From Things to Events: Whitehead and the Materiality of Process

Abstract

The new materialist turn has refocused attention upon the shortcomings, both philosophical and scientific, of styles of thought that figure matter as an inert substance. According to the new materialists, the concept of matter must be rethought in order to account for its own vital capacities. Whilst largely sympathetic to this critique, this paper short-circuits the contemporary focus on matter through a sustained engagement with the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. For Whitehead, the concept of matter represents a failure to think process on its own terms; that is, without invoking an underlying permanence. Whitehead's philosophy is thus of great significance to contemporary debates because it questions what it means to speak of agency, relation, and vitality in a world composed of processual events rather than things. In doing so, it sharpens our sensitivities towards nonhuman processes of existential change. Exploiting this capacity to shift our attention, the paper explores the implications of Whitehead's philosophy by staging an encounter with a peculiar experimental object. By unpacking the key concepts of ‘occasion’, ‘prehension’, and ‘concrescence’, the object in question is gradually transformed from discrete thing to processual event, with a number of consequences for materialist thought.

IV

Emergentist Panpsychism

by Philip Clayton

TRANSCRIPT

Panpsychism is not like pregnancy. A woman either is or is not pregnant. In such cases more

generally, either x or not-x. By contrast, you are not either warm or not warm, tall or not tall,

smart or not smart. You can be more or less slow, more or less prompt, more or less witty. The

discussion of panpsychism is changed in important and fruitful ways when we recognize that the

topic is better understood in the latter way than in the former.

At first glance, the panpsychism debate appears to be a question of all or nothing, just as the thief

either takes all William’s money or he doesn’t. But I suggest that we need to think our way

beyond this way of approaching panpsychism. Particularly in the context of panentheism, our

discussions should become more complex than, say, the thesis that all levels of evolution can be

summarized under the heading of pan-psyche or, following David Ray Griffin, pan-experience.

Instead, I will argue, the discussion of God, evolution, and psyche needs to be expanded to

include the full variety of qualities, including awareness, intention, goal-directed behavior,

mental representation, cognition, and consciousness. Clearly this shift has implications for

understanding the nature and scope of metaphysics and theology, a topic to which I shall return

at the end of this short paper.

Three things will happen when we return to the panpsychism question after this analysis. The

first, I hope, is that it will help to deepen the discussions of John Cobb’s work, and of

Whitehead’s, during out two days together. The other two reflect my deep interest in biological

evolution and theology. We should be able to specify the sense in which evolution produces

qualities that were not actually already in the parts. And, finally, we should be able to reach a

more complex understanding of the relevance of panentheism to questions of the evolution of

consciousness, and hence a more complex understanding of the Divine itself. The upshot is a

more limited affirmation of panpsychism, in contrast to the more “maximal” affirmation of the

existence of psyche in all things, or all things as psyche.

The qualities that we call mental or proto-mental are extremely diverse. Because the differences

are greater than is often acknowledged, in this paper I will be defending a minimal or

“gradualist” panpsychism rather than traditional or “maximal” panpsychism. It will not have

escaped you that minimal and maximal are terms on a quantitative scale rather than expressions

of a forced either/or choice. Panpsychism in this more minimal form, I will argue, is the more

2

compelling view; and the quantitative nature of the discussion should help us to more fully

nuance our discussion during the discussion.

First, though, let’s get a full sense of the range of questions raised by this topic. If we are going

to make progress in the areas where stalemates usually arise in discussions between

Whiteheadians and emergentists, we will need to understand the questions that need to be raised

… and the questions that are less productive.

