Objective Immortality and Subjective Immortality

by Jay McDaniel

Process philosophy offers two views of the possibility of life after death, typically called objective immortality and subjective immortality.

In objective immortality, the self (understood as a linear series of subjective experiences, each of which is its own subject) does not continue after the death of the brain, but the experiences nonetheless influence all that comes afterward, however negligible. Objective immortality thus understood can also include the idea that the experiences are remembered (and thus affect) God who is, as it were, the Deep Memory of the universe (Whitehead's Consequent Nature of God). Here the experiences, and the momentary subjects to whom they belong, would not fade in importance, but be valued everlastingly. "I" would not live on after my death, but memories of me, on God's part, would survive and be woven into the beauty of God's ongoing life. Thus, there are two kinds of objective immortality: objective immortality in the world and objective immortality in God.

Subjective immortality, on the other hand, is the continuation of the self after the death of the brain, whereby the self undergoes a continuing journey. This journey may or may not be everlasting; it may be "immortal" in the sense of having no end, or it may be "immortal" in a metaphorical sense, as surviving the death of the brain and continuing for a finite duration. David Griffin argues for subjective immortality but does not spell out the particular form it would take, saying that direct and indirect evidence from parapsychology points to its plausibility and perhaps even its probability. Please note that all these kinds of immortality, objective and subjective, may be "true" from a process perspective.

If subjective immortality, or at least a continuation of the self's journey, is a reality, God would be at work in the journey after death no less than in the journey prior to death: as an indwelling lure toward the fulness of life relative to the situation at hand (through initial aims) and as a companion in the journey, sharing in the sufferings and joys. There could be spiritual growth after death: a soul-gentling.

- Jay McDaniel, 6/24/2022

Life after Death: A Reflection

by John Cobb

Question:

Can you explain the Process view of our ‘life after physical death.’ Are our satisfactions resurrected into God and do they grow into what they could be in God’s aim? Will we be able then to grow into God’s aim?

from Process and Faith: October 1999

Dr. Cobb’s Response

The question asked this month is more specific than the general topic of life after physical death. It is about the Consequent Nature of God and what it means that we are taken up into this. “Are our satisfactions resurrected into God and do they grow into what they could be in God’s aim? Will we be able then to grow into God’s aim?”

There is no one answer of process theologians to these questions. There are slight differences between Whitehead and Hartshorne, and those who follow them also have different views. Of course, no one knows.

But even if we can only have visions of what may be rather than of what certainly is, these visions are important. To be persuasive they need to be organically related to the rest of what we believe. If they are to function eschatologically, they must at some level satisfy our need to believe that life and history have meaning, that they add up in some way, that what we are and do is not simply lost forever, and that even when it is painful or seemingly vacuous, it makes some positive contribution.

This is the main point of both Whitehead and Hartshorne. Whitehead thinks it is more coherent to suppose that God has physical feelings of the world than that God only mediates pure possibilities to the world. He also thinks this belief makes contact with some very deep religious intuitions. For if God prehends us, there are good reasons to think that God’s Consequent Nature includes us far more fully and richly than even a successor moment of our own experience includes its predecessors.

There are two dimensions to this difference. First, in every prehension of my immediate past experience, some of it is omitted. Whitehead provides good reason to think that in God’s prehension, nothing, or virtually nothing, is omitted. Second, although the immediate past is felt in human experience with considerable immediacy, that is, its subjectivity functions as such, this fades rapidly. My memories of what occurred even a few minutes ago lack that immediacy. In God, there is no fading of immediacy. Each experience in its full subjective value lives on forever.

Students of Whitehead sometimes miss this emphasis on experiential immediacy in the divine life because this is said to be a doctrine of “objective” immortality. This is set over against “subjective” immortality which means that persons would continue to enjoy new experiences after death.

This distinction is real and important, and although process thought does not exclude the possibility of subjective immortality in this sense, that is not what this question is about. The point here is that the data of God’s physical feelings are our subjective experiences. It is these that live on in God in their full immediacy.

The question, however, asks for something more than this, something at which Whitehead hints. As occasions of experience are resurrected in the divine life, are they changed and do they continue to change? Specifically, do they grow into what they could be in God’s aim?

Marjorie Suchocki has gone further than any other process theologian in exploring this possibility. Her book, The End of Evil, is to be highly recommended for its speculative development of Whitehead’s hints in this direction. Her development of Whitehead’s thought is motivated by her passionate conviction that sheer everlasting perpetuation of miserable experiences is no eschatology!

