Evangelicalism Is Dead!

Long Live Evangelicalism!

by Roger Olson

March 19, 2013

Link to - The Future of Evangelicalism, Part 1

Link to - The Future of Evangelicalism, Part 2

Link to - The Future of Evangelicalism, Part 1

Link to - The Future of Evangelicalism, Part 2

Here is the first part of my talk at George Fox Evangelical Seminary (March 11, 2013). The second part will come next (in a day or two). (I posted both talks a week ago, but the formatting made it virtually unreadable for most people.)

The Future of Evangelicalism, Part I

A Lecture by Roger E. Olson

given at

George Fox Seminary

March 11, 2013

Part 1: The Demise of the Evangelical Movement

and the Survival of the Evangelical Ethos

Part 1: The Demise of the Evangelical Movement

and the Survival of the Evangelical Ethos

I’ve been asked to talk about the future of evangelicalism. I’m always hesitant to predict the future. Predictions are often taken as prophecies and we all know what the prescription is for false prophets. Please don’t take anything I say here today as prophecy. I have some thoughts about where evangelicalism is going, but they are only educated guesses and don’t even rise to the level of predictions. Much of what I will say, however, has to do with evangelicalism’s present and past. Some of it will be descriptive and some of it will be prescriptive—the difference between “is” and “ought.”

Allow me to begin with some personal reflections. Who am I to talk about evangelicalism? I grew up in the thick of it—whatever “it” is, exactly. I knew we were evangelicals by the time I was in high school if not before. We were also Pentecostals, but we were Pentecostals who played well with non-Pentecostals evangelicals. My uncle was president of our tiny Pentecostal denomination. My father and several aunts and uncles were ministers and missionaries. My maternal grandparents were Evangelical Free, so my mother was raised in that denomination. Much to their chagrin, she become Pentecostal and then married my dad who was pastoring a small Pentecostal mission in the slums of Des Moines. Some of my mother’s siblings were Evangelical Covenant. My paternal grandparents were Church of God (Anderson, Indiana), but late in life my grandmother became Pentecostal. My father followed her into that. So I have deep family roots in evangelicalism. When I was growing up we, my family, commonly divided the whole Christian world into two groups—evangelicals and “nominal Christians.” My father participated in the local evangelical ministers groups in cities where he pastored. My uncle served on the national board of the National Association of Evangelicals. Billy Graham was one of our heroes—along with Oral Roberts.

During high school I became deeply involved in Youth for Christ. My future wife’s father was the city director of YFC and she sang in its “Youth Chorale.” I led our high school’s “Campus Life” club, a ministry of YFC, and helped organize city wide YFC rallies. It was through YFC that I really first became aware of something called “evangelicalism” - a transdenominational movement and alliance of believers in Jesus Christ who shared a relatively conservative theology and believed in conversion and evangelism. We actively proselytized our nominally Christian schoolmates. In YFC I came into direct contact with Baptists, Evangelical Free, Nazarenes, Wesleyans, Free Methodists, Christian Reformed and many other Christians who shared a common spiritual and theological ethos and gradually became aware of a movement called evangelicalism that transcended my own denomination and even Pentecostalism.

|

| Donald Grey Barnhouse |

While I was attending our Pentecostal Bible college I began to read Eternity magazine—an evangelical publication of the non-profit Evangelical Foundation founded by Donald Grey Barnhouse, pastor of Tenth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia and radio preacher and author of numerous Bible commentaries. Through Eternity I became further aware of evangelicalism through articles written by people like Donald Bloesch, Bernard Ramm, James Montgomery Boice and many other evangelical authors. I began to read especially Bloesch’s books, many of which had to do with evangelicalism as a movement. One was The Evangelical Renaissance which served as my first scholarly introduction to evangelical faith and spirituality. Then I began to read Christianity Today and then InterVarsity’s magazine His. I began to read Francis Schaeffer’s books which greatly influenced me early in my evangelical student career.

|

| James Montgomery Boice |

After Bible college I attended North American Baptist Seminary in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It’s now Sioux Falls Seminary and was then and still is a mainline evangelical seminary not limited to Baptists. One of my professors was James Montgomery Boice, publisher of Eternity and pastor of Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia after Barnhouse. I was absolutely in awe of him. (He taught one course at the seminary while on a sabbatical from his pulpit.) While in seminary I continued to read Eternity and Christianity Today and my first published piece was a book review in Eternity. All my professors were evangelicals. I took three graduate theology courses at a local Lutheran college that hosted an extension of Luther Seminary. I couldn’t help but notice the difference between the evangelicalism of NABS and those professors.

