As both a Progressive Christian and Process-based Christian this website here does stand on the side of equal civil rights for all regardless of sex, gender, race, culture, religion, or nationality. Either we are at the beginning of a better democracy than America has ever known before as its pluralistic culture unites itself with the United States Constitution to observe liberty and equality for all its peoples. Or, we are at the very end of Jeffersonian democracy as it shatters under the weight of white Christian nationalists, white supremacists, and social media propagandists seeking to remake America into their own monolithic image of intolerance for all, to all, and by all. Thus today's belated survey bookending the civil rights protests begun in the 1950s and 60s seventy years earlier....

R.E. Slater

October 28, 2021

* * * * * * * * *

Dramatic Partisan Differences On Blame

for January 6 Riots

09.15.2021

Majorities of Americans Place Blame for January 6 Insurrection on White Supremacist Groups, Donald Trump, and Conservative Media Platforms, But Dramatic Partisan Differences Persist.

According to new data from PRRI, majorities of Americans say white supremacist groups (59%), former president Donald Trump (56%), and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (55%) shoulder a lot of responsibility for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the U.S. Capitol on January 6. These views have stayed remarkably stable since mid-January, when 62% placed a lot of blame on white supremacist groups, 57% on Trump, and 57% on conservative media platforms that spread misinformation. There are not significant differences between these numbers and January data within subgroups, either.

Additionally, about four in ten Americans put a lot of the blame for the Capitol riot on Republican leaders (41%), and 29% put a lot of the blame on white conservative Christian groups. Despite the lack of any credible evidence that substantial numbers of liberal or left-wing groups participated in the riot, 38% put a lot of blame on these groups.

Blame Attribution by Party Affiliation

Republicans assign blame for the Capitol riots very differently from most Americans. About three in ten Republicans hold white supremacist groups (30%) and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (27%) responsible for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Only 15% of Republicans place a lot of blame on Donald Trump, and less than one in ten say Republican leaders (9%) and white conservative Christian groups (8%) hold a lot of responsibility for the Capitol riots. Strikingly, six in ten (61%) Republicans place a lot of responsibility for the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol on liberal or left-wing activists. Liberal activists are the only group a majority of Republicans say bear a lot of responsibility for this event.

Republicans’ blame attributions vary by which media sources they trust most to provide accurate information about politics and current events. Only a sliver of Republicans who most trust Fox News and far-right sources such as Newsmax and One America News Network say Trump holds a lot of the blame (3% each), and similarly few place a lot of blame on white conservative Christian groups (2% and 1%, respectively) and Republican leaders (2% and 0%, respectively). Fox News viewers are more likely than far-right news viewers to say a lot of blame goes to white supremacist groups (25% and 17%, respectively) and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (21% and 15%, respectively). Not surprisingly, far-right news viewers are more likely than Fox News viewers to falsely assert that a lot of blame goes to liberal or left-wing activists for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol (76% and 69%, respectively), though both groups overwhelmingly hold this view.

By contrast, Republicans who most trust broadcast network news, such as NBC, ABC, and CBS, are much more likely to place a lot of blame with white supremacist groups (61%), Donald Trump (50%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (46%), Republican leaders (23%), and white conservative Christian groups (21%). Still, a majority (53%) also assign a lot of blame to liberal and left-wing activists.

The vast majority of Democrats assign a lot of responsibility for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6 to Donald Trump (89%), white supremacist groups (83%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (78%), and Republican leaders (70%). About half of Democrats say white conservative Christian groups (48%) hold a lot of blame, and nearly three in ten (27%) hold liberal or left-wing activists responsible.

Independents fall in between Republicans and Democrats, with majorities saying white supremacist groups (59%), Donald Trump (57%), and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (55%) hold a lot of the blame for January 6. Fewer place a lot of the blame on Republicans leaders (37%), liberal or left-wing activists (34%), and white conservative Christian groups (27%).

Blame Attribution by Religion

White Christian groups are much less likely to blame right-leaning people or groups than other religious groups. White evangelical Protestants’ attitudes closely resemble those of Republicans in that few place a lot of blame for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6 on Donald Trump (26%), Republican leaders (16%), and white Christian conservative groups (8%). More than one-third say white supremacist groups (37%) and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (34%) hold a lot of the blame. The only group a majority of white evangelical Protestants blame for the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol is liberal or left-wing activists (57%).

Nearly half of white mainline (non-evangelical) Protestants put a lot of blame on white supremacist groups (49%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (45%), liberal or left-wing activists (44%), and Donald Trump (43%). A majority of white Catholics place a lot of blame with white supremacist groups (54%) and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (54%), while half (50%) attribute a lot of blame to Trump and 44% say liberal or left-wing activists hold a lot of the blame for the violent attack.

