Beverly is a professional genealogist and author with a background in both public education and religious education. She combines these qualifications to present a picture of the influences and religious contributions of women in America with regard to Christian denominational history.

What subjects will be covered in this website?

- How did women act as Christian leaders throughout American history?

- Who were these women?

- What family circumstances precipitated the actions of these women?

- Were their contributions significant?

- Reflecting upon the personalities and activities of these women, what might one learn from their examples?

While this web site can only point out a handful of the women who have contributed to American Christianity, and only briefly at that, it is my hope that readers will seek out additional information about persons to whom I can only provide an introduction.

Early in the 21st Century, society will add the names of numerous Christian women leaders from the closing decades of the 20th Century. One ponders what the nature of women's contributions to Christian society should be in the century just now lying before us.

Can the content of this website be copied?

This is copyrighted material. If you include portions of the information contained here in your own compiled genealogy, history sketches or school papers, you should cite as your reference: Beverly Whitaker. "American Women in Christian Denominational History." Kansas City, Missouri: Genealogy Tutor, 1999, as summarized on Internet web page: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~gentutor/women.html

Using this script as an oral presentation requires written permission.. Send your request to Beverly Whitaker by e-mail: gentutor@yahoo.com Or mail your request to Beverly Whitaker, 4318 N. Baltimore, Kansas City, MO, enclosing a self-addressed stamped envelope for response. State the GROUP and CITY for whom the presentation is to be made, along with the date.

You have permission to place a link to this web site on your own web page.

I am not your source for answers to specific questions, either about specific women or concerning denominational history.

I don't have the time to do the considerable research necessary to provide responses to such questions.

A general bibliography of references is included at the end of this commentary.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE EARLY COLONIAL PERIOD

THE MIDDLE 1700s

RELIGIOUS AWAKENING IN THE 1800s

WOMEN REFORMERS OF THE 19TH CENTURY

AUTHORS AND EDITORS

MISSIONARIES, PREACHERS, EVANGELISTS

ROMAN CATHOLIC WOMEN OF NOTE

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Until recent times, women's history was largely ignored and sometimes deliberately suppressed. So we have been robbed of the full inheritance of our foremothers. Our knowledge of their achievements has been limited. Our acquaintance with American churchwomen is likewise scanty, but research leads to a knowledge of some remarkable women of faith.

What caused women to become involved with religious and social causes in America? From the earliest days to the present, women have looked around and have seen much needing action. Often they wished the churches would take more initiative; frequently they chose not to wait for the church to take the lead and instead took on responsibility as individuals to address the needs they identified. History may tell us that as these women plunged themselves into Christian causes, they began also to establish their rights and roles in the church.

THE EARLY COLONIAL PERIOD

To catch a glimpse of some of these remarkable women is inspiring.

Let's look first at the early colonial period.

Anne Marbury Hutchinson was the first person to strongly challenge the rigidity of the Puritan religion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Banished for her independence, she stands as a symbol of religious freedom and personal courage. Anne was the daughter of an Anglican priest back in England. During her years as a young wife and mother of 12 children, she became a disciple of the Anglican minister John Cotton. When he was forced out of England for his reinterpretation of the Puritan doctrine, Anne and her family followed him to Boston (1634). There, she established weekly meetings of women to discuss the sermon and to expound upon her own opinions. But in 1637 when her chief opponent John Winthrop was elected governor of the colony, she was brought to trial for her views. They banished her from Massachusetts. She went first to Rhode Island, and then, after she was widowed, she went to New York. In 1643, she and all her children but one were massacred by Indians.

Mary Dyer, a bold Quaker, was banished on three occasions from the Puritan colony of Massachusetts. Because she kept returning, the townspeople finally silenced her by hanging at Boston Common in 1660. But before her death, she stood before the authorities of Massachuseets Bay and demanded religious tolerance, saying, "I am a living testimony for (the Quakers) and the Lord, that he hath blest them and sent them unto you; therefore be not fighting against God, but let my council and request be accepted with you to repeal all such laws that the Truth and Servants of the Lord may have free passage among you." Mary Dyer held the Quaker belief that the inner light of godly wisdom resided in both men and women; yet, rather than challenging the legitimacy of male leadership, she closed her protest with the words, "In Love and in the Spirit of Meekness."