I have not been able to imagine as much transformation within the divine life as does Suchocki. Nevertheless, it is clear that there is some. A creaturely occasion as felt by God is not simply what that occasion was as an act of creaturely feeling. Whereas it felt itself in a very limited context, it is felt by God in a universal context. In that context it has a meaning and role that it did not have for itself. Further, as the Consequent Nature includes more and more events lying in the future of the one in question, the meaning of the original event changes. Since God’s lures have taken account of the original event, the later events, when responsive to those lures, may have built upon the original event in positive ways upon it. Thus as time goes on the momentary experience in question may become part of the realization of aims of which it was itself unaware, even of aims that did not exist at that time.

The question remains whether this change of role and meaning affects the subjectivity of the occasion. Here my imagination breaks down, and I am disposed to answer negatively. The subjective experience prehended by God remains forever just that experience. An experience here and now may be positively affected by the assurance that God can use it beyond its merits in the larger scheme of things. But just what that use may be lies forever outside the experience.

The added element of assurance that God will do with us more than we can imagine is important. That it probably does not affect the immediacy of our lives in God need not detract from that current value. It can provide the deeper meaning required by eschatological faith.

For more on life after death in Open Horizons, see:

Five Questions People Ask

What is the soul, anyway?

For John Cobb and for other process philosophers influenced by Whitehead, the human soul is part of nature. It is natural not supernatural. Animals have souls, too. The soul is a center of experience in its continuity through time, unfolding moment by moment, including within its momentary unfolding unconscious and conscious dimensions.

When depth psychologists and neurobiologists speak of unconscious forms of experience and activity within the life of a person, process philosophers and theologians agree. Conscious experience is important in the life of a soul, but not the whole of it by any means. Much and perhaps most of our experience is unconscious. One of our tasks is to find ways of reconciling and integrating the conscious and unconscious sides of our lives.

In the lives of human beings and other animals, the soul plays a decisive role in coordinating bodily activities. Consciously and unconsciously, the soul receives influences from the body and initiates responses. The state of a soul can influence the body just as the state of a body can influence the soul; hence the truth of psychosomatic medicine. Our bodies are partly affected by the states of our souls, and our souls are partly affected by the states of our bodies.

Is the soul in the brain?

Cobb and other process philosophers and theologians believe that the soul occupies regions of the brain in such a way that the brain is a constant source of novelty for the soul. The brain is composed of a vast array of "societies" that interact with one another in incredible ways, and the soul is very much shaped by those interactions. But the momentary experience of a soul, at any given moment in its ongoing life, is not reducible to any particular portion of the brain or even to the whole of the brain understood in narrowly molecular terms. It is the lived experience of the person to whom the brain belongs, and this lived experience may include forms of feeling and perception, conscious and unconscious, that are not mediated by the physical brain. If so, the soul is still "natural" in the sense of being part of the larger web of life, but not brain-restricted.

Can the soul survive death?

There is nothing in this understanding that necessitates the view that the soul pre-exists the body or survives bodily death in subjective immortality (see above). The soul may emerge in and with the embryo, not having existed beforehand. And it may perish with the death of a brain, insofar as its experience depends on the brain for nourishment. If this is the case, the soul would have objective immortality in the world and in God, but not subjective immortality.

However, from a process perspective, the pre-existence and survival of the soul after death are metaphysical possibilities. The process cosmology understands the universe as a vast and multi-dimensional web of life, and there is nothing that precludes the pre-existence or survival of souls, human and animal, if empirical evidence points in those directions.

