Sumer was one of the three original civilizations, along with the Indus Valley Civilization and Egypt.The religion of Sumer was first adopted by Akkad, which caused it to spread to Assyria, Ugarit and from there to Canaan.After that, it was adopted by the Babylonians, and the Assyrians again inherited it from Babylon. It seems the Hittites also took parts of it to Anatolia, and it spread as far as Greece.- Quora / Steve Page

What are the main differences between Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian mythology, if any?

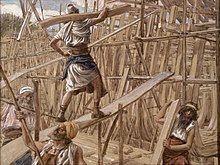

This video features a brief talk on Ziusudra or Utnapishtim and the Flood in Sumerian and Babylonian mythology. The Mesopotamian story bears many similarities to Noah and the Ark in the Bible, in the Book of Genesis.

|

| amazon link |

Blurb

The ancient civilization of Mesopotamia thrived between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates over 4,000 years ago. The myths collected here, originally written in cuneiform on clay tablets, include parallels with the biblical stories of the Creation and the Flood, and the famous Epic of Gilgamesh, the tale of a man of great strength, whose heroic quest for immortality is dashed through one moment of weakness.Recent developments in Akkadian grammar and lexicography mean that this new translation--complete with notes, a glossary of deities, place-names, and key terms, and illustrations of the mythical monsters featured in the text--will replace all other versions.About the Series: For over 100 years Oxford World's Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford's commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

|

| Sumeria's Pantheon of gods |

|

Ziusudra (Sumerian: 𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺) was a figure that appeared in a Sumerian king list as well as the flood myth known as the the "Epic of Ziusudra." |

|

| Noah's ark, 12th-century fresco in the nave of the church at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, Fr. |

In today's video, we examine the genesis and development of one of the world's oldest mythological figures, the legendary King of Uruk, Gilgamesh, and the Epic that bears his name. Along the way we'll explore over 2000 years of history, culminating in an examination of the origins of the Mesopotamian flood myth, which continues to echo in modern religions to this day.This video owes a special thanks to archaeologist Dr Geoff Emberling, who kindly allowed me to use a number of his photos of Iraq. You can find more information on his research activities in the links below:

GENESIS FLOOD NARRATIVE

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is a Hebrew flood myth.[1] It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre-creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microcosm of Noah's ark.[2]

The Book of Genesis was probably composed around the 5th century BCE,[3] although some scholars believe that Primeval history (chapters 1–11), including the flood narrative, may have been composed and added as late as the 3rd century BCE.[4] It draws on two sources, called the Priestly source and the non-Priestly or Yahwist,[5] and although many of its details are contradictory,[6] the story forms a unified whole.[7]

A global flood as described in this myth is inconsistent with the physical findings of geology, archeology, paleontology, and the global distribution of species.[8][9][10] A branch of creationism known as flood geology is a pseudoscientific attempt to argue that such a global flood actually occurred.[11] Some Christians have preferred to interpret the narrative as describing a local flood, instead of a global event.[12]

Summary

The story of the flood occurs in chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible. Ten generations after the creation of Adam, God saw that the earth was corrupt and filled with violence, and he decided to destroy what he had created. But God found one righteous man, Noah, and to him he confided his intention: "I am about to bring on the Flood ... to eliminate everywhere all flesh in which there is the breath of life ... ." So God instructed him to build an ark (in Hebrew, a chest or box), and Noah entered the Ark in his six hundredth year [of life], and on the 17th day of the second month of that year "the fountains of the Great Deep burst apart and the floodgates of heaven broke open" and rain fell for forty days and forty nights until the highest mountains were covered to a depth of 15 cubits, and all life perished except Noah and those with him in the Ark. After 150 days, "God remembered Noah ... and the waters subsided" until the Ark rested on the mountains of Ararat, and on the 27th day of the second month of Noah's six hundred and first year the earth was dry. Then Noah built an altar and made a sacrifice, and God made a covenant with Noah that man would be allowed to eat every living thing but not its blood, and that God would never again destroy all life by a flood.[13]

Composition

The consensus of modern scholars is that Genesis was composed around the 5th century BCE,[3] but as the first eleven chapters show little relationship to the rest of the book, some scholars believe that this section (the so-called Primeval History) may have been composed as late as the 3rd century BCE.[4]

