SEP 20, 2022

New Laws: Thermodynamics and Evolution

By the mid-19th century, with modernity in full swing, two new scientific fields would enter the fray that, at first, seemed only to confirm its increasingly disenchanted worldview: the study of thermodynamics and the theory of evolution.

One seemed to imply that all available energy in the universe was irreversibly running out, leading to the eventual freezing death of the cosmos; the other, that life had developed completely naturally through blind processes of chance mutation and selection.

Such ideas seemed to fit well with the rest of the metaphysics and cosmic story of modernity: namely, a blind, indifferent universe without goal or meaning. Or, perhaps a better way to see it: these paradigms were simply interpreted according to the dominant worldview of the time—one reductionistic, pessimistic, and bleak—and thus only seemed, at first blush, to confirm people’s popular perceptions.

Nevertheless, these new paradigms would eventually become key to a total re-evaluation of reductionism itself—even if, in the late 1800s, no one could yet foresee this.

Let’s start with thermodynamics.

As we’ve seen, classical physics had come to be defined by its assumption that everything can be reduced to particles in motion, which Newton had shown to obey certain mathematical laws that let us predict future states and reconstruct prior ones with just a few measurements—the way you can deduce where a cue ball will end up (as well as where it was coming from) as long as you know its current position and velocity. Reductionistic theory assured that the world was a deterministic machine, and the only thing stopping us from predicting the behavior of everything from clouds to kings with absolute certainty (the way we can predict eclipses or the return of comets, for instance) was simply the practical difficulty of getting all the measurements.

Well, the formulation of the famous laws of thermodynamics would pose a major challenge to that assumption, and begin to problematize the very premises of reductionism.

The laws of thermodynamics came about by studying how energy behaves in closed or “isolated” systems—which is to say, containers cut off from the rest of the environment. Originally, scientists were looking at how heat acted inside engines (steam engines being quite the craze in the early 1800s). Today we might think of a thermos as a good example of an isolated system, since it’s specifically designed to retain the temperature of what’s inside by keeping it as insulated as possible from the surrounding environment. By studying how heat behaved in closed systems like this, scientists sought to formulate universal laws about energy (just as Galileo formulated universal laws of motion by means of isolation and simplification).

As codified in the first law of thermodynamics, then, it was discovered that, in a genuinely closed system, the total amount of energy remains fixed and unchanging. No energy is coming in or going out, nor can energy itself ever be created or destroyed. Its total amount will remain constant—even if it changes form or distribution.

So far, so good. (This idea of “conservation” pairs well with the idea of the conservation of motion in Newtonian physics. Nature always balances her books in the physical accounting of the world.)

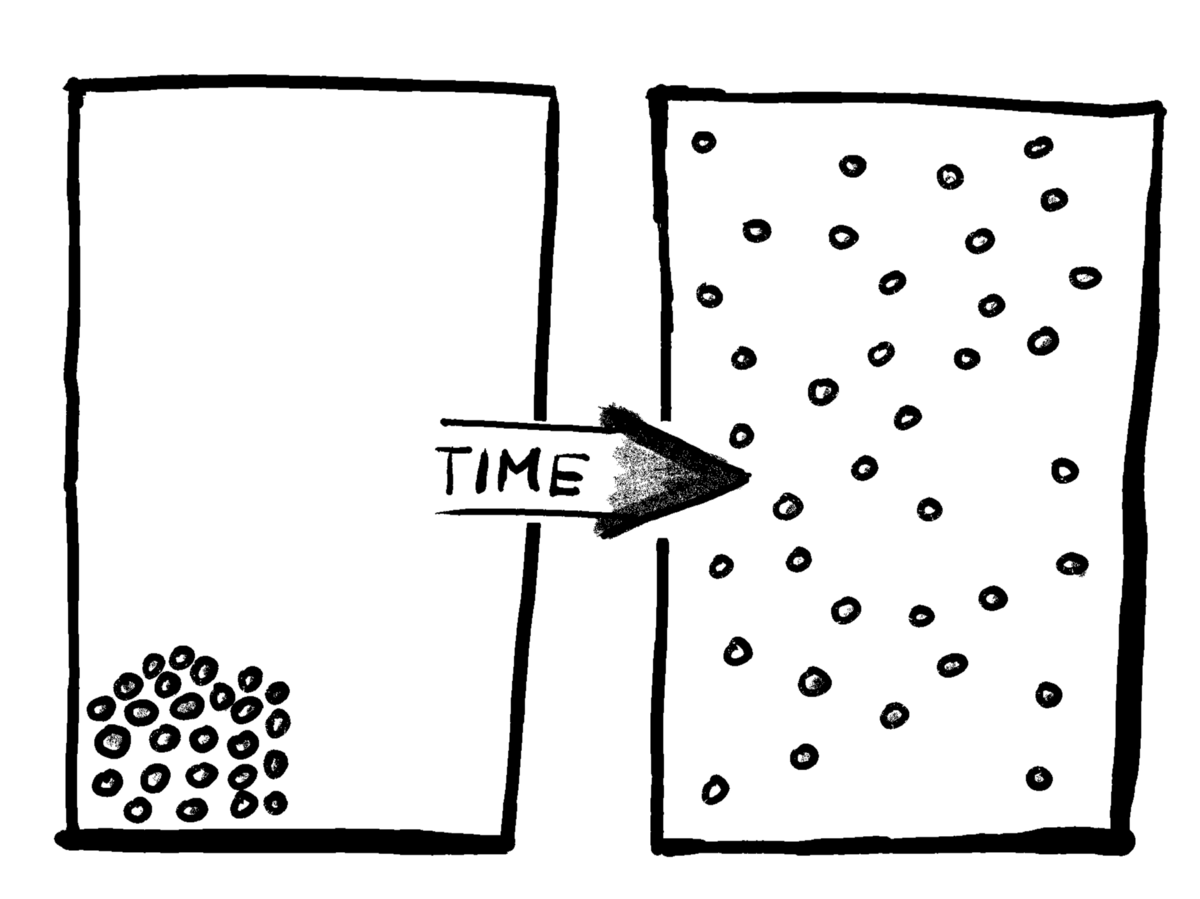

But things become more problematic with the second law, likewise deduced from observation, which says that the total energy in the system will gradually and irrevocably dissipate until a homogenous equilibrium state is reached. Differences even out, distinctions blur, and gradients are eradicated over time.

