|

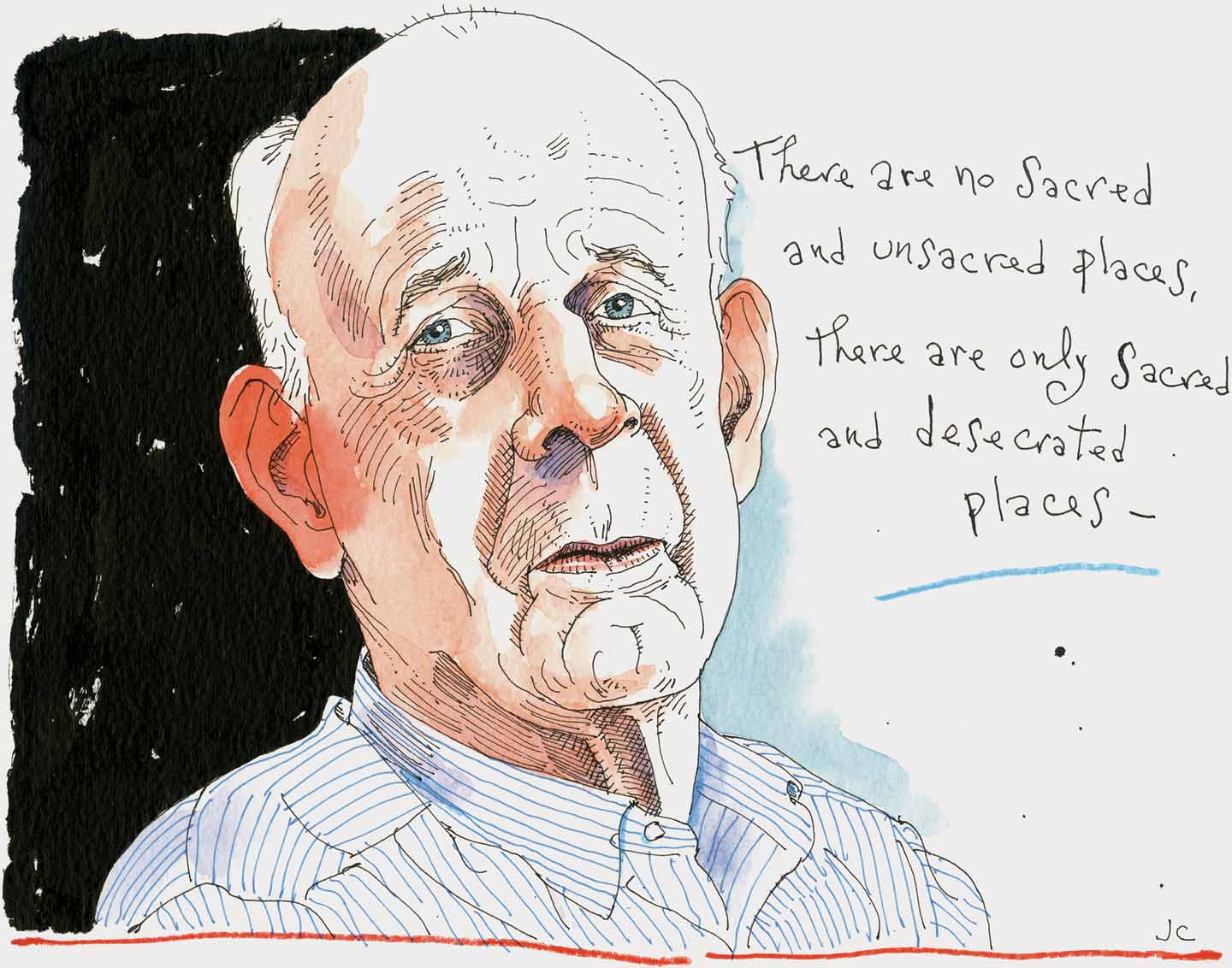

| Wendell Berry |

|

| Wendell Berry |

|

| Illustration by Joe Ciardiello |

Jedediah Britton-Purdy teaches at Columbia Law School. His new book, This Land Is Our Land: The Struggle for a New Commonwealth, will appear this fall.

Critics and scholars have acknowledged Wendell Berry as a master of many literary genres, but whether he is writing poetry, fiction, or essays, his message is essentially the same: humans must learn to live in harmony with the natural rhythms of the earth or perish. His book The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977), which analyzes the many failures of modern, mechanized life, is one of the key texts of the environmental movement. Berry has criticized environmentalists as well as those involved with big businesses and land development. In his opinion, many environmentalists place too much emphasis on wild lands without acknowledging the importance of agriculture to our society. Berry strongly believes that small-scale farming is essential to healthy local economies, and that strong local economies are essential to the survival of the species and the wellbeing of the planet. In an interview with New Perspectives Quarterly editor Marilyn Berlin Snell, Berry explained: “Today, local economies are being destroyed by the ‘pluralistic,’ displaced, global economy, which has no respect for what works in a locality. The global economy is built on the principle that one place can be exploited, even destroyed, for the sake of another place.”

