilization does not necessarily mean the end of humanity, much less the end of all life on the planet. It is not hard for us to conceive of a society after the fall of modernity, in which humans live in an equitable and sustainable way with one another and the planet. This book explores the idea of ecological civilization by asking eight key questions about it and drawing answers from relational philosophies, the ecological sciences, systems thinking and network theory, and the world’s religious and spiritual traditions. It concludes that a genuinely ecological civilization is not a utopian ideal, but a practical way to live. To recognize this, and to begin to take steps to establish it, is the foundation for realistic hope.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Marx and Whitehead: Process, Dialectics, and the Critique of Capitalism

(SUNY series in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences)

by Anne Fairchild Pomeroy

January 29, 2004

Marx and Whitehead boldly asks us to reconsider capitalism, not merely as an "economic system" but as a fundamentally self-destructive mode that, by its very nature and operation, undermines the cohesive fabric of human existence. Author Anne Fairchild Pomeroy asserts that it is impossible to appreciate fully the impact of Marx's critique of capitalism without understanding the philosophical system that underlies it. Alfred North Whitehead's work is used to forge a systematic link between process philosophy and dialectical materialism via the category of production. Whitehead's process thought brings Marx's philosophical vision into sharper focus. This union provides the grounds for Pomeroy's claim that the heart of Marx's critique of capitalism is fundamentally ontological, and that therefore the necessary condition for genuine human flourishing lies in overcoming the capitalist form of social relations.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

For Our Common Home: Process-Relational Responses to Laudato Si'

by John B Cobb Jr (Author), Ignacio Castuera (Editor), Bill McKibben (Introduction)

August 25, 2015

In his papal letter Laudate si’ Pope Francis invited a worldwide dialogue on the interrelated issues of ecology, economy, and equity. This collection of essays, written from a process-relational perspective and representing multiple fields and faiths, answers that call and boldly aims to move the conversation forward.

On June 18, 2015, Pope Francis addressed the world about the fate of the planet, focusing especially on the threat of climate disaster. He called for a worldview that would emphasize the interconnectedness of things and what he called an "integral ecology."In Claremont, CA, earlier the same month, a conference called "Seizing an Alternative," keynoted by Bill McKibben, also focused attention on climate change and called for a new worldview that would reflect the interconnectedness of all things, or an "ecological civilization." The conference leaders saw that their aims and hopes now had a global leader. The goals of an integral ecology and an ecological civilization are the same. The task now for those who care about the fate of the world is to give whatever support they can to Pope Francis. As a first step, more than 60 persons involved in that conference answered the pope's call for dialogue and wrote responses to the pope's encyclical letter, Laudato si'. This book is a collection of those essays, written by people representing a diversity of faith traditions and cultures and many fields of activity and inquiry. They offer support, constructive criticism, and proposals for implementing the pope's ideas. To engage a larger public, it is important to engage the encyclical seriously, by widening and deepening the discussion. This book is offered in the hopes of facilitating that conversation.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Integral Ecology for a More Sustainable World:

Dialogues with Laudato Si' Illustrated Edition

by Dennis O'Hara (Editor), Matthew Eaton (Editor, Contributor), Michael T. Ross (Editor), Charles Camosy (Contributor), Guy Br. Consolmagno S.J. (Contributor), Anne Marie Dalton (Contributor), Timothy Harvie (Contributor), & 18 more

October 25, 2019

Laudato Si’ insists on a revolutionary human response to the public challenges of our time concerning the ecological crisis. The volume takes up the revolutionary spirit of Pope Francis and speaks to the economic, technological, political, educational, and religious changes needed to overcome the fragile relationships between humans and Earth. This volume identifies various systemic factors that have produced the anthropogenic ecological crisis that threatens the planet and uses the ethical vision of Laudato Si’ to promote practical responses that foster fundamental changes in humanity’s relationships with Earth and each other. The essays address not only the immediate behavioral changes needed in individual human lives, but also the deeper, societal changes required if human communities are to live sustainable lives within Earth’s integral ecology. Thus, this volume intentionally focuses on a plurality of cultural contexts and proposes solutions to problems encountered in a variety of global contexts. Accordingly, the contributors to this volume are scholars from a breadth of interdisciplinary and cultural backgrounds, each exploring an ethical theme from the encyclical and proposing systemic changes to address deeply entrenched injustices. Collectively, their essays examine the social, political, economic, gender, scientific, technological, educational, and spiritual challenges of our time as these relate to the ecological crisis.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Capitalism's Ecologies: Culture, Power, and Crisis in the 21st Century

by Jason W. Moore (Editor), Sharae Deckard (Editor),

Diana C. Gildea (Editor), Michael Niblett (Editor)

