RACE IN AMERICA

In a

short essay published earlier this week, Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch wrote that the recent killing in Minnesota of

George Floyd has forced the country to “confront the reality that, despite gains made in the past 50 years, we are still a nation riven by inequality and racial division.”

Amid escalating clashes between protesters and police, discussing race—from the inequity embedded in American institutions to the United States’ long, painful history of anti-black violence—is an essential step in sparking meaningful societal change. To support those struggling to begin these difficult conversations, the Smithsonian’s

National Museum of African American History and Culture recently launched a “

Talking About Race” portal featuring “tools and guidance” for educators, parents, caregivers and other people committed to equity.

“Talking About Race” joins a vast trove of resources from the Smithsonian Institution dedicated to understanding what Bunch describes as America’s “tortured racial past.” From Smithsonian magazine articles on

slavery’s Trail of Tears and the disturbing

resilience of scientific racism to the National Museum of American History’s

collection of Black History Month resources for educators and a

Sidedoor podcast on the Tulsa Race Massacre, these 158 resources are designed to foster an equal society, encourage commitment to unbiased choices and promote antiracism in all aspects of life. Listings are bolded and organized by category.

Historical Context

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/93/17/9317bc68-84d5-4342-8809-e5c2e8c8c6d7/nmaahc-jn2012-1181-000001.jpg) |

| Shackles used in the transatlantic slave trade (NMAAHC) |

Take, for instance, the story of

John Casor. Originally an indentured servant of African descent, Casor lost a 1654 or 1655 court case convened to determine whether his contract had lapsed. He became the first individual declared a slave for life in the United States.

Manuel Vidau, a Yoruba man who was captured and sold to traders some 200 years after Casor’s enslavement, later shared an account of his life with the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which documented his remarkable story—after a decade of enslavement in Cuba, he purchased a share in a lottery ticket and won enough money to buy his freedom—in records now available on the digital database “

Freedom Narratives.” (A separate, similarly document-based

online resource emphasizes individuals described in

fugitive slave ads, which historian

Joshua Rothman describes as “sort of a little biography” providing insights on their subjects’ appearance and attire.)

Finally, consider the life of

Matilda McCrear, the last known survivor of the transatlantic slave trade. Kidnapped from West Africa and brought to the U.S. on the

Clotilda, she arrived in Mobile, Alabama, in July 1860—more than 50 years after Congress had outlawed the import of enslaved labor. McCrear, who died in 1940 at the age of 81 or 82, “

displayed a determined, even defiant streak” in her later life, wrote Brigit Katz earlier this year. She refused to use her former owner’s last name, wore her hair in traditional Yoruba style and had a decades-long relationship with a white German man.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/19/4a/194a3435-712d-424f-ad2d-09ee04ccc14b/clotilda.jpg) |

Matilda McCrear died in 1940 at the age of 81 or 82. (Newcastle University) |

Accurately representing slavery might require an

updated vocabulary, argued historian

Michael Landis in 2015: Outdated “[t]erms like ‘compromise’ or ‘plantation’ served either to reassure worried Americans in a Cold War world, or uphold a white supremacist, sexist interpretation of the past.” Rather than referring to the

Compromise of 1850, call it the Appeasement of 1850—a term that better describes “the uneven nature of the agreement,” according to Landis. Smithsonian scholar

Christopher Wilson wrote, too, that widespread framing of the Civil War as a battle between equal entities

lends legitimacy to the Confederacy, which was not a nation in its own right, but an “illegitimate rebellion and unrecognized political entity.” A 2018 Smithsonian magazine investigation found that the literal

costs of the Confederacy are immense: In the decade prior, American taxpayers contributed $40 million to the maintenance of

Confederate monuments and heritage organizations.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6d/5b/6d5b0523-79e6-4b9e-bbcf-5ffb70bb18ff/nmaahc-2008_9_26_001.jpg) |

| Carte-de-visite of women and children in a cotton field, c. 1860s (NMAAHC) |

To better understand the immense brutality ingrained in enslaved individuals’ everyday lives, read up on Louisiana’s

Whitney Plantation Museum, which acts as “part reminder of the scars of institutional bondage, part mausoleum for dozens of enslaved people who worked (and died) in [its] sugar fields, … [and] monument to the terror of slavery,” as Jared Keller observed in 2016. Visitors begin their tour in a historic church populated by clay sculptures of children who died on the plantation’s grounds, then move on to a series of granite slabs engraved with hundreds of enslaved African Americans’ names. Scattered throughout the experience are stories of the violence inflicted by overseers.

The

Whitney Plantation Museum is at the forefront of a vanguard of historical sites working to confront their racist pasts. In recent years, exhibitions, oral history projects and other initiatives have highlighted the enslaved people whose labor powered such landmarks as

Mount Vernon, the

White House and

Monticello. At the same time, historians are increasingly calling attention to major historical figures’ own

slave-holding legacies: From

Thomas Jefferson to

George Washington, William Clark of

Lewis and Clark,

Francis Scott Key, and other

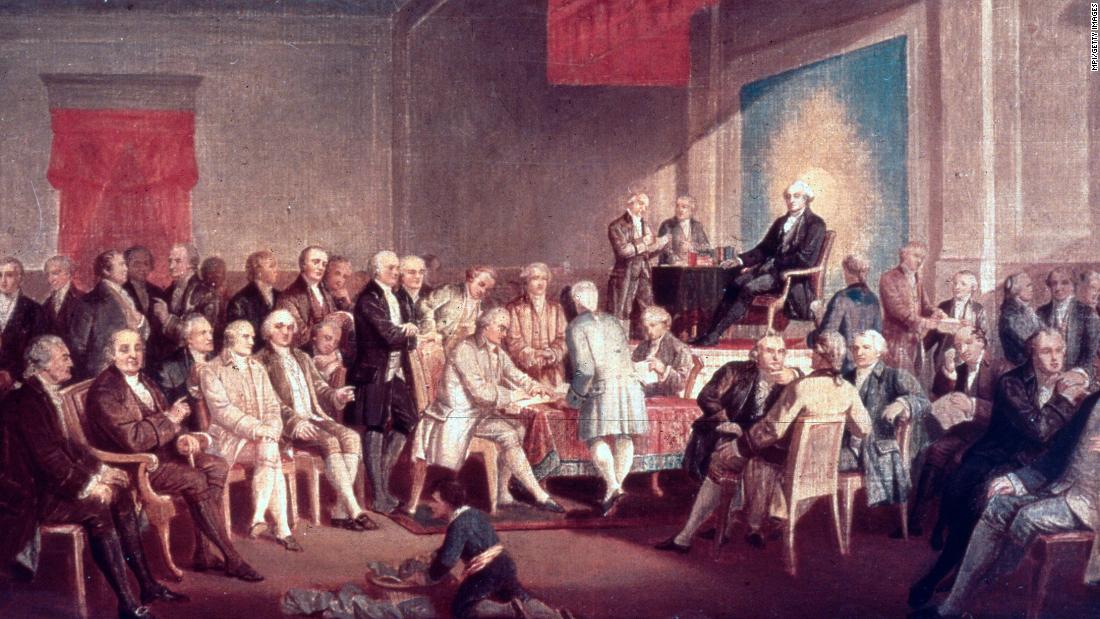

Founding Fathers, many American icons were complicit in upholding the institution of slavery.

Washington,

Jefferson,

James Madison and

Aaron Burr, among others, sexually abused enslaved females working in their households and had oft-overlooked biracial families.

|

| A stereograph of the slave market in Atlanta, Georgia (NMAAHC) |

Though Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the decree took two-and-a-half years to fully enact. June 19, 1865—the day Union Gen. Gordon Granger informed the enslaved individuals of Galveston, Texas, that they were officially free—is now known as Juneteenth: America’s “second independence day,” according to NMAAHC. Initially celebrated mainly in Texas, Juneteenth spread across the country as African Americans fled the South in what is now called the Great Migration.

At the onset of that mass movement in 1916, 90 percent of African Americans still lived in the South, where they were “held captive by the virtual slavery of sharecropping and debt peonage and isolated from the rest of the country,” as Isabel Wilkerson wrote in 2016. (Sharecropping, a system in which formerly enslaved people became tenant farmers and lived in “converted” slave cabins, was the impetus for the 1919 Elaine Massacre, which found white soldiers collaborating with local vigilantes to kill at least 200 sharecroppers who dared to criticize their low wages.) By the time the Great Migration—famously chronicled by artist Jacob Lawrence—ended in the 1970s, 47 percent of African Americans called the northern and western United States home.

Conditions outside the Deep South were more favorable than those within the region, but the “hostility and hierarchies that fed the Southern caste system” remained major obstacles for black migrants in all areas of the country, according to Wilkerson. Low-paying jobs, redlining, restrictive housing covenants and rampant discrimination limited opportunities, creating inequality that would eventually give rise to the civil rights movement.

“The Great Migration was the first big step that the nation’s servant class ever took without asking,” Wilkerson explained. “ … It was about agency for a people who had been denied it, who had geography as the only tool at their disposal. It was an expression of faith, despite the terrors they had survived, that the country whose wealth had been created by their ancestors’ unpaid labor might do right by them.”

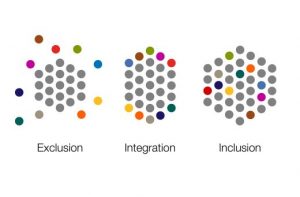

Systemic Inequality

Racial, economic and educational disparities are deeply entrenched in U.S. institutions. Though the Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal,” American democracy has historically—and often violently—excluded certain groups. “Democracy means everybody can participate, it means you are sharing power with people you don’t know, don’t understand, might not even like,” said National Museum of American History curator Harry Rubenstein in 2017. “That’s the bargain. And some people over time have felt very threatened by that notion.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/d6/bb/d6bbf57c-5330-4b4f-b5fd-79b09196e885/nmaahc-2011_155_211_001.jpg) |

An undated sterograph of black soldiers returning from France after fighting in World War I (NMAAHC) |

Among the most heartbreaking examples of structural racism’s subtle effects are accounts shared by black children. In the late 1970s, when Lebert F. Lester II was 8 or 9 years old, he started building a sand castle during a trip to the

Connecticut shore. A young white girl joined him but was quickly taken away by her father. Lester recalled the girl returning, only to ask him, “Why don’t [you] just go in the water and wash it off?” Lester says., “I was so confused—I only figured out later she meant my complexion.” Two decades earlier, in 1957, 15-year-old

Minnijean Brown had arrived at Little Rock Central High School with high hopes of “making friends, going to dances and singing in the chorus.” Instead, she and the rest of the

Little Rock Nine—a group of black students selected to attend the formerly all-white academy after

Brown v. Board of Education desegregated public schools—were subjected to daily verbal and physical assaults. Around the same time, photographer

John G. Zimmerman captured snapshots of racial politics in the South that included comparisons of black families waiting in long lines for polio inoculations as white children received speedy treatment.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/76/38/763805c9-ffca-41a3-8c52-8e5f7cd066c2/nmaahc-2011_17_201.jpg) |

Seven of the Little Rock Nine, including Melba Pattillo Beals, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Jefferson Thomas, Elizabeth Eckford, Thelma Mothershed-Wair, Terrence Roberts and Gloria Ray Karlmark, meet at the home of Daisy Bates. (NMAAHC, gift of Elmer J. Whiting, III ©Gertrude Samuels) |

In 1968, the

Kerner Commission, a group convened by President Lyndon Johnson, found that white racism, not black anger, was the impetus for the widespread civil unrest sweeping the nation. As Alice George wrote in 2018, the commission’s report suggested that “[b]ad policing practices, a flawed justice system, unscrupulous consumer credit practices, poor or inadequate housing, high unemployment, voter suppression and other culturally embedded forms of racial discrimination all converged to propel violent upheaval.” Few listened to the findings, let alone its suggestion of aggressive government spending aimed at leveling the playing field. Instead, the country embraced a different cause:

space travel. The day after the 1969 moon landing, the leading black paper the New York Amsterdam News ran a story stating, “Yesterday, the moon. Tomorrow, maybe us.”

Fifty years after the Kerner Report’s release, a

separate study assessed how much had changed; it concluded that conditions had actually worsened. In 2017, black unemployment was higher than in 1968, as was the rate of incarcerated individuals who were black. The wealth gap had also increased substantially, with the median white family having ten times more wealth than the median black family. “We are resegregating our cities and our schools, condemning millions of kids to inferior education and taking away their real possibility of getting out of poverty,” said Fred Harris, the last surviving member of the Kerner Commission, following the 2018 study’s release.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/fe/74/fe7488a2-1c4f-4bcb-b736-57d64089f4ec/nmaahc-2011_57_11_8.jpg) |

The Kerner Commission confirmed that nervous police and National Guardsmen sometimes fired their weapons recklessly after hearing gunshots. Above, police patrol the streets during the 1967 Newark Riots. (© Bud Lee, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture) |

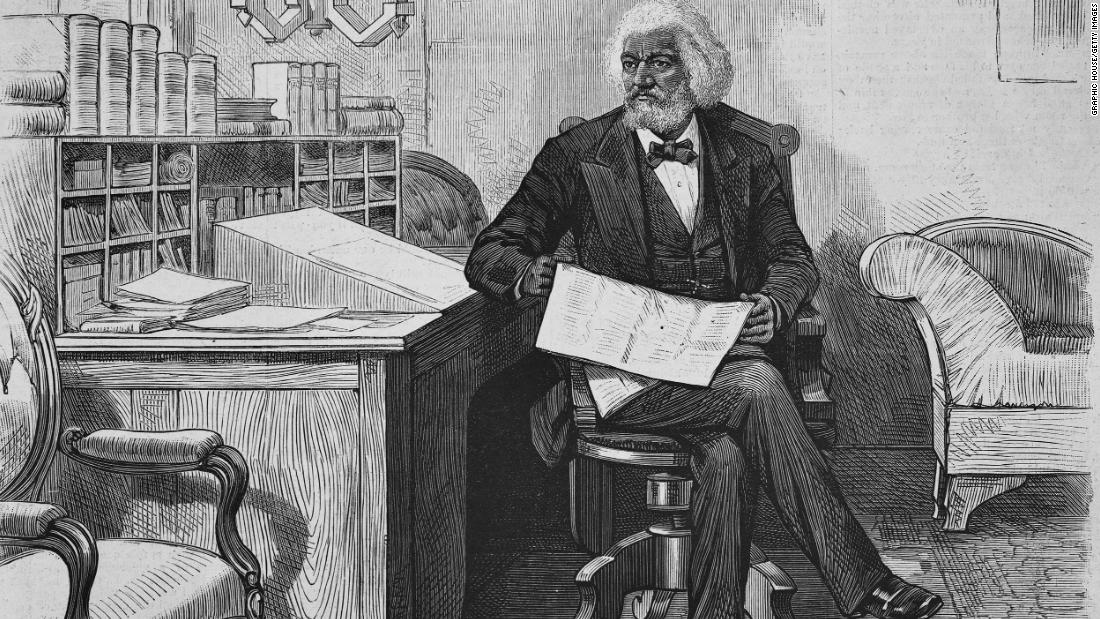

Today,

scientific racism—grounded in such faulty practices as eugenics and the treatment of race “as a crude proxy for myriad social and environmental factors,” writes Ramin Skibba—persists despite overwhelming evidence that race has only social, not biological, meaning. Black scholars including

Mamie Phipps Clark, a psychologist whose research on racial identity in children helped end segregation in schools, and

Rebecca J. Cole, a 19th-century physician and advocate who challenged the idea that black communities were destined for death and disease, have helped overturn some of these biases. But a 2015 survey found that 48 percent of black and Latina women scientists, respectively, still report being

mistaken for custodial or administrative staff. Even

artificial intelligence exhibits racial biases, many of which are introduced by lab staff and crowdsourced workers who program their own conscious and unconscious opinions into algorithms.

Anti-Black Violence

In addition to enduring centuries of enslavement, exploitation and inequality, African Americans have long been the targets of racially charged physical violence. Per the Alabama-based

Equal Justice Initiative, more than

4,400 lynchings—mob killings undertaken without legal authority—took place in the U.S. between the end of Reconstruction and World War II.

|

A house left smoldering after racial unrest broke out in Springfield, |

One of the earliest instances of Reconstruction-era racial violence took place in

Opelousas, Louisiana, in September 1868. Two months ahead of the presidential election, Southern white Democrats started terrorizing Republican opponents who appeared poised to secure victory at the polls. On September 28, a group of men attacked 18-year-old schoolteacher Emerson Bentley, who had already attracted ire for teaching African American students, after he published an account of local Democrats’ intimidation of Republicans. Bentley escaped with his life, but 27 of the 29 African Americans who arrived on the scene to help him were summarily executed. Over the next two weeks, vigilante terror led to the deaths of some 250 people, the majority of whom were black.

In April 1873, another spate of violence rocked Louisiana. The

Colfax Massacre, described by historian Eric Foner as the “bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era,” unfolded under similar circumstances as Opelousas, with tensions between Democrats and Republicans culminating in the deaths of between 60 and 150 African Americans, as well as three white men.

Between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s, multiple massacres broke out in response to false allegations that young black men had raped or otherwise assaulted white women. In August 1908, a mob

terrorized African American neighborhoods across Springfield, Illinois, vandalizing black-owned businesses, setting fire to the homes of black residents, beating those unable to flee and lynching at least two people. Local authorities, argues historian

Roberta Senechal, were “ineffectual at best, complicit at worst.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/5e/84/5e8491dd-6096-4821-a323-e5afd5c07083/1024px-tulsaraceriot-1921.png) |

During the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, mobs destroyed almost 40 blocks

of a neighborhood known as "Black Wall Street." (Library of Congress) |

False accusations also sparked a

July 1919 race riot in Washington, D.C. and the

Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, which was most recently dramatized in the HBO series “

Watchmen.” As African American History Museum curator

Paul Gardullo tells Smithsonian, tensions related to Tulsa’s economy underpinned

the violence: Forced to settle on what was thought to be worthless land, African Americans and Native Americans struck oil and proceeded to transform the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa into a prosperous community known as “Black Wall Street.” According to Gardullo, “It was the frustration of poor whites not knowing what to do with a successful black community, and in coalition with the city government [they] were given permission to do what they did.”

Over the course of two days in spring 1921, the

Tulsa Race Massacre claimed the lives of an estimated 300 black Tulsans and displaced another 10,000. Mobs burned down at least 1,256 residences, churches, schools and businesses and destroyed almost 40 blocks of Greenwood. As the Sidedoor episode “

Confronting the Past” notes, “No one knows how many people died, no one was ever convicted, and no one really talked about it nearly a century later.”

Economic injustice also led to the

East St. Louis Race War of 1917. This labor dispute-turned-deadly found “people’s houses being set ablaze, … people being shot when they tried to flee, some trying to swim to the other side of the Mississippi while being shot at by white mobs with rifles, others being dragged out of street cars and beaten and hanged from street lamps,” recalled Dhati Kennedy, the son of a survivor who witnessed the devastation firsthand. Official counts place the death toll at 39 black and 9 white individuals, but locals argue that the real toll was closer to 100.

A watershed moment for the burgeoning civil rights movement was the 1955 murder of 14-year-old

Emmett Till. Accused of whistling at a white woman while

visiting family members in Mississippi, he was kidnapped, tortured and killed. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to give her son an open-casket funeral, forcing the world to

confront the image of his disfigured, decomposing body. (

Visuals, including photographs, movies, television clips and artwork, played a key role in advancing the movement.) The two white men responsible for Till’s murder were acquitted by an all-white jury. A marker at the site where the teenager’s body was recovered has been

vandalized at least three times since its placement in 2007.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/b9/63/b96308dd-3056-4d87-909c-c7aabc05c8f7/nmaahc-2013_92_003.jpg) |

| Family members grieving at Emmett Till's funeral (NMAAHC) |

The form of anti-black violence with the most striking parallels to contemporary conversations is

police brutality. As Katie Nodjimbadem reported in 2017, a regional

crime survey of late 1920s Chicago and Cook County, Illinois, found that while African Americans constituted just 5 percent of the area’s population, they made up 30 percent of the victims of police killings. Civil rights protests exacerbated tensions between African Americans and police, with events like the

Orangeburg Massacre of 1968, in which law enforcement officers shot and killed three student activists at South Carolina State College, and the

Glenville shootout, which left three police officers, three black nationalists and one civilian dead, fostering mistrust between the two groups.

Today, this legacy is exemplified by

broken windows policing, a controversial approach that encourages racial profiling and targets African American and Latino communities. “What we see is a continuation of an unequal relationship that has been exacerbated, made worse if you will, by the militarization and the increase in fire power of police forces around the country,”

William Pretzer, senior curator at NMAAHC, told Smithsonian in 2017.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/1b/55/1b558d42-ae6d-453b-936b-e42aa61d6654/2012_169_6.jpg) |

Police Disperse Marchers with Tear Gas by unidentified photographer, 1966 (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Howard Greenberg Gallery) |

Protest

The history of

protest and revolt in the United States is inextricably linked with the racial violence detailed above.

Prior to the Civil War, enslaved individuals rarely revolted outright.

Nat Turner, whose 1831 insurrection ended in his execution, was one of the rare exceptions. A

fervent Christian, he drew inspiration from the Bible. His

personal copy, now housed in the collections of the African American History Museum, represented the “possibility of something else for himself and for those around him,” curator Mary Ellis told

Smithsonian’s Victoria Dawson in 2016.

Other enslaved African Americans practiced less risky forms of resistance, including working slowly, breaking tools and setting objects on fire. “Slave rebellions, though few and small in size in America, were invariably bloody,” wrote Dawson. “Indeed, death was all but certain.”

One of the few successful uprisings of the period was the

Creole Rebellion. In the fall of 1841, 128 enslaved African Americans traveling aboard The Creole mutinied against its crew, forcing their former captors to sail the brig to the British West Indies, where slavery was abolished and they could gain immediate freedom.

An

April 1712 revolt found enslaved New Yorkers setting fire to white-owned buildings and firing on slaveholders. Quickly outnumbered, the group fled but was tracked to a nearby swamp; though several members were spared, the majority were publicly executed, and in the years following the uprising, the city enacted laws limiting enslaved individuals’ already scant freedom. In 1811, meanwhile, more than 500 African Americans marched on New Orleans while chanting “Freedom or Death.” Though the

German Coast uprising was brutally suppressed, historian

Daniel Rasmussen argues that it “had been much larger—and come much closer to succeeding—than the planters and American officials let on.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/16/06/16063c51-b65d-4769-819e-b24ad1e18175/woolworth-four-19601.jpg) |

The lasting legacy of the Greensboro Four (above from left: David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Jibreel Khazan and Joseph McNeil) was how the courageous moment grew |

Some 150 years after what Rasmussen deems America’s “

largest slave revolt,” the civil rights movement ushered in a different kind of protest. In 1955, police arrested

Rosa Parks for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white passenger (“I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it any more,” she later wrote). The ensuing

Montgomery bus boycott, in which black passengers refused to ride public transit until officials met their demands, led the Supreme Court to rule segregated buses unconstitutional. Five years later, the

Greensboro Four similarly took a stand, ironically by staging a sit-in at a

Woolworth’s lunch counter. As

Christopher Wilson wrote ahead of the 60th anniversary of the event, “What made Greensboro different [from

other sit-ins] was how it grew from a courageous moment to a revolutionary movement.”

During the 1950s and ’60s,

civil rights leaders adopted varying approaches to protest:

Malcolm X, a staunch proponent of black nationalism who called for equality by “any means necessary,” “made tangible the anger and frustration of African Americans who were simply catching hell,” according to journalist Allison Keyes. He repeated the

same argument “over and over again,” wrote academic and activist

Cornel West in 2015: “What do you think you would do after 400 years of slavery and Jim Crow and lynching? Do you think you would respond nonviolently? What’s your history like? Let’s look at how you have responded when you were oppressed. George Washington—revolutionary guerrilla fighter!’”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6a/9c/6a9c3344-4b98-4f3e-988b-d388c1f5853c/gettyimages-113491383.jpg) |

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X wait for a press conference on March 26, 1964. (Photo by Universal History Archive / Getty Images) |

Martin Luther King Jr. famously advocated for nonviolent protest, albeit not in the form that many think. As biographer Taylor Branch told

Smithsonian in 2015,

King’s understanding of nonviolence was more complex than is commonly argued. Unlike Mahatma Gandhi’s “passive resistance,” King believed resistance “depended on being active, using demonstrations, direct actions, to ‘amplify the message’ of the protest they were making,” according to Ron Rosenbaum. In the activist’s

own words, “[A] riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear?… It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. ”

Another key player in the civil rights movement, the militant

Black Panther Party, celebrated

black power and operated under a philosophy of “

demands and aspirations.” The group’s Ten-Point Program called for an “immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people,” as well as more controversial measures like freeing all black prisoners and exempting black men from military service. Per

NMAAHC, black power “emphasized black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration,” calling for the creation of separate African American political and cultural organizations. In doing so, the movement ensured that its proponents would attract the unwelcome attention of the FBI and other government agencies.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/bd/64/bd645528-cc59-42fd-8d11-85d8f41482e4/boys_marching.jpg) |

| Peaceful protestors march down Constitution Avenue and the National Mall on August 28, 1963. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of James H. Wallace Jr, © Jim Wallace) |

Many of the protests now viewed as emblematic of the fight for racial justice took place in the 1960s. On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 people gathered in D.C. for the

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the march, activists who attended the event detailed the experience for a Smithsonian

oral history: Entertainer Harry Belafonte observed, “We had to seize the opportunity and make our voices heard. Make those who are comfortable with our oppression—make them uncomfortable—Dr. King said that was the purpose of this mission,” while Representative John Lewis recalled, “Looking toward Union Station, we saw a sea of humanity; hundreds, thousands of people. … People literally pushed us, carried us all the way, until we reached the Washington Monument and then we walked on to the Lincoln Memorial..”

Two years after the March on Washington, King and other activists organized a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. Later called the

Selma March, the protest was dramatized in a 2014 film starring

David Oyelowo as MLK. (

Reflecting on Selma, Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch, then-director of NMAAHC, deemed it a “remarkable film” that “does not privilege the white perspective … [or] use the movement as a convenient backdrop for a conventional story.”)

Organized in response to the manifest obstacles black individuals faced when attempting to vote, the Selma March actually consisted of three separate protests. The first of these, held on March 7, 1965, ended in a tragedy now known as

Bloody Sunday. As peaceful protesters gathered on the

Edmund Pettus Bridge—named for a Confederate general and local Ku Klux Klan leader—law enforcement officers attacked them with tear gas and clubs. One week later, President

Lyndon B. Johnson offered the Selma protesters his support and introduced legislation aimed at expanding voting rights. During the third and final march, organized in the aftermath of Johnson’s announcement, tens of thousands of protesters (protected by the National Guard and personally led by King) converged on Montgomery. Along the way, interior designer Carl Benkert used a hidden reel-to-reel tape recorder to document the

sounds—and specifically songs—of the event.

|

Civil rights leaders stand with protesters at the 1963

March on Washington. (U.S. Archives) |

The protests of the early and mid-1960s culminated in the widespread unrest of 1967 and 1968. For five days in July 1967, riots on a scale unseen since 1863 rocked the city of

Detroit: As Lorraine Boissoneault writes, “Looters prowled the streets, arsonists set buildings on fire, civilian snipers took position from rooftops and police shot and arrested citizens indiscriminately.” Systemic injustice in such areas as housing, jobs and education contributed to the uprising, but police brutality was the driving factor behind the violence. By the end of the riots, 43 people were dead. Hundreds sustained injuries, and more than 7,000 were arrested.

The Detroit riots of 1967 prefaced the seismic changes of

1968. As Matthew Twombly wrote in 2018, movements including the Vietnam War, the Cold War, civil rights, human rights and youth culture “exploded with force in 1968,” triggering aftershocks that would resonate both in America and abroad for decades to come.

On February 1, black sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker died in a gruesome accident involving a malfunctioning garbage truck. Their deaths, compounded by Mayor Henry Loeb’s refusal to negotiate with labor representatives, led to the outbreak of the

Memphis sanitation workers’ strike—an event remembered both “as an example of powerless African Americans standing up for themselves” and as the backdrop to

King’s April 4 assassination.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/af/55/af5563b7-5342-40c9-9860-945f0a294b88/2017_76_3_001_credit-gift_of_abigail_wiebenson__sons.jpg) |

In May 1968, protesters constructed “Resurrection City,” a temporary settlement made up of 3,000 wooden tents. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Abigail Wiebenson & sons, John, Derek & Sam in honor of John Wiebenson) |

In May, thousands flocked to

Washington, D.C. for a protest King had planned prior to his death. Called the

Poor People’s Campaign, the event united racial groups from all quarters of America in a call for economic justice. Attendees constructed “

Resurrection City,” a temporary settlement made up of 3,000 wooden tents, and camped out on the National Mall for 42 days.

“While we were all in a kind of depressed state about the assassinations of King and RFK, we were trying to keep our spirits up, and keep focused on King’s ideals of humanitarian issues, the elimination of poverty and freedom,” protester Lenneal Henderson told

Smithsonian in 2018. “It was exciting to be part of something that potentially, at least, could make a difference in the lives of so many people who were in poverty around the country.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/48/ec/48ecd873-a4e6-4919-9dbf-9693a11ce133/gettyimages-1217135506.jpg) |

Protesters demonstrate on June 2, 2020, during a Black Lives Matter protest in New York City. (Photo by Johannes Eisele / AFP via Getty Images) |

Other aspects of modern protest draw directly on uprisings of earlier eras. In 2016, for instance, artist

Dread Scott updated an anti-lynching poster used by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1920s and ’30s to read “

A Black Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday.” (Scott added the words “by police.”)

Though the civil rights movement is often viewed as the result of a cohesive “grand plan” or “manifestation of the vision of the few leaders whose names we know,” the American History Museum’s Christopher Wilson argues that “the truth is there wasn’t one,

there were many and they were often competitive.”

Meaningful change required a whirlwind of revolution, adds Wilson, “but also the slow legal march. It took boycotts, petitions, news coverage, civil disobedience, marches, lawsuits, shrewd political maneuvering, fundraising, and even the violent terror campaign of the movement’s opponents—all going on [at] the same time.”

Intersectionality

In layman’s terms,

intersectionality refers to the multifaceted discrimination experienced by individuals who belong to multiple minority groups. As theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw explains in a

video published by NMAAHC, these classifications run the gamut from race to gender, gender identity, class, sexuality and disability. A black woman who identifies as a lesbian, for instance, may face prejudice based on her race, gender or sexuality.

Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality in 1989, explains the concept best: “Consider an intersection made up of many roads,” she says in the video. “The roads are the structures of race, gender, gender identity, class, sexuality, disability. And the traffic running through those roads are the practices and policies that discriminate against people. Now if an accident happens, it can be caused by cars traveling in any number of directions, and sometimes, from all of them. So if a black woman is harmed because she is in an intersection, her injury could result from discrimination from any or all directions.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/65/0e/650ef0c5-c647-49b1-91fa-f15cae6978cc/2012_83_6_001.jpg) |

A photo taken at a Free Huey Newton Rally in 1968 with five of the six women identifiable—Delores Henderson, Joyce Lee, Mary Ann Carlton, Joyce Means and Paula Hill—provides testament to those who actualized the daily operations of the Black Panther Party. (NMAAHC, gift of the Pirkle Jones Foundation, ©2011 Pirkle Jones Foundation) |

Allyship and Education

In collaboration with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, the National Museum of the American Indian has created a

toolkit that aims to “help people facilitate new conversations with and among students about the power of images and words, the challenges of memory, and the relationship between personal and national value,” says museum director Kevin Gover in a

statement. The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center offers a similarly focused resource called “

Standing Together Against Xenophobia.” As the site’s description notes, “This includes addressing not only the hatred and violence that has recently targeted people of Asian descent, but also the xenophobia that plagues our society during times of national crisis.”

Ahead of NMAAHC’s official opening in 2016, the museum hosted a series of public programs titled “

History, Rebellion, and Reconciliation.” Panels included “Ferguson: What Does This Moment Mean for America?” and “#Words Matter: Making Revolution Irresistible.” As Smithsonian reported at the time, “It was somewhat of a refrain at the

symposium that

museums can provide ‘safe,’ or even ‘sacred’ spaces, within which visitors [can] wrestle with difficult and complex topics.” Then-director Lonnie Bunch expanded on this mindset in an interview, telling Smithsonian, “Our job is to be an educational institution that uses history and culture not only to look back, not only to help us understand today, but to point us towards what we can become.” For more context on the museum’s collections, mission and place in American history, visit Smithsonian’s “

Breaking Ground” hub and NMAAHC’s

digital resources guide.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/94/80/9480f374-0b40-43e2-b111-e51bda889fba/credit-alankarchmer_220.jpg) |

The National Museum of African American History and Culture recently launched a "Talking About Race" portal. (Alan Karchmer) |

Historical examples of allyship offer both inspiration and cautionary tales for the present. Take, for example,

Albert Einstein, who famously criticized segregation as a “disease of white people” and continually used his platform to denounce racism. (The scientist’s advocacy is admittedly complicated by travel diaries that reveal his

deeply troubling views on race.)

Einstein’s near-contemporary, a white novelist named John Howard Griffin, took his supposed allyship one step further, darkening his skin and embarking on a “human odyssey through the South,” as Bruce Watson

wrote in 2011. Griffin’s chronicle of his experience, a volume titled

Black Like Me, became a surprise bestseller, refuting “the idea that minorities were acting out of paranoia,” according to scholar Gerald Early, and testifying to the veracity of black people’s accounts of racism.

“The only way I could see to bridge the gap between us,” wrote Griffin in Black Like Me, “was to become a Negro.”

Griffin, however, had the privilege of being able to shed his blackness at will—which he did after just one month of donning his makeup. By that point, Watson observed, Griffin could simply “stand no more.”

Sixty years later, what is perhaps most striking is just how little has changed. As Bunch reflected earlier this week, “The state of our democracy feels fragile and precarious.”

Addressing the racism and social inequity embedded in American society will be a “monumental task,” the secretary added. But “the past is replete with examples of ordinary people working together to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges. History is a guide to a better future and demonstrates that we can become a better society—but only if we collectively demand it from each other and from the institutions responsible for administering justice.”

*Editor’s Note, July 24, 2020: This article previously stated that some 3.9 million of the 10.7 million people who survived the harrowing two-month journey across the Middle Passage between 1525 and 1866 were ultimately enslaved in the United States. In fact, the 3.9 million figure refers to the number of enslaved individuals in the U.S. just before the Civil War. We regret the error.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/93/17/9317bc68-84d5-4342-8809-e5c2e8c8c6d7/nmaahc-jn2012-1181-000001.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/19/4a/194a3435-712d-424f-ad2d-09ee04ccc14b/clotilda.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6d/5b/6d5b0523-79e6-4b9e-bbcf-5ffb70bb18ff/nmaahc-2008_9_26_001.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/d6/bb/d6bbf57c-5330-4b4f-b5fd-79b09196e885/nmaahc-2011_155_211_001.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/76/38/763805c9-ffca-41a3-8c52-8e5f7cd066c2/nmaahc-2011_17_201.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/fe/74/fe7488a2-1c4f-4bcb-b736-57d64089f4ec/nmaahc-2011_57_11_8.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/5e/84/5e8491dd-6096-4821-a323-e5afd5c07083/1024px-tulsaraceriot-1921.png)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/b9/63/b96308dd-3056-4d87-909c-c7aabc05c8f7/nmaahc-2013_92_003.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/1b/55/1b558d42-ae6d-453b-936b-e42aa61d6654/2012_169_6.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/16/06/16063c51-b65d-4769-819e-b24ad1e18175/woolworth-four-19601.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6a/9c/6a9c3344-4b98-4f3e-988b-d388c1f5853c/gettyimages-113491383.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/bd/64/bd645528-cc59-42fd-8d11-85d8f41482e4/boys_marching.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/af/55/af5563b7-5342-40c9-9860-945f0a294b88/2017_76_3_001_credit-gift_of_abigail_wiebenson__sons.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/48/ec/48ecd873-a4e6-4919-9dbf-9693a11ce133/gettyimages-1217135506.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/65/0e/650ef0c5-c647-49b1-91fa-f15cae6978cc/2012_83_6_001.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/94/80/9480f374-0b40-43e2-b111-e51bda889fba/credit-alankarchmer_220.jpg)