Think what happens when you add hot water to a thermos of cold water. That energetic hot water won’t stay all clumped together in one place; instead, the heat will spread out (or “dissipate”) until all the water in the thermos finally becomes one uniform temperature. This is called “entropy,” and the second law asserts that free energy is always being entropically dissipated over time—degraded, you could say, until eventually it’s totally useless and the system reaches a uniform, featureless balance:

equilibrium.

This insight created a big problem for the conception of Newtonian reality as particles in motion whose future and past states could all be predicted with deterministic certitude. Instead of being able to deduce it, once something reaches equilibrium it’s impossible to know its earlier state (AKA its “initial conditions”). You can’t deduce from a warm thermos that there was ever hot water of a certain temperature added to cold water of a certain temperature; all of that information is lost once the temperatures mix due to entropy.

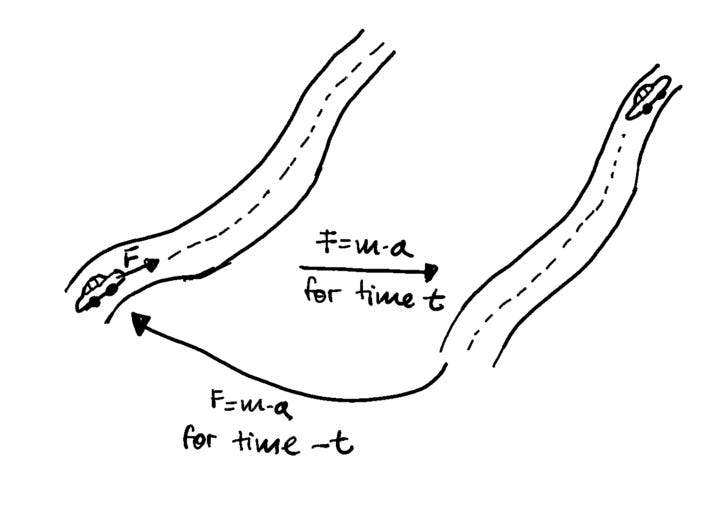

The laws of Newtonian physics were completely reversible. Gravity might bring a rock down, but enough force against gravity could throw a rock right back up again. The laws of thermodynamics, by contrast, had a clear irreversible trajectory. The hot and cold water will mix spontaneously over time, but trying to separate them again requires a lot of energy—free energy that no longer exists in the system, precisely because it’s been dissipated.

In short, according to Newton’s laws, time was negligible; according to the laws of thermodynamics, however, time has a clear direction. It gives us what Arthur Eddington famously called the “arrow of time.” And, according to the laws of thermodynamics, that arrow seemed to move only one way: from a gradient to equilibrium, from difference to sameness, from distinct order to jumbled chaos. According to the second law, entropy in a closed system can only increase, suggesting the universe itself must be like an engine irrevocably running out of fuel, destined for dissolution and death.

At least, that was how its cosmic implications came to be interpreted by an increasingly modernized world. Primed to imagine life as a meaningless accident in an indifferent cosmos, this discovery fell comfortably in line with the grim reductionist worldview—even though it actually flew in the face of the scientific reductionism that had helped found that worldview (and would eventually help overthrow it entirely—something we’ll come back to).

Anyway, the cracks in the reductionistic edifice didn’t end there.

Interestingly, at roughly the same time the laws of thermodynamics were being discovered, the theory of evolution erupted onto the scene and caused its own disruptive stir. According to this new theory, the vastly different kinds of species we see in the world came about not through divine fiat all at once (as the traditional religious story had told it), but through an eons-long unguided process of continual branching and pruning of the tree of life from the shoot of an initial common ancestor.

As Darwin expressed it concisely in The Origin of Species in 1859:

As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.

In this way, life was continually diversifying over time, creating more and more novelty, generating more and more difference. “And as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being,” concluded Darwin, “all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection.”

This process seemed to follow its own set of universal principles, different from Newtonian law. The “elaborately constructed forms” of the animals, says Darwin, “have all been produced by laws acting around us”—laws new to science, such that “whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” That is, against the static universe of Newtonian physics, a dynamic process of diversification was leading to more and more elaborate forms over time.

Again, despite the challenge this posed to classical reductionism, the immediate interpretation of this theory only fed the growing divide between materialist reductionists and religious traditionalists. Against the protests of the traditionalist holdouts (who fought evolution as a threat to their mythological sense of meaning), those committed to modernism and science felt compelled to embrace the conclusion that Darwin’s insights confirmed the basic hunch of the reductionist worldview. Life was not the product of any Intelligent Designer, but only blind mutation and nature’s savage “culling of the herd.”

Such a sense of nature—“red in tooth and claw,” as the poet Tennyson assessed it for his religiously shaken fellow Victorians—was the last straw for any religiously inclined rational mind, now helplessly buffeted from an ancient traditional holism of cosmic meaning and benevolent care:

Are God and Nature then at strife,

That Nature lends such evil dreams?