While in seminary I served as assistant pastor at a local Pentecostal-charismatic-evangelical church and attended the city’s evangelical ministers’ alliance meetings. I served on the organizing committee for two Billy Graham associate evangelists’ crusades—John Wesley White’s and Leighton Ford’s. Eventually I came to view evangelicalism as my larger Christian “home” beyond my own denomination and church. By the end of seminary I no longer considered myself Pentecostal; I was evangelical first and Baptist second. In order to understand evangelicalism I read voraciously books about the evangelical movement including ones by George Marsden, the dean of evangelical historians before Mark Noll.

All that is to say, in brief, that “evangelicalism” has always been part of my identity and became more important to me than ever once I shed my Pentecostal identity. Yes, I became Baptist, but being evangelical was more important to me than that. I could move easily among non-Baptist evangelicals and often did. Organizations like InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Christian Scholar’s Review (which I edited for five years), the Christian College Coalition (now renamed the Coalition of Christian Colleges and Universities), the Evangelical Theological Group of the American Academy of Religion, the National Association of Evangelicals, Christianity Today, Inc., the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, all became spaces in which I felt at home and moved around easily. Eventually I began to write about evangelicalism. Probably the high point of my scholarly contribution to the subject came in 2004 when Westminster John Knox Press published my book The Westminster Handbook to Evangelical Theology that included a very lengthy essay on “The Story of Evangelical Theology.” Around the same time I found myself included, with a brief biography, in the Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism written by Randall Balmer and published first by Westminster and then by Baylor University Press.

All that is to say that I have some credentials, some “street-cred,” to talk about evangelicalism even if I am no George Marsden or Mark Noll.

Let me begin, then, with a statement about the present status of evangelicalism and then go backwards and then forwards. It is my considered opinion that the evangelical movement no longer exists. As a cohesive movement, it has dissolved. Of course, it never was perfectly cohesive, but throughout much of the 1950s and into the 1970s it was relatively unified—not as a bounded set category, which no movement really is, but as a centered set category. The movement had a gravitationally strong center that held it together. In my opinion, that gravitational center has lost its strength and the movement has dissolved. What was once a relatively united movement has become little more than a memory. Some of us miss it. What’s left is what was there before the movement—an “evangelical ethos.” And also left is a memory of affinity, fellowship, common cause, cooperation and united action across denominational lines.

|

| The Frist Great Awakening |

So what happened and what does the future hold?

As a distinct movement, evangelicalism was born in 1942 in St. Louis. That was when and where the National Association of Evangelicals was founded. Of course, it had a pre-history going back to the Great Awakenings of the 1740s and early 1800s. In a very real sense Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley, both born in 1703, were the two founders of modern evangelical Christianity. I’m not talking now about the movement but the ethos. One thing I insist on is this distinction between evangelicalism as an ethos and evangelicalism as a movement. Of course they’re related; the movement is a visible, somewhat organized expression of the ethos. But the ethos pre-dates the movement and outlasts it. The ethos was born out of the pietism and revivalism of the Great Awakenings. Yes, of course, even that had a pre-history, but we won’t keep backing up.

So what is the evangelical ethos that emerged out of the Great Awakenings—first and second? Noll and David Bebbington have identified it with four hallmarks: biblicism, conversionism, crucicentrism, and activism. I have suggested a fifth—respect for the Great Tradition of Protestant orthodoxy, broadly defined in terms of Christology and soteriology—Jesus as God, the cross as vicarious atonement, and salvation by grace alone through faith. The Great Awakenings added to Protestant orthodoxy an experiential dimension called “conversional piety”—the born again experience, an emphasis on regeneration, and focus on a “personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” Crucicentrism is the centrality of the cross in evangelical preaching and worship. Biblicism is a special regard for the Bible as God’s inspired, infallible word but also love for the Bible as the story of God’s saving history for us and with us—a message meant directly for the individual’s heart and life and not only for the church. Activism is the evangelism impulse and the desire to change the world that inspired the great world evangelism crusades that grew out of especially the Second Great Awakening.