September 1, 2020

Ours is an era of planetary crisis. As scholars, activists, and citizens seek to make sense of our uncertain times, the limits of conventional environmental thinking have become clear. Rather than see “Society” and “Nature” as separate, Capitalism’s Ecologies illuminates how environmental and social change are intimately entwined. Contributors engage capitalism not as a social system independent of nature, but as a world-ecology of power, culture, and capital that flows through the web of life. In this rethinking, capitalism makes nature—and nature makes capitalism. Across successive essays, emergent and established scholars explore themes of colonialism, culture, race, gender, agriculture, literature, and waste to reveal capitalism’s varied organizations of humans and the rest of nature. Capitalism’s Ecologies asks readers to consider new ways of thinking about social and environmental crises, how they fit together, and what we might do about them.

* * * * * * * * * * *

| Amazon Link |

Cosmopolitics I (Post-Humanities)

by Isabelle Stengers (Author), Robert Bononno (Translator)

August 3, 2010

A sweeping critique of the role and authority of modern science in contemporary society, Isabelle Stengers’s sweeping work of philosophical inquiry builds on her previous intellectual accomplishments to explore the role of science in modern societies and to challenge its pretensions to objectivity, rationality, and truth. For Stengers, science is a constructive enterprise, a diverse, interdependent, and highly contingent system that does not simply discover preexisting truths but, through specific practices and processes, helps shape them.

---

From Einstein’s quest for a unified field theory to Stephen Hawking’s belief that we “would know the mind of God” through such a theory, contemporary science—and physics in particular—has claimed that it alone possesses absolute knowledge of the universe. In a sweeping work of philosophical inquiry, originally published in French in seven volumes, Isabelle Stengers builds on her previous intellectual accomplishments to explore the role and authority of science in modern societies and to challenge its pretensions to objectivity, rationality, and truth.

For Stengers, science is a constructive enterprise, a diverse, interdependent, and highly contingent system that does not simply discover preexisting truths but, through specific practices and processes, helps shape them. She addresses conceptual themes crucial for modern science, such as the formation of physical-mathematical intelligibility, from Galilean mechanics and the origin of dynamics to quantum theory, the question of biological reductionism, and the power relations at work in the social and behavioral sciences. Focusing on the polemical and creative aspects of such themes, she argues for an ecology of practices that takes into account how scientific knowledge evolves, the constraints and obligations such practices impose, and the impact they have on the sciences and beyond.

This perspective, which demands that competing practices and interests be taken seriously rather than merely (and often condescendingly) tolerated, poses a profound political and ethical challenge. In place of both absolutism and tolerance, she proposes a cosmopolitics—modeled on the ideal scientific method that considers all assumptions and facts as being open to question—that reintegrates the natural and the social, the modern and the archaic, the scientific and the irrational.

Cosmopolitics I includes the first three volumes of the original work. Cosmopolitics II will be published by the University of Minnesota Press in Spring 2011.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazn Link |

Cosmopolitics II, 3rd Ed. (Post-Humanities)

by Isabelle Stengers (Author)

A sweeping inquiry that critiques modern science’s claims of objectivity, rationality, and truth arguing for an “ecology of practices” in the sciences, Isabelle Stengers explores the discordant landscape of knowledge derived from modern science, seeking intellectual consistency among contradictory, confrontational, and mutually exclusive philosophical approaches. She concludes with a forceful critique of tolerance, proposing a “cosmopolitics” that rejects politics as a universal category and allows modern scientific practices to peacefully coexist with other forms of knowledge.