So careful of the type she seems,

So careless of the single life;

That I, considering everywhere

Her secret meaning in her deeds,

And finding that of fifty seeds

She often brings but one to bear,

I falter where I firmly trod,

And falling with my weight of cares

Upon the great world's altar-stairs

That slope thro' darkness up to God,

I stretch lame hands of faith, and grope,

And gather dust and chaff, and call

To what I feel is Lord of all,

And faintly trust the larger hope.

But, like entropic energy itself, that larger hope would only grow fainter and fainter with time, until, by the 20th century, it seemed to dissipate altogether. The reductionistic worldview ushered in by modernity had become the new cultural default. The old naïve holism of religion was lost, along with all its assumed sense of value and meaning. Reductionist science—along with nihilistic interpretations of thermodynamics and evolution—had fundamentally changed people’s perspective regarding the part that humans played in the cosmic whole, leading them to no longer see themselves as agential wholes but only deterministic meat-suits moving through space.

As a consequence, people today who feel they know a thing or two (and likely find themselves in positions of power) can, as we said, confidently assert: Life’s just a cosmic accident; the fit survive by preying on the weak and stupid; morality’s a fairy tale invented to keep people in line; and, sooner or later, the sun will explode, the universe will end in heat death, and none of this dazzling sound and fury will have meant a goddamn thing—so why not live it up while we can? By the early 20th century, all of the ingredients for the meaning crisis were firmly in place.

As it turns out, however, this nihilistic worldview is actually… well… just simply wrong. It is based on contradictions, incomplete science, and unjustified extrapolations—failures that the new science has since begun to correct, but which nevertheless still hold sway in the public imagination. Let’s unpack this and, in the process, introduce the new science of complexity.

First of all, the classical reductionism of Newtonian physics was reversible; it didn’t matter in which direction you “ran the tape”—backwards or forwards—everything was just a matter of deterministic particles in motion.

However, both thermodynamics and evolution were different. They presented a model of reality quite contrary to this idea, with laws that had a direction. Entropy demanded a distinct “arrow of time,” and descent with modification meant that life was growing more and more varied with time.

Thus, despite being subsumed into the bleak modern worldview, these paradigms seemed to contradict some of its founding assumptions.

But if this were true, and the universe was irreversibly unfolding in some particular direction, which direction was it? Thermodynamics and evolution glaringly contradicted one another on this crucial point. One suggested the world was losing its usable energy and winding down towards the simple uniformity and homogeneity of equilibrium; the other, that the world was becoming ever more differentiated and elaborately structured—even in a “progress towards perfection.”

Well, which was it? Chaos or order? Inert sameness or dynamic novelty? What was the true ending to the cosmic story science was telling?

The resolution of this conundrum would only come with the transcendence of the reductionist paradigm altogether—a process set in motion towards the end of the 19th century, and only fully realized quite recently.

The Birth of Emergence

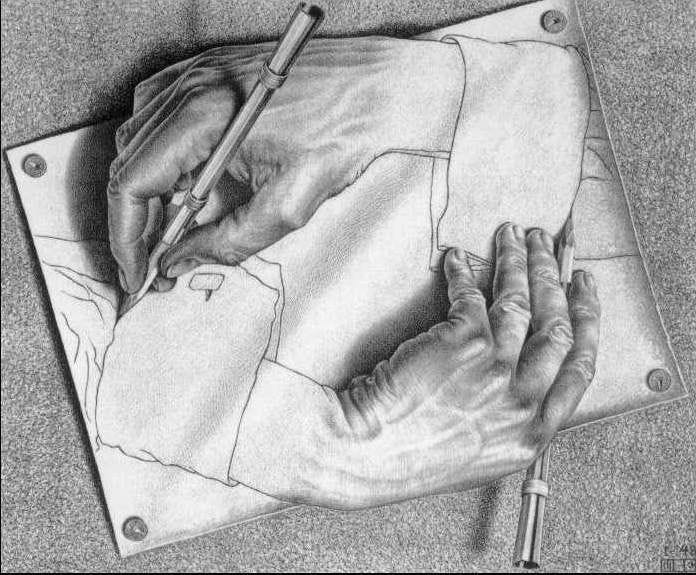

Reductionism, and the worldview it gave rise to, are predicated on the idea that we can understand reality best by isolating parts from the whole. By first analyzing the components, thought the pioneers of modern science, we can then work our way up to an understanding of the totality—because, after all, isn’t the whole just a sum of its parts?

Well, it just so happens: Nope, it’s not. It’s really, really not.

We know now something that the early scientists didn’t (and couldn’t): that when it comes to the more complex realities of nature, it’s not just about the parts and how they work by themselves. It’s just as much—if not more—about how the parts relate to one another.

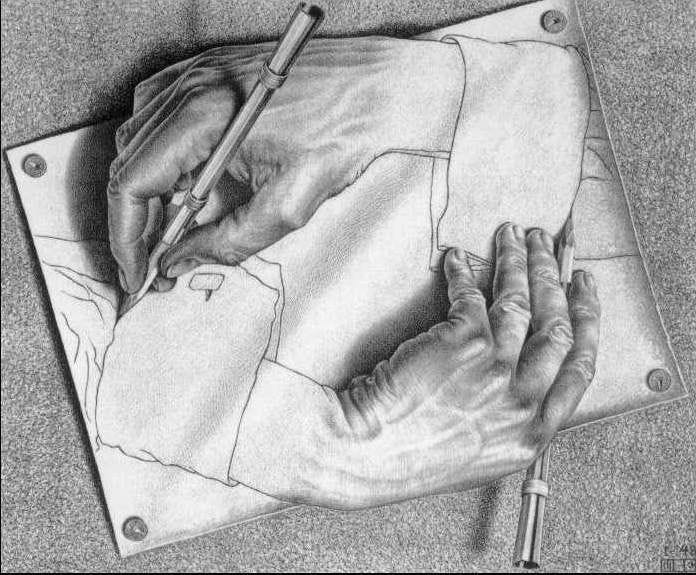

Wholes are made not only of parts, but of the relations of those parts. How one part works in concert with another part, and that one with another, and all of them together—those are dynamics that matter as much as the stuff of the parts themselves.