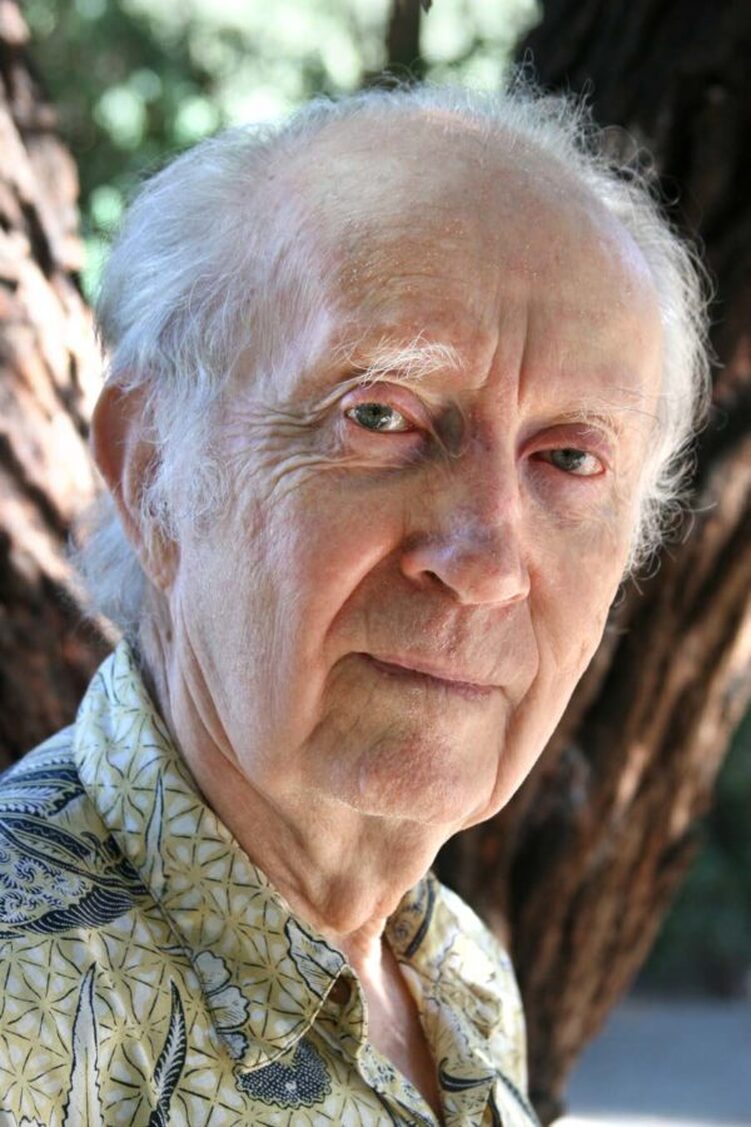

John Cobb's colleague, David Ray Griffin, has done extensive work in exploring evidence for life after death, and concludes that there is much evidence in favor of a continuing journey. For Griffin and for Cobb, it is likely that the soul undergoes a continuing journey after death. See his books below.

What about Heavens and Hells?

It is possible that, in the ongoing life of a soul, there are periods of purgation. "Hells" can be imagined as states of affairs in which a person comes to truly understand and share in the harm and pain the person inflicted upon others, seeking forgiveness. It would be a form of rehabilitation and creative transformation.

"Heavens" can be imagined as states of affairs in which a person grows into the full potential of love, awakening to connections and perhaps being reunited with loved ones. All are possible from a process perspective.

Even heavens are not necessarily permanent. It is possible that the desired end of the journey is for the soul to arrive at a definitive end, after which there is the pilgrimage of the soul as a memory in the ongoing life of God. This would be subjective immortality for a time, or, perhaps better, subjective continuation for a time, until love is fully realized, and death can be natural and holy,

Would God be at work in the life of a soul in life after death?

God is many things in process thought: an indwelling lure toward wholeness, a course of creative transformation, an eternal companion to each and all. If there is joy and suffering after death, God would share in the joy and suffering; they would 'belong to God' in some way. If there is spiritual growth in life after death, God would be an indwelling lure in the soul for the growth that is possible. From a process perspective, God never gives up on anybody. Yes, there are initial aims after death.

- Jay McDaniel

Books by David Ray Griffin exploring

Evidence for Life after Death

John Cobb on the Soul

in a Christian Natural Theology, reposted

Whitehead is remarkable among recent philosophers for his insistence that man has, or is, a soul. Furthermore, he is convinced that this doctrine has been of utmost value for Western civilization and that its recent weakening systematically undercuts the understanding of the worth of man. The understanding of the human soul is one of the truly great gifts of Plato and of Christianity, and Whitehead does not hesitate to associate his own doctrine with these sources, especially with Plato.(AI, Ch. II)

Nevertheless, Whitehead’s understanding of the human soul is different from those of Platonism and historic Christianity and is one of his most creative contributions for modern reflection. If we are to understand any aspect of Whitehead’s doctrine of man, we must begin by grasping his thought on this subject.