By contrast, eight in ten Black Protestants (80%) say white supremacist groups hold a lot of the blame, as do 73% of Hispanic Catholics, 69% of Jewish Americans, 65% of religiously unaffiliated Americans, 65% of other Protestants of color, 63% of other Christians, 62% of other non-Christian religious Americans, 59% of Hispanic Protestants, and 56% of Latter-day Saints. Similarly, about two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated Americans (67%), Black Protestants (66%), and other Christians (65%) place a lot of blame on conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation, as do 59% of Hispanic Catholics, 58% of other Protestants of color, 55% of Jewish Americans, and 51% of Latter-day Saints. Less than half of Hispanic Protestants (48%) say the same.

Black Protestants are most likely to put a lot of the blame on Trump (79%), as are majorities of other Christians (74%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (69%), Hispanic Catholics (69%), other Protestants of color (65%), Hispanic Protestants (64%), other non-Christian religious Americans (64%), and Jewish Americans (57%). Less than half of Latter-day Saints (48%) say Trump shoulders a lot of the blame.

Blame Attribution by Views of Trump

Trump Favorability

Donald Trump’s favorability ratings remain about the same as they were in January: 34% of Americans hold favorable views of the former president, while 64% hold unfavorable views of him, including a 51% majority of Americans who hold very unfavorable views of him. In January, 31% of Americans viewed Trump favorably and 67% unfavorably, with 54% who viewed him very unfavorably.

Not surprisingly, only 8% of those who view Trump favorably blame him a lot for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, compared to 83% of those who view him unfavorably.

About one in four Americans who view Trump favorably blame white supremacist groups (27%) and conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (24%) a lot for the violence on January 6, and fewer assign a lot of blame to Republican leaders (7%) and white conservative Christian groups (7%). Among Americans who view Trump favorably, six in ten (60%) assign a lot of responsibility for the attack on the U.S. Capitol to liberal or left-wing activists.

By contrast, majorities of Americans who view Trump unfavorably assign a lot of responsibility to white supremacist groups (77%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (73%), and Republican leaders (60%). They are less likely to blame white conservative Christian groups (42%) and liberal or left-wing activists (27%).

Belief That Trump Is a “True Patriot”

About one-third of Americans agree that “President Trump is a true patriot” (34%), compared to 63% who disagree, including nearly half (49%) who completely disagree. These views have not changed since January 2021. Not surprisingly, Republicans (79%) are substantially more likely to think that Trump is a true patriot than independents (34%) and Democrats (7%).

Views of Trump as a true patriot are highly correlated with low blame attribution for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Among those who view Trump as a true patriot, only 10% blame him for the attack on the Capitol, compared to 83% of those who disagree that Trump is a true patriot.

White evangelical Protestants are the only religious group among whom a majority agree that Trump is a true patriot (68%). The only other religious groups among whom more than four in ten agree are white mainline Protestants (45%) and white Catholics (45%). Strong majorities of all other religious groups reject this idea.

Few Americans who think Trump is a true patriot place a lot of blame for January 6 on white supremacist groups (27%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (25%), white conservative Christian groups (8%), or Republican leaders (7%). Most Americans who view Trump as a true patriot assign a lot of responsibility for the attack on the U.S. Capitol to liberal or left-wing activists (59%).

By contrast, majorities of Americans who disagree that Trump is a true patriot assign a lot of responsibility to white supremacist groups (77%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (72%), and Republican leaders (60%). They are less likely to blame white conservative Christian groups (41%) and liberal or left-wing activists (27%) for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the U.S. Capitol building on January 6.

Blame Attribution by the Belief That the 2020 Election

Was Stolen From Donald Trump

Less than three in ten Americans (29%) agree that “The 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump,” compared to 69% who disagree, including 58% who completely disagree. These views have remained stable since March 2021. But Republicans hold views that are far outliers compared to the opinions of other Americans. More than seven in ten Republicans (71%) report that they believe the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, compared to 23% of independents and only 5% of Democrats.

The only religious group among whom a majority believes the election was stolen are white evangelical Protestants (61%). About four in ten white mainline Protestants (40%) and white Catholics (39%) agree, but less than one in three of every other religious group say the election was stolen.

Not surprisingly, given the goal of the January 6 rioters was to keep Trump in the White House, only 7% of Americans who agree that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump blame him a lot for the violence that took place that day, compared to 78% among those who disagree that the 2020 election was stolen from him.

Among those who agree that the election was stolen from Trump, few blame white supremacist groups (24%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (23%), white conservative Christian groups (7%), or Republican leaders (7%). Most Americans who agree that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump place a lot of blame on liberal or left-wing activists (63%) for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the Capitol.

