- Full Index to All Things Tolkien incld Rings of Power

- Tolkien - The History and Ages of Arda

- Cosmology of Tolkien's Legendarium

- Tolkien - The Ainur and Maiar of Middle-earth

- Tolkien - The Elves of Middle-earth and Valar of Vala

- The Inspiration of William Morris upon JRR Tolkien's Middle-Earth

- Tolkien's Tropes and Listings

- Tolkien - LOTR: The Rings of Power

- Middle-Earth: The Fall of Gondolin

- Middle-Earth: Beren and Luthien

- Middle-Earth: The Age of Numenor

- Middle-Earth: It's History, Unfinished Tales, Tom Bombadil, & the Lands of Beleriand

- Middle-Earth: The Many Worlds of the Silmarillion

- Middle-Earth: Sorting Out Tolkien's Many Titles & Works

- Middle-Earth: Lore, Legends, Symbols & Maps

- Middle-Earth: JRR Tolkien's Biography

- Middle-Earth: JRR Tolkien's Titles

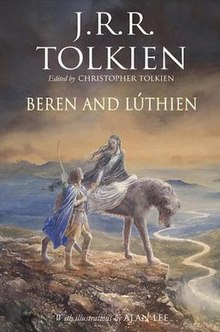

Beren and Lúthien

Front cover of the 2017 hardback edition | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Illustrator | Alan Lee |

| Cover artist | Alan Lee |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| Published | 2017[1] |

| Publisher | HarperCollins Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 297[note 1] |

| ISBN | 978-0-00-821419-7 |

| Preceded by | The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun |

| Followed by | The Fall of Gondolin |

Beren and Lúthien is a compilation of multiple versions of the epic fantasy Lúthien and Beren by J. R. R. Tolkien, one of Tolkien's earliest tales of Middle-earth. It is edited by Christopher Tolkien. It is the story of the love and adventures of the mortal Man Beren and the immortal Elf-maiden Lúthien. Tolkien wrote several versions of their story, the latest in The Silmarillion, and the tale is also mentioned in The Lord of the Rings. The story takes place during the First Age of Middle-earth, about 6,500 years before the events of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Beren, son of Barahir, cut a Silmaril from Morgoth's crown as the bride price for Lúthien, daughter of the Elf-king Thingol and Melian the Maia. He was slain by Carcharoth, the wolf of Angband, but alone of mortal Men returned from the dead. He lived then with Lúthien on Tol Galen in Ossiriand, and fought the Dwarves at Sarn Athrad. He was the great-grandfather of Elrond and Elros, and thus the ancestor of the Númenórean kings. After the fulfilment of the quest of the Silmaril and Beren's death, Lúthien chose to become mortal and to share Beren's fate.[T 1]

Tolkien found the inspiration for many of the ideas presented in the tale in his love for his wife (Edith) and after her death had "Lúthien" engraved on her tombstone, and later "Beren" on his own.

Development and versions

The first version of the story is The Tale of Tinúviel, written in 1917 and published in The Book of Lost Tales. During the 1920s Tolkien started to reshape the tale into an epic poem, The Lay of Leithian. He never finished it, leaving three of seventeen planned cantos unwritten. After his death it was published in The Lays of Beleriand. The latest version of the tale is told in prose form in one chapter of The Silmarillion and is recounted by Aragorn in The Fellowship of the Ring. Some early versions of the story, published in the standalone book in 2017, described Beren as a Noldorin Elf as opposed to a Man.[T 2]

Publication

The book was edited by Christopher Tolkien.[1][2][3][4] The story is one of three within The Silmarillion that Tolkien believed warranted their own long-form narratives, the other two being The Children of Húrin and The Fall of Gondolin. The book is illustrated by Alan Lee and edited by Christopher Tolkien, and it features different versions of the story, showing the development of the tale over time. It is restored from Tolkien's manuscripts and presented for the first time as a single more or less continuous narrative, using the ever-evolving materials that make up "The Tale of Beren and Lúthien". It does not contain every version or edit to the story, but those Christopher Tolkien believed would offer the most clarity and minimal explanation:

Approach

The book starts with the most complete version of the beginning of the tale, "The Tale of Tinúviel" as told in The Book of Lost Tales (with only slight editing of character and place names to avoid confusion with later versions). The general aspect of the story has not been modified; Beren, for example, is a Gnome (Noldo), the son of Egnor bo-Rimion, rather than the human son of Barahir. (Beren's heritage switches between elf and man throughout the book, depending on which portion of the story is being told.)