Clarifying the questions

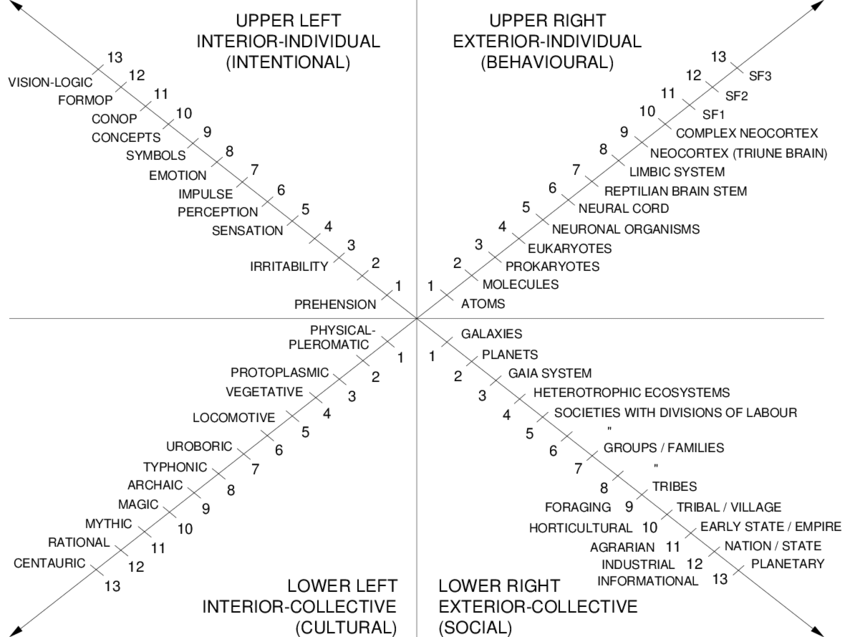

(1) Mind and mental entities. Of course, many philosophers today doubt whether mentality as

such even exists or, more accurately, whether mental states or qualia have a primary rather than

derivative existence. Most people here, I assume, are well aware of this debate, and some engage

in it professionally. But the major advocates of physicalism are not present here (as far as I

know); in the audience I don’t see Wolf Singer, Francis Crick, or Dan Dennett. Whether

anything mental exists may be a major debate, but I don’t think it’s the topic de jour.

I thus recommend that we begin instead with the assumption that some mental attributes or

things exist and exercise causality qua mental. (I will problematize “the mental” in a moment.)

Mentality is not merely an epiphenomenon. It is not merely supervenient on physical states, nor

is it merely a weakly emergent property of physical matter/energy, where all true causal forces

reside.

In short, we have more important fish to fry than reductionism. Leaving aside reductionism at the

start will allow us to focus in on a different set of questions. For example: Does finite mentality

arise at some point in cosmic evolution, such that it was not actually present at one point in time

and then later was? If mentality is emergent, then must it always be linked to something physical,

say a body? Do separate mental units, say souls, exist, or are they just multiple manifestations of

one mental reality (call it God)? Skrbana puts it nicely:

The central issue here is whether we speak of such mind as “mind of single universal”

(God, the Absolute, the World Soul, and so on) or of mind as attributable to each thing in

itself (of each object’s possessing its own unique, individual mind). The former view

would be a monist concept of mind, the latter a pluralist concept.1

Whitehead’s famous notion of actual entities2 moves in the direction of radical pluralism.

Assume for the moment that he is right and that an extremely large number of actual entities

(AEs) exist. This requires us to think of each such moment of creative becoming as a distinct

entity or occasion, existing on its own. Of course, one can be a radical pluralist in this way and

3

still hold that AEs are so interdependent that they are internally related (as I argued in a recent

paper). That would mean a radical pluralism of psyches.

Does the world contain anything that is non-mental, such as purely physical objects? I’d

encourage you to resist this either/or frame; it leads too quickly to a simple syllogism:

Some mental things exist.

Nothing exists that is purely physical.

Hence, all things are mental things.

I will suggest that the more interesting discussion is of the varieties of mentality or “psychisms.”

Interesting nuances of “psychism” surface when one explores options such as limited

panpsychism, emergentist panpsychism, or the panpsychism of potentiality and actuality, as I do

below. These nuances cause us to reflect on the differences, and thus on the status of the unifying

concepts.

To proceed in this way is to hypothesize that “the mental” is not an either/or quality, such that an

entity either is mental (has the attribute of mentality) or isn’t. (For now I use “a mental entity”

and “an entity that has mentality” interchangeably.) It is more fruitful to ask, “To what extent,

and in what sense, is this entity mental?”