It is generally agreed that the history draws on two sources, one called the Priestly source, the other non-Priestly or Yahwist,[5] and their interweaving is evidenced in the doublets (i.e., repetitions) contained within the final story.[14] Many of these are contradictory, such as how long the flood lasted (40 days according to Genesis 7:17, 150 according to 7:24), how many animals were to be taken aboard the ark (one pair of each in 6:19, one pair of the unclean animals and seven pairs of the clean in 7:2), and whether Noah released a raven which "went to and fro until the waters were dried up" or a dove which on the third occasion "did not return to him again," or possibly both.[6] But despite this disagreement on details the story forms a unified whole (some scholars see in it a "chiasm", a literary structure in which the first item matches the last, the second the second-last, and so on),[a] and many efforts have been made to explain this unity, including attempts to identify which of the two sources was earlier and therefore influenced the other.[7] Some scholars have even questioned whether the story is actually based on two different sources, noting that some of the doublets (such as the dove and raven) are not actually contradictory and in fact appear as linked motifs in other biblical and non-biblical sources, that the method of doublets is inconsistently applied in that the alleged sources themselves contain doublets, and that the theory assumes a redactor who combined the sources inconsistently (in some cases extensively editing together the text and in some cases faithfully preserving contradictory versions) for unclear reasons.[15] Similarly, the complete Genesis flood story matches the parallel Gilgamesh flood story in a way which neither of the proposed biblical sources does.[16]

Sources

The following table compares the proposed Yahwist and Priestly sources.[17] Each provides a complete story-line, with introductions and conclusions, reasons for the flood, and theologies.[18]

| Verses | Yahwist (or non-Priestly) | Priestly |

|---|---|---|

| 6:5–8 | Introduction: humanity's wickedness, God regrets creating, announces decision to destroy; Noah's righteousness. | |

| 6:9–22 | Introduction: Noah's righteousness, humanity's wickedness, God's decision to destroy; Ark described, Covenant described, 1 pair of all animals, Noah does as God commands. | |

| 7:1–5 | 7 pairs of clean animals, 1 pair unclean; 7 days to gather animals; Noah does as God commands. | |

| 7:6 | Noah's age: 600 years | |

| 7:7–10 | Noah enters Ark with animals after 7 days | |

| 7:11 | Year 600, month 2, day 17: firmament breaks, waters fall from above and rise from below. | |

| 7:12 | Rains 40 days and 40 nights. | |

| 7:13–16a | Noah and family and animals enter Ark on same day as flood begins. | |

| 7:16b–17a | Flood lasts 40 days and nights. | |

| 7:18–21 | Waters rise, all creatures destroyed. | |

| 7:22–23 | All creatures destroyed. | |

| 7:24–8:5 | Flood lasts 150 days; God remembers Noah, fountains and floodgates closed, waters recede; Month 7 day 17, Ark grounds on mountains of Ararat. | |

| 8:6–12 | After 7 days Noah opens window, sends out raven, dove, dove, 7 days between flights | |

| 8:13–19 | Year 601, month 1, day 1: Noah opens cover; ground begins to dry; Month 2, day 27, dry land appears, Noah and family and animals exit, animals begin to multiply | |

| 8:20–22 | Noah builds altar, sacrifices clean animals, God smells sweet aroma, promises not to destroy again. | |

| 9:1–17 | Noah and family told to multiply, given animals to eat; Covenant established, rainbow as sign, God promises not to flood again. |

Comparative mythology

Scholars believe that the flood myth originated in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1880–1595 BCE) and reached Syro-Palestine in the latter half of the 2nd millennium BCE.[19] Extant texts show three distinct versions, the Sumerian Epic of Ziusudra, (the oldest, found in very fragmentary form on a single tablet dating from about 1600 BCE, although the story itself is older), and as episodes in two Akkadian language epics, the Atrahasis and the Epic of Gilgamesh.[20] The name of the hero, according to the version concerned, was Ziusudra, Atrahasis, or Utnapishtim, all of which are variations of each other, and it is just possible that an abbreviation of Utnapishtim/Utna'ishtim as "na'ish" was pronounced "Noah" in Palestine.[21]

Numerous and often detailed parallels make clear that the Genesis flood narrative is dependent on the Mesopotamian epics, and particularly on Gilgamesh, which is thought to date from c.1300–1000 BCE.[22]

Flood chronology

Numbers in the Bible often have symbolic or idiomatic meaning, and the 40 days and nights for which rain fell on the Earth indicates a complete cycle.[23]

The flood begins on the 17th day of the second month when "the springs of the great deep burst forth, and the floodgates of the heavens were opened", and after 40 days the ark floats (Genesis 7:11–12). The waters rise and then recede, and on the 17th day of the seventh month (or the 27th day in the Greek version) the ark rests on the mountains (Genesis 8:4). The waters continue to fall, the ark is uncovered on the 1st day of the 1st month of Noah's 601st year, and is opened on the 27th day of his 601st year (Genesis 8:13–14).[24]

The period from the beginning of the flood to the landing on the mountain is five months (the second month to the seventh, Genesis 7:11 and 8:4) and 150 days (8:3), making an impossible five months of 30 days each; the number is schematic, and is based on the Babylonian astronomical calendar of 360 days (12 months of 30 days each).[25] This means that the flood lasts 36 weeks according to the flood calendar, in which an extra day is added to every third month.[26] The number of weeks is symbolically significant, representing the biblical cypher for destruction (the number 6, expressed as 6x6=36), while the number 7 (the number of days in a week) represents the persistence of creation during this time of destruction.[27]

The period while the ark is afloat, i.e. the period during which the Earth is entirely covered by water, represents a gap in time, as is confirmed by the strange details of the ages of Noah and Shem.[24] Noah is 600 years old when the flood comes (Genesis 7:6); it ends in his 601st year (Genesis 8:13), and he then lives another 350 years before dying in his 950th year (Genesis 9:28–29); the year taken up by the flood is not counted.[24] Similarly his son Shem is 100 years old on entering the ark (Genesis 7:6) and still 100 years old on fathering Arpachshad two years after the flood (Genesis 11:10).[24]

Scholars have long puzzled over the significance of the flood lasting one year and eleven days (day 17 of year 600 to day 27 of year 601); one solution is that the basic calendar is a lunar one of 354 days, to which eleven days have been added to match a solar year of 365 days.[28]

The "original", Jahwist narrative of the Great Deluge was modest; a week of ostensibly non-celestial rain is followed by a forty-day flood which takes a mere week to recede in order to provide Noah his stage for God's covenant. It is the Priestly source which adds more fantastic figures of a 150-day flood, which emerged by divine hand from the heavens and earth and took ten months to finally stop. That the Jahwist source's capricious and somewhat simplistic depiction of Yahweh is clearly distinguished from the Priestly source's characteristically majestic, transcendental, and austere virtuous Yahweh.[29]

The Priestly flood narrative is the only Priestly text that covers dates with much detail before the Exodus narrative. This is perhaps due to a version of the flood myth that was available at the time. There is a text discovered from Ugarit known as RS 94.2953, consisting of fourteen lines telling a first-person account of how Ea appeared to the story's protagonist and commanded him to use tools to make a window (aptu) at the top of the construction he was building, and how he implemented this directive and released a bird. Antoine Cavigneaux's translation of this text made him propose that this fragment belongs to a Mesopotamian flood myth, perhaps Atrahasis or Tablet IX of Gilgamesh, which has a version found in Ugarit (RS 22.421) that contains a first person account of the flood. If this suggestion is correct, then RS 94.2953 represents a unique version of the Mesopotamian flood story. Line 1 of the text says "At the start of the time of the disappearance of the moon, at the beginning of the month". This reference to the lunar date giving the specific date the protagonist released the bird is significant as it is the only variant of the flood story giving a specific date and the rest do not attribute specific dates or calendrical details to the various stages of the flood. Both RS 94.2953 and Genesis 8 are about the flood protagonist releasing a bird on a specific calendrical date in order to find land in the midst of the flood.[30]

Theology: the flood and the creation narrative

The primeval history is first and foremost about the world God made, its origins, inhabitants, purposes, challenges, and failures.[31] It asks why the world which God has made is so imperfect and of the meaning of human violence and evil, and its solutions involve the notions of covenant, law, and forgiveness.[32] The Genesis creation narrative (Genesis 1–2) deals with God's creation and God's repentance is the rationale behind the flood narrative, and in the Priestly source (which runs through all of Genesis and into the other four books of the Torah) these two verbs, "create" and "forgive", are reserved exclusively for divine actions.[33]

Intertextuality is the way biblical stories refer to and reflect one another. Such echoes are seldom coincidental—for instance, the word used for ark is the same used for the basket in which Moses is saved, implying a symmetry between the stories of two divinely chosen saviours in a world threatened by water and chaos.[34] The most significant such echo is a reversal of the Genesis creation narrative; the division between the "waters above" and the "waters below" the earth is removed, the dry land is flooded, most life is destroyed, and only Noah and those with him survive to obey God's command to "be fruitful and multiply."[35]

The flood is a reversal and renewal of God's creation of the world.[36] In Genesis 1 God separates the "waters above the earth" from those below so that dry land can appear as a home for living things, but in the flood story the "windows of heaven" and "fountains of the deep" are opened so that the world is returned to the watery chaos of the time before creation.[37] Even the sequence of flood events mimics that of creation, the flood first covering the earth to the highest mountains, then destroying, in order, birds, cattle, beasts, "swarming creatures", and finally mankind.[37] (This parallels the Babylonian flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where at the end of rain "all of mankind had returned to clay," the substance of which they had been made.)[38] The Ark itself is likewise a microcosm of Solomon's Temple.

Later traditions

Jewish

In Jewish folklore, the kind of water that was pouring to the earth for forty days is not common rainfall; rather, God bade each drop pass through Gehenna before it fell to earth, which 'hot rain' scalded the skin of the sinners. The punishment that overtook them was befitting their crime. As their sensual desires had made them hot, and inflamed them to immoral excesses, so they were chastised by means of heated water.[39]

Christianity

The Genesis flood narrative is included in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible (see Books of the Bible). Jesus and the apostles additionally taught on the Genesis flood narrative in New Testament writing (Matthew 24:37–39, Luke 17:26–27, 1 Peter 3:20, 2 Peter 2:5, 2 Peter 3:6, Hebrews 11:7).[40][41] Some Christian biblical scholars suggest that the flood is a picture of salvation in Christ—the Ark was planned by God and there is only one way of salvation through the door of the Ark, akin to one way of salvation through Christ.[42][40] Additionally, some scholars commenting on the teaching of the apostle Peter (1 Peter 3:18–22), connect the Ark with the resurrection of Christ; the waters burying the old world but raising Noah to a new life.[42][40] Christian scholars also highlight that 1 Peter 3:18–22 demonstrates the Genesis flood as a type to Christian baptism.[43][44][40]

Gnosticism

In the 3rd century Gnostic codex now referred to as the Hypostasis of the Archons, it is the corrupt rulers (Archons) who decide to flood the world in order to dispose of most of mankind. However, Noah is spared and told to build an ark. But when his wife Norea wants to board the ark, Noah attempts to not let her, thus she uses her divine power to blow on the ark, causing it to be consumed by fire. Noah later builds the ark a second time. When the Archons try to seize Norea, she calls out to God for help, then the angel Eleleth appears and scares away the Archons, revealing to Norea that she is a divine child of the great spirit. A different view is found in the Secret Book of John; instead of an ark, Noah hides in a bright cloud.[45]

Mandaeism

Mandaeism teaches that the flood of Noah was the last of three events where the world's population was reduced to a single family. Thirty generations after Adam, most of the population was killed by pestilence and war, leaving only Ram and his wife Rud. Twenty-five generations later, most of the population was killed by fire, leaving only Shurbai and his wife Shurhabil. Fifteen generations later, most of the population was killed by flood, leaving only Noah and Shem,[46] in addition to the latter's wife Nuraitha.[47]

Islam

The story of Noah and the Great Flood is related in the Qur'an in the surah Nūḥ.

Historicity

Academic scholars and researchers consider the story in its present form to be exaggerated and/or implausible.[8][48] However, it is notable that the story of the Deluge describes either a severe genetic bottleneck event or the origins of a founder effect among the descendants of the survivors, in that the survivors are related. As yet, there is no evidence of such a severe genetic bottleneck at that period of time (~7000 years before the present day) either among humans or other animal species;[49] however, if the flood narrative is derived from a more localized event and describes a founder effect among one population of humans, certain explanations such as the events described by the Black Sea deluge hypothesis may elaborate on the historicity of the flood narrative.

Evidence does exist for localized catastrophic flooding in the geological record: the Channeled Scablands in the southeastern areas of the state of Washington have been demonstrated to have been formed by a series of catastrophic floods[50][51] originating from the collapse of glacial dams of glacial lakes in the region, the last of which has been estimated to have occurred between 18,200 and 14,000 years ago.[52]

Another geologic feature believed to have been formed by massive catastrophic flooding is the Tsangpo Gorge in Tibet.[53][54] As with the Channeled Scablands of the state of Washington, breakthroughs of glacial ice dams are believed to have unleashed massive and sudden torrents of water to form the gorge some time between 600 and 900 AD.[54]

The current understanding of the prehistoric cataclysmic flooding from the Altai Mountains is that several glacial lake outburst floods from the Altai Mountains caused massive flooding along the Katun River (in the present-day Altai Republic) some time between 12000 BC and 9000 BC,[55][56][57][58] as demonstrated by the fact that much of the gravel deposited along the Katun valley lacks a stratigraphic structure, instead showing characteristics of a deposition directly after suspension in a turbulent flow.[59]

Flood geology

The development of scientific geology had a profound impact on attitudes towards the biblical flood narrative by undermining the biblical chronology, which placed the Creation and the flood no more than a few thousand years back in history. In 1823 the English theologian and natural scientist William Buckland interpreted geological phenomena as Reliquiæ Diluvianæ (relics of the flood) "Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge". His views were supported by others at the time, including the influential geologist Adam Sedgwick, but by 1830 Sedgwick considered that the evidence suggested only local floods. Louis Agassiz subsequently explained such deposits as the results of glaciation.[60][61]

In 1862, William Thomson (later to become Lord Kelvin) calculated the age of the Earth at between 24 million and 400 million years, and for the remainder of the 19th century, discussion focused not on the viability of this theory of deep time, but on the derivation of a more precise figure for the age of the Earth.[62] Lux Mundi, an 1889 volume of theological essays which marks a stage in the acceptance of a more critical approach to scripture, took the stance that readers should rely on the gospels as completely historical, but should not take the earlier chapters of Genesis literally.[63] By a variety of independent means, scientists have determined that the Earth is approximately 4.54 billion years old.[64][65][66][67]

Flood geology (a pseudoscience which contradicts a number of principles and discoveries of fact in the fields of geology, stratigraphy, geophysics, physics, paleontology, biology, anthropology, and archaeology in an attempt to interpret and reconcile geological features on Earth in accordance with a literal understanding of the Genesis flood narrative)[11][68][8][69][70][71][72][73] can be traced to "Scriptural geologists," a heterogeneous group of writers from the early 19th century, most of whom lacked any background in geology and also lacked influence even in religious circles.[74][75] The geologic views of these writers were ignored by the scientific community of their time.[76][77][78]

Flood geology was largely ignored in the 19th century, but was revived in the 20th century by the Seventh-day Adventist George McCready Price,[79] who was inspired by the visions of Ellen G. White. As Price's career progressed, he gained attention outside of Seventh-day Adventist groups, and by 1929 he was a popular scientific author among Christian fundamentalists, though those who were not Seventh-day Adventists rejected his young Earth theories.[80] Through the middle of the 20th century, despite debates between Protestant Christian scientists,[81][82][83] Flood geology maintained traction amongst evangelical Christian circles. Historian Ronald Numbers argues that an ideological connection by evangelical Christians wanting to challenge aspects of the scientific consensus that they believe contradict their interpretation of religious texts was first established by the publication of the 1961 book, The Genesis Flood.[84]

Most scientific fields, particularly those contradicted by flood geology, rely on Charles Lyell's established principle of uniformitarianism, which for much of their history was seen to contrast with the catastrophism inherent in flood geology. However, with the discovery of evidence for some catastrophic events, events similar to those on which the flood narrative may be based are accepted as possible within an overall uniformitarian framework.[85][86] In relation to geological forces, uniformitarianism explains the formation of the Earth's features by means of mostly slow-acting forces seen in operation today.

Species distribution

By the 17th century, believers in the Genesis account faced the issue of reconciling the exploration of the New World and increased awareness of the global distribution of species with the older scenario whereby all life had sprung from a single point of origin on the slopes of Mount Ararat. The obvious answer involved mankind spreading over the continents following the destruction of the Tower of Babel and taking animals along, yet some of the results seemed peculiar. In 1646 Sir Thomas Browne wondered why the natives of North America had taken rattlesnakes with them, but not horses: "How America abounded with Beasts of prey and noxious Animals, yet contained not in that necessary Creature, a Horse, is very strange".[9]

Browne, among the first to question the notion of spontaneous generation, was a medical doctor and amateur scientist making this observation in passing. However, biblical scholars of the time, such as Justus Lipsius (1547–1606) and Athanasius Kircher (c. 1601–1680), had also begun to subject the Ark story to rigorous scrutiny as they attempted to harmonize the biblical account with the growing body of natural historical knowledge. The resulting hypotheses provided an important impetus to the study of the geographical distribution of plants and animals, and indirectly spurred the emergence of biogeography in the 18th century. Natural historians began to draw connections between climates and the animals and plants adapted to them. One influential theory held that the biblical Ararat was striped with varying climatic zones, and as climate changed, the associated animals moved as well, eventually spreading to repopulate the globe.[9]

There was also the problem of an ever-expanding number of known species: for Kircher and earlier natural historians, there was little problem finding room for all known animal species in the Ark. Less than a century later, discoveries of new species made it increasingly difficult to justify a literal interpretation for the Ark story.[87] By the middle of the 18th century only a few natural historians accepted a literal interpretation of the narrative.[69]

See also

- Biblical cosmology

- Chronology of the Bible

- Documentary hypothesis

- Mosaic authorship

- Noach (parsha)

- Panbabylonism

Notes

- ^ The controversial existence of a chiasm is not an argument against the construction of the story from two sources. See the overview in Friedman (1996), p. 91

References

Citations

- ^ Leeming 2010, p. 469.

- ^ Bandstra 2008, p. 61.

- ^ a b Oliver 2017, p. 12.

- ^ a b Gmirkin 2006, p. 3.

- ^ a b Worthington 2019, p. 147.

- ^ a b Cline 2007, p. 20.

- ^ a b Arnold 2009, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Montgomery 2012.

- ^ a b c Cohn 1999.

- ^

- Kuchment, Anna (August 2012). "The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Scientific American. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Raff, Rudolf A. (20 January 2013). "Genesis meets geology. A review of the rocks don't lie; a geologist investigates Noah's flood, by David R. Montgomery". Evolution & Development. 15 (1): 83–84. doi:10.1111/ede.12017.

- "The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Publishers Weekly. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Bork, Kennard B. (December 2013). "David R. Montgomery. The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood". Isis. 104 (4): 828–829. doi:10.1086/676345.

- McConnachie, James (31 August 2013). "The Rocks Don't Lie, by David R. Montgomery - review". The Spectator. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Prothero, Donald R. (2 January 2013). "A Gentle Journey Through the Truth in Rocks". Skeptic. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ a b Isaak 2007, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Walton & Longman III 2018, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Cohn 1999, p. 11–12.

- ^ Kaltner & McKenzie 2014, p. 74.

- ^ Berman 2017, pp. 236–268.

- ^ Gary A. Rendsburg, The biblical flood story in the light of the Gilgameš flood account, p.116

- ^ Bridge 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Habel 1988, p. 23.

- ^ Chen 2013, p. 1,11.

- ^ Finkel 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Dalley 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Collins 2017, p. 10–11.

- ^ Burton 2019, p. 1978-79.

- ^ a b c d Guillaume 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Miano 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Guillaume 2010, p. 73-74.

- ^ Guillaume 2010, p. 73–74.

- ^ VanderKam 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Gilbert, Christopher (2009). A Complete Introduction to the Bible. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809145522.

- ^ Darshan, Guy (2016). "The Calendrical Framework of the Priestly Flood Story in Light of a New Akkadian Text from Ugarit (RS 94.2953)". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (3): 507–514. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0507. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0507.

- ^ Schule 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Schule 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Schule 2017, p. 3-4.

- ^ Bodner 2016, pp. 95–96: "There is increasing recognition that the pentateuchal narrative is seldom careless or arbitrary," write John Bergsma and Scott Hahn, "and intertextual echoes are seldom coincidental."17

- ^ Levenson 1988, p. 10–11.

- ^ Baden 2012, p. 184.

- ^ a b Keiser 2013, p. 133.

- ^ Keiser 2013, p. 133 fn.29.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I : The Inmates of the Ark (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ a b c d "Flood, the – Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology Online". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Creation Worldview Ministries: The New Testament and the Genesis Flood: A Hermeneutical Investigation of the Historicity, Scope, and Theological Purpose of the Noahic Deluge". www.creationworldview.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b Wiersbe, Warren (1993). Wiersbe's expository outlines on the Old Testament. Wheaton, Illinois: Victor Books. ISBN 978-0896938472. OCLC 27034975.

- ^ Matthew, Henry (2000). Matthew henry's concise commentary on the whole bible. Nelson's concise series. [Place of publication not identified]: Nelson Reference & Electronic. ISBN 978-0785245292. OCLC 947797222.

- ^ "The Typological Interpretation of the Old Testament, by G.R. Schmeling". www.bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ Marvin Meyer; Willis Barnstone (2009). "The Reality of the Rulers (The Hypostasis of the Archons) and The Secret Book of John". The Gnostic Bible. Shambhala. ISBN 9781590306314. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Book Two, 1st Glorification: Upon Each Faithful Mandaean, I Will Place My Right Hand". Ginza Rabba. Vol. Right Volume. Translated by Al-Saadi, Qais; Al-Saadi, Hamed (2nd ed.). Germany: Drabsha. 2019. pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Book Nineteen: The Deluge". Ginza Rabba. Vol. Right Volume. Translated by Al-Saadi, Qais; Al-Saadi, Hamed (2nd ed.). Germany: Drabsha. 2019. pp. 203–204. [Note: this book, or a larger text containing it, is numbered book 18 in some other editions.]

- ^ Weber, Christopher Gregory (1980). "The Fatal Flaws of Flood Geology". Creation Evolution Journal. 1 (1): 24–37.

- ^ Naturalis Historia blog. "The Great Genetic Bottleneck that Contradicts Ken Ham’s Radical Accelerated Diversification (Post-Flood Hyper-Evolution)." https://thenaturalhistorian.com/2016/03/30/the-great-genetic-bottleneck-that-contradicts-ken-hams-radical-accelerated-diversification-ie-post-flood-hyper-evolution/

- ^ Bjornstad, B.; Kiver, E. (2012). On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods: The Northern Reaches: A geological field guide to northern Idaho and the Channeled Scabland. Sandpoint, Idaho: Keokee Books. ISBN 978-1879628397.

- ^ Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A. Jackson, eds. (2005) Glossary of Geology (5th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia, American Geological Institute. 779 pp. ISBN 0-922152-76-4

- ^ Balbas, A.M., Barth, A.M., Clark, P.U., Clark, J., Caffee, M., O'Connor, J., Baker, V.R., Konrad, K. and Bjornstad, B., 2017. 10Be dating of late Pleistocene megafloods and Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreat in the northwestern United States. Geology, 45(7), pp. 583-586.