By contrast, majorities of Americans who disagree that the election was stolen from Donald Trump assign a lot of responsibility to white supremacist groups (74%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (70%), and Republican leaders (56%). They are less likely to blame white conservative Christian groups (39%) and liberal or left-wing activists (28%) for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the U.S. Capitol building on January 6.

Blame Attribution by QAnon Beliefs

Many believers of QAnon conspiracy theories participated in the Capitol siege that disrupted the certification of President Joe Biden’s election victory.

In this analysis, QAnon beliefs are measured based on respondents’ feelings about three statements: (1) The government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation; (2) There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders; and (3) Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country. QAnon believers (17% of Americans) mostly agree with these statements, whereas doubters (48% of Americans) are generally negative toward them and rejecters (35% of Americans) strongly disagree with all three statements.

[1]

Belief in QAnon conspiracies is correlated with blame attribution for the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Only about one-third or less of QAnon believers assign a lot of responsibility for the January 6 attack to white supremacist groups (36%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (36%), Donald Trump (30%), Republican leaders (23%), and white conservative Christian groups (18%). The only group the majority of QAnon believers hold responsible for the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6 is liberal or left-wing activists (59%).

By contrast, strong majorities of QAnon rejecters assign a lot of responsibility for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the Capitol to Donald Trump (83%), white supremacist groups (78%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (78%), and Republican leaders (61%). Only 20% of QAnon rejecters assign a lot of responsibility for the attacks on the Capitol building to liberal or left-wing activists.

Blame Attribution by Views of the Impact of Violent Rhetoric

Nine months after the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, opinions about how much harsh and violent language in politics contributes to violent actions in society remain stable. Nearly six in ten Americans (56%) say that harsh and violent language in politics contributes “a lot” to violent actions in society today, compared to 60% in January 2021. An additional 33% say it contributes a little, slightly up from 30% in January, and only 10% say harsh and violent political language does not contribute at all to violent action, virtually the same as in January (9%).

Democrats are significantly more likely than Republicans to say that harsh and violent language contributes a lot to violent actions (75% vs. 40%), views that have not shifted significantly since January (79% and 37%, respectively). A slightly smaller majority of independents (54%) think that violent language contributes a lot to violent action today than in January (61%).

Majorities of Americans who think that harsh and violent language contributes a lot to violent actions today assign a lot of responsibility to white supremacist groups (74%), Donald Trump (74%), conservative media platforms that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation (72%), and Republican leaders (57%) for the violent actions of the rioters who took over the Capitol. Fewer assign a lot of responsibility to white conservative Christian groups (41%) or liberal or left-wing activists (37%). By contrast, among Americans who think that harsh and violent language has no influence on violent actions today, one in five or less blame any of these groups, except for liberal or left-wing activists, for the events of January 2021.

The Chasm Between Our Political Parties Revealed by the January 6 Insurrection

As the above analysis indicates, not only on specific issues related to the January 6 insurrection but also on perceptions of the link between harsh rhetoric and violent actions, we see strong asymmetric partisan polarization. Increasingly, Republicans hold views on these issues that are outliers compared to the views of other Americans. In partisan terms, political independents hold views much closer to those of Democrats than Republicans.

The chart below shows the distance between partisans and independents on several of the attitudes measured in this report: assigning blame to Donald Trump for the violent January 6 attacks on the U.S. Capitol, belief that Trump is a true patriot, belief that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, belief in QAnon conspiracy theories, and beliefs in the links between harsh rhetoric and violent actions.

The gap between Democrats and Republicans on these measures is best described as a canyon. There is a 74-percentage-point difference in placing a lot of blame for violent attacks on the U.S. Capitol on January 6 on Donald Trump between Democrats (89%) and Republicans (15%). Similarly, the difference in thinking Trump is a true patriot is 72 percentage points between partisans (79% Republicans, 7% Democrats), and an astonishing 71% of Republicans think the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, compared to only 5% of Democrats. A smaller gap exists on how violent language affects violent actions, but the 35-percentage-point difference between Democrats (75%) and Republicans (40%) is still quite large. Perhaps most frightening, although the smallest gap in terms of percentage differences, nearly three times more Republicans (29%) than Democrats (9%) believe QAnon conspiracy theories. There seems to be little chance for cross-party agreement on issues involving Trump and the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6.

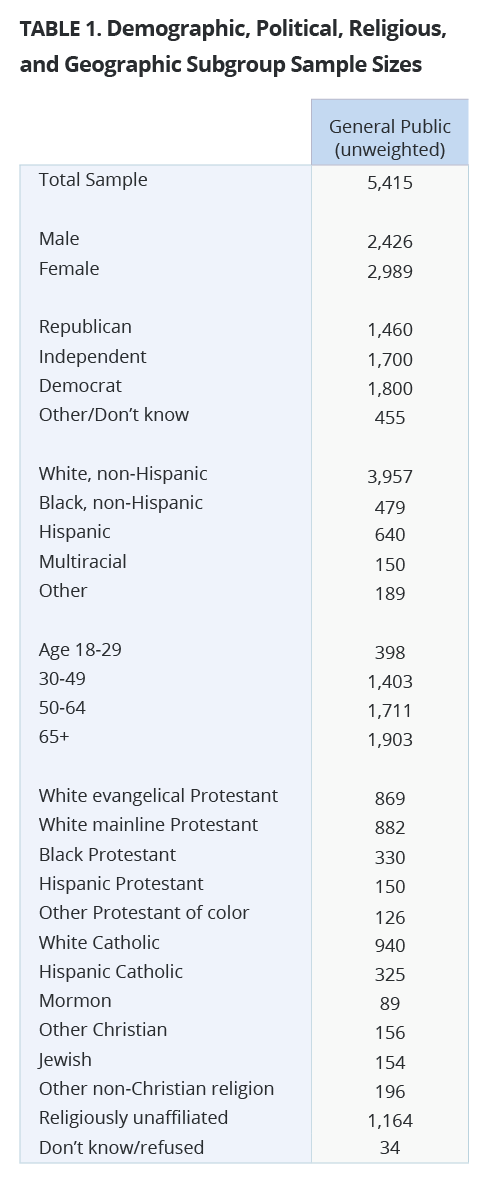

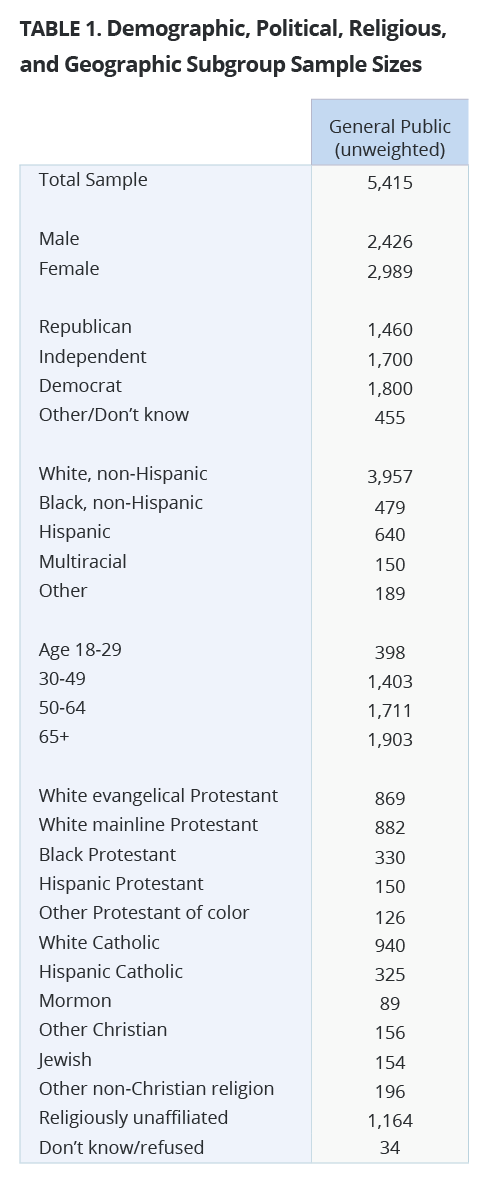

Survey Methodology

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI among a representative sample of 5,415 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States, including 5,032 who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 383 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Interviews were conducted online between August 9 and 30, 2021.

Respondents are recruited to the KnowledgePanel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS – a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

The initial sample drawn from the KnowledgePanel was adjusted using pre-stratification weights so that it approximates the adult U.S. population defined by the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey. Next, a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling scheme was used to select a representative sample.

To reduce the effects of any non-response bias, a post-stratification adjustment was applied based on demographic distributions from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS). The post-stratification weight rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, Census division, metro area, education, and income. The sample weighting was accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights were trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results. In addition to an overall national weight, separate weights were computed for each state to ensure that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. The state-level post-stratification weights rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, and income.

These weights from the KnowledgePanel cases were then used as the benchmarks for the additional opt-in sample in a process called “calibration.” This calibration process is used to correct for inherent biases associated with nonprobability opt-in panels. The calibration methodology aims to realign respondents from nonprobability samples with respect to a multidimensional set of measures to improve their representation.

The margin of error for the national survey is +/- 1.86 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence, including the design effect for the survey of 1.96. In addition to sampling error, surveys may also be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects. Additional details about the KnowledgePanel can be found on the Ipsos website:

https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solution/knowledgepanel

Endnotes

[1] For more on QAnon beliefs, see PRRI’s previous report:

Home Page Featured image: Tyler Merbler