Perhaps the most striking differentiating feature of Whitehead’s doctrine of the soul is that it is a society rather than an individual actual entity. A moment’s reflection will show that this position follows inevitably from the distinction between individuals and societies explained in the preceding chapter. Individuals exist only momentarily. If we identified the soul with such an individual, there would be millions of souls during the lifetime of a single man.

But when we speak in Platonic or Christian terms, we think of a single soul for a single man. If we hold fast to this usage, and Whitehead basically does so, (MT 224. However, since for Whitehead identity through time is an empirical question, he allows for the possibility of a plurality of souls in a single organism.) then we must think of the soul as that society composed of all the momentary occasions of experience that make up the life history of the man. The soul is not an underlying substance undergoing accidental adventures. It is nothing but the sequence of the experiences that constitute it.

In contrast to some Christian views of the soul, it should also be noted at the outset that Whitehead’s understanding of the soul applies to the higher animals as well as to man. Wherever it is reasonable to posit a single center of experience playing a decisive role in the functioning of the organism as a whole, there it is reasonable to posit a soul. For the soul is nothing but such a center of experience in its continuity through time. The use of the term "soul" carries no connotation in Whitehead of preexistence or of life after death. There is no suggestion that the soul is some kind of supernatural element which in some way marks off man from nature and provides a special point of contact for divine activity. The soul is in every sense a part of nature, subject to the same conditions as all other natural entities. (Although this is Whitehead’s usual terminology in his later writings, in such earlier works as CN and occasionally in his later writings he speaks of nature in a more restricted sense.)

John Cobb on Life after Death

in a Christian Natural Theology, reposted

One of the questions to which the similarity and difference of animal and human souls is relevant is that of their existence after death. Whitehead dealt with this question only rarely, and then very briefly. The most important passage on the subject can be quoted.

"A belief in purely spiritual beings means, on this metaphysical theory, that there are routes of mentality in respect to which associate material routes are negligible, or entirely absent. At the present moment the orthodox belief is that for all men after death there are such routes, and that for all animals after death there are no such routes.

"Also at present it is generally held that a purely spiritual being is necessarily immortal. The doctrine here developed gives no warrant for such a belief. It is entirely neutral on the question of immortality. . . . There is no reason why such a question should not be decided on more special evidence, religious or otherwise, provided that it is trustworthy. In this lecture we are merely considering evidence with a certain breadth of extension throughout mankind. Until that evidence has yielded its systematic theory, special evidence is indefinitely weakened in its effect."(RM 110-111)

Whitehead never returned to a positive treatment of this question, largely because his own interest focused on quite a different conception of immortality.(Dial 297.) Hence, if we are to discuss this aspect of his doctrine of man, we must lean heavily upon this single fascinating passage. A number of points are clear. First, with reference to the topic of the last section, it seems that Whitehead is doubtful that so sharp a line can be drawn between animals and humans that there is real warrant for affirming total extinction of all animals and survival of all humans. Here again we see the insistent rejection of a priori and absolute distinctions. Second, Whitehead explicitly and forcefully denies that the existence of the soul is any evidence for its survival of bodily death. On the other hand, it is clear that he regards his philosophy as perfectly open to the possibility of immortality and that relevant evidence might in principle be obtained. Third, Whitehead recognizes that our response to evidence of this sort depends upon a wider structure of conviction that either opens us to the likelihood of that which is being affirmed or closes us to it.

The passage quoted is found in Religion in the Making and uses terminology slightly different from that employed in this book which depends on his later writings. In terms of the analysis offered above, we may put the question quite simply: Can the soul exist without the body? Can it have some other locus than the brain and some other function than that of presiding over the organism as a whole? In other words, can there be additional occasions in the living person without the intimate association with the body in which the soul or living person came into existence? To these questions Whitehead answers yes.(Whitehead even speculated as to the existence of other types if intelligences in far-off empty space However, the philosophical possibility that this occurs is no evidence that it in fact occurs. Furthermore, it might occur for some minutes or days or centuries and then cease. Whitehead’s private opinion was probably that it did not occur at all.

Nevertheless, in our day the philosophical assertion of the possibility of life beyond death is sufficiently striking that we will do well to consider the grounds of this openness. Since in faithfulness to Whitehead it cannot be argued that there is such life, I will only try to show why the usual philosophical and commonsense arguments for the impossibility of life after death are removed by his philosophy. These arguments stem both from anthropology and from wider cosmological considerations. They are treated below in that order.

