Reviewing “The Deconstruction of

Christianity”

In their book The Deconstruction of Christianity, Alisa Childers and Tim Barnett help readers “stand your ground and respond with clarity and confidence” in the face of deconstruction.

In what follows, I review the book. Overall, I find it unhelpful. But there are a few aspects I like.

Apostasy

The book starts on a sour note: the first word is “apostasy.” Readers like me will immediately wonder if this book aims to help those asking hard questions or defend the Christian faith against the “heretics.” In many ways, it opts for the second. The opening pages are not welcoming.

Childers and Barnett didn’t write this book for questioning people who are deconstructing. It’s for the friends and family of deconstructors. It’s “primarily written for Christians who are experiencing deconstruction from the outside.” The authors’ goal is to “walk you through what deconstruction is and how it works, and give you practical advice on how to relate with friends and loved ones going through it.” (6)

The authors acknowledge some people see deconstruction as compatible with Christianity. Childers and Barnett disagree. “Deconstruction is as old as humanity itself,” they say. “It began with Satan—the father of faith deconstruction—and continues today.” (47 ) In fact, “people have been abandoning the standard of God’s Word and engaging in a process of rethinking—and often abandoning—their faith since the beginning.” (61)

It’s Ultimately About Authority

This book has many problems, and I’ll list some later. As I see it, the fundamental problems are two:

1. The authors want a fully trustworthy authority (the Bible).

2. The authors think Christians must choose between the Bible as that authority and the authority of the individual person.

“The heart of the deconstruction explosion is a rejection of biblical authority,” say Childers and Barnett bluntly. (26) The Bible provides truths that the method of deconstruction and deconstructors abandon.

Appealing to the Bible as the only trustworthy authority won’t convince those who deconstruct, of course. Most (rightly) doubt that the Bible is fully reliable, saying it is neither inerrant nor infallible. Childers and Barnett dismiss this doubt, in part, by saying deconstructors have shallow faith, are rebellious, fight on the wrong side of a spiritual battle, follow culture instead of Christ, are captive to Satan, get seduced by vain philosophy, are broken and sinful, and so on (see chapter 10 and elsewhere).

At least in this book, the authors don’t address realities that undermine belief in the absolute authority of the Bible. They don’t address people like me and others who 1) know the many errors and discrepancies in scripture, 2) know the original languages and differences between the oldest known biblical manuscripts, and 3) know that biblical passages receive a wide variety of plausible interpretations.

Objective vs. Subjective Truth?

Childers and Barnett believe Christians face an either/or choice when it comes to truth. They can 1) place their trust in the Bible, which is an external authority. Or 2) trust themselves and their own subjectivity.

The Bible “communicates objective truth that isn’t meant to be interpreted subjectively,” the authors claim (34). In the deconstruction movement, “biblical interpretation becomes subjective.” (35) “Deconstruction isn’t just about questioning beliefs,” they say, “it’s about rejecting Scripture as the source of objective truth and authority.” (121) Deconstructors reject God’s Word.

This objective vs. subjective scheme, however, makes little sense. Long before “deconstruction” was a word in the academy or popular culture, people realized no one has a fully objective, unbiased, and uninfluenced perspective. Histories, cultures, perspectives, preferences, biology, and feelings influence those who read the Bible. Because personal subjectivity inevitably influences our interpretations, good and wise people interpret scripture in ways.

Sometimes those in the deconstruction community encourage people to “make up their own minds,” instead of following a church, pastor, or influencer. But this doesn’t mean people are entirely free of influence from others. We’re always affected by forces, factors, ideas, and actors external to ourselves. Objective causes influence our subjectivity; interpretations have external influences.

People like Jacques Derrida are right when they say that words—including biblical words — have no timeless and absolute meaning. But you don’t have to be a philosopher to know this: just look at how many biblical translations and interpretations are present today and throughout history. A more accurate view says objective factors outside ourselves always affect our subjectivity. And one of those factors may or may not be the Bible.

Authoritative Mindset

Two overarching issues came repeatedly to mind as I read The Deconstruction of Christianity. The first has to do with what in cognitive science is called the “Authoritative” mindset. Childers and Barnett write from it, and their frequent appeals to biblical authority illustrate this.

