- Full Index to All Things Tolkien incld Rings of Power

- Tolkien - The History and Ages of Arda

- Cosmology of Tolkien's Legendarium

- Tolkien - The Ainur and Maiar of Middle-earth

- Tolkien - The Elves of Middle-earth and Valar of Vala

- The Inspiration of William Morris upon JRR Tolkien's Middle-Earth

- Tolkien's Tropes and Listings

- Tolkien - LOTR: The Rings of Power

- Middle-Earth: The Fall of Gondolin

- Middle-Earth: Beren and Luthien

- Middle-Earth: The Age of Numenor

- Middle-Earth: It's History, Unfinished Tales, Tom Bombadil, & the Lands of Beleriand

- Middle-Earth: The Many Worlds of the Silmarillion

- Middle-Earth: Sorting Out Tolkien's Many Titles & Works

- Middle-Earth: Lore, Legends, Symbols & Maps

- Middle-Earth: JRR Tolkien's Biography

- Middle-Earth: JRR Tolkien's Titles

The History of Middle-earth

The front cover of Volume 9 | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin (UK) |

Publication date | 1983 to 1996 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 12 volumes |

| Preceded by | The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays |

| Followed by | Roverandom |

The History of Middle-earth is a 12-volume series of books published between 1983 and 1996 that collect and analyse much of Tolkien's legendarium, compiled and edited by his son, Christopher Tolkien. The series shows the development over time of Tolkien's conception of Middle-earth as a fictional place with its own peoples, languages, and history, from his earliest notions of a "mythology for England" through to the development of the stories that make up The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings. It is not a "history of Middle-earth" in the sense of being a chronicle of events in Middle-earth written from an in-universe perspective; it is instead an out-of-universe history of Tolkien's creative process. In 2000, the twelve volumes were republished in three limited edition omnibus volumes. Non-deluxe editions of the three volumes were published in 2002.[1]

Contents

Some of the content consists of earlier versions of already published works, while other portions are new material. These books are extremely detailed, often analysing a scrap of paper to provide the full evolution of two or even three different versions of a passage that were rewritten over each other. Despite the great amount of material in the twelve volumes, numerous unpublished texts are still known to exist in the Bodleian and Marquette University libraries, and in other papers held by individuals or organizations, such as the Elvish Linguistic Fellowship.

The first five books track the early history of The Silmarillion and related texts. Books six to nine discuss the development of The Lord of the Rings; book nine also discusses the Númenor story in the form of The Notion Club Papers. Books ten and eleven focus on material from the Silmarillion that Tolkien worked on after The Lord of the Rings was published, including the Annals of Beleriand and the Annals of Aman. Book twelve discusses the development of the Appendices to The Lord of the Rings and examines assorted writings from the last years of Tolkien's life.

Christopher Tolkien made the decision not to include any material related to The Hobbit in The History of Middle-earth because it was not originally intended to form part of the mythology, but was a children's story and originally not set in Middle-earth, revised during the writing of The Lord of the Rings. The History of The Hobbit was published separately, in two volumes, in 2007 and was edited by John D. Rateliff.

Volumes

|

|

|

|

A combined index was published six years after the series was completed as The History of Middle-earth: Index (2002).

A shorter version of volume 9, omitting material not related to The Lord of the Rings, was published as The End of the Third Age; this is usually sold as a boxed set along with volumes 6, 7 and 8 as The History of the Lord of the Rings.

References

- ^ "The History of Middle-earth". An Illustrated Tolkien Bibliography. TolkienBooks.net. 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

Further reading

- Bratman, David (2000). "The Literary Value of 'The History of Middle-earth'". Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy (86): 69–94.

- Whittingham, Elizabeth A. (2017). The Evolution of Tolkien's Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1174-7.