The basic form of the anthropological argument against the possibility of life after death has already been answered in what has gone before. This argument fundamentally is that man is his body, or his body-for-itself, (Sartre) or the functioning of his body, in such a sense that it would be strictly meaningless to speak of life apart from the body. The body-for-itself obviously shares the fortunes of the body in general, and certainly the functioning of the body cannot continue without the body. Others, more correctly (from Whitehead’s point of view) , state that man is a psychophysical organism. Clearly a psychophysical organism cannot survive the death of the physical organism. From this point of view, whatever might survive could not in any case be the man.

Whitehead recognizes that language does commonly refer to the entire psychophysical organism as the man.(AI 263-264.) In this it bears testimony to the extreme intimacy of the interaction between body and soul. However, he himself ordinarily identifies the man with the soul.(PR 141.)It is the soul that is truly personal, the true subject. The body is the immediate environment of the person. Hence, the continued existence of the soul or the living person would genuinely be the continued existence of the life of the man. That there is a soul or living person, ontologically distinct from the body, is the first condition of the possibility of life after death. This distinct existence has been established in Whiteheadian terms in the preceding sections of this chapter.

The secondary anthropological objection against such life Whitehead himself probably found more weighty. This is that we have no experience of souls apart from the most intimate interaction with bodies. It is by bodies that the causal efficacy of the universe is mediated to them, and it is as the controlling forces in bodies that they have their basic functions. But whatever significance Whitehead may have attached to such considerations, he knew they were far from decisive. The soul in each momentary occasion prehends not only its environing brain but also its own past occasions of experience and the experiences of other souls.( Most important of all is the prehension of God, omitted from the text because of my effort here to limit myself to what can be said of man without reference to God. Attention will be devoted to God and to man’s experience of him in Chs. IV to VI. Insofar as White-head himself speculated about the separability of the soul from the body, the relation to God was uppermost in his mind. Note the following passage, Al 267: "How far this soul finds a support for its existence beyond the body is: -- another question. The everlasting nature of God, which in a sense is non-temporal and in another sense is temporal, may establish with the soul a peculiarly intense relationship of mutual immanence. Thus in some important sense the existence of the soul may be freed from its complete dependence on the bodily organization." Whether Whitehead actually had in mind in this passage the kind of life after death of which I am speaking or the kind of immortality in the consequent nature of God that was his usual concern I do not know.) These prehensions are not mediated by the body. Hence there is no evidence that they could not occur apart from the body. The extreme vagueness with which other souls are prehended directly in this life (PR 469. "But of course such immediate objectification [of other living persons] is also reinforced, or weakened, by routes of mediate objectification. Also pure and hybrid prehensions are integrated and thus hopelessly intermixed.") might be replaced by clarity when the mediating influences of the pure physical prehensions are removed. Such speculation makes use of no materials not directly provided by Whitehead. But it affords no evidence that the soul does live beyond death. It simply supports Whitehead’s statement that his philosophy is neutral on this question.

Even if it is accepted that the soul is such that it could exist in separation from the body, we are likely to object that there is no "place" for this existence to occur. The days when heaven could be conceived as up and hell as down are long since past (if ever, indeed, they were present for sophisticated thinkers). In the Newtonian cosmology, disembodied souls seemed thoroughly excluded from the space-time continuum. But souls, or mental substances, fitted so ill in this continuum at best, even in their embodied form, that it did not seem too strange to suppose that beyond the continuum of space and time there might be another sphere to which human souls more naturally belonged. Those who believed that somehow the soul could also be explained in terms of the little particles of matter that scurried about in space and time could not believe in any such other sphere. But for those who were convinced that mind could never be explained in terms of the motions of matter, the duality of matter and mind pointed quite naturally to the duality of this world and another, spiritual world in which space, time, and matter did not occur. Gradually, however, the sharp line that separated matter and mind gave way. Evolutionary categories brought mind into the natural world, involving it in space and time. Even if this forced the beginning of the abandonment of the pure materiality of the natural world, it also undermined the justification for conceiving of any sphere beyond this one. If minds have emerged in space and time, it is to space and time that they belong. A nonspatiotemporal mental sphere seemed no more meaningful or plausible than a nonspatiotemporal material sphere. There seemed no longer to be any "place" for life to occur after death.

Theology responded to this new situation by reviving the ancient doctrine of the resurrection of the body. If heaven could not be another sphere alongside this one, then it must be a transformation of the spatiotemporal sphere which will come at the end of time. The Pharisees, it appeared, had more truth than the Orphics. But the belief in an apocalyptic end was hard to revive, and even among the theologians who used its language, there were many who regarded the resurrection of the body more as a symbol of the wholeness of the human person, body and mind, than as a reliable prediction of the future. Outside of conservative ecclesiastical circles, the doctrine of the resurrection of the body continued to appear anachronistic. Natural theology, at any rate, could not be asked to attempt to make any sense of such a theory.

But in our situation, in which the mind or soul has been naturalized into the spatiotemporal continuum, can natural theology suggest any "place" for any kind of life after death? I am not sure that in any positive sense it can, and I am sure that I am not capable of the kind of imaginative speculation that would be required to give such a positive answer. Yet something may be said in a purely suggestive way to indicate that our commonsense inability to allow "place" for the new existence of souls is based on the limitations of our imagination and not on any knowledge we posssess about space and time. We will turn to Whitehead for the beginning of the restructuring of our imagination, on the basis of which further reflection must proceed.

The first point that must be grasped and held firmly is that we are not to think of four-dimensional space-time as a fixed reality into which all entities are placed. Space-time is a structure abstracted from the extensive relationships of actual entities. So far as what is involved in being an actual entity is concerned, there is no reason that there should be four dimensions rather than more or fewer. The world we know is four-dimensional, but this does not mean that all entities in the past and future have had or will have just this many dimensions. Indeed, it does not mean that all entities contemporary with us must have this number of dimensions, although there may be no way for us to gain cognition of any entity of a radically different sort.

Our four-dimensional space-time is the special form that the universal extensive continuum takes in our world. Every actual entity participates in this extensive continuum. But even this is not because the extensive continuum exists prior to and is determinative of the occurrence of actual entities. The extensive continuum is necessary and universal only because no actual entity can ever occur except in relation to other actual entities. Such relations may not be such as to allow for measurement, as they do in our four-dimensional world; certainly they may not have the dimensional character with which we are familiar. But some kind of extensiveness, Whitehead believes, is a function of relatedness as such.

If we try to imagine what it would be like to have no intimate relations with a body or with an external world as given to us in our sense experience, we seem to be left with a two-dimensional world. There is the dimension of successiveness, of past and future. We have memory of the past and anticipation of the future. In addition, there remains the direct experience of other living persons in mental telepathy. These persons are not experienced as related to us in a three-dimensional space but only as being external to ourselves, capable of independent, contemporary existence. Shall we call this a one-dimensional spatial relation?

Let us suppose, then, that the life of souls beyond death occurs in a two-dimensional continuum instead of the four-dimensional continuum we now know. Is it meaningful to ask" where" this two-dimensional continuum exists? Such a question can only mean, How is it related to our four-dimensional continuum according to the terms of that four-dimensional continuum? And perhaps, in those terms, no answer is possible. However, if there are relations between events in a two-dimensional continuum and events in a four-dimensional continuum, then those relations too must participate in some extensive character. Perhaps, therefore, in some mysterious sense, there is an answer, but I for one am unable to think in such terms.

For the speculations I have just outlined, I can claim no direct support from Whitehead. He does make clear that the relation of an occasion to the mental pole of other occasions does not participate in the limitations that I take to be decisive for our understanding of a three-dimensional space. (SMW 216; PR 165, 469; AI 318.) He does affirm that even now there may be occasions of experience participating in an order wholly different from the one we know. (MT 78, 212. Whitehead anticipates the gradual emergence of a new cosmic epoch in which the physical will play a lesser role and the mental a larger one. [RM 160; ESP 90.]) He repeatedly emphasizes the contingency of the special kind of space-time to which we are accustomed.(SMW 232; PR 140, 442.) But beyond this the speculation is my own.

Even if my speculations are fully warranted by Whitehead’s understanding of the extensive continuum, it should be clearly understood that these considerations argue only for the possibility of life after death, not at all for its actuality. There is nothing about the nature of the soul or of the cosmos that demands the continued existence of the living person. If man continues to exist beyond death, it can be only as a new gift of life, and whether such a gift is given is beyond the province of natural theology to inquire.