Cognitive sciences describe three primary mindsets among people at least in the West: Authoritative, Nurturant, and Permissive. Evangelicals like Childers and Barnett typically operate from the Authoritative mindset. They need authorities more than most people. So Authoritatives put their confidence in a book (Bible), group (church or denomination), leader (pastor), government (USA), or person (Donald Trump). They also prize obedience, order, certainty, hierarchies, coercion, and more.

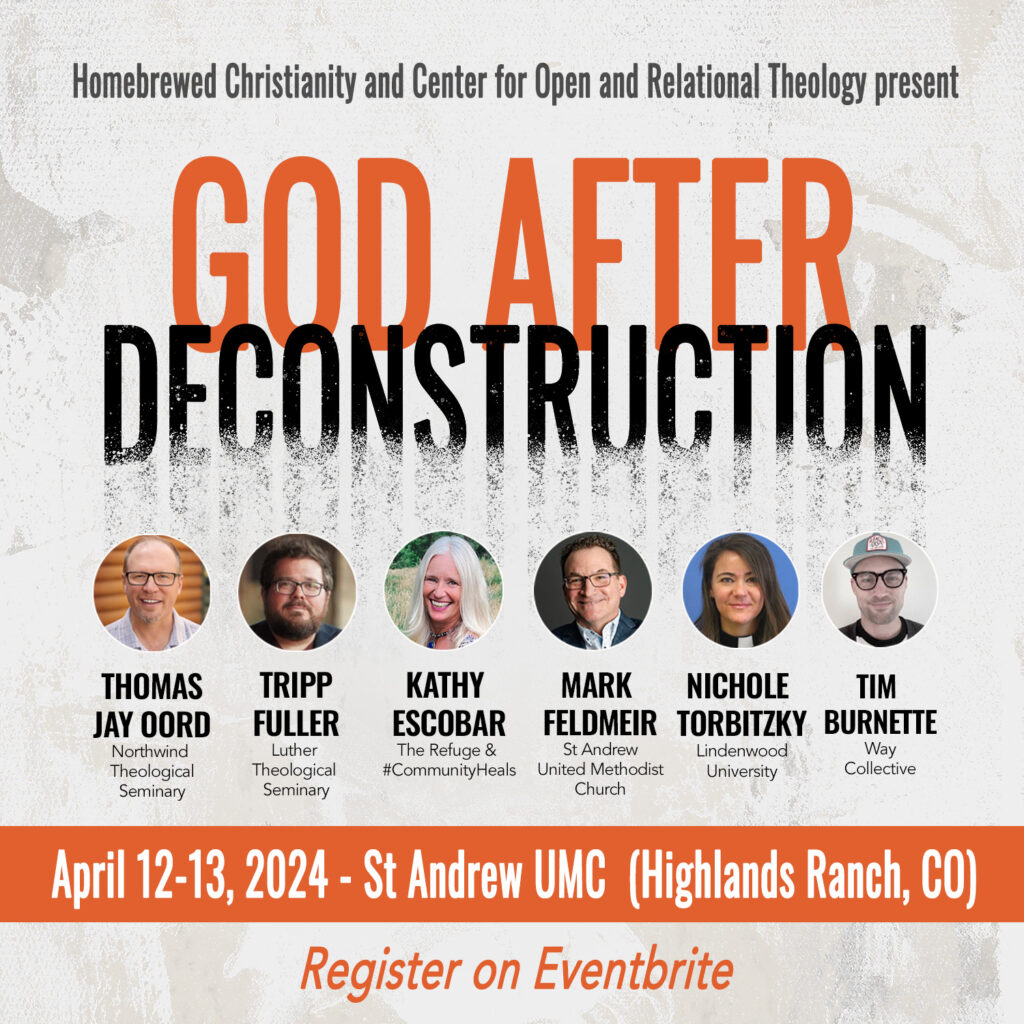

As I read The Deconstruction of Christianity, I found oodles of evidence that Childers and Barnett operate from an Authoritative mindset. Deconstruction annoys them because it does not. In God After Deconstruction (coming out in April 2024), Tripp Fuller and I argue that the Nurturant mindset better reflects the message of Jesus. Sociological studies show that those with a Nurturant mindset are healthier in various ways than those with Authoritative mindsets. They also live well without the strong need for external authorities.

Complexity Stage

The second theme continually coming to my mind as I read Childers and Barnett is what many call the “stages of faith.” Brian McLaren offers a rubric with four stages and names them “simplicity,” “complexity,” “perplexity,” and “harmony.”

Childers and Barnett fit nicely in the complexity stage. Like simplicity people, they seek clear categories of black and white, us and them, in and out, right and wrong. The authors make strong distinctions between Christ vs. the world, church vs. culture, and scriptural truth vs. societal opinions. But unlike simplicity people, Childers and Barnett offer sophisticated versions of these distinctions, realizing there must be some nuance.

Those who deconstruct fit in either the perplexity or harmony stages of faith. The connection between deconstruction and perplexity will be obvious. But even in the harmony stage, the methods of deconstruction are not abandoned. Harmony people recognize the falsity of strict binaries, in part, because they cannot capture well the God present to and revealing in all creation.

Should Christians Question?

Childers and Barnett repeatedly tell their readers that questioning is normal and has always been part of the Christian faith. Christians should ask questions about the Bible, God, and life. Test the Bible, they say, and the church.

But the questioning Childers and Barnett advocate can’t get too radical. We should not question the ultimate authority: “God’s Word” (or what is better called “Christian scripture”). Questioning harms if it undermines this ultimate standard for truth. Some who ask questions are really just looking for ways to exit the faith.

Although deconstruction is bad, reformation is good. According to the authors, “reformation is the process of correcting mistaken beliefs to make them align with Scripture.” (125) Notice the priority of the Bible again. The message: question… but don’t abandon scripture.

To return to McLaren’s faith formation language, Childers and Barnett seem to encourage questioning if it moves the Christian from a simplistic faith to a complex one. But questioning that might move the person toward perplexity and harmony goes too far. Such questioning might, and usually does, undermine trust in the Bible as fully trustworthy. And it might lead people to doubt doctrines the authors consider essential, even the existence of God.

To illustrate his willingness to entertain tough questions, Tim Barnett briefly brings up the problem of evil. The authors earlier (rightly) noted that questions about evil are the primary reasons people deconstruct. When asked why God doesn’t stop evil, Barnett says, “I don’t know.” He doesn’t have an answer to why God sometimes permits evil, but other times intervenes. He knows this isn’t satisfying, but he’s trying to be honest.

I wonder why the Bible—Barnett’s authoritative source and “God’s Word”—doesn’t provide an answer to the problem of evil that satisfies him. To the #1 question asked by people who deconstruct, why doesn’t the alleged ultimate authority offer a satisfying answer? Barnett thinks the Bible’s clear about issues like penal substitutionary atonement, although that issue keeps far fewer people up at night.

Despite the encouragement to ask some questions, The Deconstruction of Christianity claims that those who deconstruct are deceived, rebellious, disingenuous, etc. See the list above. This encouragement rings hollow.

Reasons to Deconstruct

In the first half of the book, Childers and Barnett address reasons people deconstruct. They don’t offer answers to these issues. And they give mixed messages.

At one point, the authors claim that “most people don’t make a conscious choice to enter into deconstruction.” This fits the experience of most people I know. The authors say that deconstruction is “often triggered by a crisis that initiates the process. It’s typically not something people choose. In many cases, it happens to them.” (78) Elsewhere, however, the authors blame deconstruction on “rebellion against God” (193).

Among the reasons people deconstruct, the authors list suffering, doubt, politics, purity culture, the Bible, toxic theology, and abuse. They don’t offer rejoinders for these reasons. And they say that people of shallow faith struggle with them. The message seems to be those who truly trust the Bible can handle issues that might tempt other people to deconstruct.

Childers and Barnett insist that abuse and injustice are not reflections of Christian doctrines. “There certainly are valid examples of abuse in the church, such as sexual assault and abuses of power,” they say. “But many deconstructionists go further, saying that some historic orthodox teachings of Christianity—such as penal substitutionary atonement, the doctrine of hell, and complementarianism—are abusive by nature.” (96)

Although the authors preach the importance of good theology, they will not admit that some of what they consider “historic orthodox teachings” leads people to deconstruct.

Toxic Theology?

In a chapter titled “Toxic,” Childers and Barnett further address the claim that traditional Christian practices and doctrines sometimes harm. These claims about harm draw primarily from research in sociology and history, they say, rather than Scripture.

