|

| Beecher Family of Boston |

|

| Haarriet Elizabeth Beecher Stowe |

|

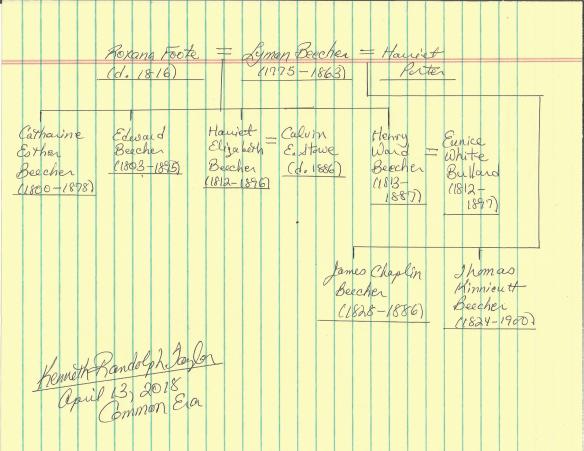

| Lyman Beecher Family Tree |

The Good and the Bad of White Christianity

R.E. Slater

August 2, 2020

My roots go back to the Beechers of Boston, all preachers and social activists. This would also include Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The Beechers were all abolitionists, suffragists, early advocates for removing children from dangerous manufacturing labor environments, for safer work places, and reduced labor hours for the common laborer with better pay. They bought slaves at Sunday Church auction services and immediately released them to freedom (cf, the Story of Pinky). Generally the Beechers were a hard preaching family for God, Gospel, Country, Social Activism, and Christian Humanism, now more commonly known as Social Justice.

Legacy of Beecher Family of Boston References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

|

| Samuel Slater, Founder of the American Textile Industry, Pawtucket, Rhode Island |

But if I go back far enough to my first American ancestor, Samuel Slater, I will find not only the Father of the American textile industry, or the Father of the American Sunday School system, but the implementer of child labor which sadly included the mutilation of their little hands by textile machinery. Of families working long hours while being preached to on Sundays of the sanctity of Puritan religious laws and dictims which encouraged hard work as unto God. And very possibly a great ignorance to the pollution of land and water in the manufacture of clothing for America. Though Samuel Slater clothed America he also acted in accordance with his Christian faith and religious upbringing.

These photos ended child labor in the US

by Lewis Hines

Lewis Hines - Vox Series on Child Labor in the US

Library of Congress - National Child Labor Committee Collection

Samuel Slater References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

From both illustrations of my family tree I find the good and the bad to Christian endeavor though I look at both instances as important contributing legacies to the early and middling histories of an evolving America. A country filled with both good and bad Christian people each looking for leadership and direction in the life of America's democratic union.

Today, in the pandemic year 2020, we find ourselves in a similar story of America as it looks to embrace the difference of others into its sadder legacies of not embracing the Native American or enslaved populations of America. A horrid practice begun by its mother country England having brought the practice of slavery to the Colonies beginning with Virginia's early cotton crops made necessary for clothing. And its tobacco crops made necessary for the human predilection for habit based social behaviors.

Over the past twenty years the opening of the 21st Century has been a volley across America's bows by popular forces struggling with one another. The struggle of class and racial neglect, resistance, and political warfare for societal, economic, educational, and legal equality and opportunity. The majority white population of America has scattered across various lines of embrace or rejection. The minority populations are as divided as well, wishing all the privileges of American citizenship but concerned whether opening America's democratic union too wide might allow too many into America's privileged status.

Part of the American Church's struggle has been its intersection between Jesus' Deeds with Jesus' Words. Some churches like to walk the talk while other churches like to talk the walk. To each is the difficulty of doing both together at the same time. Social Justice ministries differ widely from theological dogmatic ministries. And when one side disparages the other side - either for its lack of community ministries or for its lack of paying attention to whatever "religious truths" happen to be vogue in that decade - both seem to speak past each other.

White supremacy and racism has exasperated these nominal Christian positions forcing the church to take cultural sides which most favor its character. Unfortunately, Christian doctrines denying the social gospel while elevating Empire ethics and morality as substitute for Jesus' deeds is the worst choice of all. It oppresses, harms, and divides societies of difference rather than strengthening them. It excludes, and seeks to exclude completely by nestling up to power, wealth, and politic preferencing. Whereas Jesus had harsh words for ungodly rulers and governances He reserved His wrath especially for the religious who had become tone-deaf to the harm they were doing to God's kingdom on earth.

And so, let us turn our attention today to White Christian America and what we might do within our faiths to be more sensitive to white nationalism and racism, more helpful in undoing the shackling bounds we have placed our brothers and sisters of another color or religion in, and in creating a greater freedom and liberty that is equitable and fair to all across our borderlands. To see America's pluralism and pursuit of justice as a just cause, a merciful duty, requiring Christian ethics to go beyond the borderlands of its creeds and beliefs into the hinterlands of the world that America may truly become "A Beacon on the Hill of Democracy."

Peace, my friends.

R.E. Slater

August 2, 2020

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Select Quote from White Too Long author

Robert P. Jones

"In my day job as CEO of PRRI, we’re repeatedly confronted with public opinion data that suggests white Christians really have a blind spot in seeing racial injustice and particularly structural racism. So it was a combination of really reckoning with my own family’s history, together with seeing patterns in the data that just made it so clear that this is not a story of some distant past, but this is very much still in the DNA of white Christianity today.

"They tell themselves that their version of Christianity is God’s means of bringing salvation to the lost world. That they are the embodiment of everything that is good about America, that they are pillars of the community. But that story doesn’t stand up to very much scrutiny.

"Along with the good that white Christian churches have done — building hospitals, orphanages and other civic institutions — they have also pronounced the blessings of God on slavery. They were the main legitimizers of a massive resistance to civil rights and have very consistently been on the wrong side of those issues. You can certainly point to the abolitionist movement and say, yes, that has Christian roots. But the bigger picture is that there were many, many more white Christians resisting desegregation than were on the abolitionists’ side of things."

|

| Amazon Link |

The New York Times best-selling book exploring the counterproductive reactions white people have when their assumptions about race are challenged, and how these reactions maintain racial inequality.

In this “vital, necessary, and beautiful book” (Michael Eric Dyson), anti-racist educator Robin DiAngelo deftly illuminates the phenomenon of white fragility and “allows us to understand racism as a practice not restricted to ‘bad people’ (Claudia Rankine). Referring to the defensive moves that white people make when challenged racially, white fragility is characterized by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and by behaviors including argumentation and silence. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium and prevent any meaningful cross-racial dialogue. In this in-depth exploration, DiAngelo examines how white fragility develops, how it protects racial inequality, and what we can do to engage more constructively.

|

| Amazon Link |

Robert P. Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, spells out the profound political and cultural consequences of a new reality—that America is no longer a majority white Christian nation. “Quite possibly the most illuminating text for this election year” (The New York Times Book Review).

For most of our nation’s history, White Christian America (WCA) set the tone for our national policy and shaped American ideals. But especially since the 1990s, WCA has steadily lost influence, following declines within both its mainline and evangelical branches. Today, America is no longer demographically or culturally a majority white, Christian nation.

Drawing on more than four decades of polling data, The End of White Christian America explains and analyzes the waning vitality of WCA. Robert P. Jones argues that the visceral nature of today’s most heated issues—the vociferous arguments around same-sex marriage and religious and sexual liberty, the rise of the Tea Party following the election of our first black president, and stark disagreements between black and white Americans over the fairness of the criminal justice system—can only be understood against the backdrop of white Christians’ anxieties as America’s racial and religious topography shifts around them.

Beyond 2016, the descendants of WCA will lack the political power they once had to set the terms of the nation’s debate over values and morals and to determine election outcomes. Looking ahead, Jones forecasts the ways that they might adjust to find their place in the new America—and the consequences for us all if they don’t. “Jones’s analysis is an insightful combination of history, sociology, religious studies, and political science….This book will be of interest to a wide range of readers across the political spectrum” (Library Journal).

|

| Amazon Link |

Drawing on history, public opinion surveys, and personal experience, Robert P. Jones delivers a provocative examination of the unholy relationship between American Christianity and white supremacy, and issues an urgent call for white Christians to reckon with this legacy for the sake of themselves and the nation.

As the nation grapples with demographic changes and the legacy of racism in America, Christianity’s role as a cornerstone of white supremacy has been largely overlooked. But white Christians—from evangelicals in the South to mainline Protestants in the Midwest and Catholics in the Northeast—have not just been complacent or complicit; rather, as the dominant cultural power, they have constructed and sustained a project of protecting white supremacy and opposing black equality that has framed the entire American story.

With his family’s 1815 Bible in one hand and contemporary public opinion surveys by Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) in the other, Robert P. Jones delivers a groundbreaking analysis of the repressed history of the symbiotic relationship between Christianity and white supremacy. White Too Long demonstrates how deeply racist attitudes have become embedded in the DNA of white Christian identity over time and calls for an honest reckoning with a complicated, painful, and even shameful past. Jones challenges white Christians to acknowledge that public apologies are not enough—accepting responsibility for the past requires work toward repair in the present.

White Too Long is not an appeal to altruism. Drawing on lessons gleaned from case studies of communities beginning to face these challenges, Jones argues that contemporary white Christians must confront these unsettling truths because this is the only way to salvage the integrity of their faith and their own identities. More broadly, it is no exaggeration to say that not just the future of white Christianity but the outcome of the American experiment is at stake.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

POLITICS

White Supremacy Shaped American Christianity, Researcher Says

07/26/2020 12:00 pm

Racist theology is deeply embedded in the DNA of white Christian churches, influencing even their theology on salvation, PRRI founder Robert Jones argues in a new book.

Robert Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, comes from a line of white American Christians that stretches back before the Revolutionary War. His ancestors weren’t large plantation owners or Confederate generals, or ― as far as he knows ― active members of the Ku Klux Klan. For much of his life, Jones believed the “unremarkable” nature of his family’s background meant that white supremacy wasn’t a part of their history.

But he’s recently started to tell a different kind of story ― one that acknowledges that white privilege shaped his family’s sojourn on American soil.

His ancestors were wealthy enough to own slaves, Jones said. The family settled in Georgia on land the government seized from indigenous Creek and Cherokee people. They became Southern Baptists, part of a denomination founded in 1845 on the belief that it was perfectly moral for Christians to be slave owners.

Decades later, after Jones’s great-grandfather was killed in a clay mining accident, co-workers allegedly killed an innocent Black worker in retaliation. Jones still remembers how satisfied his great-uncle appeared while retelling that story, as if this arbitrary and unjustified act of racial violence helped balance the scales after a white man’s death.

It wouldn’t be hard for many white Christians to find examples of white supremacy’s claims on their own family’s trees, Jones said. But white Christians’ image of themselves and their religion has been warped by what Jones calls “white-supremacy-induced amnesia.”

Jones wrestles with that amnesia in his new book, “White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity.” He argues that white Christians ― from evangelicals in the South to mainline Protestants in the Midwest to Catholics in the Northeast ― weren’t just complacent onlookers while political leaders debated what to do about slavery, segregation and discrimination. White supremacist theology played a key role in shaping the American church from the very beginning, influencing not just the way denominations formed but also white Christians’ theology about salvation itself.

HuffPost spoke with Jones about his book earlier in July. Just as his own family history would be incomplete without acknowledging the influences of white supremacy, Jones said it’s impossible to talk about American Christianity without recognizing that racism helped shape the church.

|

| Robert Jones is the CEO and founder of the Public Religion Research Institute, a nonprofit organization that conducts research on religion, culture and politics | Courtesy of PRRI |

How did your own eyes open to the ways that white Christianity and white supremacy are entangled?

I grew up in Jackson, Mississippi. I was deeply immersed in white Southern Baptist evangelical culture. I was that kid who was always at church, four to five times a week. I have a degree from a Southern Baptist college, and I have a Master of Divinity degree from a Southern Baptist seminary. But it wasn’t until I was in grad school in my 30s that I really began to examine the history of my denomination’s direct ties to slavery.

Along with that, in my day job as CEO of PRRI, we’re repeatedly confronted with public opinion data that suggests white Christians really have a blind spot in seeing racial injustice and particularly structural racism. So it was a combination of really reckoning with my own family’s history, together with seeing patterns in the data that just made it so clear that this is not a story of some distant past, but this is very much still in the DNA of white Christianity today.

So what is the story that white Christians tell themselves about the church’s relationship to white supremacy?

They tell themselves that their version of Christianity is God’s means of bringing salvation to the lost world. That they are the embodiment of everything that is good about America, that they are pillars of the community. But that story doesn’t stand up to very much scrutiny.

Along with the good that white Christian churches have done — building hospitals, orphanages and other civic institutions — they have also pronounced the blessings of God on slavery. They were the main legitimizers of a massive resistance to civil rights and have very consistently been on the wrong side of those issues. You can certainly point to the abolitionist movement and say, yes, that has Christian roots. But the bigger picture is that there were many, many more white Christians resisting desegregation than were on the abolitionists’ side of things.

The legacy of this ― the proof in the pudding ― is what public opinion looks like today. White Christians ― evangelicals, mainline Protestants and Catholics ― are 30 percentage points more likely than religiously unaffiliated whites to say the Confederate flag is more a symbol of Southern pride than a symbol of racism. If you ask whether the killings of Black men by police are isolated incidents or part of a pattern, white Christians are twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated whites to say these are isolated instances. They have a very difficult time connecting the dots and seeing the structural justice issues at stake.

You spend some time in the book explaining that white mainline Protestants and white Catholics were also complicit in white supremacy. Why did you feel that it was important to point that out?

It’s important not to dismiss this as a question of Southern culture. In the book, I developed a racism index, a broad index of 15 different racial attitude questions. I put those into a statistical model that controlled for things like Southern regionalism, Republican identity, education level, all kinds of things that could be driving these attitudes that have nothing to do with Christian identity. Even when I controlled for all of those things, white Christian identity in itself is directly connected to racist attitudes.

Some of this data gets dismissed by white Christians who say those numbers are muddied because they include people who just claim to be Christian but never darken the door of a church. But the data refutes that quite soundly. In fact, among white Christians overall, there’s a positive relationship between their religious identity and holding more racist views. Perhaps most disturbing is that among white evangelicals, the relationship between holding racist views and white Christian identity is actually stronger among more frequent church attenders. That ought to be a cause for a deep soul-searching among white Christians overall and among white evangelicals in particular.

|

| White evangelicals who attend church frequently are more likely than less frequent attenders to hold racist views, Robert Jones argues in a new book | Middelveld via Getty Images |

How do you think racism helped shape white American Christians’ theology about salvation?

I think it’s helpful to go back and imagine what early church history in the U.S. looked like in the colonies. There was this sense that white people were God’s chosen instruments to civilize the U.S. and the world. It would not be unusual for white slave owners to bring enslaved people to church with them on Sunday morning. Whites would sit in the front and enslaved people would sit in the back. That context certainly shapes the way Christian theology and practices form. You’re not going to preach a lot of liberation, freedom and equality from the pulpit. You’re going to preach more about obedience to the master and fulfilling your roles, those kinds of things. I think that fundamentally distorted American white Christianity from the beginning.

One of the ways this happened is that salvation became this very hyper-individualized concept. So it becomes about a person’s individual relationship to God through Jesus, and it’s very much about personal morality and piety. It was this very privatized and cordoned off way of thinking about spirituality and Christianity. This developed by necessity and by design, as a way of thinking about salvation that would be consistent with a world that was already committed to the idea of white supremacy.

I’d like to get your thoughts on how white supremacy influenced how white Christians think about the purpose of government. In my own reporting, I’ve seen white evangelical Christians express the idea that, when it comes to issues such as immigration and policing, it’s the government’s God-given duty to keep the country safe, while it’s individual Christians’ duty to be charitable and care for the poor. Do you think this way of thinking has racist roots?

I do think whenever white Christians declare or draw lines between what is biblical and what is political, I would look for white supremacy to be at work. This kind of boundary drawing is a way of delegitimizing certain kinds of claims and privileging other kinds of claims. One of the most prominent recent examples is from the 1960s, when the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other African American ministers were using churches as places for civil rights organizing.

Jerry Falwell Sr. came out and said that this was not a legitimate thing for a pastor to be doing, that pastors should only be preaching the gospel from the pulpit, that these kinds of organizing things are political and shouldn’t be the concern of the church. Not too many years later, Falwell suddenly changed his mind. The one thing that really made him change his tune on this was that Bob Jones University, an evangelical university, was threatened with losing its federal funding because it didn’t allow interracial relationships. Evangelicals at the time were making very explicit claims defending the separation of races, and all of a sudden, that was a biblical issue.

What is biblical, what is political, often tends to be driven by self-interest. In the case of white Christian churches, I think it’s always appropriate to ask, “What kind of interest is that? Is it an interest that is privileging the position of white Americans over Americans of color?” And if it is, then it’s a straightforwardly white supremacist interest that’s being reflected in those distinctions.

|

| In his new book, Robert Jones argues that racist attitudes have become embedded in the DNA of white Christian identity over time and calls for an honest reckoning with the past | Courtesy of PRRI |

There still seems to be a lot of skepticism and resistance in white Christian spaces to words such as “social justice,” “white privilege” and “systemic racism.” At the same time, over the past few weeks, I’ve seen evangelical news sites emphasizing reconciliation, forgiveness, people coming together. Where do you think that comes from?

The easiest thing for white Christians to reach for is reconciliation. While I think that’s a laudable goal, if it’s reached for too quickly, I think it’s actually disingenuous. Too often, the formula for white Christians is white apology or lament plus Black forgiveness equals reconciliation. What’s missing in that equation is any conversation about justice and repair. If you’re a white Christian, heading straight for reconciliation is the quickest way to protect the status quo without doing the hard work and without really dealing with the past.

It’s surprising to me in some ways because if there’s anything I heard and that white Christian churches emphasize is this idea of repentance. But repentance, in the biblical sense of the word, is never just about apology. It’s about making things right. I think the real test of authenticity for white Christians who want to lament this past is whether they’re willing to walk through the valley of repair and justice in order to get to that destination of reconciliation or whether they want to skip that part of the journey.

How do you think white Christian churches have responded to George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter protests? Do you think the message is sticking, or are you seeing more evidence of what you call in the book the “white Christian shuffle”?

I called it the white Christian shuffle because there does tend to be this one step forward, two steps back movement. Particularly at moments like this one, where there’s a high social expectation that something will be said, something will be done, the question is whether it’s something authentic or something to just check the box and move on.

In my home state of Mississippi, the legislature finally voted to remove the Confederate battle flag from the state flag. Before that happened, the Mississippi Baptist Convention had a press conference and actually called on the legislature to do that. Now that’s a pretty big deal. But in my view, we can’t pretend we’ll get on the right side of the battles around symbols without dealing with the way white Christians built white supremacy into their theology and for so many years used Christian theology as a way to legitimize the worldview that put those monuments up in the first place.

What do you think it would it look like if white Christians began reckoning with that theology?

Part of what I hope the book will do is help white Christians tell a truer story about themselves. If it’s an older church, the questions are pretty obvious: “Where were we on the issue of civil rights? Where were we on the integration of our own congregation? Where are we now on the issue of mass incarceration?” Even for newer congregations that are predominantly white, it’s worth interrogating things as simple as, “Are we in an all-white suburb, and if so, why? Has there been a conversation about police killings of African Americans or about Black Lives Matter that isn’t just about the dangers of rioting but actually about the pain that African Americans are feeling at this moment?”

The second step after that reflection is to ask, “How can we be in community with African Americans and other people of color in our communities? How can we be allies on issues of racial justice?” Those conversations themselves will begin to challenge some of the ways in which white Christian theology has blinded white Christians to these issues.

A defensive reaction is a real temptation for white Christians at the moment. One of the biggest moves white Christians could make is to try to find some deep sense of humility and to listen and resist the urge to rebut and defend and to try to take in the witness that our African American brothers and sisters are trying to bring to white Christians.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

CORRECTION: Due to transcription errors, this article previously misstated the number of questions on Jones’ racism index, and how much more likely white Christians are to say the Confederate flag is a symbol of Southern pride rather than racism.