External links

Unfinished Tales

Cover of the first edition. It features Tolkien's drawing of a Númenórean helmet. | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Illustrator | Christopher Tolkien (maps) |

| Cover artist | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin |

Publication date | 1980 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| ISBN | 9780048231796 |

| Preceded by | The Silmarillion |

| Followed by | The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien |

Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth is a collection of stories and essays by J. R. R. Tolkien that were never completed during his lifetime, but were edited by his son Christopher Tolkien and published in 1980. Many of the tales within are retold in The Silmarillion, albeit in modified forms; the work also contains a summary of the events of The Lord of the Rings told from a less personal perspective.

Overview

Unlike The Silmarillion, also published posthumously (in 1977), for which the narrative fragments were modified to connect into a consistent and coherent work, the Unfinished Tales are presented as Tolkien left them, with little more than names changed (the author having had a confusing habit of trying out different names for a character while writing a draft). Thus some of these are incomplete stories, while others are collections of information about Middle-earth. Each tale is followed by a long series of notes explaining inconsistencies and obscure points.

As with The Silmarillion, Christopher Tolkien edited and published Unfinished Tales before he had finished his study of the materials in his father's archive. Unfinished Tales provides more detailed information about characters, events and places mentioned only briefly in The Lord of the Rings. Versions of such tales, including the origins of Gandalf and the other Istari (Wizards), the death of Isildur and the loss of the One Ring in the Gladden Fields, and the founding of the kingdom of Rohan, help expand knowledge about Middle-earth.

The commercial success of Unfinished Tales demonstrated that the demand for Tolkien's stories several years after his death was not only still present but growing. Encouraged by the result, Christopher Tolkien embarked upon the more ambitious twelve-volume work entitled The History of Middle-earth which encompasses nearly the entire corpus of his father's writings about Middle-earth.

Contents

Part One: The First Age

- "Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin"

- "Narn i Hîn Húrin (The Tale of the Children of Húrin)"

Part Two: The Second Age

- "A Description of the Island of Númenor"

- "Aldarion and Erendis: The Mariner's Wife"

- "The Line of Elros: Kings of Númenor"

- "The History of Galadriel and Celeborn"

Part Three: The Third Age

- "The Disaster of the Gladden Fields"

- "Cirion and Eorl and the Friendship of Gondor and Rohan"

- "The Quest of Erebor"

- "The Hunt for the Ring"

- "The Battles of the Fords of Isen"

Part Four

- "The Drúedain"

- "The Istari"

- "The Palantíri"

Reception

The scholar Paul H. Kocher, reviewing Unfinished Tales in Mythlore, notes that all the stories are linked to either The Silmarillion, Akallabeth or The Lord of the Rings, and extensively annotated, mainly by Christopher Tolkien. In Kocher's view, the stories contain "some of Tolkien's best writing" (and he summarizes them in some detail), though there is much of interest in the editorial material also. He notes the revised map with the additional placenames used in the tales, and that the book does not address Tolkien's poetry.[1]

The independent scholar Douglas C. Kane writes that Christopher Tolkien chose to include not just narrative tales, despite the book's title, but "a taste of some of the descriptive and historical underpinnings of those heretofore uncharted vistas", and that indeed he suggested he might "dive even deeper into the history of his father's legendarium", as he eventually did with his 12-volume The History of Middle-earth.[2] The Tolkien scholar Corey Olsen notes that Christopher Tolkien chose to present the incomplete tales as they were, adding a commentary to help readers grasp how they fitted in to his father's Middle-earth legendarium. Olson comments that the book's commercial success demonstrated the existence of a market for more of Tolkien's writings, opening up a route to publication of the 12-volume The History of Middle-earth.[3]

The Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft wrote in Christianity & Literature that many readers had felt disappointed by Unfinished Tales, as some had felt about The Silmarillion.[4] Perry Bramlett adds that the book is not for the reader new to Tolkien, nor even one who has read only The Hobbit "or perhaps some or even all of the Lord of the Rings." He notes Christopher Tolkien's warning that the stories "constitute no whole" and that much of the content "will be found unrewarding" to those without a good knowledge of Lord of the Rings. More positively, he cites David Bratman's comment[5] that much of it is as well-crafted as any of Tolkien's writings, and that readers who found The Silmarillion "a little too high and distant" would welcome it.[6]

The science fiction author Warren Dunn, writing in 1993, described the book as engaging, and that every section contained "something of interest", but he cautioned that it required "an intimate knowledge" of The Silmarillion, The Lord of the Rings, and its appendices "for full enjoyment" of the book. He commented that "I really do wish we could have seen the whole history like this, even if it took up twelve volumes to get through the first, second and third ages before the Lord of the Rings!"[7]

References

- ^ Kocher, Paul H. (1981). "Reviews: Unfinished Tales". Mythlore. 7 (4): 31–33.

- ^ Kane, Douglas C. (2021). "The Nature of Middle-earth (2021) by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Carl F. Hostetter". Journal of Tolkien Research. 13 (1). Article 5.

- ^ Olsen, Corey (2014). "Unfinished Tales". Mythgard Institute. Signum University. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Kreeft, Peter (1982). "Book Review: The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien". Christianity & Literature. 31 (4): 107–109. doi:10.1177/014833318203100434. ISSN 0148-3331.

- ^ Bratman, David (November 1980). "Unfinished Tales - Review". Mythprint. 17 (6): 1.

- ^ Bramlett, Perry C. (2003). I Am in Fact a Hobbit: An Introduction to the Life and Works of J. R. R. Tolkien. Mercer University Press. pp. 153–159. ISBN 978-0-86554-894-7.

- ^ Dunn, Warren (26 February 1993). "Unfinished Tales". Ossus Library. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

| |

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Pauline Baynes |

| Cover artist | Pauline Baynes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Fantasy |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin |

Publication date | 1962[1] |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 304 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-0007557271 |

| Preceded by | The Lord of the Rings |

| Followed by | Tree and Leaf |

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil is a 1962 collection of poetry by J. R. R. Tolkien. The book contains 16 poems, two of which feature Tom Bombadil, a character encountered by Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings. The rest of the poems are an assortment of bestiary verse and fairy tale rhyme. Three of the poems appear in The Lord of the Rings as well. The book is part of Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium.[2]

The volume includes The Sea-Bell, subtitled Frodos Dreme, which W. H. Auden considered Tolkien's best poem. It is a piece of metrical and rhythmical complexity that recounts a journey to a strange land beyond the sea. Drawing on medieval 'dream vision' poetry and Irish immram poems, the piece is markedly melancholic and the final note is one of alienation and disillusion.[3]

The book was originally illustrated by Pauline Baynes and later by Roger Garland. The book, like the first edition of The Fellowship of the Ring, is presented as if it is an actual translation from the Red Book of Westmarch, and contains some background information on the world of Middle-earth that is not found elsewhere: e.g. the name of the tower at Dol Amroth and the names of the Seven Rivers of Gondor. There is some fictional background information about those poems, linking them to Hobbit folklore and literature and to their supposed writers, in some cases Sam Gamgee.

The book uses the letter "K" instead of "C" for the /k/ sound in Sindarin (one of the languages invented by Tolkien), a spelling variant Tolkien used many times in his writings.

Contents

The poems are all supposedly works that Hobbits enjoyed; all are in English. Several are attributed in a mock-scholarly preface to Hobbit authors or traditions. Three are also among the many poems in The Lord of the Rings.[4][5]

| Group[4] | No. | Title | Date | Hobbit "Author" | Lord of the Rings ch. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tom Bombadil | 1 | The Adventures of Tom Bombadil | 1934 | Buckland tradition | The character was named for a Dutch doll owned by Tolkien's children.[6] | |

| Tom Bombadil | 2 | Bombadil Goes Boating | 1962 | Buckland tradition | written for the book | |

| Fairies | 3 | Errantry | 1933 | Bilbo Baggins | Shares rhyming scheme, metre and some lines with "Song of Eärendil" | |

| Fairies | 4 | Princess Mee | 1924 | Originally called "The Princess Ni" | ||

| Man in the Moon | 5 | The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late | 1923 | Bilbo Baggins | I.9 "At the Sign of the Prancing Pony" | Sung by Frodo in Bree expanded from "Hey Diddle Diddle (the Cat and the Fiddle)" |

| Man in the Moon | 6 | The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon | 1915 (MS) | "ultimately from Gondor" | Mentions Bay of Belfalas | |

| Trolls | 7 | The Stone Troll | 1954 | Sam Gamgee | I.12 "Flight to the Ford" | Recited by Sam in the Trollshaws |

| Trolls | 8 | Perry-the-Winkle | Sam Gamgee | |||

| An odd one out | 9 | The Mewlips | 1937 | Originally called "Knocking at the Door". It concerns the Mewlips, an imaginary race of evil creatures that feed on passers by, collecting their bones in a sack. The poem describes the long and lonely road needed to reach the Mewlips, travelling beyond the Merlock Mountains, and through the marsh of Tode and the wood of "hanging trees and gallows-weed". None of these names appear on maps of Middle-earth. "Gorcrow" is an old name for the carrion crow. | ||

| Bestiary | 10 | Oliphaunt | 1927 | Sam Gamgee | IV.3 "The Black Gate is Closed" | recited in Ithilien |

| Bestiary | 11 | Fastitocalon | 1927 | Originally called "Adventures in Unnatural History and Medieval Metres, being the Freaks of Fisiologus" | ||

| Bestiary | 12 | Cat | Sam Gamgee | |||

| Atmosphere and emotion | 13 | Shadow-Bride | 1936 | Originally called "The Shadow Man" | ||

| Atmosphere and emotion | 14 | The Hoard | 1923 | Originally called "Iúmonna Gold Galdre Bewunden" | ||

| Atmosphere and emotion | 15 | The Sea-Bell or "Frodos Dreme" | 1934 | Associated with Frodo Baggins | Originally called "Looney" | |

| Atmosphere and emotion | 16 | The Last Ship | 1934 | "ultimately from Gondor" | Originally called "Firiel" |

Publication history

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil was first published as a stand-alone book in 1962. Some editions, such as the Unwin Paperbacks edition (1975) and Poems and Stories, erroneously state that it was first published in '1961'. Tolkien's letters confirm that 1962 is the correct year.[7] Beginning with The Tolkien Reader in 1966, it was included in anthologies of Tolkien's shorter works. This trend continued after his death with Poems and Stories (1980) and Tales from the Perilous Realm (1997). In 2014 Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond edited a new stand-alone edition, which includes for each poem detailed commentary, original versions and their sources.

Only one of the poems, "Bombadil Goes Boating", was written specially for the book.[8]

Seven of the works in the book are included on the 1967 album of Tolkien's songs and poems, Poems and Songs of Middle Earth. Six are read by Tolkien; the seventh, "Errantry", is set to music by Donald Swann.[9]

Reception

A 1963 Kirkus Reviews described the book's verses as "roll[ing] along in strange meters and weird words". It called the poems "difficult fun to read aloud", but suggested that the Stone Troll and Bombadil himself, though "memorable acquaintances", might be enjoyed more by adults than by children.[10]

Richard C. West wrote that the book was the idea of Tolkien's aunt, Jane Neave, who wanted something about Tom Bombadil, resembling one of Beatrix Potter's Little Books; but that his publishers wanted a larger volume. Accordingly he assembled what he had, on the theme of poems that Hobbits might enjoy, grouping them as the editors Scull and Hammond (in the 2015 edition) say "like with like as far as possible", complete with "mock-scholarly preface".[4]

See also

References

- ^ Scull, Christina & Hammond, Wayne G. (2006), The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide, HarperCollins, 'Chronology' volume, p.601; ISBN 978-0-618-39113-4

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2006). "Poems by Tolkien: The Adventures of Tom Bombadil". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Taylor & Francis. pp. 515–517. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- ^ Roche, Norma (1991). "Sailing West: Tolkien, the Saint Brendan Story, and the Idea of Paradise in the West". Mythlore. 17 (4): 16–20, 62.