Wholes aren’t just things—they’re also processes.

Unfortunately, these inter-related dynamics are precisely what get lost when you break apart a whole and just consider its parts in isolation. Just as you’d destroy the life of an organism if you dissect it, so do you destroy some of the most vital aspects of genuinely novel wholes when you cut them up. Separation into parts destroys the connections, and the connections are what make it what it is.

In this way, the full truth of things lies, it turns out, in precisely what the early scientists did their best to systematically remove: relationality, interconnectivity—that is, complexity.

This is why it would take a science of complexity to fill in the gaps left by the reductionistic paradigm and fix the errors it introduced, even as that paradigm was itself an advance over the confused holism of traditional religion. But this would take some time to… well, emerge.

Eventually, though, as modern science progressed, and certain phenomena remained doggedly immune to reductionistic analysis (particularly life and mind), some influential thinkers began to take notice and theorize along the relational lines expressed above. They recognized that there was something that a consideration of parts alone failed to provide, and that reductionism had been missing a bigger picture.

The philosopher John Stuart Mill was one of the earliest such thinkers in this vein. Already in 1843, he presciently wrote in his book A System of Logic:

All organised bodies are composed of parts, similar to those composing inorganic nature, and which have even themselves existed in an inorganic state; but the phenomena of life, which result from the juxtaposition of those parts in a certain manner, bear no analogy to any of the effects which would be produced by the action of the component substances considered as mere physical agents. To whatever degree we might imagine our knowledge of the properties of the several ingredients of a living body to be extended and perfected, it is certain that no mere summing up of the separate actions of those elements will ever amount to the action of the living body itself.

Contrary to the assumption of the reductionists, Mill said, the whole is not just a sum of its parts. The behavior of life seemed to conform to principles that depended on the parts working holistically in concert, and thereby creating something truly novel.

Life and mind clearly presented problems for the reductionist view of science—problems future thinkers would attempt to resolve in this vein. In his 1874 book Problems of Life and Mind, the philosopher George Henry Lewes picked up Mill’s line of thought and extended it, coining a new term for the sort of phenomena Mill had put his finger on. He called them “emergents.” “Every resultant,” Lewes said,

is either a sum or a difference of the co-operant forces; their sum, when their directions are the same—their difference, when their directions are contrary. Further, every resultant is clearly traceable in its components, because these are homogenous and commensurable. It is otherwise with emergents, when, instead of adding measurable motion to measurable motion, or things of one kind to other individuals of their kind, there is a co-operation of things of unlike kinds. The emergent is unlike its components insofar as these are incommensurable, and it cannot be reduced to their sum or their difference.

So began the “British Emergentist” movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which included Lewes, as well as figures like Samuel Alexander, C. D. Broad, and Conway Lloyd Morgan. Their radical idea: emergent wholes are more than the sum of their parts. With this crucial insight, the British Emergentists would lay the groundwork for future theories of emergence, such as are today a mainstay of complexity science.