Beth Allison Barr’s book The Making of Biblical Womanhood garners the authors’ attention. Barr argues that Christian views have often harmed women and restricted them from some roles. Childers and Barnett also cite Kristin Kobes DuMez’s work on Christian nationalism as an example of history and sociology trumping theology.

The authors say arguments like Barr’s and Kobes DuMez’s begin by identifying a problem in society. Then they show how the church endorsed or allowed this problem. Finally, they argue that theology (especially white evangelical theology) should be rejected or reimagined.

Because Barr and Kobes DuMez address women’s issues, I was eager to see how Childers and Barnett would respond. I assumed the authors would give an argument for complementarity. Instead, they say, “The extent to which women can take part in church leadership roles has been hotly debated among faithful Christians for millennia. The point… is not to settle the correct biblical teaching on the topic.” Instead, they argue that history and sociology cannot “discover true doctrines and rule out harmful, false ones.” (150)

To settle disputes about the role of women and how they’ve been harmed, say the authors, we need “an objective standard to appeal to. This requires the Bible.” They add that “while neither of the authors of this book would fault someone for coming to an honest position on biblical grounds regarding the egalitarian vs. complementarian debate, we would fault someone for rejecting complementarianism simply because they didn’t like where those Bible passages lead.” (150)

Not the Bible Alone

In their discussion of Barr and DuMez, Childers and Barnett are blind to the problem they’ve created.

If “honest” people can come to differing views about gender roles while studying the “objective standard” of the Bible, that standard isn’t the clear authority needed to decide this issue. Childers and Barnett seem to admit that the Bible is open to more than one legitimate interpretation of what it says about women. This means other standards are needed.

Barr, Kobes DuMez, and others cite sociological, historical, psychological, and even medical data as offering apparent fruits of various Christian practices and doctrines. They’re pondering the consequences of particular beliefs and practices and making strong cases that some produce bad fruit. And because the Bible can be interpreted in various ways, we need other sources for deciding which beliefs and practices are healthy or true and which are not.

The role of women is just one among many issues in which the Bible cannot be the sole resource for Christian doctrines and practices. The need for multiple sources applies also to questions of sexuality.

In fact, I laughed out loud when I read the “Homophobia” section of the book. Childers and Barnett say that Scripture describes sexual immorality as any act of sex other than “between one man and one woman in the context of marriage.” This is laughable! Don’t they know about Solomon’s wives? Or are only some passages of the Bible authoritative on this issue? I laughed again when they wrote, “It’s not just a few so-called ‘clobber’ passages that teach this. It’s the narrative of Scripture cover to cover.” (37) What Bible are they reading?

What I Liked

There wasn’t much I liked in this book. But here are some in bullet form:

* I liked the authors’ empathy for family and friends of those who deconstruct. Of course, I think the lion’s share of empathy should go to deconstructors. The authors express relatively little of that compared to criticisms. But Childers and Barnett rightly note the anguish that parents and friends of those who deconstruct sometimes endure. It’s painful to teach a child your cherished beliefs, only to have that child call them harmful. To illustrate this point, Childers and Barnett write, “When deconstruction leads to a rejection of faith, that can feel like a death both to the one deconstructing and to their loved ones.” (66) They’re right.

* The authors quoted books and social media from some of the leading voices in deconstruction. Sometimes critics ignore what their opponents actually say. While Childers and Barnett made some missteps, I thought they were pretty good overall. I even found a few sources for the book Tripp and I are writing!

* The authors believe ideas matter. Like me, they think theology makes a difference, because our views of reality make a difference. While I disagree radically with many of their theological claims, I appreciate their dedication to exploring ideas, their truth and impact. Theology is more than sociology.

* I think critical race theory and its reflection on power should be one tool in social analysis. I affirm it. But I agree with the authors that sometimes those who use critical race theory put all their cards on issues of power without addressing issues of truth. Most times, the two overlap. But I think both must be addressed.

Conclusion

My notes on this book extend far beyond what I have written here. Although I disagree fundamentally with the authors and disagree on most points of the book, I’m glad I read it.

This book also helped with writing the book Tripp Fuller and I are doing called, God After Deconstruction. If these issues interest you, I hope you consider buying a copy when it comes in April 2024. And here’s a graphic for the upcoming Denver conference on the subject.

No comments:

Post a Comment