- ^ Montgomery DR."Biblical-Type Floods Are Real, and They're Absolutely Enormous." Discover Magazine, 2012 August 29. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/biblical-type-floods-are-real-and-theyre-absolutely-enormous

- ^ a b University of Washington. "Historic Himalayan Ice Dams Created Huge Lakes, Mammoth Floods." Science News, 2004 December 27. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/12/041220010147.htm

- ^ "Rudoy, A.N., Baker, V. R. Sedimentary effects of cataclysmic late Pleistocene glacial outburst flooding, Altay Mountains, Siberia // Sedimentary Geology, 85 (1993) 53-62". Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Baker, V. R., G. Benito, A. N. Rudoy, Paleohydrology of late Pleistocene Superflooding, Altay Mountains, Siberia, Science, 1993, Vol. 259, pp. 348-352

- ^ Rudoy A.N. Mountain Ice-Dammed Lakes of Southern Siberia and their Influence on the Development and Regime of the Runoff Systems of North Asia in the Late Pleistocene. Chapter 16. (P. 215—234.) — Palaeohydrology and Environmental Change / Eds: G. Benito, V.R. Baker, K.J. Gregory. — Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1998. 353 p.

- ^ Grosswald, M.G., 1998, New approach to the ice age paleohydrology of northern Eurasia. Chapter 15. (P. 199-214)— Palaeohydrology and Environmental Change / Eds: G. Benito, V.R. Baker, K.J. Gregory. — Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1998. 353 p.

- ^ "Rudoy, A.N., Baker, V. R. Sedimentary effects of cataclysmic late Pleistocene glacial outburst flooding, Altay Mountains, Siberia // Sedimentary Geology, 85 (1993) 53-62". Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Herbert, Sandra (1991). "Charles Darwin as a prospective geological author". British Journal for the History of Science. No. 24. pp. 171–174. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Buckland, W. (1823). Reliquiæ Diluvianæ: Or Observations on the Organic Remains Contained in Caves, Fissures, and Diluvial Gravel, and on Other Geological Phenomena, Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge. J. Murray. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Dalrymple 1991, pp. 14–17

- ^ Barr, James (4 March 1987). Biblical Chronology, Fact or Fiction? (PDF). University of London. p. 17. ISBN 978-0718708641. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ "Age of the Earth". U.S. Geological Survey. 1997. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 10 January 2006.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094.

- ^ Manhesa, Gérard; Allègre, Claude J.; Dupréa, Bernard & Hamelin, Bruno (1980). "Lead isotope study of basic-ultrabasic layered complexes: Speculations about the age of the earth and primitive mantle characteristics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 47 (3): 370–382. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..47..370M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2.

- ^ Braterman, Paul S. (2013). "How Science Figured Out the Age of Earth". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016.

- ^ Senter, Phil. "The Defeat of Flood Geology by Flood Geology." Reports of the National Center for Science Education 31:3 (May–June 2011). Printed electronically by California State University, Northridge. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b Young 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Isaak 2006, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Morton 2001, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Isaak 2007, p. 173.

- ^ Stewart 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Piccardi, L.; Masse, W. Bruce (2007). Myth and Geology. London: Geological Society. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-86239-216-8.

- ^ Livingstone, David; Hart, Darryl G.; Noll, Mark A. (1999). Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511557-4.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1988). The Great Devonian Controversy. Springer. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-0-226-73102-5.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin J. S. (2008). Worlds before Adam. University of Chicago Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-226-73128-5.

- ^ Wood, Paul (2004). Science and Dissent in England, 1688–1945. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3718-9.

- ^ Young, Davis A.; Stearley, Ralph F. (2008). The Bible, rocks, and time : geological evidence for the age of the earth. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-2876-0.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. (1993). The Creationists. University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-520-08393-6.

- ^ Kulp, J. Laurence (1950). "Deluge Geology". Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. 2 (1): 1–15. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ^ Yang, Seung-Hun (1993). "Radiocarbon Dating and American Evangelical Christians". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. (1993). The Creationists. University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-520-08393-6.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. (2006). The creationists : from scientific creationism to intelligent design (Expanded, First Harvard University Press paperback ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-674-02339-0. OCLC 69734583.

- ^ Allen, E. A., et al., 1986, Cataclysms on the Columbia, Timber Press, Portland, OR.ISBN 978-0-88192-067-3

- "Bretz knew that the very idea of catastrophic flooding would threaten and anger the geological community. And here's why: among geologists in the 1920s, catastrophic explanations for geological events (other than volcanos or earthquakes) were considered wrong-minded to the point of heresy." p. 42.

- "Consider, then, what Bretz was up against. The very word 'Catastrophism' was heinous in the ears of geologists. ... It was a step backward, a betrayal of all that geological science had fought to gain. It was a heresy of the worst order." p. 44

- "It was inevitable that sooner or later the geological community would rise up and attempt to defeat Bretz's 'outrageous hypothesis.'" p 49

- "Nearly 50 years had passed since Bretz first proposed the idea of catastrophic flooding, and now in 1971 his arguments had become a standard of geological thinking." p. 71

- ^ Ager, Derek V. (1993). The Nature of the Stratigraphical Record (3rd ed.). Chichester, New York, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-471-93808-4.

- "geologists do not deny uniformitarianism in its true sense, that is to say, of interpreting the past by means of the processes that are seen going on at the present day, so long as we remember that the periodic catastrophe is one of those processes. Those periodic catastrophes make more showing in the stratigraphical record than we have hitherto assumed."

- ^ Browne 1983, p. 276.

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert (2008). The Five Books of Moses. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393070248.

- Arnold, Bill T. (2009). Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521000673.

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300152647.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament : an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0495391050.

- Barr, James (28 March 2013). Bible and Interpretation: The Collected Essays of James Barr. Volume II: Biblical Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-19-969289-7.

- Berman, Joshua A. (2017). Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-065882-3.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A discursive commentary on Genesis 1-11. Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567372871.

- Bridge, Steven L. (2009). Getting the Old Testament. Baker. ISBN 9781441232779.

- Burton, Keith A. (2019). Symbolic numbers. Eerdmans. ISBN 9781467460460.

- Carr, David M. (2021). Genesis 1-11. Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Bodner, Keith (2016). An Ark on the Nile: The Beginning of the Book of Exodus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-878407-4.

- Browne, Janet (1983), The Secular Ark: Studies in the History of Biogeography, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 276, ISBN 0-300-02460-6

- Chen, Y. S. (2013). The Primeval Flood Catastrophe: Origins and Early Development in Mesopotamian Traditions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199676200.

- Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile. National Geographic. ISBN 9781426212246.

- Cohn, Norman (1999). Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300076486.

- Guillaume, Philippe (2010). Land and Calendar. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567401205.

- Collins, Matthew A. (2017). "An Ongoing Tradition". In Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda; Morgan, Jon (eds.). Noah as Antihero. Routledge. ISBN 9781351720700.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2008). Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-102721-5.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (1991), The Age of the Earth, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2331-1

- Finkel, Irving (2014). The Ark Before Noah. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781444757071.

- Friedman, Richard E. (1996). "Non-Arguments Concerning the Documentary Hypothesis". In Fox, Michael V.; Hurowitz, V. A. (eds.). Texts, Temples and Traditions. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060033.

- Gmirkin, Russell E. (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Isaak, M (1998). "Problems with a Global Flood". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- Isaak, Mark (5 November 2006). "Index to Creationist Claims, Geology". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Isaak, Mark (2007). The Counter-Creationism Handbook. University of California Press.

- Kaltner, John; McKenzie, Steven (2014). The Old Testament: Its Background, Growth, and Content. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Keiser, Thomas A. (2013). Genesis 1-11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological Message. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781625640925.

- Leeming, David A. (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841749.

- Levenson, Jon Douglas (1988). Creation and the persistence of evil : the Jewish drama of divine omnipotence. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780062548450. OCLC 568745811.

- Montgomery, David R. (2012). The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood. Norton. ISBN 9780393082395.

- Miano, David (2010). Shadow on the Steps. Society for Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589834781.

- Morton, Glenn (17 February 2001). "The Geologic Column and its Implications for the Flood". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Oliver, Simon (2017). Creation. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567656117.

- Sailhamer, John H. (2010). The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830878888.

- Schule, Andreas (2017). Theology from the Beginning. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161539978.

- Stewart, Melville Y. (2010). Science and religion in dialogue. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4051-8921-7.

- Young, Davis A. (1995). "Diluvial Cosmogonies and the Beginnings of Geology". The Biblical Flood: A Case Study of the Church's Response to Extrabiblical Evidence. Eerdmans. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-8028-0719-9. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007.

- Young, Davis A.; Stearley, Ralph F. (18 August 2008). The Bible, Rocks and Time: Geological Evidence for the Age of the Earth. InterVarsity Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8308-2876-0.

- VanderKam, James C. (2002). Calendars in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Routledge. ISBN 9781134709632.

- Walton, John H.; Longman III, Tremper (2018). The Lost World of the Flood: Mythology, Theology, and the Deluge Debate. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-8782-8.

- Worthington, Martin (2019). Ea's Duplicity in the Gilgamesh Flood Story. Routledge. ISBN 9780830878888.

Further reading

- Cotter, David W. (2003). Genesis. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814650400.

- Habel, Norman C. (1988). "Two Flood Myths". In Dundes, Alan (ed.). The Flood Myth. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520063532.

- Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The book of Genesis: chapters 1–17. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825216.

- Kessler, Martin; Deurloo, Karel Adriaan (2004). A commentary on Genesis: the book of beginnings. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809142057.

- Knecht, Friedrich Justus (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: introduction and annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195297515.

- McKeown, James (2008). Genesis. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827050.

- Middleton, J. Richard (2005). The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1. Brazos Press. ISBN 9781441242785.

- Rogerson, John William (1991). Genesis 1–11. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567083388.

- Sacks, Robert D (1990). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Edwin Mellen.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). "Genesis". In James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Whybray, R.N (2001). "Genesis". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

No comments:

Post a Comment