As Christopher Tolkien explains:

Further chapters continue the story in through later poems, summaries, and prose, showing how the story evolved over time, in order of the chronology of the story itself (not necessarily the order in which the texts were written or published). These include portions of various versions of "The Lay of Leithian", The Silmarillion, and later chapters of Lost Tales.

Since J. R. R. Tolkien made many changes to the story, affecting both narrative and style, the presentation in the book is not entirely consistent. There is some overlap of details and discrepancy in continuity, but the sections attempt a complete and continuous story. Christopher Tolkien included editorial explanations and historical details to bridge between sections. Details lost in later accounts were reintroduced: such as Tevildo (who due to the nature of his introduction is treated as a separate character, rather than an early conception of Sauron), Thû the Necromancer (treated as the first appearance of Sauron), the Wicked (or "treacherous") Dwarves (one of The Hobbit's references to Lost Tales), and other terminology such as Gnome (Noldoli, later Noldorin Elf), Fay, Fairy, leprechaun, and pixie. Some of these terms appear in early editions of The Hobbit, but were dropped in later writing.

The book offers an "in-universe" perspective for the inconsistencies, as owing to the evolution of the stories told by different perspectives and voices over time, rather than simply reflecting Tolkien's changing ideas over time.

- the First Age in The History of Middle-earth was in those books conceived as a history in two senses. It was indeed a history—a chronicle of lives and events in Middle-earth; but it was also a history of the changing literary conceptions in the passing years; and therefore the story of Beren and Lúthien is spread over many years and several books. Moreover, since that story became entangled with the slowly evolving Silmarillion, and ultimately an essential part of it, its developments are recorded in successive manuscripts primarily concerned with the whole history of the Elder Days.[T 6]

This book reintroduces details that were omitted in the highly edited version of The Silmarillion's "Of the Ruin of Doriath"; it includes the cursed treasure of Mîm, and the fact that Doriath was betrayed from the inside, and that Thingol was able to push the dwarves out of the city, and that he was later killed by an ambush of dwarves. It roughly reconciles the elements of early Lost Tales with details constructed by Guy Kay for the chapter in the Silmarillion, to bring it closer to J.R.R. Tolkien's intention (see The War of the Jewels).

- ...there are brought to light passages of close description or dramatic immediacy that are lost in the summary, condensed manner characteristic of so much Silmarillion narrative writing; there are even to be discovered elements in the story that were later altogether lost. Thus, for example, the cross-examination of Beren and Felagund and their companions, disguised as Orcs, by Thû the Necromancer (the first appearance of Sauron), or the entry into the story of the appalling Tevildo, Prince of Cats, who clearly deserves to be remembered, short as was his literary life.[T 7]

Reception

The Tolkien scholar John Garth, writing in the New Statesman, notes that it took a century for the tale of Beren and Lúthien, mirroring the tale of Second Lieutenant Tolkien watching Edith dancing in a woodland glade far from the "animal horror" of the trenches, to reach publication. Garth finds "much to relish", as the tale changes through "several gears" until finally it "attains a mythic power". Beren's enemy changes from a cat-demon to the "Necromancer" and eventually to Sauron. Garth comments that if this was supposed to be the lost ancestor of the Rapunzel fairytale, then it definitely portrays a modern "female-centred fairy-tale revisioning" with a Lúthien who may be fairer than mortal tongue can tell, but is also more resourceful than her lover.[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ 9 full-color illustrations

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ J. R. R. Tolkien (Christopher Tolkien, ed.), The Silmarillion, HarperCollins, London, 1999.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Book of Lost Tales, vol. 2, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ch. 1 "The Tale of Tinúviel": "Now Beren was a Gnome, son of Egnor the forester", ISBN 0-395-36614-3

- ^ Comments by Christopher Tolkien, in Tolkien, J.R.R. Beren and Lúthien (Kindle Locations 86-88). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Comments by Christopher Tolkien, in Tolkien, J.R.R. Beren and Lúthien (Kindle Locations 129-135). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Comments by Christopher Tolkien, in Tolkien, J.R.R. Beren and Lúthien (Kindle Locations 124-129). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Comments by Christopher Tolkien, in Tolkien, J.R.R. Beren and Lúthien (Kindle Locations 74-79). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Comments by Christopher Tolkien, in Tolkien, J.R.R. Beren and Lúthien (Kindle Locations 95-99). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

Secondary

- ^ a b "JRR Tolkien book Beren and Lúthien published after 100 years". BBC News. Oxford. 1 June 2017.

- ^ Flood, Alison (19 October 2016). "JRR Tolkien's Middle-earth love story to be published next year". The Guardian.

- ^ Helen, Daniel (17 February 2017). "Beren and Lúthien publication delayed".