- blurb source - https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/cosmopolitics-ii

---

Originally published in French in seven volumes, Cosmopolitics investigates the role and authority of the sciences in modern societies and challenges their claims to objectivity, rationality, and truth. Cosmopolitics II includes the first English-language translations of the last four books: Quantum Mechanics: The End of the Dream, In the Name of the Arrow of Time: Prigogine’s Challenge, Life and Artifice: The Faces of Emergence, and The Curse of Tolerance.

Arguing for an “ecology of practices” in the sciences, Isabelle Stengers explores the discordant landscape of knowledge derived from modern science, seeking intellectual consistency among contradictory, confrontational, and mutually exclusive philosophical ambitions and approaches. For Stengers, science is a constructive enterprise, a diverse, interdependent, and highly contingent system that does not simply discover preexisting truths but, through specific practices and processes, helps shape them.

Stengers concludes this philosophical inquiry with a forceful critique of tolerance; it is a fundamentally condescending attitude, she contends, that prevents those worldviews that challenge dominant explanatory systems from being taken seriously. Instead of tolerance, she proposes a “cosmopolitics” that rejects politics as a universal category and allows modern scientific practices to peacefully coexist with other forms of knowledge.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Thinking with Whitehead:

A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts

by Isabelle Stengers (Author), Michael Chase (Translator), Bruno Latour (Foreword)

September 1, 2014

Alfred North Whitehead has never gone out of print, but for a time he was decidedly out of fashion in the English-speaking world. In a splendid work that serves as both introduction and erudite commentary, Isabelle Stengers―one of today’s leading philosophers of science―goes straight to the beating heart of Whitehead’s thought. The product of thirty years’ engagement with the mathematician-philosopher’s entire canon, this volume establishes Whitehead as a daring thinker on par with Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Michel Foucault.

Reading the texts in broadly chronological order while highlighting major works, Stengers deftly unpacks Whitehead’s often complicated language, explaining the seismic shifts in his thinking and showing how he called into question all that philosophers had considered settled after Descartes and Kant. She demonstrates that the implications of Whitehead’s philosophical theories and specialized knowledge of the various sciences come yoked with his innovative, revisionist take on God. Whitehead’s God exists within a specific epistemological realm created by a radically complex and often highly mathematical language.

“To think with Whitehead today,” Stengers writes, “means to sign on in advance to an adventure that will leave none of the terms we normally use as they were.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Staying with the Trouble:

Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Experimental Futures)

by Donna J. Haraway

September 19, 2016

In the midst of spiraling ecological devastation, multispecies feminist theorist Donna J. Haraway offers provocative new ways to reconfigure our relations to the earth and all its inhabitants. She eschews referring to our current epoch as the Anthropocene, preferring to conceptualize it as what she calls the Chthulucene, as it more aptly and fully describes our epoch as one in which the human and nonhuman are inextricably linked in tentacular practices. The Chthulucene, Haraway explains, requires sym-poiesis, or making-with, rather than auto-poiesis, or self-making. Learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying together on a damaged earth will prove more conducive to the kind of thinking that would provide the means to building more livable futures. Theoretically and methodologically driven by the signifier SF—string figures, science fact, science fiction, speculative feminism, speculative fabulation, so far—Staying with the Trouble further cements Haraway's reputation as one of the most daring and original thinkers of our time.

* * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Amazon Link |

Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime,

1st Edition

by Bruno Latour

The present ecological mutation has organized the whole political landscape for the last thirty years. This could explain the deadly cocktail of exploding inequalities, massive deregulation, and conversion of the dream of globalization into a nightmare for most people.

What holds these three phenomena together is the conviction, shared by some powerful people, that the ecological threat is real and that the only way for them to survive is to abandon any pretense at sharing a common future with the rest of the world. Hence their flight offshore and their massive investment in climate change denial.

The Left has been slow to turn its attention to this new situation. It is still organized along an axis that goes from investment in local values to the hope of globalization and just at the time when, everywhere, people dissatisfied with the ideal of modernity are turning back to the protection of national or even ethnic borders.

This is why it is urgent to shift sideways and to define politics as what leads toward the Earth and not toward the global or the national. Belonging to a territory is the phenomenon most in need of rethinking and careful redescription; learning new ways to inhabit the Earth is our biggest challenge. Bringing us down to earth is the task of politics today.

![Humankind: Solidarity with Non-Human People by [Timothy Morton]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51v8dOdn-SL.jpg)