Berry further believes that traditional values, such as marital fidelity and strong community ties, are essential for the survival of humankind. In his view, the disintegration of communities can be traced to the rise of agribusiness: large-scale farming under the control of giant corporations. Besides relying on chemical pesticides and fertilizers, promoting soil erosion, and causing depletion of ancient aquifers, agribusiness has driven countless small farms out of existence and destroyed local communities in the process. In a New Perspectives Quarterly interview Berry commented that such large-scale agriculture is morally as well as environmentally unacceptable: “We must support what supports local life, which means community, family, household life—the moral capital our larger institutions have to come to rest upon. If the larger institutions undermine the local life, they destroy that moral capital just exactly as the industrial economy has destroyed the natural capital of localities—soil fertility and so on. Essential wisdom accumulates in the community much as fertility builds in the soil.”

Berry’s themes are reflected in his life. As a young man, he spent time in California, Europe, and New York City. Eventually, however, he returned to the Kentucky land that had been settled by his forebears in the early 19th century. He taught for many years at the University of Kentucky, but eventually resigned in favor of full-time farming. He uses horses to work his land and employs organic methods of fertilization and pest control; he also worked as a contributing editor to New Farm Magazine and Organic Gardening and Farming, which have published his poetry as well as his agricultural treatises.

It was as a poet that Berry first gained literary recognition. In volumes such as The Country of Marriage (1973), Farming: A Handbook (1970), Openings: Poems (1968), and The Broken Ground (1964), he wrote of the countryside, the turning of the seasons, the routines of the farm, the life of the family, and the spiritual aspects of the natural world. Reviewing Collected Poems, 1957-1982, New York Times Book Review contributor David Ray called Berry’s style “resonant” and “authentic,” and claimed that the poet “can be said to have returned American poetry to a Wordsworthian clarity of purpose. ... There are times when we might think he is returning us to the simplicities of John Clare or the crustiness of Robert Frost. ... But, as with every major poet, passages in which style threatens to become a voice of its own suddenly give way, like the sound of chopping in a murmurous forest, to lines of power and memorable resonance. Many of Mr. Berry’s short poems are as fine as any written in our time.”

It is perhaps Berry’s essays that have brought him the greatest broad readership. In one of his most popular early collections, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, he argues that agriculture is the foundation of America’s greater culture. He makes a strong case against the U.S. government’s agricultural policy, which promotes practices leading to overproduction, pollution, and soil erosion. Dictionary of Literary Biography contributor Leon V. Driskell termed The Unsettling of America “an apocalyptic book that places in bold relief the ecological and environmental problems of the American nation.”

Another essay collection, Recollected Essays, 1965-1980, has been compared by several critics to Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. Charles Hudson, writing in the Georgia Review, noted that, “like Thoreau, one of Berry’s fundamental concerns is working out a basis for living a principled life. And like Thoreau, in his quest for principles Berry has chosen to simplify his life, and much of what he writes about is what has attended this simplification, as well as a criticism of modern society from the standpoint of this simplicity.”

In Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community: Eight Essays (1993), Berry continues to berate those who carelessly exploit the natural environment and damage the underlying moral fabric of communities. David Rains Wallace observed in the San Francisco Review of Books, “There’s no living essayist better than Wendell Berry. His prose is exemplary of the craftsmanship he advocates. It’s like master cabinetry or Shaker furniture, drawing elegance from precision and grace from simplicity.” Wallace allowed that at times, “Berry may overestimate agriculture’s ability to assure order and stability,” yet he maintained that the author’s “attempts to integrate ecological and agricultural thinking remain of the first importance.”

Life Is a Miracle: An Essay against Modern Superstition (2000) addresses the assumption, held by many, that science will provide solutions to all the world’s problems and mysteries. Berry conceived this book as a rebuttal to prominent Harvard University biologist Edward O. Wilson’s Consilience, which put forth as a thesis the overarching power of science. Wilson Quarterly contributor Gregg Easterbrook called Berry’s book “a nuanced and thought-provoking critique,” while Washington Monthly reviewer Bill McKibben observed that “Berry offers a rich variety of responses, never intimidated by the scientific prowess of his rival.” Jonathan Z. Larsen suggested in the Amicus Journal, though, that perhaps “Wilson has made too convenient a whipping boy,” and noted that Wilson and Berry have taken some similar stands, with both voicing great concern about the environment. Larsen also maintained that Berry needs to provide more detailed prescriptions for achieving his ideal society, one filled with reverence for one’s land and community. Larsen had praise for the book as well, especially for Berry’s writing style, which works at “winning the reader over almost as much through poetry as through logic.”

