Introduction

I loved "The Shack" when I read it, and felt the movie that came out in March 2017 was very close to the original book's message. Frankly, its themes of the love of God, man's free will to love or unlove, and the tragedy of life when beset by sin, is one of those deep areas hard to understand but tells of God's love so plainly that it becomes the very substance which makes sense of all else in this thing called life. And it is the deep realization of God's love which the author, William P. Young, wished to express based upon a severe tragedy in his early life many years ago.

What I liked about the book is that Young took all the gnarly accusations of God and centered them into a fictious figure suffering an awful tragedy who began, in parable form, the long, hard process of working out what he believed was true and later, needed to correct, about the love of God in intricate dialogue and restorative venues. Which means watching the film will not be enough. It will require a thorough reading of Young's easily read (but deeply disturbing) book, The Shack, which must also be in order. And for its themes to truly sink in, a sharing of Mac's discoveries with fellow book club members.

To do this I've provided two reviews - one by Olson, who presents a list a questions for a reader or a book club to work through along with a companion volume. And secondly by Oord, who moves to the larger themes present in the book while presenting his own companion volume related to those larger themes.

Now I hesitate to advise forming "a bible study with church members" because so many in the evangelical church will misunderstand the theology behind the book (both Olson and Oord speak to this problem). For myself, it was when thinking/praying/meditating through The Shack that I discovered the paucity in my own thoughts about God, and then, over many years later, finally began to form my current blog/reference/website Relevancy22 to speak to this oversight and subsequent re-orientation of my thoughts about God.

Relizedly, throughout Relevancy22 the basic themes of The Shack can be found under dozens and dozens and dozens of topical headings if churchly direction is needed. But it would be best to begin on your own. If your journey is like mine, you'll find yourself re-thinking many of the church's errant teachings on God, His work and ways. For myself, The Shack's most basic message brought me back to the God I knew was there but hidden in the theology of the church thus creating conflict where it did not need to exist. This is the beauty of "Finding God" somewhere along life's journey. His/Her love comes to you from the most curious places to catch us back up to Himself/Herself even as Young learned and wished to present through the (autobiographical) novel's thoughtful arguments and penetrating lessons.

To do this I've provided two reviews - one by Olson, who presents a list a questions for a reader or a book club to work through along with a companion volume. And secondly by Oord, who moves to the larger themes present in the book while presenting his own companion volume related to those larger themes.

Now I hesitate to advise forming "a bible study with church members" because so many in the evangelical church will misunderstand the theology behind the book (both Olson and Oord speak to this problem). For myself, it was when thinking/praying/meditating through The Shack that I discovered the paucity in my own thoughts about God, and then, over many years later, finally began to form my current blog/reference/website Relevancy22 to speak to this oversight and subsequent re-orientation of my thoughts about God.

Relizedly, throughout Relevancy22 the basic themes of The Shack can be found under dozens and dozens and dozens of topical headings if churchly direction is needed. But it would be best to begin on your own. If your journey is like mine, you'll find yourself re-thinking many of the church's errant teachings on God, His work and ways. For myself, The Shack's most basic message brought me back to the God I knew was there but hidden in the theology of the church thus creating conflict where it did not need to exist. This is the beauty of "Finding God" somewhere along life's journey. His/Her love comes to you from the most curious places to catch us back up to Himself/Herself even as Young learned and wished to present through the (autobiographical) novel's thoughtful arguments and penetrating lessons.

Enjoy!

R.E. Slater

March 22, 2017

Finding God in “The Shack”

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogereolson/2017/03/finding-god-shack/

by Roger Olson

March 4, 2017

Comments

by Roger Olson

March 4, 2017

Comments

|

| Amazon link |

My movie viewers guide and theological movie review will be on InterVarsity Press’s web site in the near future. I will certainly notify my readers here when that is the case. For now I will not post those here but let IVP have them first.

In 2008 InterVarsity Press, one of my main publishers, asked me to write a theological commentary on the book The Shack: Where Tragedy Confronts Eternity (Windblown Media). I wrote it in less than a month and it was published as Finding God in “The Shack” in early 2009. It sold well and is still in print.

I hope you will buy a copy of my book if you have any interest in The Shack–either the book or the movie or both.

---

*Sidebar: The opinions expressed here are my own (or those of the guest writer); I do not speak for any other person, group or organization; nor do I imply that the opinions expressed here reflect those of any other person, group or organization unless I say so specifically. Before commenting read the entire post and the “Note to commenters” at its end.*

---

The movie lived up to my highest expectations and did not disappoint in any way. I have never seen a “Hollywood” movie (so not a Billy Graham film) that presented the gospel so clearly and unequivocally. That is not to endorse every sentence in the movie; it is only to say that if a person is able and willing to take it for what it (and the book) is–a parable–and not be put off by the imagery that person will hear the gospel in the movie.