Another English Quaker woman, Mary Fisher, responded differently to Puritan persecution. When the Puritan authorities sent her back to England, she made no effort to return to America. Instead, she embarked on a missionary visit to Turkey, walking partway through 600 miles of its rough country. The Sultan received her as an ambassador, and she was able to preach her Quaker word there as she had been unable to do in the New World.

Discontented women caused considerable trouble in the American colonies, and they were not all of the stature of Hutchinson and Dyer. Protests of women in this period underscored the sexual contradictions of colonial society. In the first half-century of the history of the town of Salem, Massachusetts, five of the nine religious dissenters were females. They included women like Mary Oliver, an Anabaptist, petty thief and runaway wife. Her retort to her male superiors was recited in far less elegant tones than those of Anne Hutchinson. Of the Salem judge, Mary Oliver said, "I hope to live and tear his flesh to pieces."

One of the few women ever to found a town was Elizabeth Haddon. For many years after her arrival in this country in about 1700, she lived alone among the Indians and offered a haven to traveling Friends -- that's friends with a capital F, the term Quakers used in reference to themselves. Her settlement eventually became Haddonfield, New Jersey.

In Salem, Massachusetts, in the late 17th century, 11 young women held the entire town in its power for several frantic months. They received a degree of attention that children and women were seldom accorded. First to point accusing fingers in the Salem trials, their testimony sent members of their own sex to the gallows, including Ann Hibbens of Boston, Anne Cole of Hartford, and Elizabeth Knight of Groton, Massachusetts.

THE MIDDLE 1700s

Moving into the middle 1700s, we meet Barbara Heck and Ann Lee.

Barbara Heck is credited with starting the first Methodist group in America. Before coming to America, Barbara and her husband a lay-minister cousin, Philip Embury, had heard John Wesley preach in Ireland. In New York, they met some other immigrant Methodists, but no services were held and at that time their interest in religion was little in evidence. Except that one day Barbara came into the room where they were all playing cards and suddenly swooped up the cards, threw them in the fire, and is reported to have said, "Brother Embury, you must preach to us or we shall all go to hell, and God will require our blood at your hands." She recruited their fellow Methodists and a few other friends to meet in her house, with Embury preaching. And that was the beginning of Methodism in America.

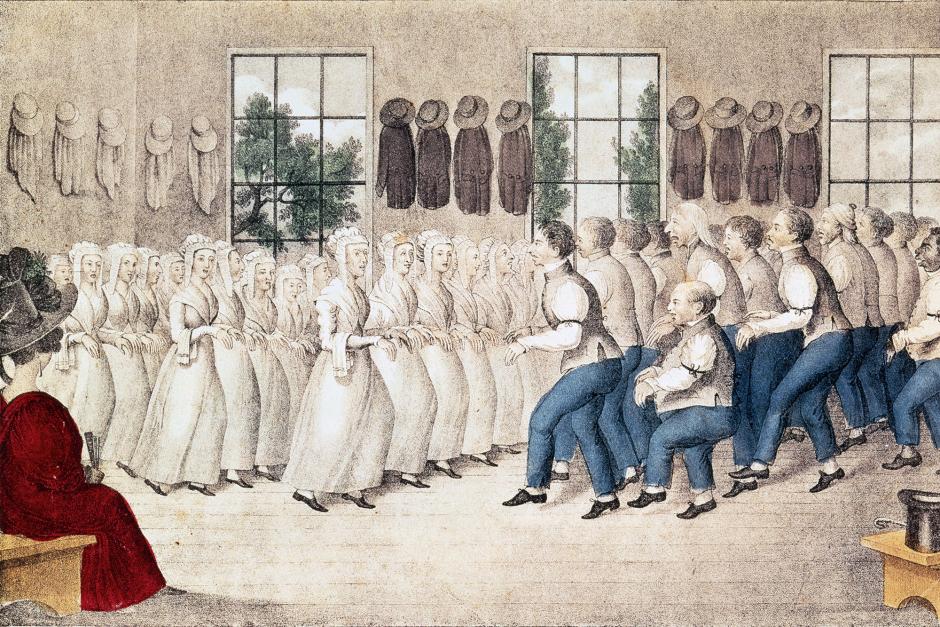

Ann Lee founded the Shaker tradition in the early days of the new American nation. Back in England, she had married a blacksmith, but the marriage was unhappy and her four children all died in infancy. She was at that time a Shaking Quaker. Convinced that she was responsible for the deaths of her children, she went without food and sleep. In her weakened condition, she had a religious vision which convinced her that celibacy was the route to salvation. She was jailed for her beliefs, and while in jail, she had a second vision which revealed to her that the Shakers would fare better in the New World. So she resettled in New York, along with 7 of her followers. She proselytized throughout New England and her charismatic personality won her many converts. In addition to their belief in celibacy, the Shakers also opposed slavery and advocated equal rights and responsibilities for both sexes. The group believed they could perpetuate their numbers despite their ban on "cohabitation of the sexes" by winning converts and adopting orphans. But by the early 1970s, the sect had dwindled to 20 aged members.

A prominent figure in early Mormonism was Emma Hale Smith, "first wife of prophet Joseph Smith." Still today, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints accords her immense prestige. Her accomplishments included the editing of a hymnbook, work among the sick as a nurse and herb doctor, and in 1842, the presidency of the Female Relief Society, the leading women's organization of the Mormon Church.

Sisters Katherine and Margaretta Fox lived in the middle to late 1800s. They seem to have been responsible for the popularization of spiritualism in the United States in about 1848. The Fox sisters were daughters of a nominal Methodist couple with little education.

In 1863, the Seventh Day Adventist Church was founded by Ellen Gould Harmon White and her husband James. When Ellen and her twin sister were about 13, their Methodist parents began to attend Adventist meetings led by a Baptist layman. Ellen married James White at the age of 19; they had four sons. The health of her family got her interested in foods, and her first speaking was on health through food and temperance. Then she and her husband started a small publishing business to give their ideas wider circulation. She began to preach when she was in her forties because she wanted to testify to the miraculous in her own life. When she died in 1915, the Seventh Day Adventists claimed 140,000 members, 2500 clergy, 80 medical centers, and missions on every continent. Their 40 publishing houses had printed 70 books; 25 more were published soon after her death.

Mary Baker Eddy founded the Christian Science religion, in 1879. According to the official church history, she had a fall on the ice in the village of Lynn, Massachusetts. She went to bed and turned to the Scriptures for healing. On the third day, she rose with the pain gone, and began spreading the doctrine that pain could be healed through mental processes. Observers described her as a driven woman who could electrify a classroom or a convocation with her faith. So dynamic was her evangelism--in books, lectures, and informal personal appearances--that by the end of the 19th century, she had more than 22,000 members in 420 churches and an estate of more than two million dollars.

Still another founder during this period was Myrtle Filmore, a co-founder with her husband of the Unity School of Christianity. They conceived of their work as a school, not a church. Charles and Myrtle Filmore had both studied with Mary Baker Eddy. Through their concept of Silent Unity and their constantly expanding publications program, their organization claimed in 1954 that they were reaching a million homes a month with 8 magazines and hundreds of low-priced publications.

1. Legal and political rights.2. Social and industrial rights.3. Moral and religious discrimination.

It has been said that as the women's movement gained momentum, it was Susan Anthony who was the organizer, Lucy Stone who was the eloquent voice, Elizabeth Stanton who supplied the philosophical background and Lucretia Mott who always remained the moral force of the movement.

Susan B. Anthony was known in some circles as "Napoleon in Petticoats." She was born into a family of Quakers, the one religion which did not discriminate against women. In 1848 she began to attend the Unitarian church when strong opposition to the antislavery position developed in the Friends' meeting; even so, she retained her Quaker affiliation. Her efforts towards the abolition of slavery and her work with temperance societies was overshadowed by her influence in the women's rights movement which was her main challenge.

In 1833, the Congregational-oriented Oberlin College had opened its doors to all without regard to race, color, or sex. This was the first real breakthrough in women's education. Among the first registrants were Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown. Lucy's ambition was to "prepare herself as a public speaker on behalf of the oppressed." By the time she graduated in 1841, she was already in the middle of the women's rights movement, giving lecture series on abolition of Saturdays and Sundays and on women's rights the other days.

Lucy Stone and her companion at Oberlin, Antoinette Brown, married brothers. Antoinette was the first American woman to be ordained a minister. She married and had 6 daughters, wrote 10 books, served the Unitarian Church for 15 years, and continued to preach until she was 90. Although she had completed her program in 1850, she wasn't allowed to graduate, but in 1908, Oberlin conferred upon her an honorary doctorate degree. While in her 70s, she traveled to the Holy Land to get water from the Jordan to baptize her grandchildren. Later, she went on a missionary trip to Alaska. She died in 1921 at the age of 96. A contemporary account estimated that at the time of her death in 1921, there were 3000 female ministers in the United States.

Lucy Stone's husband was Henry Blackwell, an ardent advocate of women's rights. His sister, Elizabeth Blackwell, devoted her energies to hammering down the doors that kept women from entering the field of medicine. She was finally accepted as a medical student at Syracuse. It was the 29th medical school to which she had applied for training.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the eloquent suffragist, was Presbyterian. At the first women's rights convention which she helped to organize at Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, she wrote a Declaration of Sentiments calling for the reform of discriminatory practices that perpetuated sexual inequality.

Dorothea Dix, noted for prison and hospital reform, got her start when asked to teach a Sunday School class in a Massachusetts jail in 1841. She worked in several countries in Europe as well as here in America, giving particular attention to humanizing the care of the insane. Her investigations and reports brought many needed legislative reforms.

--emancipation of the mind from narrow religious beliefs--abolition of slavery--freedom for women

Frances Willard founded the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Over a period of 20 years, she built the WCTU into an army of 200,000 members dedicated not only to prohibition but also to wider social concerns, including woman's suffrage. There were departments in the WCTU for every phase of life that touched the American home, from kindergartens to prisons, from physical culture to prostituion. Many of the churches which before had been unable to embrace the cause of women't rights with any enthusiasm could nevertheless give unqualified support to the WCTU, as a crusade against drunkenness. Frances Willard had wanted to become an ordained Methodist minister but said that she felt driven from the altars of the church and instead turned to social reform. She did work for a time with evangelist Dwight L. Moody. She also was instrumental in organizing the Prohibition Party and authored several books, including Woman in the Pulpit.

Carry Nation shared some of the same motivation as did Frances Willard in fighting the evils of liquor, but Carry put her faith into direct action and consequently elicited far less male admiration. The saloonkeepers both disapproved of her and dreaded her methods such as coming in and smashing their stock. She was actually arrested over 30 times for wrecking saloons. She often posed for pictures with a Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other, saying that both were divinely inspired. Then she sold souvenir hatchets to get funds to establish a home for the wives of drunkards.

The Grimke family in Charleston, South Carolina, were slave-owning Presbyterians who became Quakers. Daughters, Sarah and Angelina Grimke, were among the first women to speak out against slavery and for women's rights. They also were among the earliest Americans to dispute St. Paul's teachings on the inequality of women. The Grimke sisters became the first women to speak to mixed audiences of men and women, and the strong objections to these appearances was what catapaulted them into women's rights. In 1838, Sarah wrote, "The idea is inconceivable to me that Christian women can be engaged in doing God's work and yet cannot ask His blessing on their efforts except through the lips of a man."

Perhaps the most famous abolitionist was Harriet Beecher Stowe, the epic author of the antislavery cause. She was the daughter of one preacher and the sister of seven more, and the wife of a professor of Biblical Literature. She was the mother of five children. She found a focus for her own Christian idealism in the antislavery cause. Her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin, sharpened the moral issues that led to civil war. In 1862, she was in Washington urging Abraham Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. The legend is that Lincoln shook her hand and said, "So this is the little lady who made this big war."

Harriett Tubman was an escaped slave connected to the success of the Underground Railroad through which she brought 300 men, women and children. There was a price of $40,000 on her head, but she said that when you were a Negro and a woman, surely you had nothing to lose. Harriett took a leading part in the growth of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in upstate New York. She was a deeply religious person who never doubted that her actions were guided, according to her own statement, by "divine commands conveyed through omens, dreams, and warnings."

Margaret Fuller was a leading spirit in the transcendentalist group and was co-editor with Ralph Waldo Emerson of "The Dial."

Mrs. Sarah Hale was editor of "Godey's Lady's Book;" she used its pages to campaign for one cause after another.

Margaret Sangster, of the Dutch Reformed Presbyterian church in Brooklyn Heights, was a magazine editor and author. After her husband's death in 1870, she turned seriously to writing. She spent the rest of her life as a Christian leader of women. Believing that she had a "mission to girlhood," she answered questions with letters and short essays addressed to American girls in popular magazines of the 19th century. Until shortly before her death, she opposed the cause of woman's suffrage, believing it to be a threat to the welfare of the family. Her views changed, partly because of the courage shown by English suffragists and partly because she had come to recognize, according to her own words: "...the helplessness of woman as a competitor in the labor market when she has no voice in the making of the laws affecting her."

American Baptist Ann Judson went to Burma. Mabel Cort, a Presbyterian, went to Thailand. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Harmon Spalding were the first white women to cross the Rockies via the Overland Route, in 1836. As missionaries to the American Indians, both were ordained ministers of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which was Congregational and Presbyterian.

Maggie Van Cott was a Methodist evangelist from New York. She conducted her first revival meetings in 1868, after the death of her husband. Despite her lack of theological training, she overcame the opposition of many Methodists, both lay and clerical, who disapproved of a "lady preacher." Some welcomed this handsome woman revivalist as a means of offsetting the lure of actresses and the heretical female lecturers of the era. But her career was not the result of any specific policy along these lines by the Methodist Episcopal Church, and it took a very long time for them to license women for preaching.

Mary Lucinda Bonney and Amelia S. Quinton first worked in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. These two Philadelphia Baptists in 1879 organized the first of a series of mammoth petitions to protest the alienation of tribal lands in Oklahoma and elsewhere, calling for allotment to individual Indians. Then they formed the first national organization for Indian reform, later called the Women's National Indian Association; eventually it set up 50 missions to Christianize and civilize the Indians.

Anna Snowden was the first female theologican in America. Theoretically, Boston University had always welcomed women to both its student body and its faculty. The first woman to enroll in the School of Theology did so with little fanfare under the name of Anna Oliver, not her real name, to save her family embarrassment, especially her brother, an Episcopalian rector. She had first enrolled in Oberlin, but found that, in spite of its faculty policy of welcoming all educationally qualified students, there was still much discrimination against women in their theological department. So she transferred to Boston and graduated in 1876. Problems relating to her ordination kept the Methodist General Conference busy for quite some time. At a church in Passaic, New Jersey, she brought in Amanda Smith as an assistant. Amanda was an outstanding Negro evangelist, born a slave, who in adulthood traveled as a missionary and evangelist to India and also to Scotland, Italy, England, Egypt, and various African countries.

Evangeline Booth was the daughter of the founders of the Salvation Army. It was founded in England in 1865 by General William Booth and his wife Catherine, and was introduced into America 15 years later. The sons and daughters of this prolific family and the people they married, entered vigorously into the Army's evangelistic pattern, and the movement spread rapidly around the world. Evangeline was a commander, both in the U.S. and in the International Salvation Army. It's interesting to learn that she was named after Little Eva of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

A most colorful evangelist was Aimee Semple McPherson, founder of the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel. Born in Canada, she arrived in Los Angeles in 1918 with nothing but $10 and a tambourine. Five years later she was preaching to crowds of 5000 inside her $1,500,000 Angelus Temple, headquarters of the International Church of the Four-Square Gospel, a name which came to her in, according to her own words, "a moment of divine inspiration." She was known as the "Barnum of religion." She helped herself to the contents of the collection plate; she drove about in a "gospel auto," and she made stopovers in Parisian nightclubs on the way to the Holy Land. This dyed blond, thrice-married evangelist usually appeared in a white celestial robe and a blue cape to preach her gospel and practice her "miracle" faith healing. It didn't matter that once she punched her business manager, who also happened to be her mother. Nor did it matter that her flock discovered she'd been off on a tryst when she claimed she'd been kidnapped. Wealthy, frolicking Sister Aimee was able in her 53 years to set up no fewer than 400 churches and 200 missions, a Bible College, and a radio station.

In more recent times, a much more respected but less sensational woman evangelist, from the state of Georgia, was Ruth Carter Stapleton, the sister of President Jimmy Carter.

A Missouri-born evangelist and faith healer, Kathryn Kuhlman, was an ordained minister of the Evangelical Church Alliance. She had her first religious experience when she was 13 and started preaching the next year. After another religious experience in 1946, she began to talk more and more about the Holy Spirit. During one of her sermons, a woman in the congregation claimed to have been cured of a tumor. Following that experience, Kuhlman began to preach about the Holy Spirit's power to cure. In addition to her preaching and healing, she was president of the Kathryn Kuhlman Foundation, a charitable organization devoted to missionary churches, drug rehabilitation, and the education of blind children.

Such respected professors as Dr. Mary Lyman of Union Seminary in New York City and Dr. Georgia Harkness of Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, California, did much to raise the popular respect for women theologians.

Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton, born in 1774, was named 200 years later as the first American- born saint in the Roman Catholic religion. She was a fragile socialite with luminous dark eyes, and intensely religious, but an Episcopalian. She became a widow at 29 when her husband, a wealthy New York merchant, died during their trip abroad. Elizabeth stayed in the home of an Italian family who made efforts to convert her to Catholicism, and she wrote home that she "laughed with God" at their efforts. Nevertheless, within a year after her return to the United States, Elizabeth converted to the Catholic faith. She moved with her 5 children to Maryland where she became a nun. As Mother Seton, she founded the American branch of the Sisters of Charity as well as a free paraochial school, the first in the United States. Mother Seton's many good works, her reputation for saintliness, and the miracles later attributed to her finally led, in 1975, to her canonization as America's first native-born saint.

Frances Xavier Cabrini, born in 1850 in Italy, was the first American citizen to achieve sainthood. She came to America at the age of 38. During her lifetime, she established 65 orphanages in Italy, the United States, Central America, and South America. She also established numerous hospitals in the United States.

Katharine Drexel, born Catherine Mary Drexel in 1858, was a Philadelphia heiress who devoted her life and her multimillion-dollar fortune to educating and seeking justice for Indians and African-Americans. Over the course of 60 years—up to her death in 1955 at age 96—Mother Katharine spent about $20 million in support of her work, building schools and churches and paying the salaries of teachers in rural schools for blacks and Indians. On October 1, 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized Blessed Katharine in St. Peter’s Square, making her only the second American-born saint.

Dorothy Day, born in 1897, converted to Catholicism at the age of 30; she had been a socialist reformer. She co-founded a monthly newspaper, the "Catholic Worker," dedicated to social reconstruction. During World War II, it was an organ for pacifism and the support of Catholic conscientious objectors. The newspaper has taken radical positions on a good many issues.

Sonia Quitsland, a professor of religion at George Washington University, also headed an organization called "Christian Feminists" during the 1970s. The purpose of this organization was to expand the role and status of women in the Catholic church.

We have observed that many women in religion demonstrated a remarkable capacity for being and doing more than one thing at a time. Often they were writers and ministers, administrators and teachers, theologians and mothers. Many of these women achieved remarkable things within the boundaries of their orders and denominations. Others were dispossessed by the structure and were forced to forge new forms, meeting whatever came, both realistically and creatively. This is part of the heritage of today's women. We owe a great debt to the women of faith who have gone before us.

Bibliography: American Church Records

Compiled by Beverly Whitaker, MA

- Gaustad, Edwin S. Historical Atlas of Religions in America. New York: Harper and Row, 1976. Its 72 maps and 62 charts and graphs make it an indispensable reference source for a study of any religious group in America.

- Jacquet, Constant H. ed. Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, annual. It lists all major current denominations in the United States and Canada with the names and addresses of current officers. It provides a capsule history of each denomination, its distinctive doctrinal position, main depositories of church historical material, and church-related colleges and universities in the United States and Canada.

- Mead, Frank S. Revised by Samuel S. Hill. Handbook of Denominations in the United States, 10th edition. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995. Most libraries will have a copy of this or an earlier edition on their reference shelves. This book is widely recognized as an objective and reliable source of information about religious bodies in the United States, with more than 200 groups discussed. It outlines historical background, doctrines, and governmental organization. This volume contains an up-to-date list of addresses for denominational headquarters, bibliographies, and a glossary of terms.

- Noll, Mark A. A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1992. The author provides an excellent historical overview of the evolution of Christianity in the United States and Canada from the early seventeenth century to the present. It includes five statistical tables which graphically show the denominational shares of religious adherents for various periods.

- Whitaker, Beverly D. "Churches in Early America" Reference Cards. Kansas City, MO: Genealogy Tutor, 1998. Individual reference cards are presented for 16 of the denominations which dominated American religious life in the colonial period and on through the18th century. Themes: Chronology, Records and Resources, Bibliography.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Testimonies_of_Ann_Lee-79847f6d9d8f4c2fab8a3a539c320942.gif)