Berry’s Citizenship Papers (2003) characteristically focuses on agrarian concerns, but also turns its attention to the post-9/11 world in several of its 19 essays. “A Citizen’s Response to the New National Security Strategy” focuses on the U.S. government’s response to terrorist threats via the Patriotism Act; originally published in the New York Times, the four-part statement “probes the definitions of terrorism and security; the role of a government in combating evil; national security based on charity, civility, independence, true patriotism, and rule of law; and the failure of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam to reject war as a vehicle to peace,” explained Sojourners contributor Rose Marie Berger. In Booklist Ray Olson dubbed the author “one of English’s finest stylists, as perspicuous as T.H. Huxley at his best and as perspicacious as John Ruskin at his.” While Olson maintained that Berry adopts an approach to America’s ills “embracing life and community,” a Kirkus contributor wrote that in the “clangor of worries” echoing in Citizenship Papers Berry presents readers with “the antidotes of civility, responsibility, curiosity, skill, kindness, and an awareness of the homeplace.”

Farming and community are central to Berry’s fiction as well as his poetry and essays. Most of his novels and short stories are set in the fictional Kentucky town of Port William. Like his real-life home town, Port Royal, Port William is a long-established farming community situated near the confluence of the Ohio and Kentucky Rivers. In books such as Jayber Crow: The Life Story of Jayber Crow, Barber, of the Port William Membership (2000), The Wild Birds: Six Stories of the Port William Membership (1986), Nathan Coulter: A Novel (1985), and A Place on Earth: A Novel (1983), Berry presents the lives of seven generations of farm families. Although Fidelity: Five Stories (1992) examines Port William in the early 1990s, most of Berry’s narratives about the community take place in the first half of the 20th century; as Dictionary of Literary Biography contributor Gary Tolliver explained, “This represents the final days of America’s traditional farm communities just prior to the historically critical period when they began to break apart under the influence of technological and economic forces at the end of World War II.” Connecting all the stories is the theme of stewardship of the land, which Tolliver said is “often symbolized as interlocking marriages between a man and his family, his community, and the land.” What emerges, Los Angeles Times Book Review contributor Noel Perrin commented, “is a wounded but still powerful culture.”

Jayber Crow, dealing in part with the title character’s unrequited love for a married woman, also “strives for something greater, becoming nothing less than a sad and sweeping elegy for the idea of community, a horrifying signal of what we lost in the 20th century in the name of economic and social progress,” related Dean Bakopoulos in the Progressive. World and I reviewer Donald Secreast observed that this novel’s “basic building block is the recurring metaphor of place as character, a concern that also dominates Berry’s nonfiction and poetry. ... The relationship between landscape and personality is the core concern of Berry’s campaign to make people more responsible, more accountable for the effects their lifestyles have on local environments.” A flaw Secreast saw in Jayber Crow is the sketchy characterization of women and the lack of importance attached to their role in the community. While rural societies have traditionally been male-dominated, Secreast noted, Berry’s Port William seems to be less a reflection of rural life as it once existed than a portrayal of rural life as it should be, or should have been. “So if he’s not being nostalgic, why should he be bound by the actual dynamics of a real rural community?” Secreast wrote. “Why must Jayber Crow, despite his sensitivity, insist upon his marginalization from the womanhood of Port William?”

On the other hand, Hannah Coulter: A Novel (2004) centers fully on Port William life from a woman’s perspective. In the style of a memoir, Hannah muses on her life in a countryside that she never expected to change. Hannah’s first marriage in 1940 leaves her a widow of World War II and a single mother. Her subsequent marriage to farmer Nathan Coulter ensues, enriching her life with additional children, none of whom remain on the land to work the family farm. Will Nathan’s death mark the end of life as Hannah knew it and as she presumed it would remain? A Publishers Weekly contributor complimented Berry for his “delicate, shimmering prose” and recommended the novel as “an impassioned, literary vision of American rural life and values.” In similar fashion, a Kirkus Reviews writer called Hannah Coulter “a kind of elegy for the starkly beautiful country life that ... faded into history, victim of economic and social change.”

For a more general overview of life in Port William, readers can immerse themselves in That Distant Land: The Collected Stories of Wendell Berry. The stories, which include four not previously published, span a century in the life of the fictional farming community. The locale connects its diverse inhabitants—man, woman, farmer, teacher, lawyer, each struggling in his or her own way to maintain the simple lifestyle of times almost gone by. “Berry is an American treasure,” wrote Ann H. Fisher in Library Journal review of the collection. A contributor to Publishers Weekly observed that the author’s “feel for the inner lives of his quirky rural characters makes for many memorable portraits.”

Berry’s writing style varies greatly from one book to the next. Nathan Coulter, for example, is an example of the highly stylized, formal, spare prose that dominated the late 1950s, while A Place on Earth was described by Tolliver as “long, brooding, episodic” and “more a document of consciousness than a conventional novel.” Several critics have praised Berry’s fiction, both for the quality of his prose and for the way he brings his concerns for farming and community to life in his narratives. As Gregory L. Morris stated in Prairie Schooner, “Berry places his emphasis upon the rightness of relationships—relationships that are elemental, inherent, inviolable. ... Berry’s stories are constructed of humor, of elegy, of prose that carries within it the cadences of the hymn. The narrative voice most successful in Berry’s novels ... is the voice of the elegist, praising and mourning a way of life and the people who have traced that way in their private and very significant histories.”

Considering Berry’s body of work, Charles Hudson pointed out the author’s versatility and commended him for his appreciation of the plain things in life. “In an age when many writers have committed themselves to their ‘specialty’—even though doing so can lead to commercialism, preciousness, self-indulgence, social irresponsibility, or even nihilism—Berry has refused to specialize,” Hudson wrote in the Georgia Review. “He is a novelist, a poet, an essayist, a naturalist, and a small farmer. He has embraced the commonplace and has ennobled it.”

Since the time of Plato and Aristotle, classical ontology has posited ordinary world reality as constituted of enduring substances, to which transient processes are ontologically subordinate, if they are not denied. If Socrates changes, becoming sick, Socrates is still the same (the substance of Socrates being the same), and change (his sickness) only glides over his substance: change is accidental, and devoid of primary reality, whereas the substance is essential.

Philosophers who appeal to process rather than substance include Heraclitus, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson, Martin Heidegger, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, Alfred North Whitehead, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Thomas Nail, Alfred Korzybski, R. G. Collingwood, Alan Watts, Robert M. Pirsig, Roberto Mangabeira Unger, Charles Hartshorne, Arran Gare, Nicholas Rescher, Colin Wilson, Tim Ingold, Bruno Latour, William E. Connolly, and Gilles Deleuze. In physics, Ilya Prigogine[2] distinguishes between the "physics of being" and the "physics of becoming". Process philosophy covers not just scientific intuitions and experiences, but can be used as a conceptual bridge to facilitate discussions among religion, philosophy, and science.[3][4][original research?]

Process philosophy is sometimes classified as closer to Continental philosophy than analytic philosophy, because it is usually only taught in Continental departments.[5] However, other sources state that process philosophy should be placed somewhere in the middle between the poles of analytic versus Continental methods in contemporary philosophy.[6][7]

Heraclitus proclaimed that the basic nature of all things is change.

The quotation from Heraclitus appears in Plato's Cratylus twice; in 401d as:[8]

τὰ ὄντα ἰέναι τε πάντα καὶ μένειν οὐδέν

Ta onta ienai te panta kai menein ouden

"All entities move and nothing remains still"

and in 402a[9]

"πάντα χωρεῖ καὶ οὐδὲν μένει" καὶ "δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης"

Panta chōrei kai ouden menei kai dis es ton auton potamon ouk an embaies

"Everything changes and nothing remains still ... and ... you cannot step twice into the same stream"[10]

Heraclitus considered fire as the most fundamental element.

"All things are an interchange for fire, and fire for all things, just like goods for gold and gold for goods."[11]

The following is an interpretation of Heraclitus's concepts into modern terms by Nicholas Rescher.

"...reality is not a constellation of things at all, but one of processes. The fundamental "stuff" of the world is not material substance, but volatile flux, namely "fire", and all things are versions thereof (puros tropai). Process is fundamental: the river is not an object, but a continuing flow; the sun is not a thing, but an enduring fire. Everything is a matter of process, of activity, of change (panta rhei)."[12]

An early expression of this viewpoint is in Heraclitus's fragments. He posits strife, ἡ ἔρις (strife, conflict), as the underlying basis of all reality defined by change.[13] The balance and opposition in strife were the foundations of change and stability in the flux of existence.

In early twentieth century, the philosophy of mathematics was undertaken to develop mathematics as an airtight, axiomatic system in which every truth could be derived logically from a set of axioms. In the foundations of mathematics, this project is variously understood as logicism or as part of the formalist program of David Hilbert. Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell attempted to complete, or at least facilitate, this program with their seminal book Principia Mathematica, which purported to build a logically consistent set theory on which to found mathematics. After this, Whitehead extended his interest to natural science, which he held needed a deeper philosophical basis. He intuited that natural science was struggling to overcome a traditional ontology of timeless material substances that does not suit natural phenomena. According to Whitehead, material is more properly understood as 'process'. In 1929, he produced the most famous work of process philosophy, Process and Reality,[14] continuing the work begun by Hegel but describing a more complex and fluid dynamic ontology.

Process thought describes truth as "movement" in and through substance (Hegelian truth), rather than substances as fixed concepts or "things" (Aristotelian truth). Since Whitehead, process thought is distinguished from Hegel in that it describes entities that arise or coalesce in becoming, rather than being simply dialectically determined from prior posited determinates. These entities are referred to as complexes of occasions of experience. It is also distinguished in being not necessarily conflictual or oppositional in operation. Process may be integrative, destructive or both together, allowing for aspects of interdependence, influence, and confluence, and addressing coherence in universal as well as particular developments, i.e., those aspects not befitting Hegel's system. Additionally, instances of determinate occasions of experience, while always ephemeral, are nonetheless seen as important to define the type and continuity of those occasions of experience that flow from or relate to them.

Alfred North Whitehead began teaching and writing on process and metaphysics when he joined Harvard University in 1924.[15]

In his book Science and the Modern World (1925), Whitehead noted that the human intuitions and experiences of science, aesthetics, ethics, and religion influence the worldview of a community, but that in the last several centuries science dominates Western culture. Whitehead sought a holistic, comprehensive cosmology that provides a systematic descriptive theory of the world which can be used for the diverse human intuitions gained through ethical, aesthetic, religious, and scientific experiences, and not just the scientific.[3]

Whitehead's influences were not restricted to philosophers or physicists or mathematicians. He was influenced by the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941), whom he credits along with William James and John Dewey in the preface to Process and Reality.[14]

For Whitehead, metaphysics is about logical frameworks for the conduct of discussions of the character of the world. It is not directly and immediately about facts of nature, but only indirectly so, in that its task is to explicitly formulate the language and conceptual presuppositions that are used to describe the facts of nature. Whitehead thinks that discovery of previously unknown facts of nature can in principle call for reconstruction of metaphysics.[16]

The process metaphysics elaborated in Process and Reality[14] posits an ontology which is based on the two kinds of existence of an entity, that of actual entity and that of abstract entity or abstraction, also called 'object'.[17]

Actual entity is a term coined by Whitehead to refer to the entities that really exist in the natural world.[18] For Whitehead, actual entities are spatiotemporally extended events or processes.[19] An actual entity is how something is happening, and how its happening is related to other actual entities.[19] The actually existing world is a multiplicity of actual entities overlapping one another.[19]

The ultimate abstract principle of actual existence for Whitehead is creativity. Creativity is a term coined by Whitehead to show a power in the world that allows the presence of an actual entity, a new actual entity, and multiple actual entities.[19] Creativity is the principle of novelty.[18] It is manifest in what can be called 'singular causality'. This term may be contrasted with the term 'nomic causality'. An example of singular causation is that I woke this morning because my alarm clock rang. An example of nomic causation is that alarm clocks generally wake people in the morning. Aristotle recognizes singular causality as efficient causality. For Whitehead, there are many contributory singular causes for an event. A further contributory singular cause of my being awoken by my alarm clock this morning was that I was lying asleep near it till it rang.

An actual entity is a general philosophical term for an utterly determinate and completely concrete individual particular of the actually existing world or universe of changeable entities considered in terms of singular causality, about which categorical statements can be made. Whitehead's most far-reaching and radical contribution to metaphysics is his invention of a better way of choosing the actual entities. Whitehead chooses a way of defining the actual entities that makes them all alike, qua actual entities, with a single exception.

For example, for Aristotle, the actual entities were the substances, such as Socrates. Besides Aristotle's ontology of substances, another example of an ontology that posits actual entities is in the monads of Leibniz, which are said to be 'windowless'.

|

| #965: Primer on Whitehead’s Process Philosophy as a Paradigm Shift & Foundation for Experiential Design, by Matthew Segall: "Footnotes to Plato" |

For Whitehead's ontology of processes as defining the world, the actual entities exist as the only fundamental elements of reality.

The actual entities are of two kinds, temporal and atemporal.

With one exception, all actual entities for Whitehead are temporal and are occasions of experience (which are not to be confused with consciousness). An entity that people commonly think of as a simple concrete object, or that Aristotle would think of as a substance, is, in this ontology, considered to be a temporally serial composite of indefinitely many overlapping occasions of experience. A human being is thus composed of indefinitely many occasions of experience.

The one exceptional actual entity is at once both temporal and atemporal: God. He is objectively immortal, as well as being immanent in the world. He is objectified in each temporal actual entity; but He is not an eternal object.

The occasions of experience are of four grades. The first grade comprises processes in a physical vacuum such as the propagation of an electromagnetic wave or gravitational influence across empty space. The occasions of experience of the second grade involve just inanimate matter; "matter" being the composite overlapping of occasions of experience from the previous grade. The occasions of experience of the third grade involve living organisms. Occasions of experience of the fourth grade involve experience in the mode of presentational immediacy, which means more or less what are often called the qualia of subjective experience. So far as we know, experience in the mode of presentational immediacy occurs in only more evolved animals. That some occasions of experience involve experience in the mode of presentational immediacy is the one and only reason why Whitehead makes the occasions of experience his actual entities; for the actual entities must be of the ultimately general kind. Consequently, it is inessential that an occasion of experience have an aspect in the mode of presentational immediacy; occasions of the grades one, two, and three, lack that aspect.

There is no mind-matter duality in this ontology, because "mind" is simply seen as an abstraction from an occasion of experience which has also a material aspect, which is of course simply another abstraction from it; thus the mental aspect and the material aspect are abstractions from one and the same concrete occasion of experience. The brain is part of the body, both being abstractions of a kind known as persistent physical objects, neither being actual entities. Though not recognized by Aristotle, there is biological evidence, written about by Galen,[20] that the human brain is an essential seat of human experience in the mode of presentational immediacy. We may say that the brain has a material and a mental aspect, all three being abstractions from their indefinitely many constitutive occasions of experience, which are actual entities.

Inherent in each actual entity is its respective dimension of time. Potentially, each Whiteheadean occasion of experience is causally consequential on every other occasion of experience that precedes it in time, and has as its causal consequences every other occasion of experience that follows it in time; thus it has been said that Whitehead's occasions of experience are 'all window', in contrast to Leibniz's 'windowless' monads. In time defined relative to it, each occasion of experience is causally influenced by prior occasions of experiences, and causally influences future occasions of experience. An occasion of experience consists of a process of prehending other occasions of experience, reacting to them. This is the process in process philosophy.

Such process is never deterministic. Consequently, free will is essential and inherent to the universe.

The causal outcomes obey the usual well-respected rule that the causes precede the effects in time. Some pairs of processes cannot be connected by cause-and-effect relations, and they are said to be spatially separated. This is in perfect agreement with the viewpoint of the Einstein theory of special relativity and with the Minkowski geometry of spacetime.[21] It is clear that Whitehead respected these ideas, as may be seen for example in his 1919 book An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge[22] as well as in Process and Reality. In this view, time is relative to an inertial reference frame, different reference frames defining different versions of time.

The actual entities, the occasions of experience, are logically atomic in the sense that an occasion of experience cannot be cut and separated into two other occasions of experience. This kind of logical atomicity is perfectly compatible with indefinitely many spatio-temporal overlaps of occasions of experience. One can explain this kind of atomicity by saying that an occasion of experience has an internal causal structure that could not be reproduced in each of the two complementary sections into which it might be cut. Nevertheless, an actual entity can completely contain each of indefinitely many other actual entities.

Another aspect of the atomicity of occasions of experience is that they do not change. An actual entity is what it is. An occasion of experience can be described as a process of change, but it is itself unchangeable.

The reader should bear in mind that the atomicity of the actual entities is of a simply logical or philosophical kind, thoroughly different in concept from the natural kind of atomicity that describes the atoms of physics and chemistry.

Whitehead's theory of extension was concerned with the spatio-temporal features of his occasions of experience. Fundamental to both Newtonian and to quantum theoretical mechanics is the concept of momentum. The measurement of a momentum requires a finite spatiotemporal extent. Because it has no finite spatiotemporal extent, a single point of Minkowski space cannot be an occasion of experience, but is an abstraction from an infinite set of overlapping or contained occasions of experience, as explained in Process and Reality.[14] Though the occasions of experience are atomic, they are not necessarily separate in extension, spatiotemporally, from one another. Indefinitely many occasions of experience can overlap in Minkowski space.

Nexus is a term coined by Whitehead to show the network actual entity from universe. In the universe of actual entities spread[18] actual entity. Actual entities are clashing with each other and form other actual entities.[19] The birth of an actual entity based on an actual entity, actual entities around him referred to as nexus.[18]

An example of a nexus of temporally overlapping occasions of experience is what Whitehead calls an enduring physical object, which corresponds closely with an Aristotelian substance. An enduring physical object has a temporally earliest and a temporally last member. Every member (apart from the earliest) of such a nexus is a causal consequence of the earliest member of the nexus, and every member (apart from the last) of such a nexus is a causal antecedent of the last member of the nexus. There are indefinitely many other causal antecedents and consequences of the enduring physical object, which overlap, but are not members, of the nexus. No member of the nexus is spatially separate from any other member. Within the nexus are indefinitely many continuous streams of overlapping nexūs, each stream including the earliest and the last member of the enduring physical object. Thus an enduring physical object, like an Aristotelian substance, undergoes changes and adventures during the course of its existence.

In some contexts, especially in the theory of relativity in physics, the word 'event' refers to a single point in Minkowski or in Riemannian space-time. A point event is not a process in the sense of Whitehead's metaphysics. Neither is a countable sequence or array of points. A Whiteheadian process is most importantly characterized by extension in space-time, marked by a continuum of uncountably many points in a Minkowski or a Riemannian space-time. The word 'event', indicating a Whiteheadian actual entity, is not being used in the sense of a point event.

Whitehead's abstractions are conceptual entities that are abstracted from or derived from and founded upon his actual entities. Abstractions are themselves not actual entities. They are the only entities that can be real but are not actual entities. This statement is one form of Whitehead's 'ontological principle'.

An abstraction is a conceptual entity that refers to more than one single actual entity. Whitehead's ontology refers to importantly structured collections of actual entities as nexuses of actual entities. Collection of actual entities into a nexus emphasizes some aspect of those entities, and that emphasis is an abstraction, because it means that some aspects of the actual entities are emphasized or dragged away from their actuality, while other aspects are de-emphasized or left out or left behind.

'Eternal object' is a term coined by Whitehead. It is an abstraction, a possibility, or pure potential. It can be ingredient into some actual entity.[18] It is a principle that can give a particular form to an actual entity.[19][23]

Whitehead admitted indefinitely many eternal objects. An example of an eternal object is a number, such as the number 'two'. Whitehead held that eternal objects are abstractions of a very high degree of abstraction. Many abstractions, including eternal objects, are potential ingredients of processes.

For Whitehead, besides its temporal generation by the actual entities which are its contributory causes, a process may be considered as a concrescence of abstract ingredient eternal objects. God enters into every temporal actual entity.

Whitehead's ontological principle is that whatever reality pertains to an abstraction is derived from the actual entities upon which it is founded or of which it is comprised.

Concrescence is a term coined by Whitehead to show the process of jointly forming an actual entity that was without form, but about to manifest itself into an entity Actual full (satisfaction) based on datums or for information on the universe.[18] The process of forming an actual entity is the case based on the existing datums. Concretion process can be regarded as subjectification process.[19]

Datum is a term coined by Whitehead to show the different variants of information possessed by actual entity. In process philosophy, datum is obtained through the events of concrescence. Every actual entity has a variety of datum.[18][19]

Whitehead is not an idealist in the strict sense.[which?] Whitehead's thought may be regarded as related to the idea of panpsychism (also known as panexperientialism, because of Whitehead's emphasis on experience).[24]

Whitehead's philosophy is very complex, subtle and nuanced and in order to comprehend his thinking regarding what is commonly referred to by many religions as "God", it is recommended that one read from Process and Reality Corrected Edition, wherein regarding "God" the authors elaborate Whitehead's conception.

"He is the unconditioned actuality of conceptual feeling at the base of things; so that by reason of this primordial actuality, there is an order in the relevance of eternal objects to the process of creation (343 of 413) (Location 7624 of 9706 Kindle ed.) Whitehead continues later with, "The particularities of the actual world presuppose it ; while it merely presupposes the general metaphysical character of creative advance, of which it is the primordial exemplification (344 of 413) (Location 7634 of 9706 Kindle Edition)."

Process philosophy, might be considered according to some theistic forms of religion to give God a special place in the universe of occasions of experience. Regarding Whitehead's use of the term "occasions" in reference to "God", it is explained in Process and Reality Corrected Edition that

"'Actual entities'-also termed 'actual occasions'-are the final real things of which the world is made up. There is no going behind actual entities to find anything [28] more real. They differ among themselves: God is an actual entity, and so is the most trivial puff of existence in far-off empty space. But, though there are gradations of importance, and diversities of function, yet in the principles which actuality exemplifies all are on the same level. The final facts are, all alike, actual entities; and these actual entities are drops of experience, complex and interdependent.

It also can be assumed within some forms of theology that a God encompasses all the other occasions of experience but also transcends them and this might lead to it being argued that Whitehead endorses some form of panentheism.[25] Since, it is argued theologically, that "free will" is inherent to the nature of the universe, Whitehead's God is not omnipotent in Whitehead's metaphysics.[26] God's role is to offer enhanced occasions of experience. God participates in the evolution of the universe by offering possibilities, which may be accepted or rejected. Whitehead's thinking here has given rise to process theology, whose prominent advocates include Charles Hartshorne, John B. Cobb, Jr., and Hans Jonas, who was also influenced by the non-theological philosopher Martin Heidegger. However, other process philosophers have questioned Whitehead's theology, seeing it as a regressive Platonism.[27]