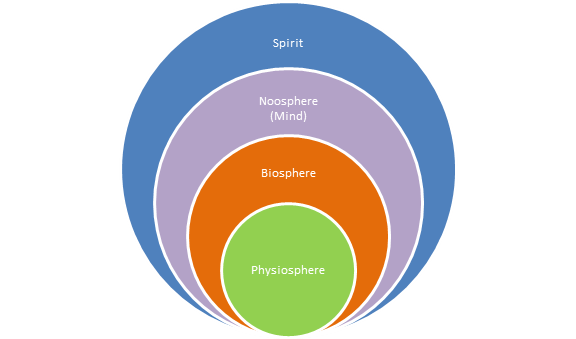

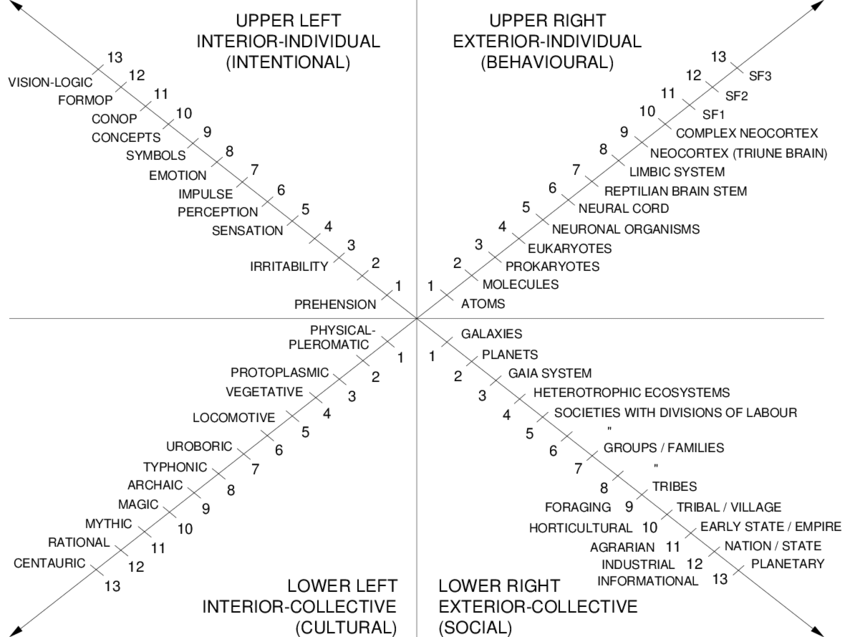

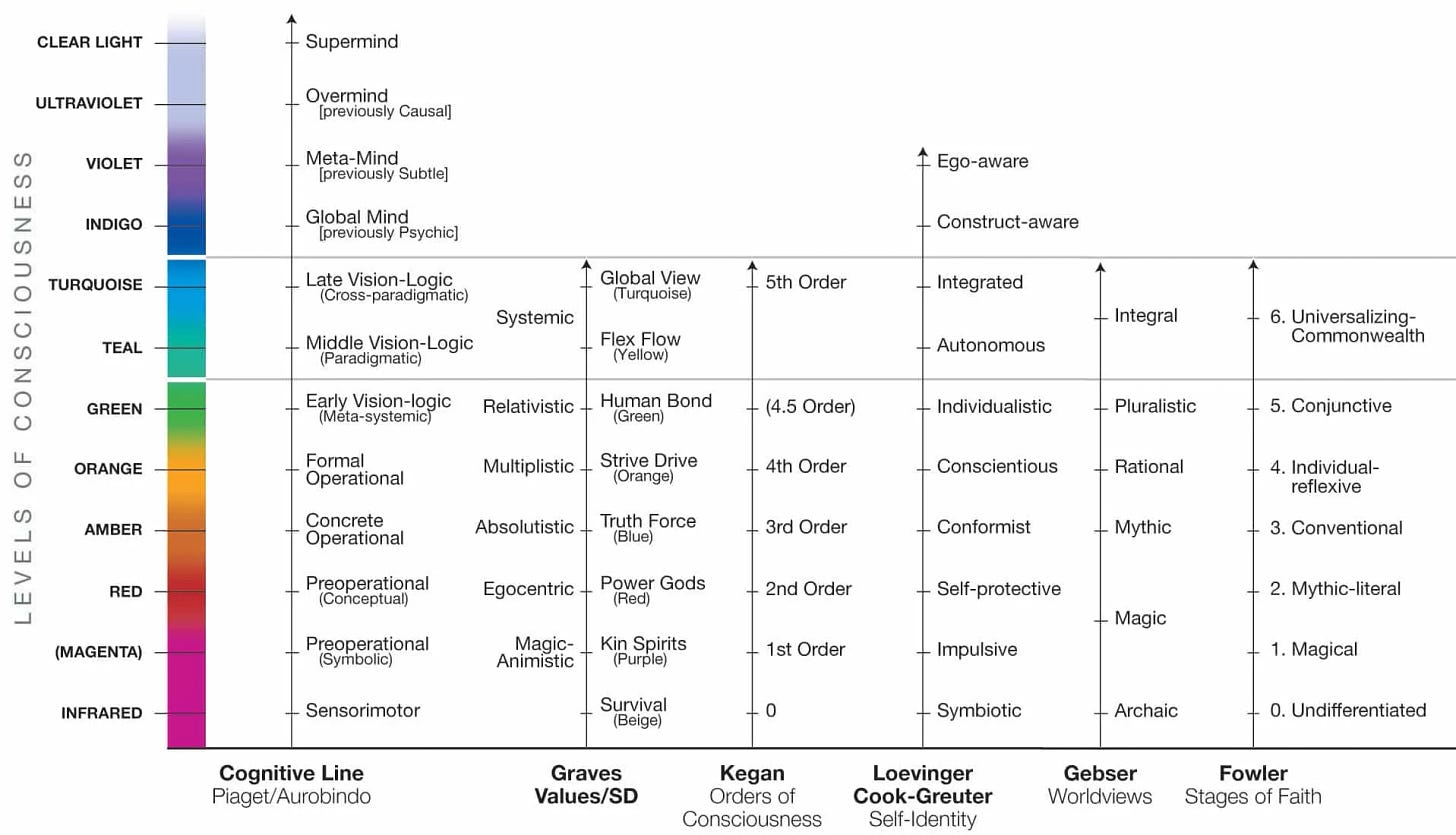

Recognizing that, in the case of emergents, wholes are more than the sum of their parts, it was clear that certain properties only pertain at certain levels of existence.

To use a common contemporary example, water is wet, but a single H2O molecule is not. Even though water is just a large collection of these molecules, the quality of wetness doesn’t arise until you reach the macro-scale. Zoom in and wetness disappears; zoom out and it emerges. “More is different,” a common refrain in emergence theory, means that more complexity in a system causes the qualities of its higher-level wholes to differ markedly (and often unpredictably) from those of its lower-level parts. The universe, it turns out, has different levels, and these different levels have their own laws.

The tiered, hierarchical nature of reality thus becomes an important aspect of emergence theory. Alexander, writing in his 1920 book Space, Time, and Deity, writes:

The emergence of a new quality from any level of existence means that at that level there comes into being a certain constellation or collocation of the motions belonging to that level, and this collocation possesses a new quality distinctive of the higher-complex. …The higher-quality emerges from the lower level of existence and has its roots therein, but it emerges therefrom, and it does not belong to that lower level, but constitutes its possessor a new order of existent with its special laws of behavior.

These “levels” emerge when more and more of reality is taken up and included together in deepening webs of relationship. That is how the universe complexifies through cosmic evolution. So Morgan stated in 1922, later published in his work Emergent Evolution, that just what emerges is precisely “some new kind of relation…at each ascending step.” Such a theory of new orders of reality implies, says Morgan:

(1) that there is increasing complexity in integral systems as new kinds of relatedness are successively super-venient; (2) that reality is, in this sense, in process of development; (3) that there is an ascending scale of what we may speak of as richness in reality; and (4) that the richest reality we know lies at the apex of the pyramid of emergent evolution up to date.

Perhaps this cosmic “pyramid” of “levels” and “ascending scales” is starting to sound a bit familiar? Despite taking a mortal blow from modern reductionism, was something like the “Great Chain of Being” (the metaphysical framework for holistic traditional religion) coming into focus in the Emergentist view of the world?