- ^ "Beren and Lúthien on the Official Tolkien Online Book Shop". Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Garth, John (27 May 2017). "Beren and Lúthien: Love, war and Tolkien's lost tales". New Statesman. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

External links

Lúthien and Beren

| Lúthien | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Tinúviel |

| Race | Maia / Elf |

| Gender | Female |

| Book(s) | The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien |

| Beren | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Erchamion |

| Race | Human (Edain) |

| Gender | Male |

| Book(s) | The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien |

Lúthien and Beren are characters in the fantasy-world Middle-earth, narrated by the English author J. R. R. Tolkien. Lúthien is an elf, daughter of Thingol and Melian. Beren is a mortal man. The complex tale of their love for each other and the quest they are forced to embark upon, triumphing against overwhelming odds but ending in tragedy, appears in The Silmarillion, the epic poem The Lay of Leithian, the Grey Annals section of The War of the Jewels, and in other legendarium texts conflated into the 2017 book Beren and Lúthien, where it plays a central part. Their story is told to Frodo by Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings.

The story of Lúthien and Beren, immortal elf-maiden marrying a mortal man and choosing mortality for herself, is mirrored in Tolkien's The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen. The names Beren and Lúthien appear on the grave of Tolkien and his wife Edith.

Context

Lúthien was a Telerin (Sindarin) princess, the only child of Elu Thingol, king of Doriath, and his queen, Melian the Maia, making her half-royal, half-divine. She was born in the Years of the Trees, according to the Grey Annals. At her birth, the white flower niphredil bloomed for the first time in Doriath. Lúthien's romance with the mortal man Beren is considered the "chief" of the Silmarillion tales by Tolkien himself; he called it "the kernel of the mythology".[T 1] Elrond was Lúthien's great-grandson and Aragorn was descended from her via Elros and the Royal Family of Númenor. She is described as the Morning Star of the Elves and as the most beautiful daughter of the one god, Ilúvatar. Beren was the son of Emeldir and Barahir, a Man of the royal House of Bëor of Dorthonion.[T 2]

In contrast, Lúthien's descendant Arwen was called Evenstar, the Evening Star of the Elves, meaning that her beauty reflects that of Lúthien Tinúviel. Lúthien was first cousin once removed of Galadriel, whose mother, Eärwen of Alqualondë, was the daughter of Thingol's brother. The story of Lúthien and Beren is mirrored in The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen.[T 3][1]

Etymology

The name Lúthien appears to mean "daughter of flowers" in a Beleriandic dialect of Sindarin, but it can also be translated "blossom".[2] Tinúviel was a name given to her by Beren. It literally means "daughter of the starry twilight", which signifies "nightingale". The name Beren means "brave" in Sindarin.[T 4]

Fictional biography

Meeting

Beren saw Lúthien dancing under moonrise in her father's forest, and fell in love with her, for she was the most beautiful of Elves and Men. He stood in the shadows wishing to be near enough to Lúthien to touch her, but Daeron, her childhood friend and partner in music and dance, noticed Beren and, believing him to be a wild animal, shouted for Lúthien to flee. She saw Beren's shadow and ran away. But as she hid in the foliage, Beren touched her arm. Lúthien ran away in shock, believing it to be an animal stalking her in the woods. One day in summer when Lúthien was dancing on a green hill surrounded by hemlocks,[3] she sang, awakening Beren from his enchantment. He ran to her, and again she tried to escape and he cried Tinúviel ("nightingale"). When Lúthien gazed upon him for the first time she reciprocated his love. He kissed her on the lips, but she slipped away and he fell into a deep sleep. In his hour of despair, she appeared before him, and in the Hidden Kingdom set her hand in his and cradled his head against her breast. From then on they met secretly.[T 2]

The quest of the Silmaril

However, Daeron, who also loved her, reported her meetings with Beren to her father. Though Melian warned her husband against it, Thingol was determined not to let Beren marry his daughter, and set a seemingly impossible task as the bride price: Beren had to bring him one of the Silmarils from Morgoth's Iron Crown. Thingol did not kill Beren outright as he had promised Lúthien that he would spare Beren's life.[T 2]

Vision and imprisonment

Lúthien had a vision of Beren lying suffering in the hellish pits of the Lord of Wolves, and horror weighed upon her heart. She sought the counsel of her mother who told her that Beren was captive in the dungeons of Sauron, the Dark Lord's evil lieutenant. Lúthien decided to save Beren. She asked Daeron for help, but he betrayed her to Thingol. Thingol then had her guarded in the high branches of a great beech tree. Daeron was filled with remorse for his actions, and Lúthien forgave him, and devised a plan to escape. Using her magical power, Lúthien enchanted her hair into a cloak to lull her guards to sleep, and ran from her prison.[T 2]