Whitehead enumerated three essential natures of God. The primordial nature of God consists of all potentialities of existence for actual occasions, which Whitehead dubbed eternal objects. God can offer possibilities by ordering the relevance of eternal objects. The consequent nature of God prehends everything that happens in reality. As such, God experiences all of reality in a sentient manner. The last nature is the superjective. This is the way in which God's synthesis becomes a sense-datum for other actual entities. In some sense, God is prehended by existing actual entities.[28]

In plant morphology, Rolf Sattler developed a process morphology (dynamic morphology) that overcomes the structure/process (or structure/function) dualism that is commonly taken for granted in biology. According to process morphology, structures such as leaves of plants do not have processes, they are processes.[29][30]

In evolution and in development, the nature of the changes of biological objects are considered by many authors to be more radical than in physical systems. In biology, changes are not just changes of state in a pre-given space, instead the space and more generally the mathematical structures required to understand object change over time.[31][32]

With its perspective that everything is interconnected, that all life has value, and that non-human entities are also experiencing subjects, process philosophy has played an important role in discourse on ecology and sustainability. The first book to connect process philosophy with environmental ethics was John B. Cobb, Jr.'s 1971 work, Is It Too Late: A Theology of Ecology.[33] In a more recent book (2018) edited by John B. Cobb, Jr. and Wm. Andrew Schwartz, Putting Philosophy to Work: Toward an Ecological Civilization[34] contributors explicitly explore the ways in which process philosophy can be put to work to address the most urgent issues facing our world today, by contributing to a transition toward an ecological civilization. That book emerged from the largest international conference held on the theme of ecological civilization (Seizing an Alternative: Toward an Ecological Civilization) which was organized by the Center for Process Studies in June 2015. The conference brought together roughly 2,000 participants from around the world and featured such leaders in the environmental movement as Bill McKibben, Vandana Shiva, John B. Cobb, Jr., Wes Jackson, and Sheri Liao.[35] The notion of ecological civilization is often affiliated with the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead—especially in China.[36]

Somewhat earlier, exploration of mathematical practice and quasi-empiricism in mathematics from the 1950s to 1980s had sought alternatives to metamathematics in social behaviours around mathematics itself: for instance, Paul Erdős's simultaneous belief in Platonism and a single "big book" in which all proofs existed, combined with his personal obsessive need or decision to collaborate with the widest possible number of other mathematicians. The process, rather than the outcomes, seemed to drive his explicit behaviour and odd use of language, as if the synthesis of Erdős and collaborators in seeking proofs, creating sense-datum for other mathematicians, was itself the expression of a divine will. Certainly, Erdős behaved as if nothing else in the world mattered, including money or love, as emphasized in his biography The Man Who Loved Only Numbers.In the philosophy of mathematics, some of Whitehead's ideas re-emerged in combination with cognitivism as the cognitive science of mathematics and embodied mind theses.

Several fields of science and especially medicine seem[vague] to make liberal use of ideas in process philosophy, notably the theory of pain and healing of the late 20th century. The philosophy of medicine began to deviate somewhat from scientific method and an emphasis on repeatable results in the very late 20th century by embracing population thinking, and a more pragmatic approach to issues in public health, environmental health and especially mental health. In this latter field, R. D. Laing, Thomas Szasz and Michel Foucault were instrumental in moving medicine away from emphasis on "cures" and towards concepts of individuals in balance with their society, both of which are changing, and against which no benchmarks or finished "cures" were very likely to be measurable.

In psychology, the subject of imagination was again explored more extensively since Whitehead, and the question of feasibility or "eternal objects" of thought became central to the impaired theory of mind explorations that framed postmodern cognitive science. A biological understanding of the most eternal object, that being the emerging of similar but independent cognitive apparatus, led to an obsession with the process "embodiment", that being, the emergence of these cognitions. Like Whitehead's God, especially as elaborated in J. J. Gibson's perceptual psychology emphasizing affordances, by ordering the relevance of eternal objects (especially the cognitions of other such actors), the world becomes. Or, it becomes simple enough for human beings to begin to make choices, and to prehend what happens as a result. These experiences may be summed in some sense but can only approximately be shared, even among very similar cognitions with identical DNA. An early explorer of this view was Alan Turing who sought to prove the limits of expressive complexity of human genes in the late 1940s, to put bounds on the complexity of human intelligence and so assess the feasibility of artificial intelligence emerging. Since 2000, Process Psychology has progressed as an independent academic and therapeutic discipline: In 2000, Michel Weber created the Whitehead Psychology Nexus: an open forum dedicated to the cross-examination of Alfred North Whitehead's process philosophy and the various facets of the contemporary psychological field.[37]

The philosophy of movement is a sub-area within process philosophy that treats processes as movements. It studies processes as flows, folds, and fields in historical patterns of centripetal, centrifugal, tensional, and elastic motion.[38] See Thomas Nail's philosophy of movement and process materialism.