Despite similarities, there are also certainly crucial differences between these visions of a tiered cosmos. For one, the hierarchy of the early Emergentists was not value-based (evil to good), but complexity-based (simple to complex [“richness in reality”]). More importantly, there was no dualism here; the Emergentist hierarchy, though parting with reductionism, still allowed one to “keep the view that there is only one fundamental kind of stuff” as C. D. Broad put it in his 1925 book, The Mind and Its Place in Nature. This means that all scales remained natural, not supernatural—which leads to a fascinating implication: the “apex of the pyramid” here is not a supernatural Deity, but a natural (if emergent) “God.” So Alexander remarks in Space, Time, and Deity:

As actual, God does not possess the quality of deity but is the universe as tending to that quality… Thus there is no actual infinite being with the quality of deity; but there is an actual infinite, the whole universe, with a nisus [i.e., goal] toward deity… Deity is nisus and not an accomplishment.

We shall return to such fascinating implications for theology in the next chapter.

The British Emergentists had hit on a powerful idea, emergence, opening an entirely new metaphysical map of reality that could lead beyond reductionism. Unfortunately, timing is everything, as they say. And, as it happened, an explosion of discoveries in general relativity and quantum mechanics beginning in the early 20th century would effectively steal the show for the next generation of scientists, putting emergence on ice—at least until its big return in the 1980s, when complexity science would come fully into its own.

The Rise of Complexity Science

In the interim, from the 40s to the 60s, the effort to find a more scientifically rigorous holistic framework for life and mind continued with the development of new disciplines like cybernetics and general systems theory—key paradigms within the neo-holistic science of complexity.

As its founder, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, put it: “General system theory is a general science of ‘wholeness’ which up till now was considered a vague, hazy, and semi-metaphysical concept.” Cybernetics and general systems theory succeeded in breaking out of the limitations of the reductionist paradigm by considering the relational dynamics of complex systems, and pioneered important theoretical concepts like non-linearity, self-organization, and autopoiesis (or “self-construction”).

Key to von Bertalanffy’s systems-view of living organisms was the insight that they are decidedly not “closed systems,” such as the ones reductionistic scientists liked to study, but were in fact “open systems,” allowing free exchange of matter and energy with their environment. As he put it:

[T]he conventional formulation of physics are, in principle, inapplicable to the living organism being open system having steady state. We may well suspect that many characteristics of living systems which are paradoxical in view of the laws of physics are a consequence of this fact.

That is, life had escaped understanding in terms of classical physics precisely because it was, contrary to the “isolated systems” studied in fields like thermodynamics, connected to and in direct relationship with its environment by flows of matter and energy.

All of this would eventually lead to a truly revolutionary discovery—beginning a whole new field called non-equilibrium thermodynamics—which would contribute immensely to a radical re-conception of how energy behaves, and thus how life itself emerges and operates.

These paradigm-shifting breakthroughs were pioneered by a Belgian chemist named Ilya Prigogine. By Prigogine’s time, science had established clearly how energy behaves in closed systems: The fixed amount of energy dissipates, order and organization dissolve, and everything reaches a featureless, disordered balance called equilibrium. Such was entropy, whose increase was demanded according to the second law.

But, Prigogine wondered, what if the system isn’t closed, but opened up to a flow of energy? That is, let’s say we’re not looking at water in a closed thermos anymore, but a pan of water over a lit stove. How does the system behave now?

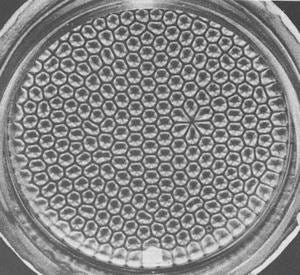

Simple as the idea was, the results were truly extraordinary. For, rather than spontaneously dissolving towards the disorder of equilibrium, the water in this scenario does the opposite: it spontaneously self-organizes, and

structure emerges!

Structures like this (called Bénard cells, after their original discoverer Henri Bénard) arise naturally, fueled by the energy flowing into the system. In fact—and here’s the amazing part—they arise precisely in order to dissipate that energy and generate the entropy demanded by the second law of thermodynamics! They emerge naturally because such configurations are simply more efficient at producing that entropy than more chaotic, disordered ones.

A much more familiar example of such a dissipative structure (as Prigogine called them) is the whirlpool that appears in your bathtub when you pull the stopper. This highly ordered spiral gyre emerges naturally and spontaneously as the result of countless water molecules self-organizing. Why? Because such a configuration actually allows the water to drain faster.

The natural tendency of the universe to seek balance and equilibrium can actually propel systems to become temporarily more ordered to achieve this end. That is, the same law that drives closed systems towards disorder and equilibrium actually drives open systems to generate order and complexity—and to remain “far from equilibrium,” in fact, as long as that flow of energy into the system persists.

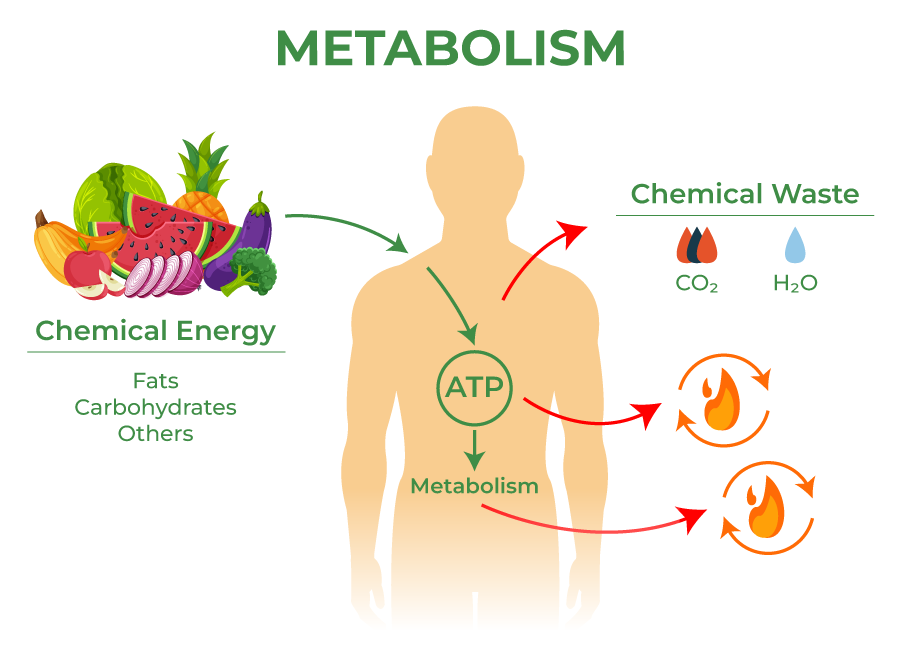

If this dynamic sounds familiar, it should. This is precisely the way that all living organisms operate, too! For life to accomplish all of the complex processes it must perform to resist entropy and stay highly ordered, it must be continually taking in new energy sources to metabolize.

Or, in terms more familiar to us: If you don’t eat, you die. Life is always in relational exchange with its environment—a complex, open system, in which the second law operates to facilitate self-organization, keeping it far from equilibrium (i.e., death).

This revolution in our conceptualization of thermodynamics has fueled a spate of discoveries related to the question of how life emerged in the first place.

In 2013, for instance, Japanese researchers showed that shining a light on silver nanoparticles caused them to spontaneously self-organize into more orderly configurations that could capture and dissipate the light’s energy more efficiently.

In 2017, Jeremy England of MIT published findings from computer simulations showing “dissipative adaptation,” in which molecules spontaneously self-organized into improbable configurations specifically adapted to the frequency of the energy source they were dissipating. The configurations that were maintained did so by outcompeting other possible configurations by more effectively producing entropy, suggesting a proto-Darwinian process of variation and retention in the struggle for energy consumption.

Evolution itself, then, can be understood in thermodynamic terms: specifically, as the goal of organisms to remain far from equilibrium. To do so requires them to effectively extract and dissipate free energy from the environment. Because energy resources (i.e., food) is limited, this competitive process fuels the Darwinian “struggle for existence,” in which successful organisms breed and unsuccessful ones are weeded, leading to further organization and the complexification of species.

Based on such discoveries, an additional law of thermodynamics has been proposed (first by Alfred Lotka and later by H. T. Odum) that includes the evolutionary implications of energy: “During self-organization, system designs develop and prevail that maximize power intake, energy transformation, and those uses that reinforce production and efficiency.”

Energy self-organizes matter into life, and life self-organizes by maximizing energy. Or, as complexity scientist Harold Morowitz put it, “The energy that flows through a system acts to organize that system.”

In this way, the dynamics of life became considerably clearer—not by looking at smaller and smaller parts (the way reductionism sought—and failed—to make sense of things), but by considering precisely the opposite: the relationship with the broader whole in which parts are embedded.

More than that, a consideration of how the whole is changing can inform our understanding of the parts. In this case, the whole is the universe itself and the parts are everything in it. The fact that the universe as a whole is expanding means that the second law does not require that everything one day end in heat death. This assumption was likely far too hasty. The great complexity scientist Stuart Kauffman summarizes this point in reassuring terms in his 2016 book Humanity in a Creative Universe:

The second law says free energy is running down. But we know now that the expansion of the universe is accelerating due to the mysterious dark energy that comprises about 70 percent of the energy of the entire universe. The implications of this accelerating expansion is that we do not have to worry about enough free energy. As the universe becomes larger, its maximum entropy increases faster than the loss of free energy by the second law, so there is always more than enough free energy to do work.

The takeaway? The initial conclusions scientists had drawn from the laws of thermodynamics were wrong: the universe was not destined only to grow more and more disordered with time. That idea arose on the false assumption that isolated systems could tell us everything we needed to know about energy.

But opening the system changes the whole story: energy also spontaneously organizes things—a revolutionary insight, considering that there are no truly isolated systems in nature! In the real world, everything is connected, everything is permeable, everything flows. Even that insulated thermos will dissipate its energy eventually. The universe is not a laboratory of isolated variables, but a tapestry of endlessly interweaving relations.

That is, after all, precisely what the early scientists were contending with, and did their best to systematically remove from the equation (literally). Today, bringing complexity back in is what is allowing us to understand reality better, and fix our sense of how the parts and the whole relate.

As Prigogine, who won the 1977 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his discoveries, put it:

[T]he importance we now give to the various phenomena we observe and describe is quite different from, even opposite to, what was suggested by classical physics. …The models considered by classical physics seem to us to occur only in limiting situations such as we can create artificially by putting matter into a box and then waiting till it reaches equilibrium.

But take nature out of the box, and entirely new laws come into play! The second law leads to order, not disorder, and the interconnected universe is seen for the continually self-organizing process it is.

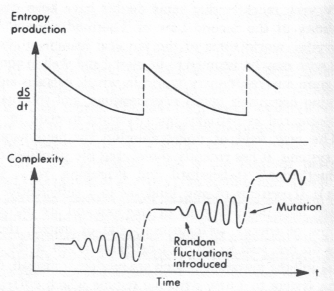

This self-organizing dynamic is a naturally cumulative, snowballing process that keeps building on itself—a process Prigogine called “order through fluctuation.” As energy pushes open systems farther from equilibrium, fluctuations in the energized system lead to threshold “bifurcation points,” at which the system is presented with novel, higher-order configurations as potential next stages of its evolution.

As systems scientist Erich Jantsch explains in his book The Self-Organizing Universe:

At each transition, two new structures become spontaneously available from which the system selects one. Each transition is marked by a new break of spatial symmetry. The path which the evolution of the system will take with increasing distance from thermodynamic equilibrium and which choices will be made in the branchings cannot be predicted. The further the system moves away from its thermodynamic equilibrium, the more numerous become the possible structures.

In this way, more and more complex structures evolve as energy flowing through the system naturally and spontaneously pushes it ever onwards, toward increasingly novel forms. The universe organizes itself.

With these insights (still unknown to many in the general public even today), the apparent conflict between thermodynamics and evolution was resolved. There was indeed an arrow of time, and the question of which direction it was heading in was clear.

Evolution had suggested an increase in novelty, diversity, and complexity; now, thermodynamics agreed. More than that, it actually helped explain why and how complexification occurs, by linking the evolutionary process to free energy and emergent self-organization.

In this way, evolutionary development was no longer something unique to life, but a process that could be expanded to include less complex matter, too. In his book Cosmic Evolution: The Rise of Complexity in Nature, Eric Chaisson writes:

Life is an open, coherent, spacetime structure maintained far from thermodynamic equilibrium by a flow of energy through it—a carbon-based system operating in a water-based medium, with higher forms metabolizing oxygen. Although the second part of this definition pertains to the living state as we know it, the first part could well apply to a galaxy, star, or planet… And that is the crux of our argument: Life likely differs from the rest of clumped matter only in degree, not in kind.

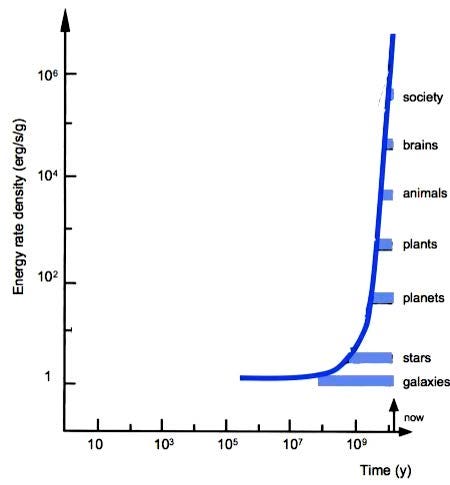

The degree to which it differs is one of complexity—for which Chaisson employs a specific metric, one that can be used to measure the complexity of anything from stars to living organisms: free energy rate density.

As systems theorist Ervin László summarizes it in his pioneering book Evolution: The Grand Synthesis:

Free-energy flux density is a measure of the free energy per unit of time per unit of mass: for example, erg/second/gram. A complex chemical system retains more of this factor than a monatomic gas; a living system retains more than a complex chemical system. This indicates a basic direction of evolution, an overarching sweep that, together with the decrease of entropy and of equilibrium, defines the arrow of time in the physical as well as in the biological and the social world.

Free energy flows through systems, organizing them into more orderly configurations. Order builds upon order, and complexity mounts—until whole new emergent levels appear, like life from matter. In this way, complexity is really just a measure of how energy organizes matter—something it has been doing to exponentially greater degrees as time passes.

In Cosmic Evolution, Chaisson charts this evolutionary increase in free energy rate density, offering a compelling visualization of the complexification of the universe to date:

In this way, the entire cosmos has been evolving—matter naturally self-organizing into stable forms through the flow of energy, leading to life, and life evolving through natural selection, leading to still more complex species.

As it does, something else emerges: agency. Work by complexity researchers like Sara Walker, George Ellis, Giulio Tononi, Erik Hoel, and others has shed considerable light on the way more complex organisms come to exhibit causal power on their lower-level constituent parts. Such causal emergence repudiates the old deterministic account of organisms as being nothing but particles in motion. Rather, it shows that information generated at higher levels can have a causal effect on its material substrate. In this way, there is not only “bottom-up” causation from particles, but also “top-down” causation, as information encoded in patterns of organization at the macro-level works to direct material particles at the micro-level towards specific states and goals.

Such causal emergence appears for the first time in earnest with the origin of life, as information in the genome is able to supervene over the molecular and atomic level, leveraging the parts towards the aims of the biological whole. This sort of agency gains entirely new levels of causal freedom and power, however, with the rise of more complex minded animals. In this way, the self-consciousness such as human beings exhibit can be understood as a uniquely complex form of causal emergence, whereby activity at the mental level exerts itself over and above the activity of the body. In this way, the will itself emerges. We are, then, not just determined automatons the way reductionists like Laplace envisioned, but genuinely free agents with self-determination, whose choices matter.

In sum, with the implications becoming clear from this profound paradigm shift in the sciences, we now find ourselves facing an entirely new cosmic story, a mind-bending vision in which the universe has been, of its own accord, bringing all things together in more novel and intricate forms, producing order spontaneously from its originally featureless chaos in an uninterrupted evolutionary process that has led from unconscious, deterministic material at the lowest level to self-conscious agents with free will at higher levels.

Far from being a depressing dissolution or undirected slog of “frisky dirt” evolving nowhere, there is, we now see, a great epic of complexification underway, the “epic of evolution” as Chaisson calls it, as new wholes emerge, interact in new webs of relation, and then form parts in even higher-level wholes, such as lead to subjectivity, self-awareness, and free will.

Okay, but what is the real significance of all this? What is this grand story of complexification really telling us? What does it reveal about the nature of reality and our place in it? Now that we have traced some of the historical context, showing how knowledge advanced from a pre-scientific religious holism, to the primitive science of reductionism, and onwards still to a neo-holistic science of complexity, we can finally consider what all of this really means in the broadest terms. For that, we must turn to some unifying theories that bring it all together.

Emergentism: there is no chapter 7