On her way to rescue Beren, she found Huan, the Hound of Valinor, and was taken to his master Celegorm. He, plotting to force her to marry him, offered to help her, asking her to follow him to Nargothrond. When she arrived, Celegorm held her hostage and forbade her to talk to anyone else. Huan took pity on her, betraying his master, and freed her. Huan was granted the power to speak, and together they escaped from Nargothrond.[T 2]

They came to Sauron's Isle, and Lúthien sang a call to Beren. He answered, thinking it his imagination. Sauron, also hearing her song, sought to catch her and sent wolf after wolf to slay Huan, but Huan killed them, one by one. Finally, Sauron transformed himself into the most powerful of all werewolves and went out. Huan flinched, but Lúthien smothered Sauron's lunge in the folds of her enchanted cloak. Sauron changed into different shapes, but Huan bested him. Lúthien forced the defeated Sauron to surrender the keys of his tower; he fled in the shape of a vampire.[T 2]

Lúthien destroyed the Tower and freed its prisoners. Finding Beren, she thought him dead and fell down beside him in grief, but with the rising sun he awoke and they were reunited. Huan then returned to Celegorm.[T 2]

Celegorm, Curufin and the dance of Lúthien before Morgoth

Beren pleaded with Lúthien to return to her father, but she refused. As they were about to embrace, Celegorm and Curufin appeared, exiled because of Lúthien's escape from Nargothrond. Seeking revenge, they fought Beren, and Huan again fought on Lúthien's side. Beren defeated them, but spared their lives at Lúthien's request. Beren stole one of their horses, and the couple fled. As she slept he went to Angband to get the Silmaril.[T 2]

When Lúthien discovered Beren had left, she and Huan disguised themselves as Thuringwethil, the vampire servant of Morgoth, and Draugluin the Werewolf. She found Beren and joined his quest. Together Beren and Luthien reached the Throne of Morgoth, but the Dark Lord saw through Lúthien's disguise. She declared herself and offered to sing for Morgoth. Filled with an evil lust, he accepted, thinking to toy with her, but she put him and his entire court into a deep sleep. She awakened Beren, and he cut a Silmaril from Morgoth's crown. However, as he tried for another Silmaril, his blade snapped, striking Morgoth's cheek. Lúthien and Beren fled to the gates, where Carcharoth, the greatest of Morgoth's werewolves and the guardian of the gates, attacked them. Beren thrust the Silmaril into the wolf's face, but the wolf bit off Beren's hand and swallowed it and the Silmaril. With the hosts of Angband roused, Lúthien sucked out the venom, and with her failing power tried to restore Beren. Just when all hope seemed lost, the Eagles of Manwë came at the summons of Huan and carried them to Doriath.[T 2]

Return to Doriath and death of Beren

Lúthien waited by Beren's side and healed him. Then together they entered and stood before the throne of Lúthien's father. Beren told Thingol that the quest was, indeed, fulfilled, and that he held a Silmaril in his hand. When Thingol demanded to see it, Beren showed him his stump. The couple then explained what had happened. They were married before Thingol's throne that day. Meanwhile, Carcharoth slaughtered all the living beings he came across in his frenzied flight, both empowered and tormented by the jewel burning his stomach. Beren, Thingol, Huan, and other Elves went to defeat the beast. Beren was attacked by the wolf; Huan leaped to his aid and killed the beast, but died soon afterwards of his wounds. Beren was carried to Doriath, where he died in Lúthien's arms.[T 2]

Lúthien becomes mortal for Beren

In grief, Lúthien lay down and died, going to the Halls of Mandos, Lord of the Dead.[a] There she sang a song of the tribulations and suffering of both Elves and Men woe before the throne of Mandos, the greatest ever sung. It was so touching that Mandos was moved to pity for the only time. He summoned Beren from the houses of the dead, and Lúthien's spirit met his by the shores of the sea. Mandos consulted with Manwë, King of Arda. Even Manwë could not change the fate of Men, and so he gave Lúthien two choices: to live in the immortal land of Valinor, where she could forget all her grief and enjoy eternal happiness along with her people and the Valar, but without Beren; or to return to Middle-earth with Beren as a mortal herself, accepting the Doom of Men. She chose mortality, relinquishing everything for Beren.[T 2]