Of course, were I a Calvinist, I might not think that. But, of course, I’m not, so when I say “the gospel” I mean the Arminian version of it. I do not know if Young considers himself an Arminian, but he cannot be a Calvinist. A major theme of the book and the movie is that evil and innocent suffering are not planned or willed by God even if God does permit them. They are the result of human misuse of free will. Free will plays a major role in the book and in the movie and the free will being referred to is non-compatibilist (i.e., it is power of contrary choice).

But the center of the movie is God’s goodness and love and our need to trust him in spite of what may happen to us or others.

A few years ago I met William Paul Young and heard him speak. His speech explained the autobiographical aspects of The Shack. He suffered a terrible event in his early life that could have made him question God’s goodness. Now, however, he wants everyone to know that the God of the Bible–Father, Son and Holy Spirit–is perfect, unconditional love who does not want any people to suffer unjustly and who wants everyone to be redeemed and has done everything to redeem everyone. Now, of course, it is up to us whether to be redeemed or not.

I highly recommend the movie, but I also urge people who see it to read the book. The book contains much more than the movie in terms of God explaining to the main character–“Mack”–God’s will and God’s ways. I also urge people who see the movie or read the book (or both) to get and read my book Finding God in “The Shack” which, again, is published by InterVarsity Press and is available from Amazon.

---

*Note to commenters: This blog is not a discussion board; please respond with a question or comment solely to me. If you do not share my evangelical Christian perspective (very broadly defined), feel free to ask a question for clarification, but know that this is not a space for debating incommensurate perspectives/worldviews. In any case, know that there is no guarantee that your question or comment will be posted by the moderator or answered by the writer. If you hope for your question or comment to appear here and be answered or responded to, make sure it is civil, respectful, and “on topic.” Do not comment if you have not read the entire post and do not misrepresent what it says. Keep any comment (including questions) to minimal length; do not post essays, sermons or testimonies here. Do not post links to internet sites here. This is a space for expressions of the blogger’s (or guest writers’) opinions and constructive dialogue among evangelical Christians (very broadly defined).

* * * * * * * * *

My Review of the Movie “The Shack”

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/rogereolson/2017/03/review-movie-shack/

by Roger Olson

March 16, 2017

Comments

Dear blog friends: Below you will find my review of the movie The Shack preceded by a “viewer guide” to the movie. I wrote these for InterVarsity Press which published my book Finding God in "The Shack'"in 2009. This viewer guide and review was first posted on their web site together with the information about my book.

May I just say that I am very disappointed in some evangelical Christians’ responses to both the book and the movie; in my opinion some of them are extremely shallow and dismissive. One that I have read even admitted that he will not view the movie or review it and then, on his blog, he does review it without seeing it. That seems very strange to me. He is the Calvinist blogger who labeled my book “Finding God in ‘The Shack'” a “weak effort” (back in 2009). I can only consider his “unreview” of a movie he has not seen and has no intention of seeing a weaker effort. If a person is going to talk about a movie he or she should at least see it first–unless it is notoriously pornographic, of course. Then just say that and move on. The Calvinist blogger to which I refer here says the movie “The Shack” makes the invisible (God) visible and, to him, seemingly, that is nearly blasphemous (not his words but mine). He does not seem to me to “get it” that this is just a parable full of imagery not to be taken literally.

Of course, I don’t expect Calvinists to like the theology of the movie, but I do expect them to at least view it before talking about it. This happened a few years ago when Rob Bell’s book “Love Wins” was being promoted–before it was published. Many Calvinists trashed the book before reading it. (I blogged about that.)

If you decide to respond to my comments here or to my review, please keep your comments civil and constructive (as always). If you disagree (or agree) give reasons. Keep your comment brief, please.

---

Viewer Guide to and Review of the Movie “The Shack”

by Roger E. Olson

Introduction: The movie “The Shack” (2016) is based on the 2007 book of the same title by William Paul Young. (It is published by Windblown Media and was written together with Wayne Jacobsen and Brad Cummings. The subtitle of the book is “Where Tragedy Meets Eternity.”) This movie viewer guide is to help people who see the movie think about its message. The movie, like the book, contains a very strong Christian theological message without being a sermon or lecture. Calling it a “Christian theological message” does not imply agreement with every point of the message. This writer believes it is always important especially for Christians to be biblically discerning when reading any book or watching any movie. Below are some questions to consider when viewing the movie. Following this viewer guide is a movie review which contains spoilers; you may not want to read it until after viewing the movie.

- If you read The Shack, how does the movie compare with the book—especially with regard to its message about God?

- What is the movie’s overall message about God—his nature and character?

- What is “the Great Sadness” referred to both in the book and movie? Whose sadness is it? What causes it—beyond a specific event?

- This question could be interpreted as belonging before the previous two questions, but here it is: "What is the overall theme and message of the movie?"

- How would you describe the main character’s (Mackenzie Phillips’s or “Mack’s”) religious life in the early part of the movie? How deep is it?

- Mack’s two daughters have theological questions; they raise them to him during their camping experience after viewing a waterfall and hearing Mack tell a legend about its origin. What are they really wrestling with in terms of the Bible’s story about God and Jesus? What do you think about Mack’s answer?

- The movie revolves around a tragic event. What does it do to Mack and his family? That is, how do they respond emotionally—especially in terms of their personal feelings and thoughts about their own roles in it and God’s?

- Does how God is portrayed in the movie bother you? Why or why not? Are you supposed to take it literally? (If not, how are you supposed to interpret the depiction of God?)

- Clearly, this movie, like the book it is based on, is intended to convince you to think a certain way about God, human existence in the world, tragedy, evil, the meaning of life. The following questions are guides to thinking with the movie. Implied in each question, without being stated explicitly, is the question “and what do you think about this and why?”

- According to the movie, what is the real cause of Mack’s Great Sadness? (In the book, anyway, his “Great Sadness” refers to more than an emotional feeling or state of mind; it refers to something deeper in the human condition.)

- The movie, like the book it is based on, contains a message about “religion.” What is that message?

- How do the divine characters in the movie “diagnose” Mack’s condition? What do they tell him are the underlying causes of his emotional and spiritual malaise? What do they ask him to do?

- The movie, like the book, contains and communicates a certain theological perspective about evil, tragedy, innocent suffering, humanity, and God. A pivotal point in all that seems to be a certain perspective on free will. What is it?

- According to the movie (and the book), what is the purpose of free will? What good does it serve? Why has God given it to humans? What are we supposed to do with it?

- Perhaps the most poignant scene in the movie, which is also in the book, is Mack’s confrontation with “Wisdom” in a cave. What message does Wisdom (an aspect of God) give Mack about himself?

- If we view the book and the movie as a kind of parable, whom does Mack represent?

- There is a word in philosophy and theology for any attempt to explain why there is evil and innocent suffering in a world created and ruled over by an all-good and all-powerful God: theodicy. What is the movie’s theodicy?

- How does the movie portray life after death?

- What is the “turning point” for Mack—in the story? At what point, and why, does “the Great Sadness” fall away?

Inevitably, viewers will have widely varying emotional responses to the story—depending partly, anyway, on their own experiences of tragedy. Setting emotion aside as much as possible, what do you think about the movie’s message—about God, the human condition in this world, tragedy, evil and innocent suffering, forgiveness, salvation, etc.?

---

A Theological Review of the Movie “The Shack”

by Roger E. Olson

Spoiler alert! If you have not seen the movie based on the book (of the same title) you may not want to read this review until you have seen the movie. It contains “dead giveaways” about the movie—including its ending. However, the movie adheres closely to the book, so if you’ve read the book but not yet seen the movie, you may want to read this movie review anyway.

The movie “The Shack” (2017) is the long-awaited film version of the book The Shack: Where Tragedy Confronts Eternity by William Paul Young (with Wayne Jacobsen and Brad Cummings) published in 2007 by Windblown Media. This writer/reviewer read the book when it was published and wrote a theological commentary on the book entitled Finding God in The Shack: Seeking Truth in a Story of Evil and Redemption published by InterVarsity Press in 2009. (Unbeknownst to this writer another book of the same main title was published by another publisher at almost the same time!) The book The Shack was causing much controversy among Christians—including some who did not even read it! This writer [myself] is an evangelical Christian theologian; my commentary was intended to guide fellow Christians in thinking about the book’s theological message. After my book was published I had the privilege of meeting William Paul Young and hearing him speak about The Shack. I spoke about The Shack and my book about that book in many churches during the years 2009-20012. Then the “hubbub” died down. Now, with the release of the long-awaited movie version, many Christians have a renewed interest in the story and its message. That is the purpose of this movie review: to express my own opinions about the movie and its message—as I did more fully in Finding God in The Shack.

---

I need to begin this review with some caveats. I am not any kind of expert on movies in general. Much of the time, I especially enjoy movies panned by movie critics and do not like movies that win praises from critics (and even “Oscars!”). I do not pretend to know anything about the artistic side of movies; I watch movies almost always only for entertainment. However, I sometimes also watch a movie for its message—especially about the human condition. I tend to think I see such messages embedded in movies (as in novels) that others miss. I tend to think, for example, that horror novelist Stephen King is a philosopher whose books and the movies based on them convey not-very-subtle messages about a worldview, about the meaning of life. Others do not always agree, but I am convinced of it.

The movie “The Shack” (which I put in quotation marks to distinguish it from the book whose title I put in italics—to distinguish them here) is clearly meant to convey a message and a very profound, if somewhat controversial, one. My review of the movie here will focus almost solely on that message; I claim no expertise about the artistic qualities of any movie including “The Shack.” (I will say that I enjoyed it very much, cried a little during it, thought the “cinematography”—whatever that is exactly!—was excellent and so was the acting. But what do I know about any of that?) So please do not look here for any expert commentary on the production values of “The Shack.”

---

My main question, and qualm, about the movie, before viewing it, was whether it would stick closely to the book—especially in terms of its theological message. I thought the theological message of the book was very interesting, thought-provoking, somewhat troubling in places, but overall theologically correct. In Finding God in the Shack I laid out my theological critique—both positive and negative—of the book’s message. There I emphasized that I thought it a parable and not a true story in the sense of description of real events that happened in time and space. I believed then, and still believe, that it is a theological message conveyed through a story [as a parable]. I believed that I could discern certain Christian theologians’ ideas in the story even though none are mentioned specifically.

I was very pleased at how closely the movie “stuck” to the story and to the author’s theological message. One specific question I had in mind as I began viewing the movie was whether, for example, the all-important chapter in The Shack entitled “Here Come Da Judge” (Chapter 11) would be included in the movie and, if so, how. To me, anyway, it is the central chapter of the book and the events it describes and the dialogue it contains—between “Sophia” and Mack contain the main point of the story. (I realize other readers and movie viewers will disagree, but that is still my opinion.) I was surprised and pleased by the way that scene was portrayed in the movie.

Frankly, I expected the movie, like so many that deal with theological questions and issues, would “dumb down” the message of The Shack. It didn’t. The basic message of the book comes through “loud and clear” in the movie—even if much of the dialogue in the book is omitted in the movie. As any reader of the book knows, much of it consists of rather lengthy conversations between Mack and God (portrayed as three persons such that Mack sometimes has separate conversations with them). I knew going into the movie that much of that dialogue would have to be deleted or at least condensed for time’s sake. It was. My personal opinion is that no one should see only the movie! Read the book for the rest of the story and especially for the theological content of the conversations which is the “meat” of the story.

Here I am going to limit my theological analysis and critique to the movie. For my whole theological response, please read Finding God in The Shack which is still in print by InterVarsity Press.

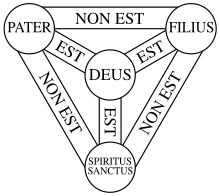

Here I am going to limit my theological analysis and critique to the movie. For my whole theological response, please read Finding God in The Shack which is still in print by InterVarsity Press.Unlike some viewers, perhaps, I will not take the imagery literally—especially the imagery of God. Of course God is not three separate personalities—one an African-American woman (“Papa”), another a Jewish man (Jesus), and the third a young Asian woman (Sarayu or the Holy Spirit). That is not the author’s or the movie’s intention and anyone who listens closely to the three can discern that these are only forms, manifestations, taken on the Father, Son and Holy Spirit for the purpose of helping Mack recover his faith in them. As a historical theologian, of course, I found myself, while watching the movie, saying—to myself—“Oh, that’s sound like tritheism” and later “Oh, that sounds like modalism.” (Tritheism and modalism are historical heresies about the Trinity.) But I do not think it’s fair to impose on the imagery or the movie itself—which is clearly intended as a parable—a literal [trinitarian] interpretation.

I believe the point of the story, both in the book and in the movie, will be missed by people who focus too much on the imagery and take it literally or allow it to get in the way of hearing the message.

---

The message of both the book and the movie, author Young’s message, comes through loud and clear in both if someone is willing to “get it” in spite of the possibly distracting imagery. What is that message? Well, I believe it is multifaceted but has a center. Let’s begin here with the center and work outward to the facets.

First, at its center, the story conveys the idea, promotes the belief, that God is unconditionally good and therefore can and should be trusted in spite of evil, tragedy and innocent suffering. There is an implicit “theodicy” at the center of the story. (As I explained in the viewer guide, a “theodicy” is any attempt to explain the consistency of an all-good, all-powerful God with evil, tragedy and innocent suffering in the world he created and rules over.) I suspect it may take two or more viewings of the movie, or a careful reading of the book combined with a viewing, to get it. But it is clear to me that the author and the makers of the movie are laying out for us, readers and viewers, a particular answer to the question “Why?”

The answer to that question comes through to me “loud and clear” in both the book and the movie and it will not be appreciated by “divine determinists”—those who believe God has “designed, ordained, and governs” everything that happens including sin, evil and innocent suffering. Many of them are called “Calvinists,” but Calvinists are not the only Christians who are divine determinists. To me, the center of the story of “The Shack” (and The Shack) is that sin, evil, tragedy and innocent suffering are not planned or rendered certain by God. They are foreknown by God, but they are not in any sense part of God’s will—except that he allows some of that to happen. (The book makes clear in a way I did not hear in the movie that God does intervene to stop much evil and innocent suffering but does not always for very good reasons unknown to us*.) Part of that center is that God is perfectly, unconditionally good and worthy of our trust in spite of our questions about evil and innocent suffering.

[*res - because when God created us in love, love grants to all creation full freedom to do and to will what it pleases. As such, God cannot overrule who He is (love) but must allow sin and evil "its day." The miracle is (or sovereign mystery is) that God works in the world His loving will to bring it into fellowship with Himself without disrupting or interfering with free will by overruling it. He might confront it, presage it, confound it, disquiet it, or thwart it in some way, and yet, God must be true to Himself and to His decree for creation to be fully free as much as it can be confined as it is within a sinful world. - re slater]

Much more is said about this in the book than in the movie; that is why everyone who sees the movie needs also to read the book. You cannot get the whole story, the whole message in all its fullness, from the movie alone.

---

So what does God say to Mack about evil, tragedy and innocent suffering? That it’s a fallen world we live in, corrupted in every part by human forgetfulness of God and even rebellion against God—all of which comes from misuse of free will—which is itself a good gift God gave to humans for freely receiving his love and having communion with him. Free will is itself not the center of the story; it is one of the peripheral points, a facet, of the story but clearly connected with the center. Sin, evil, corruption, tragedy, innocent suffering are not God’s perfect will; they are not intended or rendered certain by God. They are permitted by God for reasons God cannot explain to creatures in a way we can fully understand. God expects us to trust his goodness.

Another facet, peripheral point of the story, but also clearly connected with the center, is that God wants to redeem every creature, especially his human creatures of whom every one he is “especially fond.” However, redemption requires cooperation; God does not redeem—which means more than only “forgive”—by coercion. Mack has to kneel [in his heart willing] with Papa and confess his lack of forgiveness and say that he is willing to forgive his worst enemy. Only then can he be redeemed in the fullest sense possible in this life; only then can he enjoy life as it was meant to be enjoyed in communion with God.

If the story of “The Shack” (and The Shack) were a full blown systematic theology—which it is not intended to be!—surely the author would say much more about God, sin, salvation, the afterlife, etc. So that leaves many critics of the story guessing and some of them put the worst spin possible on it and shout “heresy!” in response to things they think are implied but not expressly stated in the story. For example, one might guess that the story implies “universalism”—belief that in the future all people will be saved. It does not say that; all it says is that God loves everyone equally and that Jesus died for all people equally so that all people can be saved.

Stepping aside from the movie, for a moment, however, and going back to the book, it does say that God has already forgiven everyone and done everything possible to redeem everyone. But both the book and the movie make abundantly clear that full redemption includes reconciled relationship and not only forgiveness. To forgive does not automatically establish relationship or reconciliation. Forgiveness, God says (in both the book and the movie) simply means taking your hands off the enemy’s throat. Again, imagery. One can assume it means not hating the person but being willing to have a reconciled relationship with them if they are willing.

I left the movie thinking many things at once (and with a few tears still in my eyes). Among them were that the movie leaves out much of the book that is at least peripherally important to the message and that it also leaves out the most controversial parts of the book. (Unless one takes the imagery of God literally in which case that’s perhaps the most controversial part of the book and the movie.) The book contains much more about free will and God’s will and why God allows evil and innocent suffering—although that is never fully explained because it is alleged to be beyond human comprehension.

I plan to see the movie again; I think it is a movie that really requires more than one viewing to get it all. I have read the book several times but may read it yet again. My response to both is that this is perhaps the best Christian fiction since C. S. Lewis’s novels and that the movie does not “dumb it down” as much as I feared it would. I do not think I have ever seen a “Hollywood-made” feature movie that as clearly conveys a profound Christian message without mixing it up with alien aspects or dumbing it down to the point of being simply insipid.