- ^ a b c West, Richard C. (2015). "The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book by J.R.R. Tolkien". Tolkien Studies. 12 (1): 173–177. doi:10.1353/tks.2015.0015. ISSN 1547-3163. S2CID 170897746.

- ^ Hargrove, Gene (2006). "Adventures of Tom Bombadil". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-135-88033-0.

- ^ Beal, Jane (2018). "Who is Tom Bombadil?: Interpreting the Light in Frodo Baggins and Tom Bombadil's Role in the Healing of Traumatic Memory in J.R.R. Tolkien's 'Lord of the Rings'". Journal of Tolkien Research. article 1. 6 (1).

Tolkien's inspiration for this character was a brightly-dressed, peg-wood, Dutch doll (with a feather in his hat!) that belonged to his second son, Michael.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1981, ed.), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, George Allen & Unwin, #240 (1 August 1962) & #242 (28 November 1962); ISBN 0-04-826005-3

- ^ "The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and other poetry". The Tolkien Estate. 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Jones, Josh (10 September 2012). "Listen to J.R.R. Tolkien Read Poems from The Fellowship of the Ring, in Elvish and English (1952)". Open Culture. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "The Adventures of Tom Bombadil". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

Further reading

- "Tolkien's Lore: The Songs of Middle-earth" by Diane Marchesani, Mythlore, Vol. 7 : No. 1, Article 1. (1980)

- "Niggle's Leaves: The Red Book of Westmarch and Related Minor Poetry of J.R.R. Tolkien" by Steven M. Deyo, Mythlore, Vol. 12 : No. 3 , Article 8. (1986)

External links

Beleriand

| Beleriand | |

|---|---|

| J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium location | |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | large region |

| Locations | Arvernien, Doriath, Falas, Nargothrond, Nevrast, Ossiriand, Taur-im-Duinath |

| Position | north-west Middle-earth |

| Period | Start of Years of the Trees to end of First Age |

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional legendarium, Beleriand was a region in northwestern Middle-earth during the First Age. Events in Beleriand are described chiefly in his work The Silmarillion, which tells the story of the early ages of Middle-earth in a style similar to the epic hero tales of Nordic literature.[1] Beleriand also appears in the works The Book of Lost Tales,[2] The Children of Húrin,[3] and in the epic poems of The Lays of Beleriand.

Fictional history

At the end of the First Age of Middle-earth, Beleriand was broken in the War of Wrath by the angelic beings, the Maiar, against the demonic Morgoth (a Vala fallen into evil). As the inhabitants of Beleriand, including masterless Orcs, beasts of Angband, Elves, Men and Dwarves, fled, much of Beleriand sank in the sea. Only a small section of East Beleriand remained, and was known thereafter as Lindon, in the Northwest of Middle-earth of the Second and Third Age. Other parts of East Beleriand survived into the Second Age, but were completely destroyed along with the island kingdom of Númenor.[4] Fulfilling a prophecy, the graves of Túrin Turambar and Morwen survived as the island Tol Morwen.[T 1] Likewise, a part of Dorthonion became Tol Fuin, and Himring became an island.

Fictional geography

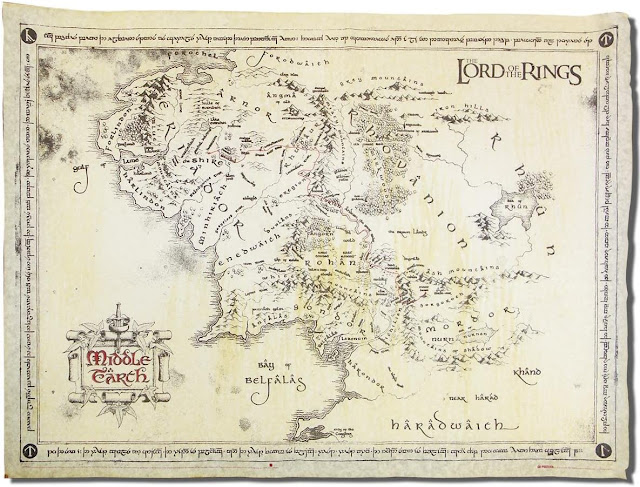

|

| Sketch map of Beleriand. The Ered Luin on the right of the map are on extreme left of the map of Middle-earth, marking the part of Beleriand not destroyed at the end of the First Age. |