(2) Panentheism. A series of questions arise at the intersection of panpsychism and panentheism.

Some represent difficult challenges for classical panpsychism.

If there is a plurality of mental entities, how is God related to each one? For Whitehead, each

actual entity is an ultimate, not more dependent on God than God is on it. But actual entities

could be dependent on God in a stronger way, existing only through the continuing will of God;

or they could be real individual expressions of a single divine Spirit (this is the view of the

Indian philosopher Ramanuja); or, following Spinoza, what we call individuals might merely be

ways that the one divine substance is manifested in a particular time or place ― modes of the

One. How would one decide between these options?

Panentheism might also raise some critical questions for classical (pre-Whiteheadian)

panpsychism. What is God’s relationship to finite mental entities if they are really present “all

the way down”? If God lures even an electron, what does God lure it to do? Or does theological

panpsychism instead support monism? That would mean that the psyches that seem to be in all

things are actually just one psyche: the one mind of God, or Nous in Plotinus’s sense. For that

matter, how would one distinguish finite “natural” mentality from infinite divine mentality? Can

the one be within the other without compromising the integrity of either? Do classical

4

panpsychisms maintain that it’s the God question that supports the dichotomy either everything

is mental or nothing is mental and, if so, why?

In contrast, a gradualist panpsychism begins with the question To what extent, and in what sense,

is a given entity mental? Formulating this question, one immediately recognizes that the

relationships between panpsychism and panentheism are rather more complex than one might

have thought. There are no simple entailments: one can be a panpsychist without being a

panentheist, for example if one is a pantheist. Conversely, one can be a panentheist without being

a panpsychist, for example if one holds that the world is God’s (material) body. Above all,

gradualist panpsychism shifts the conversation in that one must now ask about the relationship

between the panentheistic God and the whole history of emergent mentality.

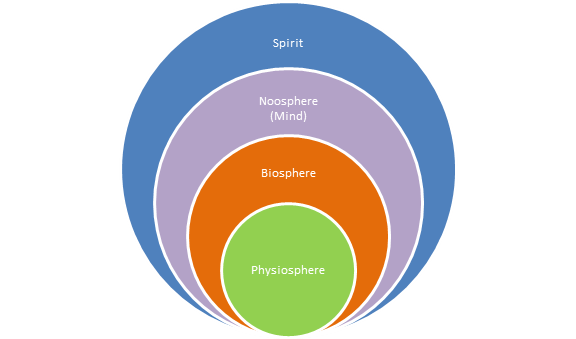

Emergent Mentality

Gradualist panpsychism seeks a theory of consciousness that is consonant with the results and

the methods of the sciences as well as with human phenomenal experience. Let’s call this a

theory of emergent mentality. It’s the view that the particles and physical states of (say)

macrophysics and physical chemistry do not manifest an actual mentality; they do not have

intentions, for example. The first self-reproducing cell, by contrast, does have a primitive

awareness of its environment. Increasing complexity across biological evolution brings more and

more complex awareness, with human consciousness being the most advanced form of

awareness that we have yet discovered.

Emergent mentality as I use the term stands in contrast to Whitehead’s panpsychism or

“panexperientialism.” Famously, Whitehead holds that all units of reality are occasions of

creative becoming. Each actual (as opposed to merely potential) entity is thus its own center of

experience. If given only a single argument to defend this view, Whiteheadian panpsychists will

generally argue that mentality cannot come from something that is non-mental. But

Whiteheadians are by no means the only philosophers who object to gradualist theories of

mentality. All dualists do, as well as many neuroscientists who are drawn toward exclusively

material explanations of thought and consciousness. So let’s call this particular critique the “no

mind from matter” (NMfM) Objection. Thomas Nagel sometimes expresses a similar intuition as

fundamental or “schematic” for him: “In its schematic, pre-Socratic way, this sort of monism

attempts to recognize the mental as a physically irreducible part of reality.”3 I will argue that this

intuition does not stand up to closer examination, at least not in this particular (non-theistic)

form.

Finally, I do not think that theism as such falsifies one option and verifies the other. It is not

inconsistent for advocates of most (but not all) forms of theism to affirm either Whiteheadian

5

panpsychism or emergent mentality. But I do think that setting panentheism in dialogue with

contemporary philosophy and science supports gradual over maximal panpsychism.

The argument proceeds in four steps.

(1) Evolutionary mentality and emergentist panpsychism

The evolutionary evidence suggests the emergence of the various phenomena that we call

mentality, a position often called emergentist panpsychism. Of the various forms of limited or

gradualist panpsychism, this position is in my view the most convincing. Once again, it starts by

challenging the assumption that all existing things either are or are not centers of experience.

Limiting or conditioning the “pan” in panpsychism is an important part of making this case.

Thomas Nagel is a famous anti-emergentist panpsychist. He argues, for example:

The implausibility of the reductive program that is needed to defend the completeness of

… naturalism provides a reason for trying to think of alternatives—alternatives that make

mind, meaning, and value as fundamental as matter and space-time in an account of what

it. The fundamental elements of physics and chemistry have been inferred to explain the

behavior of the inanimate world. Something more is needed to explain how there can be

conscious, thinking creatures whose bodies and brains are composed of those elements.

… Everything, living or not, is constituted from elements having a nature that is both

physical and nonphysical—that is, capable of combining into mental wholes. So this

reductive account can also be described as a form of panpsychism.4

Nagel and I agree in opposing the reduction to physicalism but disagree concerning when this

“something more” is needed. He thinks that, in order to beat physicalism, mind must be

fundamental to all things, whereas I argue that the first time it becomes fundamental is in the role

it must play to explain self-reproducing cells. From cells on we no longer disagree.

For the emergentist panpsychist, “mind” ― in the minimal form of awareness and goal-directed

behavior ― is first discernible with the emergence of self-reproducing life; as a concept it only

begins to play a role after that. From the birth of cellular agents, the two positions walk side by

side. For example, both Godehard Brüntrup5 and I agree that unicellular organisms possess a

rudimentary form of awareness. This awareness is a matter of life and death to the cell. After all,

cells can live and reproduce, or they can die. From an evolutionary point of view, they have an

interest in living. To move up a glucose gradient and receive more nutrition is in the interest of a

unicellular organism; it is “good.” To move toward a toxin is “bad.” The cell’s (chemically

mediated) awareness of its environment, which differentiates between the two, is of its very

essence.

6

It’s fascinating to trace the evolutionary process from primitive awareness and goal-directed

behavior at the birth of the biosphere to the most complex conscious cognition and subjective

experiences. Note that, once a certain threshhold is passed, the anti-emergentist panpsychist

appears to be as willing as the emergentist panpsychist to affirm the emergence of ever more

complex mental phenomena.

(2) Mind in potentia

The more plausible the transition from potential to actual mentality becomes, the more the

NMfM Objection is undercut. Although in the end my argument will require a theological

dimension, the first step of the argument can be made without it.

Although each cell is aware, each can potentially become part of (say) a human being, a being

with the attribute of consciousness. So the cell is potentially conscious if the right circumstances

occur; specifically, it is potentially conscious in the sense that it can become part of a whole to

which we attribute consciousness (say a human person).

This topic raises some complex dilemmas concerning location and part/whole relations. Not

every property of a whole is a property of its parts (redness), nor is every property of a part also a

property of the whole (weighing less than one kilo). But some properties of parts are also

properties of the whole (having some weight), some properties of a whole may also be properties

of its parts (if the whole orchestra is in tune, then each instrument is in tune). Regarding location,

it’s easier to say “Beth is conscious, but consciousness is not the kind of property that has a

location.” Surely consciousness does not have a location in the same way that her hat does; still,

if Beth is in California, we wouldn’t say that her consciousness resides in Tokyo. Is Beth’s

consciousness located in each neuron of her brain, or in her brain as a whole, in her body as a

whole, or in her personhood (whatever that is)? It seems most adequate to say that Beth’s

consciousness is present in Beth as a whole. Clearly, these philosophy of mind questions are

relevant to panentheism as well.

Now consider an analogy. The cell as a whole is aware. And the actual chemical components of

a given cell had the potential to become part of that cell. Take for example one of the cytosine

molecules (chemical formula C4H5N3O) that pairs with guanine to make up a rung in the DNA

double helix. This particular molecule is potentially aware in the sense that, if the right

circumstances occur, it becomes part of a whole cell to which we attribute awareness.

The analogy does two things. It treats both consciousness and awareness as whole-part

relationships, which seems right. And it treats consciousness and awareness as existing in two

forms: potential and actual. If the analogy holds, it allows us to say that consciousness already

7

exists in potentia, in the parts that compose a conscious person, and that, analogously, awareness

exists in potentia in the parts that compose a cell.

Now consider the NMfM Objection to emergent mentality, viz., that you can’t get consciousness

from something that is not conscious. For a Cartesian, this is right; res cogitans and res extensa

are dichotomous. For Descartes one can never emerge from the other because he presupposes

from the start that no potential for this transition exists. By contrast, Western philosophy and

science offer a number of ways of understanding the transition from potential to actual. We could

explore science-based analogies such as superposition, as in the “collapse” of the (probabilistic)

Schrödinger wave equation to a particular macrophysical state.

6 More broadly, you are already

aware that Western metaphysics offers a rich legacy of ways to conceive the transition from

potential to actual, for example in metaphysical systems inspired by Aristotle and in the

dialectical philosophies of the German Idealists. These achievements offer rich resources for

conceptualizing the transition from potentially aware to actually aware. To the extent that the

transition becomes comprehensible, the NMfM Objection is answered.

(3) Gradualist panentheistic panpsychism

(1) God is a mental entity, the source of all mentality

(2) Everything is in God

(3) So all entities are mental entities.

I argue in a recent article that the affirmation everything is in God is not sufficient to demarcate

panentheism from various forms of classical theism.7 Still, a position would surely not count as

panentheism if it does not affirm (2) in some sense. For its part, (1) is an affirmation about God

that is held in one form or another across most of the history of theology. For example, even if

God has a body, God is not simply a material being. Applied to God, “mental entity” could mean

a variety of different things: has (or essentially has) mental attributes, or is solely mental in the

sense of having no physical attributes, or is the source of all mentality, or is mentality as such,

etc. If (3) then follows, then from panentheism one can infer panpsychism.

Looking more closely at the alleged syllogism, one recognizes two things. First, its inference is

not valid.8 Perhaps if (2) affirmed that “Everything is God,” the conclusion would follow. But

that would be pantheism, not panentheism.

The argument also begs for a closer analysis of what is meant by mental entity. Given the

imprecision of the term, it can only serve as a rough label for a set of different concepts. Thus

Uwe Meixner writes in the Brüntrup and Jaskola collection cited above, “The immediate

consequence of this idea [panentheism] is that everything is in God (qua being in this total

experience, which at the same time is the totality of all experiences), whether as an experience,

8

as a subject of experience, or as an object of experience.”9 Process theologians, influenced by

Hartshorne, and then later by John Cobb, have explored these options in some detail. For

example, Whitehead’s “objective immortality” affirms that only the outcome of creative activity

(concrescence) is in God, whereas Marjorie Suchocki’s “subjective immortality” places the

actual entity in its very becoming within God.

The ambiguity of “mental entity” and of the “in” implied by panentheism makes it impossible to

draw direct consequences from panentheism to panpsychism in the full or “maximal” sense.10

Maximal panpsychism is not entailed, for example, if the panentheistic “in” is interpreted as the

spatial “in,” nor if it is the finite “in” the infinite. Unless and until it is shown that the “in” of

panentheism requires every existing entity to be a mental entity (to have mentality as one of its

own properties), one is not compelled to affirm maximal panpsychism. Of course, one can

attempt to defend that view on other grounds. But panentheism alone will not get one there.

Panentheism is helpful to the emergentist panpsychist, however. Even a minimal (panen)theism

affirms divine creative intent and a continuing lure toward a telos that is consistent with the

divine nature. Since the divide nature is or includes mentality, one has reason to expect that the

telos is or includes mentality as well. That created mentality may not be instantiated at the time

of the big bang; it may be the product of a universe continually lured toward the divine nature.

This result is consistent with work on the stages of cosmic evolution in the science-and-theology

discussion: the mathematical laws of astrophysics that reflect the constancy of God; the selforganizing patterns of biochemistry; the emergence of awareness and goal-oriented behavior at

the dawn of the biosphere; and the gradual development of the capacity to know and worship

God. Gradualist panentheistic panpsychism becomes the affirmation that God lures creation

from “potentially aware” to “actually aware” in ways that preserve both the transcendence and

the immanence of God.

(4) “God in all things” and the ground of mentality

We have discussed all things in God; now we must turn to the second “in” of panentheism: God

in all things.

(1) God is in all things.

(2) Wherever God present, mentality is present.

(3) Mentality is present in all things.

Proposition (1) restates a major biblical theme, such as Acts 17:29, where Paul speaks of God as

the one “in whom we live and move and have our being.” The same assertion is present in most

forms of Western theism. Benjamin Göcke and others have shown that (1) is not distinctive to

panentheism.11 Yet “God in all things” does express one of the two “in’s” that even a minimal

9

form of panentheism must affirm. Likewise, (2) should be non-controversial for theists. (3) thus

represents a second entailment from panentheism to at least a minimal form of panpsychism.

Again, though, we must ask: panpsychism in what sense?

Skrbina puts the point nicely:

There is a lingering and problematic sense in which Christian theology does allow for a

weak form of panpsychism. If God is omnipresent, then he is obviously “in” all things;

this points toward panentheism. If a portion of God is in a thing, and this portion assumes

any sense of independent individuality, then this could qualify as a “monistic

panpsychism.”12

Skrbina recognizes that “panentheism can be confused with panpsychism.” As we saw in the

previous section, the two cannot be identified, but the former does imply, at minimum, an

evolutionary sense of the latter. But could it be that panentheism implies panpsychism in a

stronger sense than I have granted here? For example, Skrbina notes, “On the traditional view,

God is omnipresent. If God represents spirit or mind, then all things can be said to contain

mind—the mind of God.”13 The traditional doctrine of omnipresence by itself does not entail

panpsychism, since God could be merely present to. But if God as mental actually exists within

all things, as panentheists affirm, then wouldn’t a form of panpsychism stronger than emergentist

panpsychism follow ― a panpsychism closer to the process version?

In order to respond to this final objection to a gradualist panpsychism, it is helpful to take a

closer look at the work of Thomas Nagel. Nagel is a non-theist who affirms a fundamental role

for mind: “Mind, as a development of life, must be included as the most recent stage of this long

cosmological history, and its appearance, I believe, casts its shadow back over the entire process

and the constituents and principles on which the process depends.”14

Nagel holds that the gradual appearance of mind across cosmological history requires one to

affirm that mind was present in the universe from the beginning as a fundamental principle,

analogous to the way that physicists affirm that physical laws and mass/energy were present

from the beginning. He argues:

So if mind is a product of biological evolution—if organisms with mental life are not

miraculous anomalies but an integral part of nature—then biology cannot be a purely

physical science. The possibility opens up of a pervasive conception of the natural order

very different from materialism—one that makes mind central, rather than a side effect of

physical law.15

10

Examining this passage, however, one recognizes an important disanalogy between physics and

biology. It’s true that physicists have to postulate that the fundamental physical particles and

forces were present from the big bang, since they are essential for explaining even the first

micro-seconds of cosmic history.16 But one does not have to postulate the presence of mental

entities, or properties such as awareness, in the same way. One might want to affirm that mind is

“central” in the first million years of cosmic history for other reasons, but there are no empirical

reasons for doing so; it’s not a postulate that one actually needs at that point.

Recall the “no mind from matter” (NMfM) Objection. Anti-emergentists such as Nagel and Cobb

argue that, if we don’t postulate the presence of mind from the beginning, it can’t play a role

later on, for example in biological or psychological explanations. That might have been true,

emergentists respond, if the only options philosophy had were x exists or x does not exist. In fact,

though, the resources available to us include powerful theories of the both/and, dialectical

accounts of the changing proportions of mental and non-mental. The traditions stemming from

Aristotle, for instance, offer compelling ways to think about transitions from potential to actual,

and thus about the status of potentials, that is, things that exist in potentia. To name just one

recent example, the scientist Stuart Kauffman ascribes to “the adjacent possible” a quasi-causal

role in quantum physics and a role as a formal or structural cause in biological evolution.17

These conceptual resources, I suggest, deflate the power of the either/or assumption on which the

NMfM Objection rests.

Once we are able to set the NMfM Objection aside, an important area of shared agreement

becomes visible, namely: I believe we may be able to agree that some ground for the gradual

evolution of mentality must exist. Here we can affirm Nagel’s contention: “We ourselves are

large-scale, complex instances of something both objectively physical from outside and

subjectively mental from the inside. Perhaps the basis for this identity pervades the world.”18

Interestingly, when Nagel begins to speak of this “basis,” he cannot avoid theological language:

Or maybe, as Colin McGinn (1989) famously argued, human beings are constitutively

incapable of grasping the nature of the properties underlying consciousness; it could

nonetheless be that the emergence of consciousness from non-consciousness is

intelligible to God if not to us.19

More precisely, Nagel might have written, “the emergence of consciousness from nonconsciousness is intelligible to God … and intelligible to us if we include, however

hypothetically, the notion of God and divine creation.” Many panentheists hold that divine mind

precedes the creation of the universe, so that creation manifests divine intention and other

features of God’s nature. The telos of God’s ongoing creative act, in the words of the

Westminster Shorter Catechism formulates it: “Man's chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy

him forever.” This goal does not require that mentality have been actually present in created

11

beings from the first moment of cosmic history. But it does require that it have been present in

potentia. That condition is met because the universe as a whole reflects the mind of its creator

and the divine intent that mentality would eventually emerge and be manifested in the created

world.

Conclusion

Thinking back over the argument, one begins to recognize that this particular debate represents

one particular instance of a much broader project: reflecting one’s way toward sophisticated

responses that address core theological commitments on the one hand and the best of

contemporary philosophy and science on the other. Success is impossible without participants

who are willing to keep the doors open in both directions. The Richard Dawkinses and Dan

Dennetts on the one side construe the natural world in such a way that mentality, and thus God,

cannot play a fundamental role. Strong advocates of the separateness of God, Cartesian dualism,

or interventionist divine action close down the discussion from the other side. Process

panpsychists and emergentist panpsychists do not need to make either of these two mistakes.

We are familiar with theologians willing to do the hard work in philosophy and science to open

up the discussion, but equally important are scientists such as Stuart Kauffman and secular

philosophers such as Thomas Nagel. In the following passage, note how deeply the non-theist

Nagel enters into the conceptual world of theism:

My preference for an immanent, natural explanation is congruent with my atheism. But

even a theist who believes God is ultimately responsible for the appearance of conscious

life could maintain that this happens as part of a natural order that is created by God, but

does not require further divine intervention. A theist not committed to dualism in the

philosophy of mind could suppose the natural possibility of conscious organisms

composed, perhaps supplemented by laws of psychophysical emergence. To make the

possibility of conscious life a consequence of the natural order created by God while

ascribing its actuality to subsequent divine intervention would then seem an arbitrary

complication. Some form of teleological naturalism should for these reasons seem no less

credible than an interventionist explanation, even to those who believe that God is

ultimately responsible for everything.20

Nagel’s words here beautifully reflect the goal of this paper, and in some ways also its outcome.

I have embraced teleological naturalism by eschewing mind/body dualisms and affirming

mentality only where it is observable and plays some explanatory role. At the same time, I have

pursued the questions from my standpoint as a panentheist. These two commitments required me

to find a version of emergent mentality compatible with the double “in” of panentheism: all

things in God and God in all things. The requirements of theology, philosophy, and science are

12

best met, I argued, by a gradualist panpsychism that affirms the actuality of divine mind, the

potentiality of mentality from the moment of creation, and the actual emergence of mentality

over the course of evolution.21

Endnotes

1 David Skrbina, Panpsychism in the West (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005), 21. 2 A.N. Whitehead, Process and Reality, corrected ed. (New York: Free Press, 1978). 3 Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly

False (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 62. 4 Nagel, 20, 57.

5 Godehard Brüntrup and Ludwig Jaskolla, eds., Panpsychism: Contemporary Perspectives (New York, NY: Oxford

University Press, 2017),

6 Quantum physics offers an empirical basis for thinking about the concepts of the actual and the possible or

potential. “Potentially aware” and “actually aware” can exist in a way that is analogous to a quantum superposition.

(This is an argument that I developed in conversation with Brüntrup in conversation in October.) We know that the

Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics allows for states that are superpositions of actual and possible. In the

famous thought experiment known as Schrödinger’s cat, the cat exists in a state of superposition of dead::alive until

a measurement causes the collapse of the wave function into either dead cat or alive cat. A so-called quantum

computer (if one can be constructed) would be powerful because each bit (“qubit”) could manifest not two but three

different states: on, off, or indeterminate. So far physicists have been able to prepare up to 50 individual atoms in

individual “traps.” These matrices extend quantum potentials far beyond the scale at which they normally occur. 7 Philip Clayton, “Prospects for Panentheism as Research Program,” European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 11,

No 1 (2019): 1-18. 8 To succeed, (2) would need to read “Everything is God.” (And even then there are problems, as we can learn from

Shankara’s philosophy.) Panentheism is distinct from pantheism precisely because it does not make this assertion. 9 Uwe Meixner, “Idealism and Panpsychism,” in Panpsychism: Contemporary Perspectives, eds. Godehard

Brüntrump and Ludwig Jaskola (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 399.

10 The question of whether panpsychism is helpful to the panentheist is an interesting one, although I will not have

the chance to develop this argument fully here. Robert C. Whittmore maintains that panpsychism can become

panentheism or, even more strongly, that panpsychism may imply or entail panentheism. He uses a passage from

John Fisk:

Panpsychism becomes panentheism in the realization that this “Life” manifest in all nature is “only a

specialized form of the Universal Life,” which is that “eternal God indwelling in the universe, in whom we

live and move and have our being.” For if, as noted earlier, God cannot be conceived as something outside

the universe (as maintained in anthropomorphic theism), and if, as has been shown, we cannot identify Him

or It with the universe phenomenally manifest (since this would be pantheism), then it must be that the one

(theistic) alternative remaining is the truth: the universe is (as panentheism teaches) inside God! (John Fisk,

quoted in Robert C. Whittemore, Makers of the American Mind: Three Centuries of American Thought and

Thinkers [Apollo Editions, 1964], 303.)

Whittemore is right to note the inference from panpsychism to panentheism, adding only that the inference does not

require maximal panpsychism; it works just as well from the standpoint of maximal panpsychism.

11 See Clayton, “Prospects for Panentheism as Research Program.” 12 Skrbina, 274 n. 24. 13 David Skrbina, Panpsychism in the West (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005), 21. 14 Nagel, 8. This is part of his non-emergence thesis, that is, his claim that there are no truly emergent properties of

complex systems.

15 Nagel, 15. 16 See Stephen Weinberg, The First Three Minutes (New York: Basic Books, 1977).

13

17 See Stuart A. Kauffman, Humanity in a Creative Universe (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2016). 18 Nagel, 42. 19 Philip Goff, “Panpsychism,” Stanford Journal of Philosophy (July 2017),

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/panpsychism/#AntiEmerArgu. 20 Nagel, 95. 21 As in my October paper for the Stuttgart conference, I am again grateful to Andrew M. Davis, who has worked as

my research assistant on this paper. Our conversations together were important in formulating the key questions of

this paper, and some of its key ideas emerged in discussions with him. (This is not to say that Mr. Davis agrees with

the final thesis of the paper, however.) Every author knows the importance of the formative discussions that come

just before writing, and it is a particular pleasure when these discussions can occur with one’s graduate student.