A New Book from Lexington's Contemporary Whitehead Series

"Mind, Value, and Cosmos: On the Relational Nature of Ultimacy" is an investigation into the nature of ultimacy and explanation, particularly as it relates to the status of, and relationship among Mind, Value, and the Cosmos. It draws its stimulus from longstanding “axianoetic” convictions as to the ultimate status of Mind and Value in the western tradition of philosophical theology, and chiefly from the influential modern proposals of A.N. Whitehead, Keith Ward, and John Leslie. What emerges is a relational theory of ultimacy wherein Mind and Value, Possibility and Actuality, God and the World are revealed as “ultimate” only in virtue of their relationality. The ultimacy of relationality—what Whitehead calls “mutual immanence”—uniquely illuminates enduring mysteries surrounding: any and all existence, necessary divine existence, the nature of the possible, and the world as actual. As such, it casts fresh light upon the whence and why of God, the World, and their ultimate presuppositions.

Purchase from Publisher: https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781793636393...

Purchase from Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Mind-Value-Cos...

Stay up to date at: https://www.andrewmdavis.info/

Daily Life Metaphysics

I do not write this "interpretive overview" for philosophers or theologians, but rather for the other ninety-nine percent of the world. I write for house painters, pediatricians, farmers, accountants, elementary school teachers, construction workers, single moms, single dads, grandparents, and teenagers who are absorbed in daily life and trying to find their way in a crazy yet beautiful world. Andrew Davis' Mind, Value, and Cosmos can help us even if we haven't the time to read the book much less pay for it.

It is a "metaphysical work" in its way, dealing with questions of what is ultimately true and ultimately real. At first glance these may sound abstract or irrelevant, but they translate into basic questions we all ask, implicitly if not explicitly:

- Given the actual circumstance of my life, with its pleasures and pains, its joys and sufferings, its anxieties and consolations, its healthy relationships and broken relationships, are there possibilities available to me that might help me respond in a constructive and creative way?

- Are the people with whom I interact mere objects for me, or are they subjects of their own lives with minds of their own?

- Is there something like mind or value in the world around me, too, including in the hills and trees, rivers and stars? Is the whole cosmos filled with things that are worthy of respect and care? Is there intrinsic value everywhere?

- Is there anything in the universe - God - which is a companion to the whole of things and which can help guide us all?

- Does all the power in the universe lie with this God, or do I myself have power and creativity, too?

- Where does this creativity come from? Is creativity an ultimate reality, too?

- What if all of them -- God and the World, Mind and Value, Actuality and Possibility -- are ultimate in their respective ways?

- If so, would it be the case that, in some deep sense, relationality or interconnectedness is the ultimate of ultimates?

- And where, if anywhere, might I experience all of these ultimates? Are they somehow present in each present moment?

- Is the present moment ultimate, too?

These are the kinds of questions to which Andrew Davis points in Mind, Value, and Cosmos. The italicized words are Davis' own oft-used words, used throughout his book. Granted, he does not frame the questions in just this way, because he is writing for specialists, especially for scholars in philosophy and theology who are a bit more preoccupied with what is real than in how to live. But I myself am a how-to-live kind of guy. In this interpretive overview I want to do my best to bring some of Davis' ideas down earth all the while remaining true to his core insights. His book points us in the direction of a daily-life metaphysics which can benefit us all.

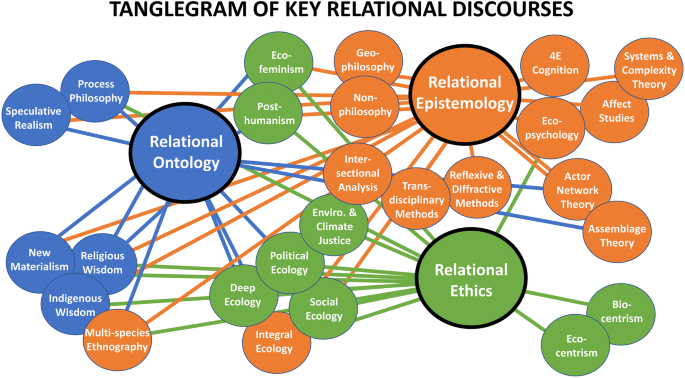

And so does the video above, itself a trailer for the book. In the spiritual alphabet of humanity used in Open Horizons and also by the Cobb Institute (borrowed from Spirituality and Practice), “A” is for attention, “C” is for connection or relationality, and “Q” is for questing. You will sense from the video that Andrew Davis is a quester who invites us to pay attention to the worlds around us and within us, and to recognize the ultimacy of relationality, for our sakes and the world's sake. In our time, unfortunately, an alternative yet dominant metaphysic reigns, itself the legacy of western modernity. This dominant worldview is a stale materialism that sees the universe as a collection of objects, not a communion of subjects. From the point of view of this worldview, value is but a creation of the human mind, and the mind itself is really but an epiphemenon, a burp, if you will, of brain chemistry, which consists of mindless particles in motion. We need to re-awaken to the communion, and Andrew Davis can help. So here goes:

Six Ideas Plus One

Six ideas weave their way through Mind, Value, and Cosmos: On the Relational Nature of Ultimacy.

- Mind

- Value

- Actuality

- Possibility

- God

- World

Davis believes that we can better understand ourselves and the world around us if we take heed of them, and that these ideas are necessary to an adequate understanding of “the mystery of existence.”

To be sure, there is more to this mystery than can be contained in any set of ideas, including these six. But the ideas are portals into that mystery. They are windows through which our minds, and perhaps also our hearts, can be grasped by the depths. Indeed, as we quest after such ideas, such portals, the agency may lie not only in our minds but also in the universe. In his words “the universe comes to question itself through us.” [But this same question might be posed by the greater whole, e.g., the "universe", of each of its parts. - re slater]

If you have been inclined to think of one and only one ultimate reality, you might want to ask which of the six is really ultimate. Or at least to think that some are more ultimate than others. For example, a monotheist might say that God is the one true ultimate and the others are merely derivative. A secularist might say that the world is the only true ultimate and that God is a mere projection of the mind.

Andrew Davis disagrees. He thinks that all six are ultimate in different ways that need not be ranked over the others. And if you ask "Well what does ultimate mean?," he offers a simple and alluring answer. Something is ultimate if it is "necessary in the nature of things." By this he means that if we truly want to be honest about the mystery of existence, we must take note of each and all of the six.

However, there is one "ultimate" that is revealed in an analysis of any and all of the six. This is the ultimacy of relationality: that is, the fact that all six depend upon the others. That is the crux of his book: the idea that relationality itself is at least as ultimate, and perhaps more ultimate, than anything else. [Relationality] is the ultimate through which God and the World, Actuality and Possibility, Mind and Value, find their ultimacy.

Contextuality

But let's go back to the six for a moment. Davis knows that in some circumstances one or another of the ultimates may be more important to us.

You'll discover this if you go to his website and look at some his poetry. One of his poems is "Insights for a Way of Life." One insight reads: "Meet at least one new person every day. Make your goal three a day for a year and see what happens: for a world without community is a high watermark of silliness. A world without friends is a wilderness for the lonely." If we follow his advice, we are awakened to the ultimacy of Possibility - in this instance the possibility of meeting new people. We experience the ultimate of Possibility in acts of imagination and anticipation, through which an as yet undecided future becomes real for us.

Another insight in the poem reads: "Suffering is not a question of 'if,' nor even 'when,' but 'how.' The 'how' question is one of orientation to, and sensitivity toward, what is opened by the suffering. Suffering brings either death or depth. The choice remains ones own. Attention to such things is a way of life." If we follow his advice, we are awakened to the ultimacy of Actuality and, in this instance, the actuality of suffering of decision, or choice, in how we respond.

The very Possibility of responding by choosing life over death shows the interplay of Possibility and Actuality - the two are fused together even as distinct. Here we have an interfusion of life as it is and life as it can be, or Actuality and Possibility. Hence the point about relationality. Actuality and Possibility are, in his words, "mutually transcedent" but also "mutually immanent," because they presuppose and depend on one another. The same goes for all six ideas identified above.

Indra's Net

How to think of this? Imagine reality on the analogy of Indra’s Net of Jewels in Mahayana Buddhism. Each jewel in the net reflects all the others and the light of each is contained in all. For Davis, each of the six ideas is a jewel in the net, each unique and yet containing and reflecting the others. Buddhists speak of the jewels in Indra's net as inter-penetrating one another. Davis, borrowing from Whitehead, speaks of the ideas as 'interfusing' one another. Let some of the jewels in the net be abstract ideas or Possibilities, and let some be Actualities, such as another person, an animal or plant, a living cell or a star in the sky. Indeed, let one jewel be God and another the World. And let one jewel be Mind and another Value. The point is that the six need each other, that they cannot be real without the others. Let their dependence on one another be imagined on the analogy of lines that connect them.

Let us also recognize that there are at least two different kinds of lines because there is a difference between (1) how ideas interpenenetrate one another and (2) how actualities do so. Ideas reflect one another through logical connections. Ideas as such are real but do not have feelings and do not make decisions. They are objects we entertain in our minds but not flesh and blood realities that we feel, touch, and know with our physical eyes and ears and hands. They are, as it were, Possibilities.

By contrast actualities interpenetrate one another through feelings and experiences. We humans are affected by the moods and feelings of others, such as their lives are part of our own emotionally and ours are part of them. See Davis' poem about sexual intimacy. He speaks of it as recriprocal worship filled with devoted allegiance and trust and adoration. Possibilities as such do not adore one another and enter into this kind of worship. But people do. There is a fundamental difference between the possibility of such intimacy as entertained in the mind, and the actuality of such intimacy as felt in mutual intimacy.

Four Kinds of Connection

Morever, there are two additional forms of relationality that must be recognized. The "relationality" of Possibilities to Actualities and that of Actualities to Possibilities. Possibilities have relations with Actualities as "lures" with evocative power of their own; and Actualities have relations with Possibilities as "agents" that actualize possibilities, enabling their qualities to be ingressed in the world. In short, we might imagine four kinds of relationality that form the 'connections' in the kind of universe Davis has in mind: actuality to actualities, possibility to possibility (or ideas to ideas), possibility to actuality,and actuality to possibility. "interfusion" or "mutual immanence" is a very general word that includes affective, existential intimacy, itself a kind of relationality, and conceptual relationality. Davis is inviting us to be mindful, and in many ways grateful, for both of these forms of relationality.

Relational Intuitions

As my example of Indra's Net suggests, the idea that relationality is ultimate is not new. Something close to what Davis means by the “ultimacy of relationality” has been a cardinal teaching of various strands of Buddhism for thousands of years. Here Nagarjuna (circa 150-250 CE) in India and Fa-Tsang (643-712 CE) in China come to mind; and more generally the Buddhist doctrine of dependent origination (pratitya-samutpada).

For practicing Buddhists, awakening to the ultimacy of inter-dependence or pratitya-samutpada has often been taken as a key to enlightenment. The awakening itself is not so much a philosophical awakening, emerging out of logical argumentation or a play of ideas, but rather an existential awakening: a flash of insight that, at best, becomes abiding light in daily life. In Mind, Value and Cosmos Davis uses the phrase relational intuitions to name this insight. Such intuitions can be evoked by all four kinds of connections identified above. And, so Davis adds, we can have a sense that relationality as such, in any and all of its forms, is itself ultimate. The Buddhist enlightenment experience can be understood as a relational intuition magnified by infinite. In Buddhism, two virtues are lifted up as paramount for spirituality in daily life: wisdom and compassion. Relational intuitions are the wisdom.

A Cosmic Bodhisattva?

While Davis' interests are by all means cross-cultural and multi-religious, Mind, Value and Cosmos is primarily Western in its references. It is preoccupied with the God of Abrahamic traditions in ways that would be almost foreign to most Buddhists. I say almost because, in fact, many Buddhists speak of heavenly spirits (bodhisattvas and buddhas) who are examples of, not exceptions to, relationality. Arguably the relational God to whom Davis points may resemble a universal Bodhisattva – not so much a self-contained monad but rather a cosmic spirit with subjective immediacy, aims and purposes of her own, who has awakened to the ultimacy of relationality, and whose very existence is partly dependent on the world she seeks to save. The relationality of Bodhisattvas notwithstanding, Davis’ interlocutors are Western not Asian. He understands his book as in a lineage of “Western philosophy and theology.” His primary interlocutors are Whitehead and two others: the Canadian philosopher John Leslie and British philosopher-and-theologian Keith Ward. The book is a dialogue between these three, with Whitehead as the most influential among them, and with Davis adding his own voice. Much of the book is devoted to this dialogue.

Existence as Lived Experience

For whom is Mind, Value, and Cosmos written? In style and substance it is written mostly for philosophers with a metaphysical bent and for philosophical theologians who enjoy the subtleties of a play with ideas. Whereas Davis' poetry focuses on lived human experience, the focus of Mind, Value and Cosmos is on philosophical notions: that is, in “conditions, presuppositions, or requirements without which there could be a universe at all.” If western philosophy has its rational and empirical sides, Mind, Value, and Cosmos seems to be on the rational side of things, which is not surprising since “Mind” is one of its central ideas. Nevertheless, Davis is also concerned with experience and with what he calls, following Whitehead, “modes of existence.” For Davis as for Whitehead, experience and existence go together. They are part of what Davis means by Actuality.

For Whitehead actuality is not an idea or presupposition in the mind. Yes, the "idea" of actuality is just such an idea, but the fact of actuality, as lived, is by not means simply an idea. In Whitehead existence is actual experience in the here-and-now. It is the lived experience of eating, sleeping, laughing, crying, hoping, worrying, struggling, yearning, playing, and sleeping - always in relation to other things, even if, as in sleeping, primarily the body and the personal and collective unconscious.

Lived experience is another word for Actuality, and it has some universals of its own. It always has a standpoint, a regional location, from which it experiences the world consciously and unconsciously. It always experiences the world by means of feelings, including what Whitehead calls 'experience in the mode of causal efficacy,' which is feeling the feelings of others. It always involves some kind of spontaneity, some kind of freedom or decision, in how it responds to what is felt. And, even in sleeping, it always creates something new and valuable. (No two dreams are alike, and dreamless sleep is filled with mental processing, so we learn from cognitive science.) Every moment of lived experience is novel, even if its novelty is primarily a repetition of past forms. Existence as such includes and requires novelty, not as a mere adjunct to actuality, but as part of the very essence of actuality.

An Axionetic Universe

In Mind, Value, and Cosmos Davis highlights the novelty. Whereas much western philosophy has been inclined to think of being as timeless and of novelty as a mere appendage of being, influenced by one of his mentors, Roland Faber, sees novelty as essential to being. Heidegger wrote the well-known book Being and Time, showing how temporality is essential to human exsitence; Davis and Faber encourage us to think in terms of still another book worth writing, Being and Novelty, showing how the creation of novelty and value is essential to human (and divine) existence. One of Davis' key arguments is that experience, thus understood, includes mental and axiological (value-related) dimensions. It is, to use a marvelous phrase, axionoetic. As Davis well recognizes (along with Faber) Whitehead can help us better understand axionoeticism. Whitehead speaks of experience as having a physical pole (experience in the mode of causal efficacy) and also a mental pole that is guided, by internally felt aims and values of one sort or another. Wherever there is actuality there is experience, and wherever there is experience there is something like mind and value creation.

For Davis as for Whitehead, axionoeticism is true of human existence and also animal existence, plant existence, cellular existence, microbial existence, quantum existence, and, I might add, should actualities exist in other planes, angelic and demonic, spirit and ancestral existence. Davis’ perspective is cosmic and not merely humanistic. He stands in a long line of philosophical writers who see humans as part of, and included within, a larger cosmic whole – indeed, as he would add, an larger cosmic adventure.

To Cling or Not to Cling

Mind, Value, and Cosmos is more than a parlor game aimed at giving people clarity while enjoying a glass of wine. It is a philosophical invitation into a certain way of experiencing the world that is mindful of mind and value, mindful of God, mindful of the reality of possibilities as well as actualities, mindful of suffering, and mindful of the ultimacy of relationality. What might it be like, existentially, to be mindful of the ultimacy of relationality?

One thing for sure. It would not involve a collapse or neglect of differences: of ways that actual entities and, for that matter, pure possibilities, transcend one another in their uniqueness. Davis emphasizes that the mutual immanence of things is also a mutual transcendence. Yes, actualities are immanent within one another; and, yes again, they are transcendent of one another. Relationality per se includes immanence and transcendence: mutual interfusion but also mutual difference. The jewels in Indra's net remain unique even as they reflect one another. No two jewels are identical.

Consider, for example, our minds and our bodies. They are immanent within one another, in that our minds affect our bodies and our bodies affect our minds. And yet they are mutually transcendent in that our bodies have powers that transcend our mental purposes and our mental purposes, likewise have powers that transcend our bodies. And so it is, says Davis, with God and the world. They are mutually immanent and mutually transcendent. Mutually immanent and mutually unique.

The Buddhist phrase for uniqueness is suchness or the as-it-isness of each thing in its particularity, Buddhists tell us that when we are aware of the ultimacy of relationality, we do not cling to things, actual or potential, as if they could exist all by themselves. We carry within our hearts and minds a lightness that knows the sheer interconnectedness of things.

Davis’ book does not lean in this non-clinging direction. He seems more interested in how, if we believe in God, we might nevertheless live passionately, finding value and beauty in the world and realizing our own potentials for creativity and connection. He seems to be reacting to traditions in Western theology that were so God-focused that they neglected worldly value. One of his primary aims in Mind, Value, and Cosmos is God affirmation and World affirmation, neither to the exclusion of the other.

Ultimacy and the Religions

Even as Mind, Value, and Cosmos is written primarily for philosophers and philosophical theologians, it can also enrich those who, like me, teach the world's religions, especially if the word “ultimate” is used to name an idea around which a given world religion is centered.

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, for example, center themselves around the ultimacy of a supreme mind from whose will and creativity the universe comes into existence, and who seeks to guide living beings toward goodness and truth and beauty. Advaita Vedanta Hinduism centers itself around a creative and formless abyss, beyond good and evil, that is expressed in all things but reducible to none of them. It does not “call” a person; rather a person “awakens” to it. Confucianism centers itself around Heaven, to be sure, but more deeply around harmonious relations among human beings in community with one another and with the earth. Zen Buddhism centers itself around the ‘ultimacy’ of the present moment, as it gathers together the entire unity in the evanescent aliveness of the here-and-now. Each of these four ‘centers’ makes sense from a Whiteheadian point of view. There is something ultimate about the cosmic Mind, something ultimate about the Creative Abyss, something ultimate about the harmony of community and something ultimate about the present moment. Someone might argue that these different centers are really the same center and all part of a single ultimate, but it seems more honest and respectful simply to acknowledge that they may well be different ultimates to which people in different cultural and religious traditions have oriented their lives: each ‘real’ in its own way.

Pure Formless Activity

As you read Davis' book it is easy to see where three of the centers lie: the God of Abrahamic faiths, the harmony in society of Confucianism, and the present moment of Zen. But what of the creative and formless abyss of, say Advaita Vedanta Hinduism, which in western traditions is sometimes called the Godhead. The parallel in Davis would be Whitehead's understanding of Creativity, that ultimate reality of which all things -- good and evil, happy and sad, violent and peaceful, just and unjust, alive or asleep, safe or threatened, truthful or dishonest - are expressions. Of Creativity in Whitehead Davis writes:

Whitehead holds that the word “Creativity” nicely expresses “the notion that each event is a process issuing in novelty”—what Whitehead calls a “concrescence.” Indeed the phrase “Immanent Creativity,” or “Self-Creativity,” he states, “avoids the implication of a transcendent Creator.”… Creativity, for Whitehead, is not something that can be “created”—even for God—since it is a presupposition of any and all creative activity, be it finite or divine. In fact, it is not “something” at all, but pure formless activity embodied in all actuality—and chiefly so in divine Actuality.

In Whitehead’s philosophy this pure formless activity is embodied in each and every moment of experience as its innermost act of ‘decision.’ Decision is the act of cutting off certain possibilities for responding to what is given and thereby actualizing other possibilities. The act itself does not derive from the past or the future or from God. It arises out of nothing in the present moment: that is, out of the creative abyss of Creativity.

Whereas Davis emphasizes the value that is created by this decision; those of us with a Zen mind might like also to emphasize the act of decision itself, the cutting off. It is an act of pure spontaneity that is, says Whitehead, the very essence of actuality. To the question Why is there something rather than nothing? the answer is self-creative spontaneity. And to the question Where does it come from? The answer is, in a deep and almost mystical sense, now-here. It is the ultimacy of each present moment, on its own terms and for its own sake, as deciding itself into existence in relation to the World and God.

God and Fire

Interestingly, for Davis as for Whitehead, God, too, embodies this self-creative spontaneity. Davis is especially interested in how God embodies or expresses spontaneity in a loving, value-centered, wise, and caring way that is, for him, the ultimate and most inclusive form of Creativity. Indeed, Davis speaks of self-creative spontaneity as embodied chiefly (his word) in divine Actuality, but then adds that God requires the world to do this, not unlike the way any moment of human experience requires a world in order to create itself.

… for God does not unilaterally produce actuality as such, but is rather the poet of actuality, inaugurating the creative firing of finitude through the provision of divine aims, such that events can actually create themselves. In a deep sense then, God primordially requires the co-creative actuality of the World process for the real achievement of Value—thereby endowing a grandeur upon the World. So too the World process requires God primordially for its possibility and axiological aim. In this way, God and the world are indivisible co-laborers on behalf of the creation of value.

This, I believe, is one of most important invitations we receive from Davis in Mind, Value, and Cosmos. It is invitation to orient our lives in ways that are inwardly responsive to a universal Poet -- everywhere at once -- who can be imagined in many different ways, and who is experienced both as an eternal companion to the world's joys and sufferings and also an inwardly felt lure toward truth, goodness and beauty. A Poet whose very "standpoint" is everywhere at once and whose region includes all regions. A Poet who beckons us to join the great work (the labor) of creating communities that are just, sustainable, and joyful, awakened to the value of the more than human world, to the animals and plants and hills and rivers, who are our teachers, too. A Poet who needs us as much as we need her or him, because we are together even as we are distinct, depending one one another for our very existence. A Poet whom, if we wish, we can imagine as many Poets, forever changing shape relevant to the situation at hand. A Poet in whose embrace we forever dwell, even in moments of forgetfulness, that is as palpable in its way - a creative firing -- as is the embrace of a lover, or a mother, or a friend. Mind, Value, and Cosmos is an invitation to feel the fire of God and to become fire ourselves, as best we can, moment by moment.

Is this Poet all-powerful? Well, not exactly. The Poet is likewise in the grip of Creativity. There will be forms of novelty that are painful to us and to the poet. But the Poet is steadfast in love and fidelity, almost as if she or he has made a covenant with us, never to abandon us, and to hold in her heart our memories, even as we might forget them, such that each here-and-now moment is itself carried forever in her ongoing life. With this trust perhaps we, too, can let go, or not cling, to the values we create and are. Although Davis emphasizes passion rather than not-clinging, I find myself wondering, hoping, that the two might be united in a rather deep awakening, a deep relational insight, that holds the truth of perpetual perishing and that of creative novelty in a single open hand, welcoming fire while cooled by water, both divine. By water I mean the peace that surpasses all understanding, because awakened to the ultimately of relationality itself, a Harmony of Harmonies that includes the whole and is, says Whitehead, another name for God. Not just a jewel of gems but also, in a way, the net of gems itself, somehow laced with one last form of connection: divine love.

Is this too much to ask? Such are the questions with which Davis leaves me. And isn't this part of his point? Isn't it that, as we work through his ideas, we, too, become questers?

- Jay McDaniel

Addendum

Getting to know Andrew Davis' outlook on life

from poems on his website

"God"