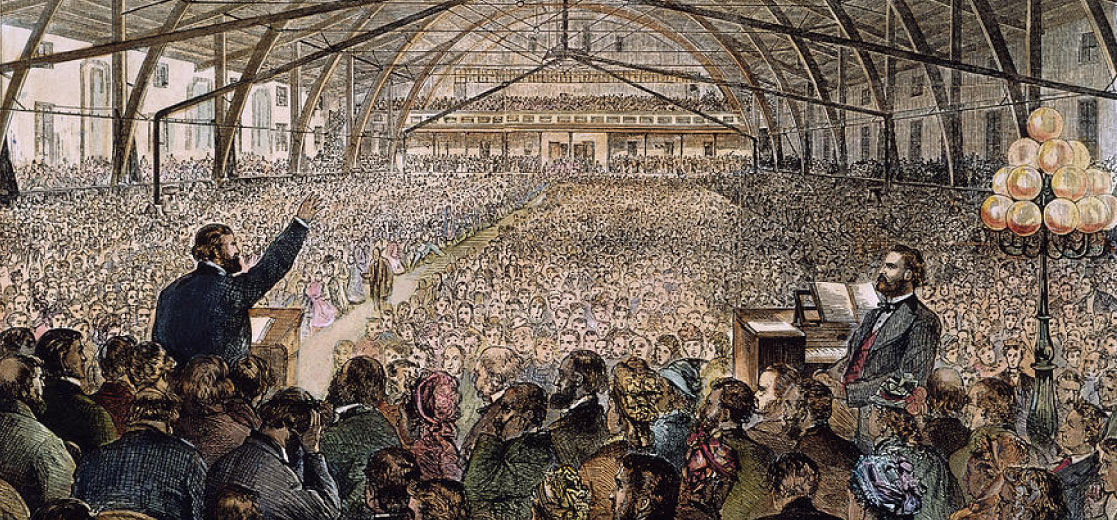

|

| The Second Great Awakening |

The evangelical ethos, then, was Protestant Christianity on fire, energized with passion and zeal, Jesus Christ experienced as living Lord and Savior, the gospel as transforming power. But it lacked a coherent theological framework until that was provided by the Princeton School of Theology formulated by Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, and Benjamin Warfield. Not all evangelicals were thrilled with their Reformed spin on Protestant theology and evangelicalism, however, so alongside them arose lesser known theologies by Methodists such as John Miley and Baptists such as Augustus Hopkins Strong. Add into that mix the revivals of D. L. Moody and the strong premillennialism of the Plymouth Brethren and the Holiness-healing movements and the Keswick spirituality and by 1901 the evangelical ethos was spreading quickly through a large number of somewhat diverse theological expressions.

Then came the fundamentalist movement, a militant evangelical opposition to the growing liberal movement in mainline Protestant denominations. Evangelical leaders such as Baptists William Bell Riley and J. Frank Norris hardened evangelicalism into an exclusive club and angry mob that divided denominations with northern Baptists and Presbyterians especially fracturing into numerous small denominations. After 1925 and the infamous Scopes “Monkey Trial” fundamentalism went underground, so to speak, quietly building its own separate culture of Bible colleges, publishing houses, evangelistic organizations and missions agencies. During the 1920s and 1930s American fundamentalism was the chief organized embodiment of the evangelical ethos, even though that ethos continued to have other expressions in, for example, Pentecostalism and the Holiness churches. But, by-and-large, it found expression mainly in anti-intellectual, Christ-against-culture organizations that wiped their hands of responsibility for society at large and waited for Christ to return to rescue them from the world going to hell in a hand basket.

During the early 1940s fundamentalist organizer Harold John Ockenga and some New England friends began to dream of a new organized expression of the evangelical ethos—one that would shed fundamentalism and emerge into the light of day with a renewed cultural presence that would be just as biblical and conversionist but less anti-intellectual and separatistic. That dream came true in 1942 with the founding the NAE. Fundamentalists declined to join it, probably to the secret delight of Ockenga and his friends. Of course, they were fundamentalists to liberal Protestants like Harry Emerson Fosdick and the Federal Council of Churches (which later changed its name to the National Council of Churches). But fundamentalists labeled them “neo-evangelicals” and liberals labeled them “neo-fundamentalists.” Eventually, they won the right to be known simply as “evangelicals.” Their champion became Billy Graham who virtually defined the post-fundamentalist evangelical movement—an alliance of denominationally diverse, relatively conservative, revivalistic Protestants who wanted to be culturally engaged, socially progressive (at least up to a point), and intellectually respectable.

|

| Evangelist Billy Graham addressing the congregation in Trafalgar Square in London. Fred Ramage / Getty Images |

Billy Graham 1957

The rest of the story is well known, often told by scholars such as Marsden, Noll, Joel Carpenter, Randall Balmer and, more recently, Kenneth Collins and yours truly. The heyday of the new evangelical movement symbolized by Billy Graham and his widespread ministries, Christianity Today, the NAE, Eternity, World Vision, the Christian College Coalition, Youth for Christ, InterVarsity, etc., was the 1950s. In spite of very real and significant theological differences, the evangelical coalition and movement forged ahead, steadily gaining ground against its main competitors, separatistic fundamentalism and modernistic liberalism. The secular news media began to pay special attention to it, as a movement with a distinct ethos, when Jimmy Carter ran for president in the late 1970s. Carter, of course, identified with the movement and proudly labeled himself an evangelical. If there had ever been an evangelical president before Carter, it was difficult to tell. None had so openly identified with that ethos of “born again Christianity.” Time magazine labeled 1976 the “Year of the Evangelicals,” announcing that 34% of all Americans claimed to have had a “born again experience.”

Right about then, however, the movement, at its peak of popularity, was beginning to dissolve. Remember, I’m not talking about the evangelical ethos but the movement. Fortunately, I’m glad to say, the ethos is alive and well, but the movement began to die in the late 1970s—just when the media was taking notice and touting it as a powerful socially transformative force.

Marsden, the dean of evangelical historians, wrote in his book 1990 book Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism that as of 1967 evangelicalism was no longer a cohesive movement. According to Marsden, “By 1967…it was becoming impossible to regard American evangelicalism as a single coalition with a more or less unified and recognized leadership.” (p. 74) Marsden attributes this dissolving of the movement to an internal crisis. He cites as a critical turning point Christianity Today’s 1968 replacing of Carl Henry as chief editor (Henry was its founding editor) with Harold Lindsell. This signaled a shift toward neo-fundamentalism at the core of evangelicalism. Many evangelicals reacted against Lindsell’s hard core conservatism—both political and theological. Oregon Senator Mark Hatfield and the “Sojourners” group hoisted a left-leaning evangelical banner and Fuller Seminary drifted in that direction theologically.

I tend to date the demise of evangelicalism later than Marsden. I was high school when those things happened. While in college and seminary in the 1970s I witnessed them. I read The Post-American, the original title of the magazine that later became Sojourners, avidly. I paid attention when Lindsell published The Battle for the Bible in 1976 and Carl Henry left the magazine as a regular columnist. The moderate-to-left-leaning evangelical seminary I attended suddenly jerked to the right as constituents, alarmed by The Battle for the Bible, imposed an inerrancy statement on it. The faculty had to sign it to keep their jobs. One, New Testament professor Lee MacDonald, refused and resigned. Then came the founding of the “Moral Majority” and Jerry Falwell’s emergence as an evangelical leader and spokesman. Falwell had previously been a separatistic fundamentalist who, during the 1960s, heaped scorn on the “neo-evangelicals” as compromisers of the pure faith.

As I said, in my opinion, it was really during the few years immediately following publication of The Battle for the Bible that the evangelical movement dissolved. Those years also corresponded with the gradual retirement of the movement’s main prototype and champion, its figurehead leader, Billy Graham. As long as Graham was active, the movement stayed together, relatively united, largely by his personality and huge empire of ministries. The breaking up of the movement should have come as no surprise. Marsden and other evangelical historians had been warning of it for some time. The reason it was predictable is that post-World War 2, post-fundamentalist evangelicalism always was an unstable compound.

When the National Association of Evangelicals formed in 1942, and as relatively conservative Protestants rallied together around the banner of Billy Graham throughout the 1950s, there was a tendency to paper over one very significant rift between two groups of evangelicals. One group found its theological and spiritual roots in the Reformed tradition especially as that was handed down to them via the Old Princeton School of theologians of the 19th century—Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, A. A. Hodge, and Benjamin Warfield. Their twentieth century successor and representative J. Gresham Machen left Princeton Seminary and the Northern Presbyterian denomination to found the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and Westminster Theological Seminary. This branch of evangelicalism tended to be Calvinistic and to regard correct doctrine as the enduring essence of evangelical faith. It held high the doctrines of biblical inerrancy, the absolute sovereignty of God and justification by faith alone.

The other branch of neo-evangelicalism was rooted in revivalism including the Holiness-Pentecostal movements, the Keswick movement and pietism generally. The emphasis of this branch was not as much doctrine as spirituality—a spirituality Stan Grenz and I have labeled “convertive piety” or “conversional piety.” This branch held high regeneration and sanctificiation, often free will, and a view of Scripture’s inspiration not tied to inerrancy.

How could two such profoundly different Christian traditions combine to form one movement called “evangelicalism?” I believe one answer to that lies in the Baptist ingredient. By 1942 Baptists formed a large portion of American fundamentalists and many of them were dissatisfied with the separatistic and anti-intellectual drift of fundamentalism. That dissatisfaction was illustrated by the separation between the General Association of Regular Baptist Churches and the Conservative Baptist Association with the former finding Billy Graham dangerously liberal and the latter embracing Graham. The Conservative Baptists, together with other moderate Baptist groups, often held together the two traditions—what evangelical historian Donald Dayton has called the Pietist-Pentecostal paradigm of evangelicalism and the Puritan-Presbyterian paradigm of evangelicalism. The former emphasized experience as the sine qua non of authentic evangelical faith while the latter emphasized correct doctrine as that.

This tendency of moderate Baptists, neither fundamentalist nor liberal, to include both paradigms itself became the paradigm for neo-evangelicalism. In essence, Ockanga and Henry and other founders of the movement were saying “Let’s paper over this gulf and form a coalition of moderately conservative Protestants who are neither fundamentalist nor liberal.” To the right of the NAE was fundamentalist Carl McIntire’s American Council of Christian Churches that would not have fellowship with Pentecostals or “mainliners.” To the left was the Federal Council of Churches, later re-named the National Council of Churches. Within the NAE and the neo-evangelical movement was everything from the Church of the Nazarene to the Christian Reformed Church—a motley crew of Protestants who had little in common other than being neither fundamentalist nor liberal.

Gradually, throughout the late 1970s, these two branches of evangelicalism pulled further apart over issues such as inerrancy, political involvement, predestination, the attributes of God, gender roles in family and church, and the possible salvation of the unevangelized. By the first decade of the 21st century the two sides were barely speaking to each other. Each side had its champions—D. A. Carson and John Piper on one side and Stan Grenz and Clark Pinnock on the other. Many evangelicals tried to mediate the divorce and bring evangelicals back together with limited, and I would say ultimately no, success. Richard Mouw, president of Fuller Theological Seminary, himself a moderate-to-progressive evangelicals, has worked tirelessly to hold together a broad evangelical consensus and coalition. With him are Timothy George and Christianity Today. In 2008 Mouw, George, David Neff of CT and a number of like-minded moderate evangelicals published “An Evangelical Manifesto” that called for evangelical unity and renewal. It did not mention biblical inerrancy, women’s ordination, or most controversial issues that have divided evangelicals.

At the same time, however, Carson and his conservative evangelical colleagues, all Reformed theologically, created “The Gospel Coalition” and held meetings and published books calling for renewed evangelical commitment to doctrines such as inerrancy, monergistic salvation, penal substitutionary atonement, and male headship.

Now, a new group of left-leaning evangelicals calling itself “Missio Alliance” will hold its first annual gathering in suburban Washington, D.C. in April, 2013. Present and speaking will be many self-identified evangelicals associated with the emerging church movement, anathema to Carson and the Gospel Coalition and a cause of concern to Mouw and George and their group. Emerging as a spokesman for this group is Scott McKnight, but in the background are recently deceased postconservative evangelical Stanley Grenz and (still living) British scholar N. T. Wright.

It is my considered opinion that “the” evangelical movement, “the” post-fundamentalist, neo-evangelical movement that flourished in the 1950s and 1960s and was, in my opinion, still alive if not well in the 1970s has died. It has fractured into at least three separate groups that have little contact with each other and often stand toward each other with postures of opposition and even competition. First, there are what I call the conservative, neo-fundamentalist evangelicals. They are represented by the Gospel Coalition and similar organizations such as the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals that publishes Modern Reformation. Second, there are what I call the conservative, mediating evangelicals. They are represented by Mouw, George, Neff and Christianity Today. Finally, there are what I call the postconservative evangelicals. They are represented by McKnight and the Missio Alliance and magazines such as Sojourners and Relevant. These are not monolithic groups; each has much diversity within it. But they are, as evangelicalism once was, relatively cohesive affinity groups, alliances, coalitions.

So why do I call them all, and many more, “evangelicals?” It’s because I do not consider “evangelical” a concept tied to the post-WW2, post-fundamentalist, neo-evangelical movement. “Evangelical” is an ethos, not just a movement. Movements come and go, ethoses that gave them their identities and outlived them live on. Let’s look at some examples of this outside of our present subject.

“New Thought” was a spiritual-philosophical-quasi-religious movement that flourished in America in the 19th century. It emphasized mind-over-matter with physical healing and financial prosperity possible through positive thinking and speaking. Its practitioners shared an ethos and on that basis they formed a movement that transcended their own individual practices and organizations. The International New Thought Alliance was founded in 1915 to coordinate practitioners’ efforts and creating a better world and to provide fellowship among them in spite of certain sometimes profound differences. The fundamentalists of New Thought, Mary Baker Eddy’s Church of Christ, Scientist (“Christian Science”) refused to join even though everyone knows it was inspired by New Thought philosophy. For much of the later 19th and early 20th centuries the Unity School of Christianity founded by Charles and Myrtle Fillmore was the best known of the New Thought organizations. It still has churches all over North America. Even though the International New Thought Alliance still exists, the once flourishing and influential New Thought movement exists no more. At best it’s an affinity group with many New Thought practitioners and teachers existing and operating quite apart from any explicitly New Thought organization. New Thought gradually filtered out of its movement into the fabric of American culture. Protestant ministers such as Norman Vincent Peale and Robert Schuller and now Joel Osteen have re-packaged and popularized it for non-New Thought Christians. Some would say they have vulgarized it.

What New Thought really was and is is an ethos. The ethos pre-dates Mary Baker Eddy and the Fillmores and the New Thought Alliance. And it is still very much alive and well, taking on new forms and finding new expressions all the time. The Pentecostal-charismatic “prosperity gospel” is one of them. The New Thought ethos was probably born out of American pragmatism, the popularity of esoteric ideas and practices such as Mesmerism, and mind healer Phineas Quimby’s peripatetic therapeutic ministry. Lurking somewhere in the background of New Thought is almost certainly German philosophical idealism, transported onto American soil and translated for always optimistic American individualists. Today it is ubiquitous and nearly identical with “the American ‘can-do’ spirit.”

I could give many examples of the distinction between “ethos” and “movement.” The charismatic movement arose in the 1960s and died sometime later. But its pre-existence was in Pentecostalism and its post-existence is in “renewalism,” Third Wave Christianity and television evangelism.

The evangelical movement of my youth is dead. It broke apart. Relics such as Christianity Today and the rather ineffectual NAE remain. What’s left? The evangelical ethos—that pre-dated the movement, was given new expression by the movement, and is still shared in distinct expressions by the three evangelical groups I mentioned above.

So what is this evangelical ethos? Each group of evangelicals will give it a somewhat different description. One evangelical party will emphasize its experiential dimension—“conversional piety.” Another one will emphasize its doctrinal dimension—usually then with emphasis on a distinctive view of Scripture that includes inerrancy. Yet another one will emphasize its culture-transforming dimension with stress on changed people changing culture toward the Kingdom of God.

|

| Rachael Held Evans |

- Roger Olson

*David Bebbington: Bebbington’s Quadralateral

Bebbington is widely known for his definition of evangelicalism, referred to as the "Bebbington quadrilateral”, which was first provided in his 1989 classic study Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s.

Bebbington identifies four main qualities which are to be used in defining evangelical convictions and attitudes:

- biblicism - a particular regard for the Bible (all essential spiritual truth is to be found in its pages)

- crucicentrism - a focus on the atoning work of Christ on the cross (Jesus died for sinners)

- conversionism - the belief that human beings need to be converted (born-again)

- activism - that the gospel needs to be expressed in words and actions