The River Sirion, the chief river of Beleriand, running north to south, divided it into West and East Beleriand. Crossing it east to west was a series of hills and a sudden drop in elevation known as Andram, the Long Wall. The river sank into the ground at the Fens of Sirion, and re-emerged below the Andram at the Gates of Sirion. To the east of the Long Wall, was the River Gelion and its six tributaries draining the Ered Luin, in an area known as Ossiriand, "Land of Seven Rivers".

In volume IV of the History of Middle-earth are the early maps of Beleriand, then still called Broseliand, showing the elevation of the land by use of contour lines.[T 2]

In the northwest of Beleriand was a region called Lammoth, "the Great Echo". The Silmarillion explains it is so named because it is where Morgoth and Ungoliant fled after the darkening of Valinor and Morgoth's theft of the Silmarils. Ungoliant lusted for the Silmarils and attacked Morgoth to get them; he let out a great cry, heard across the land.[T 3] In Unfinished Tales, the name instead refers to the acoustic properties of the location and the natural reverberations they cause.[T 4]

Arvernien

Arvernien is the southernmost region of Beleriand, bordered on the east by the Mouths of Sirion.[T 5]

The Mouths were the refuge of the remnants of Eldar and Edain of Beleriand after the Nírnaeth Arnoediad and the Sack of Menegroth. The first rulers of this region were Tuor of the Edain and Idril of Gondolin. Their son Eärendil Half-elven, married the Half-elven Elwing, Dior's daughter. Eärendil and Elwing's sons, Elros and Elrond, were born in Arvernien.

Doriath

Doriath is the realm of the Sindar, the Grey Elves of King Thingol in Beleriand.[T 6] Among the First Age events that occurred in Doriath is the tale of Beren and Lúthien from The Lays of Beleriand, parts of The Children of Húrin and The Silmarillion.

Falas

The Falas was the realm of Círdan the Shipwright and his Sindarin Elves in the years of Starlight and the First Age of Sun. They lived in two havens, Eglarest at the mouth of the River Nenning, and Brithombar at the mouth of the River Brithon. The Havens were besieged during the First Battle of Beleriand. When the Havens were later destroyed, Círdan's people fled to the Mouths of Sirion and the Isle of Balar.

Gondolin

Gondolin was a secret city of Elves in the north of Beleriand, built by Turgon and his Elves, and hidden from the Dark Lord Morgoth by mountains.[T 7] Its destruction is told in The Fall of Gondolin.

Hithlum

Hithlum is the region north of Beleriand near the icy Helcaraxë. It was separated from Beleriand proper by the Ered Wethrin mountain chain, and was named after the sea mists which formed there at times: Hithlum means "Mist-shadow". Hithlum was subdivided into Mithrim, where the High Kings of the Noldor had their halls, and Dor-lómin, later a fief of the House of Hador. Hithlum was cold and rainy, but quite fertile.

March of Maedhros

When the Sons of Fëanor went east after Thingol became aware of the Kinslaying, a great fortress was built on the hill of Himring in northeast Beleriand. It was the chief stronghold of Maedhros, from which he guarded the northeastern border region that became known as the March of Maedhros.[T 8] To the east was Maglor's Gap and Ered Luin; to the west the Pass of Aglon, which Curufin and Celegorm guarded. It was the only fortress to survive the Dagor Bragollach. But in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears the Hill of Himring was taken over by the soldiers of Angband.[T 9] After the Drowning of Beleriand during the War of Wrath, the peak of Himring (also called "Himling", a typographic error) remained above the waves as an island.[T 10]

Nargothrond[

Nargothrond ("The great underground fortress on the river Narog") was the stronghold built by Finrod Felagund, delved into the banks of the river Narog in Beleriand. It was a hidden place from the forces of Morgoth, Finrod established it in the early years of the First Age.

Finrod ruled Nargothrond until he joined Beren in his quest for the Silmaril, and the regency passed to Orodreth. Later, Túrin Turambar came to Nargothrond, persuading the people to fight openly against Morgoth, leading to its sack by the army of the dragon Glaurung. Glaurung used Nargothrond as his lair; he was killed by Túrin, after which the caves were claimed by the Petty-dwarf Mîm, until he was killed by Húrin, Túrin's father.

Nevrast

Nevrast ("Hither Shore", as opposed to Aman) is a coastal region in the north of Beleriand; its city was Vinyamar. It was the centre of Turgon's Elven kingdom until people left for Gondolin. The land was then abandoned until Tuor came there, guided by Ulmo; from a cliff, Tuor became the first Man in Middle-earth to see the sea.[5]

Ossiriand

Ossiriand ("Land of Seven Rivers") was the most easterly region of Beleriand during the First Age, between the Ered Luin and the river Gelion. The Seven Rivers were the Gelion which ran from north to south, and its six tributaries flowing from the Ered Luin, named (from north to south) the Ascar, the Thalos, the Legolin, the Brilthor, the Duilwen, and Adurant. Ossiriand was a green and forested land. It was the only part of Beleriand that survived the War of Wrath, becoming known as Lindon, where Gil-galad and Círdan ruled.

Dor Daedeloth

Dor Daedeloth ("Land of the Shadow of Dread") far to the north, lay around the fortress of Angband and the Ered Engrin. It was here that the Orcs and other creatures of Morgoth lived and bred. The march of the Noldor early in the First Age was halted there, when Fëanor was mortally wounded by Balrogs. The Noldor then encircled the land, starting the Siege of Angband.

Concept and creation

Beleriand had many different names in Tolkien's early writings, including Broceliand, a name borrowed from medieval romance,[6] Golodhinand, Noldórinan ("valley of the Noldor"), Geleriand, Bladorinand, Belaurien, Arsiriand, Lassiriand, and Ossiriand (later used as a name for the easternmost part of Beleriand).[T 11]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- ^ Tolkien 1986, pp. 219-234. The overall geography of Beleriand will remain nearly unchanged from this map although many smaller details are added or subtracted as stories are developed, or rewritten.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, "Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Index of Names", "Arvernien"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Index of Names", "Doriath"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Index of Names", "Gondolin"

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Ch. 14 Of Beleriand and its Realms, ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The War of the Jewels, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, The Grey Annals, p. 77, ISBN 0-395-71041-3

- ^ See The Treason of Isengard, p. 124 and note 18, and Unfinished Tales, note on map in Introduction.

- ^ Tolkien 1986, "Commentary on Canto I"

Secondary

- ^ The New York Times Book Review, The Silmarillion, The World of Tolkien by John Gardner, 23 October 1977

- ^ The New York Times Book Review, The Book of Lost Tales, Language and Prehistory of the Elves By Barbara Tritel, 24 May 1984

- ^ The Guardian, Book Review, John Crace, The Children of Húrin by JRR Tolkien, 4 April 2007.

- ^ a b Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). The Lost Straight Road: HarperCollins. pp. 324–328. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Garth, John (2020). Tolkien's worlds : the places that inspired the writer's imagination. London: White Lion Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5. OCLC 1181910875.

- ^ a b Fimi, Dimitra (2007). "Tolkien's 'Celtic type of legends': Merging Traditions". Tolkien Studies. 4: 53–72. doi:10.1353/tks.2007.0015. S2CID 170176739.

Bibliography

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Shaping of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-42501-5

External links

- Parma Endorion: Essays on Middle-earth (3rd edition) by Michael Martinez

- Maps Of Middle-earth at www.douglas.eckhart.btinternet.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment