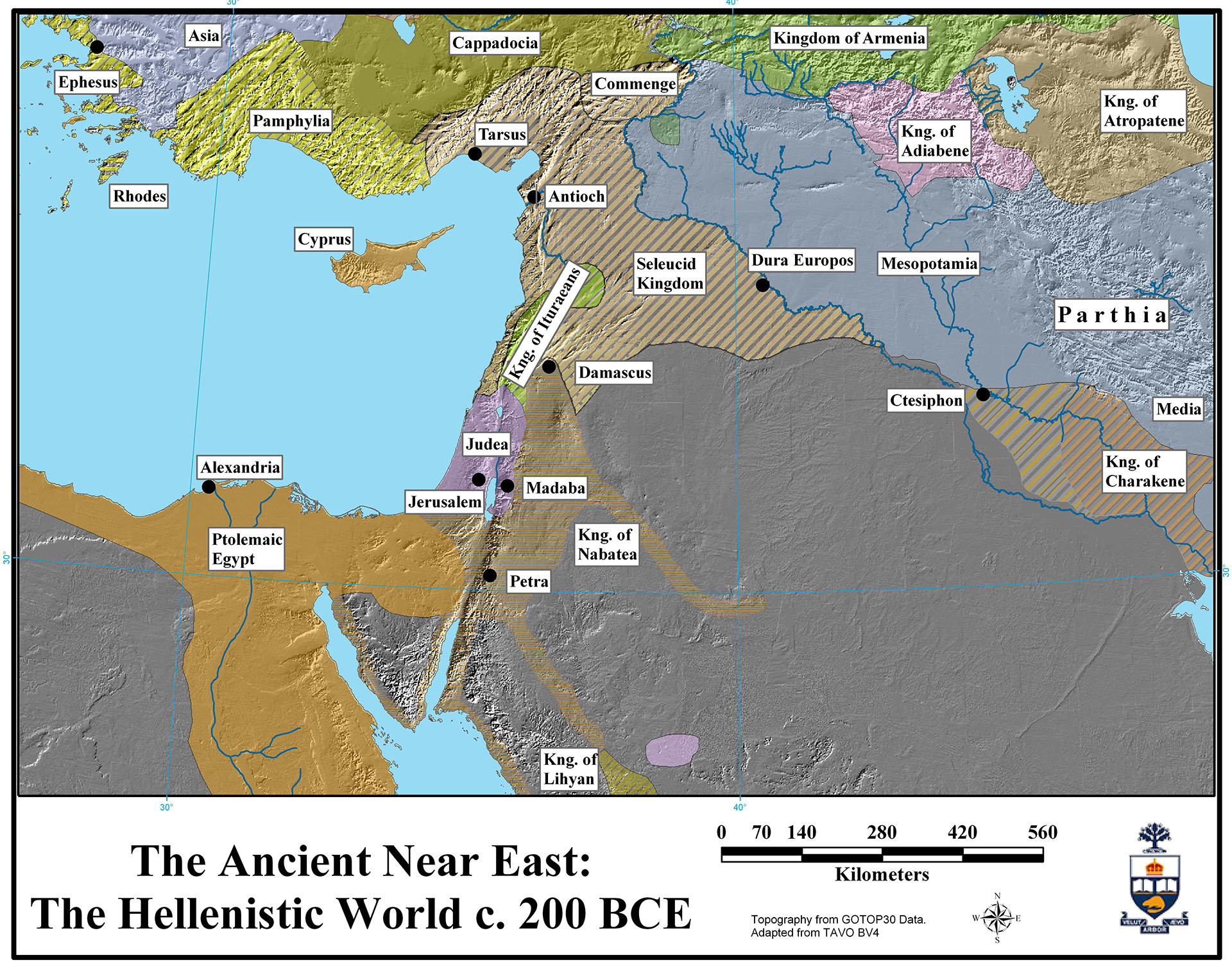

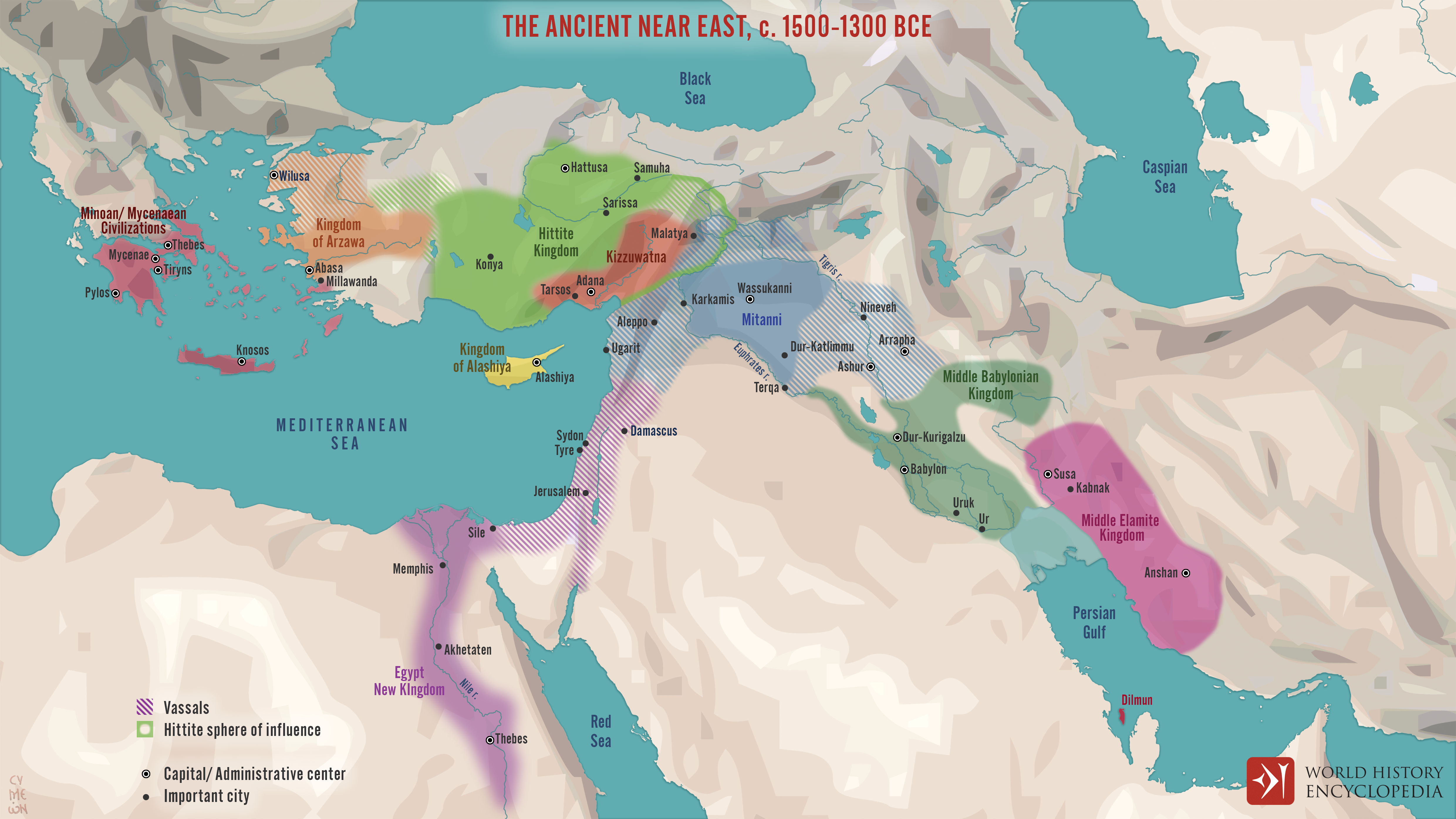

Any serious attempt to understand how ancient Israel conceived of God must begin before Israel, in the long and layered religious world of the Ancient Near East (ANE). Between roughly 2000 and 200 BCE, the lands stretching from the Nile to the Zagros Mountains formed one of the most interconnected cultural environments in human history. Religious ideas and depictions moved easily across the empires and centuries of Mesopotamia: myths travelled with caravans; rituals migrated alongside merchants; linguistic speech and thought patterns persisted through human interaction; and religious images of the divine circulated with soldiers, scribes, traders, artisans, and people in general.

Israelite religion did not stand outside this world. It emerged from within it, shaped by the same cultural forces as other communities were; sharing symbolic vocabulary; and inheriting mythological structures that animated the civilizations around them. To read the Hebrew Bible without reference to this broader environment is to attempt to interpret a conversation after entering the room halfway through. That is, the Hebrew Bible is a deeply interwoven part of the syncretism of worship and religion in the Ancient Near East (ANE).

What Israel received from this world was not a set of isolated (Jewish-oriented) motifs but an entire religious grammar and divine pantheon from its neighbors. This included ways of imagining the divine, in structuring sacred reality, and in narrating the earth's cosmic origins. The Israelites did not invent the idea of a divine pantheon, a cosmic mountain, a primordial sea, or even the categories of creation, covenant, kingship, temple, and priesthood. These concepts all belonged to a long-standing cultural inheritance shared between the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Canaanites, Hittites, Elamites, and others. Israel’s later innovations - it's ethical monotheism, covenantal theology, and eventual rejection of polytheistic+henotheistic syncretism - only make sense against this deep backdrop of inherited religious possibilities.

Thus the emergence of a single, universal God in Israel is not a sudden metaphysical rupture but a creative reconfiguration of older materials which streams of confluence met the religious shorelines of Israel's move towards incipient monotheism. What appears in Scripture as claimed revelation is rather the outcome of centuries of interaction, adaptation, reinterpretation, conflict, and theological transformation towards a mature monotheistic system. Israel’s movement from a small hill-country people to a monotheistic community cannot be understood apart from this evolutionary process.

It is precisely the function of this Supplementary Essay to reconstruct Israel's evolving worship and beliefs. These were the years in which the rich looms of Jewish theology grew from the syncrenistic soils of ANE polytheism and henotheism. And from these years of evolving maturity we later have in the Hebrew Bible the final fruits of that period playing out on the world stage between the Romans and Jews whose gods struggle one against the other: (Zeus) Jupiter vs. (El) Yahweh.

It was from this interplay that Israel's evolving monotheism merged and gave birth to later Judaic thought and Christianity. Early Israel was more a participant in a centuries-deep tradition of evolving religion than it was a theological innovator. The idea of a single, universal God arises not at the beginning of its early history but at the end of this long process of interaction, conflict, reinterpretation, and creative adaptation.

Thus, this first sub-essay explains the environment in which Israel’s earliest understanding of the divine took shape. It is the soil from which all later biblical thought grows.

II. The Religious World of the Ancient Near East as Context for Israel's Evolving Religion (2000-1200 BCE)

Long before Israel emerges as a distinct people, the Ancient Near East had already developed an extraordinarily stable-and-interconnected religious worldview. Despite the differences between regions-Sumer and Akkad in the south, Assyria in the north, Ugarit and Canaan in the west, Egypt along the Nile - their mythological imaginations displayed remarkable coherence. Names differed, but the functions, relationships, and dramatic patterns of the gods were deeply familiar across the entire region.

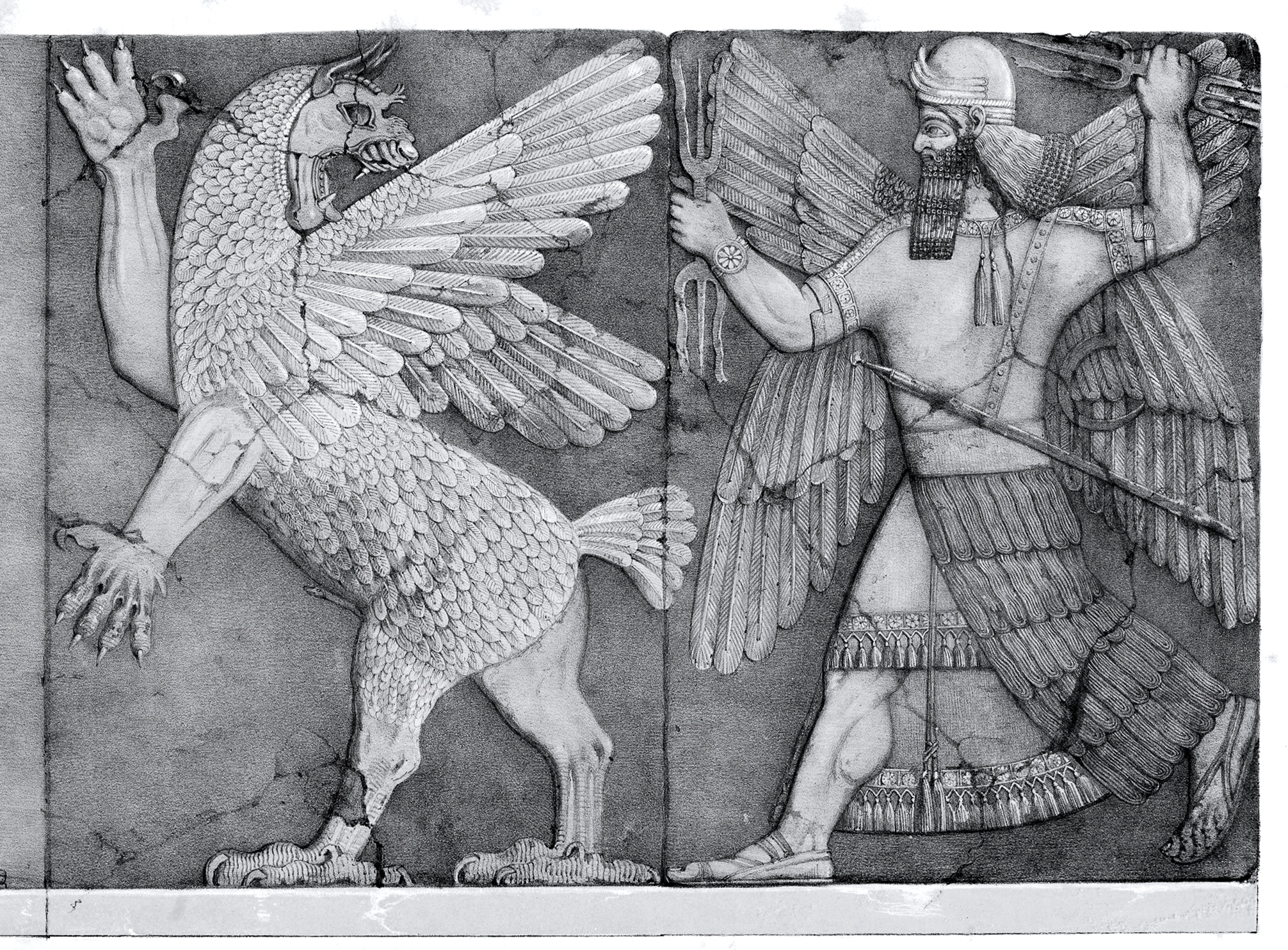

The divine world was understood as a richly populated and hierarchically structured reality. High gods presided over the cosmos and delegated authority to younger deities. Storm gods wielded lightning and brought both destruction and fertility to the land. Mother goddesses nurtured creation and presided over the cycles of birth and rebirth. Sea monsters and chaos dragons threatened cosmic order, requiring the intervention of heroic gods. Fertility gods animated the agricultural seasons. Warrior deities defended cosmic stability. Spirits guarded the dead. Divine messengers traveled between realms, delivering decrees from the high gods to the human world.

These patterns were not accidental. They formed a shared mythic grammar across the ANE, as recognizable in Ugarit as in Babylon, as familiar in Hatti as in Jerusalem. And within this grammar, several motifs were nearly universal, structuring how ancient peoples imagined divine action.

- The first motif was Creation out of Chaos. Mesopotamian myths describe the primordial conflict between Tiamat, the saltwater sea, and Apsu, the freshwater deep. In Ugaritic tradition, the storm-god Baal battles the chaotic sea Yamm and the death god Mot to establish order. These stories are not identical, but they express a common intuition: the cosmos emerges through the subduing, calming, or structuring of primordial waters. Genesis 1 participates in this tradition, even as it transforms it -God does not battle the sea but commands it; the tehom, echoing Tiamat’s name, is no longer a goddess but an impersonal deep waiting to be shaped by divine word.

- A second motif was The Flood. The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Atrahasis Epic preserve ancient stories of humanity nearly extinguished by divine judgment, rescued only through a chosen survivor warned by a benevolent deity. When the Noah narrative appears in Genesis, it stands not as an isolated revelation but as a profound ethical reinterpretation of a story known across the region.

- A third motif was the Divine Council. In Mesopotamia, the gods assemble to deliberate over cosmic matters. In Ugarit, the council of the ’ilanu meets under El’s authority. Similarly, the biblical passages such as Psalm 82, Job 1-2, and 1 Kings 22, presuppose this same iconography: Yahweh presides in a heavenly court, addressing and directing divine beings.

- A fourth motif was Sacred Topography. Throughout the ANE, the divine realm was conceived as elevated and ordered. Ziggurats symbolically represented mountains that connected heaven and earth. Ugarit’s Mount Zaphon served as Baal’s cosmic throne. Israel later reimagines this tradition through Mt. Sinai and Zion.

- A fifth motif was the Divine Family of Gods. The high god typically had a consort; together they generated the pantheon. Thus El and Asherah in Canaan, An and Ki in Sumer, and Amun and Mut in Egypt. Israel’s own early religious practices - attested archaeologically through inscriptions referencing Yahweh and Asherah - suggest a similar pattern before monotheistic reform.

These immersive motifs were not unfamiliar to Israel; they formed its cultural and religious inheritance. Israel’s earliest theological imagination simply spoke the language of its world.

If Mesopotamia provided the deep mythic backbone of Israel’s world, Canaan supplied its immediate religious environment. Israel’s ancestors lived in the same land, spoke the same language family, and shared cultural practices with Canaanite communities. For centuries, the boundary between “Israelite” and “Canaanite” was fluid, permeable, and often invisible.

The Canaanite Divine Family

- El - creator, patriarch, king

- Asherah - mother goddess

- Baal-Hadad - storm god, warrior, fertility giver

- Anat - warrior goddess

- Astarte (Ishtar) - love and war

- Yamm - sea chaos

- Mot - death

Many of these figures appear in the Hebrew Bible, sometimes directly, sometimes in refracted form. The title “El Elyon” (“God Most High”) in Genesis and Deuteronomy unmistakably echoes the high god El. The theophanic image of Yahweh enthroned above the waters in Psalm 29 resonates with Baal’s storm-god imagery. The monstrous figures of Leviathan, Rahab, and the Tanninim recall Ugaritic sea monsters defeated by Baal. The prevalence Yahweh's consort, Asherah, as depicted by numerous Asherah poles witnessed across Israelite cultic sites, later condemned by Israel's prophets and reformers alike, testifies to the goddess’s persistence in popular devotion.

The archaeological record reinforces this picture: household shrines, amulets, and cultic objects from Iron Age Israel closely resemble Canaanite materials. Importantly, Israel did not emerge as a religious alternative to Canaan but as one variation within the broader West Semitic religious tradition. Only later, under prophetic critique and exilic trauma, would Israel strive to distinguish itself sharply from its neighbors.

This is what is meant by the evolution of syncretistic religion. That early Israel had strong continuities with its Canaanite neighbors until later, when it diversified its identity from its neighbors, so that it's later religious evolution beheld it as a strictly monotheistic religion.

- Creation - Marduk fashions the world by slaying Tiamat and splitting her body into heaven and earth; Genesis removes the violence, reconfiguring creation as an act of peaceful, embodying speech.

- The Flood - The flood narratives of Gilgamesh and Atrahasis become ethically charged in Genesis, where divine judgment responds to moral corruption rather than divine inconvenience to humanity's "noise" along with it's overpopulation designed to serve the needs of the gods.

- Chaos Myths - The combat myths of Marduk and Baal echo faintly in biblical poetry whenever Yahweh subdues the waters or defeats Leviathan.

- Cultic Worship Sites - The idea of a temple as a microcosm of the universe parallels Mesopotamian ritual architecture, where sacred space symbolized cosmic structure.

- Language also reveals these inheritances. Hebrew’s tehom (“the deep”) preserves the memory of Tiamat; Eden resonates with the Akkadian edin, meaning “plain” or “steppe”; divine epithets like Shaddai have possible Amorite or Akkadian roots. Linguistic memory carries mythic memory.

IID. Mechanisms of Religious Exchange in the ANE

IIE. Summary Table - ANE Themes Israel Inherits

| ANE Theme | Mesopotamian/Canaanite Expression | Biblical Reframing |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | Combat with chaos monsters (Tiamat, Yamm) | Order through divine speech (Gen 1) |

| Flood | Utnapishtim, Atrahasis | Noah story (ethical focus) |

| Divine Council | Council of the gods | Yahweh presides over “gods” (Ps 82) |

| High God | El, Ilu | Yahweh merged with El |

| Consort | Asherah | Asherah suppressed but visible in archaeology |

| Storm God | Baal-Hadad | Yahweh adopts storm theophany |

| Sacred Mountain | Zaphon, ziggurats | Sinai, Zion |

| Grammar of Myth | Shared Semitic lexicon | Hebrew narrative reformulation |

- Part I - Foundations: The Birth of the Sacred

- Prequel - Before History: Humanity in the Long Dawn of Becoming

- Essay 1 - Animism and the Living Cosmos

- Essay 2 - From Tribe to Totem

- Part II - The Age of Gods

- Essay 3 - The Mesopotamian Fertile Crescent

- Essay 4 - Egypt, Indus, and Minoa Sacred Cultures

- Essay 5 - From Polytheism to Henotheism

- Part III - Axial Awakenings

- Essay 6 - Ancient Israel, Persia, and Monotheism

- Essay 7 - India's Axial Age

- Essay 8 - Greece and the Birth of Reason

- Part IV - The Sacred Made Universal

- Essay 9 - The Age of Universal Religions

- Essay 10 - Modernity and the Eclipse of the Sacred

- Essay 11 - The Rebirth of the Sacred

- Part V - Conclusion of Series

- Essay 12 - A Processual Summation of Worship and Religion

- Essay 13 - The Way of Cruciformity: When God Refused Power

- Essay 14 - Messiah: From Anointed Saviour to Suffering Sacred

- Essay 15 - Becoming Aligned with the Sacred

- Part VI - Supplementary Materials

- SM 1 - The Ancient History of Mesopotamia

- SM 2 - The History of Language in Ancient Mesopotamia

- SM2a - How the Ancient Sumerians Created the World’s First Writing System

- SM 3 - The Ancient History of the Hebrew Language

- SM 4 - How the Ancient Near East Gave Shape to Israel's God:

- Why the ANE is Essential for Israel's Received Theology (I-II)

- Affecting Cultic Syncretism Across the Ancient Near East (III-V)

- Cultural Identity Formation & the Rejection of Syncretism (VI-IX)

- SM 5 - The History & Compilation of the Hebrew Bible:

- From Oral Memory to Proto-Canon (I-II)

- Exile, Redaction, and the Birth of Scripture (III)

- Second Temple Scribalization to Canonization (IV-V)

- SM 6 - The Unhelpful Oxymorons of "Biblical Authority" & "Inerrancy"

- SM 7 - The Evolution of Inerrancy: From Ancient Plurality to Modern Certainty

- SM 8 - A Historical-Theological Study of "Son of Man" vs "Son of God"

- SM 9 - The Song of Gilgamesh & Other Ancient Flood Stories

- SM 10 - Isaiah as a Living Textual Tradition: Manuscripts, Variants &Transmission

- SM 11 - From Scroll to Scripture: Bible Versions, Variants & their Histories

- SM 12 - The Gnostic Mysterion: the Crisis of Sacred Becoming

No comments:

Post a Comment