Return to life, and death

Lúthien and Beren dwelt together in Ossiriand until after the sack of Menegroth. Their abode was known as Dor Firn-i-Guinar: the "Land of the Dead that Lived". They had a son, Dior, called Eluchíl — the heir of Thingol.[T 5]

Years later, Thingol received the Nauglamír from Húrin, who had recovered it from the ruins of Nargothrond after the departure of Glaurung the dragon. Thingol decided to unite the greatest works of the Dwarves and the Elves - the Nauglamír and the Silmaril - and hired Dwarf smiths from Nogrod for the task. Thingol was then murdered by the Dwarves, who plundered his treasuries and took the Nauglamír. Beren and an army of Green Elves and Ents waylaid the returning Dwarf army. Beren reclaimed the Nauglamír, and Lúthien kept the necklace and the great jewel all her life. This hastened Beren's and Lúthien's end, since her beauty enhanced by the jewel was too bright for mortal lands to bear.[T 6]

Elrond and Arwen were descendants of Lúthien, as was Aragorn, a descendant of Elrond's brother Elros.[T 3]

Earlier versions

In the various versions of The Tale of Tinúviel, Tolkien's earliest form of his tale, as published in The Book of Lost Tales, her original name is Tinúviel (Lúthien was invented later). Beren is, in this earlier version, an Elf (specifically a Noldo, or Gnome), and Sauron has not yet emerged. In his place, they face Tevildo, the Prince of Cats, a monstrous cat who is the principal enemy of the Valinorean hound Huan. However Tolkien initially created the character of Beren as a mortal man before this in an even earlier but erased version of the tale.[T 7]

The story is also told in an epic poem in The Lays of Beleriand, upon which most of the finer details of her life and relationship to Beren is extracted from in this article, since The Silmarillion provides only a generalization of the tale.[T 8]

Inspirations

In a letter to his son Christopher, dated 11 July 1972, Tolkien requested the inscription below for his wife Edith's grave "for she was (and knew she was) my Lúthien."[T 9] He added, "I never called Edith Luthien – but she was the source of the story.... It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks at Roos in Yorkshire where ... she was able to live with me for a while."[T 9] In a footnote to this letter, Tolkien added "she knew the earliest form of the legend...also the poem eventually printed as Aragorn's song."[T 9] Particularly affecting for Tolkien was Edith's conversion to the Catholic Church from the Church of England for his sake upon their marriage; this was a difficult decision for her that caused her much hardship, paralleling the difficulties and suffering of Lúthien from choosing mortality.[4]

The Tale of Beren and Lúthien also shares an element with folktales such as the Welsh Culhwch and Olwen and others — namely, the disapproving parent who sets a seemingly impossible task (or tasks) for the suitor, which is then fulfilled.[5]

The Tolkien grave

Edith and J. R. R. Tolkien lie in Wolvercote Cemetery in north Oxford. Their gravestone shows the association of Lúthien with Edith, and Tolkien with Beren.[6] The stone reads:

Notes

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Letters, #165 to the Houghton Mifflin Co., 30 June 1955

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tolkien 1977, ch. 19 "Of Beren and Lúthien"

- ^ a b The Return of the King, Appendix A: The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen

- ^ Christopher Tolkien (1989), The History of Middle-earth, The Lost Road, p.352; ISBN 0-395-45519-7

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 20 "Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 22 "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- ^ Tolkien 1984, book 2, ch. 1 "The Tale of Tinúviel"

- ^ Tolkien 1985, part 3, ch. 1 "The Gest of Beren son of Barahir and Lúthien the Fay called Tinúviel the Nightingale or the Lay of Leithian – Release from Bondage"

- ^ a b c Letters, #340 to Christopher Tolkien, 11 July 1972

Secondary

- ^ Bowman, Mary R. (October 2006). "The Story Was Already Written: Narrative Theory in "The Lord of the Rings"". Narrative. 14 (3): 272–293. doi:10.1353/nar.2006.0010. JSTOR 20107391. S2CID 162244172.

- ^ Noel, Ruth S. "The Languages of Tolkien's Middle-earth", page 166. Houghton Mifflin, 1974

- ^ "Beren and Lúthien and the hemlock glade". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on November 29, 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 73.

- ^ Hnutu-healh, Glyn (6 January 2020). "Culhwch and Olwen". Arthurian Legends. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Birzer, Bradley J. (13 May 2014). J. R. R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth. Open Road Media. p. pt35. ISBN 978-1-4976-4891-3.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977), J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Book of Lost Tales, vol. 1, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-35439-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lays of Beleriand, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-39429-5

External links

- LaSala, Jeff (September 14, 2016). "Lúthien: Tolkien's Badass Elf Princess". Tor.com. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment