WHAT IS PROCESSUAL PRIMORDIAL TIME

before the Big Bang?

by R.E. Slater

January 24, 2022

As Intro, please refer to my more recent post on God and Time here:

Until recently, asking what happened before the Big Bang was generally considered by physicists to be a religious question. General Relativity Theory just does not go there. As time goes to zero, General Relativity spews out zeros and infinities. So the question did not make sense from a mathematical/scientific point of view. - Anon

"The initial singularity [before the Big Bang] is a singularity predicted by some models of the Big Bang theory to have existed before the Big Bang and thought to have contained all the energy and spacetime of the Universe. The instant immediately following the initial singularity is part of the Planck epoch, the earliest period of time in the history of our universe." - Wikipedia

In scientific terminology the Cosmological Principle is the idea that the universe is "everywhere homogeneous and isotropic". Homogeneous means uniform or evenly distributed. Isotropic means it looks the same in all directions, i.e. there are no large clumps or voids in any direction. - Anon

To the question, "What is time?" I would like to respond as perhaps a process theologian might on the topic using the language of physics and poetic metaphor where in both senses imagination breaks down into wordless space...

Process-based Quantum Implications

Process Thought would define "time" as a series of relational events utilizing Whiteheadian process philosophy and theology, named for Alfred North Whitehead, the British mathematician and philosopher of the British Royal Academy during Einstein's time.

At the quantum level, if there were no relational movement, or interaction, in force or energy, then there could be no time.

As example, before the occurrence of the big bang in the universe (sic, before the Planck Era) one could describe the singularity of this primordial era to have a consistency of an homogenous one-dimensional (1D) infinitely hot plasmic space without distinguishment within itself. Time would not be present because time is dependent upon matter interacting with itself. In this space time could not.

Within this kind of a primordial universe there were no matter elements acting upon one another. In fact, space was so condensed in upon itself there could be no "space" as well... just a plasmic soup of infinite density. Hence, to use the mere terms of "space" and "time" would be lost to our vocabulary as timeful beings living within the spacetime continuum of our present cosmos. They are words without meaning in this state of infinitely dense singularity.

One might further describe this "space" as a static plasmic state of null-reactions as opposed to a dynamic hot plasmic state showing movement or irregularity within itself. That is, there could be no timeful existence in a primordial null-void singularity as there were zero interacting relationships between its infinitely dense substance. Time could not be present in this null-void space of seemingly endless or "infinite" white space. The concept of time could have no meaning at all even as the word "infinity" could have no meaning.

And since matter held no irregularities within this primordial null-void substance of timeless, infinitely dense space, the concept of "spacetime" could not exist either. Nor could this primordial singularity be described as either closed or open, as even these descriptors would be inadequate to its cosmology. All would seem infinitely near or infinitely distant in a null-void, zero-time singularity without quantum edge or boundary. Hence, primordial matter would be indistinguishable from itself and completely homogenous through-and-through-and-through its material substance.

Lastly, once quantum irregularity was somehow introduced into its singularly homogenous, non-structured (or un-structure) substance in the form of heat, frequency, pressure, density, etc, then in that instant did space transform and begin to define itself, while in that same instance did timeful interactions result. The resulting characteristic of the infamous Planck Era would be one of cosmic relationship between space and time; between evolving matter with itself; something we now casually describe as spacetime. More specifically, this would be a relational spacetime structure consisting of a never ending series of interacting - or, processually interactive - events initiating the first state of a never-ending creational cosmological evolution where we may now speak of a "stellar void" filled with self-annihilating matter/antimatter moments rather than a "null-void" substance of non-existent relationships.

Process-based Theological Implications

By inference, the idea of Cosmic Relationality defines all we know as a time-filled - or better, time-informed - relational cosmology. Wherever we look a relationship exists between matter (elements, forces, energies, etc). Moreover, the idea of a processual evolution may further inform a process-based relational cosmology: one that moves forward together both processually and relationally eliciting unique interactive future moments of possibility and wonder. Thus the Whiteheadian word for "cosmic feeling all-the-way down" into the very substance of the cosmos. Which was also why Whitehead described Process Philosophy first as a "Philosophy of Organism". One that was living, connected, and interactive with itself. Especially a cosmology beheld in valuative terms of wellbeing filled with possibility, describing its character and future (hope).

Referring back to the idea of an evolving cosmology consisting of a kind of "cosmic feeling" all the way down. This means that humanity is not alone, or unique, in itself - but bears upwards on an evolutionary scale a deep fundamental "feeling," comportment, attachment, or affiliation, with the structure of the cosmic elements themselves already present in the universe itself. And where did this ultimate source of processual relationality come from? For the Christian, as well as for many spiritual religions, this quality came from God's Self.

One may therefore describe the cosmos as a derivative of God's Processual-Relational Essence or Being. This then is what is meant by a Christian theology described as a Relational Process Theology - a quality of theology which may also be found in other religions and faiths when the idea of "theology" is applied both positively and pervasively. All religions, like nature itself, operate best when operating within a relational sphere of influential fellowship.

Further, we should also note that a Processual Relational Theology is a derivative of a Processual Relational Philosophy where the former builds upon the latter in a specific direction: in this case, upon a religious "faith or belief" with its derivative constructs of socio-politico religion. A good faith is one which i) connects with the universe, ii) connects with nature, iii) connects with one another, and iv) connects with God. A faith which shows valuative movement of wellbeing, healing, and love. Process Theology is such a philosophy.

Moreover, a relational process theology may also go hand-in-hand with the Christian idea of "creatio continua"... creation from something that is already there but unformed. A primordial creation which exists without any kind of defined relationship between things. (By the way, the term creation may be considered an inexact term in that the existent primordial matter wasn't so much "created" as it was simply "there, but unformed". That is, without any meaningful relationships within or without itself, though such terms would be meaningless as mentioned above in the opening paragraphs.)

Time therefore is a result of an event and not a thing in itself. That is, time is not a substance, but an event. It is a result of the processual interaction of dimensional quantum harmonics, frequencies, strings, or loopy gravitational forces and energies working in relationship with-and-against each other. Time is ultimately a relational event. If there is no time then there are no eventful relations.

One last, to reiterate a previous point, if a primordial cosmos was already there then it wasn't so much "created" as given a relational presence to itself by either (i) divine fiat or (ii) by absorbing God's relational being via mere association with the Divine. An association permeating with open-ended indeterminancy and processual futures as previous accumulating pasts (prehensions) interact with coinciding presents (actualities) where each prehension and actuality, together, propel newly initiating dynamics of actualizing possibilities of future import. This is the import of process philosophy which process theology then builds upon.

Thus and thus, the future is as hopeful as it is chaotic. Moreover, a process theology will also insist on a future whose character is one that is valuative and bearing wellbeing for all entities involved and interacting with one another. If it were not so, an entropic cosmos in the heavens or on earth could not have evolved as a processual evolutionary series of events within a cosmic creation described as a processual relationship of organism.

R.E. Slater

January 24, 2022

revised, January 26, 2022

*Should a reader discover additional process-related articles on the subject of "what is time", please forward to me those links in the comments section. Thanks!

QUANTUM TIMELINE OF THE BIG BANG

Since the Big Bang, 13.7 billion years ago, the universe has passed through many different phases or epochs. Due to the extreme conditions and the violence of its very early stages, it arguably saw more activity and change during the first second than in all the billions of years since.

From our current understanding of how the Big Bang might have progressed, taking into account theories about inflation, Grand Unification, etc, we can put together an approximate timeline as follows:

Planck Epoch (or Planck Era), from zero to approximately 10-43 seconds (1 Planck Time):

This is the closest that current physics can get to the absolute beginning of time, and very little can be known about this period. General relativity proposes a gravitational singularity before this time (although even that may break down due to quantum effects), and it is hypothesized that the four fundamental forces (electromagnetism, weak nuclear force, strong nuclear force and gravity) all have the same strength, and are possibly even unified into one fundamental force, held together by a perfect symmetry which some have likened to a sharpened pencil standing on its point (i.e. too symmetrical to last). At this point, the universe spans a region of only 10-35 meters (1 Planck Length), and has a temperature of over 1032°C (the Planck Temperature).

Grand Unification Epoch, from 10–43 seconds to 10–36 seconds:

The force of gravity separates from the other fundamental forces (which remain unified), and the earliest elementary particles (and antiparticles) begin to be created.

Inflationary Epoch, from 10–36 seconds to 10–32 seconds:

Triggered by the separation of the strong nuclear force, the universe undergoes an extremely rapid exponential expansion, known as cosmic inflation. The linear dimensions of the early universe increases during this period of a tiny fraction of a second by a factor of at least 1026 to around 10 centimeters (about the size of a grapefruit). The elementary particles remaining from the Grand Unification Epoch (a hot, dense quark-gluon plasma, sometimes known as “quark soup”) become distributed very thinly across the universe.

Electroweak Epoch, from 10–36 seconds to 10–12 seconds:

As the strong nuclear force separates from the other two, particle interactions create large numbers of exotic particles, including W and Z bosons and Higgs bosons (the Higgs field slows particles down and confers mass on them, allowing a universe made entirely out of radiation to support things that have mass).

Quark Epoch, from 10–12 seconds to 10–6 seconds:

Quarks, electrons and neutrinos form in large numbers as the universe cools off to below 10 quadrillion degrees, and the four fundamental forces assume their present forms. Quarks and antiquarks annihilate each other upon contact, but, in a process known as baryogenesis, a surplus of quarks (about one for every billion pairs) survives, which will ultimately combine to form matter.

Hadron Epoch, from 10–6 seconds to 1 second:

The temperature of the universe cools to about a trillion degrees, cool enough to allow quarks to combine to form hadrons (like protons and neutrons). Electrons colliding with protons in the extreme conditions of the Hadron Epoch fuse to form neutrons and give off massless neutrinos, which continue to travel freely through space today, at or near to the speed of light. Some neutrons and neutrinos re-combine into new proton-electron pairs. The only rules governing all this apparently random combining and re-combining are that the overall charge and energy (including mass-energy) be conserved.

Lepton Epoch, from 1 second to 3 minutes:

After the majority (but not all) of hadrons and antihadrons annihilate each other at the end of the Hadron Epoch, leptons (such as electrons) and antileptons (such as positrons) dominate the mass of the universe. As electrons and positrons collide and annihilate each other, energy in the form of photons is freed up, and colliding photons in turn create more electron-positron pairs.

Nucleosynthesis, from 3 minutes to 20 minutes:

The temperature of the universe falls to the point (about a billion degrees) where atomic nuclei can begin to form as protons and neutrons combine through nuclear fusion to form the nuclei of the simple elements of hydrogen, helium and lithium. After about 20 minutes, the temperature and density of the universe has fallen to the point where nuclear fusion cannot continue.

Photon Epoch (or Radiation Domination), from 3 minutes to 240,000 years:

During this long period of gradual cooling, the universe is filled with plasma, a hot, opaque soup of atomic nuclei and electrons. After most of the leptons and antileptons had annihilated each other at the end of the Lepton Epoch, the energy of the universe is dominated by photons, which continue to interact frequently with the charged protons, electrons and nuclei.

Recombination/Decoupling, from 240,000 to 300,000 years:

As the temperature of the universe falls to around 3,000 degrees (about the same heat as the surface of the Sun) and its density also continues to fall, ionized hydrogen and helium atoms capture electrons (known as “recombination”), thus neutralizing their electric charge. With the electrons now bound to atoms, the universe finally becomes transparent to light, making this the earliest epoch observable today. It also releases the photons in the universe which have up till this time been interacting with electrons and protons in an opaque photon-baryon fluid (known as “decoupling”), and these photons (the same ones we see in today’s cosmic background radiation) can now travel freely. By the end of this period, the universe consists of a fog of about 75% hydrogen and 25% helium, with just traces of lithium.

Dark Age (or Dark Era), from 300,000 to 150 million years:

The period after the formation of the first atoms and before the first stars is sometimes referred to as the Dark Age. Although photons exist, the universe at this time is literally dark, with no stars having formed to give off light. With only very diffuse matter remaining, activity in the universe has tailed off dramatically, with very low energy levels and very large time scales. Little of note happens during this period, and the universe is dominated by mysterious “dark matter”.

Reionization, 150 million to 1 billion years:

The first quasars form from gravitational collapse, and the intense radiation they emit reionizes the surrounding universe, the second of two major phase changes of hydrogen gas in the universe (the first being the Recombination period). From this point on, most of the universe goes from being neutral back to being composed of ionized plasma.

Star and Galaxy Formation, 300 - 500 million years onwards:

Gravity amplifies slight irregularities in the density of the primordial gas and pockets of gas become more and more dense, even as the universe continues to expand rapidly. These small, dense clouds of cosmic gas start to collapse under their own gravity, becoming hot enough to trigger nuclear fusion reactions between hydrogen atoms, creating the very first stars.

The first stars are short-lived supermassive stars, a hundred or so times the mass of our Sun, known as Population III (or “metal-free”) stars. Eventually Population II and then Population I stars also begin to form from the material from previous rounds of star-making. Larger stars burn out quickly and explode in massive supernova events, their ashes going to form subsequent generations of stars. Large volumes of matter collapse to form galaxies and gravitational attraction pulls galaxies towards each other to form groups, clusters and superclusters.

Solar System Formation, 8.5 - 9 billion years:

Our Sun is a late-generation star, incorporating the debris from many generations of earlier stars, and it and the Solar System around it form roughly 4.5 to 5 billion years ago (8.5 to 9 billion years after the Big Bang).

Today, 13.7 billion years:

The expansion of the universe and recycling of star materials into new stars continues.

Chronology of the Universe in five stages

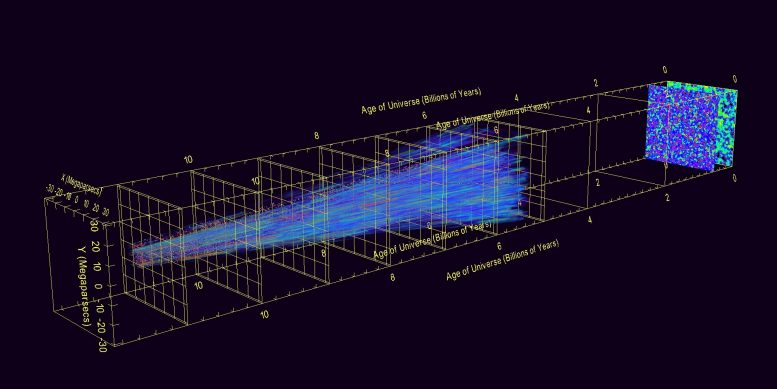

Diagram of evolution of the (observable part) of the universe from the Big Bang (left), the CMB-reference afterglow, to the present.

For the purposes of this summary, it is convenient to divide the chronology of the universe since it originated, into five parts. It is generally considered meaningless or unclear whether time existed before this chronology:

The very early universe

The first picosecond (10−12) of cosmic time. It includes the Planck epoch, during which currently established laws of physics may not apply; the emergence in stages of the four known fundamental interactions or forces—first gravitation, and later the electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions; and the expansion of space itself and supercooling of the still immensely hot universe due to cosmic inflation.

Tiny ripples in the universe at this stage are believed to be the basis of large-scale structures that formed much later. Different stages of the very early universe are understood to different extents. The earlier parts are beyond the grasp of practical experiments in particle physics but can be explored through other means.

The early universe

This period lasted around 370,000 years. Initially, various kinds of subatomic particles are formed in stages. These particles include almost equal amounts of matter and antimatter, so most of it quickly annihilates, leaving a small excess of matter in the universe.

At about one second, neutrinos decouple; these neutrinos form the cosmic neutrino background (CνB). If primordial black holes exist, they are also formed at about one second of cosmic time. Composite subatomic particles emerge—including protons and neutrons—and from about 2 minutes, conditions are suitable for nucleosynthesis: around 25% of the protons and all the neutrons fuse into heavier elements, initially deuterium which itself quickly fuses into mainly helium-4.

By 20 minutes, the universe is no longer hot enough for nuclear fusion, but far too hot for neutral atoms to exist or photons to travel far. It is therefore an opaque plasma.

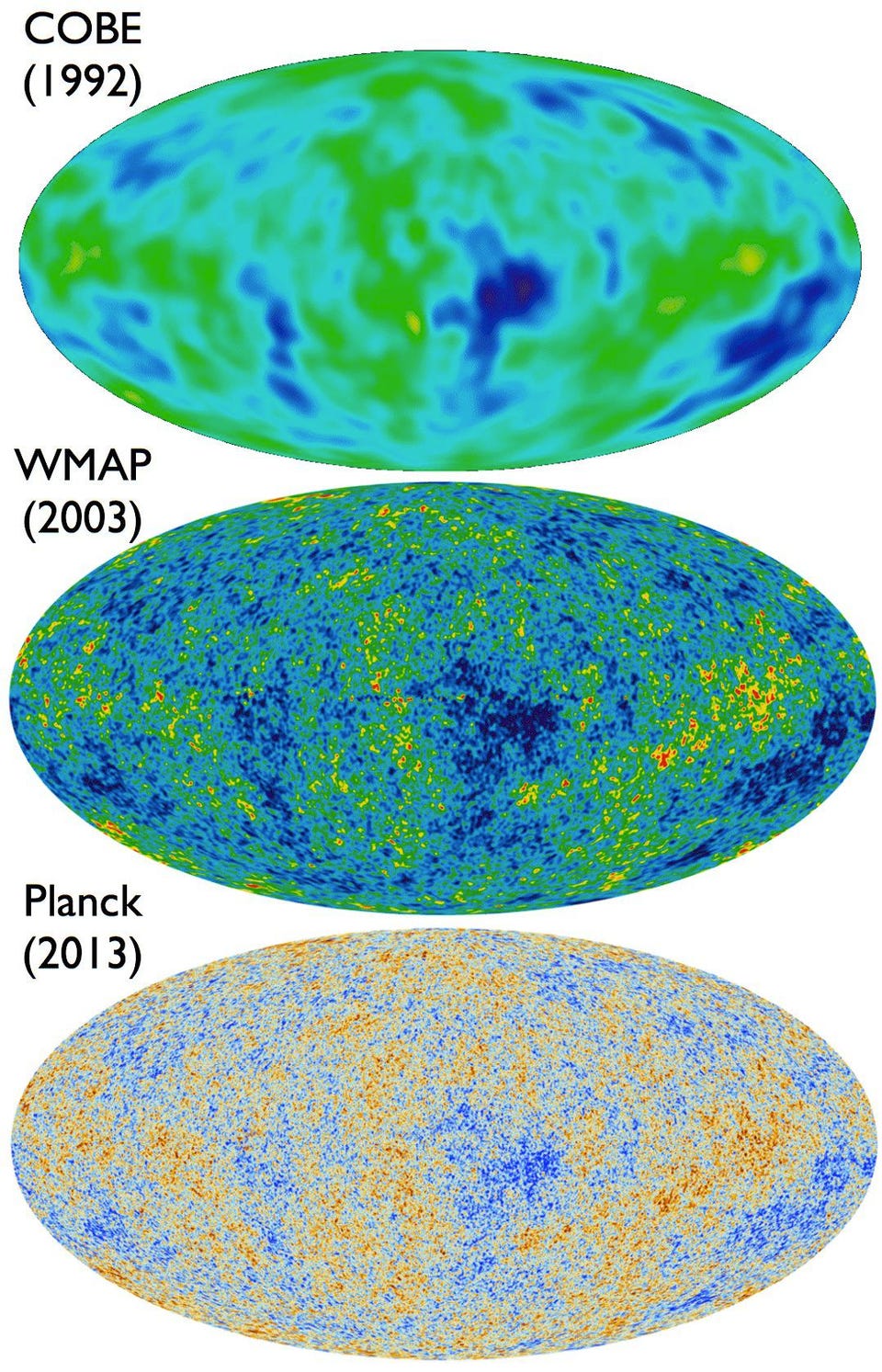

The recombination epoch begins at around 18,000 years, as electrons are combining with helium nuclei to form He+. At around 47,000 years,[2] as the universe cools, its behavior begins to be dominated by matter rather than radiation. At around 100,000 years, after the neutral helium atoms form, helium hydride is the first molecule. (Much later, hydrogen and helium hydride react to form molecular hydrogen (H2) the fuel needed for the first stars.) At about 370,000 years,[3] neutral hydrogen atoms finish forming ("recombination"), and as a result the universe also became transparent for the first time. The newly formed atoms—mainly hydrogen and helium with traces of lithium—quickly reach their lowest energy state (ground state) by releasing photons ("photon decoupling"), and these photons can still be detected today as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). This is the oldest observation we currently have of the universe.

The Dark Ages and large-scale structure emergence

From 370,000 years until about 1 billion years. After recombination and decoupling, the universe was transparent but the clouds of hydrogen only collapsed very slowly to form stars and galaxies, so there were no new sources of light. The only photons (electromagnetic radiation, or "light") in the universe were those released during decoupling (visible today as the cosmic microwave background) and 21 cm radio emissions occasionally emitted by hydrogen atoms. The decoupled photons would have filled the universe with a brilliant pale orange glow at first, gradually redshifting to non-visible wavelengths after about 3 million years, leaving it without visible light.

The cosmic Dark Ages

At some point around 200 to 500 million years, the earliest generations of stars and galaxies form (exact timings are still being researched), and early large structures gradually emerge, drawn to the foam-like dark matter filaments which have already begun to draw together throughout the universe. The earliest generations of stars have not yet been observed astronomically. They may have been huge (100–300 solar masses) and non-metallic, with very short lifetimes compared to most stars we see today, so they commonly finish burning their hydrogen fuel and explode as highly energetic pair-instability supernovae after mere millions of years.[4] Other theories suggest that they may have included small stars, some perhaps still burning today. In either case, these early generations of supernovae created most of the everyday elements we see around us today, and seeded the universe with them.

Galaxy clusters and superclusters emerge over time. At some point, high-energy photons from the earliest stars, dwarf galaxies and perhaps quasars leads to a period of reionization that commences gradually between about 250–500 million years, is complete by about 700–900 million years, and diminishes by about 1 billion years (exact timings still being researched). The universe gradually transitioned into the universe we see around us today, and the Dark Ages only fully came to an end at about 1 billion years.

While early stars have not been observed, some galaxies have been observed from about 400 million years cosmic time (GN-z11 at redshift z≈11.1, just after the start of reionization); these are currently our early observations of stars and galaxies. The James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021, is intended to push this back to z≈20 (180 million years cosmic time), enough to see the first galaxies (≈270 my) and early stars (≈100 to 180 my).

The universe as it appears today

From 1 billion years, and for about 12.8 billion years, the universe has looked much as it does today and it will continue to appear very similar for many billions of years into the future. The thin disk of our galaxy began to form at about 5 billion years (8.8 Gya),[5] and the Solar System formed at about 9.2 billion years (4.6 Gya), with the earliest traces of life on Earth emerging by about 10.3 billion years (3.5 Gya).

The thinning of matter over time reduces the ability of gravity to decelerate the expansion of the universe; in contrast, dark energy (believed to be a constant scalar field throughout our universe) is a constant factor tending to accelerate the expansion of the universe. The universe's expansion passed an inflection point about five or six billion years ago, when the universe entered the modern "dark-energy-dominated era" where the universe's expansion is now accelerating rather than decelerating. The present-day universe is understood quite well, but beyond about 100 billion years of cosmic time (about 86 billion years in the future), uncertainties in current knowledge mean that we are less sure which path our universe will take.

The far future and ultimate fate

At some time the Stelliferous Era will end as stars are no longer being born, and the expansion of the universe will mean that the observable universe becomes limited to local galaxies. There are various scenarios for the far future and ultimate fate of the universe. More exact knowledge of our current universe will allow these to be better understood.

* * * * * * *

Bang, Bounce or Something Else?

Time began at the Big Bang — or did it? Alternative ideas, including a universe

that repeatedly reboots itself, suggest something came before the Big Bang.

April 22, 2020

One thing that makes cosmology fun is how much you can notice from simple observations. Why, for example, is the night sky so uniform? If you look in opposite directions to the farthest reach of your vision, the universe looks pretty much the same, yet those distant places have never communicated with each other. They are too far apart. Light from each side of the sky is only now reaching us in the middle, so it hasn’t had time to cross to the other side yet, and no physical process links the two. So why do they look so alike?

That uniformity is a glimpse of a cosmic prehistory. For 13.8 billion years, the universe has been expanding, cooling and evolving. Textbooks often say that the start of this expansion — the Big Bang — was the start of time. But if so, those widely separated regions could never have attained the same temperature and density, and other basic features of the universe would likewise seem inexplicable. “That’s all related to your assumption that there was a beginning of time, so why don’t you give up on that beginning-of-time idea?” says Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University. “That was a simple extrapolation of Einstein’s equations, assuming no change even when you get to energies and temperatures that have never been probed before.”

Most cosmologists think that something must have set the stage for the expansion we observe, although they disagree on what. Steinhardt was a co-author of the standard account — cosmic inflation — but has since turned against it and now promotes a competing model in which our universe is the latest round in a perpetual cycle of creation and destruction. Other scientists, too, are exploring alternatives to standard inflationary theory — and to Einstein’s gravity theory — to fill in the prehistory. “Some alternatives try to provide a pre-inflationary phase,” says Greg Gabadadze of New York University, who is associate director for physics in the foundation’s Mathematics and Physical Sciences division. “Others don’t use the inflationary mechanism but still have a phase which is before the Big Bang — before the conventional expanding phase.”

Cosmologists might finally be approaching some closure on this question. The Simons Observatory, a ground-based array of telescopes designed to make definitive measurements of the cosmic microwave background, is scheduled to see first light in 2020 and reach the requisite sensitivity in five years. Among other things, it will search for gravitational waves from the prehistorical cosmic period, which some models predict and others do not. “Both cases will be interesting: discovery or nondiscovery,” Gabadadze says.

|

Evolution of the Universe from the Big Bang on the left to the modern universe on the right. | Credit: NASA |

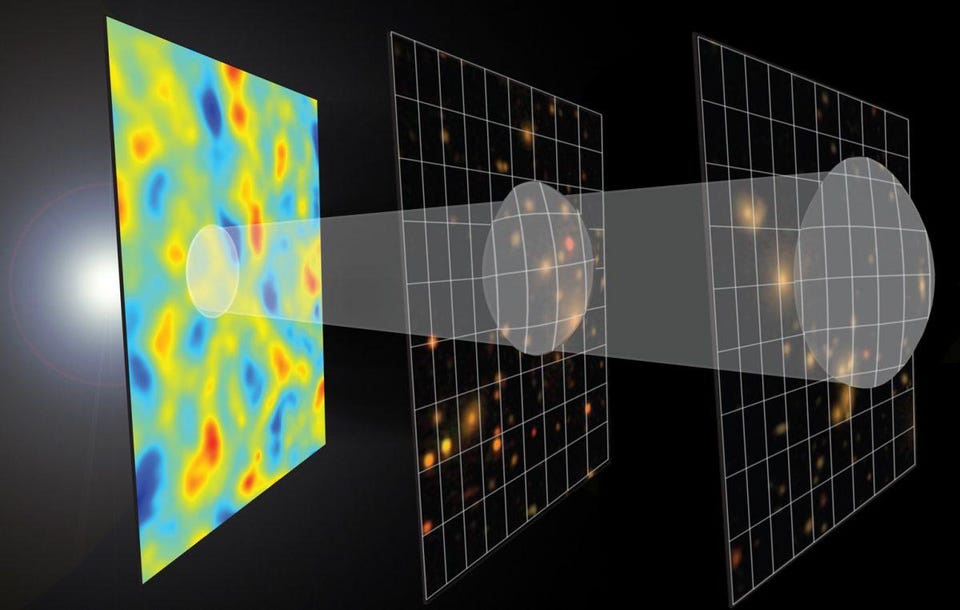

What makes the expansion of the universe tricky to think about is that ‘the’ universe is not the same as our universe. We see only part of the whole, limited by how far light has been able to travel since space began stretching — a distance known as the cosmological horizon. In the standard Big Bang picture, not only does space get bigger, but we see ever more of it. “The rate of stretching is slower than the rate of light propagation through space, so we can receive light from more and more distant sources,” explains Anna Ijjas of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics.

The ideas for a cosmic prehistory say that one or both of these rates used to differ from what they are now. During cosmic inflation, for example, space expanded at a quickening pace, while the cosmological horizon stayed fixed. An observer during this period would see ever less of space. “It’s the relative growth of space compared to the horizon that’s the important thing,” Steinhardt says. The horizon also limits the range over which physical processes can operate. At first, two nearby regions were able to exchange material and even themselves out. Then space pulled them apart until they exited each other’s horizons, at which point they fell out of touch. Some time later, inflation ended, ushering in the present epoch. Distant regions are uniform because they used to be close together. Similarly, the universe appears to be geometrically flat because the broad curvature of space, if it had curvature, was lost to view.

Steinhardt and Ijjas argue that space need not have grown at all to achieve this effect; on the contrary, it could have shrunk. Cosmologists have toyed with contracting models before, supposing that the universe will reach some peak size, collapse under its own weight back to a pinprick, and bounce to begin a new cycle of expansion and contraction. But those models did not seek to account for cosmic uniformity and flatness. In Steinhardt and Ijjas’ scenario, these attributes are the result of the contracting phase of the preceding cycle.

Moreover, they argue that space need not collapse by all that much before bouncing. Instead it is the cosmological horizon that shrinks to almost nothing. In this scenario, the horizon is defined as how far observers can see before the bounce occurs. “The distance that light can propagate before the bounce gets less and less,” Ijjas says. As the horizon closes in on observers, galaxies vanish from sight and a curtain falls on the broad curvature of space. “Space is becoming more curved in the absolute sense, but your horizon is shrinking faster,” Steinhardt says. “You’re seeing less and less of it, so as you approach the contraction, as far as you can see, that patch looks extremely uniform and flat.”

If you could experience this process, you would lose sight of other galaxies, then stars in our own galaxy, then Mars and the moon, then the other side of the room. Soon your own body would cease to operate as a coherent being, and individual particles would live in utter isolation, no longer interacting. The universe would have completely atomized. All its structures would be frozen in place, emerging from hibernation only when the horizon was able to grow again.

A shrinking horizon is a feature of other alternatives to inflation as well. In so-called Galilean genesis, space initially expanded slowly and had no trouble evening itself out. “At the very beginning the horizon has an infinite size and, as the universe evolved in the genesis phase, the horizon size gets smaller,” Gabadadze says. Additional energy fields and nonlinear interactions among those fields seeded space with matter and revved up its expansion, thereby putting the bang into the Big Bang.

All these models have much in common. They require physics beyond present theories: new forms of energy (akin to dark energy) and perhaps modifications to Einsteinian gravity. They require an even earlier epoch — a pre-prehistory — to make the universe uniform and set up the conditions for expansion or contraction. They naturally produce not just one universe but potentially infinitely many, either in the form of a vast effervescence of bubbles (as in inflation) or as an endlessly repeating cycle (as in Steinhardt and Ijjas’ model).

But the models have crucial differences, too. Inflation occurs when the universe is hot and involves high-energy processes, so it is prone to fluctuations that cause it to produce a huge diversity of universes that vary in the distribution of matter and even some aspects of the laws of physics. Thus, space on its vastest scales is highly nonuniform, which is ironic because cosmologists came up with inflation in large part to explain the uniformity of our observed universe. Our universe is, if anything, a rarity. So the theory fails to make firm predictions for what we should see. Proponents of inflation have sought to tinker with the mechanism or supplement the theory with other principles to give it more explanatory power. In contrast, Steinhardt and Ijjas’ cyclic model avoids this problem because its processes occur at comparatively low energy. It produces universes that are broadly similar, with only minor variations from our own.

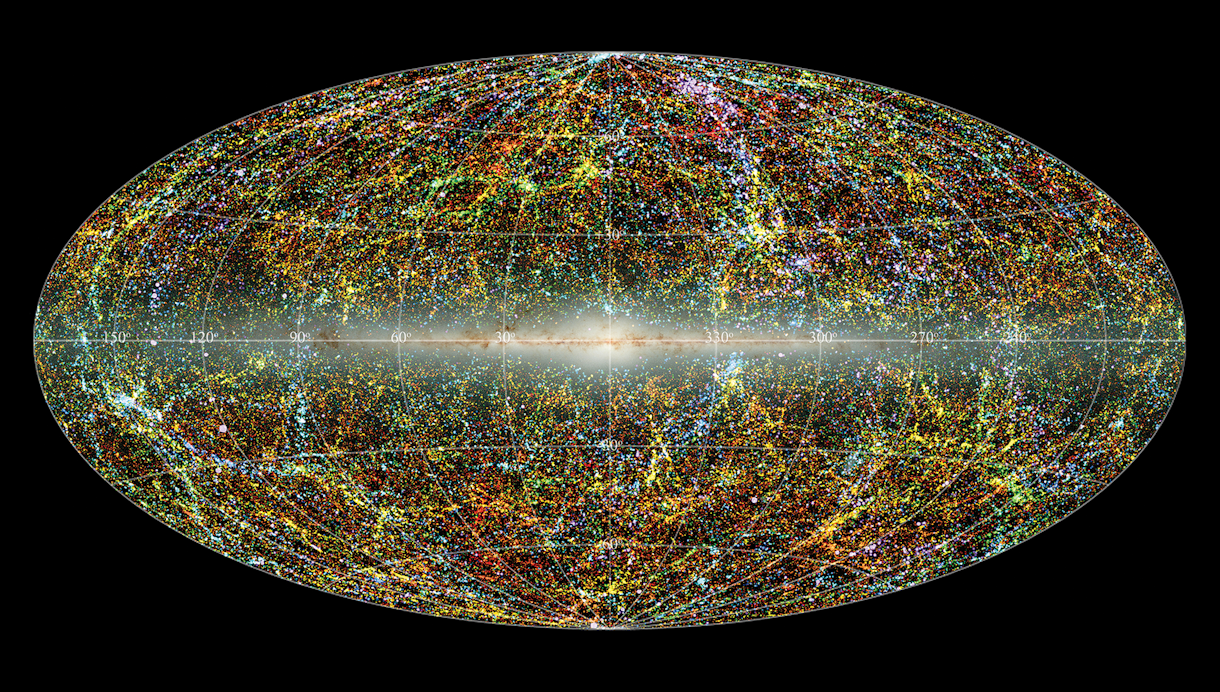

|

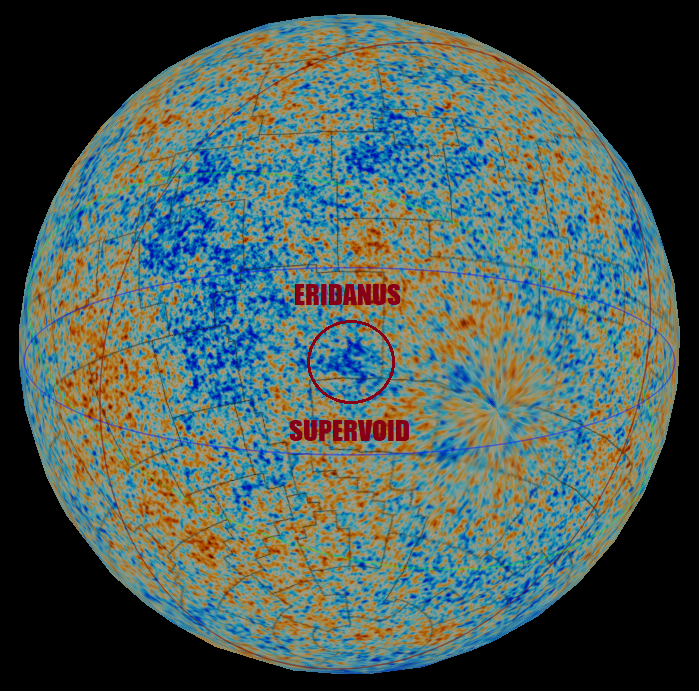

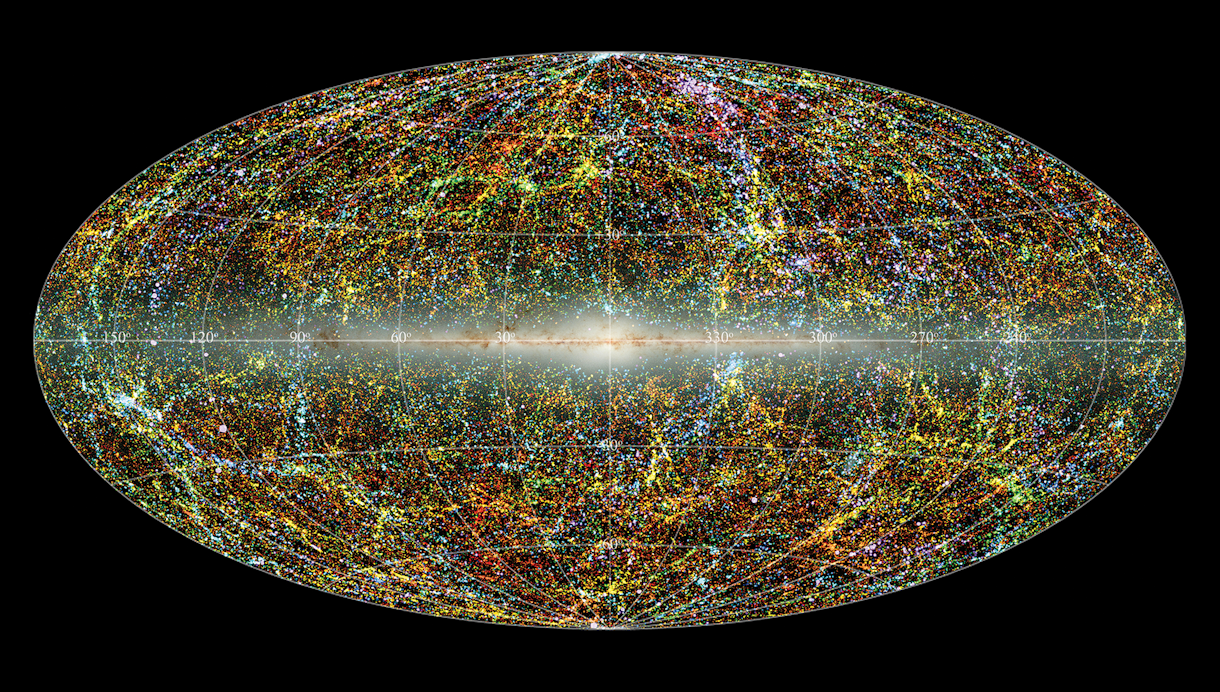

A Universe of Galaxies: This near-infrared map shows the distribution of galaxies around us — those in blue are nearest, those in red are farthest. The bright central band is our Milky Way. The data are derived from the 2MASS Extended Source Catalog of more than 1.5 million galaxies. | Credit: IPAC/Caltech, by Thomas Jarrett |

As with many controversies, both sides make a good case, and the task of deciding between them falls to observers. Inflation would have had conspicuous gravitational side effects because it’s a highly energetic process. “When you produce density fluctuations at high energy, they also produce fluctuations in space-time itself,” Steinhardt says. So far, searches for gravitational waves from this era have come up empty. If the Simons Observatory doesn’t find any either, inflation is in trouble. Are the null results to date already uncomfortable? “Yup, they are,” Gabadadze says. “Already they kind of are.”

Conversely, if the observatory does detect primordial gravitational waves, Steinhardt and Ijjas’ cyclic cosmology is dead. “If we see that, it will disprove many of the competing models,” says Simons Observatory director Brian Keating of the University of California, San Diego.

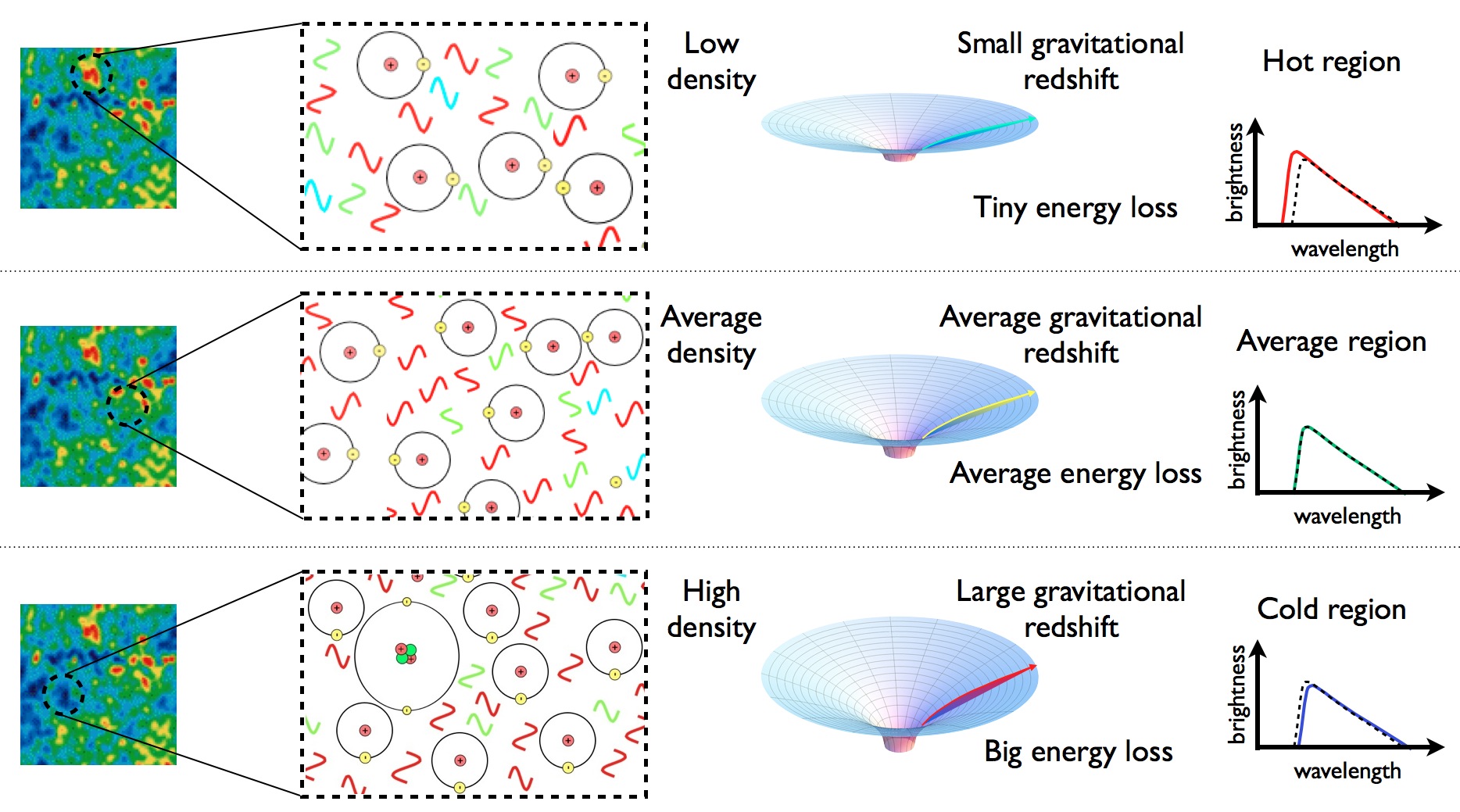

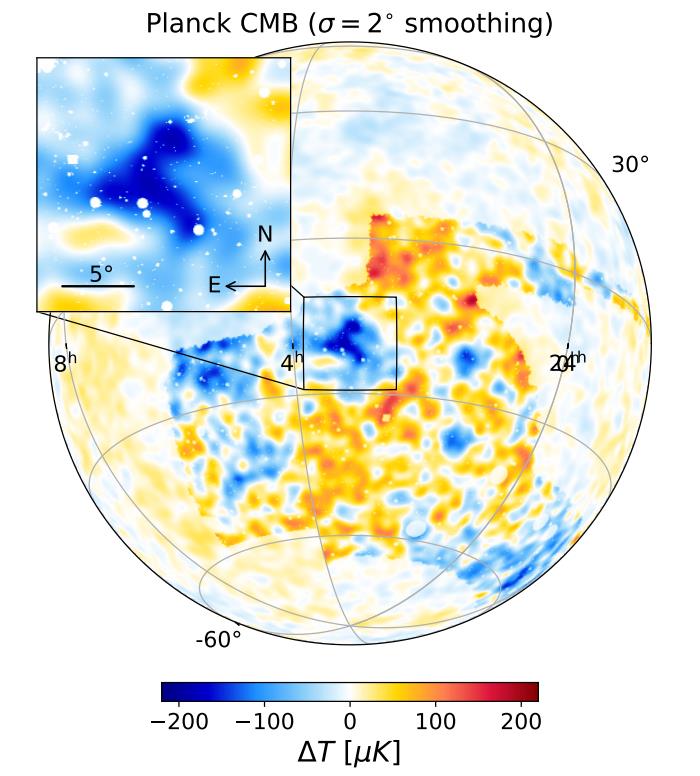

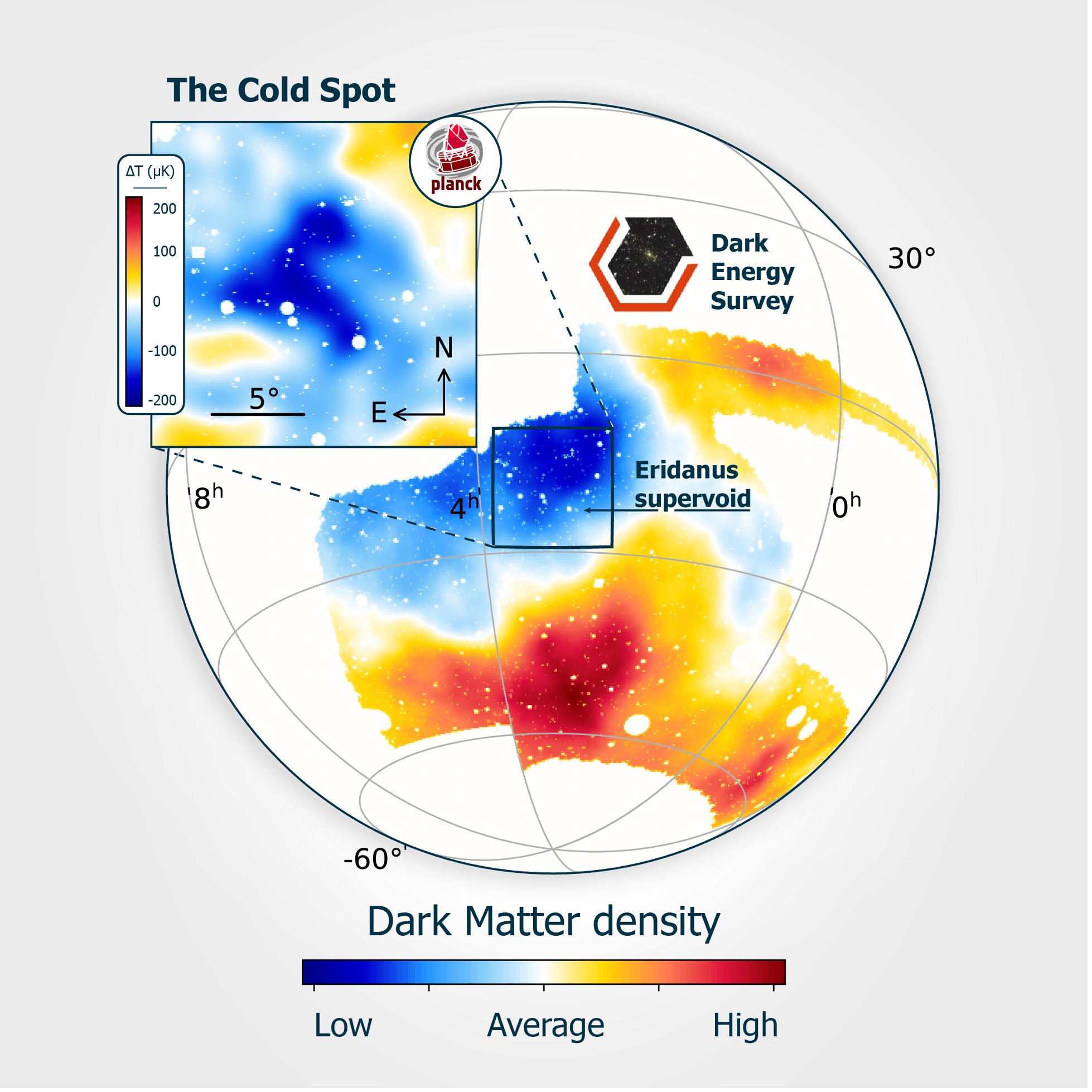

The distribution of background radiation measurements offers another empirical handle on the problem. Currently, a histogram of temperature readings at different locations on the sky traces out a bell curve — a Gaussian. Any deviation from that generic shape would reveal what physics was in play early on. “Primordial non-Gaussianity has to do with the interactions and the number of fields that were involved in inflation,” says Eva Silverstein of Stanford University.

A bounce would require gravitational effects beyond those of Einstein’s theory, and cosmological observations can look for those. “It’s not something that would typically occur, because gravity is attractive, so if you start contracting, you’re going to collide,” says Claudia de Rham of Imperial College London. She and Gabadadze have explored modifications to gravity that not only might let the universe bounce, but would illuminate the mysteries of dark energy. Modified-gravity theories are a steppingstone to a full quantum theory of gravity and, as such, need to satisfy certain general principles. Those principles, along with observations, narrow the range of allowed modifications. “That really constrains your allowed region of parameter space by combining observations and theory priors,” she says.

Once cosmologists open the door to modified gravity, all sorts of new phenomena come rushing in, and bounces are almost the least of it. Frans Pretorius of Princeton, an expert in computer analysis of Einsteinian gravity, has been simulating post-Einsteinian gravity. In one case, he and his students were tracking the formation of black holes when the modified-gravity equations suddenly ceased to operate in time. They had changed their mathematical character from one that evolves to one that remains in a steady state. “When something like this happens, we have no idea how to interpret it,” he says.

As impatient as theorists may be to settle what happened at the dawn of time, or whether time even had a dawn, Keating says his team plans to take it slow. They don’t want to pass judgment before chasing down every possible source of error, not least their own potential confirmation bias, of which any scientist should be acutely aware. “We spend so much time ruminating on what could go wrong,” he says, “we almost need a psychotherapist to help us with our self-doubt.”